Introduction

The class cleavage was pivotal in structuring political conflict in advanced democracies in the postwar era. However, in the 1980s and 1990s, scholars began questioning the enduring influence of class on vote choice (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Lipset and Rempel1993; Dalton, Reference Dalton1996; Franklin, Reference Franklin1985; Kelley and McAllister, Reference Kelley and McAllister1985). Many scholars have identified an increasing tendency by working-class voters to support right-wing parties (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Surridge2020; Hildebrandt and Jäckle, Reference Hildebrandt and Jäckle2021; Oskarson and Demker, Reference Oskarson and Demker2015; Stonecash, Reference Stonecash2017; Stubager, Reference Stubager2013; Zingher, Reference Zingher2020). Studies of the rightward movement of working-class electorates regularly come back to socio-cultural issues, such as immigration, as a key driver (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Houtman at al., Reference Houtman, Achterberg and Derks2009; Rennwald, Reference Rennwald2020), regardless of whether they operate as an economic (labour market competition) or cultural (loss of traditional definition of national identity) threat.

While much attention has been paid to the changing class cleavage in Western politics, overall class voting in Canada has been neglected, largely because of the belief that class voting was essentially absent, dominated instead by linguistic, regional and religious divisions (Alford, Reference Alford1963; Porter, Reference Porter1965). This was a fairly simplistic view, and more recent research has documented that class has been a weak, but not absent, cleavage in Canadian politics (Andersen, Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013).

However, a reassessment of this relationship is warranted for several reasons. First, scholarly interest in how social class shapes voting behaviour has waned recently. The most recent examination of class voting in Canada stopped at 2004, and there have been six federal elections since. Around this time, the party system underwent considerable transformation, as the two largest conservative parties merged into the Conservative Party in 2002. That party formed the national government from 2006 until 2015. The social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP) also adopted a more professional and modernized outlook under former leader Jack Layton (Laycock and Erickson, Reference Laycock and Erickson2014; McGrane, Reference McGrane2019). This occurred at the same time as electoral financing laws were enacted, which prohibited corporate and union donations to federal political parties. Thus, one of the primary conduits by which the NDP was shaped as a labour party was severely weakened (Jansen and Young, Reference Jansen and Young2009). However, at the same time, from 2004 until 2011, the NDP also experienced dramatic growth in support, winning its best result as official opposition in 2011 before falling back to historic levels in 2015 and 2019. Moreover, this all occurred against the backdrop of the 2008 global financial crisis, which increased concerns about inequality around the world and in Canada (Banting and Myles, Reference Banting and Myles2013; Hacker, Reference Hacker2019; Piketty, Reference Piketty2014). Last, the theoretical expectation that working-class voters will support social democratic parties has been challenged by studies of the erosion of that support in many Western countries, often on the basis of anti-immigration appeals (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Houtman et al., Reference Houtman, Achterberg and Derks2009; Rennwald, Reference Rennwald2020). Although working-class hostility to immigration has often been a source of working-class support for right-wing parties, the nativist cleavage is comparatively weak in Canada and support for immigration comparatively high (Banting and Soroka, Reference Banting and Soroka2020). Still, while supporters of the different parties long had similar levels of support for immigration, a gap has grown between Liberal and NDP supporters and Conservative supporters since 2004 (Banting and Soroka, Reference Banting and Soroka2021). Thus, examining class voting in Canada can improve our understanding of the contributions and limitations of these narratives.

This article updates Andersen's (Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013) analysis of the class-party relationships in Canada by including data for post-2004 elections and engages three questions: First, did the class-party relationship identified by Andersen persist despite changes in the NDP? Second, is there evidence in Canada of a shift in working-class voting away from the NDP and toward conservative parties? And third, what drives workers to support parties of the left or the right?

We develop four main conclusions. First, we find a weakened, but still discernible, class cleavage in Canada outside Quebec. Although workers still tended to prefer the Conservatives and Liberals, New Democratic voters still tend to come more from the working class, as opposed to other classes. Second, in contrast to Andersen's study from 1965 to 2004, we find that the NDP has added support among several classes other than the traditional working class, diluting the class-based nature of its electorate. Third, we find, starting in 2004, a clear trend whereby workers have tended to increase their support for the Conservative Party, primarily at the expense of the Liberals. The Conservative electorate of today is effectively a coalition of managers and workers. Fourth, when studying the drivers of this increased working-class conservatism, we find that moral traditionalism and anti-immigration stand out as increasingly significant correlates of support. We also find that there is increased partisan sorting between NDP and Conservative working-class voters on economic issues and that workers are also moved to support the NDP based on their views on redistribution.

Class Voting: Canada in Comparative Perspective

The study of class voting owed a great deal to Lipset's (Reference Lipset1959) characterization of the “democratic class struggle,” whereby the class cleavage opposing workers and owners, or those with lower incomes and those with higher incomes, is played out in the conflict between left-wing and right-wing parties. For Lipset (Reference Lipset1963: 234), “in virtually every economically developed country the lower-income groups vote mainly for parties of the left, while higher income groups vote mainly for parties of the right.” At the same time, Lipset was aware of the ways in which voters were cross-pressured:

The poorer everywhere are more liberal on such issues; they favor more welfare state measures, higher wages, graduated income taxes, support of trade-unions, and other measures opposed by those of higher class position. On the other hand, when liberalism is defined in non-economic terms—so as to support, for example, civil liberties for political dissidents, civil rights for ethnic and racial minorities, internationalist foreign policies and liberal immigration legislation—the correlation is reversed. (Lipset, Reference Lipset1959: 485)

From the beginning, the Canadian case sat uneasily with Lipset's framework. Famously, Alford (Reference Alford1963) described Canada as exhibiting “pure non-class” voting. But it was a pure non-class voting that was not built on the “cultural” issues Lipset had in mind. Instead, Canadian voting behaviour has been dominated by the strength of regional, religious and national cleavages. Lijphart (Reference Lijphart1979) underlined that when comparing what the literature considered as the three most important socio-demographic factors affecting party choice, religion was the strongest in the Canadian case, followed by language, with class a distant third. He suggested that the Canadian party system reflected the dominance of religious cleavages at founding to such an extent that even the linguistic conflicts that roiled Canadian politics in the 1970s were expressed more through intergovernmental relations than the party system. The majority of Canadian scholars arrived at similar conclusions. For instance, Anderson and Stephenson describe class voting as nearly non-existent (Reference Anderson and Stephenson2010: 17). The scholarship has emphasized that voters are “flexible partisans” with weak attachments to parties and a propensity to change their votes from one election to the next. In this context, class, as measured by income, is not a good predictor of party preference (Clarke and Kornberg, Reference Clarke and Kornberg1996).

Not all scholars are convinced that class is unimportant in Canadian voting behaviour. One stream of scholarship demonstrated that there was class voting but it was highly contingent. For example, Gidengil (Reference Gidengil1989) found evidence of class voting in Canada in the 1960s and 1970s that was heavily conditioned on the structural location of voters’ regions in the Canadian economy. Class voting emerged only in industrialized regions at the centre of the Canadian economy. In peripheral regions, working-class voters tended to support the Conservative Party. The patterns of regional dependency in Canada that produced such regionalized class voting also prevented the development of a class cleavage in voting at the national level (Gidengil, Reference Gidengil and Baer2002). More recently, using income to measure class, Kay and Perrella (Reference Kay, Perrella, Kanji, Bilodeau and Scotto2012: 132) found that the class effect is comparable to that of gender and age.Footnote 1

Above all, the most important contextual element facilitating class voting has been working-class membership in unions, many of which have been formally affiliated with the NDP. Archer (Reference Archer1990) found important contextual effects of union affiliation with the NDP, whereby respondents who were members of NDP-affiliated unions were much more likely to support the NDP than were members of non-NDP-affiliated unions. Butovsky's (Reference Butovsky2001: 112–14) study of the 1984 and 1997 elections likewise found that unionization better predicted class voting than did occupation, although its effect operated for men but not women. On this view, insofar as the NDP has had a class character, it is because of its relationship with unions (Johnston, Reference Johnston2017). Similarly, Brym et al. (Reference Brym, Gillespie and Lenton1989) found that rates of union and co-operative membership in provinces led to higher levels of support for the NDP by union members, suggesting that union members are better able to vote for their own party in situations where the union movement has more resources and visibility. Later, Nakhaie and Arnold (Reference Nakhaie and Arnold1996) found modest effects of objective class variables on voting for the NDP in 1984, but these worked entirely through ideology. They took a more sociological approach of assuming unions assisted in producing a self-conscious working class, although here again there was difficulty showing that union members’ voting reflected a working-class as opposed to middle-class identity (Pammett, Reference Pammett1987). Last, Andersen's Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013 study provides evidence for the role of the union movement in facilitating any kind of class voting. While working-class voters were most likely to vote Liberal or Conservative, membership in the working class was the strongest predictor of NDP support, but his analysis did not include union status.

While Canadian political scientists have turned away from investigating class, European and American scholars have demonstrated increasing interest. For example, Przeworksi and Sprague (Reference Przeworski and Sprague1986) documented the need to produce cross-class electoral coalitions, often with segments of new middle-class professionals such as public sector workers, because the manual working class never made up a majority of the electorate. The difficulty of sustaining these coalitions, considering divergent class concerns and attitudes, has been an enduring source of interest. This led to the scholarship of the 1990s on whether social class, class politics and class voting (each different) were declining, changing or fluctuating (Clark and Lipset, Reference Clark and Lipset1991; Evans Reference Evans1999; Manza and Brooks, Reference Manza and Brooks1999; Nieuwbeerta and de Graaf, Reference Nieuwbeerta, de Graaf and Evans1999).

Recent scholarship suggests that something substantial has changed in class politics. Many posit that the left-right conflict over economic and redistributive issues, which organized politics in most Western industrialized countries in the twentieth century, is no longer the dominant dimension of electoral politics. It has been joined by a libertarian-authoritarian dimension, which plays out in conflicts over issues such as immigration and traditional values (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart1977, Reference Inglehart1990). These dynamics are also evident in—and potentially facilitated by—changes in the choices that parties offer to voters. While much of the research on spatial models of competition revolve around party positioning in a unidimensional space where each party chases a median voter, the literature on the changing nature of class cleavages often emphasizes the multidimensional nature of political competition. Achterberg (Reference Achterberg2006) studied the relative emphasis on class, environmental and cultural issues in platforms in capitalist countries from 1945 to 1998 and found a striking increase in the salience of cultural issues. He also found that the increasing salience of cultural issues contributed to working-class voters supporting right-wing parties and to middle-class voters supporting left-wing parties. Similarly, Andersen's (Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013) analysis found an increase in “new politics” issues that coincided with a shift to the right between 1965 and 2000.

For Norris and Ingelhart (Reference Norris and Ingelhart2019), the increased salience of cultural issues has accompanied the “silent revolution” of growing support for postmaterial values through generational replacement. This has produced a “tipping point” where holders of socially conservative values see their formerly dominant position slipping away and mobilize an authoritarian backlash. This has a particular class relevance, as the working class is one of the groups where socially conservative values remain the strongest. As such, a politics increasingly defined by the libertarian-authoritarian dimension returns us to Lipset's cross-pressured working-class voter.

In this context, working-class voters are led to vote for the right, while upper-class voters are led to vote for the left, largely because of their low (or high, respectively) levels of cultural capital and education (Houtman at al., Reference Houtman, Achterberg and Derks2009). On the cultural dimension, these groups are strongly opposed, with working-class voters proving to be more authoritarian, particularly on issues of migration (Hildebrandt and Jäckle, Reference Hildebrandt and Jäckle2021: 10; Rennwald, Reference Rennwald2020). As social democratic parties have retreated from demands for redistribution due to the presumed imperatives of globalization, they have allowed right-wing parties to prime the electorate to issues of immigration (Beramendi et al., Reference Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015).

The net result is growing working-class voting for right-wing parties. For instance, concerns about unrestricted immigration were central to working-class support for Brexit, as well as for the Conservatives in the 2019 United Kingdom general election (Cutts et al., Reference Cutts, Goodwin, Heath and Surridge2020). This pattern of a working class deserting the left and moving to the right is repeated in many recent country case studies of class voting. Examples include Zingher (Reference Zingher2020) and Stonecash (Reference Stonecash2017) for the United States; Rennwald (Reference Rennwald2014) for Switzerland; Stubager (Reference Stubager2013) for Denmark; and Oskarson and Demker for Sweden (Reference Oskarson and Demker2015). An exception to this trend is Helgason's (Reference Helgason2018) study of Iceland, which finds that class voting has increased, albeit in the aftermath of the financial crisis, which increased the salience of economic issues.

Using the American National Election Studies, Stonecash (Reference Stonecash2017) shows that class voting in presidential elections held steady from the 1950s until after the financial crisis. Since the 2008 election, the white working class has shifted significantly from the Democratic Party to the Republicans, culminating in the election of Donald Trump. The shift is so stark since 2008 that it is safe to say an inversion occurred. Zingher (Reference Zingher2019) builds on Stonecash's finding to show that the defection of college-educated whites from the Republicans to the Democrats was the most pronounced change from the 2012 to 2016 elections and that social class was one of the primary determinants in white vote choice for Trump (Zingher, Reference Zingher2020). In the European context, Stubager's (Reference Stubager2013) survey experiment found that the low education levels of the working class are a key mechanism for their movement from the Danish Social Democrats to the far right Danish People's Party. Similarly, Oskarson and Demker (Reference Oskarson and Demker2015) find that the Swedish working class's greater authoritarian leanings and lower political trust account for their recent movement away from the social democrats to the far right.

International trends in changing working-class voting is interesting for Canadian scholars because it invites us to consider the question of working-class conservativism. This phenomenon was identified so presciently by Lipset but has been largely hidden as Canadian political scientists either looked for a relationship between the working class and the NDP or emphasized the strength of brokerage politics organized along cleavages of region, religion and language. In Canada, there is some evidence of weaker support for racial minorities by working-class voters in the late 1990s (Brym et al., Reference Brym, Veugelers, Butovsky and Simpson2004) and of partisan polarization around immigration to drive “ordered” voters to the Conservative Party more recently (Graves and Smith, Reference Graves and Smith2020).

Once one takes on board the importance of multidimensional political competition and how it can contribute to reversing Lipset's long-standing relationship between the working class and the left and upper classes and the right, then it becomes apparent why an investigation into class voting might be merited. Although Andersen (Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013) found a mismatch between an increasing emphasis in new politics issues through to 2000 without a corresponding switch in the class basis of support for the left or the right, it may take voters longer to integrate these changes into their vote choice. Cochrane (Reference Cochrane2015) found that although a left-right gap opened up between the Progressive Conservatives and the other parties in the 1980s, a clear left-right divide in voter attitudes was not fully established until the 2000s. Thus, there apparently exists a lag of several elections between changes in party positions and voter attitudes.

However, Cochrane's analysis employed a unidimensional conception of left and right. We have noted other evidence that indicates the rise of a second dimension (Achterberg, Reference Achterberg2006; Andersen, Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013). It is not hard to see that the issues that separated right from left were distinctly different in the 1990s, 2000s and 2010s, as they were from the 1970s and 1980s. The 1990s were dominated by the Liberals, who moved to the right economically, making welfare retrenchment and deficit cuts central to their platforms (Banting and Myles, Reference Banting and Myles2013). Then a series of elections was fought almost entirely over the question of gay marriage between 2004 and 2008. While there were concerns about the economy expressed in the wake of the global financial crisis (Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Jenson, LeDuc and Pammett2019), these were joined by many concerns around immigration (Banting and Soroka, Reference Banting and Soroka2020).

These, as well as the more pronounced comparative literature findings, invite us to examine how working-class Canadians have related to the new Conservative Party of Canada. There is potentially a great deal at stake here. Specifically, is Canada prone to the phenomenon of working-class authoritarianism? If a weak but not absent working-class preference for the NDP continues to exist, then perhaps not. But if the Canadian working class is shifting its support, possibly to the Conservatives, then this becomes a possibility in the future. Therefore, this article sets out to study what might be driving working-class conservativism by analyzing working-class voting and how working-class respondents’ issue positions align with their partisan choices. This allows for a consideration of Canada within broader debates on the changing class bases of contemporary parties and their relation to populism and nativism.

Hypotheses

Informed by the literature, four hypotheses are tested in this article:

H1: The historic pattern of class voting in Canada is consistently weak but not absent, as measured through working-class voting for the NDP.

H2: Working-class voting for the right in Canada has increased over time and is most pronounced in recent elections.

H3: The primary driver of working-class voting for the NDP occurs along the economic dimension, most notably among support for redistribution.

H4: The primary driver of working-class voting for the right occurs along the cultural dimension, most notably and increasingly among attitudes toward moral traditionalism and immigration.

Data and Methodology

To examine class voting in Canada, this study uses merged data from the entire series of the Canadian Election Study (CES). Our dataset comprises all 17 federal elections from 1965 to 2019, containing an average of roughly 3,000 respondents per election. For consistency, we use the face-to-face and telephone mode of interviews throughout.

We employ exploratory graphical techniques and statistical models to test our hypotheses. We undertake both multinomial logistic and ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions for estimating party voting. In all analyses, the dependent variable is the reported vote choice from the post-election wave of each CES. They are produced for each main party: Liberal, Conservative, NDP and Bloc Québécois (BQ). Conservative vote is the amalgamated vote of right-wing parties that split off or merged with the Conservative Party—including Reform (1987–2000), Canadian Alliance (2000) and the People's Party (2019).

We rely on a range of standard demographic controls known to influence vote choice in Canada (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Cutler, Soroka, Stolle and Bélanger2013; Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Neville, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012; Johnston, Reference Johnston2017; Nevitte et al., Reference Nevitte, Blais, Gidengil and Nadeau2000). Education is measured as a dummy variable coded 1 for degree holders. Age is included as a continuous variable.Footnote 2 A gender voting cleavage has also appeared, with women more likely to support the left (Gidengil et al., Reference Gidengil, Neville, Blais, Everitt and Fournier2012). Similarly, union Footnote 3 membership has been linked to left party support (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Blake and Dion1990). Therefore, male and union dummy variables are included. Household income is measured in quintiles (low to high).Footnote 4 To reflect Canada's pronounced regional cleavages, region is coded as a four-category variable (Atlantic, Ontario, Quebec and West). Religion has historically featured prominently in Canadian vote determinants, with a pronounced cleavage existing between Catholics and Protestants, although it has weakened in recent years with the cleavage now centring around secularism (Wilkins-Laflamme, Reference Wilkins-Laflamme2016). Thus, religion is a categorical variable measuring: (no religion, Catholic, Protestant, and other).

Following Andersen (Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013), we code class according to a modified version of Erikson and Goldthorpe's (Reference Erikson and Goldthorpe1992) class schema consisting of four categories (professional, manager, routine non-manual, and working class).Footnote 5 Where possible (for example, since 1979), we add the self-employed as a fifth category, regardless of self-reported occupation, as they have been associated with voting for the right (Barisione and De Luca, Reference Barisione and De Luca2018). In both constructions of occupation, working class is also coded as a dummy. To construct these class categories, we relied on pre-existing categories provided in some of the early CES files. This stopped in 2006, so for the remaining files, we used Statistics Canada's National Occupation Classification (NOC) system. This matrix of occupations distinguishes two dimensions for occupations: skill level and skill type. Managers and professionals were distinguished by all those in the managerial and the professional skill levels (skill levels A and B, respectively). The managerial category thus includes anyone with self-reported managerial authority across the different skill types, including, for example, school principals but also managers in manufacturing, retail or sales sectors. The professional category includes nurses, teachers, university professors, judges and social workers. The working class was defined as workers in skill levels B, C and D and occupational categories 7, 8 and 9. This effectively combined skilled and unskilled working-class occupations, including boilermakers, ironworkers, and delivery and courier drivers. The routine non-manual class was defined as being in skill levels B, C and D but in occupational categories 1 through 6 (Statistics Canada, 2021). This includes occupations such as property administrators, executive assistants, legal administrative assistants and retail salespeople. We used the most recent version of the NOC for each survey.

While acknowledging that social class can be measured through multiple markers, such as income, education, or union membership, there remain good grounds to keep occupation as a basis for class analysis. For example, Kitschelt and Rehm (Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014) used a measure of social class that categorized occupations along two dimensions: a hierarchy of authority and a logic of task structures. After controlling for income, education, sectoral affiliation, union membership, and other demographic controls, they found that class membership had noticeable effects on political preferences over redistribution and citizenship. Our measure is similar to Kitschelt and Rehm's in that it recognizes the way in which social classes are distinguished by their hierarchical position, but it also partially distinguishes social classes in terms of the task type. Our working-class occupations are all clustered in skill types that deal with things, while our routine non-manual class are all clustered in occupations that deal with people and information. In addition, by adopting this modified Erikson-Goldthorpe-Portocarero (EGP) scheme based on occupation, we can partially replicate and extend Andersen's (Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013) work on social class and vote choice in Canada to consider the relationship between social class and vote from 1965 to 2019.

We also include core attitudinal beliefs and values in our models. The CES did not begin to consistently measure attitudinal beliefs until the 1980s; therefore, we construct these variables from 1993 to 2019. We construct two indexes based on the dominant spheres of political conflict —the economic (state-market) and socio-cultural (authoritarian-libertarian) dimensions. Market liberalism measures the economic dimension via two questions: “the government should leave it to the private sector to create jobs” and “people who do not get ahead have only themselves to blame.” Moral traditionalism measures the libertarian-authoritarian dimension via a question pertaining to gender roles and another question on attitudes toward homosexuals.Footnote 6 For the economic dimension, we include respondent's support for redistribution, which is highly correlated with social class position. The variable is based on variations of the question: “how much do you think should be done to reduce the gap between the rich and the poor in Canada.” Similarly, a key component of the socio-cultural dimension is also examined that includes views on immigration. They are measured via answers to a question asking whether immigration rates should increase, stay the same, or decrease. Each of the attitudinal variables are rescaled between 0–1 (left to right) for consistency. See online Appendix A2 for the full questions utilized in the attitudinal variable composition.

Results

Class voting

Following Andersen (Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013), we fit a multinomial logistic regression of vote in Canada on a four-category measure of social class with no controls. We fit this model separately for Quebec and the rest of Canada. Social class here is a four-category measure distinguishing managers, professionals, working class, and the routine non-manual. It would have been desirable to include a self-employed category, but this was not available prior to 1979 in the CES. Figure 1 presents the predicted probabilities for each party by social class for each election year.

Figure 1. Marginal effect (predicted probability) of occupation on voting for the four largest parties, from 1965 to 2019.

Overall, the class cleavage in Canada, evidenced by the gap between the lines, is weak but not absent. There is also a noticeable increase in support for the Conservative Party by workers starting in the 1990s. In Canada outside of Quebec, support for the Conservatives was lowest among working-class voters, but since 1993 that has changed dramatically, with the working class and managers becoming the most likely to support the party and with professionals and routine non-manual workers the least likely. Post-1993, the Reform-Canadian Alliance-Conservative electorate is a distinctly cross-class coalition of managers and workers, as opposed to the pre-1993 Progressive Conservative electorate dominated by managers. This is different for the Liberals. Working-class voters were as likely to support the Liberals as voters in other classes up until 1993; since then, working-class voters are the least likely to support them.

Turning to the NDP, working-class voters were more likely to support the party than any other class prior to 1993, and this has partially continued post-2004, although the party has added support from professionals and routine non-manual workers. The NDP has more support from working-class voters than the Liberals for most of this period. By contrast, managers have historically been the least likely to support the NDP, and this continues today. Nevertheless, the fact that the NDP has rarely won more than one in four working-class votes speaks to its limited ability to carve out a distinct class electorate in a country dominated by linguistic and regional divisions.

Three changes are worth noting in the NDP pattern. First, the party's growth in Quebec between 2004 and 2011 was not marked by a strong class character, as it appealed to a broad segment of Quebec society. Second, the party's growth in English Canada was not particularly marked by increases in class voting. Instead, the party added new voters in the non-working-class segments of the electorate, except managers. Third, the 2019 election demonstrated the weakest support for the NDP by working-class voters since its crisis in 1993, when the party only captured 9 per cent of the national vote and nine seats. There is an important difference between the two elections in that the electoral crisis of the 1990s was a cross-class crisis; the party lost support everywhere. But in 2019, the class character of the party's electorate changed substantially; it lost support specifically among English Canadian working-class voters while maintaining support in other segments of the workforce.

Turning to the Liberals, we note one distinct pattern: up to and including the 1993 election, in English Canada, the party lacked a distinct class character, exemplifying a brokerage party electorate. This started to change in 1997, as the party lost support specifically among workers, a gap that continued through the 2000s and up to the 2019 election. A similar gap in support between workers and other classes developed earlier in Quebec, starting in 1993.

For the Bloc, the working class and professionals were the occupational groups most likely to support them through to the 2004 election. Working-class support fell away as working-class voting for the Conservatives and the NDP spiked upward in 2006 and 2008, respectively. In 2015 and 2019, however, the working class again became the occupational group most likely to support the BQ. A supplemental analysis of support for the BQ by decade found a large increase in the relationship between anti-immigration attitudes and working-class support for the Bloc in the 2011, 2015 and 2019 elections, although the small sample size means that the observed relationship is not statistically significant. At the same time, the relationship between anti-immigration attitudes and working-class support for the Conservatives dropped. Readers can view the material in online Appendix A4.

We extend this analysis in Table 1, which presents a multinomial logistic regression of party vote on social class, controlling for age, religion, gender, and for Canada outside of Quebec, region. This is an extension of Andersen (Reference Andersen, De Graaf and Evans2013). Following that study, we use a multinomial logistic regression, except that we keep the Bloc Québécois and the NDP separate, on the grounds that the former is better conceptualized as a nationalist, rather than a leftist, party.Footnote 7 We also start in 1979, which provides two distinct advantages: it provides a historic comparison that overlaps with Andersen's analysis, but it also allows us to add the self-employed, who were absent in Andersen's study.

Table 1. Multinomial logistic models predicting party vote in Quebec and Rest of Canada, with key class-related controls for age, gender, region and religion.

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

What stands out when this model is compared with Andersen's results for the 1965 to 2004 period, is that there continues to be weak, but not absent, class voting in Canada outside of Quebec. Between 1979 and 2019, the NDP was more likely to win support from working-class voters than all other classes. The only hint of a class cleavage that exists in Quebec is that professionals show greater levels of support for the NDP than for conservative parties. This is an interesting finding because it covers years of NDP strength in Quebec, which seems to have been led by professionals. This demonstrates a distinctly different class basis of support than in the rest of the country.

That said, Table 1 does not provide any insight into how class effects on vote choice may have evolved over time. As a consequence, we investigate class voting further in the next section. To simplify the analysis, we fit OLS models to each of the three largest parties’ vote from 1979 to 2019. These models include both union status and a dichotomous variable indicating working-class status and controls for age, gender, income, region, and religion. Figure 2 shows the coefficients for union and working-class status. The support for the NDP by working-class voters identified in Table 1 and Figure 1 is clearly primarily support among unionized households. By contrast, support for Conservatives among union households is distinctly and consistently lower. While this is mostly stable for the NDP, there is some tentative evidence of decline in support for the NDP by voters in union households, with support dropping in 2015 and 2019 and reaching near historic lows in the latter. However, even controlling for union status, the NDP had a partial advantage among working-class voters, but this disappeared in the mid-1990s and partially reappeared in the 2008 and 2015 elections. However, there is a much more distinct pattern in working-class support for the Conservatives. That is to say, controlling for union status and other demographic variables, there is a clear increase in support among working-class voters. It is difficult to pinpoint exactly when support started to increase, but the working-class coefficient has been consistently above zero since 2006 and reached historic highs in 2019.

Figure 2. Coefficients from Canada-wide OLS models predicting party vote by working class, with key class-related controls for age, degree, gender, income, region, religion, and union status. Breaking down these results into Quebec and the Rest of Canada yields no distinct patterns. Support for the BQ in Quebec has little variation. A version of this graph that does distinguish between Quebec and the Rest of Canada is provided in online Appendix A4.

H1 largely holds until 2019, but it crucially runs through union status, as we consistently see weak but not absent class voting, especially outside Quebec, in our analyses. At the same time, we also see evidence for H2—increasing working-class support for the right in recent years—that then becomes significantly pronounced in 2019.

Drivers of class voting

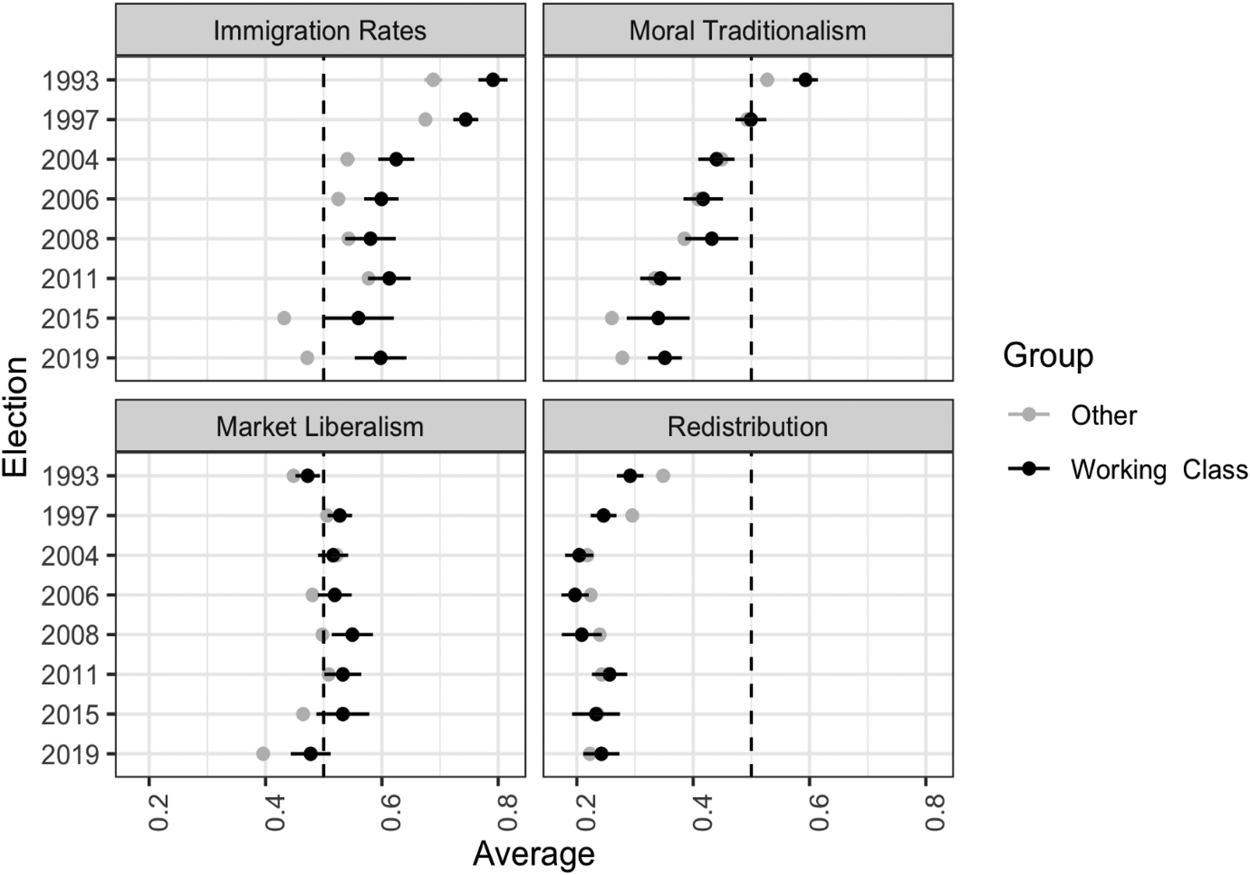

Turning to the drivers of class voting in Canada, we incorporate key attitudinal preferences that might link voters in a particular social class with a political choice into our analysis. Existing theory suggests that both economic and cultural voting is motivated by a particular set of attitudes (Houtman et al., Reference Houtman, Achterberg and Derks2009; Lipset and Rokkan, Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967). Below, we examine the nature of the changing class cleavage on several of these. Figure 3 presents the policy preferences by social class on several measures implicated in the literature on class realignment. Specifically, we include commitments to moral traditionalism, immigration, redistribution, and market liberalism. Respondent's scores are scaled such that negative scores are left-wing and positive scores reflect right-wing attitudes.

Figure 3. Mean attitudinal preferences over time for working-class versus rest of population. Scaled from left to right (0–1).

In general, Canadians have moved considerably leftward on both moral traditionalism and immigration and have moved slightly leftward on the economic dimension since the 1990s. What is more interesting is the relative position of working-class versus non-working-class voters. Although, non-working classes were more left-wing than working-class voters on cultural issues throughout the time period, they are also more left-wing than the working class on economic issues in recent elections, most notably on market liberalism. This pattern of preferences is opposed to what Lipset conceptualized, where workers would be more liberal on economic issues but more conservative on cultural issues.

We extend this analysis to explore whether and how these views are linked to vote choice for workers. We explore the phenomenon of drivers of class and cultural voting in this section: first, in a graphical and exploratory fashion, and second, in a more formal way. Figure 4 presents a series of panels that report the vote shares of working-class voters with supportive positions on the same four issues. We are searching here for issues where working-class voters divide the most. We notice a few patterns. First, the Conservatives consistently did best with working-class voters who held free market and morally traditional positions, carrying those voters in every election since 1997. The initial separation of the working class from the Liberals to the Conservatives appears to have been primarily on issues related to moral traditionalism. The level of support from working-class respondents concerned about immigration for the Conservatives was relatively stable at around 45 per cent, which increases dramatically in 2019. Second, we note the minimal separation on issues of redistribution; working-class voters opposed to redistribution spread their votes around much more than voters with conservative views on other issues. This suggests that the working-class voters are voting based on other preferences—in particular, second-dimension attitudes such as moral traditionalism and immigration. Third, in the years when the NDP did best (for example, 2011 and 2015), it won over voters who were more anti-immigration, which declined substantially in 2019. Given that the NDP did not run on an anti-immigration platform, this would suggest that anti-immigration attitudes do not automatically drive working-class voters to the Conservatives. The partisan sorting on immigration that Banting and Soroka (Reference Banting and Soroka2020, Reference Banting and Soroka2021) observe in post-2004 Environics surveys, with those opposed to higher immigration rates supporting the Conservatives, is visible among working-class respondents for the CES but is somewhat contingent on the specific electoral context.

Figure 4. Party vote shares of working-class voters with supportive attitudinal positions on a series of key issues over time.

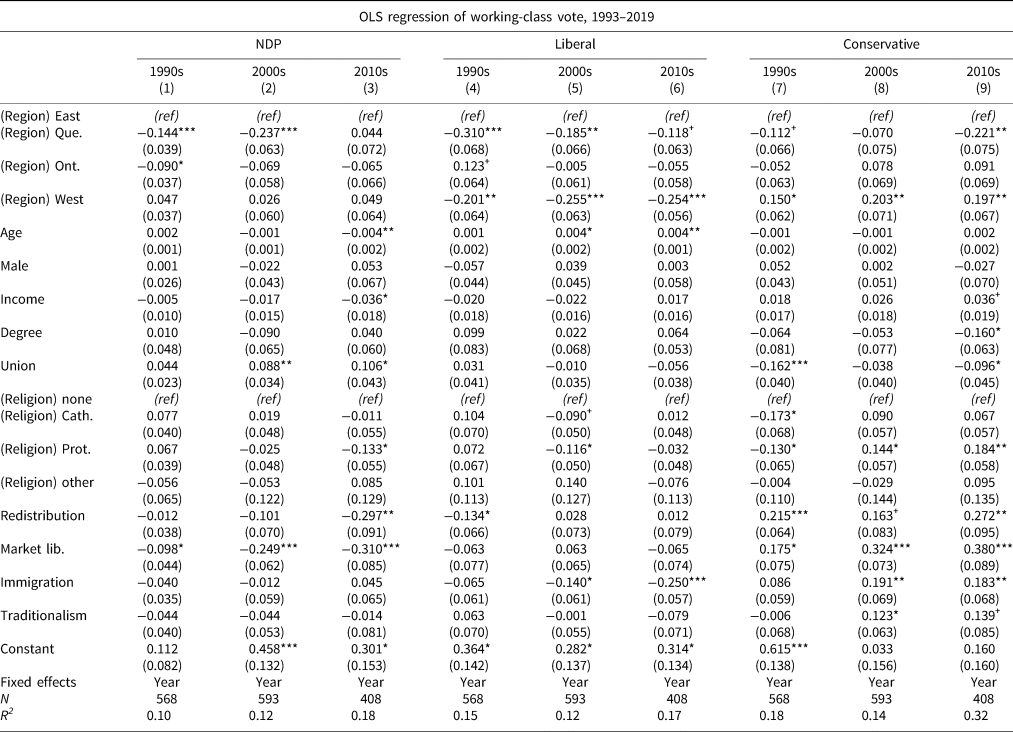

To more precisely determine how attitudinal preferences are linked to class voting, we undertake estimations on a working-class subsample from the CES. Table 2 presents the pooled results of nine OLS regression models fit for each major national party. We fit each model by decade 1993 to 2019, with year fixed effects. Each model includes controls for age, degree, gender, income, region, religion, and union status.

Table 2. OLS models predicting party vote of the working class, with key class-related controls for age, gender, income, region, religion, and union status. A subsample of Quebec only is provided in online Appendix A5.

+ p < .1; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

We emphasize the following findings. First, demographic characteristics of working-class party voting exhibit much less significance or change across the time periods, compared to attitudinal preferences. However, younger segments of the working class now significantly vote NDP, along with union members, and lower-income earners. Second, economic attitudes are a very poor predictor of Liberal support, whereas it is a strong predictor for both the NDP and Conservatives, which increases substantially in recent elections, especially for the NDP. Third, redistribution has increasingly become a strong predictor of NDP support. It exhibited little effect in the 1990s, some strength in the 2000s, and reaches statistical significance in the 2010s at (p < .01). Fourth, moral traditionalism has changed directions for both the Liberals and Conservatives. Moral traditionalism was positively related to Liberal support in the 1990s, had basically a null effect in the 2000s, but was negatively related in the 2010s; whereas the Conservatives, surprisingly, did better among the non-morally-traditional working class in the 1990s, but since then, moral traditionalism has become a significant predictor of working-class Conservative support. This finding aligns with recent research documenting how the new Conservative Party of Canada has consolidated morally traditional voters into its base (Bélanger and Stevenson, Reference Bélanger, Stephenson, Lewis and Everitt2017; Wilkins-Laflamme and Reimer, Reference Wilkins-Laflamme and Reimer2019). Fifth, immigration was a poor predictor for all three parties in the 1990s, but since then, pro-immigrant sentiment displays an increasingly significant effect on Liberal support, while anti-immigrant sentiment is nearly equally as strong for the Conservatives. Last, the model fits (as measured via R 2) are similar for the NDP and Liberals over time, with the Liberals seeing a marginal increase. However, Conservative model fit is similar to the NDP and Liberal range until the 2010s, where we then see a dramatic increase to an explanatory power of 32 per cent, which is also nearly twice as large as for the NDP and Liberals. This finding suggests that Conservative vote patterns are largely driving the working-class realignment that we find post-2000, which displays the biggest increased effects via the cultural dimension.

In sum, the biggest changes in working-class voting occur in the cultural realm, as the ideologically economic bases of support for the NDP and the Conservatives simply hardened. We do find support for H3, that working-class NDP support is consistently mobilized from the economic dimension. The link between working-class voters’ economic preferences and their support for the NDP has become more pronounced, especially in support for redistribution. Similarly, we find support for H4, that the primary driver of working-class support for the right occurs along the cultural dimension. Whereas prior to 2000, working-class Conservative voters were no more conservative than the average Canadian on the cultural issues of moral traditionalism and immigration, they were significantly so after 2000. Post-2000 marks a watershed, whereby culturally right-wing members of the working class gradually abandoned the Liberals and NDP for the Conservatives. And of the four attitudinal values included in the article, the NDP was only able to attain pro-redistribution members of the working class (albeit only a quarter of them).

Conclusion

In this article we have examined class voting in Canada. Research in other political systems has highlighted the return of Lipset's cross-pressured working-class voter, increasingly drawn to parties of the right for their authoritarian or anti-immigration cultural claims. What might that mean for Canada, where a “weak but not absent” class cleavage had been long overshadowed by religious and linguistic cleavages? Will this new cultural voting wash away what little class voting was present?

We started by observing that the NDP has maintained a moderately distinct base, drawing on the persistence of a “weak but not absent” class cleavage. While the Liberals’ working-class vote gradually withered away and the Conservatives’ vote grew, the NDP held their own. Class consistently remained a predictor of support for the NDP outside Quebec, although this operated largely through unions. Overall, we found support for our first two hypotheses of continuity in the presence of a weak working-class vote for the NDP and growing working-class voting for the Conservatives.

We then analyzed the drivers of class voting in Canada, finding that there has also been a widening gap between workers and other classes in their policy preferences on immigration rates and moral traditionalism. Consistent with our third and fourth hypotheses, we found that it was this cultural dimension that most strongly bound workers to the Conservative Party, while redistribution has increasingly bound workers to the NDP. This is consonant with the view that working-class conservatism is a cultural phenomena tied to values of personal responsibility and social order (see also Graves and Smith Reference Graves and Smith2020).Footnote 8 We interpret these trends to agree with Dutch research by Houtman et al. (Reference Houtman, Achterberg and Derks2009), which argues that class voting (for example, voting based on group self-interest for economic reasons) is largely distinct from cultural voting (for example, voting opposed to group self-interest for non-economic reasons) and that the two can oddly coexist in a party system.

The standard narrative of the Canadian political party system (Carty et al., Reference Carty, Young and Cross2000) has the Liberals and the Conservatives trading votes without much of a class appeal and with the NDP valiantly trying to break up that duopoly. Our evidence complicates that narrative. On the one hand, despite the power of the Liberal and the Conservative duopoly, the NDP did build a stable working-class electorate, primarily through its relationship with trade unions. However, with the implosion of that party system in 1993 (Koop and Bittner, Reference Koop, Bittner, Bittner and Koop2013), Liberal working-class support has dwindled. This has freed up blocks of working-class voters, and our evidence demonstrates that the conservative party family has absorbed most of them, especially since 2004, primarily based on concerns associated with immigration and moral traditionalism. These trends are consistent with Banting and Soroka's (Reference Banting and Soroka2021) suggestion that a stronger nativist cleavage may be emerging as a confluence of partisan sorting on immigration and a growing willingness of Conservative politicians to mix cultural threat messages in with their traditional support of immigration as an economic good. They also mirror the dynamics that Norris and Inglehart (2019) and others observe globally, making the study of authoritarian populism a promising avenue for future research.

This new situation provides distinct challenges for the Conservatives and the NDP. While many European social democratic parties have seen their voting base implode as many workers follow the anti-immigration appeals of the right and more than a few gravitate to new left parties, such narratives of Pasokification fit the NDP poorly. After all, its recent results are in line with those of the 1970s and 1980s, and our analysis shows a continued appeal to the unionized working class and even a strengthening appeal among egalitarians and low-income earners. The challenge for the NDP would be that attempting to counter Conservative appeals to working-class votes by moving rightward on cultural issues would drive part of their electorate to the Liberals. For Conservatives, the way to expand working-class support is to woo unionized workers. This may require pro-labour messaging that sits uneasily with the market liberalism of the party's core voters. Erin O'Toole's outreach to unionized workers in his 2020 Labour Day message and in the Conservative Party's 2021 platform, as well as unhappiness within the party with that outreach, illustrate this challenge.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423922000439