CLINICIAN’S CAPSULE

What is known about the topic?

Injuries from non-powder firearms are common and potentially life-altering. The Canadian Pediatric Society urges stricter controls on non-powder guns.

What did this study ask?

What are the Canadian contextual trends in paediatric firearm injuries?

What did this study find?

In this study, the rate of paediatric firearm injuries was stable from 2006 to 2013. Eye injuries inflicted by non-powder firearms were most common. Most firearm injuries occurred through recreation and sport.

Why does this study matter to clinicians?

Parents who receive physician counselling about firearm safety report change in practice. This study highlights settings/individuals that may be appropriate targets for intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly one Ontario youth is injured each day by a firearm.Reference Saunders, Lee and Machperson 1 The Canadian Pediatric Society (CPS) has urged stricter controls on non-powder guns powerful enough to penetrate tissue.Reference Austin and Lane 2 Injuries from non-powder firearms (guns that do not use gun powder such as BB, pellet, or airguns) are usually non-lethal but may be life-altering.Reference Lee and Fredrick 3 In the United States, airgun injuries accounted for 10% of sport-related eye injuries, 26.4% of which caused impaired vision.Reference Haring, Sheffield, Canner and Schneider 4

The Canadian Hospitals Injury and Reporting Prevention Program (CHIRPP) is a richly detailed national database of “pre-event” injury data. Data come from questionnaires completed by patients and staff in 11 pediatric emergency departments (EDs) and 6 general EDs. Coders abstract data elements from patients’ narratives.Reference Crain, McFaull, Thompson and Skinner 5 We aim to describe contextual trends in firearm injuries in Canadian children.

METHODS

This is a registry study of ED visits for children ages 0 to 18 years with firearm-related injuries captured by CHIRPP. Firearm injury cases from 2006 to 2016 were extracted by the CHIRPP data and research manager (Ottawa) through a database query for records with any of the following codes: “Gas, air or spring-operated guns, INCL BB guns, pellet guns”; “Guns, firearms and rifles, NEC”; “Gunpowder, ammunition and explosives, INCL bombs”; “BBs and pellets”; “Firearms, INCL airguns, BB guns, rifles, handguns and flare guns”; and “Intentional self-harm by rifle, shotgun, handgun, or other firearm.” The query also captured records containing any of these keywords: BB (and punctuation variations), pellet, gun, shot, shoot, scope, rifle, firearm, firearm, pistol(e), revolver, bullet, trigger, airsoft, air soft, coup de feu, arme a feu, arme à feu, fusil, and carabine. The total number of encounters per year for all injuries was determined to provide denominators for gun injury rates per 100,000 ED visits.

Exclusion criteria were age>18 years, lacking sufficient descriptive information to determine whether the injury resulted from firearm use, and injury description that was not consistent with firearm use. The patient narratives for each case in the dataset were hand searched by two authors to find cases that should be excluded. Variables extracted for comparison included age, sex, year of injury, nature of injury, context of injury, type of firearm, and injured body part. The dataset was truncated after 2013 due to missing data to allow for comparable calculated firearm injury rates. All analyses were done using R version 3.2.2.

RESULTS

The dataset provided by CHIRPP included 667 cases, and 255 cases were excluded: cases occurring after 2013 (n=108), age>18 years (n=143), insufficient data to verify firearm injury (n=1), and description not consistent with firearm injury (n=3) (Figure 1). We analysed 412 firearm injuries: 325 injuries by non-powder firearms, 80 injuries by powder guns, and 7 injuries by an unknown firearm. Most injuries resulted from a projectile: 95% (n=309) of non-powder firearm injuries and 84% (n=67) of powder gun injuries (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Total number of CHIRPP cases for study eligibility by firearm type and mechanism of injury.

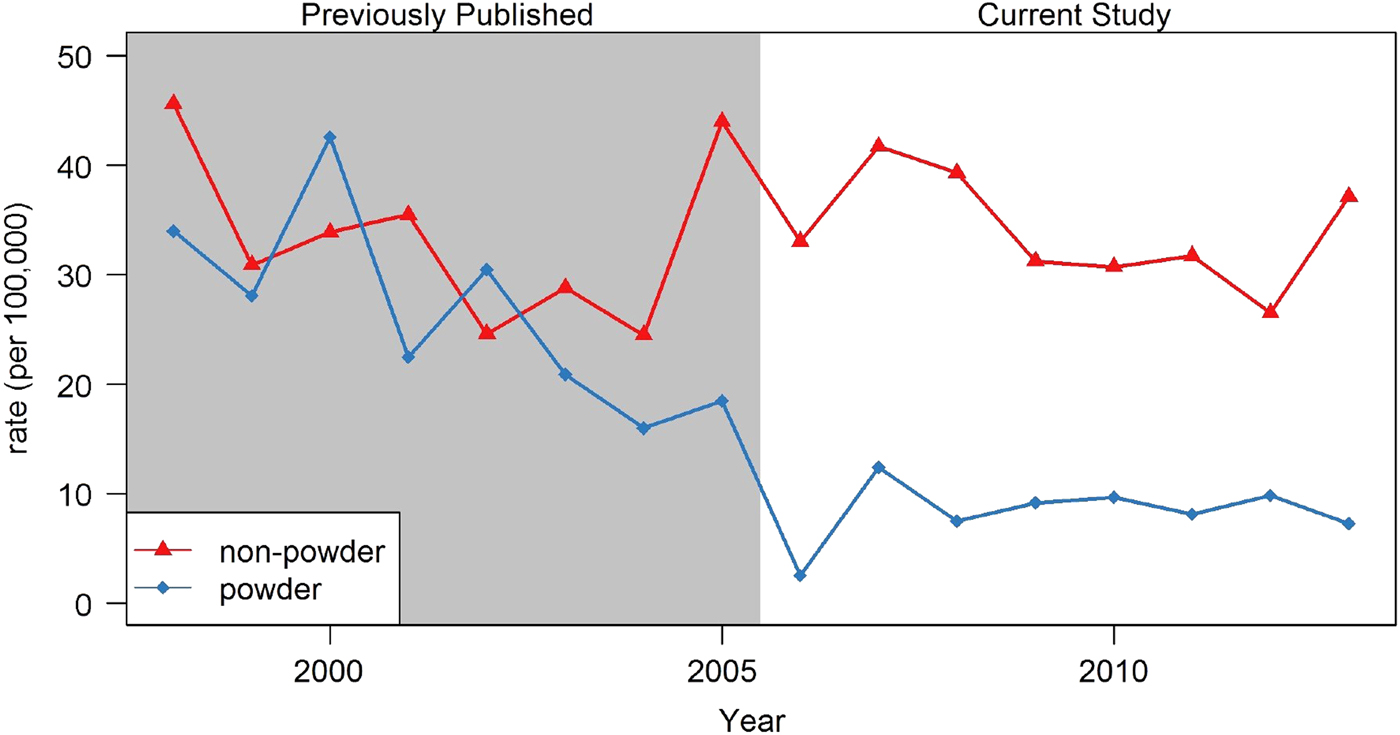

Figure 2. Rate of firearm injuries per 100,000 CHIRPP ED visits, by firearm type.

The number of firearm-related injuries per 100,000 ED visits remained stable from 2006 to 2013 overall (Figure 2). The age groups in which injuries occurred most often were 10 to 14 years and 15 to 18 years with a male predominance (80.5%, n=359). Most injuries occurred unintentionally by non-powder firearms in the context of recreation (disorganized physical activity; n=179) and sport (organized physical activity; n=48). Eight of nine instances of intentional self-harm were from a powder gun (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographics and context of firearm injury, by firearm type.

Overall, 45 individuals required admission to the hospital, and 2 died in the ED. Forty-three percent of injuries from non-powder firearms required treatment (n=130) or admission (n=11) (Table 2). Eye injuries were the most common injury (n=150) with 98% from non-powder firearms. The use of protective eyewear was noted in 12 instances. Overall, the “external cause of injury” was “a child or adult other than the victim” in 149 cases.

Table 2. Disposition of patients with firearm injuries, by firearm type.

DISCUSSION

Non-powder firearm injuries continue to raise concern with reports of vision loss and even death.Reference Lee and Fredrick 3 , Reference Veenstra, Prasad and Schaewe 6 , Reference O'Neill, Lumpkin and Clapp 7 Our study demonstrates that firearm injuries have remained stable from 2006 to 2013, despite the cancellation of Canada’s long gun registry and an increase in airgun sales and related injuries in the United States.Reference Lee and Fredrick 3

Eye injuries from non-powder firearms were the most common in our dataset. In the United States, these injuries are the leading cause of pediatric eye injuries requiring admission.Reference Lee and Fredrick 3 There are at least 56 published cases of vision loss after a non-powder firearm injury.Reference Lee and Fredrick 3 There is little to indicate that protective eyewear would prevent vision loss in these cases, but given that many of the victims are persons other than the “shooter,” use of protective eyewear for the shooter may not help.Reference Haring, Sheffield, Canner and Schneider 4

Parents who receive physician counselling about firearm safety report higher rates of handgun removal and safer storage.Reference Garbutt, Bobenhouse and Dodd 8 More research is needed to determine whether physician counselling is similarly effective for non-powder firearms, which are largely viewed as toys. While the context of firearm-related injury in the United States differs from Canada, studies comparing pediatric injury according to the stringency of state firearm laws suggest that legislation matters.Reference Safavi, Rhee and Pandit 9 , Reference Tashiro, Lane and Blass 10 Classifying higher velocity non-powder firearms under Canada’s Firearms Act and bringing lower velocity non-powder firearms under the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act,Reference Veenstra, Prasad and Schaewe 6 as advocated by the CPS, may diminish these injuries.

LIMITATIONS

Data extraction was performed by a single data extractor and reviewed by two authors to ensure that included cases were appropriate. We were not able to assess cases that may have been erroneously excluded. Most CHIRPP data come from hospitals in cities so injuries of older teenagers, First Nation and Inuit people, and inhabitants of rural and remote areas are underrepresented. CHIRPP also underrepresents fatal injuries as it does not capture prehospital deaths.Reference Herbert and Mackenzie 11 Injuries in patients who refused to complete the data collection form are also missed.Reference Mackenzie and Pless 12

CONCLUSION

Overall, the rate of firearm-related injuries in children and youth presenting to participating CHIRPP EDs was stable from 2006 to 2013. Eyes were most commonly injured, and these were most often caused by non-powder firearms. Most injuries occurred during sport and recreation and were inflicted by someone other than the victim, highlighting settings and individuals that may be appropriate targets for intervention.

Acknowledgements

Data used in this publication are from the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP) and are used with the permission of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Thanks to Jennifer Crain of PHAC for creating the dataset. The analyses and interpretations presented in this work do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the federal government.

Competing interests

None declared.