Introduction

Assent is described by the Ethics Working Group of the Confederation of European Specialists in Paediatrics as “a child’s agreement to medical procedures in circumstances where he or she is not legally authorised or lacks sufficient understanding for giving consent competently.”Footnote 1 It has been claimed that, by seeking agreement, assent fosters autonomy and moral growth, and improves decision-making skills.Footnote 2 Although assent is most prominent in pediatric bioethics, it is advocated in numerous contexts, both legal and ethical, where we cannot effectively seek consent. The idea of seeking assent in these circumstances may be intuitively attractive to many, yet the concept of assent lacks detail and might be interpreted in very different ways.

Receiving assent from children for their participation in research is legally recognized in a number of jurisdictions. The United Kingdom (UK) research regulator, the Health Research Authority,Footnote 3 augments UKFootnote 4 and European Union (EU) law,Footnote 5 and all research involving children must seek assent. In bioethics, assent is increasingly proposed to advance a liberating agenda to those who ostensibly lack the ability, legal or otherwise, to make autonomous choices. Although originating in research, assent is advocated in the treatment of both children and people with dementia. Within research, assent has also been advocated in diverse populations including people with disorders of consciousness and animals used in research. In this article, after exploring the origins of assent, I ask how assent is conceived in the treatment of, and research with, both children and people with dementia. A variety of justifications are suggested for assent. These include the contention that assent will benefit under-researched groups, enhance individual autonomy, educate in decision-making, allow paternalistic protection of the welfare, and prevent or reduce harm. All of these justifications are found in children’s research and almost all in children’s treatment, but fewer in dementia treatment and research. In some interpretations, these justifications may be consistent. Yet depending on their relative weight and interpretation they may suggest contradictory inclinations, and I question their ability to provide a footing for a consistent use of assent. Since assent is sometimes claimed to be a moral augmentation of the law,Footnote 6 a more rational approach to assent may be to consider the background legal conditions in particular jurisdictions or national contexts. For example, assent in children may have a role to play in the United States, where it may answer what some critics perceive as a national deficit in children’s rights.Footnote 7 , Footnote 8If this seems too parochial an approach, a grander ambition may come from making a common cause between the use of assent and the international agenda to reconceive decision-making in line with the approach advocated in the U.N. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Assent may currently lack a firm grounding that would promote consistent use, yet the promise of assent in offering recognition to members of otherwise marginalized and misused populations remains intriguing. I conclude by calling for the development of firmer theoretical foundations for assent to help meet this challenge.

Before proceeding I should note that my discussion inevitably considers the inverse of assent, that is “dissent.” While the nature of dissent potentially remains as ambiguous as assent,Footnote 9 I do not delve deeply into the concept of dissent to avoid hopelessly lengthening this discussion, instead considering it as the simple opposite of assent. Secondly, it is pertinent to address potential terminological misunderstandings around the terms “capacity” and “competence,” which are often used to describe decision-making ability. “Capacity” and “competence” have distinctive philosophical meanings.Footnote 10 Moreover, they have different meanings in different legal jurisdictions.Footnote 11 For example, English legal parlance uses the term “capacity” in the civil law only. Therein, “capacity” generally pertains to adults and encompasses the decision-specific test found in the Mental Capacity Act 2005. “Competence,” meanwhile, relates to a test of children’s decision-making maturity found in the common law. In the United States “competence” is employed within legal terminology in both civil and criminal law,Footnote 12 while “capacity” is reserved as a bioethical and medical concept.Footnote 13 This paper generally uses the terms capacity/incapacity to describe the ability/inability to make decisions. As my focus is on decisions within medical research and treatment, I include disease, immaturity, and lack of legal empowerment as reasons a person may lack capacity. Thus, by incapacitated individuals, I include children (who may well have unimpaired reasoning but face legal and other barriers to their decision-making) as well as adults with an acquired or congenital inability to make decisions.

Binary Approaches to Incapacity and the Emergence of Assent

Classic approaches to decision-making in bioethics take a binary approach hinging on an individual’s ability to make a decision. Those with decision-making capacity exercise their autonomy. Those without capacity have a decision made on their behalf, according to their best interests (howsoever these are constituted—although, from the perspective of contemporary English law, “best interests” do include a consideration of the views and wishes of the child or adult concerned, and thus arguably move toward the middle ground where these views and wishes can be ascertained). Yet this binary approach risks doing a disservice to those who have some decision-making ability but lack the ability for independent decision-making at all times, either due to immaturity (such as children), fluctuating capacity (such as adults with certain disorders or diseases) or where complex communication is impossible (adults with some disorders of consciousness or sentient animals). Depending on the degree we prioritize a liberal commitment to respecting autonomy in healthcare (and I shall not unpack this challenging question here), this entails finding some way of addressing the perceptions, preferences, and choices of incapacitated people. Various remedies exist, that may be more or less acceptable in one group or another. These include: following antecedent instructions drawn up by the individual; allowing family members to decide on a relative’s behalf or; calling on an experienced professional to make a substituted decision based on the individual’s likely wish. Whatever their merits, these solutions share a common weakness. Even when exercised in good faith, they fail to address the individual’s own current perceptions, and thus are mere approximations of choice. Problems addressing the needs of these groups are evident in clinical practiceFootnote 14 , Footnote 15 and are the topic of legal research.Footnote 16

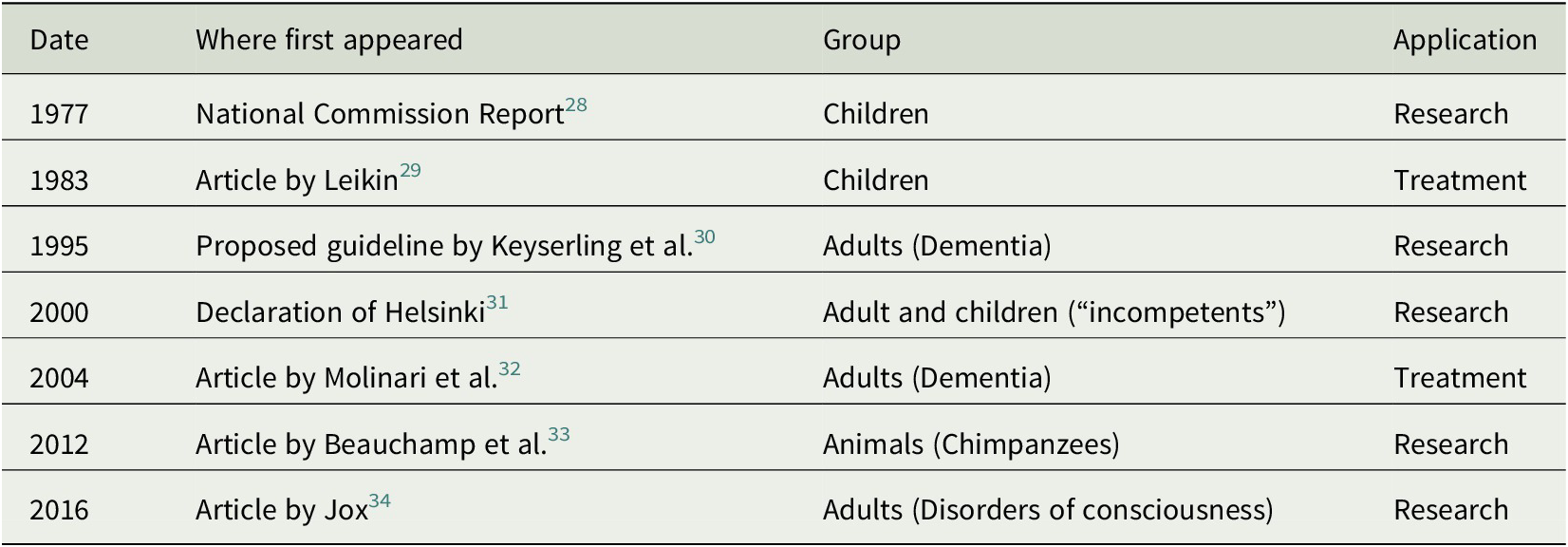

Assent first emerged as a bioethical concept in the 1977 report by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research published in the United StatesFootnote 17 (hereafter: “National Commission report”). It seems likely that its conceptual roots lie in U.S. tort law, where informed consent was at one time considered to comprise “awareness” and “assent.”Footnote 18 Assent was recognized in U.S. law in 1983,Footnote 19 and in EU law in 2014 (European law recognizes, rather than prescribes assent).Footnote 20 This statute is narrowly focused on research with children, but there is a growing body of literature and quasi-regulation in other contexts. Sanford LeikinFootnote 21 first proposed that assent might be germane to children’s treatment, and assent has been embraced for this purpose by the American Academy of Paediatrics Committee on Bioethics.Footnote 22 Guidelines for research with adults with impaired capacity include discussions of assent,Footnote 23 and since 2000 assent has been included as a requirement for research with those lacking decision-making capacity in the Declaration of Helsinki.Footnote 24 Assent has been proposed for treatment decisions with incapacitated adults.Footnote 25 More recently, assent has been discussed in animal researchFootnote 26 and research with patients with disorders of consciousnessFootnote 27 (Table 1).

Table 1. First Appearances of Different Applications of Assent

Despite the widespread invocation of assent, little conceptual work has yet occurred. Indeed, assent may be justified in ways that leave much open to question. For example, in research with children, studies commonly suggest that assent contains elements akin to the need for information, understanding, and voluntariness.Footnote 35 , Footnote 36These elements suggest a prima facie link with consent, yet raise the question of whether assent is something distinct or just consent by another name (indeed this substitution has been explicit in some, albeit revisionary, accounts of assent).Footnote 37 Assent has now been proposed in very different contexts. We must reflect on how differences in medical treatment and research environments, and a focus on adults or children, affect interpretations of assent (if at all).

Group Benefits of Assent

While assent is proposed for children in treatment settings,Footnote 38 assent is primarily discussed in the context of research. Much of the literature sees refusing assent as a protective mechanism by which children can object to participation in research.Footnote 39 Children may also be motivated to take part in research to help other children,Footnote 40 , Footnote 41or later come to appreciate their participation in research as they mature.Footnote 42 Potentially, by allowing children’s wishes to be involved in research to be heard, assent may also be viewed as a way to meet this presumed preference of children to participate in non-beneficial research. It may be countered that flaws in children’s understanding render assent of insufficient moral weight to agree to participate in non-beneficialFootnote 43 or higher-than-minimal risk trials.Footnote 44 Such arguments are not universally accepted. Anna Westra, Jan Wit, Rám Sukhai, and Inez de Beaufort propose accepting assent in order to facilitate research in children where studies are of exceptional value to children’s health at large.Footnote 45 They do so not because they believe assent is a sufficient standard of children’s understanding but because assent will facilitate research that will benefit children as a group. Perhaps perversely, such a view apparently conceives assent as a way to reduce the protection of individual children. Indeed, it chimes with critical views that assent is part of a capture of the child research agenda by commercial concerns of the pharmaceutical industry.Footnote 46 , Footnote 47

Assent has gained prominence at a time when the impact on children of the historical lack of research on children’s medicines is a rising concern.Footnote 48 , Footnote 49 , Footnote 50 Governments have addressed these concerns by passing laws to incentivize research in children. Incentives to reward drug companies that conduct research in children include valuable extensions to patents. Yet critics note that pharmaceutical studies in children have therefore disproportionately focused on medicines for diseases that are nearing the end of their patent periods, which are rare in children, but common in adults.Footnote 51 Critics argue that (inasmuch as they experience duress for no benefit) this concession has harmed children as a group. In such a situation assent may be viewed in two ways. Refusal of assent may offer additional protection to children against their exploitation, or, by reducing the barrier of need for consent, assent may represent a concession to drug companies to reduce the difficulties in conducting pediatric trials. While the former position sees assent as protective of the individual child, the latter position can still be justified with reference to group benefits. Thus by taking an explicitly collectivist motivation that focuses on accounts of what is good for children at large, assent may assume a quite different character to a more empowerment-led standard. Indeed, since non-therapeutic research itself is clearly aligned to collective benefits, it is unsurprising that a collectivist case for assent in children’s research can be made out.

Assent in children’s clinical treatment is much less discussed than research, and the putative benefits it offers in this context much less clearly fit the collectivist mold. For example, assent has been argued to protect children’s rightsFootnote 52 and/or reflect the intrinsic good of respecting children as persons.Footnote 53 These are concepts that ultimately embrace the broader extension to children of the group benefits adults enjoy (where the prevailing conception of benefit accepts the priority of the good of having a refusal respected over any physical harm arising from refusal). Yet they more clearly confer putative benefit to the child as an individual. This is especially true of the rights justification, given the putative function of rights in protecting the individual from being harmed for the wider good. The small literature focused on assent in the treatment of dementia is silent on the concept of group benefits, but the link between research and collective benefit is, somewhat tenuously—made in the case of dementia research.Footnote 54 For example, some contend that research participation allows people with dementia to act altruistically or militates against negative stereotypes of incapacity.Footnote 55 These benefits might comfortably be construed as either collective or individual, but tend to be framed as the latter. Given the affinity of non-therapeutic research to a group benefit justification, the rather muted reference to group benefits is interesting. Perhaps it suggests that respect for adults as persons is more firmly entrenched in the bioethical discourse around dementia than similar discourse around children.

Autonomy and Consent

Assent is sometimes argued to respect the nascent autonomy of pediatric populations,Footnote 56 although this argument is regularly criticized.Footnote 57 , Footnote 58Nevertheless, since seeking consent is commonly held to be the gateway to autonomy,Footnote 59 there is a tellingly close resemblance (in form if not in function) between assent and consent in children’s treatment and research. For example, it is not uncommon for children to be encouraged to sign an “assent form” in a manner that mimics the procedures of seeking consent.Footnote 60 , Footnote 61 , Footnote 62

The tripartite model of informed consent holds that valid consent entails a patient: (1) being provided with the information they need to decide; (2) understanding that information; and (3) making a voluntary decision. These elements are all present in the literature on children’s participation in research, and numerous authors model assent on consent.Footnote 63 , Footnote 64 , Footnote 65 Children’s developmental level varies. Capacity is not simply a corollary of ageFootnote 66 and some emphasize that the way the information, understanding, and voluntariness manifest can vary from one child to the next.Footnote 67 While this lends a certain ambiguity to the presence or absence of assent, many reject the notion that assent is simple affirmation without understanding.Footnote 68 , Footnote 69Moreover, dissent in research is often held to warrant an outright veto.Footnote 70 Whatever we decide the exact parameters of dissent are (and I have already noted it shall not be discussed here), the power of dissent suggests that, in children’s research, while informedness and understanding may wax and wane from child to child, the requirement for voluntariness is a unifying feature of assent. In contrast, an absolute position on voluntariness and dissent is absent from discussions of children’s treatment. The same author on occasion will state expressions of dissent should be determinative while accepting that dissent to treatment might be overridden if it carries a risk of harm.Footnote 71 One small empirical study suggested practitioners’ motivation for gaining assent to treatment may be to gain the cooperation of the child and avoid litigation.Footnote 72 One may speculate that such a focus may further weaken attention to providing information and securing understanding. Thus, the force of voluntariness in assent may be weakened by attention to preventing harm and, in some cases, shifted further to preventing harm to the practitioner, perhaps at the cost of other consent-like elements.

Those who argue for assent in dementia treatment do not generally attempt to differentiate it from assent in dementia research contexts.Footnote 73 , Footnote 74In this small literature perhaps more than any other, assent lacks conceptual clarity or rigor. Sometimes assent in dementia research is implied to rest on similar grounds to consentFootnote 75; in others assent and consent are not clearly differentiated from one another.Footnote 76 In common with children’s assent, the form of consent and assent can be similar, with some authors suggesting that the person with dementia should formally sign assent documentation.Footnote 77 Partial understandingFootnote 78 and lack of objectionFootnote 79 have corollaries with the “understanding” and “voluntary” elements of consent. While being distinctive ideas, they are suggestive of a common inspiration. Nevertheless, the broad thrust of the literature is suggestive of autonomy as a broader concept. Echoing Gerald Dworkin’s influential definition of autonomy as authenticity plus independence,Footnote 80 emphasis has been placed on establishing that the assent or dissent of people with dementia expresses an “authentic” choice.Footnote 81 Authenticity may be established in two ways: through attention to past values and preferencesFootnote 82 and through ongoing social engagementFootnote 83 between researcher and participant. Engagement teaches the researcher how persons with dementia behaves when their level of well-being is high, and thus indicates their level of comfort which may otherwise not be self-evident.Footnote 84 Jan Dewing urges caution when giving attention to past values and preferences because these may devalue the status of the person with dementia in the present.Footnote 85

Despite the centrality of authenticity, it can be difficult to determine in dementia. One study noted that the conversations that people with dementia had with clinicians were skewed toward statements of agreement and approval.Footnote 86 People with dementia may be aware of their cognitive impairment and engage in face-saving behaviors that hide their lack of understanding.Footnote 87 Family members can have difficulty interpreting the wishes of close relatives with dementia,Footnote 88 while professional caregivers may ignore obvious misunderstandings to save the person with dementia embarrassment.Footnote 89 Gauging authenticity may therefore be challenging in practice. Notwithstanding Dewing’s reservations about devaluing the present person, if there are no overt objections from a person with dementia, it may be impossible to avoid an emphasis on past wishes. Under these circumstances attempts to impute the person with dementia’s competent response call to mind some aspects of substituted decision-making, which has been conceived to mean a decision based upon past wishes, presumed current wishes, and best interests.Footnote 90 Substituted decision-making has a somewhat contested relationship with autonomy,Footnote 91 a topic I will return to in due course.

Education

Assent in children’s research and treatment is argued to have a developmental, or educational, component.Footnote 92 , Footnote 93LeikinFootnote 94 argues that encouraging children to assent to treatment develops the future adults’ ability to give adequate consent. Less eruditely, one study reported that clinicians view assent to treatment as an obligation to “educate” children about the procedure they would undergo.Footnote 95 The same group of clinicians saw assent as a way to gain children’s cooperation. Information tailored toward cooperation may differ from information given for its own sake. This differs from the longer-term goals cited in discussions of assent to research. Therein it has been argued that assent teaches children that choices should be respected.Footnote 96 Potentially in variance to this, Amanda Sibley, Andrew Pollard, Raymond Fitzpatrick, and Mark SheehanFootnote 97 distinguish this perceived educational property of assent from developing a child’s autonomy. Their argument for this is that what is best for a child overall may be stripped away from the child’s right to be taught to make optimal decisions. Clearly, if teaching children to make decisions is a good in itself, it need not improve the child’s welfare to be morally valid. Nevertheless, even divorced from the child’s overall welfare, education implies a developmental (or perhaps a teleological) goal. Thus education may be about both developing future reasoning, current understanding, or engendering a particular attitude.

It is important to reflect on a more general message the emphasis on what education says about assent. Such goals allow a new perspective on the earlier question of assent and consent, since developmental goals clearly reflect the widespread view that children are “becomings.” Under this view, childhood is a stage where children prepare for adulthood, and this preparation entails a separation between the adult world and the world of children.Footnote 98 Assent for children thus could be seen as separated from consent, not because it has separate processes or purposes, but because assent is the way we demonstrate the difference between child and adult interactions with the adult world. Indeed, such an analysis is supported by the absence of an educational justification for assent in people with dementia.

Conceiving assent as a separate, child-centered standard may be viewed positively, as it allows children to assert their views as children, without a need to conform to adult norms or standards. However, this overlooks the fact that assent is itself devised from an adult perspective. Such a perspective stems from an adult view of what children are, how they think, and what they are capable of. If assent requires lower standards of understanding, different types of information, or has specific developmental aims, this firmly casts assent as a vehicle of adult expectations rather than childrens’ capabilities. Considering children’s participation in research, Rachel Balen, Eric Blyth, Helen Calabretto, Claire Fraser, Christine Horrocks, and Martin Manby note that a real danger is that adult expectations of children’s thinking and understanding may be mistaken.Footnote 99 Seeking assent may hardwire our expectations that children will warrant education, since they will have less experience, and thus make poorer decisions, than adults. Such expectations may not represent a universal truth.

Promoting Paternalistic Welfare and Preventing Harm

The conception of children’s assent in the 1977 National Commission reportFootnote 100 indicates assent initially had an explicitly paternalistic welfare function. Contemporary commentFootnote 101 indicates that the committee was impressed by the argument that assent should be part of a protective function that ensured children’s best interests were not being compromised by their involvement in research. Far from a child’s welfare being synonymous with their parents’ views, the language of the report speaks of seeking parental “permission,” rather than consent, suggesting that parents were not to be seen as exercising proxy autonomy. Rather, assent was to involve researchers and parents jointly determining a child’s welfare, on the basis that each had an independent motivation to both protect (as well as empower) the child. Some recent discussions of assent remain concerned that differences in the views of the parent and the child may lead to the child’s disempowerment.Footnote 102 If parents and the researcher/clinician share responsibility for interpreting assent, this implies a limitation of both parental and clinical authority, and offers both a right of veto. A parent and professional veto seems to confirm that sharing authority is focused on the paternalistic promotion of welfare rather than a child’s empowerment. A child cannot veto the veto: offering a dissent-based veto to a child cannot empower a child to decide her or his own welfare. Indeed, if a child’s dissent is overruled, her or his unequal standing in the decision-making process is further compounded.

Perhaps this is why paternalistic welfare promotion is rarely linked to assent outside these early discussions (albeit paternalism per se, especially as exercised by a parent in a pediatric context, is often viewed as appropriate in many cases) and respecting children’s dissent to prevent harm is much more commonly argued. As noted above, many authors argue that dissent should constitute an unambiguous veto, at least in a research context.Footnote 103 , Footnote 104The scope of dissent in treatment decisions is more fluid. It is plausible to argue that welfare benefits flow from having control over a decision.Footnote 105 If dissent may be overridden, it is less clear whether benefits flow from having a say but partial or no control over a decision. It has been suggested that the pretense of consultation in a decision may be more detrimental than no consultation at all.Footnote 106 Indeed, the insidious effects of learned helplessness have been well documented in numerous contexts.Footnote 107 While protections appear to flow from respecting dissent, respecting dissent incompletely has the potential to cause significant harms.

Emphasis on prevention of harm using dissent is repeated in the dementia literature, and here there is less equivocation about the finality of dissent. While there is some suggestion in treatment contexts that clinicians have a paternalistic welfare role that expressly limits the decision-making authority of families over relatives with dementia,Footnote 108 , Footnote 109in general, it is the case that dissent is seen to be a more powerful guide to withdrawal from research or treatment than assent is a guide to participation.Footnote 110 , Footnote 111

Critiquing the Possible Justifications for Assent

The discussion above shows a number of justifications for assent. Justifications based on what could broadly be construed as “autonomy” were found in every context (all or most elements of consent were suggested as properties of assent). Avoiding harm by respecting dissent, was found in all but dementia treatment contexts. A paternalistic welfare basis where assent was subject to the shared interpretation of clinicians/researchers was found in research with children and in treatment contexts with children and people with dementia. Justification of assent as educative was found in treatment and research contexts with children but not with people with dementia. Finally, group benefits are used to justify assent only in research with children (Table 2).

Table 2. Recurring Justifications for Assent

These findings underline questions about the ability of assent to offer a consistent approach. This is true both within specific groups when the weight given to particular justifications may cause the approach to differ and when it is used across disparate groups and circumstances. An example of the first instance is assent in children’s research. An emphasis placed on assent as autonomy places a high bar on the understanding and agency of the child who is approached in every case, while an emphasis on assent as educational instead emphasizes the essentially contingent nature of their assent, given its only basis is to teach when we can be certain the child’s decision does not matter. A greater weight given to dissent may grant the power of veto to children even if they do not understand what they are vetoing. An emphasis on paternalistic welfare may allow a researcher to veto the child’s research participation even if the child and their parents strongly disagree. Depending on the exact nature of the group benefit sought and their cost to the individual, an emphasis on group benefit potentiates considerable individual harm even if a child’s understanding is poor or they have little agency. This problem is not an absolute one—any or all of these choices may potentially be used in morally justifiable ways. Yet they may just as easily be used in ways that are not justifiable, for instance, to increase the convenience of a third party such as a family member or a practitioner (for example, by ignoring a child’s dissent because a parent insists on treatment) or to advance an interest of a researcher (for example, by accepting an assent to research where uptake is low and time is short, even though it is clear that the participant has no understanding of what she or he assents to). Such abuses may be unavoidable if they arise from misconduct. However, the threads of justification for assent are sufficiently diverse that there is also scope for a variety of good-faith understandings. While allowing enough scope for discretionary response to unique circumstances is undoubtedly a good thing, without an underlying and coherent justification for assent the range and scope of responses may be too wide. Assent may be an instance where anything goes: Indeed the rich tapestry of interpretations suggests that assent may easily articulate a spectrum of (potentially) justifiable paternalistic and unjustifiable coercive ends, since no such end will encounter a firm conceptual obstacle.

In the face of these problems, it is tempting to cut the Gordian knot and return assent to its natural limits. In the next section, I will explore the suggestion that there is a natural context and motivation for assent. In at least one of these contexts, I suggest we might at last make more of what is an increasingly attractive idea—the extension of the benefits of autonomy to those who hitherto have been denied them.

Contextually Appropriate Homes for Assent

In any reading of the assent literature, it is impossible to ignore the relationship between assent and legal standards of consent for children. Assent is held by many authors as a moral device to enhance legal provisions,Footnote 112 , Footnote 113 , Footnote 114 yet the legal rights of children to consent can and do vary from one jurisdiction to another. Priscilla AldersonFootnote 115 has identified assent with U.S. culture. Her concern is that a wholesale importation of assent from the United States to other jurisdictions, as has taken place in UK research, may distort their national approaches toward the rights of children.Footnote 116 , Footnote 117Alderson’s attention to context is instructive: Given the apparent interpretability of assent, a context-sensitive approach to background conditions may be justified.

This explicit differentiation of the ethical nature of assent from the legal context suggests that the concept of assent can be implicitly linked to a liberalization of the U.S. legal approach to children’s consent. U.S. law confers the right to consent on “mature minors”—children above a threshold age (which varies between states) who are alienated from their parents. However, while often some or all minors can independently consent to a narrow range of care and treatment,Footnote 118 where parents are not alienated from their children the parents, rather than their child, retain a right to consent to the bulk of treatment. This position is rather different from the English common law position.Footnote 119 , Footnote 120 Alderson argues this grants children of all ages significant rights to consent whatever their relationship with their parents, provided a child is judged competent to make decisions. English law in this area is, however, complex and somewhat incoherent,Footnote 121 containing as it does a peculiar situation where children can consent but not refuse, treatment. UK practitioners may already be unclear about the legal position in many situations involving children’s consent,Footnote 122 and the range of justifications for assent may sow further confusion. There appears similar potential for complications on the European mainland.Footnote 123

While bespoke tailoring of assent for particular U.S. contexts may create problems for its cogency in other areas, it does suggest a solution to the possible muddle of concepts and situations we currently find attached to assent. Assent for children seems in the U.S. context to be a candidate for doing the work we would otherwise expect of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC)Footnote 124 performs in other contexts. The UNCRC seeks to balance the best interests of the child (Article 3) and a right to participation (Article 12). Moreover, in discussing children’s welfare as “a primary” concern, the language of the convention itself was intended to allow a balance between the rights of parents and siblings (and wider society) and the rights of the child.Footnote 125 , Footnote 126 The UNCRC has not been ratified in the United States, and much of the critique inimical to children’s rights emanates from U.S. scholars.Footnote 127 , Footnote 128 , Footnote 129 , Footnote 130 The strands of autonomy, harm, paternalistic welfare, and group benefit found within many of discussions of assent seem to make similar attempts to balance the rights of parents, the rights and welfare of individual children, and the rights and welfare of children at large. Perceiving assent in this way depends on defining assent in particular ways, which may not be acceptable to all commentators. Most glaringly, it relies on a rejection of Sibley, Pollard, Fitzpatrick, and Sheehan’s contention that the aims of assent can be stripped away from the child’s best interests.Footnote 131 Yet, potentially, this claim is influenced by local culture, emanating as it does from an English institution where the different legal standing of children will affect the types of justification that are offered for assent.

If this analysis is correct, then a cogent way to view children’s assent might be as a specific doctrine that answers some dilemmas about children’s rights in the United States. Seeking assent may therefore be justified in treatment and research decisions in the United States, while being an imperfect fit for the problems of treating and doing research with children elsewhere. In other jurisdictions, children will suffer their own distinctive constellations of inattention, abuse, and oppression that may be better addressed in other ways. This draws into question the need for assent in contexts where the UNCRC has been more influential on the law. This is certainly the case in English Law where the Children Act 1989 gives effect to many of the provisions of the UNCRC. Although the situation is not perfect,Footnote 132 the UNCRC is increasingly affecting policy-making throughout the UK.Footnote 133

This analysis of assent in children sees assent as a parochial concept and raises questions about whether assent is fit for other populations. This seems a contentious end for assent. Many find assent an intuitively attractive way to advance liberalism in healthcare, perhaps because it seems to offer the prospect of extending the autonomy of individuals in marginalized and overlooked populations. Although the context of dementia is different, it may ultimately guide us to a place for assent more in keeping with this liberating agenda. There is a developing international approach to the problems of the binary approach to incapacity. The emphasis on judging the authenticity of the assent of a person with dementia raises questions about the place and validity of a substituted decision-making approach. Such approaches have been defended, largely due to the relative unacceptability of alternatives.Footnote 134 , Footnote 135Despite such pragmatic arguments, substituted decision-making faces a mounting critique, having been roundly condemned by the U.N. Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) because of their potential to thwart the rights and actual preferences of people with disabilities.Footnote 136 The tendencies to disvalue the current experience of a disabled person over their past preference, to perceive we know a person better than we actually may,Footnote 137 or to over-extrapolate from distant events, have been argued to make substituted decisions speculative and their truth-value theoretically problematic.Footnote 138 The CRPD claims the better alternative is supported decision-making, where a person who has difficulties in understanding, making, or communicating a decision is given adequate help and resources to overcome these difficulties. A commitment to supported decision-making raises a host of questions, including how it should apply to those people whose level of decision-making ability is extremely low. Supported decision-making approaches are under-researched and far from being fully operationalized.Footnote 139 Yet it is impossible to ignore the potential for assent to complement such an approach in treatment and research decisions. Perhaps then, attempts to spread the solicitation of assent in dementia research and practice should find common causes with the quest to develop robust solutions to supported decision-making. Indeed, a more radical claim, prompted by the connection assent highlights between children and incapacitated adults, is that both children and adults should benefit equally from the move away from blanket judgments of capacity and incapacity to receive similar attention to their liberty and welfare. This could build on the potential of supported decision-making to enhance autonomy, offering support based on need, irrespective of whether a person is a child, has dementia, or is an otherwise competent adult struggling with a particular decision.

Assent should be regarded as part of a global movement that, however imperfectly, has taken faltering steps toward these possibilities; indeed, recent attempts to apply assent to the treatment of animals are likely to strengthen this analysis. That these steps have resulted in an unfinished and potentially inconsistent concept highlights the urgent need to develop coherent theoretical foundations to meet the shared dilemmas we encounter when we dissolve the walls between capacity and incapacity. Such an accomplishment may allow assent to fulfill its intuitive promise.

Conclusion

As a mechanism to include children in research, assent has entered law, research, and treatment contexts. Yet it remains conceptually hollow. My analysis suggests five justifications of assent that may struggle to promote a coherent and consistent approach in all instances assent is invoked. Taking my analysis further, I have argued assent may need to attend to the background conditions in specific contexts in which it is used, and discussed two contexts where I believe assent might be usefully deployed. Of these, I suggest the most worthy project is to tie assent to the growing international movement attempting to address the lacunae that are created by binary approaches to decision-making. The intuitive appeal of assent to many lies in its apparent potential to address this area. Since assent currently lacks firm theoretical foundations to underpin a stable and consistent usage in practice, it is to these theoretical foundations of assent that future research should be addressed.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Holly Kantin and Hope Ferdowsian, Paul Baines, and members of the BABEL team for their valuable comments on earlier drafts of this article. Naturally, I remain responsible for any errors or omissions herein.

Funding Statement

This research was funded in whole, or in part, by the Wellcome Trust Grant No. 209841/Z/17/Z. For the purpose of Open Access, the authors have applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.