Global governance gaps emerge where regulation is missing due to the fragmentation of production and trade across global supply chains (Crane, LeBaron, Allain, & Behbahani, Reference Crane, LeBaron, Allain and Behbahani2019; Donaghey, Reinecke, Niforou, & Lawson, Reference Donaghey, Reinecke, Niforou and Lawson2014). What has been less recognised is the problem of global representation gaps (Towers, Reference Towers1997), where constituents, communities and workers affected by global business activity lack effective representation in global governance. Instead, various unelected actors “self-appoint” as representatives (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012) in myriad and partly overlapping private governance regimes to protect human and worker rights (Fransen, Reference Fransen2012). These self-appointed representatives, including campaign groups and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), participate in transnational rule making on behalf of citizens, consumers, local communities, workers and others in largely unregulated global supply chains but lack an explicit mandate to represent. Nevertheless, they are often highly effective in bringing issues of labour and human rights abuses to the agendas of Western consumers and corporations. As a result, global governance—rule making and power exercise at a global scale—is increasingly shaped by entities that are not authorised by affected constituents to act but instead derive rule-making power from market and consumer demand, raising the question of whether and when their input to global governance can be legitimate.

While scholars have developed deliberative criteria to assess the input legitimacy of private governance schemes (Gilbert & Rasche, Reference Gilbert and Rasche2007; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Schormair & Gilbert, Reference Schormair and Gilbert2021), the question of who can legitimately represent stakeholder interests has remained underdeveloped. Yet, representation is a central institution in democratic practice, and the question of transnational representation deserves more attention (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012; Severs, Reference Severs2012). Thus how should we theorise and normatively assess the processes of representation at the transnational level? While electoral authorisation and accountability are typically required for democratic representation and input legitimacy (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1997), economic activity across national borders challenges established, territorially based democratic representation (Disch, Reference Disch2011). As a result, the practice of representation is undergoing significant transformation (Bohman, Reference Bohman, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). Representation is increasingly contingent on the ability of transnational constituencies to form across borders around certain issues or economic relations, such as supply chains. Yet, the ideal of democratic legitimacy is rarely achieved in fragmented supply chain contexts.

In this article, we study the politics of transnational representation in private labour governance. We examine how the interaction of different regimes shapes the representation of worker interests in global supply chains. To do this, we focus on the role of self-appointed labour rights NGOs in providing “representative claims” and the role of unions in providing “representative structures.” As will be developed, neither provides an optimal form of democratic representation in global supply chains. Thus we seek to understand how different and less than perfect representation regimes interact and under what conditions complementarities emerge that can improve democratic practice beyond seeking “optimal design” (Bohman, Reference Bohman, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 73). We draw on a longitudinal study focussing on the interaction of unions and NGOs in representing labour interests in the Bangladesh Accord for Fire and Building Safety (the Accord). The Accord was initiated following the 2013 Rana Plaza disaster to ensure factory safety in the Bangladesh ready-made garment sector. We do not argue the Accord as the perfect reflection of the “authentic” preferences of Bangladeshi workers but focus on the specific issue of the representation of worker interests in the area of workplace safety.

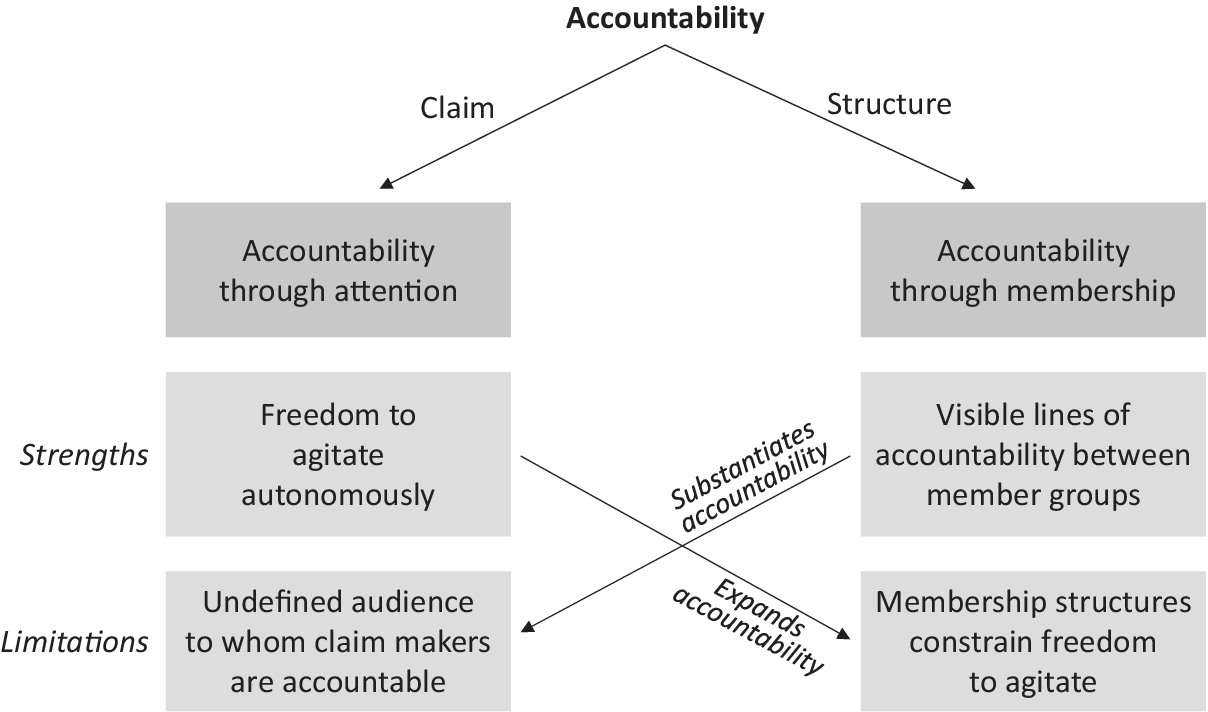

To understand how the interests of Bangladeshi garment workers were represented, and when and how representative claims and structures became complementary or conflicting, we derive normative principles from political theory that allow us to examine empirically the interaction of NGOs and unions along three dimensions of democratic representation: 1) creating presence for, 2) authorisation by, and 3) accountability to affected constituents. On this basis, we develop a framework of transnational representation that conceptualises the underlying logics that explain when representative claims and structures can become complementary: representative claims generate legitimacy to represent workers in the public sphere through generating attention to claims, whereas representative structures generate legitimacy in the sphere of the employment relationship through membership. In successful representative alliances, the former can expand the representation of workers where membership coverage is weak, while the latter can substantiate representation where attention-based claims alone would be precarious. Nevertheless, whose interests get represented and how is also the outcome of the politics of input legitimacy. Thus, we argue that transnational representation creates “second-best institutions” like the Bangladesh Accord, namely “those that take into account context-specific market and government failures that cannot be removed in short order” (Rodrik, Reference Rodrik2008: 100). Our work contributes to, first, a more nuanced understanding of input legitimacy and democratic representation in transnational governance and, second, to the literature on complementarities between different actors in collaborative governance, with a particular focus on NGO–union relationships.

DEMOCRATIC REPRESENTATION AND TRANSNATIONAL PRACTICE

Input Legitimacy and Representation in Democratic Theory

A key principle for the political legitimacy of rule making is that of input legitimacy—the idea that “political choices should be derived, directly or indirectly, from the authentic preferences of citizens” (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1997: 19).Footnote 1 For Scharpf (Reference Scharpf2003), input legitimacy means “government by the people” and realising the aim of democracy as “collective self-determination.” In nearly all Western-style liberal democracies, input legitimacy is typically achieved through creating democratic representation of constituencies by means of some form of electoral democracy (e.g., Benhabib, Reference Benhabib1996) or through individuals voluntarily joining interest associations (Streeck & Schmitter, Reference Streeck and Schmitter1985). Representation can be defined as the “process in which one individual or group (the representative) acts on behalf of other individuals or groups (the represented) in making or influencing authoritative decisions, politics, or laws of a polity” (Thompson, Reference Thompson, Smelser and Baltes2001: 11696).

The creation of political presence of a constituency is a foundational condition for representation. As Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967: 9) stressed, representation is about “making present what is absent.” This casts representation as “a surrogate form of participation for citizens who are physically absent” in formal democratic processes due to constraints of complexity and scale (Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008: 393). Political presence must be actively created by acts of representation—by making present the represented by speaking for, acting on behalf of or in the interest of, or standing in for them. In the so-called standard account of democratic representation (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967), the defining institutional criteria that render this process legitimate are authorisation (i.e., through elections) by a constituency and accountability to that constituency: representatives are formally authorised to speak, act and make decisions on behalf of constituents, and constituents have mechanisms through which representatives can be held accountable. This conveys legitimacy to the rules generated and to their enforcement.

Representative democratic politics have largely been conceptualised as territorially based electoral representation at the level of the nation-state. However, the globalised context challenges this conception of democracy (Bohman, Reference Bohman, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012; Scherer, Palazzo, & Baumann, Reference Scherer, Palazzo and Baumann2006) and thus the notion of input legitimacy through ordinary political representation. Complex supply chains allow multinational corporations to shift locations to avoid effective regulation, including the institutions of representation (Bognanno, Keane, & Yang, Reference Bognanno, Keane and Yang2005). Even though political scientists continue to insist that “it is only through representation that a people comes to be as a political agent, one capable of putting forward a demand” (Disch, Reference Disch2011: 102), the standard account of representation, based on a pre-existing constituency—members of a political community—seems poorly suited to deal with global social, environmental and human rights challenges that are unconstrained by nation-state borders. An emerging literature has therefore started to question the assumption that democratic representation needs to “have its origins in a [territorially defined] constituency” (Disch, Reference Disch2011: 130). Transnational constituencies and their preferences can no longer be conceptualised as pre-existing and predefined, such as through territorial boundaries. This draws attention to the processes of representation through which constituencies are formed across national borders and around transnational issues, causes or economic relations.

Input Legitimacy in Private Transnational Governance

The question of how constituencies are formed and democratically represented across national borders is central to transnational governance, defined as governance beyond the boundaries of the nation-state. Unlike nation-state regulation, transnational private governance arrangements are typically not formally authorised by those affected to govern a certain issue (Schouten, Leroy, & Glasbergen, Reference Schouten, Leroy and Glasbergen2012). The related challenge concerns “the lack of congruence between those who are being governed and those to whom the governing bodies are accountable” (Risse, Reference Risse, Benz and Papadopolous2006: 180). This raises the question of whether and how transnational governance can be democratic.

There is general agreement that democracy depends on stakeholder participation to generate input legitimacy (de Bakker, Rasche, & Ponte, Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019). Within the business ethics literature, the focus has largely been on the discursive quality of the governance and rule-making process (Arenas, Albareda, & Goodman, Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Gilbert & Rasche, Reference Gilbert and Rasche2007; Habermas, Reference Habermas1998), discursive justification (Schormair & Gilbert, Reference Schormair and Gilbert2021), or the deliberative capacity of participants (Soundararajan, Brown, & Wicks, Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019). Mena and Palazzo (Reference Mena and Palazzo2012) reinterpret Fritz Scharpf’s (Reference Scharpf1997) notions of input- and output-oriented legitimacy to establish criteria for multi-stakeholder governance schemes. They identify inclusion, procedural fairness, consensual orientation and transparency as criteria for input legitimacy and rule coverage, efficacy and enforcement as criteria for output legitimacy. It is important to note, though, that this reinterpretation deviates from Scharpf (Reference Scharpf1997, Reference Scharpf2003), who emphasised “electoral accountability as a crucial input-oriented mechanism for keeping governors oriented toward the common interest of their constituencies” as part of a territorially based approach to evaluating representation in the European Union. Mena and Palazzo (Reference Mena and Palazzo2012: 550) acknowledge that their model focuses more on the how rather than the who of participation, as it “does not consider legitimacy challenges at the level of individual actors” who participate in multi-stakeholder initiatives. Thus, while the input-oriented criteria of inclusion and procedural fairness focus on the involvement of affected stakeholder representatives and their ability to influence decision-making processes, the question of who can and should act as a representative of affected stakeholders is left unaddressed.

The question of who represents is central to ensuring that governance is “derived, directly or indirectly, from the authentic preferences of citizens” (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1997: 19). While transnational governance regimes typically seek to generate input legitimacy by including “representatives” of affected stakeholders in decision-making, in practice, they often only pay lip service to the “all affected interests’ principle” (Goodin, Reference Goodin2007), as those potentially affected by a collective decision do not always have the opportunity and capacity to influence that decision. Often transnational governance includes what Montanaro (Reference Montanaro2012) calls “self-appointed representatives,” such as NGOs and activist groups in the Global North, rather than representatives who are mandated by the beneficiaries themselves, such as workers.

By operating without the authorisation and accountability typically thought to be central to democratic representation (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008), there is the risk that self-appointed representatives engage in symbolic politics that satisfy their constituencies while remaining “unresponsive to the real needs of the people whom they claim to serve” (Keohane, Reference Keohane, Held and Koenig-Archibuigi2003). Even well-meaning NGOs and activists risk generating policy instruments that deviate significantly from those preferred by their intended beneficiaries (Koenig-Archibugi & MacDonald, Reference Koenig-Archibugi and MacDonald2013). Some scholars have gone as far as to argue that NGOs that claim to speak in the name of marginalised populations can end up undermining their agency on the ground (Siddiqi, Reference Siddiqi2020). Also, in accounts to date of transnational labour analysis, with a few exceptions (Bartley & Egels-Zandén, Reference Bartley and Egels-Zandén2016; Egels-Zandén & Hyllman, Reference Egels-Zandén and Hyllman2006; Zajak, Reference Zajak2017), there has been a tendency to conflate different representative actors under the broad heading of “civil society.” For example, trade unions are typically collapsed into “cause-based” organisations like other civil society organisations, even if they are based on a fundamentally different logic of how constituencies are formed and represented. Thus there is need for conceptual clarity and delimitation of the different actors offering representation and their underlying logic to understand the input legitimacy of transnational labour governance. In the next section, we explore theoretically two differing approaches to the democratic representation of worker interests.

DEMOCRATIC REPRESENTATION IN LABOUR GOVERNANCE

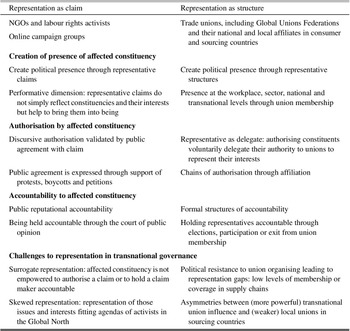

The question of who (beyond the state) can and should represent affected constituencies depends on the intellectual tradition from which the question is considered. Within the deliberative tradition in democratic theory, a discursive view of representation as claim making has emerged. This contrasts with the more traditional approach to representation as structure, which underpins the industrial democracy tradition in our case of worker representation. The approaches proceed from different normative assumptions as to how democratically legitimate representation is established. Here we compare and contrast these assumptions based on the criteria of political representation presented earlier. We focus on, first, the ability of a representative to give political presence to those whose interests are affected (“affected interests standard”) second, whether the affected are empowered to authorise and, third, to hold accountable a representative. Table 1 summarises their main features.

Table 1: Key Dimensions of Representation as Claim and Structure in Global Labour Governance

Representation as Claim

To address the limitations of building global-level representation, some political theorists have advocated a “deliberative turn” in democratic theory, focussing on the role of discourse and communication (Dryzek & Niemeyer, Reference Dryzek and Niemeyer2008; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2011). Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2000: 84) provocatively suggested the need to “step back and ask whether democracy does indeed require counting heads.” The notion of “discursive representation” suggests that transnational actors represent, not real people, but discourses (Dryzek & Niemeyer, Reference Dryzek and Niemeyer2008). Taking this argument forward, Saward (Reference Saward2010) proposed that representation may be best understood as the making of a “representative claim.”Footnote 2 Proponents argue that representative claims play an important role in a global context, especially “where electoral constituencies fail to coincide with those affected by collective decisions” (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012: 1094; see also Bohman, Reference Bohman, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). By expanding “the range of democratically relevant voices” where they may otherwise be excluded, representative claims can raise consciousness, identify latent injustices, or provoke a discursive process (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012: 1099). Democratic legitimacy is argued to be generated discursively, rather than through electoral politics.

Creating Political Presence of an Affected Constituency

The first dimension is how representative claim makers bring affected constituents—here workers—and their interests into the political process. Broadly speaking, and in line with a constructivist interpretation of Pitkin’s (Reference Pitkin1967; see Disch, Reference Disch2011, Reference Disch2012) foundational definition, to represent means, literally, to make people’s voices, opinions, and perspectives “present” in governance processes. But rather than making “present” through “mirroring” or “reflecting” an already existing constituency, proponents of discursive representation go one step further in suggesting that constituencies are themselves constituted through the process of representation. This approach conceptualises representation as performative: “acts of representation do not simply reflect constituencies and their interests but help to bring them into being” (Disch, Reference Disch2012: 600). This breaks with the traditional idea of representation as an aggregation of interests through a “delegate” acting in the name of the represented. Thus “self-appointed representatives bring constituencies into being” (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012: 1100) that would not otherwise have political presence in traditional political spaces, including marginalised people or future generations.

Representative claims create presence mainly in the (global) public sphere—a domain of social life where public opinion can be formed through deliberation (Habermas, Reference Habermas1989). They are typically made by public interest groups that claim to be acting for a common good, such as NGOs, and form part of “global civil society” (Kaldor, Reference Kaldor2003). They engage in public campaigning to disseminate their claims in the public sphere and bring certain groups, such as workers, as affected constituencies into being in transnational governance processes. This acts as a “discursive interface” between international organisations and global citizens (Nanz & Steffek, Reference Nanz and Steffek2004). Claim making can thus contribute to the democratic process, because “without this intervention there would be no incorporation of those marginal sectors into the public sphere” (Laclau, Reference Laclau2005: 116).

Authorisation by an Affected Constituency

For the creation of political presence to be democratically legitimate, representatives need to be authorised by affected constituents. However, because there is no pre-existing authorising constituency, authorisation poses an obvious conceptual difficulty (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012). Representative claim makers rely on “discursive authorization” (Dryzek & Niemeyer, Reference Dryzek and Niemeyer2008) in the form of public agreement. Public agreement is expressed through support of protests, boycotts, letter writing and petitions, which contributes to a self-appointed representative’s public profile. Legitimate claims differ from those that are merely successful in that they are perceived as legitimate “by appropriate constituencies under reasonable conditions of judgment” (Saward, Reference Saward2010: 144). This denies the political theorists the role of adjudicator of legitimacy and instead leaves it to the appropriate constituency to accept or reject authorisation.

Accountability to an Affected Constituency

In the absence of a clearly defined authorising constituency who could hold representatives accountable, self-appointed representatives must subject themselves to discourse-based mechanisms of accountability, such as public reputation (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012) or what Mansbridge (Reference Mansbridge2009) calls “deliberative accountability.” Here representatives seek accountability through public reasoning and discursive justification (Schormair & Gilbert, Reference Schormair and Gilbert2021). Ideally, they engage “in two-way communication with constituents, particularly when deviating from the constituents’ preferences” (Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2009: 370). Self-appointed representatives establish a reputation for certain positions and may be held accountable through the court of public opinion through what Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1970: 30) terms exit and voice. Exit involves removing oneself from mailing lists, cancelling donations or ceasing participation in programmes. Voice involves publicly denouncing representative claims made on someone’s behalf as false, skewed or otherwise objectionable.

Challenges to Representative Claims in Transnational Governance

Proponents concede that representative claims “can work democratically and undemocratically” (Saward, Reference Saward2010: 1; Disch, Reference Disch2011). Reliance on discursive sources of authorisation and accountability means that there can be confusion or ambiguity with regard to who acts as the authorising constituency, who can hold representatives accountable, or maybe even who counts as being affected. This may result in “unequal representation of stakeholder concerns in deliberative processes” (Nanz & Steffek, Reference Nanz and Steffek2004). Montanaro (Reference Montanaro2012: 1105) speaks of “surrogate representation” when an affected constituency is not empowered to authorise or hold claim makers accountable and of “skewed representation” when political presence is disproportionately skewed toward certain constituencies, such as business interests or the agendas of activists in the Global North (Siddiqi, Reference Siddiqi2009; Tanjeem, Reference Tanjeem2017). Moreover, “presence” is often created in the Global North in ways that operate within the logic and power asymmetries of supply chain capitalism: because public agreement, reputation and resources typically come from Western donors, audiences and consumers, issues that matter to northern activists and consumers can then overshadow and displace local concerns. In sum, representative claims can provide a powerful source of transnational representation, but also risk being skewed towards the agendas of claim makers.

Industrial Democracy and Representation as Structure

Industrial democracy, originating in industrial relations scholarship and constituting the intellectual foundation of trade unionism, departs from fundamentally different assumptions about the representation of workers’ interests. Industrial democracy, as put forward by British social reformers the Webbs (Webb & Webb, Reference Webb and Webb1897), applies the principle of democratic representation to the workplace. It conceptualises representation in terms of representative structures. The most established system of representative structures is self-governing trade unions: unions provide a structural mechanism through which workers, independent of their employers, elect and authorise representatives, provide mandates and hold the unions accountable. Trade unions thus are seen as playing a key role in democratising workplace relations but are also democracies in their own right: “that is to say their internal constitutions are all based on the principle ‘government of the people by the people for the people’ ” (Webb & Webb, Reference Webb and Webb1897: vi). Industrial democracy stresses the importance of who participates. Emphasis is placed on workers having a democratic input into decision-making in the industrial process and hence their workplace (Wilkinson, Dundon, Donaghey, & Freeman, Reference Wilkinson, Dundon, Donaghey, Freeman, Wilkinson, Donaghey, Dundon and Freeman2014). Those affected should be directly involved—through membership in collective interest-based associations—in processes of decision-making which affect their everyday working lives (Fung & Wright, Reference Fung and Wright2001). This is in line with Scharpf’s (Reference Scharpf1997: 19) democratic ideal of input legitimacy, where “political choices should be derived, directly or indirectly, from the authentic preferences of citizens,” here the worker-citizens of the firm. The right of workers to be part of determining and defining their interests offers more equitable means of resolving underlying conflicts of interest that characterise the employment relationship (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2012).

Creating Political Presence of an Affected Constituency

Trade unions ground their democratic legitimacy to represent members in representative membership structures. Ideally, high levels of membership or coverage in any given sector create a strong political presence of workers. They also allow workers to participate directly in the representative process. The employment relationship defines a union’s sphere of operation and where political presence is created: a union’s representative approach and capacity are inherently linked to an exchange of labour between workers and employers. The relationship is not based around particular issues but is an ongoing relationship which covers the entirety of this exchange, including pay levels, hours of work and even the continuing nature of the relationship. While the main focus of this relationship is the workplace, where trade unions create the political presence of workers through negotiating with employers or employer groups, unions engage at multiple levels, including the sector, national and transnational levels, such as the International Labour Organization (ILO), to influence the regulation of employment (Kaine, Reference Kaine, Wilkinson, Donaghey, Dundon and Freeman2020).

Authorisation by an Affected Constituency

In joining a union, workers formally authorise the union to represent them in negotiations and collective bargaining with employers. Thus a union’s authorising constituency is clearly defined by the boundaries of union membership. Authorisation therefore builds on a model of representative as delegate: constituents voluntarily delegate their authority for the aggregation and pool their individual interests through collective bodies with elected representatives. This enables representatives to make decisions based on their judgement of the interests of the constituents. Membership is assumed to ensure explicit consent from members. Authorisation also occurs through participation: union meetings or locally elected committees provide their members with local democracy (Martin, Reference Martin1968). Union members can feed into and vote on policies which mandate the local leadership over issues such as industrial action and, thus, bring features of participatory democracy to union representation. Global chains of authorisation emerge where branches form federations, and federations become part of national and transnational structures in the form of global union federations (GUFs).

Accountability to an Affected Constituency

Explicit authorisation of representatives by the represented also has important implications for relations of accountability. Unions are primarily accountable to those who authorise them to represent: their members. Union members should be able to hold their union officers accountable for their performance through (re-)elections, through (the threat of) exit from union membership, or through participation in branch meetings and direct exchange with their elected union officials (Martin, Reference Martin1968). The boundaries of accountability are thus set by the boundaries of membership. Moreover, unions have an important stake in the employment relationship and therefore the economic sustainability of the business or sector (Budd, Reference Budd2004). This reality makes them legitimate participants in negotiations with employers because their members will suffer the consequences of demands that threaten the viability of the enterprise and, hence, the employment relationship (Budd, Reference Budd2004).

Challenges to Industrial Democracy in Transnational Governance

There is no doubt that unions were (and often still are) highly contested and resisted in many Western economies. Establishing meaningful industrial democracy has been even more challenged by the increasingly globalised nature of production. While unions have representative membership structures, they often lack actual members in workplaces, which undermines their legitimacy to represent workers. This is not least because many countries, especially those which compete for a share of the global market through low costs, actively supress the development of well-functioning unions and workplace democracy (Anner, Reference Anner2015). Freedom of association—the right of workers to organise to pursue their collective interests—is often flouted despite being a human rights hyper-norm (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2012). The International Trade Union Confederation (2021) highlighted that 87 per cent of countries violate the right to strike, while 79 per cent of countries restrict the right of workers to join unions and to collective bargaining. The effect is that worker representation through unions has been aggressively eroded with a “representation gap” developing (Towers, Reference Towers1997).

Such representation gaps have led to unions increasing their international solidarity work in attempts to reduce these gaps in the spirit of Marx’s call for workers of the world to unite (Hyman, Reference Hyman2005). Such efforts, though, have been contested by some. For instance, Rahman and Langford (Reference Rahman and Langford2014) describe the AFL–CIO solidarity work in Bangladesh as “hegemonic trade union imperialism” that aims at controlling and shaping unionism in line with the foreign policy goals of the US imperialist nation-state. In sum, representative structures provide substantive forms of representation, but the obstacles to developing workplace representation mean that the extent to which such representation is strongly rooted through global supply chains may be limited.

Complementarity of Representative Approaches in Global Labour Governance

Much research on transnational labour governance has tended to focus on the role of either unions and industrial relations or civil society actors and corporate social responsibility (CSR) (cf. Preuss, Haunschild, & Matten, Reference Preuss, Haunschild and Matten2009). A small, but growing scholarship has started to focus on the interaction between unions and NGOs. The main focus has been on how complementarity between unions and NGOs can increase their joint effectiveness to protect worker rights (Egels-Zandén & Hyllman, Reference Egels-Zandén and Hyllman2006)—hence output legitimacy. The general consensus is that by combining strategic capacities, NGOs and unions can mobilise joint pressure on brands or retailers to intervene in support of workers’ demands, while conflictual union–NGO relationships undermine mobilisation (Bartley & Egels-Zandén, Reference Bartley and Egels-Zandén2016; Egels-Zandén & Hyllman, Reference Egels-Zandén and Hyllman2006). For instance, NGOs and unions called upon complementary power resources to create the Bangladesh Accord (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2015). But we know much less about how union–NGO alliances affect input legitimacy. While scholars have begun to recognise differences in identity construction, governance systems, and resources (Egels-Zandén & Hyllman, Reference Egels-Zandén and Hyllman2011), the differences in representative approaches and how they affect the democratic quality of governance have received little attention.

Owing to the aforementioned challenges, no one approach or actor can provide ideal forms of worker representation—in fact, the very design of global supply chains is such that they actively reduce the quality of worker representation. Achieving perfect representation thus becomes structurally impossible, as corporations use liberalised markets to seek out systems where labour representation is weak (Robinson & Rainbird, Reference Robinson and Rainbird2013). In the face of these constraints, scholars have stressed the need for identifying constructive approaches “for improving democratic practice without looking for some optimal design or blueprint” (Bohman, Reference Bohman, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 73). Thus we seek to understand whether and when approaches may become complementary in strengthening democratic representation. We ask how do representative structures and representative claims interact in transnational labour governance processes? How might they become complementary (or clashing) in the democratic representation of worker interests?

METHODS

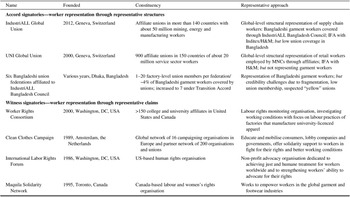

Our research insights emerged from an abductive research design (Timmermans & Tavory, Reference Timmermans and Tavory2012) that was informed by our interest in understanding the interplay of unions and NGOs in transnational labour governance. We identified the Accord as a “complementary regime” of labour governance (cf. Donaghey et al., Reference Donaghey, Reinecke, Niforou and Lawson2014; Huber & Schormair, Reference Huber and Schormair2021; Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2015), where NGOs and unions collaborated to represent labour vis-à-vis capital. Our aim is not to represent the voice of the Bangladeshi garment worker, which others have done (Alamgir & Banerjee, Reference Alamgir and Banerjee2019; Kabeer, Huq, & Sulaiman, Reference Kabeer, Huq and Sulaiman2020; Siddiqi, Reference Siddiqi2020). Instead, our aim is to understand how the interests of Bangladeshi garment workers have been represented in the transnational governance process. Our level of analysis is thus the “labour caucus”—those signatory unions and NGOs that acted as official representatives of workers and their interests in the Accord.

This article draws on a seven-year research project, which went through multiple rounds of data collection. We started interviews in 2013, shortly after the Accord was negotiated, to understand its emergence (eight trade unions, four NGOs, six Accord signatory companies, one ethical trading initiative, four ILO staff and two Accord staff, for a total of twenty-five interviews). The author team then jointly conducted interviews at regular intervals, with six intense fieldwork periods in Bangladesh between 2014 and 2019. In this phase, we focussed on the role of trade unions and NGOs in implementing the Accord and on interviewing Bangladesh trade unionists (n = 17), GUF/international trade unionists (n = 12), NGOs (n = 5), and Accord staff (n = 11). To understand the wider context, we also interviewed ILO staff (n = 5), Accord signatory companies at headquarter (n = 8) and at Bangladesh office level (n = 14), factory managers (four individual and fourteen in-group interviews), three local labour experts, and representatives from the industry association Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (n = 7), totalling 110 interviews lasting 30–180 minutes. In addition, we met with and interviewed groups of workers in the factories we visited with help of a translator, including meeting workers offsite in the more trusted environment of union offices. In supplementary materials published online, Appendix A provides an anonymised and detailed overview of our fieldwork, and Appendix B provides an example of one of our semi-structured interview schedules.

As is common in qualitative research, our analysis started during the fieldwork. During our fieldwork trip to Bangladesh, we discussed our observations and wrote analytical memos about emergent themes. As our interest was in “how” workers were represented in the creation and implementation of the Accord and by “whom,” we focussed on the role of the different actors which represented workers: unions versus NGOs. Early on, it became clear that both played highly complementary roles in the Accord but also clashed on numerous occasions.

Differences in opinion within the author team regarding the roles of unions and NGOs led to discussions that prompted us to articulate and clarify different approaches to representation. Thus, after a first, open round of descriptive coding to develop a systematic understanding of our data, we engaged in a second, more targeted round in which we coded for the roles of unions and NGOs, their respective contributions to the Accord, and their interactions, thereby carefully comparing self-descriptions with external assessments. This revealed distinctive logics—which we later labelled attention versus membership—that underpinned NGOs’ versus unions’ legitimacy to represent.

Next, to refine our understanding further, we engaged with the literature on democratic governance from an interdisciplinary perspective, drawing on political theory, CSR and industrial relations. From this, we identified two approaches to representation—as structure and as claim, which we associated with unions and NGOs, respectively. We then used established criteria of democratic representation—presence, authorisation, and accountability (Montanaro, Reference Montanaro2012; Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008)—to guide our abductive analysis of representation by unions and NGOs. By comparing theoretical resources with empirical insights, we analysed the interplay of claims and structures, focussing on what led to complementarities versus clashes. In this final round of selective coding, we focussed on the conditions that could explain when and why the interplay of representative approaches can enhance transnational representation. We therefore coded for how different logics of representation affected the three dimensions of democratic representation. Figure 1 presents our final data structure. Our findings section provides power quotes from our interviews; Appendix C, published with supplementary materials online, provides examples of confirmatory quotes which support our analysis.

Figure 1: Data Structure

Research Setting: The Bangladesh Accord for Fire and Building Safety

Without doubt, the environment for worker representation in Bangladesh is a difficult one. Bangladesh is a prime example of what Anner (Reference Anner2015) calls “despotic market labor control,” where workers lack both labour market power and the power to demand effective state protection as citizens through electoral democracy. The Bangladeshi government and garment industry are active in suppressing any type of worker representation that could threaten the low-cost production model that generates over 80 per cent of the country’s total exports. As part of this, the Bangladeshi government has established export processing zones, which place extreme curbs on freedom of association (International Labour Organization [ILO], 2020). Similarly, the country established an Industrial Police, who are charged with ensuring that the manufacturing sector is unhindered by labour protest. Numerous authors report violence against and/or killings of workers through both state mechanisms and employer sponsorship (Donaghey & Reinecke, Reference Donaghey and Reinecke2018; Khanna, Reference Khanna2011). Human Rights Watch (2015) describes the “chilling” effect on union organising in Bangladesh, including “physical assaults on union organizers by both managers and thugs (‘mastans’) acting at their behest, threats and multiple forms of harassment, and dismissal of union members.”

Following decades of suppression, the position of unions is fragile due to union fragmentation (involving more than thirty union federations in the garment sector alone, based on the enterprise unionism model; see Zajak, Reference Zajak2017), low density (4 per cent union membership at the time of Rana Plaza; ILO, 2015), an immature system of industrial relations, and political suppression. Pressure by the ILO and Bangladesh’s most important trading partners to encourage union formation led to an optimistic but short-lived period of union growth post Rana Plaza, before facing renewed government-led suppression (Donaghey & Reinecke, Reference Donaghey and Reinecke2018). In addition, issues are consistently raised about external interference in Bangladeshi unions, including union affiliation with political parties; dependence on donors from wealthier economies rather than on members; and so-called yellow unions, which are established by employers to further their interests rather than those of workers (Rahman & Langford, Reference Rahman and Langford2014; Siddiqi, Reference Siddiqi2020). Thus garment workers were in a very disadvantageous position to represent their own interests vis-à-vis local employers and policy makers through collective organising, let alone confronting global buyers whose prime motives to source from Bangladesh were its low production and labour costs (minimum wage currently set at US$95 a month). Instead, transnational labour rights NGOs, such as the Worker Rights Consortium and the Clean Clothes Campaign, have become in consumer economies a powerful voice to highlight labour abuses.

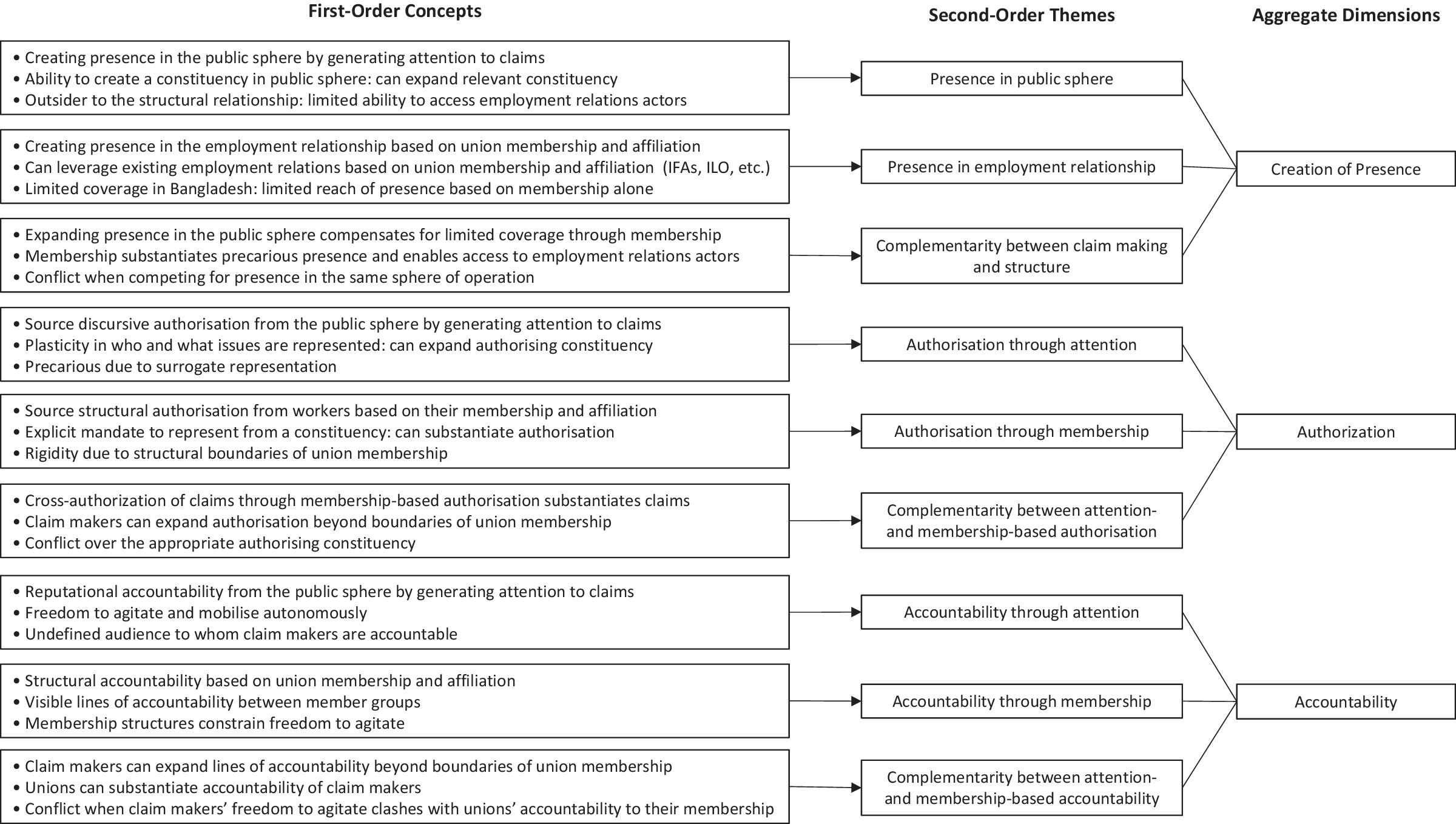

In the aftermath of the 2013 Rana Plaza tragedy, which killed more than eleven hundred workers, GUFs and labour NGOs leveraged global public pressure to force apparel brands and retailers sourcing from Bangladesh into an unprecedented collective and legally binding agreement to reform worker safety: the Bangladesh Accord for Fire and Building Safety (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2015; Schuessler, Frenkel, & Wright, Reference Schuessler, Frenkel and Wright2019). Coming into existence in May 2013 and being extended until May 2021, it grew to more than two hundred corporate signatories covering more than sixteen hundred supplier factories. As a union–company agreement, the Accord provided equal representation of corporate and labour interests. As presented in Table 2, labour was represented by all six local Bangladeshi union federations affiliated with the IndustriALL Bangladesh Council and two GUFs, IndustriALL and UNI Global (representing manufacturing and retail workers, respectively). Four labour rights NGOs were witness signatories. The ILO acted as neutral chair. In addition to safety monitoring and remediation by independent inspectors, a core pillar of the Accord was the aim to strengthen the representation of workers in factories on the ground by giving them an explicit role in monitoring factory safety. This included creating worker safety committees, founding a complaints mechanism, establishing workers’ right to refuse unsafe work, and including worker representatives on inspection visits (see Donaghey & Reinecke, Reference Donaghey and Reinecke2018; Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021).

Table 2: Worker Representation as Structure and Claim in the Accord’s Labour Caucus

Note. IFA = International Framework Agreement. MNC = multinational corporation. Table has been adapted from Reinecke and Donaghey (Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2015).

FINDINGS

Our findings examine the interaction between representative claims made by labour rights NGOs and unions’ representative structures in establishing and implementing the Bangladesh Accord along the three dimensions of creating presence for, authorisation by and accountability to affected constituents. We identify how these logics can become complementary and enable the formation of representative alliances that strengthened the transnational representation of worker interests with regard to factory safety. Complementarity endowed input legitimacy to the Accord as a governance response at the transnational level. But our findings also document how conflicts undermined the alliance, which points to the contested nature of transnational representation.

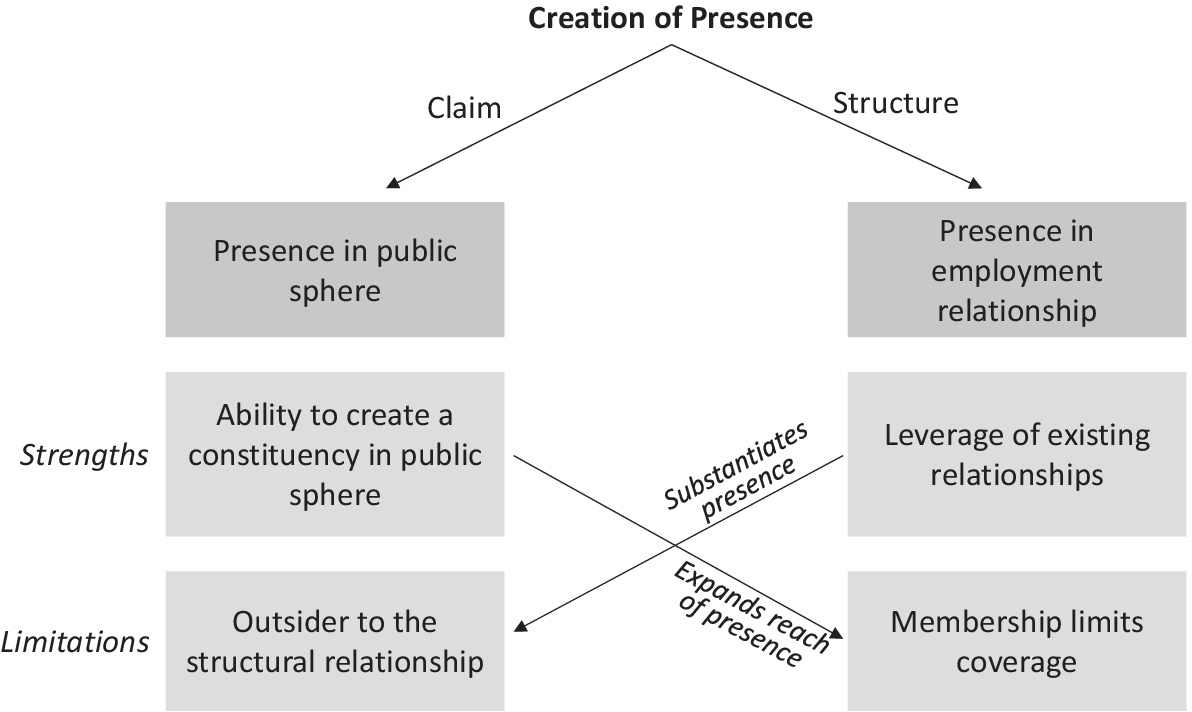

Creating Political Presence of an Affected Constituency

Democratic representation depends on the ability to bring affected constituents—here workers—and their interests into the political process. Thus the first dimension of making representation legitimate is whether it makes the affected constituency present. As depicted in Figure 2a, we identified the logic of creating presence in the public sphere through attention versus in the sphere of employment relations through membership as analytically relevant for understanding when modes of representation become complementary or clash. In the Accord, the representative alliance between NGOs and unions brought together representative structures and claims in such a way that each actor’s respective strength partially compensated for the other’s limitations: NGOs’ ability to create a constituency in the public sphere by generating attention through campaigning and mobilising public pressure expanded the political presence of workers and thereby compensated for low union coverage in Bangladesh. In turn, GUFs’ ability to leverage existing relationships in the sphere of the employment relationship at both the upstream and downstream ends of the supply chain—affiliate membership links with Bangladeshi workers and Western brands—provided substantiated presence that allowed the GUFs to turn public pressure into negotiated agreements.

Figure 2a: Representative Alliances Based on Complementarity

Complementary Spheres of Representation

In creating the Accord, representation by unions and NGOs became highly complementary in expanding coverage of affected constituents. With fewer than fifty out of more than four thousand factories with unions at the time of Rana Plaza, according to the AFL–CIO Solidarity Center, the vast majority of garment workers were not covered by representative structures. Existing unions were highly fragmented in multiple associations and lacked effective organising resources. As a result, the Bangladeshi unions’ ability and legitimacy to negotiate collectively with employers in Bangladesh, let alone with multinational brands on behalf of Bangladeshi garment workers, was limited.

For these reasons, unions highlighted that the Accord would not have been possible without the NGOs’ ability to create political presence for Bangladeshi workers in the transnational public sphere: “We wouldn’t have the Accord without them [the NGOs]. It would not have happened ” (GUF AFootnote 3). NGOs could give presence to the interests of workers: “In cases like Bangladesh, where you haven’t got mature systems of industrial relations. . . they [NGOs] provide another avenue towards worker representation” (Accord A). In the aftermath of Rana Plaza, NGOs were able to draw global media attention and public anger to the plight of workers through intensive campaigning and outreach, as a unionist acknowledges:

The campaigning role that they have that they’re able to go out and put public pressure on companies to sign the Accord has been invaluable. Because we simply wouldn’t have had the capacity to do that and we wouldn’t have anything like the number of companies that we have that have signed the Accord (GUF A).

Online campaigning networks SumOfUs or Avaaz created additional “surge capacity” (Online Campaign B). Their online petitions encouraged their large subscriber base to use their voice as citizens and consumers to demand brands to “Protect your workers. Sign the Bangladesh Safety Accord now,” as SumOfUs demanded. Thus, by mobilising the “massive, public outcry” “on tipping-point moments of crisis and opportunity” (Online Campaign A), such as Rana Plaza, representative claims expanded the reach of representation. This powerfully brought into being a constituency—Bangladeshi workers—linked to Western brands and their consumers.

However, campaigners lacked the relationships with companies to negotiate binding commitments that were enforceable by actors within the employment relationship. In contrast, GUFs enjoyed strong relationships with several European brands. IndustriALL and UNI Global had international framework agreements (IFAs) in place with the most important buyers sourcing from Bangladesh—Inditex and H&M—and were able to leverage these existing relationships on behalf of Bangladeshi workers to convince these brands to sign the Accord. Unions and NGOs celebrated their representative alliance as “a really good demonstration of the division of labour between the different types of organisations and the roles that they play in this” (GUF A). Both realised that by “working collaboratively together we bring different things,” which “together actually it’s a really strong force for change” (NGO A.1).

Competing for the Sphere of Representation

Our findings show that conflict occurred when unions and NGOs competed for creating presence within the same sphere of operation. This is illustrated in the latent conflict over the right to represent workers on the Accord Steering Committee. While the labour caucus had insisted on equal representation of corporate and labour interests, clashes started to resurface in terms of deciding who represents labour. Despite low membership in Bangladesh, union interviewees insisted that the Accord—a collective agreement between unions and companies—existed within their sphere of operation. They claimed the right to be full signatories with 50 per cent voting rights on the Accord Steering Committee, with one vote each for the Bangladesh IndustriALL Council, IndustriALL, and UNI Global: “we play a representative role because we’ve representative structures” (GUF A).

The four NGOs were to be “witness signatories” with observer status, but without voting rights. NGOs somewhat reluctantly “agreed to play that role” (NGO A.1) in recognition of their role vis-à-vis that of a union:

We don’t technically represent workers. . . . Ultimately, we had to respect certainly what the unions wanted. You know, we have long-term working relationships with the local unions in Bangladesh. . . and we respect their role as the body that represents workers. Although we certainly would have liked to be signatories, we respect their decision (NGO A.1).

The Worker Rights Consortium and the Clean Clothes Campaign agreed that their “role is more sort of an advisory role and being able to support the unions where we can” (NGO B.1).

The reluctance of unions to cede a seat on the table reflects unions’ “long-held suspicion” that NGOs seek “to occupy the space that trade unions should be in,” as a campaigner herself noted (NGO B.1). “We have a very big problem with that. We certainly fight with that” (GUF A), a trade unionist explained. The difference in status in the Accord governance structure was seen as an important acknowledgement of the unions’ representative role in the employment relationship:

This to me is an acknowledgement by the NGOs of what the role of an NGO is vis-à-vis the role of a trade union. And it’s when those roles get confused that we run into difficulties. . . . But in the context of the Accord it is a lot easier to deal with because those roles have been made very clear from the start. They’re the campaigning organisations, and we are the representative membership-based organisations that have the power to enforce the Accord on behalf of our members (GUF A).

In sum, if NGOs compete within the same sphere of operation as unions, encroaching upon it, it does not expand overall presence but risks undermining the legitimacy of representation altogether. In our case, we saw how this latent conflict surfaced and was averted only because NGOs yielded to union demands.

Authorisation by an Affected Constituency

Ideally, affected constituencies are able to authorise the creation of their political presence. But in the context of global supply chains, it is often not even clear who the authorising constituency is and how they can authorise representatives. As depicted in Figure 2b, the interplay of discursive and structural sources of authorisation can complement each other’s limitations. NGOs source discursive authorisation from the public sphere by generating attention to claims. This affords them greater “plasticity” in who and what issues are represented. Plasticity in authorisation expands an authorising constituency beyond the boundaries of structural relationships to those who would otherwise be excluded from transnational representation, such as dead victims or non-affiliated unions. In turn, a union’s ability to source authorisation from its membership and affiliation with local union members provides unions with an explicit mandate. This substantiates representative claims, which alone remain precarious due to relying on surrogate authorisation, that is, not having been explicitly mandated from an authorising constituency. Cross-authorisation allowed NGOs and GUFs to present the Accord as a demand from Bangladeshi workers, though the extent to which workers were aware of the Accord at the workplace level has been questioned (Kabeer et al., Reference Kabeer, Huq and Sulaiman2020).

Figure 2b: Representative Alliances Based on Complementarity

Complementary Sources of Authorisation

In creating and implementing the Accord, NGOs could fill representative gaps where unions lacked a mandate to represent. The plasticity of representative claims allowed NGOs to represent dead victims of the Rana Plaza tragedy even if they were never formally authorised by them. Immediately after the disaster occurred, Dhaka-based investigators from the Worker Rights Consortium photographed and collected documents, tags, and labels amidst the rubble with the aim of “putting together testimony about the brands that were sourcing from the factory” (NGO A.1). Even if some brands claimed they did not source from Rana Plaza, justifying the representative claim through evidence from the ground allowed activists to demand compensation from brands on behalf of the dead and injured.

In turn, international unions utilised their global union networks to legitimise their role as making demands on behalf of Bangladeshi workers. This was necessary because low levels of union density in Bangladesh meant that widespread authorisation by actual union members was lacking. A trade unionist from the United Kingdom’s Trades Union Congress (TUC) describes how bringing the voice of a prominent Bangladeshi trade union leader to the United Kingdom put brands under pressure to yield to a demand that came directly from a Bangladeshi unionist:

We got Amirul [Haque Amin, president of the National Garment Workers Federation in Bangladesh] to speak at the TUC Congress. . . . That was a very important moment because it marked the kind of solidarity that got lots of the UK brands to sign up. . . . So you’ve got that interplay between the global unions, the national unions, and the backing of the Bangladeshi unions there (TUC A).

Thus Bangladeshi trade unionists played a key role in adding urgency and legitimacy to international unions’ demand for brands to sign the Accord:

It [the Accord] didn’t have that feeling of like, ‘oh, the West telling the Global South what to do.’ Because we were having Bangladeshi union leaders coming here and saying what we want you to do is sign the Accord. . . . So it’s something that trade unions actually want (TUC A).

The representative alliance between transnational labour activists and international and local unions added the necessary input legitimacy to the Accord so that it became seen as the “legitimate” response to Rana Plaza, putting pressure on brands to sign it. Nevertheless, it is worth highlighting that at no point have Bangladeshi workers ever voted on and thus authorised the Accord as a collective agreement covering their working conditions. This highlights the limitations of transnational solidarity strategies to ensure authorisation of representation.

Our findings also show the cross-authorisation of unions and NGOs in implementing the Accord. GUFs actively supported their affiliated unions in the IndustriALL Bangladesh Council in pursuing claims under the Accord. However, non-affiliated Bangladeshi unions lacked such structural relationships with GUFs and thus lacked representation within transnational governance. In one case, twenty to thirty workers were sacked in a unionised factory in retaliation for trying to exercise freedom of association over safety concerns and for participating in the Accord. At a later meeting at the factory to investigate the issue, workers were physically attacked by factory managers in front of Accord and brand staff. When the factory owner came under pressure to sack the managers, he instead shut the factory. All workers lost their jobs. Under the Accord, brands now had the duty to ensure compensation for workers due to factory closure and to find alternative work.

Owing to its complexity, the workers’ union requested support to handle the case and defend its members’ rights to compensation. But IndustriALL was not authorised to represent the union not affiliated to the IndustriALL Bangladesh Council. In contrast, the Worker Rights Consortium could support unions regardless of whether they were IndustriALL affiliates. The NGO helped the union secure compensation and find alternative employment for workers in three ways: first, by preparing documentation to establish the case; second, by acting as a liaison with the Accord; and third, by interacting with brands on behalf of the workers. This case demonstrates, first, the way in which the Worker Rights Consortium gained authorisation by being asked to step in; second, its ability and willingness to represent the case of the workers, regardless of the constraints of representative structures; and third, its ability to escalate issues up the supply chain and represent workers vis-à-vis brands.

Competing Sources of Authorisation

When different sources of authorisation compete with one another, it becomes unclear who the democratically relevant authorising constituency is and whose claim is legitimate, leading to potential conflict over representation. In our case, the NGOs’ plasticity that allowed them to represent Rana Plaza victims also clashed with the explicit mandate of unions to implement the Accord. This is illustrated in the joint campaign between the United Kingdom’s TUC and Labour Behind the Label, the UK chapter of the Clean Clothes Campaign, against Edinburgh Woollen Mills. The UK knitwear company was targeted on two fronts: first, for its refusal to sign the Accord, and second, for its failure to pay adequate compensation for victims of the Tazreen factory fire in 2012, when 112 workers died.Footnote 4 The joint action, planned to take place outside a number of Edinburgh Woollen Mills stores across the United Kingdom on the Tazreen anniversary, was celebrated as a coming together of the British trade union movement and civil society: “Not only do you have the whole union movement, 6 million workers in the UK, but there’s a broader based alliance. . . with all those different NGOs coming together” (TUC A). However, just a few days before the planned action, Edinburgh Woollen Mills signed the Accord. This led to a divide between the unions and the NGOs. The TUC called off the “wonderfully planned” (TUC A) day of action and commended the company for signing the Accord. One union interviewee (TUC B) admitted that signing the Accord “obviously doesn’t solve the compensation issue.” Yet, their mandate was to strengthen the Accord as an institution that could prevent future fatalities.

In contrast, NGOs saw only marginal benefit in getting another signatory to the Accord, which at the time had already secured more than fifty signatories, including large retailers. NGOs established themselves as representatives of the dead, injured victims and their families. Labour Behind the Label had invested considerably into the campaign for victim compensation and was unwilling to let the company get away with what it saw as an “attempt to undermine any kind of calls for compensation,” as one campaigner stated:

The frustration from our side is that in the rush to celebrate the victory of the Accord there’s been a tendency to sweep under the carpet the reality that those families affected by the [Tazreen] disaster still don’t get anything (NGO B.1).

In sum, this case illustrates how unions’ structural boundaries of representation meant that they focussed more narrowly on their mandate to build the Accord. In contrast, NGO’s high plasticity allowed them to focus on seeking justice for a neglected group of victims, who were bereft of a voice. Eventually, an agreement driven by IndustriALL, the fashion retailer C&A, the C&A Foundation, and the Clean Clothes Campaign led to total compensation of US$2.17 million for Tazreen victims. However, the conflict damaged the representative alliance between the TUC and Labour Behind the Label in the United Kingdom.

Accountability to an Affected Constituency

The final dimension for establishing democratically legitimate representation concerns sources of accountability. To establish legitimacy in the public sphere, self-appointed representatives must demonstrate public reputational accountability by drawing attention to their claim. To establish legitimacy in employment relations, unions must demonstrate accountability to their members and affiliates. As depicted in Figure 2c, different means of sourcing accountability—attention versus membership—were mobilised in complementary ways: NGOs’ freedom to agitate and direct their claims to wherever they can generate most attention expanded avenues to accountability where unions were restricted by structural boundaries. In turn, a union’s structures of affiliation across the supply chain grounded claims in concrete chains of accountability. In contrast, forms of accountability undermined the other when the NGOs’ focus on generating public attention undermined the unions’ accountability to their membership base.

Figure 2c: Representative Alliances Based on Complementarity

Complementary Sources of Accountability

Without a clearly defined authorising constituency, it is even less clear how workers can hold self-appointed NGO representatives accountable. Lacking such substantive authorisation, NGOs sought reputational accountability by basing their claims on those made by Bangladeshi workers themselves while placing them where greatest attention could be generated. As an example, in 2018, the Clean Clothes Campaign launched a public campaign under the hashtag #WeDemandTk16000 in support of Bangladeshi unions’ campaign to increase the national minimum wage for garment workers. As seen in this example, representative claims can be ambiguous about their “object” of representation: the #We can refer to either or both the Bangladeshi worker and/or the Western consumer as the constituent of the claim. NGOs presented themselves as transmitters of workers’ own demands into global discourses to build legitimacy around their claims and enhance their reputation as “authentic” claim makers. Moreover, rather than focussing on Bangladeshi institutions or employers (Kang, Reference Kang2021), this representative claim is directed at where greatest attention can be generated: brands and their consumers.

In turn, Bangladeshi unions started to use NGOs’ attention-based reputational accountability to diffuse strategically their claims in global discourses to compensate for their weakness in actual membership. One example of this is the practice of collecting labels. We visited a union’s emergency meeting at a Bangladeshi union federation’s office. About thirty mainly female workers had gathered to discuss how to deal with an urgent dispute where a number of workers had just been sacked for raising safety concerns. The union was planning its strategy to negotiate with the employer to reinstate workers. Union members had collected the labels of the brands for which they had been producing, including production dates and order volumes. Rather than calling on their members for strike action if negotiations with employers stalled, their plan was to work with the Worker Rights Consortium and Clean Clothes Campaign to mobilise reputational threats against the brands sourcing from their factory. In this case, the dispute was solved locally. However, in other cases, NGOs were called to step in and put pressure on brands through reputational threats, and the brands in turn would put pressure on their suppliers to resolve labour disputes. Vice versa, Bangladeshi unions mobilised NGOs’ attention-based reputational accountability to put pressure on their employers via northern consumers and brands, thereby increasing their ability to be “acting in the interest of the represented” (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967: 209).

Competing Sources of Accountability

Our findings also reveal how significantly different sources of accountability create conflict undermining representative alliances. This is illustrated by a conflict that emerged in the implementation of the Accord. Two years into the Accord, progress in improving worker safety was proving slow. Fewer than half of all safety issues had been tackled. Seeking to hold companies accountable for ensuring that safety upgrades were being made, in mid-2015, the Clean Clothes Campaign and Worker Rights Consortium launched a public campaign against H&M by publishing an analysis of the retailer’s remediation progress. The analysis revealed that the vast majority of H&M’s suppliers were far behind schedule in making the required safety repairs. As witness signatories, NGOs viewed their relative “outsider” position as endowing them with the freedom to act outside standard processes and launch the solo-run campaign to generate public pressure via the public sphere: “Ideally there wouldn’t be any need for public pressure. But NGOs don’t have enforcement power under the agreement. We can’t initiate dispute, and that frees us to use alternate means” (NGO A.2). The NGOs admitted that H&M was one of the better performers. But they felt that public reputational accountability could best be achieved by drawing attention to the failures of a highly visible brand to create maximum attention with consumer audiences.

This public attack on H&M was highly controversial, particularly for IndustriALL, whose international framework agreement with H&M meant that they represented garment workers throughout H&M’s supply chain, not just in Bangladesh but across the world, including in other developing countries. Unions felt that attacking H&M, one of the best-performing brands in the Accord, was counterproductive. They accused NGOs of being “short-sighted ” and of using the public campaign against H&M to “feed their campaigns” (GUF A) to sustain an approach that relied on generating attention and external visibility. Whereas NGOs enjoyed “freedom to agitate” because they lacked direct accountability for the effects of their campaigns, unions were constrained in their actions by “that great responsibility of accountability to our members” (GUF B). They were reluctant to do “lasting damage” to their relationship with H&M because this could harm their ability to represent workers in other supply chains:

We often are in a situation that we or our affiliated unions in the countries have good relationships with these companies. And they have to make a judgement call in terms of how far they can go without really putting lasting damage to these relationships (GUF B).

Unions therefore opted for the internal route of putting pressure on Accord signatory brands through bilateral negotiations, rather than reverting to public pressure: “We would always rather try and negotiate things than go out after companies publicly or resolving issues publicly” (GUF B). As full signatories to the Accord, the unions also viewed the Accord as a joint programme that both corporate and labour signatories had to deliver—they were jointly accountable for its success or failure. Thus the unions targeted the worst performers that most flouted their obligations under the Accord. Targeting high performers would create little incentive to engage in meaningful cooperation going forward. In sum, being accountable to their membership across all supply chains meant that unions had to take a more balanced approach that delivered on the terms of the Accord, but without putting lasting damage on relationships elsewhere.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we have argued for the need to develop a more nuanced understanding of democratic representation as a central dimension of input legitimacy in transnational governance. Our aim was to develop a theory of transnational representation that provides the conceptual tools to understand how it is performed and by whom, and if and how the practice of democratic representation can be improved. A starting point for our analysis was the acknowledgement that democratic practice in transnational governance no longer depends on a pre-existing, territorially bound constituency or electoral forms of representation. This is because electoral constituencies typically fail to coincide with those affected by the social consequences of global economic activity (Bohman, Reference Bohman, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012; Disch, Reference Disch2012).

A core challenge is therefore to bring into being a transnational constituency of those affected by a global supply chain and give political presence to this constituency. This raises the question, on what basis can a particular constituency be represented, by whom and how? We focussed on labour governance at the transnational level and presented a framework explaining the interaction of two approaches to transnational worker representation—representative claims and representative structures. We argued that, owing to the systemic challenges of the supply chain context, neither approach is ideal. Our findings demonstrate on what basis complementarities can emerge between them that improve, but not perfect, democratic practice.

Here we will focus on the general insights arising for transnational representation. As illustrated in Figure 3, at its core, our framework consists of three interrelated dimensions: creating political presence for, authorisation by and accountability to affected constituents. In conjunction, they combine to create input legitimacy. Authorisation justifies the creation of presence: being authorised by a constituency justifies the representative to create presence on behalf of the represented. In turn, creating presence requires accountability: representatives must be accountable for how they represent. Representation is likely to be an ongoing process where the relationship between authorisation and accountability is iterative. Broadly speaking, authorisation reinforces accountability: authorisation endows representatives with a mandate to represent, which means representatives are accountable to act upon that mandate. In turn, accountability reinforces authorisation: demonstrating accountability justifies the authorisation in the future.

Figure 3: Representative Alliances Based on Complementarity

On the basis of our framework, we argue that the interaction of representative claims and structures can strengthen democratic representation if it 1) makes affected interests politically more present, 2) enables authorisation by a greater number of affected interests, and 3) creates stronger forms of accountability to affected interests than without the interplay. Our case suggests that this happens when approaches are able to compensate at least partially for each other’s limitations. As depicted in Figure 3, the strength of representative claims is that they can expand presence, authorisation, and accountability and at least partially fill representative gaps by including those who would otherwise be excluded from structural forms of representation in transnational governance. In turn, the strength of representative structures is that they can substantiate claims.

Our framework also offers insights into the politics of input legitimacy by explaining how these logics of representation drive the political dynamics of whose interests get represented and how representation is performed. Just like parties vie for the right to represent constituencies in electoral politics, transnational representation is the outcome of political processes: competition and collaboration amongst potential representatives who must demonstrate their legitimacy to represent. In the Bangladeshi case, because of the unions’ weak local representative structures, representation tilted to where structures were strongest, namely, GUFs’ representative structures and their relationships with Western brands. For NGOs, the ability to make claims was strongest within a Western media–dominated global public sphere, where they could generate most attention. The interplay between both created representation where both were strongest: representation was targeted at Western brands and their consumers, rather than at Bangladeshi employers. Our framework also explains who were not represented. In a globally interconnected economy, there are potentially multiple affected constituencies. In our case, Bangladeshi workers who did not produce for Western brands or workers across the rest of the supply chain (cotton growers, weavers, transport workers, etc.) were also not represented.

Contributions

Our first contribution is to the scholarship on private transnational governance and the normative question of its input legitimacy. While scholars have begun to develop criteria for assessing the democratic legitimacy of private regulatory processes (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012), insufficient attention has been placed on a question that occupies a central role in both political theory (Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1997, Reference Scharpf2003; Urbinati & Warren, Reference Urbinati and Warren2008) and business ethics scholarship (Soundararajan et al., Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019)—democratic representation of affected constituents in rule-making processes as central to input legitimacy. By bringing into conversation the business ethics scholarship on private transnational governance (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Gilbert & Rasche, Reference Gilbert and Rasche2007; Schormair & Gilbert, Reference Schormair and Gilbert2021) with the scholarship on industrial democracy and normative democratic theory, we developed a conceptual framework that provides a normative orientation for better evaluating the input legitimacy of transnational governance regimes. While accepting that, in empirical terms, the criteria of presence, authorisation and accountability will be insufficiently met, as in our case, the framework nevertheless equips scholars and practitioners with an analytical tool better to assess, evaluate and critique stakeholder representation.

Moreover, by conceptualising complementarities in the different logics of transnational representation, our framework can inform the design of collaborative multi-stakeholder governance. Transnational governance systems need to create not just deliberative institutions—stakeholder governance models—but also representative systems. By providing a better understanding of how the logics of representation drive political processes and shape what and how interests get represented, initiators of private governance schemes can take more informed decisions when developing representational mechanisms. Our findings suggest that representative structures will be most effective when there is high coverage of affected groups by structural representation. Representative claims will be most effective when there is the need to expand representation to constituencies beyond those who are covered by structures. This can be the case when there is little or no coverage of affected groups by structural representation, such as seen in our case with Bangladeshi workers, but also with informal or seasonal labour or future generations, who by definition cannot yet mandate their representatives. Representative alliances between both are powerful in offering transnational expansion of structural representation, such as NGOs which translate demands made by local communities into consumer contexts, where pressure on brands can be generated.