Introduction

This visual essay centres on a museum collection dedicated to the preservation of physical endings, both of a single life and across geological time. Johannes Weigelt (1890–1948), a German palaeontologist and geologist, was the first person to posit that to understand fossil formation in the ancient past, post-mortem processes should be examined in the present – an approach that would eventually become the field of taphonomy in current palaeontological research.Footnote 1 In the course of his professional career, Weigelt recovered dozens of fossil specimens and produced copious photographs that documented his fieldwork and laboratory analyses. These are currently stored at the Geiseltalmuseum, an institution founded by Weigelt in 1934 which remains in its original location to this day: a sixteenth-century chapel in downtown Halle (Saale), Germany. The exhibition hall still holds skeletons and other material under glass vitrines and in storage cabinets, some kept intact since the museum's inauguration. All of these are now part of the Central Repository of the Natural Science Collections at the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. Closed to the general public in 2011, the Geiseltalmuseum renewed limited visitor access in 2018 and serves as a working palaeontological collection to be accessed and used by scientists.

Weigelt's photographs have been the subject of less attention than has his specimen collection, scattered throughout different departments of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. Those held at the Geiseltalmuseum include fieldwork documentation and publication plates, in addition to personal photographs that reveal Weigelt's entrenched ideological allegiance to the National Socialist German Worker's Party. Yet Weigelt's archive provided a surprising discovery in August 2016, when Dr Meinholf Hellmund (the late curator of the Geiseltalmuseum) and myself came upon over forty photo-collages in an uncatalogued box, presumably donated by his family decades after his death. Bearing a striking resemblance to works by Dada artists, the provenance of these previously unknown collages was unclear, as were the exact dates when they were created. However, several of the images incorporated in the collages indicate Weigelt as the maker, and suggest that these were produced during the early to mid-1930s, roughly the period when the Geiseltalmuseum was founded. Such timing is perplexing, both due to the work that Weigelt was putting into the creation of his museum and in light of his membership in the National Socialist Party. This fervent political affiliation would eventually account for the subsequent relegation of Weigelt's academic production from national and international circles after the Second World War.

Unusually for BJHS Themes, this is a visual essay in which the images and their collocations provide the argument. The medium of collage serves as a touchstone, allowing for the juxtaposition of photographs, documents and ephemera in the presentation of Weigelt across different stages of his academic career. Much like a collage, the collection of images and text presented here creates contrasts and disjunctions that question Weigelt's scholarly oeuvre. For example, how does one reconcile Weigelt's creative pursuits with the overarching Nazi condemnation of Dadaism during the Third Reich? What is revealed or concealed in this arrangement of photographs and printed matter, and the manner in which remnants of prehistoric epochs are combined with snapshots of a more recent past? And what was the ultimate motivation for Weigelt's collage making, in relation to both his academic writing and the expansive role of photography in his larger body of work?

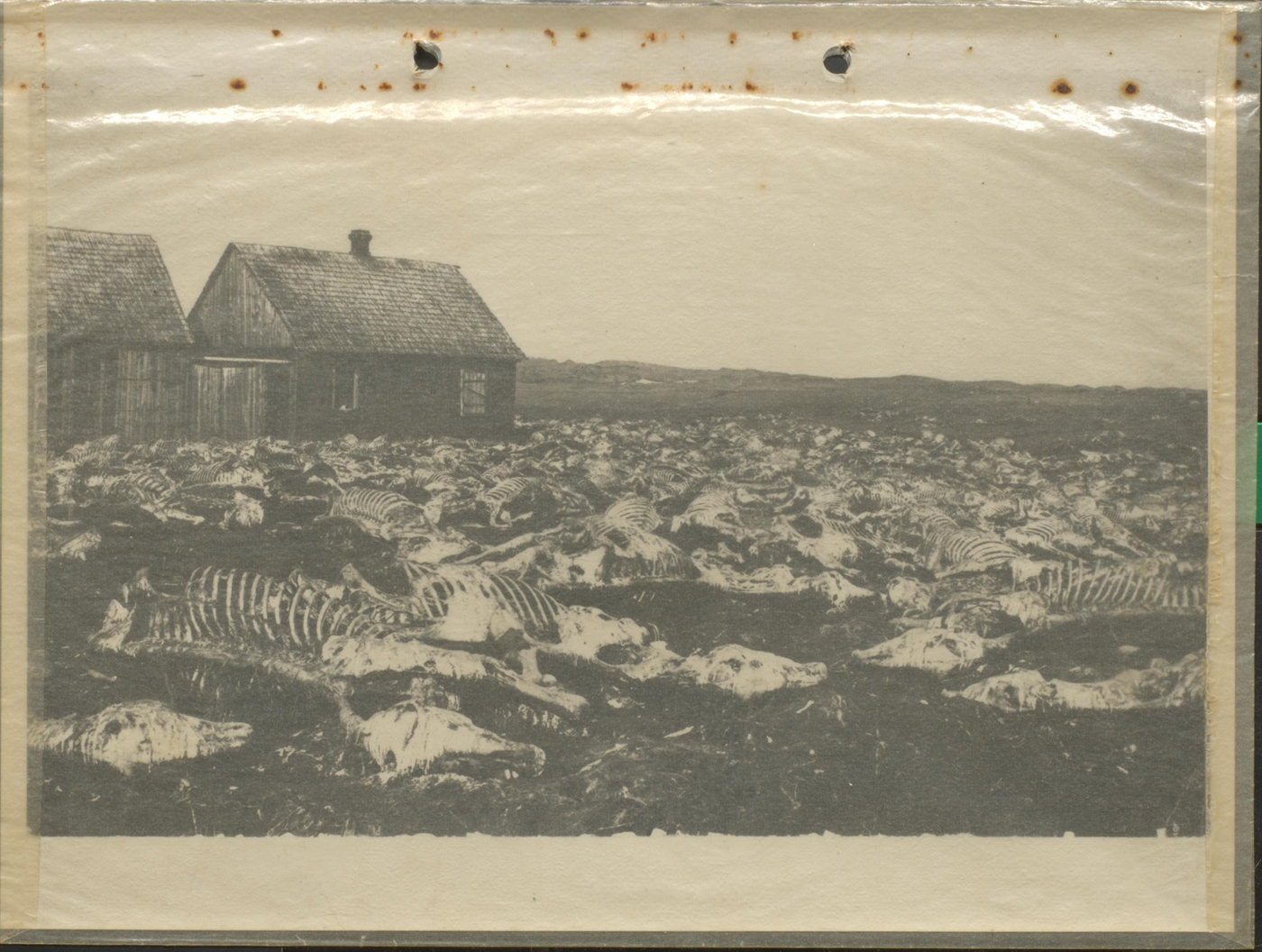

Figure 1. This is the frontispiece to Weigelt's Recent Vertebrate Carcasses and Their Paleobiological Implications (1927). The photograph is dated to the spring of 1918. The caption reads, ‘Carcass assemblage [Leichenfeld] of horses that died of starvation, near Kralwaka, west of Dünaburg [now Krāslava and Daugavpils in present-day Latvia]; these horses were turned out into the fields after the Russian Revolution broke out.’ Weigelt makes no further mention of the circumstances behind this image in his book, yet the equine skeletons harken to photographs of staggering war casualties during the First World War. The term Leichenfeld became a commonplace German trope during the Great War to describe mass casualties in the battlefield. It is unclear whether this is the origin of Weigelt's palaeontological use of the term; what is certain is that, as a soldier of the German Imperial Army (see Figure 6), he would have been privy to its currency.

These questions still await conclusive answers, as does analysis of the content and formal construction of these collages. But Weigelt's assemblages – fossils in the field, specimens in the museum, and photographs in the archive – offer the opportunity to reflect on how scientific collections come to an end, a concern that resonates with other contributions to this BJHS Themes issue. Indeed, taphonomy offers a broader conceptual framework from which to interpret German excavation sites, the Geiseltalmuseum and Weigelt's Nachlass (his collection of manuscripts, letters, notes and other documents). Here, taphonomy is not just a means to examine biological and geological traces in the fossil record, but also serves as a prompt for reflecting on the ideological evidence embedded in the exhibition and the private archive.

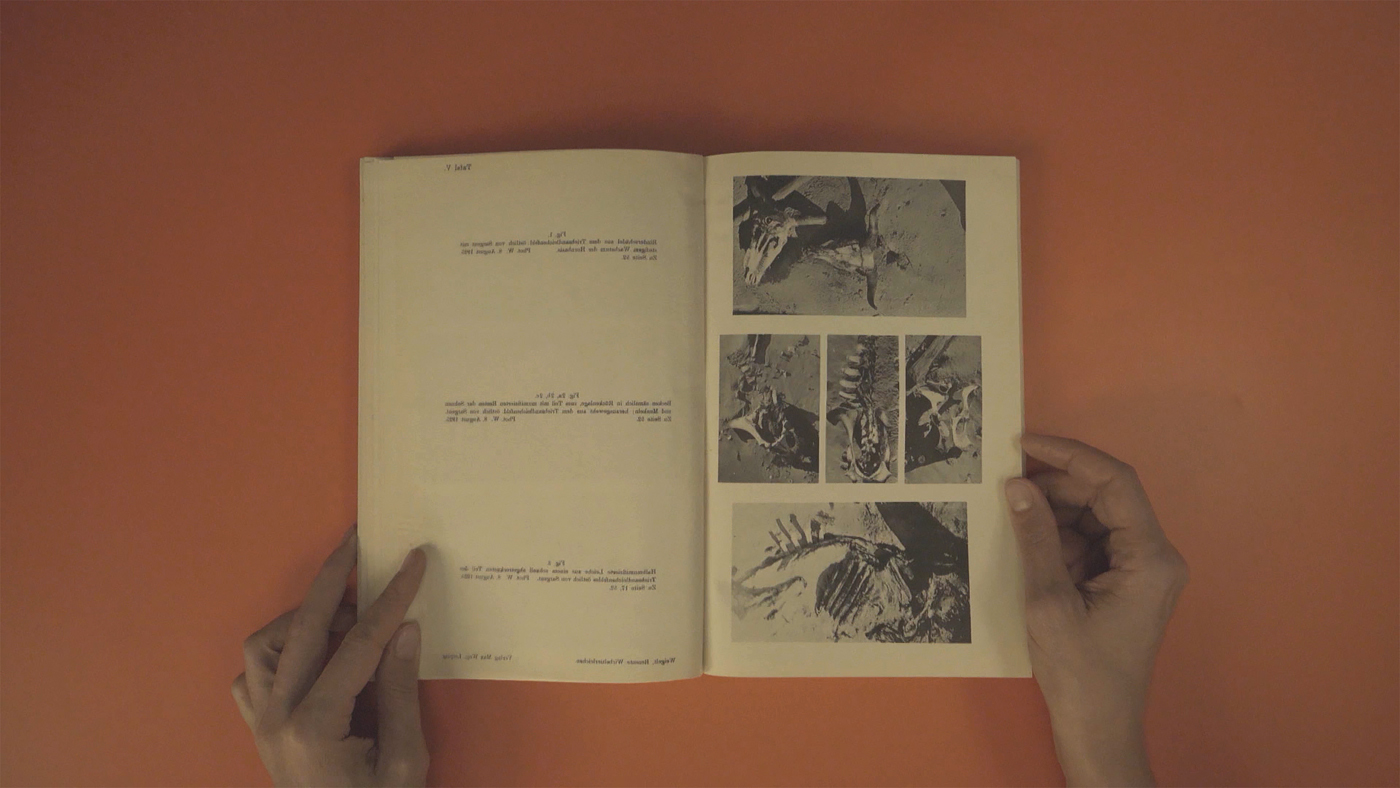

Figure 2. Internal view of Recent Vertebrate Carcasses and Their Paleobiological Implications. Plates in the posterior section of the book contain over a hundred black-and-white photographs of dead mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and fish. Weigelt writes the following in the preface: ‘With a few exceptions, the photographs – of carcasses that I myself found and examined – are my own. To avoid distortion, I often took them with a handheld camera looking down on the carcass from a point directly above it.’ The technical emphasis of his documentation style underscores Weigelt's attempt to demarcate decomposition of a carcass as a site of observation set within a larger milieu, both through compositional choices and as an analytical frame.

Frontispiece

In his 1927 monograph Recent Vertebrate Carcasses and Their Paleobiological Implications, Weigelt carried out a ‘full-scale research effort to document processes of vertebrate death, decay, disarticulation, transport, and burial’ as an attempt to understand fossil formation through ecological processes in the present.Footnote 2 Weigelt described this process as Biostratinomie – the earliest formulation of taphonomy, subsequently defined as such by Soviet palaeontologist and geologist Ivan Antonovitch Efremov in 1940.Footnote 3 The book features dozens of photographs of decomposing animals taken by Weigelt during fieldwork in the US Gulf Coast between 1924 and 1926. Weigelt drew parallels between these recent deaths and fossil specimens housed in the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, where he was university professor.

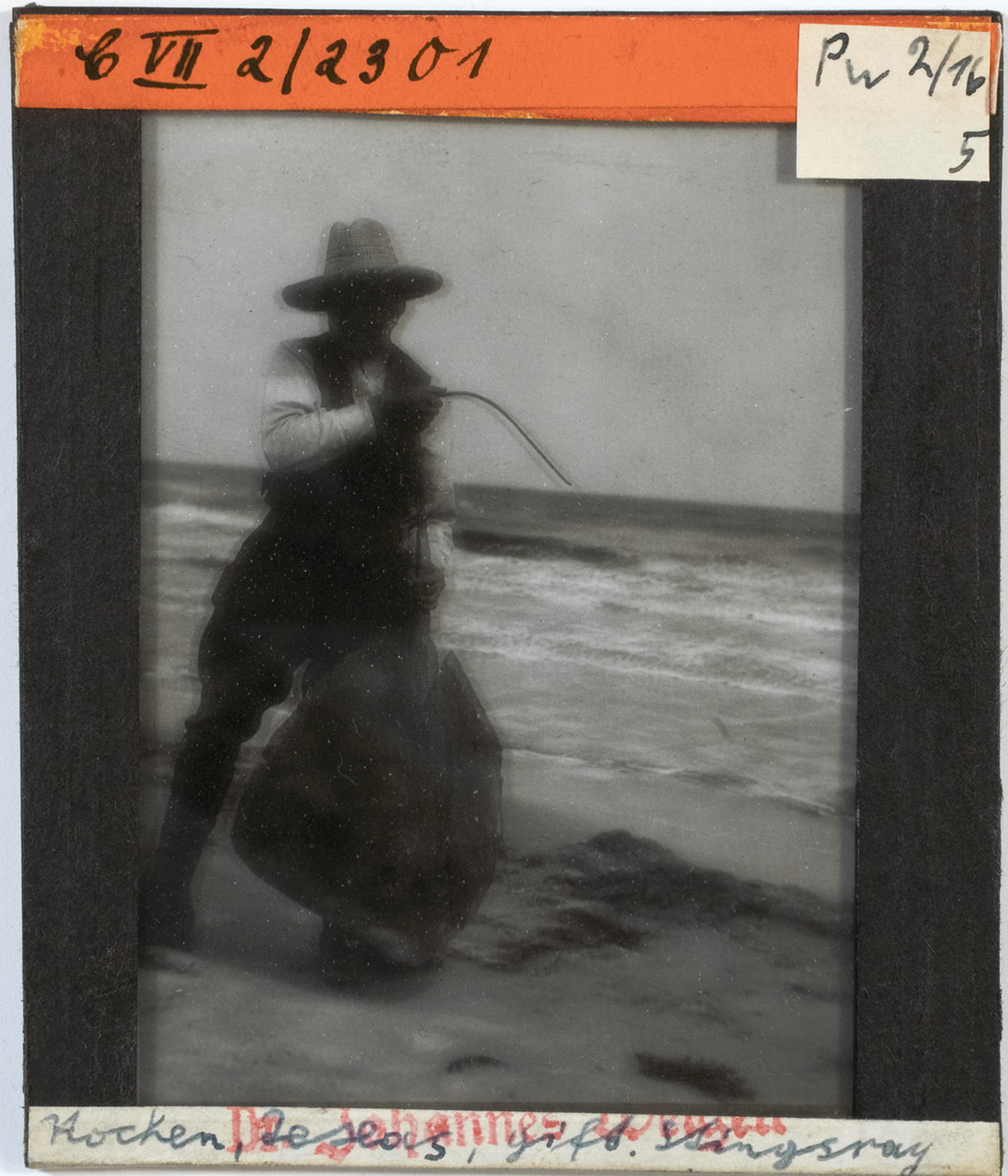

Figure 3. Glass negative of Johannes Weigelt holding a dead stingray. The words Rochen – German for the biological superorder Batoidea – can be read along with the word ‘stingsray’ (sic) in the handwritten caption. Hundreds of glass negatives exist of Weigelt's travels through the United States, specifically in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana. Courtesy of the Zentralmagazin naturwissenschaftlicher Sammlungen, Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (henceforth ZNS, MLU-HW).

A central element of Weigelt's understanding of Biostratinomie was the concept of Leichenfelden, the German expression for ‘corpse fields’. Weigelt used this term throughout Recent Vertebrate Carcasses and Their Paleobiological Implications to describe large-animal carcass assemblages in the fossil record – sites where a combination of aquatic and geological depositional conditions allowed for the preservation of numerous intact specimens, if not entire ecosystems. Often animals would become trapped in the mud, dying in the same substrate that would later preserve their remains.Footnote 4 In addition to dead animals, Weigelt also photographed sites that he identified as potential Leichenfelden during his fieldwork in the US Gulf Coast, such as strandlines in swamps, flood areas, river meanders and other bodies of water, most notably Smithers Lake in Texas.Footnote 5 These contemporary locations provided a window for Weigelt onto how ancient ecologies came to be, while also merging biographic and historical information with his palaeontological explorations.

Figure 4. An example of a Leichenfeld, or carcass assemblage. The translated caption in English reads, ‘Swath of driftwood and carcasses on the south shore of Smithers Lake [Texas]. February 1925’.

Figure 5. This photograph, presumably taken at the same time as that of the frontispiece to Recent Vertebrate Carcasses and Their Paleobiological Implications and showing the horse skeletons from a different perspective, was found among Weigelt's papers in the University Archive of Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. Image scan provided by the Universitätsarchiv, MLU-HW (UAHW Halle, Rep. LVIII, No 419, Johannes Weigelt).

Figure 6. Postcard featuring Johannes Weigelt (bottom row, left), sent to his sister on 28 July 1914. Weigelt fought on the Western Front during the First World War and interrupts his descriptions of decomposition in Recent Vertebrate Carcasses and Their Paleobiological Implications with war-related anecdotal digressions, including the mass burials of Allied soldiers killed in France during the war. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

Figure 7. Among the most impressive fossils from the Geiseltalmuseum's collection is the adult female skeleton of an Eocene horse, Propalaeotherium hassiacum. The original fossil was recovered in 1933 and is still located today underneath a glass surface, encased in its original wax. At the time, this specimen was considered a potential keystone in tracing the ancestral lineage of the contemporary horse, an erroneous contention that has since been re-evaluated. Paraffin wax was used as an artificial substrate replacing the original lignite, a means to adhere fragile fragmentary fossils and transport them for preparation to the museum laboratory. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

From the ground up

The Geiseltalmuseum was founded by Johannes Weigelt to showcase well-preserved fossils of Eocene fauna and flora recovered from the open-pit lignite mines in the Geiseltal valley of central Germany. Since its establishment in 1934, the museum has displayed mural paintings and diagrammatic reconstructions of ecosystems that date back over fifty million years. In several of his writings on Leichenfelden, Weigelt describes the biodiversity of Grube Cecilie, one of the main excavation sites of the Geiseltal, closed permanently in 1993 and filled with water to form the Geiseltalsee.Footnote 6 There are 125 species of vertebrate alone among the several thousand fossils that comprise the collection of the Geiseltalmuseum; many of these were recovered by Weigelt from the brown coal deposits, and are now displayed alongside those extracted by subsequent generations of palaeontologists from the same mines. Among the most renowned fossils are the Propalaeotherium specimens discovered during Weigelt's direction of the Geiseltalmuseum. Considered at the time to be the ancestor of the modern horse, Weigelt referred to these specimens as the Urpferd, which translates to ‘original horse’ or ‘proto-horse’. Specimens of Propalaeotherium remain one of the Geiseltalmuseum's renowned highlights today.

Figure 8. Underlining the importance of the Propalaeotherium in the museum, a full-scale replica of the Propalaeotherium hassiacum specimen greets visitors from within a central vitrine in the exhibition hall of the Geiseltalmuseum. The replica was made in the year 2000; the total length of the skeleton is approximately ninety centimetres.

Figure 9. A wide-view photograph of the exhibition hall of the Geiseltalmuseum as it stands today.

Figure 10. Two views of the exhibition hall of the former Geiseltalmuseum while Weigelt was director. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

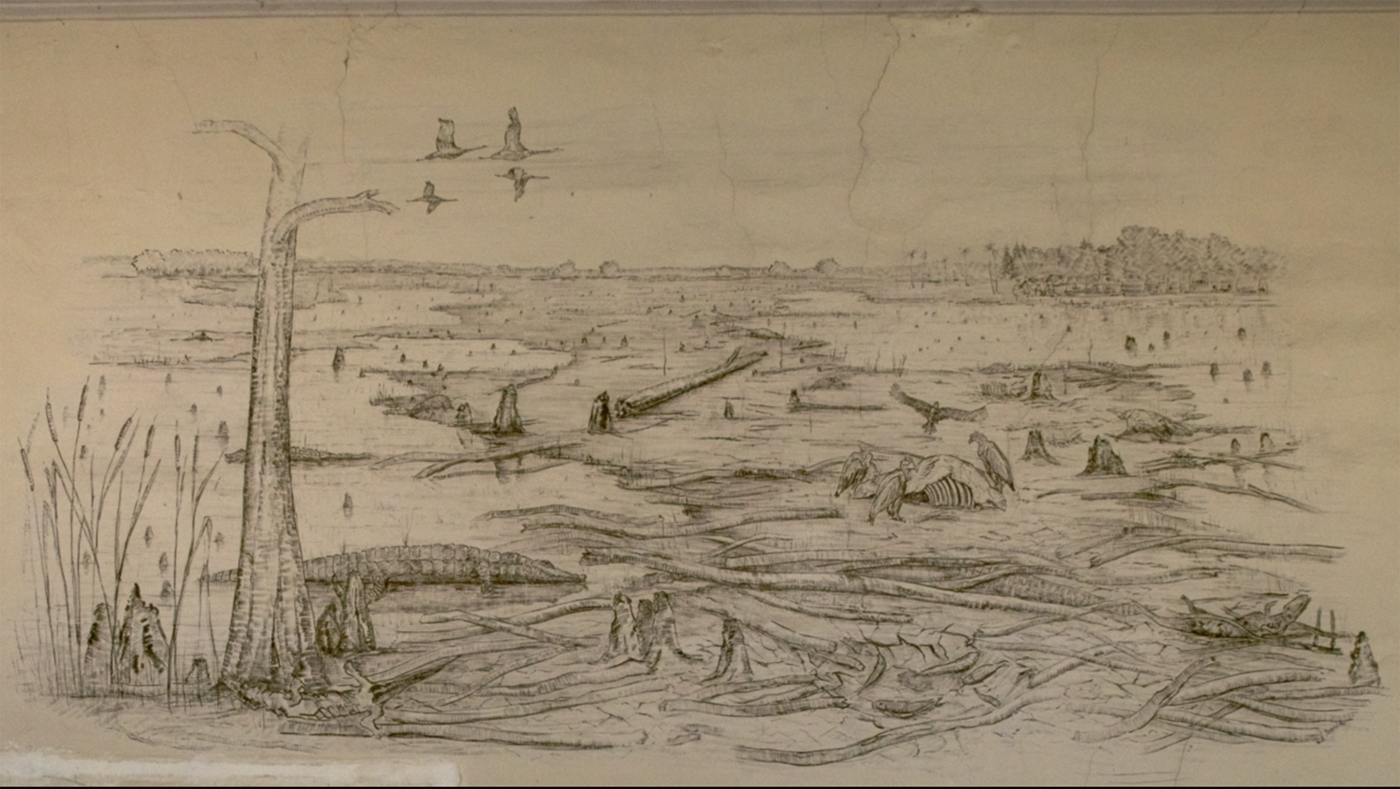

Figure 11. Later additions to the Geiseltalmuseum include six mural-size paintings made by Rudolf Dobrick in 1959. The scenes painted directly on the walls of the exhibition hall reconstruct landscapes of the Geiseltal ecosystem. The mural shown here, located on the back wall, depicts a Leichenfeld.

Figure 12. An annotated and diagrammatic representation of Rudolf Dobrick's Leichenfeld mural landscape on the back wall of the museum. The bottom caption reads, ‘Leichenfeld: animal carcasses in temporary bodies of water’. Animals highlighted in white identify species represented among the Geiseltalmuseum's holdings.

From 1934 onwards, the Geiseltalmuseum became a leading palaeontological institution in Germany – a progression aided by Weigelt's swift promotion from university professor (Professor ordinarius) to rector of the Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg. This advancement is largely attributed to Weigelt's fervent support of the National Socialist party during the Third Reich,Footnote 7 a fact Weigelt openly recognized in his public acceptance of this position.Footnote 8 Weigelt was known among his colleagues to coerce participation in the Nazi Party, in addition to unquestionably enforcing its discriminatory policies. Several testimonies by students and faculty from Jewish, Catholic and other marginalized backgrounds describe Weigelt's role in their removal from the Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, the precursor institution to the Geiseltalmuseum.Footnote 9 Weigelt served as director of the Geiseltalmuseum throughout his tenure as rector from 1936 to 1944.

Figure 13. Diagram of Grube Cecilie, c.1930. Grube Cecilie was a widely known mine in Germany: the site was the subject of a 1917 film documentary of the same name, presenting the fabrication of briquets through the eyes of a day labourer who migrates to work in the mines as a means to improve his family's standard of living. Note Weigelt's annotation of ‘Leichenfeld I’ and ‘Leichenfeld II’ (divided into quadrants) in the centre left of the image. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

Mining and unearthing

It is unclear exactly when Johannes Weigelt began creating photo-collages, but elements from these works place their appearance slightly before or during his tenure at the Geiseltalmuseum, matching the Nazi rise to power in Germany. If Weigelt did make them during the National Socialist period, he certainly would have been aware of the official Nazi position against Dadaism and all forms of avant-garde art, attacks that began in 1933 and lasted throughout the entirety of the Third Reich.Footnote 10 A precursor exhibition to Entartete Kunst, the infamous Nazi travelling exhibition of ‘degenerate art’, took place in the Kunstmuseum Moritzburg in January 1937 – only 350 metres away from the Geiseltalmuseum.Footnote 11 In fact, the Entartete Kunst exhibition itself was shown between 5 and 20 April 1941 at the Landesmuseum für Vorgeschischte, Halle's state museum for prehistory – a venue that surely would have been familiar to Johannes Weigelt.

Figure 14. A coal wall of an empty mining pit, presumably Grube Cecilie. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

Figure 15. Johannes Weigelt surveying the ground of Grube Cecilie with his walking cane. A possible translation of the caption in Latin would be ‘Live, grow, flourish and unearth corpses from the Geiseltal's carnage!’ The back of the photograph has the following handwritten inscription: ‘Cecilie, 1931’. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

Figure 16. Photograph of Johannes Weigelt among Nazi officials, including Hermann Göring. Weigelt is the figure with a broad-rimmed hat and dark coat holding a walking stick, his back turned away from the camera. Göring is the figure immediately to his left. The back of the photograph has the following handwritten inscription: ‘Salzgitter, 1937’. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

Excavations at Grube Cecilie in the Geiseltal were suspended from 1939 until well after the end of the Second World War. During this time, Johannes Weigelt became an official geology adviser to ore extraction operations for Salzgitter AG in Lower Saxony, which was part of the Reichswerke Hermann Göring. Salzgitter AG was one of the largest mining operations for the Third Reich in Europe, producing millions of tons of steel and ammunition during the war through the forced labour of thousands of Jewish and other concentration camp prisoners.Footnote 12 It is unlikely Weigelt would not have been aware of the ubiquitous and deadly exploitation administered at the mining sites he regularly visited in this capacity.

Figure 17. Johannes Weigelt working at his university office in Halle, 1940. Note the presence of two scissors and cut-outs of paper illustrations on his desk. Weigelt may well have used the same scissors for creating both layouts in academic publications and photo-collages. A pin bearing Nazi insignia is on the right lapel of his coat; the swastika is hardly visible due to overexposure. Credit: Ullstein Bild.

Figure 18. Photo-collage attributed to Johannes Weigelt. Among the cut-outs of paper illustrations are likely images taken from academic source material as well as print advertising, newspaper broadsheets or even personal photographs. A cityscape of Halle cuts across an article on trilobites, with additional printed-matter elements (note repetition of athletic figure in Figure 20). Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

Weigelt's cooperation with the Nazi Party led to his being awarded the Ritterkreuz des Kriegsverdienstkreuzes in 1945, the highest military honour for civilians during the Third Reich. This recognition, as well as his proximity to Göring specifically, flagged him to the Allies as a significant figure in Nazi circles. With the war over, on 24 June 1945, Weigelt was deported from Halle to Ober-Ramstadt in Hessen on board a train under US command due to his participation in the National Socialist Party. He was relocated to the Western Sector with other prominent Nazi scientists and intellectuals, such as biochemist and physiologist Emil Abderhalden, infamous for his ardent defence of eugenics.Footnote 13 Weigelt never occupied another academic position. He died a US prisoner of war in Klein-Gerau on 22 April 1948.

Figure 19. Photo-collage attributed to Johannes Weigelt. A magnified hand hangs over a scene featuring a mine railway, presumably taken during operations in Grube Cecilie. Overexposure to the right side of the image is likely related to the lightening effect applied to the hand. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

Post-closure

Johannes Weigelt's photo-collages leave viewers with more questions than answers. Their imagery freely intersperses reproductions of fossil specimens and technical shots from the Geiseltal mines with portraits of university colleagues and postcard scenes of Halle. Popular urban kitsch playfully slips into illustrations of scientific literature, as likely lifted from handbills on the street as from an academic monograph in Weigelt's private library.

It is uncertain whether Weigelt showed these works to anyone, or if in fact they were meant to circulate at all. Their production as composites in a darkroom is fairly self-evident; cut-out elements were arranged onto a square surface, subsequently photographed on film negatives, and then printed on photographic paper. The aesthetic decisions in bringing these elements together indicate that Weigelt had some familiarity with black-and-white photographic development processes, such as masking, burning and variable exposure. The collages also present Weigelt's strong sense of combinatorial experimentation, an element further underscored by the application of diverse photo-montage techniques and compositional inventiveness. However, there is no indication of where these collages were crafted, whether Weigelt benefited from any additional specialized assistance, or what was the ultimate purpose behind their making.

Figure 20. Photo-collage attributed to Johannes Weigelt. A crowd scene at a mine location is presided over by Weigelt, seen here with his arm outstretched while pointing out a site to the group. Crushed granular residue is applied to the surface on the top half of the photograph, simulating an explosion. Erhard Voigt is the figure on the upper right-hand corner; he was assistant and colleague to Weigelt both in the Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and later in the Geiseltalmuseum. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

Figure 21. Photo-collage attributed to Johannes Weigelt. The building bearing the sign of the Institute of Geology and Palaeontology was the previous location of the Geiseltalmuseum. The faces of Weigelt's academic staff are pasted onto the bodies of marching German soldiers, including Erhard Voigt (far right). Weigelt's figure looms in the background, the foreboding of war and destruction during his headship of the Geiseltalmuseum revealed starkly in hindsight. Courtesy of ZNS, MLU-HW.

What Weigelt's enigmatic collages do provide is a re-examination of the Geiseltalmuseum as a Leichenfeld in itself – a site of salvaged and commingled remnants. Be it in their organic or their pictorial accumulation, fossilized and printed matter collapse disparate temporal elements, interpreted via archaeological extraction on the one hand and cut-and-paste reinterpretation on the other.Footnote 14 Similarly, the taphonomic processes of fossil creation – sealing and concealing, preserving and exposing – are analogous to the discontinuous history of the Geiseltalmuseum, with its openings and closures, as well as its prominent displays and its unknown findings. The collages and specimens at the Geiseltalmuseum, as well as the uncertainty of their present interpretation when read against Weigelt's academic and political life, offer a reminder that the meaning of a museum collection is never entirely settled, and, as such, cannot be said to fully conclude.

The words ‘collage’ and ‘collection’ stem from the Greek and Latin roots kólla, ‘to glue’, and colligere, ‘to gather.’ In Weigelt's oeuvre, fossils and pasted paper are fragmentary artefacts, both archaic and war-ridden in their disposition towards the viewer. Fascist inclinations, translated unambiguously in graphic and political allusions, do not escape Weigelt's scholarly and creative projects. Yet to understand the Geiseltalmuseum within the larger frame of taphonomy is to consider these ideological imprints as sites of hitherto unexplored connection – compounded layers of evidence related to mass extermination, both within the geological record and as a result of brutal human decimation from genocide and war.