Introduction

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) was originally developed by Marsha Linehan to treat suicidal behaviours and borderline personality disorder (BPD). It conceptualizes emotional dysregulation as stemming from a transaction between an individual’s biological vulnerability and an invalidating environment. The therapy is focused on helping clients to develop emotion regulation, distress tolerance, mindfulness and interpersonal effectiveness skills. Additionally, it aims to strengthen client motivation for change, therapist skills and motivation, and supportiveness of the environment (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). It was designed to be offered via multiple modalities, including group therapy (for skills training) and individual therapy to promote skills generalization and client motivation (Linehan, Reference Linehan2015).

DBT is currently the most commonly used intervention for modifying ineffective patterns of emotional regulation. This therapy has been found to significantly reduce suicidal and self-injurious behaviours, psychiatric hospitalizations, depression, and drop-out rates among participants in comparison with control groups (Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon and Heard1991; Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Heard and Armstrong1993; Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Comtois, Murray, Brown, Gallop, Heard, Korslund, Tutek, Reynolds and Lindenboim2006; Lynch et al., Reference Lynch, Trost, Salsman and Linehan2007). DBT interventions specifically target emotional regulation, a hypothesized mechanism that explains how individuals modulate and adapt emotional responses in a context-sensitive manner (Papa and Epstein, Reference Papa, Epstein, Hayes and Hofmann2018). Consistent with this, neuroimaging findings have shown that, following DBT, clients show attenuated hyperarousal in the amygdala and anterior cingulate and greater coupling between limbic and frontal regions (Niedtfeld et al., Reference Niedtfeld, Schmitt, Winter, Bohus, Schmahl and Herpertz2017; Schmitt et al., Reference Schmitt, Winter, Niedtfeld, Herpertz and Schmahl2016). Most DBT techniques can be applied to any strong emotion, although shame and anger may be particularly heightened in BPD and underpin the impulsivity and self-injury that often characterize this presentation (Rüsch et al., Reference Rüsch, Lieb, Göttler, Hermann, Schramm, Richter, Jacob, Corrigan and Bohus2007; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Wright, Beeney, Lazarus, Pilkonis and Stepp2017).

Whilst DBT was originally designed as a 12-month program combining the multiple therapy modes, more recent studies have demonstrated its efficacy as a 6-month program (Pasieczny and Connor, Reference Pasieczny and Connor2011; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Brodsky, Nelson and Dulit2007). In an attempt to make the treatment more cost-effective and accessible, even shorter programs using only the skills-group component have been evaluated. For example, Heerebrand et al. (Reference Heerebrand, Bray, Ulbrich, Roberts and Edwards2021) found significant reductions in BPD symptoms and depression following an 18-week DBT skills group compared with waitlist. Keng et al. (Reference Keng, Mohd Salleh Sahimi, Chan, Woon, Eu, Sim and Wong2021) found that a 14-week program produced significant reductions in depression and emotion-regulation in adults with BPD, and non-significant reductions in self-harm, suicidal ideation and anxiety. Zapolski and Smith (Reference Zapolski and Smith2017) found mixed results in a brief (9-week) DBT skills group for adolescents, finding a significant decrease in intent to engage in risky behaviours, but no significant changes in negative mood. However, a limitation of all these studies is that they cannot separate the non-specific effects of psychotherapy (e.g. group cohesion), from the specific effects of learning DBT skills.

Few studies to date have compared DBT with a control group. Soler et al. (Reference Soler, Pascual, Tiana, Cebrià, Barrachina, Campins and Pérez2009) compared 3 months of group DBT with a control group and found that the former had lower drop-out and greater improvements in depression, anxiety, anger and affect instability. Another study (Safer et al., Reference Safer, Robinson and Jo2010) compared DBT with control group sessions, but specifically for binge eating. Both conditions produced improvements in binge eating but not in emotional regulation, leading the authors to conclude that DBT skills did not offer a benefit to this client group over and above non-specific group effects. Overall, more research is warranted that teases apart the specific effects of DBT skills groups from non-specific effects.

DBT in Latin America

Linehan’s (Reference Linehan1993) approach has obtained significant attention in Latin America, offering an integrative approach to the multiple variables that play a role in important issues such as suicidal behavior (Córdova et al., Reference Córdova, Rosales and Montufa2015). The efforts being made regarding DBT implementation and development in the region are illustrated by studies with families implementing group DBT interventions (Regalado et al., Reference Regalado, Pechon, Stoewsand and Gagliesi2011) and published clinical guidelines for DBT in Spanish (Boggiano and Gagliesi, Reference Boggiano and Gagliesi2018; Lencioni and Gagliesi, Reference Lencioni and Gagliesi2008).

Guerra-Báez et al. (Reference Guerra-Báez, Magaly, David, León-Durán, Olaya-Riascos and Puentes-Ramírez2019) evaluated the efficacy of a DBT-based intervention with a young population in Colombia who presented self-injurious behaviours without suicidal intent, finding significant differences in the pre- and post-tests in emotion regulation, anxiety and depression, but not in self-injury. Nonetheless, evidence for DBT acceptability and effectiveness in this region is lacking.

As with any heterogenous group, mental health needs of Latinx clients vary widely, but common stressors in this region are financial instability and poverty, domestic violence and high internal migration, combined with scarcity of mental health services and stigma about accessing these services (Alarcón, Reference Alarcón2003). Particularly relevant to DBT, the cultural tendency to see mental health difficulties as shameful may contribute to the ‘invalidating environment’, which DBT’s biosocial model identifies as a key cause of emotional dysregulation (Kirmayer and Minas, Reference Kirmayer and Minas2000).

Online therapy: acceptability and effectiveness

Telepsychology (the delivery of psychological services with technology) has been promoted for some time as a promising complement or alternative to in-person support. Whilst telepsychology incorporates a wide range of interventions, for the purposes of this study we focus on group therapy that mirrors in-person group therapy as closely as possible: that is, fully facilitated by trained therapists and involving synchronous interaction between participants and facilitators via videocall.

Group psychotherapy via video conferencing became immediately widespread following the outbreak of COVID-19. It offers a practical solution to common barriers to therapy, such as long travel times to sessions, travel expenses, and so forth (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Sequeira, McCord and Garney2016). However, challenges have also been reported, including greater fears about privacy, reduced engagement, distraction for clients, frustration (Cooney et al., Reference Cooney, Walton and Gonzalez2022; Kozlowski and Holmes, Reference Kozlowski and Holmes2014), and disruption of interpersonal processes such as group cohesion (Ben-David et al., Reference Ben-David, Ickeson and Kaye-Tzadok2021; Ramzan et al., Reference Ramzan, Dixey and Morris2022).

Regarding virtual DBT specifically, several commentaries and qualitative articles have been published focusing on group facilitators’ perceptions of challenges and lessons learned in the transition to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic (Hyland et al., Reference Hyland, McDonald, Verzijl, Faraci, Calixte-Civil, Gorey and Verona2021; Landes et al., Reference Landes, Pitcock, Harned, Connolly, Meyers and Oliver2021; Zalewski et al., Reference Zalewski, Walton, Rizvi, White, Martin, O’Brien and Dimeff2021). Logistical challenges included establishing methods for safe and confidential document-sharing, establishing methods for collaboratively doing exercises such as chain analyses in individual therapy, and establishing protocols should a client make a suicide threat and then disconnect from the session. Facilitators tended to report that the skills groups were the most difficult modality to provide via telehealth (Landes et al., Reference Landes, Pitcock, Harned, Connolly, Meyers and Oliver2021). Zalewski et al. (Reference Zalewski, Walton, Rizvi, White, Martin, O’Brien and Dimeff2021) highlight the need to recognize therapy-interfering behaviours specific to telehealth contexts.

Some studies have shown that online group psychotherapy can have similar results to in-person group therapy, both in terms of symptom change (Ellis et al., Reference Ellis, Campbell, Sethi and O’Dea2011; Khatri et al., Reference Khatri, Marziali, Tchernikov and Shepherd2014), and group bonding and cohesiveness (Banbury et al., Reference Banbury, Nancarrow, Dart, Gray and Parkinson2018). Unfortunately, the literature for internet-delivered DBT is scarce, despite the proliferation of this modality following COVID-19. To our knowledge, only one study has compared online versus in-person group DBT (López-Bueno et al., Reference López-Bueno, Calatayud, Ezzatvar, Casajús, Smith, Andersen and Lopez-Sanchez2020). Findings indicated that the in-person group had greater group cohesion but had lower attendance and was perceived to be less convenient. However, the study did not evaluate changes in participants’ symptoms. Additionally, the group was predominantly composed of people with depression (with symptom severity not reported), so it is hard to know whether results can be generalized to populations that typically receive DBT. Thus, this points to a clear need for more outcome data for internet-delivered DBT, as has been highlighted previously (Zalewski et al., Reference Zalewski, Walton, Rizvi, White, Martin, O’Brien and Dimeff2021).

The present study aimed to explore satisfaction, retention, and effects of an internet-delivered DBT-based intervention added to individual online sessions, given the lack of outcome data in this modality worldwide. In recognition that any group experience may have a powerful therapeutic benefit, particularly under quarantine conditions, the present study aimed to isolate the effects of group DBT skills training from non-specific group effects. The primary outcome was the emotional regulation process (the putative process of change of DBT) and secondary outcomes were anxiety and depression. We expected that participants would show some symptom improvement during blocks of placebo sessions, but that they would show more symptom improvement during blocks of group DBT sessions.

Method

Participants

One hundred and thirty-three people were recruited at the university-based therapy clinic. The screening questionnaire was used to check study eligibility. The exclusion criteria were (a) the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), defined as scoring >11 in the Multidimensional Emotional Disorder Inventory sub-scale for traumatic re-experiencing (Rosellini and Brown, Reference Rosellini and Brown2019), (b) positive screen for bulimia or binge eating as measured by the PHQ, (c) bipolar disorder, evaluated in a clinical interview, and (d) previous suicide attempts within 3 months, current plan, or identified method. Individuals excluded were referred to specialized individual services in the center for PTSD, anxiety, suicidal behaviours, and depression problems or mental health providers outside of the center.

Inclusion criteria were (a) scoring >44 on the General Emotional Dysregulation Measure (GEDM, see ‘Measures’ section below); and (b) willingness to participate in a group session every week. The screening was complemented with 108 people who had an individual semi-structured interview conducted by clinical psychology master’s students to check for validity of questionnaire results. Of the 12 who met the criteria, all were offered treatment but six did not begin due to difficulties with connectivity, time limitations, or social barriers to accessing treatment. The remaining six began treatment, but one dropped out at session 2 due to work schedule. The present article considers data from the five participants who completed the 4-month intervention. They were three females and two males with an average age of 23.6 years and lived in a major urban city in Colombia.

Measures

The Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale (DERS-SF) is a 15-item questionnaire, rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The Colombian version was administered, which has good reliability according to Cronbach’s alpha (α=0.89; Muñoz-Martínez et al., Reference Muñoz-Martínez, Vargas and Hoyos-González2016). Although the Colombian version of the DERS-SF produced two distinct factors, (a) awareness (1-item) and (b) strategies (14-items), only the Strategies subscale (M=30.82; SD=9.48) was administered in this study. DERS Strategies total scores range from 14 to 70 points, with high scores indicating considerable difficulties engaging in emotion regulation strategies. Whilst there is no accepted clinical cut-off for interpreting the DERS-SF, a previous study found a mean item score of 2.00 (SD=0.61) in a non-clinical student sample (Kaufman et al., Reference Kaufman, Xia, Fosco, Yaptangco, Skidmore and Crowell2015), which would translate to a total score of 28 for DERS Strategies.

The General Emotional Dysregulation Measure (GEDM; Newhill et al., Reference Newhill, Mulvey and Pilkonis2004) is a 13-item questionnaire designed to measure general levels of emotional dysregulation (especially negative affect), as well as erratic and unpredictable behaviours. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 to 5, producing possible scores from 13 to 65, with high scores signifying higher levels of emotional arousal and dysregulation. The original validation produced an alpha of 0.82. A forward-backward translation to Spanish with very good reliability according to Cronbach’s alpha (α=0.94) was implemented in this study by bilingual speakers (Gómez-Maquet et al., in preparation).

The Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS; Norman et al., Reference Norman, Cissell, Means-Christensen and Stein2006) is a 5-item questionnaire designed to measure impairment and symptoms associated with different anxiety disorders. Responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 to 4 points, producing possible scores from 0 to 20. Scores higher than 8 are regarded as clinically relevant. The original validation produced an alpha of 0.80. A Colombian Spanish version (Silva and Unda, Reference Silva and Unda2015) was implemented in this study that has good reliability according to Cronbach’s alpha (α=0.92).

The Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale (ODSIS; Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Gallagher, Carl and Barlow2014) is a 5-item questionnaire designed for use across mood disorders and with subthreshold depressive symptoms. Continuous measures are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 to 4 points, producing possible scores from 0 to 20, scores higher than 8 are taken as clinically relevant. High scores denote higher levels of symptoms and impairment related to depression. The original validation produced a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 in the community sample. A Colombian Spanish version (Silva and Unda, Reference Silva and Unda2015) was implemented in this study that has good reliability according to Cronbach’s alpha (α=0.89).

The Eating disorders subscale of the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ; Spanish version) (Montalbán et al., Reference Montalbán, Comas and García-García2010) was designed as an eating disorder screen for primary care settings. It contains eight dichotomous ‘yes/no’ items enquiring about sense of control regarding eating, portion size, purging, fasting, and excessively exercising to lose weight.

The University of Washington Risk Assessment and Management Protocol (UWRAMP; Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Comtois and Ward-Ciesielski2012) is a structured interview developed to assess presence of high-risk suicidal behaviours and provide some treatment recommendations. A forward-backward translation to Spanish was utilized in the eligibility assessment. People reporting an imminent suicide risk on the UWRAM were referred to other providers.

Aiming to assess group cohesion, which is the equivalent of working alliance but for group therapy, the following two items from the Spanish version of Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Andrade-Gonzalez and Fernandez-Liria, Reference Andrade-González and Fernández-Liria2015) were adapted to measure group members’ alliance: 14 (‘The objectives of the session were important to me’ – measuring goals), and 4 (‘The session provided me with new insights into my problem’ – measuring tasks). As no items of the WAI were deemed to measure bond in group sessions, we used the first item of the Session Rating Scale (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Miller, Sparks, Claud, Reynolds, Brown and Johnson2003) that states: ‘I have felt heard, understood, and respected by the group therapists’. Following the WAI, all items were rated from 1 (never) to 7 (always), with high scores meaning a higher perception of group cohesion.

Credibility was measured with the following three items created for this study that assessed trust, credibility, and the possibility of recommending the treatment received: (a) does the therapy offered to you seem coherent?; (b) do you think this treatment will be successful in reducing your symptoms?; and (c) do you feel confident in recommending this treatment to a friend who experiences similar problems? Responses were scored on a 9-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 9 (totally), producing possible scores from 3 to 27, with high scores representing a higher perception of credibility.

Design and procedure

A withdrawal A1-B1-A2-B2 experimental single-case design was conducted to evaluate whether the DBT skills group boosted the effect of individual therapy on participants reporting higher levels of emotional dysregulation. Experimental single-case designs (SCD; i.e. time-series methodology) are characterized by repeated assessments of behaviours and their contexts across time. Ongoing measurement allows for identifying possible sources of influence of dependent variables (e.g. measurement errors, extraneous variability) other than the independent variable. In addition, most SCDs use a baseline phase (e.g. placebo phase) in which behaviours are measured as they happen under no-treatment conditions, functioning as a control phase to which intervention phases are compared (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Barlow and Nelson-Gray1999). That is, in SCD the individuals act as their own control because the ongoing measurement allows one to compare behavioural patterns with and without treatment, which is similar to group-design comparisons between the control group (no-treatment) and the experimental group (treatment). Repeated assessment of behaviours and baseline comparisons make SCD a robust methodology with high internal experimental control as they provide information on the sources that may influence behaviour and compare data changes on treatment and no-treatment conditions (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Barlow and Nelson-Gray1999).

Participants attended 50-minute sessions of individual DBT every other week across the study, whilst group sessions were implemented weekly. Within the placebo phase (A), group sessions consisted of a 90-minute session on mental health literacy, whilst during the intervention phase (B), group sessions lasted two hours and involved DBT skills training and homework review. Participants were invited to contact hotlines in the area should they require support in a crisis, as the center did not have the capacity to offer telephone support.

Each participant was assessed at baseline, at weekly sessions, at the end of treatment, and at 1-month follow-up. The eligibility assessment consisted of PHQ-15, the UWRAMP, and GEDM. The latter was also administered at post-test and 1-month follow-up. The weekly battery included: OASIS, ODSIS, DERS, and Group cohesion questions. Credibility was measured at the end of each research phase with the aim of evaluating how much participants trusted the strategies offered at each phase.

Description of individual sessions

The first four individual sessions were dedicated to establishing a therapeutic relationship, establishing a crisis plan, discussing DBT values, reviewing biosocial theory, clarifying the DBT treatment modalities offered in the center, and identifying treatment goals and the current treatment stage for each participant. Each session started by reviewing the following DBT hierarchy in order to establish therapy targets: (a) life-threatening behaviours, (b) therapy-interfering behaviours, and (c) quality of life interfering behaviours. Clients were asked to complete a diary card weekly, which was subsequently reviewed by the therapist and client to identify clinical targets on which they conducted chain analyses, solution analyses, and skill practice.

Description of group sessions

Each session began with participants completing continuous measures of depression symptoms, anxiety indicators, and emotion regulation difficulties. Later, group facilitators conducted a mindfulness exercise (only in DBT sessions) and reviewed homework. When participants had not completed homework, a missing links analysis was conducted (Linehan, Reference Linehan2015). Afterwards, group facilitators introduced the session topic or skill depending on the treatment phase (see Table 1). Each of the group DBT sessions covered one of the four skills modules, with content drawn from the DBT manual (Linehan, Reference Linehan2015), particularly those skills that the authors perceived as most helpful in their previous clinical practice. At the end of the session, participants received a Qualtrics link to evaluate their perception of group cohesion.

Table 1. DBT and placebo groups sessions by topic

Manual development, therapist training, and supervision provision

Based on the second edition of the DBT Skills Training Handout and Worksheets (Linehan, Reference Linehan2015) and the Skills Training Handouts for DBT® Skills Manual for Adolescents (Rathus and Miller, Reference Rathus and Miller2015) a brief DBT manual was developed. This manual was adapted by A.M.-M. and Y.G., both clinical psychologists with PhDs with at least four years of experience implementing DBT with adults in different contexts.

Therapists for both group and individual DBT modalities were clinical psychology masters’ students, with at least 1 year of supervised practice prior to the study start. Therapists were given training in DBT principles and group therapy provision in advance. Training and weekly group supervision was provided to therapists by a clinical psychologist with specialist training in DBT and with over 5 years of experience delivering this. Individual DBT sessions for group clients were conducted by independent therapists. They were also supervised by the group supervisor and A.M.-M. DBT consultations were also conducted fortnightly with both supervisors and all therapists.

Placebo group sessions were designed by Y.G. and I.N., whom both held Doctorates in Clinical Psychology and had at least 8 years of therapy experience. Activities and content of placebo sessions were based on brainstorming with students and colleagues and aimed to keep group cohesion while maintaining high credibility for participants.

Data analysis

Repeated measures from the DERS, ODSIS and OASIS of group participants were merged into a group-mean score. Based on this, visual inspection of level, variability and trend was performed on the group across phases (Manolov and Moeyaert, Reference Manolov and Moeyaert2017). In addition, a Nonoverlap of All Pairs analysis (NAP; Parker and Vannest, Reference Parker and Vannest2009) was run to assess within-group effect size using Pustejovsky and Swan’s (Reference Pustejovsky and Swan2018) web calculator. NAP is conceptualized as the percentage of all pairwise comparisons across the baseline (phase A) and intervention (phase B) that show improvement from the baseline phase to the intervention phase. An average NAP for each pair (A1 versus B1, and A2 versus B2) was calculated to establish a global effect size for the DBT group treatment. Parker and Vannest (Reference Parker and Vannest2009) provided the following standards to interpret NAP effect sizes based on the analysis performed with simple phase change and complex phase SCDs: weak (0–0.65), medium (0.66–0.92), and large (0.93–1.0).

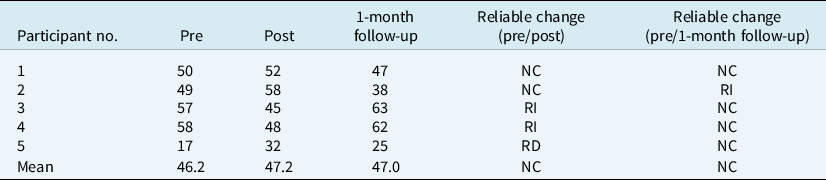

As the GEDM was only applied at three time points, this was analysed differently. Specifically, the reliable change index (RCI; Jacobson and Truax Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) was used to compare pre-test to post-test, and pre-test to 1-month follow-up data. The RCI specifies the amount of change a client must show on a specific psychometric instrument between measurement occasions for that change to be reliable (i.e. larger than that reasonably expected due to measurement error alone). This is a recommended approach for small-N studies (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2011). The RCI is calculated by 1.96 times the standard error of change, which is based upon each measure’s internal consistency and standard deviation. Values were taken from the dataset of the 86 participants who completed the screening for the present study (Gómez-Maquet et al., in preparation; α=0.94, M=45.4, SD=12.5), which produced an RCI of 8.49.

Results

Results are presented in two sections. First, a within-group visual inspection and a non-overlap analysis of all pairs (NAP) to assess effect sizes of average group scores in emotional regulation difficulties (DERS), depressed mood (ODSIS) and anxiety symptoms (OASIS) will be described. As these instruments were administered before starting group sessions, scores were graphed starting from week zero (0) on the x-axis. Group cohesion was measured at the end of each group session; thus, the first score was graphed at week 1 on the x-axis. Second, we present whether each participant showed a reliable change from pre-test to post-test, and pre-test to follow-up on the GEDM.

Visual inspection shows differences in emotional dysregulation scores across phases (Fig. 1). During the first placebo phase (A1), dysregulation showed a slightly increasing trend (i.e. deterioration). It should be noted that this occurred even though participants were attending individual DBT sessions every two weeks, in parallel to all group sessions. In comparison, when the DBT skills group (B1) was implemented, a sudden reduction in level was observed (i.e. improvement), with scores moving from 54 points in the last data point at A1 to 50.2 at the beginning of B1, which represents a decrease of more than two standard deviations. In A2, DERS scores remained stable in terms of level and trend. When group DBT was reintroduced (B2), a meaningful reduction in level was observed compared with mean levels at A1 and A2. NAP analysis indicated large effect sizes for the A1-B1 pair (NAP=1.00, SE=0.05; 95% CI: [1.00–1.00]), as well as for the A2-B2 pair (NAP=1.00, SE=0.08; 95% CI: [1.00–1.00]).

Figure 1. Emotional dysregulation (DERS) interacting with group cohesion items.

Group cohesion measured by the WAI and Session Rating Scale began at least at 5.9 points in session 1, and subsequently, when treatment was introduced at B1 reaches a ceiling effect that remain across research phases (Fig. 1). Similarly, credibility was evaluated as high by the group throughout the study (ranging from 8.0 to 8.4 of a possible of 9).

Depressed mood (ODSIS) and anxiety (OASIS) had different patterns compared with emotional dysregulation (Fig. 2). Visual inspection showed a slight difference in level by the end of A1 phase in mood symptoms, but neither the trend nor level of anxiety scores changed when shifting from A1 to B1. However, when introducing the second placebo phase (A2) both symptom measures steeply decreased by more than two standard deviations from the A1 mean. While both ODSIS and OASIS scores again fell to a lower level when introducing the DBT-skills group for the second time (B2), they remained stable (flat) over this last phase. NAP indexes for depressed mood showed that the comparison between A1 and B1 produced a medium effect size (NAP=0.9, SE=0.1; 95% CI: [0.50–0.99]) whilst the A2-B2 comparison produced a large effect size (NAP=1.0, SE=0.08; 95% CI: [1.0–1.0]). NAP indexes for anxiety indicated a weak effect size in the A1-B1 pair (NAP=0.61, SE=0.21; 95% CI: [0.26–0.86]), and a moderate effect size when comparing the A2-B2 pair (NAP=0.83, SE=0.17; 95% CI: [0.39–0.97]).

Figure 2. Scores from the Overall Depression Severity and Impairment Scale (ODSIS) and the Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) across the research.

Reliable change

The mean of the general emotional dysregulation measure (GEDM) for the group was similar at pre-treatment (46.2), post-treatment (47.2), and 1-month follow-up (47.0), showing no reliable change between time points, based on the RCI of 8.49 calculated for this study (see Method section).

Table 2 presents individual participants’ raw GEDM scores at pre-test, post-test, and 1-month follow-up, and whether they achieved reliable change. Two out of five participants showed a reliable improvement from pre-test to post-test although two showed no change and one showed reliable deterioration. Change was largely not maintained at 1-month follow-up, with four showing no reliable change and one reporting a reliable improvement.

Table 2. Participant raw scores on emotional regulation on the GEDM, and whether clients showed reliable change (>8.49 points up or down)

NC, no change; RI, reliable improvement; RD, reliable deterioration.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the additive effect of online group DBT to individual sessions in comparison with online group placebo, principally for emotional dysregulation (measured by the DERS) but also for depression and anxiety symptoms, in a Latinx sample. Emotional dysregulation showed greater improvements in the group DBT phases compared with group placebo sessions. This supports the idea (a) group DBT offers something more than generic group effects (which the placebo phase controls for), (b) the skills development content in group DBT is important for clients, and effective when administered online (Gutteling et al., Reference Gutteling, Montagne, Nijs and van den Bosch2012), and (c) DBT procedures addressed primarily emotional regulation processes (Barney et al., Reference Barney, Murray, Manasse, Dochat and Juarascio2019; Goodman et al., Reference Goodman, Carpenter, Tang, Goldstein, Avedon, Fernandez and Hazlett2014). Two things are especially notable: (a) a marked difference in clients’ emotional dysregulation when receiving individual plus group DBT sessions but not when group placebo was added to individual therapy and (b) changes in emotional dysregulation associated with a brief 8-week DBT online group compared with the usual length of group DBT (Heerebrand et al., Reference Heerebrand, Bray, Ulbrich, Roberts and Edwards2021; Keng et al., Reference Keng, Mohd Salleh Sahimi, Chan, Woon, Eu, Sim and Wong2021; Safer et al., Reference Safer, Robinson and Jo2010).

Contrary to expectations, generalized emotional dysregulation (as measured by the GEDM) did not show a reliable change at a group level, either pre-test to post-test, or pre-test to follow-up. Examining individual scores, reliable change can be observed in only two participants post-treatment and one at 1-month follow-up. One explanation is that a larger treatment dose may be necessary to ensure lasting change in all the areas measured by the GEDM such as changing invalidating environments, approaching emotions in the present moment with flexibility, and stabilizing longstanding erratic and unpredictable behaviours (Newhill et al., Reference Newhill, Mulvey and Pilkonis2004). Eight DBT group and individual sessions are a relatively small dose, given that the evidence base for this therapy is based upon the standard program with weekly individual and group therapy over 12 months (Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon and Heard1991; Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Schmidt, Dimeff, Craft, Kanter and Comtois1999) or more recently, a briefer 6-month program (McMain et al., Reference McMain, Chapman, Kuo, Dixon-Gordon, Guimond, Labrish, Isaranuwatchai and Streiner2022; Pasieczny and Connor, Reference Pasieczny and Connor2011; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Brodsky, Nelson and Dulit2007).

Anxiety symptom reduction was not directly associated with DBT group sessions. Changes in anxiety indicators show a drop in symptoms occurring with the introduction of the second placebo phase, but not during treatment phases. Although mood symptoms slightly decrease when the first DBT group sessions were introduced, marked changes were observed in the second placebo phase. Firstly, this may reflect that DBT skills sessions predominantly target emotion regulation processes rather than anxiety and depression per se. Indeed, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of DBT for adults with BPD showed it to be no better than treatment as usual (TAU) for depression (Panos et al., Reference Panos, Jackson, Hasan and Panos2014). Little evidence exists for the impact of DBT on anxiety. One uncontrolled study found that a DBT-informed intervention improved both anxiety and depression in a sample of 38 adults, but the program was intensive (20+ hours a week) and the sample included some individuals with only depression and anxiety, not emotional dysregulation (Lothes et al., Reference Lothes, Mochrie and St John2014).

Secondly, the larger effect on depression and anxiety seen during the placebo phase might reflect the impact of individual sessions, plus the topics chosen for placebo groups which included (a) myth-busting about mental health treatment, (b) recognizing the role of social support in mental health, (c) healthy habits, and (d) ways to reframe failure. Although care was taken to promote unguided group discussion rather than psychoeducation, clients may nonetheless have taken away useful lessons from these discussions. Indeed, it is likely that reflection on social support and healthy habits might promote self-care and engagement in health-promoting behaviours that are related to symptom reduction in anxiety and depression (Gariepy et al., Reference Gariepy, Honkaniemi and Quesnel-Vallee2016; Gómez-Gómez et al., Reference Gómez-Gómez, Bellón, Resurrección, Cuijpers, Moreno-Peral, Rigabert and Motrico2020; Hashimoto et al., Reference Hashimoto, Nishiyama, Nakae and Noda2001; López-Bueno et al., Reference López-Bueno, Calatayud, Ezzatvar, Casajús, Smith, Andersen and Lopez-Sanchez2020).

Group cohesion was high throughout the treatment and was not different between placebo versus treatment, suggesting that any difference in the scores of one module versus another was not due to improvements in cohesion. These findings support our hypothesis that emotional dysregulation lessened due to skills taught in DBT group sessions rather than simply group cohesion effects, to which research in group therapy has attributed a good amount of responsibility (Clough et al., Reference Clough, Spriggens, Stainer and Casey2021).

Retention was relatively high, in line with studies showing generally high acceptance of DBT and the further reduction of drop-out when offered online (López-Bueno et al., Reference López-Bueno, Calatayud, Ezzatvar, Casajús, Smith, Andersen and Lopez-Sanchez2020). These findings support the utility of DBT in online formats, for which empirical evidence is scarce (van Leeuwen et al., Reference van Leeuwen, Sinnaeve, Witteveen, Van Daele, Ossewaarde, Egger and van den Bosch2021).

Limitations

Individual DBT sessions were offered throughout the process, in order to monitor and manage risk. This might have minimized differences in effect sizes between DBT-group treatment and placebo sessions. Additionally, placebo sessions may have been overly effective and minimized the effect observed for treatment sessions. Placebo sessions included homework and homework revision, which was done to increase credibility and minimize perceived differences between session types for clients. However, in hindsight, this may have unintentionally taught skills to participants by therapists reviewing homework assignments (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Simons and Thase1999; Scheel et al., Reference Scheel, Hanson and Razzhavaikina2004).

Although a manualized protocol was used to ensure fidelity to DBT, the modest experience level of therapists in the present study (as detailed previously) means that caution is warranted in generalizing findings to settings with more experienced therapists. Nonetheless, the importance of studying real-world contexts has also been recognized, since outcomes for psychotherapy trials, including DBT, are less effective in the real world (Feigenbaum et al., Reference Feigenbaum, Fonagy, Pilling, Jones, Wildgoose and Bebbington2012). Thus, the fact that we found some promising findings in emotional dysregulation and mood symptoms despite a brief intervention and without extensively trained therapists attests to the potential of this mode of therapy.

The withdrawal design conducted in this study has a verification phase (A2) that allows comparing active treatment components with placebo. However, withdrawal designs can lose power to verify effects when interventions are skills-focused, as in the present study, due to contamination between phases (Byiers et al., Reference Byiers, Reichle and Symons2012). It is likely that learning effects occurred when DBT skills were taught and hindered the design capacity of clearly identifying the independent effects of group DBT. While emotional dysregulation remained stable when withdrawing DBT group sessions, indicating that placebos were not responsible for the change in this variable, mood and anxiety symptoms did not show such a pattern. Future studies could use multiple baseline designs that do not require a withdrawal phase, allowing comparison of treatment among participants and implementing longer intervention sessions (Byiers et al., Reference Byiers, Reichle and Symons2012). While experimental single-case designs are a powerful tool for evaluating treatment effects with high experimental control, they lack enough power to generalize results to a broader population (Hayes et al., Reference Hayes, Barlow and Nelson-Gray1999). Replications and studies with group designs would be also useful to evaluate effectiveness and outcomes in the general population.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that online group DBT plus biweekly individual DBT sessions are acceptable for out-patient Latinx clients. While research in online formats is scarce, this study showed that a combination of a low individual dose of individual DBT sessions plus group DBT is a feasible approach for changing emotional dysregulation processes and mood symptoms. In addition, the finding that improvement in this study was not due to unspecific variables like cohesion provides preliminary information on potential mechanisms of change in DBT. This type of treatment modality may be effective for reducing emotional dysregulation, but future studies should explore the effects of longer or more intensive treatments over longstanding erratic and unpredictable behaviours often seen in chronic dysregulation.

Data availability statement

Data are available at the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/pwb4a/

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank master’s students in clinical and health psychology at the University of the Andes who provided individual and group therapy in this study. We also want to thank to Alexandra Avila for providing supervision to therapists in this research. Finally, we thank the Social Science Faculty at the University of the Andes for the funding provided through the “Bolsa de Investigaciones”.

Author contributions

Amanda Muñoz-Martínez: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Resources (equal), Software (equal), Supervision (equal), Visualization (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Yvonne Gómez: Conceptualization (equal), Investigation (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Iona Naismith: Conceptualization (equal), Investigation (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Daniela González Rodriguez: Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Software (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval by the local IRB at the Universidad de los Andes was obtained before starting this research (approval no. 1624). This study was conducted in accordance with the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki and APA guidelines. All participants granted informed consent and gave permission for publication upon anonymizing their information, in order to protect their identities.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.