Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 August 2017

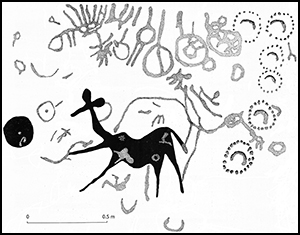

Although the rock art of southern Africa is overwhelmingly concerned with ritual, there are few depictions of the initiation rites so important to hunter-gatherer identity. This study presents the first definitive evidence of women's initiation based on evidence from rock art and archaeological features at the site of /Ui-//aes in Namibia. The evidence reveals multiple links between initiation, women's work in gathering wild grass seed, and the importance of the female kudu as a metaphor of positive social values. These links show that the beliefs underlying ritual practice also form part of everyday subsistence activity, extending the same precepts from mundane artefacts such as grindstones, to the habits of desert antelope.