Introduction

In Africa, as elsewhere in the world, the discovery of subterranean pools of hydrocarbons for which extraction is commercially viable is transformative.Footnote 1 Earnings from oil production finance social sector spending (education, health, and employment-generating investments) and essential services and related businesses. Simply put, oil is wealth. However, any discussion of oil calls for a nuanced approach. Following the discovery, the oil industry attracts all kinds of actors including international companies, local entrepreneurs, opportunistic authorities, honest politicians, and, sadly, unscrupulous individuals.

Oil, a powerful African studies keyword, is no less a metonym for a cluster of terms in the African studies literature. It is a word of diverse meanings that sparks polemical writings. Some use petroleum as a causal agent that thrusts formerly low-income countries into the highly competitive neoliberal world economy. Another influential usage is the oil curse/blessing binary. This debate is a powerful polemic that has shaped many discussions and analyses. Viewed as a curse, petroleum causes dysfunctional behavior and real problems. However, increased revenues just as certainly result in concrete improvements. How one balances the ledger determines where one lands in the curse/blessing debate. Indeed, these debates, among others, highlight how different usages of the term characterize an industry that is increasingly omnipresent on the continent.

In 2020, approximately thirty African countries were exporting hydrocarbons. Here I focus on four producers and exporters—Angola, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, and Nigeria—and examine the different oil terminologies present in diverse disciplinary and interdisciplinary studies, particularly interpretive political science, macroeconomics, anthropology, and sociology. My goal is to animate a conversation about how various disciplines discuss specific terms and concepts related to petroleum production in Africa. Because so many scholars debate the variable impact of hydrocarbons, much of the writing is in disciplinary silos. Some scholars appear unaware of contributions from other fields; they use terms and concepts that reflect their own disciplinary epistemologies and fail to connect to other fields. Research on petroleum requires interdisciplinarity.

Hence, I assemble the oil keyword as a composite from six subordinate terms or concepts which are presented in six sections. After a brief introduction to the four country case studies, I discuss the concept of resource revenue management. I note how corporate and political actors negotiate contracts that include local content requirements (LCRs); oil companies agree to invest in infrastructure, social sector expenditures, and training (Ovadia Reference Ovadia2014; Ovadia Reference Ovadia2016b; Hilson & Ovadia Reference Hilson and Ovadia2020). Fiscal regimes, a technical term from the economic development literature, denotes the contractual arrangements that structure the petroleum sector. I then consider “oil” as a metaphor for energy, energy justice, modernity, and neoliberalism. These terms inform diverse studies of oil exporting countries. The third discussion analyzes the resource curse/blessing dichotomy debated in the political science/political economy literature. Whereas the oil curse thesis presents oil as a cause of lower rates of economic growth, dictatorship, gender inequalities, violent war, and environmental destruction, the blessing thesis sees oil as wealth that can be used to improve public services, promote gender equality, contribute to political efficacy, and embed democratic practices. The next section analyzes how oil production has caused shocking environmental destruction. Companies, often negligently, fail to maintain security or the integrity of the oil pipelines, leading to spills that deepen poverty, unemployment, and injustice in oil producing regions. I then turn to oil as community, and in particular how people respond to the displacements wrought by oil production. Members of local communities compose an oil complex of actors that interact in the value chain. In the final section, I turn to corruption. Although corruption is evident in the theft of billions of dollars by dishonest officials and their collusive partners in oil companies, its occurrence is most evident in countries where agencies of control were nonexistent when hydrocarbon production began.

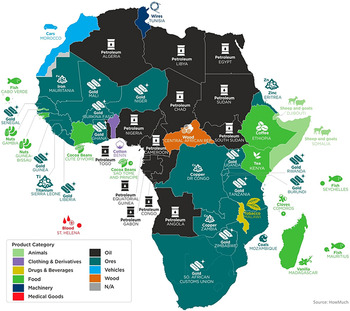

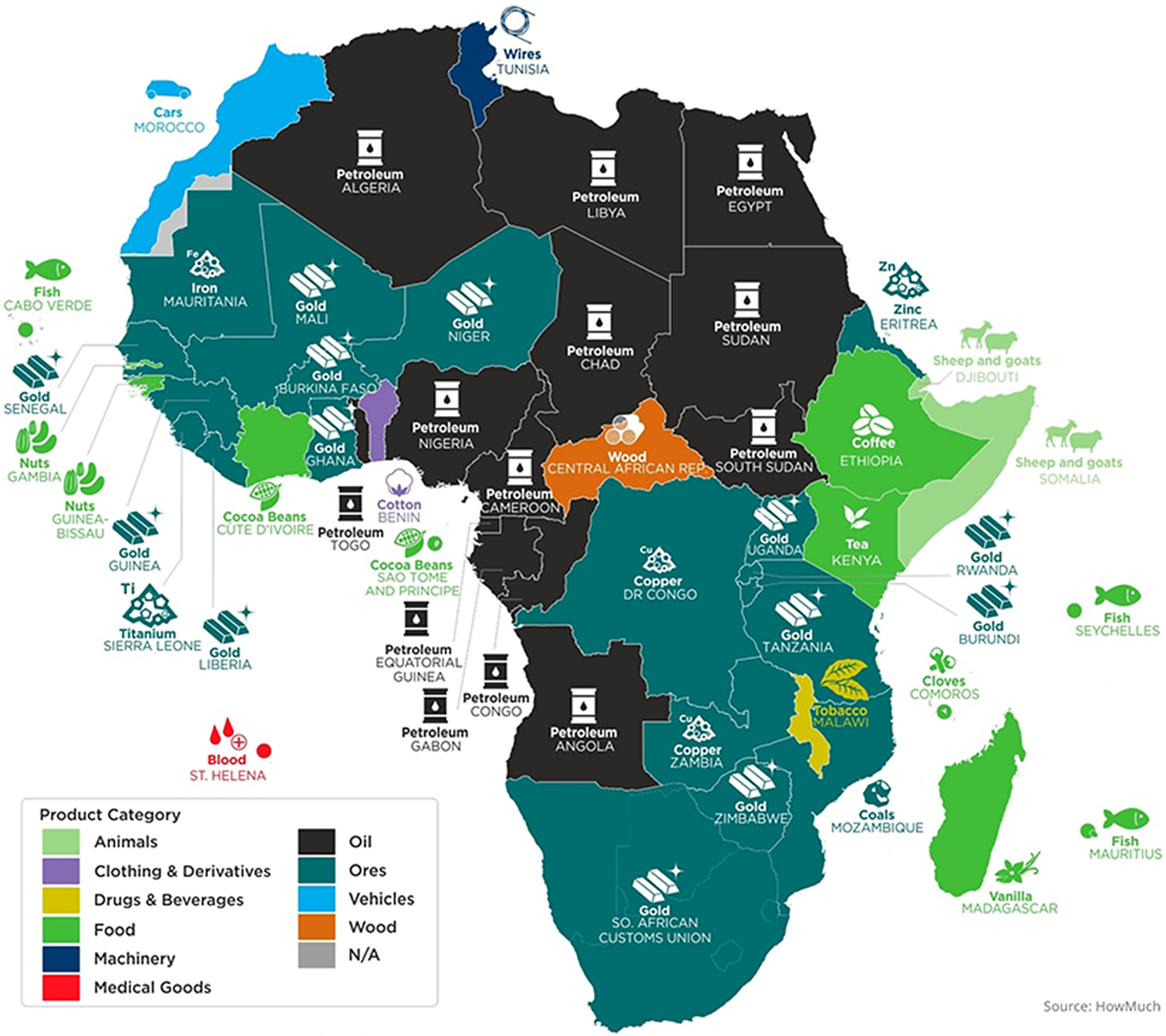

Map 1 displays the extraordinary wealth found on the African continent. Although it does show the hydrocarbons in the four countries discussed in this essay, it neglects the hydrocarbons in Ghana, South Africa, and Uganda and natural gas in Tanzania and Mozambique. This omission is unfortunate, because the discoveries in East Africa promise an exponential increase in the wealth of those countries.

Map 1. Source: http://visualcapitalist.com, accessed February 4, 2021.

Oil Producers: Nigeria, Angola, Chad, and Equatorial Guinea

Nigeria, Angola, Chad, and Equatorial Guinea illustrate the impact of oil on African societies. When agencies of control do not exist, opportunities for corruption abound. However, it is likely that as oil exporting countries receive more wealth, the revenues enable state construction that includes more agencies of horizontal accountability. After agencies of horizontal accountability are established, policymakers are incentivized to use the revenues efficiently. In effect, oversight of the oil production value chain (exploration, extraction, depositing royalties, taxes, and fees in government accounts, refining, and marketing) earns more revenues for the exporting country. Movement along the oil value chain begins with exploration and progresses quickly to extraction and the depositing of bonuses, royalties, taxes, and fees. It is neither linear nor without mishap and resistance from officials.

As a chemical, oil’s comparative quality kindles different companies’ enthusiasm to invest in a country, thereby enhancing its relative international importance. Quality varies according to a crude oil’s density, sulfur content, and pour point (Smil Reference Smil2003:15). Petroleum’s density is either light or heavy, as measured in degrees of American Petroleum Institute (API) gravity. A heavier oil costs more to extract. Crude oil with a low hydrogen sulfide content is called sweet, and it is cheaper to refine. Once reserves have been located in subterranean reservoirs, the oil’s API gravity and composition must be determined. Profits are a function of the cost of extraction and refining. It is the oil’s quality that attracts companies, according to the market value of the crude they hope to extract. The market value of a sweet light crude is higher than that of a heavy sour oil.

Governments of oil exporting countries that depend on revenues for fiscal expenditures are vulnerable to price volatility and exogenous shocks. In periods of prices downturns and exogenous shocks, countries with high-quality oil continue production, but in those countries with heavy, sour crude, production slows. In early 2020, the global pandemic, an exogenous shock, seriously reduced the demand for oil, and petroleum companies cut production. Fiscal revenues crashed as the value of a barrel of oil dropped so low that some African governments needed to borrow money to pay basic public sector services. How the price crash, diminished revenues, and funding cuts disrupted each oil exporting country’s public sector services is an unfolding story. Disruptions have compelled policymakers to re-evaluate their countries’ dependence on resource revenues.

Petroleum production has increased dramatically since the 1957 discoveries in colonial Nigeria and Gabon. By 2020, almost thirty African countries were exporting oil. Petroleum represents a crucial source of revenues for all of these countries. Although hydrocarbon production contributes to an increase in gross domestic product, negative impacts include the “Dutch disease,” wherein factors of production move to the booming natural resource sector, leaving the economy vulnerable to price downturns (Corden & Neary Reference Corden and Neary1982). In each exporting country, the industry has contributed to the emergence of what Michael Watts (Reference Watts, Appel, Mason and Watts2015) and Jane Guyer (Reference Guyer, Appel, Mason and Watts2015) respectively call an “oil complex” or “oil assemblage.” Organizations and actors emerge and cluster around the sector, seeking rents and wealth. Positive entrepreneurial behavior among local populations occurs alongside wretched venality and sometimes violent criminality.

Nigeria is sub-Saharan Africa’s leading hydrocarbon producer. This extraordinarily dynamic country has a diversified economy that is the largest in Africa. Although Nigeria possesses 34 billion proven barrels of sweet, light crude, petroleum has had an uneven impact on the country’s over 200 million inhabitants. The oil reserves are mostly in the Niger Delta, a coastal plain of approximately 70,000 square kilometers that hosts 30 million people (Watts Reference Watts2004). In addition to crude oil, Nigeria has over 200 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of proven natural gas fields and a further 600 TCF in unproven fields. In short, Nigeria is a giant in all senses.

To manage its oil sector, Nigeria has a highly complex fiscal regime. The Nigerian National Petroleum Company receives a portion of the crude oil lifted by concessionaries. Companies make deposits into the unmonitored Domestic Crude Allocation accounts that are controlled by the NNPC (Sayne et al. Reference Sayne, Gilles and Katsouris2015:16). Frequent corruption scandals have involved stunning sums of money (Gillies Reference Gillies2020). Indictments of dishonest Nigerian officials have resulted in few incarcerations and account for Transparency International’s (TI) 2019 Corruption Perception Index ranking of Nigeria as 146 of 180 countries.

Angola is sub-Saharan Africa’s second leading oil exporter. Oil production began in 1967; however, it has been declining substantially since 2019. Today, Angola possesses reserves of 9.5 billion barrels almost entirely in deep-water blocks located in the Lower Congo Basin (IMF 2018:6). Its population of 30 million inhabitants includes an emerging middle class. Before the global pandemic, Angola had one of the world’s fastest growing economies. From 1979 until 2018, Jose Eduardo Dos Santos was General Secretary of the ruling Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola (Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola – MPLA) and president of Angola. Through management of the state-owned oil company, Sonangol, Dos Santos, his children, and associates in the army and MPLA amassed incredible fortunes (Soares De Oliveira Reference Soares De Oliveira2007a).

After João Lourenço won the MPLA election in 2017, he became the General Secretary and president. Dos Santos moved to Barcelona to a life in exile. Even though he had left, legacies of poor governance were evident in his clan’s grip on multiple productive sectors, often in collaboration with an oligarchy of military officers and regime cronies. Lourenço launched an anti-corruption campaign in September 2018 and set about dismantling the Dos Santos clan networks. Exposés of the Dos Santos clan and their allegedly ill-gotten billions attest to the grip of corrupt individuals (Freedberg et al. Reference Freedberg, Alecci, Fitzgibbon, Dalby and Reuter2020). Corruption is a serious issue in Angola. In 2019, TI ranked Angola 146 out of 180 countries.

Chad joined the African oil exporting community in 2001. From its reserves of 1.5 billion barrels of oil, Chad exports 130,000 barrels a day. Earnings from oil accounted for an increase in GDP from USD1.4 billion in 2000 to USD11.3 billion in 2019, with a concomitant increase in its per capita purchasing power parity (PPP) income from USD765 in 2000 to USD1,645 in 2019 (World Bank 2019). Meanwhile, primary school enrollment improved from 64 percent in 2000 to 88 percent in 2016 (World Bank 2019). Increases in income and school enrollment occurred in spite of the country’s income inequality. Chad’s fiscal regime includes concessions with cash-calls and equity participation (IMF 2019a:48). Unlike many African oil exporting countries, Chad is remarkable for its efforts at transparency and for the public availability of oil contracts (World Bank 2019:19). However, conflict, dictatorship, and venality have been common in Chad. Corruption is systemic, and this is reflected in the 2019 TI ranking of 162 out of 180.

Equatorial Guinea is among the newer African oil producers. With a population of 1.355 million and an average annual GNI per capita of USD6,460 (World Bank 2019), oil looms large in the economy, accounting for nearly 90 percent of the country’s exports. Despite the country’s substantial petroleum wealth, common Equatoguineans have received few benefits from the millions gained from offshore oil production (Appel Reference Appel, Appel, Mason and Watts2015). With the exception of its first election in 1968, which was democratic, brutally authoritarian regimes have ruled Equatorial Guinea. The country’s first president, Francisco Macias Nguema, imposed a breathtakingly ruthless regime. His nephew, Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, overthrew the government and ordered his uncle’s execution in 1979. Obiang Nguema established a dynastic dictatorship in which he distributed the key offices of state to his clansmen, who have siphoned off the wealth earned from its offshore reserves. In short, the country is remarkable for relatively high economic growth rates, extreme income inequalities, corruption, and repression. Equatorial Guinea is among the world’s most corrupt countries, such that in 2019 TI ranked it at 173 out of 180.

Resources & Revenues

Oil’s vulnerability to exogenous shocks became starkly apparent in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic preceded a significant drop in prices. Oil companies began to sell down their assets, as the pandemic exposed the vulnerability of African states. Even before the pandemic, public officials had to negotiate contracts that included local content requirements. These provisions stipulate that international companies engage domestic firms and thereby keep a greater percentage of resource revenues in-country (Ovadia Reference Ovadia2016a). Local content requirements are increasingly part of the fiscal regimes in African oil exporting countries. Although their impact on local communities should, normatively, be positive, compliance remains ambiguous.

Many countries, including Angola, Nigeria, and Ghana, require that contracts have local content policies to promote engagement with domestic companies (Ovadia Reference Ovadia2016a:20–21; Ovadia Reference Ovadia2016b; Hilson & Ovadia Reference Hilson and Ovadia2020). Policymakers intend, thereby, to transform oil production and its impact on local communities. Angola and Nigeria had long ago inserted local content requirements into their contracts. Ghana, which became an oil exporting country after the Jubilee Field came into production in 2010, established the Enterprise Development Centre (EDC) to embed local content and build domestic capacity in oil and gas production (Ablo Reference Ablo2020:322).

Local content requirements demonstrate the importance of community voice in Africa’s low- or low-middle-income oil exporting countries. People in communities know that their governments receive substantial sums of money from petroleum production and standardize “revenue collection, budget preparation, budget planning, expenditure execution, procurement, reporting and oversight” (Deléchat et al. Reference Deléchat, Fuli, Mulaj, Ramirez and Xu2015:5n7). These laws and rules compose the fiscal regime that set royalties, taxes, local content requirements, signature bonuses, and production sharing (Calder Reference Calder2014). Responsibilities for the government include setting up accounts into which oil companies deposit payments, opening ministries to interact with investors, and establishing national oil companies to participate in production sharing and joint ventures.

Any fiscal regime is a product of negotiations between oil companies and national officials. In the late 1970s, Gobind Nankani (Reference Nankani1979) drew attention to the asymmetries between highly trained oil executives who negotiated fiscal regimes and their far less-prepared African officials. Those disadvantages have ended. African states now employ local engineers and specialists trained at top European and North American universities. Many of these individuals began their careers with the supermajors—ExxonMobil, ChevronTexaco, Shell, BP, Total, or ConocoPhillips—and established domestic companies or worked for national oil companies such as Sonangol, the Nigerian National Petroleum Company, and the Ghanaian National Petroleum Company. They are every bit the equals of executives with the supermajors.

As an increasing number of African countries are now oil exporters, the effect of their adopting fiscal regimes is a process by which different countries construct new ministries, departments, and agencies to manage the industry. Of course, this process requires recruitment of competent personnel and enforcing fiscally responsible procedures. It seems probable that these new offices and employees may improve transparency in the petroleum sector and bring about greater accountability from public authorities.

Oil as a metaphor

Oil often functions as a metaphor for different policies and behaviors. For some, the substance signifies modernity, finance, geopolitics, or violence; it is the “ur-commodity, the mother of all commodities that enables all other commodities” (Appel, Mason, & Watts Reference Watts, Appel, Mason and Watts2015:10). Hydrocarbons are energy, whether to heat homes or to provide fuel for automobiles, trucks, aircrafts, and shipping. As energy, oil is part of a system wherein some people have access to its benefits while others do not. It is a measure of economic well-being. A recent concept has proposed that energy justice has eight elements, including availability, due process, good governance, sustainability, intergenerational equity, intragenerational equity, and responsibility (Sovacool & Dworkin Reference Sovacool and Dworkin2015:439). This normative theory “aims to provide all individuals, across all areas, with safe, affordable, and sustainable energy” (McCauley et al. Reference McCauley, Heffron, Stephan and Jenkins2013).

Petroleum production transfers to exporting countries the praxis of market capitalism (Schubert Reference Schubert2017:6). In Argentina, Elana Shever argues, oil is linked to neoliberalism, and its “profound state and economic restructuring” includes privatization of state companies, opening of markets to transnational corporations, and anti-labor policies (Shever Reference Shever2012:11). Shever’s triad recalls Michel Foucault’s observation that neoliberalism shows “how the overall exercise of political power can be modeled on the principles of a market economy” (Reference Foucault and Senellart2004:131). It follows that oil production compels exporting countries to accept capitalist reasoning with its emphases on free markets, rational accounting, unorganized labor, and profits. Foucault notes that these practices can be “broken down, subdivided, and reduced, not according to the grain of individuals, but according to the grain of enterprises” (Reference Foucault and Senellart2004:241). It is the capitalist oil enterprises that determine policies and practices among national elites.

James Ferguson (Reference Ferguson2010) asserts that fiscally strapped African politicians had no choice but to accept neoliberal prescriptions that pushed them into the capitalist world economy. These prescriptions included privatization, fiscal management, and reforms derived from the Washington Consensus (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2010; Williamson Reference Williamson1993; Harvey Reference Harvey2005; Watts Reference Watts2018). For David Harvey, neoliberalism is “dispossession” and a process of taking money from the poor and transferring it to the wealthy (Reference Harvey2005:159). Formerly impoverished oil-exporting countries were victims first of colonial rule, then of post-colonial dependency. Later, multilateral banks “crammed” neoliberal structural adjustment programs “down their throats” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2006:71). However, those who argue the neoliberal critique tend to portray African leaders and subjects in oil-exporting states as passive victims.

Neoliberalism is a term often used without definitional rigor beyond an unspecified conclusion that it refers to undesirable outcomes, including globalism, imperialism, privatization, and capitalism (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2010:166). Rooted in this critique is a belief that oil production in Africa occurs in “our contemporary world of downsized states and unconstrained global corporations” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2005:378). The process of oil extraction in Africa contributes to the continent’s continued “exclusion and marginalization” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2006:194). Neoliberal policies are “bad for the poor and working people” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2010:166). African leaders and their citizens are therefore victims of international organizations that “coerce” them to accept structural adjustment programs and “scientific capitalism” (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2006:78).

Of course, even a cursory examination of the empirical record denies that if policymakers can just get it right (e.g. implement the reforms outlined in the Washington Consensus), then all good things will follow. Case after case suggests that this is not necessarily so. Indeed, Africa’s extraordinary growth rates, especially in countries that resisted all the prescriptions embedded in structural adjustment programs, contradict the structural critiques of neoliberal theory. African oil exporting countries have emerged from extreme poverty according to their own fashion. Even as the impact of the global pandemic is slowing economic growth, African oil exporters continue to receive resource revenues. Their policymakers may very well use these revenues to finance new state organizations that promise more effective government.

The Curse/Blessing Dichotomy

Dichotomous reasoning has contributed to polemical studies that one-sidedly fail to explain how petroleum influences African life. The “resource curse” theory for one is a deterministic perspective for which the scenario is simple: oil companies discover reserves, production begins, economic growth follows, exchange rate distortions consistent with the Dutch disease harm the economy, poverty increases, and political leaders impose authoritarian regimes (Auty Reference Auty1994; Ross Reference Ross2012). Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner (Reference Sachs and Warner1995) correlate abundant natural resources with an enormous number of variables to show “empirically” negative impacts. Terry Lynn Karl (Reference Karl1997) and Michael Ross (Reference Ross2001) developed resource (oil) curse arguments stating that in economies with abundant hydrocarbon resources, growth is elusive. For their acolytes, politicians consolidate corrupt dictatorships (Gillies Reference Gillies2020; Jensen & Wantchekon Reference Jensen and Wantchekon2004; Tsui Reference Tsui2011). Nicholas Shaxson (Reference Shaxson2007:7) asserts that it is not “oil companies but oil itself—the corrupting poisonous substance.” Women and the poor often suffer disproportionately (Ross Reference Ross2012). It is a dreadful picture.

However, overly deterministic arguments resting on saturated statistical models have obscured causal inference and raised doubts about the theory. Arguments for the resource curse were that political leaders of countries with abundant natural resources always adopt inefficient policies or impose autocracy. Skeptics questioned this dogma, asserting that natural resources were really a blessing. As Thad Dunning commented, “Resource rents can promote authoritarianism or democracy, but they do so by different mechanisms” (Reference Dunning2008:4). Economists Michael Alexeev and Robert Conrad (Reference Alexeev and Conrad2009) showed that oil production is actually a net benefit to low-income countries. Stephen Haber and Victor Menaldo (Reference Haber and Menaldo2011) argued that critical data suggest that petroleum enhances democracy. Kelsey O’Connor and associates (Reference O’Connor, Blanco and Nugent2018) used time series data to question the tenuous link between oil and authoritarianism. These analysts argue that correlations between abundant natural resources and authoritarianism cannot show causality. Hence, after years of the resource curse canon, a growing number of observers argue that petroleum is wealth that can and does pay for education, health care, infrastructural development, and the establishment of democratic institutions (Ayuk & Marques Reference Ayuk and Marques2017; Haber & Menaldo Reference Haber and Menaldo2011; Heilbrunn Reference Heilbrunn2014; Menaldo Reference Menaldo2016; O’Connor et al. Reference O’Connor, Blanco and Nugent2018).

The resource blessing framework offers an alternative perspective. It is counterintuitive to think that when oil companies began to deposit funds in government accounts, undesirable developmental outcomes necessarily follow. In a previous publication, I argued that it is necessary to understand the diverse conditions in each oil exporting country before production started to assess the subsequent impact of oil revenues on development (Heilbrunn Reference Heilbrunn2014). The case of Chad is instructive. After the initial deposit of signature bonuses, President Idriss Déby Itno, who was formerly a warlord, seized the money to buy military hardware, contrary to agreements with the Consortium of oil companies and donors (Heilbrunn Reference Heilbrunn2014:4; Stern Reference Stern2000). Déby justified the seizure as his right to defend his regime against insurgencies and invest in education and health care. Indeed, the World Bank reports that in 2016, 87 percent of Chad’s primary school age children attended classes; oil provided the revenues that were a mixed blessing for Chad’s children, who were growing up under a harsh dictatorship.

However, nothing is simple, and the binary polemic obscures as much as it illuminates. Oil exporting countries build state agencies. In many countries, these agencies demonstrate the continuity of political settlements rather than discontinuity. Countries continue on the paths on which they were traveling before oil production. For example, in 1992, Ghanaians voted to approve a referendum to establish a republican democracy. Successive presidential elections resulted in parties alternating in power without coups or any contestation of results. Democratic elections predated oil discoveries, and Ghana has continued to enjoy democratic government since that time. The receipt of petroleum revenues did not move the Accra government or its military to intervene and impose authoritarian rule, as advocates of resource curse arguments might have predicted.

By understanding the conditions in effect when oil production begins, it is possible to comprehend how policymakers choose to manage resource revenues. This simple proposition is that countries under dictatorships remain authoritarian after the discovery of oil. For instance, in 2017, Heritage Oil and Gas reimbursed the Ugandan state for back taxes; President Yoweri Museveni used these revenues to extend “the presidential handshake” to reward clients and clansmen (Brophy & Wandera Reference Brophy, Wandera, Langer, Ukiwo and Mbabazi2020:78; Hickey & Izama Reference Hickey and Izama2017:173). Although stories abound of leaders who use resource revenues to consolidate power, the inverse is also evident in Angola and Nigeria.

Environmental disaster

When spilled, oil is toxic. When burned off in illegal gas flaring, it pollutes the air. Oil exporters face numerous predicaments resulting from negligent extraction. Sometimes, the guilty party is absent. In 2015, oil soiled the coast of Angola’s Cabinda Province. As reported in the Angolan offical press, no one took responsibility, which left the local population to clean up the spill (Agencia Angola Press 2015). In other circumstances, the oil company sometimes refuses to take responsibility. In 2013, spills in Chad implicated the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC). The CNPC refused to acknowledge involvement in the spill or pay to clean it up, so Chadian authorities suspended CNPC’s contract (Nako Reference Nako2014). Some companies try to minimize the cost of the disasters, despite evidence to the contrary. Suzana Sawyer tells how companies in Ecuador and Nigeria report a single measure of hydrocarbon pollutants to obscure and minimize the differences among toxic substances (Reference Sawyer, Appel, Mason and Watts2015:145). Perhaps the most egregious example has been the spills in the Niger Delta.

The Niger Delta serves as a poignant reminder of oil extraction’s risks. Indeed, the United Nations Environmental Program issued a shocking report, stating that it will take decades to repair the damage in Ogoniland (UNEP 2011:12). Spills have despoiled fish stocks and ruined agricultural lands. This environmental degradation radicalized the local people who lost their livelihoods due to recurring oil spills (Adunbi Reference Adunbi2015). Royal Dutch Shell, speaking for SPDC-Nigeria, stated that for most spills, its lawyers’ interpretation of existing laws indicated the Nigerian government was responsible for cleanup (WAC Global Services 2003). In these instances, they simply walked away. However, given how long these spills have been occurring and the extent of environmental damage, it is difficult to avoid a conclusion of willful corporate negligence (Hennchen Reference Hennchen2015:9). This perspective is precisely what one judge in the Netherlands concluded in January 2021, when the court ordered Royal Dutch Shell to pay unspecified damages for spills that caused widespread environmental damage in Oruma and Goi, two villages in the Niger Delta (Raval & Munshi Reference Raval and Munshi2021).

In the Niger Delta, multiple non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and their leaders have struggled against corporate arrogance (Adunbi Reference Adunbi2015:18). In vain, the NGOs have demanded compensation for the injustices imposed on the Niger Delta’s residents. A consequential fury, Rebecca Timsar (Reference Timsar, Appel, Mason and Watts2015:88–89) suggests, shaped the creation, absorption, and channeling of rebellion by youth groups, which is evident in resurgent Egbesu worship “firmly rooted in Ijaw historical cosmology.” These NGOs denounce the SPDC executives, government officials, and local community leaders whose collusion has resulted in relentless poverty, unemployment, and despair.

Unemployment among the Niger Delta’s youth is a serious consequence. To overcome their poverty, unemployed youths tap pipelines and sell crude oil on regional and international markets (Watts Reference Watts2004:50; Peel Reference Peel2010). Youths participate in “a dizzying and bewildering array of militant groups, militia, and so-called cults” (Watts Reference Watts2008:8). According to Omolade Adunbi (Reference Adunbi2015:45), local populations believe that oil companies have irresponsibly polluted their land before absconding with their inheritance. Residents suffer unemployment and misery while living alongside wells that expatriate abundant wealth and give little succor to the Niger Delta people. Herein is the story that Adunbi, Watts, and others have told.

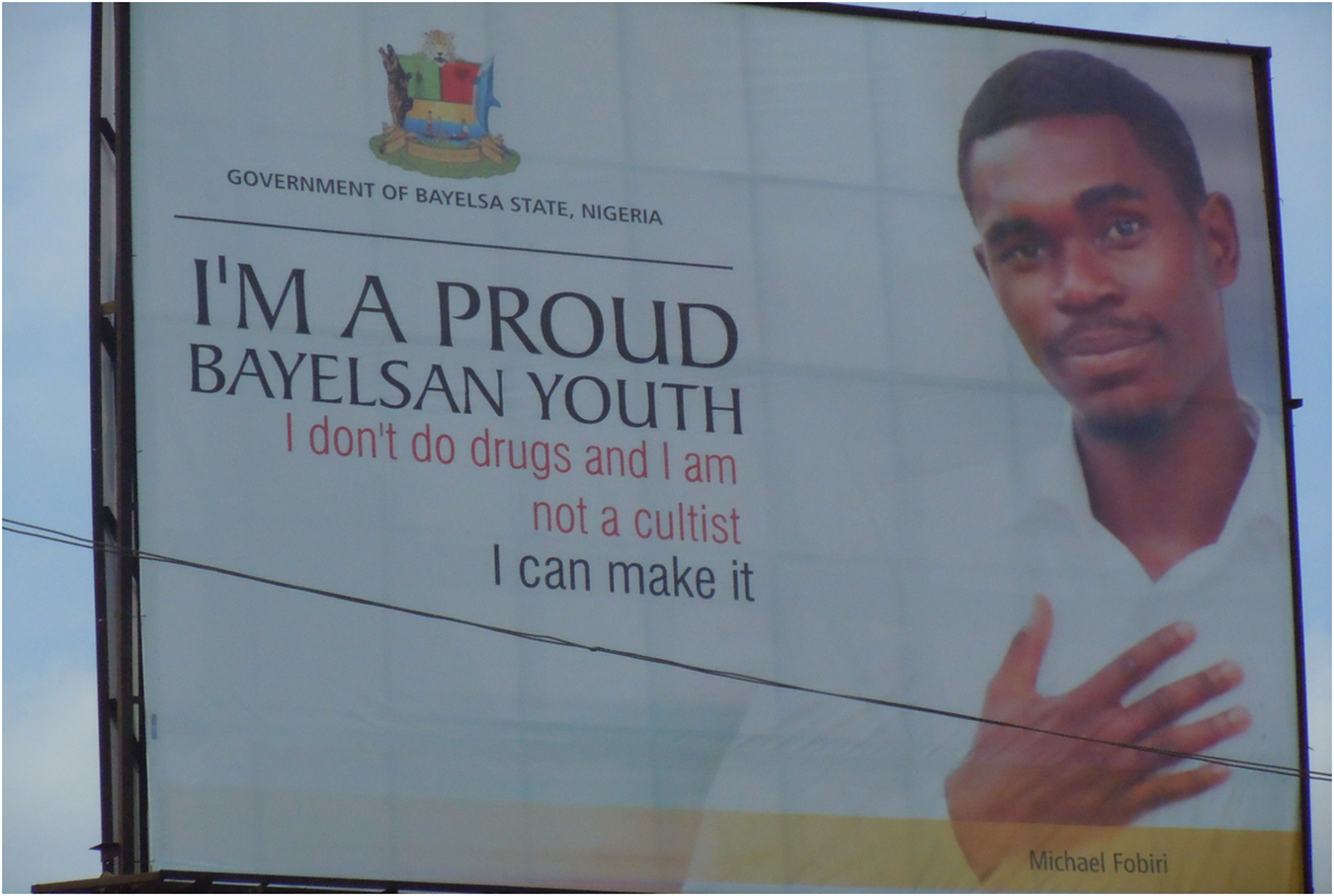

In May 2013, the billboard below (Figure 1) greeted travelers entering Yenagoa, Bayelsa State. The wholesome young man pledges to avoid drugs and cult groups. His is an optimistic image of Delta youth. Whereas the billboard displays hope, the residents’ continued destitution has contributed to violence, desperation, and drug abuse. Adunbi (Reference Adunbi2015) emphasizes the local belief that oil companies excluded the Niger Delta’s youth from employment, education, and opportunities while extracting incredible riches for shareholders of international corporations headquartered in Europe and North America.

Figure 1. Government of Bayelsa State Billboard at entry to Yenagoa, Capitol of Bayelsa State, Nigeria. John Heilbrunn photo from personal files, 2013.

The organization of petroleum theft is a major activity that implicates high-ranking military and navy officials, politicians, and national and international oil executives (Watts Reference Watts2004, Reference Watts2008:8). Estimated losses of around 20 percent of Nigeria’s production due to oil theft seem staggering. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala states that in 2012, oil bunkering diverted an average of 150,000 barrels a day from Niger Delta wells and accounted for losses of approximately USD1 billion a month (Okonjo-Iweala Reference Okonjo-Iweala2018:41). The tapping of pipelines causes explosions and oil spills for which, in case after case, Shell Nigeria blamed local populations for causing the environmental disasters (WAC Global Services 2003; Shell Nigeria 2014).

However, the extraordinary quantities of crude that are stolen could only occur with the connivance of local government councils, state governments, and officials in the Federal Government (Davis Reference Davis2007:5; Gelber Reference Gelber, Appel, Mason and Watts2015; Katsouris & Sayne Reference Katsouris and Sayne2013). The trade involves young men who tap pipelines, offload barrels onto barges and onshore tankers, or refine gasoline in artisanal refineries to distribute regionally (Gelber Reference Gelber, Appel, Mason and Watts2015:276, 280; Oruwari Reference Oruwari2006:3; Watts Reference Watts2006a:22; Watts Reference Watts2008:15). The petroleum disappears through “deeply entwined” webs of people in oil companies, the state, and local communities (Gelber Reference Gelber, Appel, Mason and Watts2015:274–75, 285). Once the oil enters international waters, brokers sell it and transfer payments to shadow networks in Nigeria and abroad (Ellis Reference Ellis2016:86).

Because the various networks that profit from oil production exclude the Delta’s Ijaw, Itsekiri, and Ogoni communities, these populations militantly oppose the FGN and oil companies that, as Adunbi (Reference Adunbi2015) emphasizes, took their birthright and gave nothing in return. Militants thus justify protection rackets, toll collection (passage), and fees as “late” payments (Adunbi Reference Adunbi2015:197). They resent the northern military leaders who governed Nigeria for most of its independent history and treated oil revenues as their personal wealth (Siollun Reference Siollun2019:197–98). People complain that Abuja, the Federal capital, thrived only because of stolen oil wealth (Adunbi Reference Adunbi2015:163). Meanwhile, the state refuses to protect its citizens from careless and arbitrary corporate negligence (Adunbi Reference Adunbi2015:162; Watts Reference Watts2006b; Watts Reference Watts, Appel, Mason and Watts2015; Gelber Reference Gelber, Appel, Mason and Watts2015).

In an attempt to mediate the costly conflict in the Niger Delta, President Musa Yar’Adua proclaimed an amnesty program in 2009. However, local communities’ demands for jobs, help in cleaning up oil spills, and a greater share of oil wealth went unanswered (Adunbi Reference Adunbi2015:219). The amnesty program did nothing to alleviate the alienation of the youth from “political, civil, social, customary, and religious authority” (Watts Reference Watts2018:479). Young men continued to join gangs and to serve as foot soldiers for extraordinarily powerful “godfathers” who had influence over decision-making in Abuja and each petroleum exporting state (Hellerman Reference Hellermann2010; Sklar, Onwudiwe, & Kew Reference Sklar, Onwudiwe and Kew2006). The influence of the godfathers in Nigeria, which is hard to overstate, is indicative of the perverse incentives in the post-authoritarian country. In this regard, petroleum is one element yet hardly the main cause of alienation in Nigerian society.

Communities

Oil communities include individuals on whom oil production has a direct and discernable impact. Southwestern Chad, where the Consortium of oil companies has been lifting oil, has a tropical climate and largely agrarian population. Chad is a landlocked former French colony that has received scant scholarly attention. The story of oil production in Chad began in 1977, when Conoco obtained an exploration license from the government (Nolutshungu Reference Nolutshungu1996:94). Elf Aquitaine (today Total) objected to the entry of an American company (Nolutshungu Reference Nolutshungu1996; Petry & Bambé Reference Petry and Bambé2005). Conoco subsequently located reserves with a crude between 18.8˚ and 25˚ API gravity (Bacon & Tordo Reference Bacon and Tordo2004:23; Nolutshungu Reference Nolutshungu1996). However, complex production logistics and political instability interfered with oil production.

In 1991, President Déby approached Esso, Shell, Elf, the Caisse Française du Développement, and the World Bank to figure out how to start production. Negotiations resulted in the World Bank guaranteeing loans to develop the Doba fields and construct the Chad-Cameroon Pipeline Project.Footnote 2 It was an enormous success for Déby, who viewed oil as a means to break free from postcolonial relations (Nolutshungu Reference Nolutshungu1996:298). He agreed to establish a number of offices, open offshore accounts to receive payments, and use revenues for development purposes. Despite the misgivings of some World Bank staff members, the agreement went through, and the Consortium began drilling for oil.

The agreement, however, was doomed. First, the World Bank team that negotiated the agreements had an inadequate understanding of internal Chadian politics (Gary & Reisch Reference Gary and Reisch2005:42–48). The team failed to recognize that for Déby, oil revenues were windfalls (Behrends & Hoinathy Reference Behrends and Hoinathy2017:58). Although the World Bank demanded that oil revenues be used to finance development projects, Chadian communities received little in the way of training or local content transfers. Events in Chad affirmed Raymond Vernon’s concept of an obsolescing bargain (Vernon Reference Vernon1971; Gould & Winters Reference Gould and Winters2007). Once Déby began to receive revenues in 2002, he immediately purchased arms and declared he had a right to use the funds as he saw fit. It quickly became clear that World Bank officials had “grossly overestimated” their ability to influence the former warlord; they had behaved as though he was weak, disengaged, and amenable to their tutelage (Pegg Reference Pegg2009:312). However, Déby was neither weak nor disengaged; rather, he was duplicitous and unambiguously corrupt. Hence, when his nephews Timane and Tom Erdimi organized a rebel force that in 2016 invaded N’Djaména, Déby denounced his agreement with the World Bank and stopped deposits into the offshore accounts.

An influx of capital had a direct impact on the Chadians who lived in communities near the installations and interacted directly with the Consortium. Dignitaries in local communities negotiated directly with the Consortium in spite of their relatively weak positions (Leonard Reference Leonard2016). Within a short time, internal social cleavages emerged in agrarian communities near the Oil Field Development Area (OFDA) in Bero, Komé, and Miandoum (Leonard Reference Leonard2016:23). First, literate people sold letter-writing services to help citizens who wished to make claims regarding ownership, damages, and grievances, or to mediate disputes (Leonard Reference Leonard2016:44, 48; Barclay & Koppert Reference Barclay and Koppert.2007). Second, when land increased in value, the Consortium set a non-negotiable scale (barème) for what it would pay for damages (Leonard Reference Leonard2016:70–74). The commodification of land and literacy in southern Chad introduced relations consistent with a “nearly neoliberal state” (Leonard Reference Leonard2016:67–68). Production transformed the local community and empowered entrepreneurial actors in southern Chad.

Finally, construction of the Chad-Cameroon Pipeline Project began while there was ongoing instability in the northern Borkou/Ennedi/Tibesti (BET) region. This mountainous desert region had been the historic point of departure for numerous guerilla movements. The Erdimi twins began their revolt from the BET region, where they received local support. Déby seized oil revenues to buy arms, reward his clients, and weaken traditional authorities (Debos Reference Debos2016:143). Internal rivalries among members of Déby’s clan reflected competition among factions in his Bideyat Zaghawa ethnicity. Chad was neither at war nor in peace (Debos Reference Debos2013:48). Although the country was exporting oil and receiving resource rents, communities in southwestern Chad continued as before the beginning of production.

Corruption

Corruption, the abuse of position for private gain, is widespread and systemic in many African oil exporting countries. Whether discussing Nigeria’s “missing billions” (Katsouris & Sayne Reference Katsouris and Sayne2013; Wallis Reference Wallis2013; Premium Times), the dos Santos clan’s fortune (Forsythe et al. Reference Forsythe, Gurney, Alecci and Hallman2020), Claudia Sassou-Nguesso’s USD7 million New York City apartment (Global Witness 2019), the almost USD2 billion that Mozambican authorities embezzled from natural gas-backed loans (Friends of the Earth International 2020), or Teodorin Obiang Nguema’s houses in California, South Africa, and Paris (Le Monde 2019), the response to Carlos Leite and Jens Weidman’s Reference Leite and Weidmann1999 question ‘Does Mother Nature Corrupt?’ is a resounding yes! Many alleged cases of malfeasance are evident.

Leakage of resource revenues is unfortunately common in oil exporting countries. In Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, Angola, and Chad, corruption is far more than a symptom of misrule. It is a breakdown of constraints on public officials and employees of private oil companies. On one hand, officials believe they have impunity. Presidents in many oil exporting African countries control the accounts into which oil companies deposit taxes, fees, and bonuses; they see these accounts as slush funds for their personal use (Collier et al. Reference Collier, Ploeg, Spence and Venables2010). On the other hand, employees of oil companies want to increase the profits for shareholders, even if that means they must break laws. They are sometimes willing to bend rules to secure contracts for lucrative reserves. In part, quick money in Nigeria, Angola, Equatorial Guinea, and Chad encourages people who want to make profits. However, to focus only on corrupt incidents obscures the extraordinary growth and opening of political expression occurring in many oil exporting countries. In this regard, oil has been a blessing.

Corruption is a term commonly used in analyses of many oil exporting countries. The many and varied reasons for systemic corruption suggest that oil companies do not care about a host regime’s due diligence (Ayuk & Marques Reference Ayuk and Marques2017:25), and controls over dishonesty are absent. In Tanzania, discoveries of 57.25 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of recoverable natural gas preceded allegations that authorities had embezzled resource revenues (Choumert-Nkolo Reference Choumert-Nkolo2018; Poncian & Jose Reference Poncian and Jose2019). In Mozambique, Anadarko and ENI announced the discovery of enormous natural gas fields. Shortly thereafter, government officials allegedly solicited loans over USD1.4 billion, or 78 percent of the country’s GDP (IMF 2019b:5; Tvedten & Picardo Reference Tvedten and Ricardo2018:6; Friends of the Earth 2020; Kroll Associates Reference Associates2017; Orre & Rønning Reference Orre and Rønning2017:12). In both cases, few controls prevented officials from illicit enrichment. Scandals became examples of too much money too quickly available in a state with too few controls.

Nigeria has lived with “pervasive, massive, and unabashed malfeasance throughout the public and private sectors” (Lewis Reference Lewis2007:140). In the twentieth century, a succession of military dictators countenanced the theft of stunning sums from the oil sector. The country became a showcase of how oil facilitates corruption (Gillies Reference Gillies2020; Arezki & Gylfason Reference Arezki and Gylfason2013; Sala-i-Martin & Subramanian Reference Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian2013). In 2013, the governor of the Nigerian Central Bank submitted a politically explosive letter to President Goodluck Jonathan in which he alleged that the NNPC had stolen USD50 billion in crude oil earnings (Sanusi Reference Sanusi2013). European authorities launched investigations of Diezani Alison-Madueke, whom they eventually detained in London while British and Nigerian officials scrutinized her accounts to recover stolen assets (Munshi Reference Munshi2020).

A second case started in 1998 when the Italian supermajor, ENI, and Shell allegedly transferred an estimated USD1.1 billion to Malabu, a firm owned by General Sani Abacha’s Petroleum Minister Dan Etete (Olawoyin Reference Olawoyin2020a). The oil companies wanted to acquire exploration/production rights to OPL 245 and its 560 million barrels of oil. It took years for judicial authorities to unravel the case and recover some of the stolen assets. The trial in Milan concluded with prosecutors demanding a ten-year prison sentence for Etete, eight years for former ENI executives Claudio Descalzi and Paolo Scaroni, and seven years four months for Malcolm Brinded, Shell’s former head of upstream operations (Olawoyin Reference Olawoyin2020a). Although the Nigerian government had tried to recover the money distributed to former President Goodluck Jonathan, former Attorney General Mohammed Adoke, and former Petroleum Minister Alison-Madueke, Etete was practically untouchable (Olawoyin Reference Olawoyin2020b).

In Equatorial Guinea, the alleged corruption of Obiang Nguema’s clan has resulted in wide-ranging investigations in France, the United States, and South Africa (Rice Reference Rice2012). Hannah Appel (Reference Appel, Mason, Watts, Appel, Mason and Watts2015:253; Reference Appel2020:27–28) observes how at different stages in the value chain, corrupt proceeds may be used to sustain a repressive and corrupt regime. Compared to Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea is a small producer, with reserves of around 1.1 billion barrels from which, in 2016, oil companies extracted 280,000 barrels a day (World Bank 2019). Although its 1.2 million people live in what was once one of the world’s fastest growing economies, it was also one of the most inequitable. The Obiang clan dominates the state to such a degree that close family members own the companies that furnish security, transportation, and the apartments for oil company personnel. Indeed, the president’s son, Teodorin Obiang Nguema, was infamous for his collection of rare automobiles, his real estate in California and on the Indian Ocean coast between Cape Town and Durban, and apartment buildings in Paris, all on a modest minister’s salary (Gurrey Reference Gurrey2012).

Ricardo Soares De Oliveira begins his elegant study of Angola’s postwar reconstruction with the slogan “Angola starts,” but by the book’s conclusion, he despairs that a deeply corrupt and entrenched oligarchy has left most Angolans impoverished to “suffer and die of preventable diseases and have a life expectancy that barely reaches 50” (Reference Soares De Oliveira2015:211–12). The history of this shocking inequality begins at Angola’s independence in 1975, when its political elite engaged in an intractable civil war (Cramer Reference Cramer2006; Messiant Reference Messiant2006; Soares De Oliveira Reference Soares De Oliveira2015). Between 1975 and 2002, two principal combatants, the MPLA under Jose Eduardo Dos Santos and Jonas Savimbi’s National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola —UNITA) fought for control of the country’s enormous natural resource wealth. While the MPLA diverted oil revenues to finance its war effort, UNITA seized rents from the diamond mines. Neither Dos Santos nor Savimbi had a compelling interest in ending the war (Soares De Oliveira Reference Soares De Oliveira2007b). In effect, petroleum and diamonds financed a conflict that dragged on for decades, wasted a king’s fortune, and cost countless lives.

After the war ended in 2002, the Dos Santos government launched an ambitious reconstruction program. The president’s clan and associates reaped fortunes through corrupt networks and contracts (Soares De Oliveira Reference Soares De Oliveira2015; Pearce et al. Reference Pearce, Péclard and Oliveira2018). In 2017, João Lourenço, the newly elected general secretary of the MPLA and president, put an end to dos Santos clan’s illicit behavior. To start, Lourenço dismissed Isabel dos Santos as head of Sonangol, launched investigations into how she and her late husband Sindika Dokolo had amassed billions, and seized her accounts (Freedberg et al. Reference Freedberg, Alecci, Fitzgibbon, Dalby and Reuter2020; Forsythe et al. Reference Forsythe, Gurney, Alecci and Hallman2020). The Lourenço administration opened investigations into Isabel dos Santos’s brother José Filomeno dos Santos and his management of the sovereign wealth fund, the Fundo Soberano de Angola (FSDEA), from which he allegedly embezzled USD500 million (Pilling Reference Pilling2019; Pearce et al. Reference Pearce, Péclard and Oliveira2018). Authorities jailed the younger Dos Santos; his release within seven months suggests the clan enjoys continued immunity from prosecution and punishment (Jornal de Angola Reference Angola2019). However, their unrestrained consumption of oil wealth had ended.

When oil prices increased from USD10.00 a barrel in 1999 to USD147.00 a barrel in 2008, the MPLA regime received a bonanza. It protected the “unregulated global capitalism of the neoliberal era and the activist capitalism of resource-rich states” (Soares De Oliveira Reference Soares De Oliveira2015:169). Oil-backed loans from China helped Dos Santos centralize executive power and blur any lines between private and public sector oil revenue management (Soares De Oliveira Reference Soares De Oliveira2015:173). Those days are over. A slowdown that began in 2016 preceded the collapse of oil prices due to the 2020 global pandemic. Hence, the culture of corruption that permeated Angola and its elites has ceded its position to austerity programs, calls for good governance, and economic retrenchment.

Oil as Keyword?

Whether framed as a blessing or a curse, oil is a productive keyword for African studies. Even in those circumstances where individuals use their positions to seize government wealth, it seems implausible that they can grab it all. More plausibly, oil revenues provide policymakers with the funds necessary to hire people who work in ministries, agencies, and departments. The resulting mix of policies, laws, and regulations constitute a country’s fiscal regime, all elements of a more efficacious state. The influx of money gives a country’s leaders the means to reduce inefficiencies. Of course, nothing is absolute or linear; however, contrary to the pessimistic determinism of resource curse arguments, this essay proposes that by enabling state construction, oil wealth contributes ultimately to better governance and less corruption.

Hydrocarbon production accelerates an exporting country’s integration into the world economy. Nigeria, for one example, has assumed a critical role in West Africa and the global economy, to which a constant parade of news stories in international newspapers such as The Financial Times attests to its importance. Of course, not all the stories are salutary; many are reports about astonishingly brazen corruption scandals. During the twenty-first century, African oil exporting countries experienced significant increases in GDP that accompanied their integration into the world economy. With the announcement that Nigerian public health officials detected the first case of COVID-19 on February 29, 2020, the pandemic had a decelerating impact on oil exporting economies. However, it seems likely that African oil exporting countries will continue to be crucial players in the global economy.

Oil as metaphor continues to animate research about petroleum and its impact on common people in oil exporting countries. Many analysts use “oil” to signify modernity, neoliberalism, globalism, local content, and so on. They contend that through neoliberal policies, political leaders thrust their countries into the global capitalist economy. Politicians have had no choice but to accept structural adjustment programs with unduly punitive conditions. Embedded in this critique is a notion that petroleum production introduces a network of donor organizations and “experts” who promulgate policies that often harm common African people. One undisputable critique of neoliberalism is that the analyses avoid counterfactual reasoning. Instead of asking what an oil exporting country might have experienced in the absence of reforms, they assert that oil is a curse. It therefore takes the position that petroleum necessarily condemns a country’s people to lower incomes and life under the yoke of autocratic rule.

Oil wealth has diverse impacts under different political conditions. For example, local content requirements have a positive impact on African populations in oil exporting countries. Local firms in Angola, to some extent, have taken advantage of these laws to participate in reconstruction projects. In Chad, when the Consortium started field development, property values increased and residents paid literate neighbors who, for a fee, drafted letters for them, seeking compensation. In the Niger Delta, oil as wealth was no less a factor in the emergence of armed militia that targeted oil rigs. Threats of violence often convinced oil companies to declare a force majeur, stop production, and withdraw their personnel. Possible explanations for these events that aggravate an already tense situation include pervasive unemployment among a youthful population and the failure of oil companies to invest in regional development.

Corruption, often skulking in the background, occurs at different points in the oil value chain. In some countries, the dishonesty is systemic. Corruption in Nigeria has been evident in a succession of scandals involving astounding sums of money. Yet, the country’s economy has continued to grow, and it is now the largest in Africa. However, whether discussing Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea, Angola, or Chad, impunity among high level officials enables corrupt transactions. People are not deterred from stealing money that is a direct outcome of oil production. Indeed, with the debatable exception of Ghana, practically all African oil exporting countries have experienced systemic corruption to greater or lesser effect. Hence, although oil is a chemical that can do nothing on its own, it correlates with unfortunate outcomes in low- and low-middle income African countries.

Since 1975, more and more African countries have explored for, discovered, and begun exporting oil. This growing number of producers attests to why oil is a keyword in African studies. It is a keyword that informs debates about the impact of natural resources on development and social well-being. For sure, oil is wealth. As wealth, oil enables countries to experience positive effects that include increased investments in education and health care. However, even in the best cases, growing wealth brings out the worst in human behavior. Corruption has been part of numerous scandals in oil exporting countries. Corporate greed is evident when companies seeking increased shareholder profit have negligently failed to maintain productive facilities. Only the most callous of observers can minimize the environmental catastrophes in places like the Niger Delta.

As a keyword in African studies, oil becomes synonymous with a variety of conditions that arise in exporting countries. Entry into the ranks of oil exporting countries triggers novel relations with international actors and organizations. Money from the petroleum industry influences political and social relations. An understanding of oil’s centrality to economic growth and political development is a critical element of this keyword that is so important for so many exporting countries. This kind of analysis owes a debt to anthropology, economics, political science, and sociology. Viewing oil as a keyword in African studies seem an ideal method for linking different disciplines and bridging disciplinary silos.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the excellent reviewers’ comments I received and Benjamin Lawrance’s outstanding editorial acumen. Of course, all remaining errors are mine alone.