Before 2000, the law in Scotland relating to people with a mental disorder was archaic and fragmented. The Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984 did not fundamentally alter the spirit of the previous 1960 Act. Mental health law had therefore fallen well behind modern thinking and clinical practice. Even worse, some of the law relating to incapacity dated from the 16th century. An overhaul of law relating to mental health and incapacity was overdue. The Scottish Parliament has now passed two important pieces of legislation, the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 (which I call here the 2000 Act) and the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 (the 2003 Act). Although this article concentrates on the provisions of the 2003 Act, it is important to briefly examine the 2000 Act as the tone of the latter guided much of what was to follow.

The 2000 Act

The 2000 Act was the result of a major review of incapacity law in Scotland. Publication of a review and recommendations by the Scottish Law Commission (1995) had led to a statement by the Scottish Executive (1999) outlining its plans to introduce legislation in the Scottish Parliament and to the presentation of the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Bill. The subsequent Act was one of the first significant pieces of legislation passed by the Scottish Parliament. The 2000 Act, the main features of which are listed in Box 1, was implemented in stages between April 2001 and October 2003.

Box 1 The Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000

The main features of the Act include:

-

• a set of principles that must be applied to any intervention under the Act

-

• a definition of incapacity

-

• new provisions for appointment of individuals with power of attorney

-

• simple mechanisms to operate bank accounts of people with incapacity

-

• changes to the law on management of funds in hospitals and care homes; this replaced and repealed similar mechanisms under the 1984 Act

-

• new legislation on medical treatment

-

• flexible orders for single interventions and for welfare and financial guardianship

Interface with the 2003 Act

Both Acts allow for treatment and welfare interventions where a person has a mental disorder that interferes with capacity. However, some features of the 2000 Act limit the extent of interventions and may necessitate the use of the 2003 Act. For example:

-

• the section on medical treatment, unless immediately necessary, does not authorise force or detention

-

• a welfare guardian cannot place an individual in hospital for treatment for mental disorder against that person's wishes

-

• if a person does not comply with decisions made by their guardian, a sheriff may make a compliance order, but again this could not extend to mental health hospital treatment.

The 2003 Act

The 2003 Act was the product of a wide consultation carried out under the auspices of a committee chaired by the Right Honourable Bruce Millan. The Millan Committee had a wide variety of stakeholders and heard evidence from many interested parties. It reported in 2001 (Scottish Executive, 2001) and a Bill was introduced in early 2002. The Act was passed in 2003 and implemented in October 2005.

As with the 2000 Act, the 2003 Act is built on a set of principles. These vary slightly from the ‘Millan Principles’ produced by the Millan Committee and the wording is not as strong as that of the principles stated in the 2000 Act. Before considering the innovations in the 2003 Act, it is worth mentioning that certain features of the previous Act (the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984) were abolished, and with good reason. These include the following.

-

• Hearings in the sheriff court This is the local court in Scotland and it deals with criminal and civil cases. There is no direct equivalent in other parts of the UK. The Millan Committee recognised that this was not an appropriate forum for decisions on compulsory mental health treatment. Sheriffs still play a role in relation to some appeals.

-

• Consent and application for admission by relatives The Millan Committee was concerned about the effect that these powers might have on subsequent relationships within the family. There is no such power in the 2003 Act.

-

• Emergency orders as the only route of admission Under the 1984 Act, the only route for compulsory admission in Scotland had been an emergency order unless application was made to the sheriff. Emergency orders for 72 h had become the route of admission in the vast majority of cases. Just over half of these progressed to a further short-term order lasting up to 28 days. It had not been possible to invoke a short-term order without first detaining the person on an emergency order.

Main provisions of the 2003 Act

Duties of various bodies

The 2003 Act describes the duties of the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland and expands its role to include monitoring the operation of the Act and promoting best practice in its use, including observance of its principles. In addition, the Commission has various safeguarding functions, including duties to inquire, visit, advise and publish its findings.

The 2003 Act established the Mental Health Tribunal for Scotland (www.mhtscot.org). The tribunal makes decisions on applications, reviews, appeals for revocation and applications for variations relating to many of the orders under the Act. Each tribunal consists of a legal member, a medical member and a general member.

The Act defines the duties of health boards and local authorities, and introduces a new duty for local authorities to provide services designed to promote well-being and social development. Local authorities must provide specially trained social workers to act as mental health officers (MHOs). Health boards must compile a list of ‘approved medical practitioners’ (AMPs) with special experience in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorder. Regulations specify that AMPs must be Members or Fellows of the Royal College of Psychiatrists or have 4 years' whole-time experience in mental health. In addition, they must have completed an appropriate training course provided by the College. This has significant implications for psychiatrists who move from other countries, including other parts of the UK – they cannot become AMPs until they have been trained. A new duty for health boards is the provision of appropriate services for the care of younger people with mental health problems, whether detained or not.

Principles

Any person discharging functions under the 2003 Act shall have regard to:

-

• the past and present wishes and feelings of the patient

-

• the views of relevant others (named person, carer, guardian or welfare attorney)

-

• the participation of the patient

-

• information and support for the patient

-

• the range of options available

-

• the provision of maximum benefit

-

• non-discrimination

-

• respect for diversity

-

• minimum restriction of freedom

-

• the needs of carers

-

• information for carers

-

• the provision of appropriate services.

The Act also attaches great importance to the welfare of children (defined as a person under 18 years of age) and to observance of equal opportunity requirements.

Tests for compulsory care and treatment

The Act allows for compulsory care and treatment, which may or may not include detention in hospital. I use the term ‘subject to compulsion’ for a person treated under the Act.

Broadly, there are five criteria that need to be met before a person can be subject to compulsory treatment (Box 2). However, not all of these criteria apply to all orders under the Act (Box 3). In particular, under emergency and short-term detention certificates it is sufficient that the criteria are thought likely to be met. A registered medical practitioner must test that the criteria are met (or seem likely to be met).

Box 2 Criteria governing tests for compulsory care and treatment under the 2003 Act

-

• The person must have a mental disorder

-

• Medical treatment must be available

-

• The person's ability to make decisions about medical treatment must be significantly impaired because of mental disorder

-

• Without detention or treatment, there would be a significant risk to the person's health, safety or welfare, or the safety of another

-

• The making of an order must be necessary

Box 3 Orders authorised under the 2003 Act

Civil procedures

Detention

-

• Emergency detention certificate: only urgent treatment authorised

-

• Short-term detention certificate (28 days): required medical treatment authorised

Treatment

-

• Compulsory treatment order

-

• Interim compulsory treatment order

Criminal procedures

Pre-trial orders

-

• Assessment order

-

• Treatment order

Post-conviction and pre-sentence orders

-

• Interim compulsion order

-

• Remand for inquiry

Disposal on conviction and acquittal

-

• Compulsion order

-

• Compulsion order with restriction order

-

• Urgent detention of acquitted persons

-

• Transfer of prisoners (under a transfer for treatment direction or a hospital direction)

The presence of a mental disorder

The definition of mental disorder is a broad one and can be mental illness, intellectual (learning) disability or personality disorder. The following cannot be cited as the sole reason for the presence of a mental disorder: sexual orientation or deviancy; transsexualism; transvestism; alcohol or drug use or dependence; behaviour causing alarm, harassment or distress; and ‘acting as no prudent person would act’.

The availability of medical treatment

The Act defines medical treatment broadly and includes nursing care, psychological therapies, habilitation and rehabilitation. For emergency and short-term orders, the requirement is to detain the person to determine what medical treatment should be given. Under emergency orders, only urgent treatment can be given. Short-term detention certificates authorise all aspects of treatment under the Act.

Impaired decision-making ability regarding medical treatment

The Act does not define impaired ability to make decisions. The code of practice draws medical practitioners' attention to a suggested test but it is for the practitioner to justify an opinion that the criterion is met and for the mental health tribunal to listen to arguments to the contrary and reach a decision. This criterion does not apply to individuals subject to criminal procedures.

Risk to self or others

‘Welfare’ is a new addition to the risk test. Under the 1984 Act, admission had to be necessary in the interests of the patient's health or safety, or for the protection of others.

An order is necessary

This criterion reflects the Millan Committee's principle recommending ‘informal care where possible’. Emergency detention certificates are permitted only if making arrangements for the granting of a short-term detention certificate would involve undesirable delay.

Civil procedures

Emergency detention

Detention under an emergency order requires an examination and a certificate issued by any registered medical practitioner. Consent by an MHO is not an absolute requirement. If an MHO was not consulted, the medical practitioner must explain the reasons for this. The medical practitioner must also explain the reasons for granting the certificate and why alternatives to detention were considered inappropriate. Unlike the 1984 Act, there is an expectation that emergency orders will be used sparingly and either revoked at any early stage or superseded by a short-term order. For this purpose, hospital managers are required to secure an examination by an AMP as soon as possible after admission. Only urgent treatment is authorised during a period of emergency detention.

Short-term detention

Detention under a short-term order requires an examination by an AMP and must have the consent of an MHO. The latter should interview the patient but could make a decision on the best available evidence if interview is impossible. The MHO usually discusses the patient with the medical practitioner and together they decide whether the grounds for an order are met. A short-term order authorises detention in hospital for up to 28 days and administration of medical treatment. The responsible medical officer (RMO) may revoke the order at any time and may suspend the authority to detain. The patient or named person may appeal against the order to the mental health tribunal. In exceptional circumstances, the order may be extended to allow an application to the tribunal for a compulsory treatment order.

Compulsory treatment

A tribunal can authorise a compulsory treatment order only following an application from an MHO, who must also submit a report. In addition, there must be two medical reports, at least one of which must be by an AMP. The other may be by another AMP or by the patient's general practitioner. The measures authorised under a compulsory treatment order are listed in Box 4.

Box 4 Measures authorised under a compulsory treatment order

-

• Detention in hospital

-

• The giving of medical treatment, subject to part 16 of the 2003 Act

-

• Requirement that the patient attend for treatment, care or services

-

• Requirement that the patient reside at a specified place

-

• Requirement that the patient allow visits from certain persons

-

• Requirement that the patient inform and/or seek the approval of an MHO if a change of address is proposed

-

• ‘Recorded matters’, i.e. specific treatments or services that the tribunal considers appropriate. This reflects the Millan principle of reciprocity – the duty to provide care and services to a person subjected to compulsion

The order does not require detention in hospital in order for a person to have compulsory treatment. However, the 2003 Act is clear that treatment cannot be administered by force in the person's own home. A number of steps can be taken if the person does not comply with community treatment. First, if a person fails to attend for treatment, the Act allows for them to be taken to hospital or to the place specified in the treatment order for 6 h so that treatment may be given.

Second, the Act contains provisions for admission to hospital if the person does not comply generally with community-based compulsory treatment. This is for an initial 72 h period. If necessary, the person can be further detained for up to 28 days in order to decide whether application to the tribunal for a variation of the compulsory treatment order is needed to authorise continued detention.

A compulsory treatment order can last for 6 months, can be renewed for a further 6 months and then can be renewed annually. The RMO may review and revoke the order or may apply to the mental health tribunal for a variation in it. The patient or named person may also apply to the tribunal for a variation or revocation. The Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland may revoke an order or may make a referral to a tribunal. The tribunal, in addition to hearing appeals and referrals, scrutinises all orders at least every 2 years. The Act also permits interim orders to be made, usually in order to continue treatment pending a fuller examination of the case.

Mentally disordered offenders

The 2003 Act amends sections of the Criminal Procedures (Scotland) Act 1995 and overhauls the way mentally disordered offenders are managed.

Pre-trial orders

These carry restricted status and a Scottish Minister must approve any leave granted. There are two types of pre-trial order: assessment orders and treatment orders.

Assessment orders

These allow assessment in hospital for 28 days. The court may make an order on the evidence of one medical practitioner. Treatment can be given only if authorised by an AMP who is not the RMO.

Treatment orders

These can last for the duration of the pre-trial period and allow treatment in hospital. They require evidence from two medical practitioners.

Post-conviction and pre-sentence orders

Interim compulsion orders

These orders authorise detention in hospital (with restricted status) and medical treatment. They can last for up to 12 weeks and can be extended by the court. The total accumulated time cannot exceed 12 months. They require evidence from two medical practitioners.

Remand for inquiry

The court may order a convicted person to be remanded to hospital for inquiry into his or her physical or mental condition. There is no treatment power attached to this order.

Disposal on conviction and acquittal

Compulsion orders

Compulsion orders are very similar to civil compulsory treatment orders. They are made on the basis of two medical opinions and can authorise the same measures as compulsory treatment orders.

Compulsion orders with restriction orders

If an offence is particularly serious the court may impose both a compulsion order and a restriction order. A Scottish Minister must approve any period of suspension and will determine the level of security needed. The Mental Health Tribunal for Scotland still has the responsibility to conduct hearings, but the legal member/convenor must be a sheriff. The Act has recently been amended, following pressure from the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland and the Royal College of Psychiatrists, to allow a tribunal to revoke the restriction part of the order if satisfied that it is no longer necessary. Ministers may attach conditions to suspension of detention and to conditional discharge.

Urgent detention of acquitted persons

This is a new provision that allows a court to detain a person acquitted of an offence for medical examination for up to 6 h. Previously, some people were ‘double detained’ using civil procedures if there was a prospect of acquittal. Although not clearly unlawful, this is undesirable and the new provisions are an improvement.

Transfer of prisoners

A person convicted of an offence may be treated in hospital under a hospital direction or a transfer for treatment direction. These orders carry restricted status.

Medical treatment

The 2003 Act is much more prescriptive on the subject of treatment than were its predecessors. Any treatment needs either the patient's consent in writing or a written record of why treatment is in the patient's best interests if the patient does not consent or is incapable of consenting. This written record is also necessary if the person consents other than in writing. Urgent treatment must be notified to the Mental Welfare Commission. Safeguards exist for neurosurgery for mental disorder, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and medication continuing beyond 2 months. Regulations have added other treatments, including deep brain stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation and transcranial electromagnetic stimulation, to the list of safeguarded treatments. The Act also refers to designated medical practitioners (DPMs), who will give independent opinions for safeguarded treatments and ensure that an appropriate specialist gives an opinion on any child subjected to a safeguarded treatment.

Neurosurgery for mental disorder

Neurosurgery for mental disorder needs written consent, certification by a DMP and certification from two persons appointed by the Commission. There is provision for the Court of Session (Scotland's supreme civil court) to authorise such surgery for a patient who is incapable of consenting but is not objecting. It is not lawful to perform neurosurgery for mental disorder if the patient objects, whether capable or not. These provisions apply to both detained and informal patients.

Electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy can be given if the patient consents in writing and the RMO or a DMP certifies in writing that the patient has the capacity to consent. If the patient is incapable of consenting, a DMP must certify that treatment is in the patient's best interests. An incapable patient who resists or objects to ECT can be given this treatment only to save life, prevent serious deterioration or alleviate serious suffering. There are provisions for urgent treatment. A person who is capable of consenting but refuses cannot be treated with ECT, even in an emergency.

Prolonged medication

Medication beyond 2 months carries safeguards similar to those for ECT. The difference is that a ‘capable refusal’ can be overridden if a DMP has regard to that reason and explains why treatment should still be given.

Artificial nutrition and treatment to reduce sex drive

These treatments need either written consent or an independent opinion from a DMP from the outset.

Other urgent treatment

Urgent treatment not otherwise authorised in the Act must be recorded and reported to the Mental Welfare Commission.

Other new features of the 2003 Act

The 2003 Act has many other innovative and welcome sections that enhance the autonomy and rights of the patient and provide better regulation and safeguards where compulsory powers are used. The most important of these are outlined below.

Named persons

Any individual with a mental disorder may, when capable, appoint a named person. Should the individual, regardless of current capacity, be detained or treated under the 2003 Act the named person will receive information and has the right to be consulted about the use of certain orders. He or she can also apply to the tribunal for orders to be revoked or varied.

Advocacy

The Act gives any person with a mental disorder, whether subject to compulsion or not, the right to independent advocacy and places duties on health boards and local authorities to ensure that there is access to advocacy services. Although there is no duty to provide an advocate in individual cases, it is best practice for staff to help a person to engage with advocacy services.

Advance statements

The Act allows anyone, when capable, to make an advance statement regarding how he or she would and would not like to be treated in the future. Mental health tribunals, and anyone providing care and treatment, must have regard to that statement and must inform the patient, named person, attorney, guardian and the Mental Welfare Commission if care and treatment conflict with the statement and the reasons why.

Conditions of excessive security

There are mechanisms for appeal to the tribunal against detention in conditions of excessive security. At the time of writing, this is only available to people in the high secure State Hospital in Lanarkshire.

Communications, safety and security

Regulations authorise restrictions on communications and on visitors, and searches of patients. Except for people in the State Hospital and in Scotland's medium secure units, there must be documented reasons for imposing any such restrictions. The Mental Welfare Commission has an important role in monitoring the use of these powers.

Informal patients

A mental health tribunal may, on application, decide that an informal patient is being unlawfully detained in hospital.

The impact of the new legislation

At the time of writing, the 2003 Act has been in operation for about 2 years. The following findings are therefore early ones and need to be interpreted with caution. However, they are interesting and they reveal some important unintended consequences of the Act.

Overall use of powers

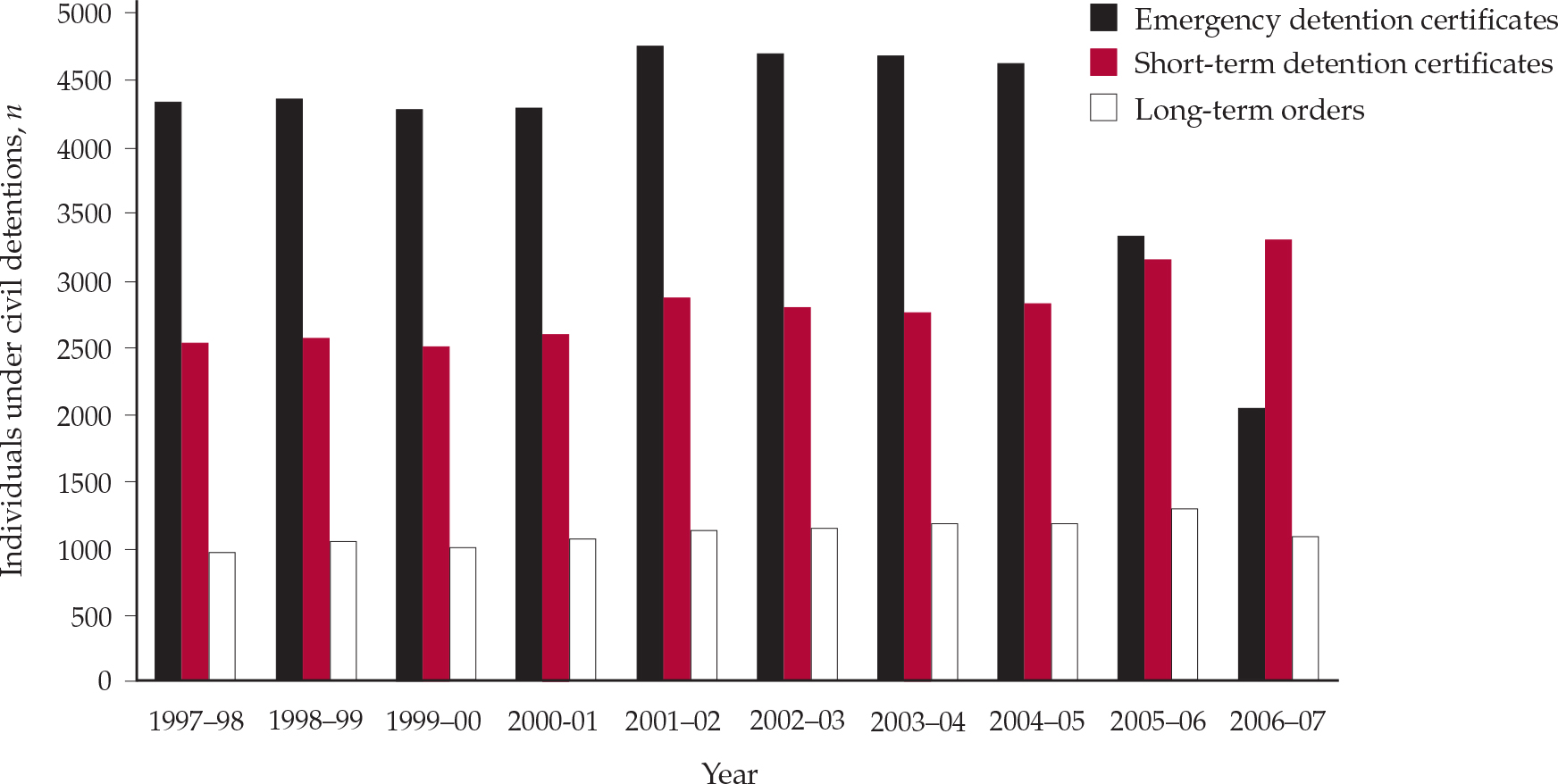

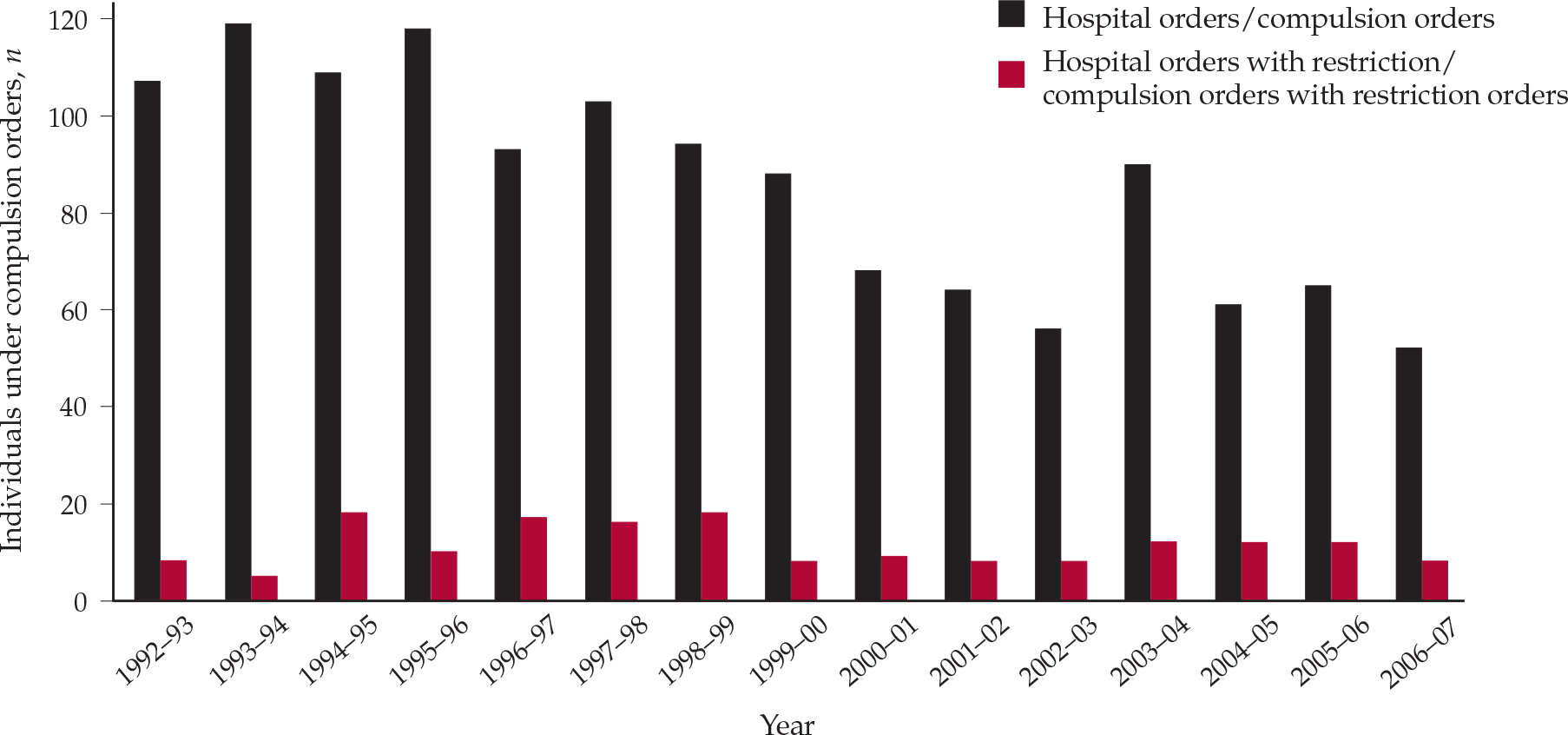

Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the use of the main civil and criminal powers of Scottish legislation. The 2005–6 figures are hard to interpret because the 2003 Act was implemented half way through that year. However, in 2006–7 the Act significantly reduced the number of emergency detention certificates by around 60% (Fig. 1). As short-term detention for 28 days became the usual route into compulsory treatment under the 2003 Act (as opposed to the 72 h emergency order under the superseded 1984 Act), it was possible that people would be detained for longer. Figures from the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland (2006, 2007) suggest that around 8–9% more people are now detained for more than 72 h. These data also show that, outside working hours, most people are still detained under emergency certificates. However, the total number of people subject to compulsion has fallen. In 2006–7, there were 4379 new episodes of detention. Previously, there were between 4700 and 4800 new episodes each year (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, 2007). There is no increase in the use of long-term orders.

Fig. 1 Number of people subject to detention orders under civil procedures in Scotland from 1997–98 to 2006–7 (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, 2007; by permission).

Fig. 2 Number of people subject to compulsion orders under criminal procedures in Scotland from 1992–3 to 2006–7; hospital orders were the equivalent of compulsion orders under previous legislation (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, 2007; by permission).

Overall, there has been a reduction of 8% in the total number of people subject to compulsion under the 2003 Act (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, 2007). The reasons for this are unclear. Practitioners might be uncertain about the new legislation. It could be that the criterion of ‘impaired ability to make decisions about treatment’ has reduced the number of people thus detained.

Use of the 2003 Act for specific groups

Data published by the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland (2006, 2007) break down impositions of the 2003 Act by patient group.

Ethnic minorities

Data are incomplete but around 4% of people subject to compulsion are from a minority ethnic group. There is no evidence of over-representation of any particular ethnic group.

Younger people

There is evidence that more children and young people are subject to compulsion. Eleven people under the age of 16 were treated under the 2003 Act in 2006–7. This is a significant increase on previous years and may reflect increasing statutory interventions for people with eating disorders. Further monitoring and research is under way.

Older people

The use of short- and long-term compulsion for the over-65s doubled between 2005 and 2007. People with dementia comprise the vast majority of this group. This may reflect a change in practice following the ‘Bournewood judgment’ ( HL v. UK [2004]), practitioners being more likely to apply for formal detention orders for hospitalised people with dementia if there is significant deprivation of liberty.

Community-based compulsory treatment

During 2006–7, over 300 new community-based compulsory treatment orders and variations to existing orders to authorise community treatment were granted. The number of people subject to community-based compulsory treatment orders at any one time rose from 131 to 268 (Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, 2007).

Interim orders

Around half of all applications for compulsory treatment orders result in at least one interim hearing (e.g. www.mwcscot.org.uk/Rights&TheLaw/Statistics/Statistics.asp). As the 2003 Act requires a mental health tribunal to hear and test the evidence for an interim order, the unintended consequence has been up to three hearings to determine one order. This can be time-consuming and distressing. The Scottish Government has recognised this and is undertaking a limited review of the Act at the time of writing.

Services for younger people

The Act requires the provision of age-appropriate services and accommodation for all people under the age of 18 who receive mental healthcare in hospital. In Delivering for Mental Health (Scottish Executive, 2006), the Scottish Government made a commitment to reduce the number of admissions of young people to non-specialist facilities by 50% by 2009. In 2007, 187 such admissions were reported to the Mental Welfare Commission. Of these, 20% had no specialist input to their care while on adult wards. Urgent action is needed if the Government is going to meet its commitment.

Principles and safeguards

Table 1 summarises information gathered by the Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland from its visits to people subject to compulsion.

Table 1 Findings from visits to people subject to compulsion, 2006–7

| Provision | Finding |

|---|---|

| Advocacy | Almost all patients service users aware but only 30% uptake |

| Advance statements | 60% of patients knew about them but only 2–3% had made one1 |

| Named persons | 75% of patients were aware of provisions and had either nominated or been content with a default named person |

| Information | Good evidence that all patients, carers, etc. had been given information, but about 25% lacked understanding. Hospital managers are required to give and explain information |

| Participation | 70% of patients had involvement in their care plans but many did not have a copy or know where to find one |

| Carers | Good evidence of involvement in about 75% of cases |

Burden on practitioners

It was evident from the outset that the 2003 Act would require more of psychiatrists' time (Reference Atkinson, Brown and DyerAtkinson et al, 2002). However, early data show that the requirements of the new Act have more than doubled the time that psychiatrists spend on procedures related to compulsory treatment (Reference Atkinson, Lorgelly and ReillyAtkinson et al, 2007). The MHOs face a similar problem. Early surveys of psychiatrists show mixed views about mental health tribunals and a consistent view that the amount of time spent on Mental Health Act work has significantly increased (Reference Carswell, Donaldson and BrownCarswell et al, 2007). The cost of this is high, not merely in monetary terms but also by potentially reducing the time available for informal patients – the vast majority of most psychiatrists' work. Changes to the design and content of forms were introduced in August 2007 and there is a limited review of the Act under way at the time of writing. However, both studies mentioned here (Reference Atkinson, Lorgelly and ReillyAtkinson et al, 2007; Reference Carswell, Donaldson and BrownCarswell et al, 2007) show that psychiatrists are committed to the new Act and its principles and believe that adherence to its principles will result in better care and a better experience for the patient.

Conclusions

New mental health legislation in Scotland is complex and significantly changes the way that people are given compulsory care and treatment. Early data on the operation of the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 suggests that practice has changed, but that some problems with the operation of the Act need to be addressed before everyone can be comfortable that it is achieving its goal of principle-based intervention that puts humane and ethical care and treatment first.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

-

1 The principles of the 2003 Act do not include:

-

a ensuring maximum benefit for the patient

-

b using the least restrictive option in relation to the patient's freedom

-

c giving appropriate information to carers

-

d providing advocacy

-

e providing services in return for compulsion.

-

-

2 In relation to civil compulsory powers:

-

a named persons can consent to detention

-

b the tribunal hears only appeals against detention

-

c community-based compulsory treatment must follow a period of detention in hospital

-

d more people are subject to compulsion than under the previous 1984 Act

-

e short-term detention should be the usual route into compulsion.

-

-

3 In relation to safeguards under the 2003 Act:

-

a only a person nominated by the patient can be the named person

-

b advance statements are legally binding

-

c a mental health tribunal can rule that a patient is being kept in conditions of excessive security

-

d detention automatically authorises searching the patient

-

e only detained persons have a right of access to advocacy.

-

-

4 Mentally disordered offenders:

-

a can be given treatment under an assessment order without an additional opinion

-

b must have impaired decision-making ability to be given mental health treatment

-

c can be subject to restrictions only after conviction

-

d are restricted when transferred from prison

-

e can never be released from restrictions even if they are no longer necessary.

-

-

5 In relation to treatment under the 2003 Act:

-

a ECT can be given to people who make a capable refusal

-

b artificial feeding is not subject to special safeguards

-

c medication can be given for up to 3 months to non-consenting patients before an independent opinion is needed

-

d rehabilitation is included in the definition of medical treatment

-

e emergency detention does not authorise treatment, even if it is urgently needed.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F |

| b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F | b | F |

| c | F | c | F | c | T | c | F | c | F |

| d | T | d | F | d | F | d | T | d | T |

| e | F | e | T | e | F | e | F | e | F |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.