In the late fall of 2017, the University of Iowa (UI) Office of the State Archaeologist (OSA) was contacted by John Palmquist of Stanton, Iowa, about formally donating his family's archaeological collection to the State Archaeological Repository (Davis and Doershuk Reference Davis and Doershuk2019). This collection was recovered with landowner permission primarily from agricultural fields and stream-cut banks in Montgomery and Page Counties in southwestern Iowa during 40 years of surface survey by John and his son, the late Phil Palmquist. John Palmquist, in addition to being a longtime Iowa Archeological Society (IAS) member, has participated in several projects led or mentored by professional archaeologists—including field schools, site monitoring, and archaeological surveys and excavations—and he is widely known by the Iowa professional archaeological community as a passionate and involved avocational archaeologist. Using current Society for American Archaeology (SAA)–approved terminology, John Palmquist readily meets the definition of a “responsible and responsive steward” (RRS; Society for American Archaeology [SAA] 2018) because he has always secured permission before surveying fields, never disturbed known sites, and clearly documented and recorded the geographic location of his finds through submission of relevant details to the official state site record—the Iowa Site File (ISF). Concerned about the long-term fate of his collection, Mr. Palmquist sought assistance from OSA to facilitate bequeathing it to the State Repository for continuing preservation and use for future research and engagement. We saw this as an opportunity to explore a collaboration that could promote public understanding and support for the long-term preservation of the archaeological record.

CHALLENGES OF ARCHAEOLOGIST–COLLECTOR COLLABORATION

As has been well documented (Shott Reference Shott2017:126), avocational collectors of archaeological material “are vastly more numerous than are professionals . . . [and the] fact of large-scale private collection is no secret” among professionals. The implications for the conduct of systematic unbiased archaeological research are profound (Schiffer Reference Schiffer1996), but as Shott (Reference Shott2017) notes, until relatively recently, the profession has largely ignored these worries. Many researchers avoid engaging with collectors, often raising justifiable concerns regarding accuracy of provenience data. We sympathize with this view given that in recent years, the OSA has rejected the donation to the State Archaeological Repository of several large (in terms of numbers of artifacts) collector-generated assemblages because there were no associated records that would permit assignment of items to specific (or even generalized) site locations with research value. In one instance, the OSA was contacted by a family that had inherited more than 10,000 artifacts from reportedly “dozens of locations”—which their father (and grandfather), who were avid collectors for decades, bequeathed to them—but all that was known about provenience was that “most of the materials were probably from Iowa.” These situations are made worse when there is evidence of some materials in a collection having been bought and sold, which not only introduces the potential for fake items to be in the collection but also increases the potential geographic range from which legitimate items may have originated. These vagaries of provenience and legal acquisition render such collections of little research value, and there is scant justification for them occupying scarce curation space.

However, professionals connecting with collectors provides invaluable opportunities for improving archaeological knowledge of underrepresented areas. This is arguably becoming increasingly important in the age of social media and easy internet-based transactions in order to stem the rising tide of private collections becoming less accessible to professionals as aging collectors (or surviving family members) sell or otherwise disperse artifacts to individuals unconnected or unconcerned with the contextual details surrounding actual discovery of items—if such data were, in fact, ever recorded. We encourage colleagues to work toward greater integration of collector knowledge and of collections as a routine aspect of research practices. Professionals should, in our opinion, seek to develop a larger cadre of RRSs than currently exists and actively assist with establishing permanent curation arrangements for well-documented privately generated collections. In this article, we share details of our experience with successful professional–collector interactions concerning the long-term disposition of a private collection. We briefly introduce the project partners in the collaborative effort, provide examples of similar OSA–RRS collaborative efforts, describe a grant received to support the transfer of the Palmquist Collection to the State Repository and associated curation steps, and explore details of the collection and one avenue of research we are currently pursuing using artifacts from the collection. We conclude with a discussion of the benefits we see resulting from meaningful collaboration between RRSs and professional archaeologists.

PROJECT PARTNERS

The Palmquist family and OSA staff were central to the collaboration that resulted in the Palmquist Collection being transferred to the State Archaeological Repository, but other key organizations that assisted include the IAS and the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs (DCA) as well as the Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates (ICRU). DCA provided essential grant funds, matched in part by ICRU, that specifically allowed a team of three undergraduates to participate.

As noted, the OSA houses the State Archaeological Repository (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Cordell, Pitzen, Ash, Lensink and Pauls2004), and it is an organized research unit of the University of Iowa. Established in 1959, the OSA currently reports to the vice president for research. It is affiliated through several adjunct faculty appointments with the UI Department of Anthropology. The mission of the unit is to develop, disseminate, and preserve knowledge of Iowa's human past through Midwestern and Plains archaeological research, scientific discovery, public stewardship, service, and education. The OSA conducts archaeological research and public programs around the state, preserves ancient burial sites, and examines and reinters ancient human remains. The OSA also manages data on all recorded archaeological sites in Iowa and publishes technical and popular books and reports on Iowa archaeology. Several OSA archaeologists teach courses through the UI Department of Anthropology. Each academic year, several University of Iowa students undertake independent study projects and thesis research at the OSA, hold work-study jobs supported by the unit, and are hired as field and laboratory technicians during summers or after graduation. UI students and students from other colleges also participate in OSA research through semester-long and summer internships, or as volunteers. Of importance to the discussion of collaboration with RRSs, adult volunteers can participate in OSA-directed archaeological field experiences, where they obtain training in archaeological methods while contributing to important research. They can also volunteer their time at the OSA, where they assist with projects involving archival maps, photographs, and documents and collections of all types of archaeological artifacts.

A primary OSA mission is to serve as the State Archaeological Repository for the State of Iowa (Cordell et al. Reference Cordell, Doershuk, Lensink, Childs and Warner2019). OSA, like other archaeological repositories, seeks to preserve nonrenewable information from archaeological sites, even after these places are physically destroyed by accidental natural processes or intentional human development. Archaeological repositories are the backbone of accrued scientific knowledge about the past, and they are crucial in supporting effective comparative research by future generations of archaeologists. The OSA has maintained a repository since 1959 with some curated materials collected more than a century ago. The OSA facility is currently the largest and best-organized archaeological repository in Iowa, as evidenced by the State Historical Society of Iowa choosing to house its unparalleled Charles R. Keyes Collection (~400 sites and 100,000 artifacts) of archaeological materials there (Tiffany Reference Tiffany1987). In total, the OSA curates approximately 4,000,000 artifacts representing 11,000 Iowa archaeological sites, with additional collections being added each year—primarily from cultural resources management (CRM) archaeological compliance projects but also through acceptance of select privately generated collections donated with appropriate locational details (Cordell et al. Reference Cordell, Doershuk and Lensink2018).

Established in 1951, the IAS is a nonprofit organization that welcomes archaeological professionals, avocational archaeologists, students, and other members of the public who share an interest in Iowa's archaeological past. The goals of the IAS include fostering cooperation between professional and amateur archaeologists, promoting the study and interpretation of archaeological remains in Iowa, disseminating knowledge and research in archaeology and related disciplines, recording and preserving sites and artifacts, and developing constructive attitudes toward these objectives through public education and outreach—in effect, developing RRSs. A principle of membership in the IAS is that members shall not engage in the buying, selling, or trading of artifacts. Members of the Association of Iowa Archaeologists, a nonprofit organization of professional archaeologists conducting research in the state of Iowa, are required by their bylaws to also be IAS members, with the explicit goal of providing guidance to the avocational community. OSA staff members work with the IAS mentoring the Site Surveyor Certification program that provides training for IAS members to increase the quality and accuracy of site reporting. John Palmquist completed his IAS Site Surveyor certification in 1977 (Palmquist Reference Palmquist1977), setting him and his family on a constructive path of becoming an RRS and contributing useful scientific data on archaeological sites in their region of the state.

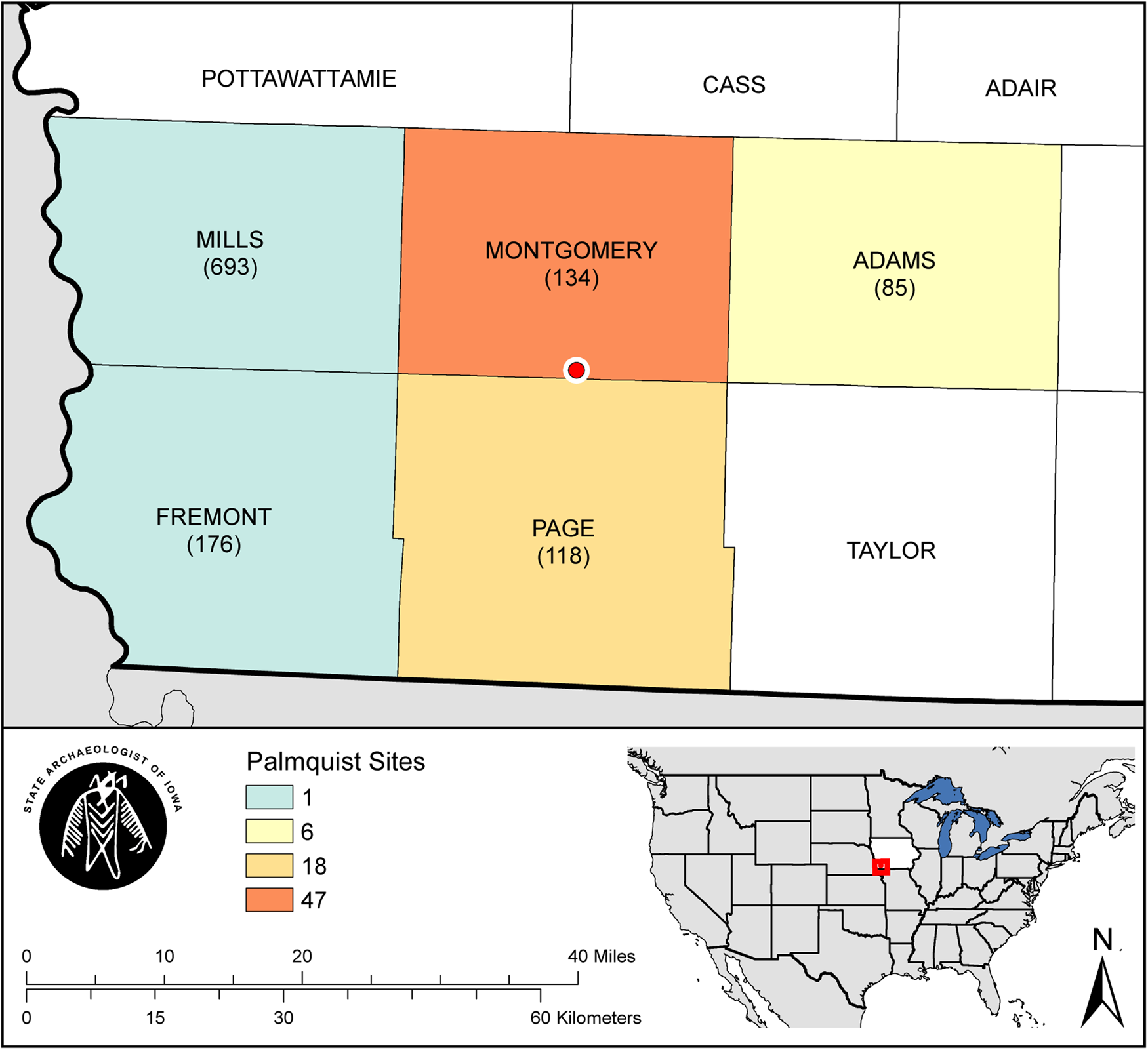

The ISF, the official state database of recorded archaeological sites, has significantly fewer sites recorded in the southwest quadrant of the state, where the Palmquists reside, than elsewhere. This relative absence of recorded sites reflects, in part, the lack of population centers in these counties and consequent infrastructure development and associated Section 106 CRM archaeological investigations. The statewide county average is currently just over 300, albeit with wide variability by county. Although Mills County (ca. 700 recorded sites)—the location of an unusual concentration of Glenwood-phase Central Plains tradition earth lodges and peripheral to the Omaha metropolitan area—has been the subject of numerous archaeological investigations over the years, as of 2018, only 513 sites had been recorded in total for the other four southwestern-most Iowa counties. Of these, 73 of the sites were recorded by John and Phil Palmquist (Figure 1). Many other ISF sites in southwestern Iowa are likewise recorded thanks to the efforts of dutiful and responsible avocational archaeologists.

FIGURE 1. Map of southwestern Iowa counties showing the approximate location of the Palmquist home (red dot) with county recorded site totals as of 2018. Palmquist site counts are color coded by county.

As mentioned earlier, John Palmquist is a longtime member of the IAS and was an early adopter of IAS and OSA best practices for responsible avocational collectors of archaeological materials. He created a tracking system in which he routinely recorded information concerning when and where he found specific artifacts. He maintained a box and bag system that isolated materials from individual sites from artifacts found at other locations, thereby preserving provenience data. John recognizes the importance of context in archaeology and has worked toward recording artifacts and their associations in his collection. He is also an honorary member of the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska (Harvey Reference Harvey2005) and is well aware of cultural sensitivities about archaeological practices and ethical collecting (Renander Reference Renander2009), a concern promoted by the OSA and reflected in the SAA's RRS criteria (Figure 2). As John has aged, he has recognized that his ability to maintain his curatorial system is increasingly at risk. His acceptance of this fact helped him make the decision to donate.

FIGURE 2. Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska induction ceremony photo. John Palmquist's appreciation for archaeological context also extends in his artifact collecting habits to great respect for the Indigenous cultures whose ancestors produced these items. John received a rare honor among archaeological collectors—that of being inducted into a modern tribe. This reinforces the value of the Palmquist Collection becoming part of the State Archaeological Repository. (Photo from Harvey Reference Harvey2005, used with permission of the Iowa Archeological Society.)

RRS AND RESEARCHER COLLABORATION

As we have suggested, despite potential pitfalls and shortcomings, there is excellent potential for beneficial collaboration between responsible avocational archaeologists—those fitting the definition of an RRS—and professionals. Collaboration between RRSs and professional researchers is not new. Numerous published case studies (Evans et al. Reference Evans, Arzigian, Jean Dowiasch, Koldehoff and Loebel2018; Jones Reference Jones2019; Lovis Reference Lovis2018; McElrath et al. Reference McElrath, Emerson, Evans, Boles, Loebel, Nolan and Reber2018; Pike et al. Reference Pike, Meeks, Anderson and Ellerbusch2006) illustrate the benefits of collaboration between collectors and professionals. These collaborations are often the important event that defines whether the data associated with collections become part of our understanding of the archaeological record or are lost forever as the collection simply becomes a box of curios in someone's garage found long after the living memory of their discovery has disappeared. Importantly, Pitblado (Reference Pitblado2014) not only discusses why collaboration can be positive but also provides key reminders about associated legal and ethical issues.

Several large privately generated collections have previously been accepted as donations to the OSA. As noted, the Keyes Collection is the earliest, largest, and most significant collection of archaeological materials from Iowa gathered by an individual for which high-quality provenience information and associated documentation are also available. Keyes began his career as an avocational but later became a professional archaeologist in addition to having a career as a professor of German at Cornell College (Doershuk and Cordell Reference Doershuk, Cordell and Means2013). Several other large named collections with significant research potential rivaling the Keyes Collection are also curated at the OSA, including the Paul Sagers Collection (275 sites, 16,328 artifacts; Cordell et al. Reference Cordell, Green and Marcucci1991) and the David Carlson Collection (92 sites, 63,680 artifacts; Carlson Reference Carlson1979; Lensink Reference Lensink2009). Both Sagers and Carlson, like the Palmquists and Keyes in his formative years, meet the definition of an RRS.

John Palmquist diligently worked at creating the necessary metadata to add research value to his collection, but it was apparent that simple transfer into the State Archaeological Repository was not just a matter of a transfer agreement. As is also true for many avocational collectors (and even many professional archaeologists), field projects are often “in progress” for extended periods, and there are always loose ends that need to be closed out. An integral part of the project success turned out to be time spent together in the field by Palmquist and OSA project archaeologist Warren Davis collecting additional locational data. Palmquist's decision to donate precipitated his getting the collection in order to a higher degree than its typical day-to-day condition, even as discussions began with OSA staff as how to best proceed.

GRANT SUPPORT AND CURATION STEPS

After several conversations, it was collaboratively established that funding was needed to facilitate the transfer and increase the long-term research impact of the donation. In the spring of 2018, the OSA pursued funding through the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs Historical Resources Development Program (HRDP) museum category grant program, which supports projects related—but not limited—to public education, cataloging, conservation, treatment of collections, artifact acquisition, interpretation of artifact collections, and exhibitions (Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs 2021). Awarded to the OSA on July 1, 2018, HRDP grant 201905-7002 was targeted for the Palmquist Collection. Project goals included artifact curation preparation, the updating of site records, and research. The HRDP funding was supplemented by student support funding from the ICRU program. A three-student team—consisting of Keeley Kinsella, Jacqueline O'Neill, and Maizy Fugate—worked closely with Warren Davis on the project during the 2018–2019 academic year under the general supervision of state archaeologist John Doershuk.

A modest grant by many standards, the $12,500 in funds received from the HRDP program was matched by slightly more than $6,000 generated through in-kind effort and ICRU student support. These funds proved critical as the catalyst for the successful transfer. John Palmquist was an active participant and collaborated in the grant activities; his effort was an important part of the cost-share match required as part of the award. Davis's time was substantially supported by the grant, but he also has invested many hours of his personal time and continues contact with the Palmquists. Doershuk, in his role as state archaeologist, was able to provide his project effort as cost-share match and authorized the waiving of curation fees associated with the donation. Student researcher support totaled $6,000 ($4,000 grant funded, $2,000 match from ICRU). Simply put, without the support received and effort expended, the donation of the Palmquist Collection could not have been responsibly handled by the State Archaeological Repository and certainly would not have provided the many positive outcomes it did.

A weeklong field trip was undertaken by Davis in late summer 2018 to initiate the project. A key first step involved documenting the status of the collection and assessing preparation needs, including details about the initial transfer of Palmquist's collection from his home in Stanton, Iowa, to the OSA in Iowa City. Additional trips by Davis were undertaken in December 2018 and August 2019 to record site details for several locations more recently found by Palmquist, as well as to transport additional donated artifacts to the OSA for curation.

The capstone step, curation preparation, was supervised by then OSA research collection director John Cordell and collection assistant Seraphina Carey, with the assistance of the ICRU students and Davis. As with all collections reposed at the OSA, the donated Palmquist Collection was integrated into the State Archaeological Repository following established guidelines (University of Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist 2017) and OSA implementation of widely used best practices (e.g., Buck and Gilmore Reference Buck and Gilmore2010; Malaro and DeAngelis Reference Malaro and DeAngelis2012; Merritt Reference Merritt2008; Reibel Reference Reibel2008; Simmons Reference Simmons2018; Swain Reference Swain2007; Trimble and Farmer Reference Trimble, Farmer and McManamon2018). The collection was organized by site number, and each site was assigned a unique accession number in the OSA's curation system. Artifacts were labeled with acid-free paper tags that coded site and provenience information, and they were bagged with paper specimen tags that included artifact descriptions. Although application of specific curation methodology to the Palmquist Collection is not the focus of this article, the above details are mentioned for the sake of completeness so that the important steps integrating the Palmquist Collection into the State Archaeological Repository are fully identified.

PALMQUIST COLLECTION RESEARCH POTENTIAL

The John and Phil Palmquist Collection comprises approximately 860 artifacts from 26 precontact sites, all of which were recorded by John or Phil. Of these, 19 sites are in John's native Montgomery County, whereas seven are from nearby Page County. Notably, this represents materials from approximately 12% of all known recorded sites in Montgomery County.

The sites from which artifacts in the Palmquist Collection were derived were investigated largely through surface collection. As a result of this surface collection strategy, most of the sites represented in the Palmquist Collection are multicomponent, with artifacts from several time periods present from mixed surface contexts. It is possible that standard archaeological survey methods during typical CRM archaeology projects may have produced a larger number of more spatially discrete sites in these locales. However, considering the disturbance from agriculture in such deeply dissected river valleys, it is also entirely possible that sites would have still been recorded as large, multicomponent scatters. Ultimately, it is our opinion that it is better for these sites to have been recorded imperfectly than left unrecorded while waiting for full-scale professional survey that the collection area likely may never see.

Sites were recorded by John or Phil Palmquist on paper USGS topographic maps. Most of the donated collection was associated with sites that had been previously recorded by them beginning in the 1980s on standardized ISF paper forms. This means that because the bulk of the collection had preexisting assigned site numbers, John was able to keep the majority of the collection organized accordingly, even as he revisited sites and collected additional artifacts. This left comparatively few archaeological materials for the OSA to organize and to which to assign new site numbers. The locations of these newly recorded sites were also marked by the Palmquists on USGS topographic maps, with handwritten notes recording details of the location, making for easy inclusion into the ISF.

The majority of sites were located in agricultural fields mostly located in steep uplands and on late Wisconsinan loess-mantled terraces, all overlooking well-defined streams and terraces of Holocene age. A small number of artifacts from the collection were also recovered either eroded from banks or in sandbars. These deep, well-defined valleys are characteristic of southwestern Iowa, and they include both major-order rivers such as the East and West Nodaway, the East and West Nishnabotna, and John and Phil's native Tarkio River valleys, as well as numerous lower-order streams. Although these environs certainly would have had an appealing combination of attributes for ancient peoples, the steep hillslopes have been prone to erosion and runoff from agriculture practices employed after European settlement. Some sites were found located as scatters atop upland summits, but most of the artifacts—including the majority of ground stone tools—were recovered from sites on low terraces closer to waterways. Archaeologists with Luther College (Decorah, Iowa), guided by John Palmquist's observations from collecting, have hypothesized that occupation of the Tarkio River basin was seasonal, with winter camps along the low terraces and summer hunting camps occupying the uplands overlooking the valley (Henning Reference Henning1986).

Owing to southwestern Iowa's location on the margin between the Great Plains and the Eastern Woodlands, the Palmquist Collection includes artifact types known to not only a wide geographic area but one with impressive time depth. This includes seven Late Paleoindian projectile points collected by John and Phil, among which are two Agate Basin points, two Hell Gap points, a Milnesand point, an Eden or Scottsbluff point, and three Dalton points (Morrow Reference Morrow1984). A Dalton adze was also recovered. These locations are significant because there are few Paleoindian sites in Iowa recorded with similar locational precision.

Materials diagnostic to other time periods are also represented in the Palmquist Collection. This includes Archaic, Woodland, and late precontact (possibly Oneota) artifacts. It was noted by both John Palmquist and the project researchers that artifacts from the Late Archaic period seem especially well represented, suggesting more intensive use of the Tarkio basin during these times. This compares favorably with known Late Archaic site distribution in north-central Missouri, which favors similar riverine environments (Alex Reference Alex2000:73; Reid Reference Reid1980). Future work in the collection area, including testing of sites recorded by the Palmquists, may help confirm this. Across all time periods, the majority of the chipped stone tools consist of local varieties of Pennsylvanian chert common to southwestern Iowa (Reid Reference Reid1984) and surrounding portions of adjacent states.

Late precontact chipped stone artifacts are limited to three small flake arrow points likely reflecting Oneota Tradition usage of the area. These style points are not well known in southwestern Iowa but are relatively common in Oneota site assemblages elsewhere in Iowa and neighboring states, including Kansas, Nebraska, and Minnesota (Henning Reference Henning and Wood1998). Oneota Tradition sites are ancestral to the Ioway, Oto, Ponca, Omaha, and related tribes (Schermer et al. Reference Schermer, Green, Zimmerman, Forman and Lillie2015). The presence of these late precontact artifacts, even in limited quantities, suggests continuation of at least seasonal utilization of the area from earlier times.

The variety of chipped stone artifacts from mapped sites is notable, but perhaps the most impressive aspect of the Palmquist Collection is the number of pipestone items included in the donation—a total of 17 artifacts. This is more than five times the number of pipestone artifacts previously recorded in the State Repository as having been provenienced from southwestern Iowa. These items consist of jewelry of likely late precontact (perhaps Oneota Tradition) origin, such as beads and pendants, as well as a possible broken figurine and less formally worked items including minimally modified slabs. No pipes or pipe preforms were recovered by John or Phil Palmquist. Only a few pipestone artifacts have previously been found in southwestern Iowa: a single pipe at a Nebraska-phase earth lodge (13ML130) at the Glenwood locality in Mills County (Hedden Reference Hedden, Bollwerk and Tushingham2016) and a large pipestone slab excavated in 1988 from the Late Archaic McCall (13PA38) site in Page County (Mehrer Reference Mehrer1989)—a site suffering significant ongoing erosion damage that the Palmquists have been involved with monitoring.

The fact that these pipestone artifacts were recovered via surface collection limits precision in assigning cultural affiliation or time period for many of these pieces. However, use of nondestructive chemical analysis to determine the raw material origin of these pipestone artifacts can nonetheless help illustrate the utilization or movement of pipestone across the region, clearly demonstrating the research value of a properly documented RRS collection. Previous research has indicated that various pipestone sources from the midcontinent and eastern Great Plains have unique chemical signatures that are markers for geologic origin (Emerson and Hughes Reference Emerson and Hughes2000; Emerson et al. Reference Emerson, Hughes, Hynes and Wisseman2003, Reference Emerson, Hughes, Farnsworth, Wisseman and Hynes2005; Fishel et al. Reference Fishel, Wisseman, Hughes and Emerson2010; Gundersen Reference Gundersen2002; Hadley Reference Hadley2017). The 17 pieces of pipestone from the Palmquist Collection, as well as the pipestone slab excavated from McCall, were recently sent to specialists affiliated with the Illinois State Archaeological Survey. These artifacts were scanned using a portable infrared mineral analyzer (PIMA) device in order to measure quantities of trace minerals, after which these measurements were compared to a database of spectral values of both known pipestone outcrops and artifacts from other archaeological sites.

Although preliminary and the subject of ongoing investigation, the initial report of the PIMA suggests that of the 18 pipestone artifacts tested, nine match the chemical signature for “Kansas pipestone,” a term for pipestone derived from till or gravel sources in the area from southwest Iowa into eastern Kansas. This indicates a likely local origin for these artifacts. Several pieces of jewelry, including beads and pendants, are included in this category. Interestingly, an additional six pipestone artifacts appear to originate from two sources in Wisconsin (Barron and Baraboo localities), and another matches the signal of a pipestone artifact recovered from a site in the Cahokia area. Surprisingly, none of the pipestone artifacts subject to PIMA were a match for sources from Pipestone National Monument, despite the relatively short distance between that source and southwest Iowa. These preliminary results help reinforce that despite the general paucity of recorded archaeology in southwestern Iowa, inhabitants of the region were very connected to populations across the broader Plains and Midwest. A more complete report of this chemical analysis will be published in a future article.

DISCUSSION

An archaeological issue of considerable international importance and ongoing debate is how responsible curation of significant archaeological materials is to be handled (Childs and Warner Reference Childs and Warner2019), including how to ensure future public access in the face of the increasing monetary value that segments of our society are placing on certain artifacts. The focus on the dollar value of archaeological artifacts tends to heavily reinforce looting and a general disregard for context, which means that the research value of looted sites is greatly diminished. There are also strong incentives to not record the provenience of artifacts because doing so may create an evidence record of illegal collection. These facts greatly complicate interactions between professional and avocational archaeologists, but useful guidance for navigating these relationships can be found in the recent SAA "Statement on Collaboration with Responsible and Responsive Stewards of the Past" (SAA 2018): “With this document, the SAA encourages collaboration between archaeologists and ‘responsible and responsive stewards’ in ways that do not conflict with the professional ethical principles and codes that archaeologists have pledged to uphold.” Importantly, the emphasis focuses not on professionals versus avocationals but rather responsible collecting versus irresponsible collecting.

The acquisition through donation of the John and Phil Palmquist Collection by the OSA, as well as the collaborative relationship developed with John Palmquist over the past several years, serves to illustrate the benefits of meaningful collaboration between RRSs and professional archaeologists. At the most elementary level, the reporting of sites to the OSA by the Palmquists is itself an important service. The IAS Site Surveyor certification that John Palmquist earned in 1977 is clearly an early example in Iowa of RRS–professional collaboration. This certification program aims to provide the necessary training for avocationals to report their findings to the OSA and take an active role in the recording of high-quality archaeological data. Based on the number of sites John and Phil Palmquist have found in an otherwise undersurveyed region of Iowa, this can be seen as a clear success.

John Palmquist's role in the donation of the physical collection itself also cannot be overstated. His decision to donate his collection was not made lightly. However, by doing so, the process of acquiring the collection went more smoothly than it might have otherwise. As noted previously, many collections are offered years after the passing of their collector. The relatives of the collector often have little understanding of the context of the artifacts or their collection history. Even collections properly separated and organized may be inadvertently thrown into one box for convenience or separated because the “most interesting pieces” are removed from what is judged to be more mundane. In short, there are few ways to preserve the context of a collection—but many ways to lose it. Future research of materials in the Palmquist Collection, whatever this may entail, will benefit from the care and attention John and Phil Palmquist placed in preserving the collection's context and John's direct participation in the transfer of knowledge.

Funding is perhaps the largest hurdle to overcome in RRS–professional collaboration. Generally, there is regrettably little money available for any step of the process, be that for transportation, analysis, or final curation. Curation cost is especially problematic. Whereas volunteer labor can be used in a pinch to help facilitate the acquisition and analysis of a collection, curation fees are a real, long-term cost that must be generated. The successful acquisition of the Palmquist Collection was facilitated through the use of an HRDP grant from the Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs, whereas the ICRU grant from the University of Iowa helped fund the time of undergraduate students in the analysis and preparation of the collection for curation. In lieu of any dedicated funding source, such as a targeted endowment set aside specifically for supporting collection donations—a challenging though desirable goal for any repository to pursue—a combination of small-scale funding sources may be the most practical way for future RRS–professional collaborative projects to see successful fruition.

There are certain shortcomings that result from working with any collection of artifacts not from a professionally conducted survey or excavation. To an extent, this is true for the John and Phil Palmquist Collection, despite the relatively well-recorded locational data and information available from the collector. Specifically, the majority of sites recorded by the Palmquists remain untested, either via research by academic archaeologists or for purposes of assessing eligibility for the National Register of Historic Places. For this reason, intrasite information related to depositional integrity, the presence of features, and spatial patterning of artifacts within these sites is limited. With that said, it should be noted that archaeologist–collector collaboration is not intended to be a substitute for the work of professional archaeologists but as a way to obtain supplementary data and relate the information gathered by RRSs to the existing archaeological record.

CONCLUSIONS

As argued in the grant application to support donation and curation of the Palmquist Collection, there are four communities that have been directly and positively impacted by this effort. In addition, there has been the general benefit to all Iowans from the transfer of materials from private hands to the State Archaeological Repository, where all have access. The specific communities include professional researchers in archaeology looking for comparative data, Iowa state and local government agencies responsible for recording and managing archaeological site data, Indigenous and other descendant communities of Iowa whose material culture is preserved, and avocational researchers in archaeology whose behavior as responsible and responsive stewards has been positively reinforced.

We see our project as a valuable case study for other professional archaeologists to consider in their efforts to encourage responsible collecting and the ultimate curation of collections generated by RRS citizen-scientists in their areas. This project will ensure that artifacts and associated documents carefully collected and compiled by John and Phil Palmquist over their long careers as avocational archaeologists and Iowa Archeological Society members will be widely available and preserved for future generations. The Palmquists’ archaeological work stands as a credible model for other avocational archaeologists. Most significantly, it demonstrates the research value of maintaining a set of records about places visited and the artifacts collected at these places. This documentation means that these objects retain considerable research significance that can be fruitfully utilized in future comparative studies. This fits the needs of at least one tribal official, who recently articulated the importance to his tribe of learning about archaeology, not just from those in professional roles but also from collectors, especially those characterized as “good” collectors: “The good collectors are ones who recognize what they collect is part of someone's heritage and they care or at least think about those connections” (Alan Kelley, Deputy THPO for the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, personal communication 2021). This is certainly descriptive of the Palmquists.

The Palmquist Collection perfectly illustrates why collections from ethical, involved members of the public matter. Although surveys by archaeologists performing research for academic pursuits or CRM archaeology projects remain vitally important, there are many places in Iowa and elsewhere that are still understudied by professionals for various reasons despite their known archaeological potential. Donations such as that of the John and Phil Palmquist Collection help professional researchers gain a better understanding of an area's or region's material record and fill gaps in archaeological understanding. Perhaps more importantly, the story of this collection can serve as a model for how professional and avocational archaeologists can productively engage with one another for the betterment of everyone.

Our experience leads us to strongly reject the assertion that collaboration with ethical, responsible collectors in any way condones unethical behavior or incentivizes collectors. In our opinion, it is the continued reluctance of archaeologists to regularly engage with RRSs that perpetuates the worst of collector behavior. Indeed, engaging and encouraging ethical, responsible collectors and stewards of archaeological sites is imperative if archaeologists wish to engage and educate the public successfully. It is clear that despite the preference of the profession, the majority of the discoveries of archaeological sites will remain in the hands of nonprofessionals, which makes professional mentoring of RRSs a primary ethical responsibility. Only in this way will information associated with sites known to the public but unknown to professionals be systematically recorded. Simply put, there is no downside to professional archaeologists having a relationship with engaged, educated members of the public willing to be allies in the stewardship of the past.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bonnie Pitblado for her invitation to participate and her encouragement during the preparation of this article, and we thank the anonymous reviewers for their many valuable recommendations that have improved our presentation. Thanks to the many landowners who willingly cooperated with John and Phil Palmquist's requests for access for surface collection and retention of discovered artifacts. We are especially grateful to Thomas Emerson and Randy Hughes for their timely PIMA analysis of the pipestone artifacts. We also thank University of Iowa Research Experience students Keeley Kinsella, Jacqueline O'Neill, and Maizy Fugate for their hard work prepping the Palmquist Collection for permanent curation in the State Archaeological Repository and for their successful participation in the 2018 UI Spring Undergraduate Research Festival, where they expertly presented a poster describing their research work based on the collection. Student support was in part made possible by the ICRU (Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates) at the University of Iowa, and State Archaeological Repository of Iowa staff members Seraphina Carey and John L. Cordell provided knowledgeable mentoring to these students. Angela Collins and Teresa Rucker assisted with figure preparation, and Diego Hernandez and Lily DeMars provided the Spanish-language abstract. Mark Anderson and Daniel Horgen provided useful input on lithic typology and raw materials, as did Joseph Tiffany and John Hedden for the ceramic artifacts. The Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs provided project funding via a Historical Resource Development Program (HRDP) grant (201905-7002). No permits were required to conduct the work reported on in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this article and additional information about the John and Phil Palmquist Collection are available through the State Archaeological Repository of Iowa, maintained by the University of Iowa Office of the State Archaeologist. Contact Archivist Teresa A. Rucker (teresa-rucker@uiowa.edu or 319-384-0732).