In his dauntingly magisterial A Bibliography of the English Printed Drama to the Restoration, whose four volumes appeared between 1939 and 1959, W.W. Greg declared Fulgens and Lucrece (1512–16?) to be the first drama printed in England. Not until the 1530s, however, as Greg’s “Order of Plays” reveals, were dramatic texts printed regularly, although hardly frequently. The opening of the first public theatres in London in the 1570s created additional demand for printed drama, with a greater outpouring of published texts in the 1590s, coinciding with the Elizabethan playhouse in its noonday fullness.Footnote 1 The publication of drama in quarto continued until its rapid decline following the suppression of the theatres by the Puritans in 1642, well after elaborate folio editions had been published of works by Ben Jonson (1616) and William Shakespeare (1623), while that for Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher (1647) appeared a few years later, reflecting the popularity of play reading during the Interregnum. Folio editions, as is well known, were large luxury items designed as permanent additions to the private libraries of elite collectors and readers. Most of the hundreds of plays that were printed in early modern England appeared in smaller, cheaper, and more perishable quartos, about the size of a modern paperback.Footnote 2

The expanding corpus of printed drama in the Tudor and Jacobean periods raised questions of bibliographic control: What information about these texts was important? How would it be recorded and organized? Who would access it? Not that these questions were answered quickly. Other than the compilers who prepared lists integral to the collected works of the few playwrights published in folio, no one bothered to catalogue dramatic texts until 150 years’ worth of them had accumulated. Indeed, the oldest surviving list of plays (although neither prepared nor subsequently used as such) can be found dispersed throughout the most famous document of the Elizabethan theatre, Philip Henslowe’s Diary. Spanning the years 1591−1609, the Diary includes the names of 297 plays among its various entries, mostly in Henslowe’s hand, about performances by the Admiral’s Men. Ironically, this unintentional first collection of play titles served as a record of playhouse repertoire, not literary production. And although Henslowe’s Diary remains the foremost piece of material evidence for the reconstruction of theatrical performance in late-Tudor England, it was not fully available to scholars until 1845, when the Shakespeare Society published John Payne Collier’s transcription of the original manuscript at Dulwich College in south London, complete with the roguish editor’s forged interpolations.Footnote 3

The earliest-known informal lists of printed plays, as distinct from playhouse records like Henslowe’s Diary or the publication registers kept by the Stationers’ Company, were drawn up by two book collectors in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The courtier Sir John Harington (1561–1612) and the poet Henry Oxinden (1608–70) maintained inventories of printed dramatic works that they owned.Footnote 4 Among Harington’s papers, now in the British Library, can be found a single folio leaf written on both sides in his hand naming every play text in his library, such texts collected into eleven bound volumes.Footnote 5 Like most collectors Harington did not bind individual plays (quartos, being slim, were sold unbound) but waited until he had a sufficient number that together could form a bound volume. His erratically and sometimes erroneously formatted list contains 168 titles, the earliest of which is the Tudor interlude Lusty Juventus (c. 1565), but more than half of which date from 1600 to 1609, including slightly more informative entries for The True Chronicle History of King Leir (“King Leire: old”) and Westward Ho (“Westward hoe T. De. web. I.”).Footnote 6 Henry Oxinden of Barham, Kent, also catalogued the 122 play texts in his private library, the handwritten list occupying but a single page in his vast commonplace book, the document’s length and placement suggesting its casual ordinariness. The list was compiled no later than 1665, but it reflected a collection formed decades earlier, because the latest text mentioned dated from the 1640s. Oxinden appears to have stored individual play texts in boxes or other containers because he divided them into groups of between sixteen and twenty-five, too large a division for the bound volumes that Harington preferred.Footnote 7 Both lists, though, were haphazard, with authors and publication dates provided for only some plays and not always correctly.

The lists drawn up by Harington and Oxinden were private documents for private collections. As such, they were neither transcribed nor studied until the late Victorian era, and there is no evidence that any theatre scholar before William Carew Hazlitt and Robert Lowe in the late nineteenth century used those lists or knew they existed. Yet if nothing else, these two documents provide firm evidence that serious collectors of plays were an established species when Shakespeare and Jonson wrote for the stage.Footnote 8 Serious collectors – that is, the sort who knew that King Lear was based upon King Leir and regarded that fact significant enough to set down in writing – needed to know what titles were available to purchase, particularly secondhand ones. Traditionally, such information was supplied by booksellers in person at their shops, where they carried a varied stock of new and used titles, but eventually, the same information appeared in printed sale catalogues – publicly available documents – the oldest of which in England dates from 1595. It is those sale catalogues, I want to argue, that created the initial textual space out of which theatre history emerged alongside literary history.

“An exact and perfect Catalogue of all the Playes that are Printed”

The first known catalogue entry for a play dates from 1618, when, five years before he published the First Folio, William Jaggard included the following entry in his Catalogue of such English Bookes, as lately have bene and now are in Printing for Publication: “The marriages of the Arts, a Comedy acted by the Students of the Church, written by Barton Holliday, Master of Arts, printed for Iohn Parker.”Footnote 9 Jaggard’s catalogue was a comprehensive list of new and forthcoming works, and thus included both dramatic and nondramatic texts, ranging from stage comedy to divinity to fishery. It served not merely to advertise works for sale (or resale) but to defend the rights of printers by underlining his sole claim to the enumerated texts, thus warning off potential copyright infringers at a time when hazy definitions of intellectual property made literary piracy commonplace.Footnote 10

Recognizing the specialized tastes of their customers, some stationers eventually prepared catalogues or advertisements devoted exclusively to dramatic works and printed them as integral to published play texts.Footnote 11 Such catalogues, aiming at comprehensiveness, purported to give the titles of all plays printed to date – and not just the available stock of the particular London bookseller who prepared the catalogue – and eventually supplied authorship attributions and genre labels. The often-careless compilers transcribed information from title pages only, working quickly through accumulated stock. The earliest such catalogues date from just before and just after the Restoration and are known by the surnames of the publishers whose wares they itemized: Rogers and Ley (Reference Rogers and Ley1656), Archer (Reference Archer, Massinger, Middleton and Rowley1656), and Kirkman (Reference Kirkman1661, expanded 1671).Footnote 12

Richard Rogers and William Ley included “An exact and perfect Catologue [sic] of all Playes that are Printed” in their publication of Thomas Goffe’s tragicomedy The Careles Shepherdess.Footnote 13 Far from being an afterthought, the playlist merged with the book, for it was referenced on the title page (“an Alphabeticall Catologue of all such Plays that ever were Printed”) and took up the volume’s first six pages. Though no explicit offer of sale was made, the logic of the document suggested that it was based upon Rogers and Ley’s stock of 505 printed plays. Plays were listed alphabetically but only to the first letter – Roaring girle, or Mol cutpurse precedes Richard the 3. Yet the alphabetical order was then compromised by a rough attempt at chronology, with works before 1616 (the year of Shakespeare’s death) tending to be listed first under each letter. Not that any publication dates were provided. Authorship attributions were sporadic and sometimes incorrect (Shakespeare apparently wrote Edward II, while no author is named for Hamlet, Prince of Denmark), no information was provided on genre, and there were some duplicate entries.Footnote 14 Nevertheless, Rogers and Ley’s list provided a baseline standard for future play catalogues, bracketed some plays according to chronology, and remains the earliest surviving document of a thriving trade in secondhand printed drama.Footnote 15

Later that same year, the stationer Edward Archer appended “an exact and perfect Catalogue of all the Playes, with the Authors Names … more exactly Printed then ever before” to his publication of Massinger, Middleton and Rowley’s comedy The Old Law.Footnote 16 This catalogue was clearly indebted to the one prepared by Rogers and Ley, most obviously because it repeated errors and corrected duplicate entries from the earlier work, while also managing to introduce new errors of its own. Yet there were improvements: More than one hundred additional plays were listed, bringing the total to 622; authorship attribution was standard; and for the first time, genre indications were included for each play: “T” for Tragedy, “C” for Comedy, and so on.Footnote 17 As in Rogers and Ley, plays were listed alphabetically only to the first letter, no dates were supplied, and chronology was merely hinted at through groupings of the earliest plays. Despite more consistent authorship attribution there was little effort to bring together plays by the same dramatist under each letter heading, suggesting that the catalogue was prepared for customers who collected individual plays in quarto and not the corpus of individual dramatists. Searching by author was the least efficient way to use this document.

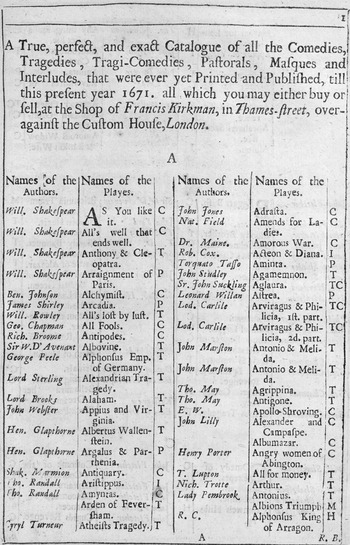

Five years later, the bookseller, publisher, collector, librarian, and minor author Francis Kirkman (1632–c. 1680) produced the most important of the Restoration playlists, appending “an exact Catalogue of all the playes that were ever yet printed” to his publication of the Tudor comedy Tom Tyler and His Wife.Footnote 18 The catalogue gives details of 685 play texts, sixty-three more than were listed by Archer. A decade later, in 1671, Kirkman printed an updated catalogue (Figure 2) explaining that “there hath been, since that time, just an hundred more [plays] Printed.”Footnote 19 He repeated his view that the initial 1661 list was complete for its time, with one minor exception: “I then took so great care about it, that now, after a ten years diligent search and enquiry I find no great mistake; I only omitted the Masques and Entertainments in Ben. Johnsons first Volume.”Footnote 20 With the addition of new and previously omitted works, the total number of plays in the 1671 list amounted to just over 800.

Figure 2 Francis Kirkman, “A True, perfect, and exact Catalogue…,” 1671, title page. Kirkman’s revised 1671 play catalogue was appended to a translation of Corneille’s Nicomède. Following Archer’s 1656 playlist, Kirkman mistakenly attributes George Peele’s court entertainment The Arraignment of Paris (1584) to Shakespeare.

Reassuring customers that his revised list was definitive, Kirkman pointed out that he had set eyes upon all but ten of the plays and possessed copies of all but thirty. If correct, Kirkman’s tally of ownership made him the foremost collector of pre-Restoration English printed drama and thus uniquely placed to become its chief archivist. Having acquired his comprehensive stock, Kirkman underscored the list’s commercial purpose, informing customers that they could both buy and sell secondhand play texts at his shop or at those of three other London stationers who were his partners. A good salesman, he was both selling and replenishing his inventory. And so the fully informative header to the 1671 list was addressed both to purchasers and suppliers – who might well be the same person, since individual collectors could both buy and sell books.

Kirkman showed greater initiative than his predecessors, for his catalogue was the most elaborate of the three. Authorship attributions were nearly universal and genre designations were more precise than in Archer, yet plays were still alphabetized only to the first letter. Kirkman eliminated nearly all duplicates from the prior lists, an accomplishment, as Greg argues, that demonstrated “some real familiarity with the plays in question.”Footnote 21 This time the publisher worked methodically, comparing one text with another. In consequence, he was in command of his inventory.

Kirkman boasted repeatedly of his familiarity with the full corpus of printed drama, not just in his catalogues, but also in the plays that he published around the same time. In 1661 his first published play was Webster and Rowley’s Cure for a Cuckold, a late-Jacobean comedy that had never been printed. Publishing a work that existed only in manuscript four decades after its first performance might be thought sufficient evidence of Kirkman’s intimate knowledge of dramatic literature. Lest, however, there be any doubt on the matter, the stationer penned a letter “To the Judicious Reader” in which he set out the full dimension of his accumulated expertise and then explained how that expertise translated into an unparalleled commercial opportunity:

I have been (as we term it) a Gatherer of Plays for some years, and I am confident I have more of several sorts than any man in England, Book-seller, or other: I can at any time shew 700 in number, which is within a small matter all that were ever printed. Many of these I have several times over, and intend as I sell, to purchase more; All, or any of which, I shall be ready either to sell or lend to you upon reasonable Considerations.Footnote 22

Later that year, in his edition of The Thracian Wonder, Kirkman issued a similar advertisement, informing customers that “if you please to repair to my Shop, I shall furnish you with all the Plays that were ever yet printed. I have 700 several Plays, and most of them several times over, and I intend to increase my Store as I sell.”Footnote 23 Such comments obviously articulated with the playlist that Kirkman compiled that same year, 1661, all of which emphasized his deep and longstanding knowledge of dramatic history. Still broader attestations formed part of the revised and updated 1671 list, with Kirkman, a blacksmith’s son, confirming that he has “been these twenty years a Collector of them [plays], and have conversed with, and enquired of those that have been Collecting these fifty years.”Footnote 24

The reference to other collectors and to the longevity of their collections is an important marker for an emergent sense of historicity in Kirkman’s playlists and commentary. No doubt it was the publisher’s familiarity with the history of the drama – acquired mostly by amassing a collection of more than 700 works, but also by placing himself within a network of veteran collectors – that led him to abandon the vague incomplete chronology of the earlier lists. In its place, he introduced a new way of ordering plays: by a hierarchy of dramas and dramatists. For the first time, explicit (but uncontroversial) judgments were issued about which plays and playwrights mattered most in a document whose stated purpose was to list and to attribute the entire corpus of printed drama. These judgments were the archivist’s equivalent of establishing a preferred playhouse repertoire.

In the original 1661 playlist, Kirkman placed immediately under each letter the relevant plays that appeared in the three folio editions, grouped by author and always in the same order – Shakespeare, Fletcher, and Jonson. Other works attributed to the three main dramatists appeared further down the list, interspersed among the plays written by all other authors. This hybrid format – organization partly by title and partly by author – embodied a tension between the catalogue’s immediate marketplace need to advertise the titles of commodities for sale and its longer-term ability to shape the dramatic canon by privileging a handful of authors. The impulse to judge was inherent in the catalogue format itself. In the revised 1671 version Kirkman went farther, explaining his canon-forming principle of emphasizing the achievements of the ten most prolific dramatists, beginning with Shakespeare, whose collective works totaled more than a third of the dramatic corpus to date.Footnote 25

“I have had so great an Itch at Stage-playing”

Literary scholarship understands Restoration playlists, and especially Kirkman’s, as vehicles for the consolidation of authorial importance and identity. As Jeffrey Masten has observed, these lists “trace the rising (though still tentative) importance of authorship as a visible category for organizing printed drama.”Footnote 26 Certainly that is true; but there is more to say. From a historiographical perspective, Kirkman’s “Advertisement to the Reader,” which explained his “better method” of organizing information, was more significant than his canon-forming playlist – giving pride of place to Shakespeare, Jonson, and Fletcher had become the norm well before 1671 – because it brought a theatrical outlook to the entire enterprise.

Such outlook was no doubt spurred by the reopening of the playhouses a decade earlier with the restoration of the Stuart monarchy.Footnote 27 Before the Civil War, acting companies had generally been reluctant to allow the plays they owned to appear in print for fear of equipping their competitors. After 1660, however, and with the creation of the patent duopoly, the newly established companies – the King’s Company under Thomas Killigrew and the Duke’s Company under Sir William Davenant – were eager to see plays printed and to take advantage of the publicity generated by the format while retaining sole production rights. It quickly became standard for a new play or a revived old one to be promptly published. In 1668, Edward Howard, in the preface to his tragedy The Usurper, remarked that “the Impression of Plays is so much the Practice of the Age, that few or none have been Acted, which fail to be display’d in Print.”Footnote 28

The fresh abundance of printed drama in the Restoration, a supply that met increased demand, enabled Kirkman to address his customers (in his “Advertisement”) not in a businesslike manner but in the more fraternal spirit of one play-collector talking to another. Deliberately, he made himself the equal of his readers, careful not to impose upon them his own judgments. “I shall not be so presumptuous,” he soothingly demurred, “as to give my Opinion, much less, to determine or judge of every, or any mans Writing, and who writ best.” Demurrals notwithstanding, he speedily abandoned any critical reticence by declaring Thomas Meriton the “worst” English playwright.

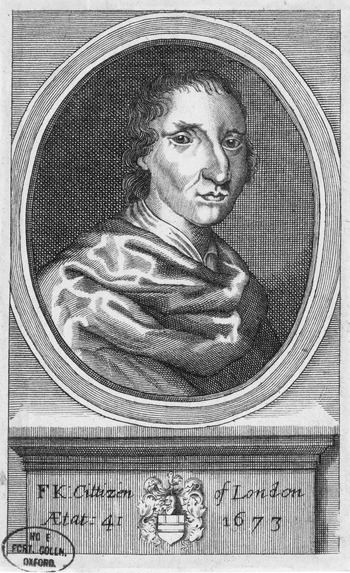

Still, Kirkman (whose portrait is shown in Figure 3) needed to come across not as a money-grubbing bookseller but as a true expert on the drama: someone “having taken pleasure to converse with those that were acquainted” with “all the old Poets.” He accomplished that self-fashioning by displaying theatrical knowledge: not just scripts and the circumstances under which they were published, but their life on the stage and the playhouse environment for which they were originally written. In other words, Kirkman introduced knowledge of stage history into a document whose immediate purpose was to sell copies of printed drama precisely because he believed that such knowledge would appeal to book collectors.

Figure 3 Portrait of Francis Kirkman from his autobiography The Unlucky Citizen (Reference Kirkman1673). Bookseller and prodigious collector of pre-Restoration drama, Kirkman (1632–c. 1680) was also an incipient theatre historian who confessed to an “Itch at Stage-playing.”

In the evocative passage quoted below, the publisher moved swiftly backward in chronology from print to manuscript to performance and, lastly – or, rather, firstly – to the primordial scene of a tireless, but alarmingly louche, “old Poet” at work, the foundational act of theatrical labor that set in motion the entire world of the stage:

Although there are but 806. Playes in all Printed, yet I know that many more have been written and Acted, I my self have some quantity in Manuscript; and although I can find but twenty five of Tho. Heywoods in all Printed, yet (as you may reade in an Epistle to a Play of his, called The English Traveller) he hath had an entire hand, or, at least, a main finger in the writing of 220. and, as I have been informed, he was very laborious; for he not only Acted almost every day, but also obliged himself to write a sheet every day, for several years together; but many of his Playes being composed and written loosely in Taverns, occasions them to be so mean.

Eager, perhaps, to parade his wide-ranging expertise, Kirkman commented at length upon a dramatist outside the “triumvirate of wit,” the exclusive club to which only Shakespeare, Jonson, and Fletcher belonged, and which the publisher himself repeatedly affirmed through the organizing principles of his own catalogues. By demonstrating keen knowledge of a lesser playwright such as Thomas Heywood – who practiced his craft “loosely in Taverns” – Kirkman signaled that his understanding of the dramatic form ran deeper than would be apparent from, say, a more predictable account of the Greek and Roman verses that inspired Ben Jonson. Moreover, by 1671 it was evident that revivals of Heywood did not broadly appeal to Restoration actors or audiences. This commentary relied on deeply specialist knowledge, and so testified to Kirkman’s mastery of the subject.

And yet there was more: something distinctive about Heywood and his career that suited Kirkman’s purposes. Among his contemporaries, Heywood stood out for grumbling about the printing of his works, complaining that he was too busy to revise them for publication. And thus Kirkman duly pointed out that not only were some of Heywood’s plays still in manuscript thirty years after the dramatist’s death, but that he himself possessed “some quantity” of them.Footnote 29 Moreover, Heywood’s creative output exceeded the manuscript and printed works that bore his name because he was involved in the composition of many more: “he hath had an entire hand, or, at least, a main finger in the writing of 220.” Kirkman was quoting nearly verbatim from Heywood’s letter to the reader prefacing The English Traveller (Reference Heywood1633), in which the dramatist maintained having had “either an entire hand, or at least a maine finger” in “two hundred and twenty” plays.Footnote 30 As Heywood further acknowledged, his “Playes are not exposed unto the world in Volumes” because some were lost through “shifting and change of Companies,” some were controlled by “Actors, who thinke it against their peculiar profit to have them come in Print,” and also because “it never was any great ambition in me, to bee in this kind Voluminously read.”Footnote 31

By drawing attention to Heywood’s career and writings, Kirkman signaled that any catalogue of printed drama – including his own – must by definition be false and incomplete. False because it concealed collaborative models of dramatic authorship and incomplete because it neglected the much larger number of works still in manuscript, to say nothing of printed works whose title pages either misrepresented authorial labor or omitted it entirely.Footnote 32 Having thus deconsecrated his own text (which promoted itself as “True, perfect, and exact”) Kirkman pushed his readers back, consciously and insistently, to moments that were rhetorically constructed as more truthful: playwriting, acting, and staging. The “Advertisement” began with Kirkman boasting of his catalogue’s authority – “after a ten years diligent search and enquiry I find no great mistake” – but ended with that very authority overturned – “I know that many more [plays] have been written and Acted.” He was right to hesitate: Just 40 per cent of the plays verified as having been staged between 1575 and 1642 were published at the time. For plays written for companies, who viewed publishing as an unwelcome invitation to competitors, the figure dropped to about 10 per cent.Footnote 33 It made sense, then, from a hermeneutic perspective, for the stationer to place his “Advertisement” at the end of the catalogue: Its purpose was not to deter anyone from using the catalogue (after all, Kirkman needed to stay in business) but rather to dissuade anyone from wrongly presuming that it represented the sum of dramatic knowledge. It served, rather, as an envoi, sending the reader on a new journey, but a journey back to the scene of playhouse origins.

Taken together, the overriding message of the catalogue and its post-script advertisement was that behind nearly every instance of printed drama – and, more significantly, behind the many more instances when a drama was not printed – stands a theatrical a priori. In this context, Heywood’s Apology for Actors – a defense of the stage not mentioned by Kirkman, but one which his audience of devoted collectors would have known, and perhaps had bought and read – exercised by implication a similar function, guiding the reader’s attention back to the corporeal liveness of the performance event, aurally epitomized by Heywood as “the applause of the Actor.”Footnote 34 In these various ways the publisher insisted that theatre history was native soil to dramatic literature, the ground from which the harvest of printed drama was sown and reaped.

Kirkman’s eccentric autobiography, The Unlucky Citizen (Reference Kirkman1673), reveals that his theatrical inclinations were neither a studied masquerade designed to appeal to prospective customers nor a stance antipathetic to collecting and reading printed drama. Though the following passage did not appear in print until after the publication of his two play catalogues, it recalled an early formative moment in the author’s life. During the hardship years of the Interregnum the young Kirkman was closely involved with the struggling theatre and possibly graced the illicit stage once or twice to satisfy his “Itch at Stage-playing”:

I studied my Pleasure and Recreation; the cheifest [sic] of which, and the greatest pleasure that I took being in seeing Stage Plays; I ply’d it close abroad and read as fast at home, so that I saw all that in that age I could, and when I could satisfie my Eye and my Ear with seeing and hearing Plays Acted; I pleased myself otherwise by reading, for I then began to Collect, and have since perfected my Collection of all the English Stage Plays that were ever yet Printed … And I have had so great an Itch at Stage-playing, that I have been upon the Stage, not only in private to entertain Friends, but also on a publique Theatre, there I have Acted, but not much nor often, and that Itch is so well laid and over, that I can content my self seeing two or three Plays in a Year.Footnote 35

Elsewhere in his autobiography, which covers only the first two decades of his life, Kirkman advised his readers not to “skip over” prefaces and dedicatory letters found in whatever books they were reading, because such texts make manifest “the intent and design of the Authour.”Footnote 36 He urged that “the Epistle and Preface” be “twice read over: both before and after the reading of the Book.” Such recommendation effectively theatricalized the act of reading, holding that experience between a stage-like prologue and epilogue. Meta-texts, whether in the form of prefaces or epistles dedicatory, help readers to better understand the main text just as prologues and epilogues, by directly addressing the audience, explain and provide context to a particular theatrical performance. All the more reason, then, for us to look closely at such materials written by Kirkman himself. What we will find is that such texts bracket the act of reading dramatic literature within an overall perspective upon theatrical history, thus reiterating the holistic work accomplished by his playlists.

At the start of his publishing career, and nearly a decade before he printed his first dramatic text, the twenty-year-old failed scrivener’s apprentice dedicated his translation of The Loves and Adventures of Clerio & Lozia (Reference Kirkman1652) to the actor and hardheaded theatrical producer William Beeston (c. 1606–82).Footnote 37 Son of the actor and producer Christopher Beeston, he had worked with his father at the Cockpit and the Red Bull, and thus he acquired an unusual amount of insider theatrical knowledge. During the Interregnum, William Beeston (unlike other actors) had remained politically neutral and persistently sought permission to stage plays at the Cockpit with his re-established “Beeston’s Boys,” an acting troupe comprised of apprentices and covenant servants. In 1652, the year of Kirkman’s dedication, he finally gained title to the remains of Salisbury Court, a theatre whose interior had been destroyed by a company of soldiers in 1649 when Beeston had made his first attempt to secure the premises.Footnote 38 Between 1652 and 1656, when Cromwell’s government renewed its suppression of theatres, Beeston staged plays at the rehabilitated Salisbury Court.

A redoubtable man of the theatre – Dryden later hailed him as “the chronicle of the stage” – and someone who persevered in the face of continued political opposition – William Beeston was an unlikely choice to be the dedicatee of an English translation of a French prose romance.Footnote 39 Kirkman, however, must have known what he was doing. What he did was to craft a dedication that anchored him firmly within the nostalgic theatrical tradition that, in Kirkman’s estimation, Beeston heroically preserved and embodied:

Divers times (in my hearing) to the admiration of the whol Company, you have most judiciously discoursed of Poësie: which is the cause I presume to chuse you for my Patron and Protector; who are the happiest interpretor and judg of our English Stage-Playes this Nation ever produced; which the Poets and Actors of these times, cannot (without ingratitude) deny; for I have heard the chief, and most ingenious of them, acknowledge their Fames & Profits essentially sprung from your instructions, judgment and fancy.Footnote 40

In this passage Kirkman recollected the immediate past of the pre-Civil War theatre, in which dramatists and performers could acquire wealth and renown. After Parliament’s main injunction against the theatres and the “Seasons of Humiliation” that followed, the outlook grew decidedly less auspicious.Footnote 41 Following the (not always successful) suppression of the theatres, as the anonymous author of The Actor’s Remonstrance observed, many performers were compelled to “live upon [their] shifts, or the expence of [their] former gettings, to the great impoverishment and utter undoing of [their] selves, wives, children, and dependants.”Footnote 42 Kirkman’s reference, moreover, to the “Poets and Actors of these times” – with whom, he claimed, he had conversed – carried the unmistakable overtone of safeguarding a tradition still under threat: “these times” contrasted sadly with the glory days before 1642. Kirkman allied himself to such determined acts of theatrical perseverance by dedicating a non-dramatic work to William Beeston.

More boldly still, Kirkman situated himself within playhouse confines, recalling the occasion – backstage, possibly, at Salisbury Court – when he joined the “whol Company” of actors in listening to Beeston “discours[e]” admirably on the drama. As if such blatant advocacy of performance history were not enough, Kirkman closed his dedication with an appeal to Beeston to adapt Clerio & Lozia for the theatre: “you will find much newness in the Story, worthy an excellent Poet to insoul it for the Stage; where it will receive ful perfection.”Footnote 43 Indeed it seems probable that if Kirkman did appear on the stage sometime around 1652, as he claimed, then it was likely under Beeston’s management at Salisbury Court. Crucially, Kirkman understood stage adaptation not as the translation of a text from one literary genre to another – romance to drama – but as something more transformative: the “ful perfection” of words through their animation on the stage; the metaphoric infusion of immortal soul (“to insoul”) into mortal body.

Kirkman’s Reference Kirkman1652 dedication of Clerio & Lozia imagined a life in performance that political circumstance would not permit for another eight years. Yet when the moment came he was ready. Soon after the return of the Cavaliers and the reopening of the theatres in 1660, and to meet the consequent heightened demand for dramatic works, Kirkman began publishing plays and advertising the stock of old ones that he had accumulated over the previous decade. In 1661 he entered into a partnership with the stationers Nathaniel Brook and Henry Marsh and with the printer Thomas Johnson. Within months he published four plays in quick succession: Webster and Rowley’s A Cure for a Cuckold and The Thracian Wonder, Gammer Gurton’s Needle, and J.C.’s A Pleasant Comedy of Two Merry Milk-Maids.Footnote 44 The marketing strategy, so to speak, for A Cure for a Cuckold rested on that previously unpublished work’s documented theatrical success in pre-Civil War times: “several persons remember the Acting of it, and say that it pleased them generally well.”Footnote 45 Kirkman’s address to the reader in The Thracian Wonder, also published in 1661, referred to the suppression of the theatres during the Commonwealth: “We have had the private Stage for some years clouded.”Footnote 46 Even in his preface to the Spanish chivalric romance Don Bellianis (Reference Kirkman and Fernández1673) Kirkman cited “the particular esteem of our late English stage Plays.”Footnote 47

Kirkman put that esteem to the test in 1673 by republishing and enlarging The Wits, a collection of the popular short comic pieces (or “drolls”) that during the Commonwealth were adapted from full-length plays and supposedly performed “by stealth … and under pretence of Rope-dancing.”Footnote 48 Kirkman and Marsh’s theatrically inclined and historically situated preface to their 1661 edition of Bottom the Weaver made clear what inspired them to print that text and how they believed it would be used:

[T]he entreaty of several Persons, our friends, hath enduced us to the publishing of this Piece, which (when the life of action was added to it) pleased generally well … [C]onsidering the general mirth that is likely, very suddainly to happen about the Kings Coronation; and supposing that things of this Nature, will be acceptable, [we] have therefore begun with this which we know may be easily acted, and may be now fit for a private recreation as formerly it hath been for a publike.Footnote 49

A droll was precisely the sort of work that lived only in performance and could not plausibly be read as literature. It could be read only as a prompt for the “life of action” added by the stage, exactly as its publishers understood. Whether in booksellers’ catalogues or a publisher’s prefaces and addresses, some printed drama of the period consciously aligned itself with stage history and repeatedly directed the reader’s attention back to the actualities of performance – not as the other of the printed text, but as its other self.

“As it hath been sundry times publickley acted”

Thus far in this chapter I have built outward from Restoration playlists, trying to reconstruct a network of interpretive documents that moves intuitively from printed drama and its bibliographic records to the circulation of theatrical memories, appraisals, and imaginings. Although I have begun that reconstruction by looking at play catalogues, I could just as easily have started with the plays themselves. In her seminal study Theatre of the Book 1480–1880, Julie Stone Peters reminds us that the first major development in the history of printed drama was the codification of typography that marked those texts as dramatic: speech prefixes, scene divisions, stage directions, and lists of characters. Spurred by the rise of professional theatres in England and throughout Europe in the mid-sixteenth century and by the simultaneous expansion of play readers, some of whom were also theatregoers, early modern printers took pains to distinguish drama from other literary genres (e.g., prose narratives, devotional works) whose page layout it initially, and confusingly, resembled.Footnote 50

Typographical distinctiveness was but the first development in how plays were printed in the early modern period. Widening the analysis that Peters has undertaken, we can see that the consequent development was an accommodation of the performance event within the format of printed drama: not the script alone, but also title pages, illustrations, prefaces, dedications, and addresses to readers. These images and paratexts could serve as detailed and topical theatrical markers by alluding to specific productions. By the late sixteenth century, printed drama began to engage – not always affirmatively, not always consistently – with the event of performance, whether historical, contemporary, or conjectural.Footnote 51

Engagement with performance is precisely what made some printed works conveyors of theatre historical information, sometimes in a straightforwardly factual manner (e.g., names of playhouses, acting companies, and actors,) but more often in an interpretive manner (e.g., accounting for the success or failure of a performance). Printed drama continued to fulfill its traditional function as entertainment for readers and listeners, but that hardly negated its new power to summon up and reflect upon performance and spectatorship. As the historiographer Ronald Vince pithily observed, “[t]he texts of Elizabethan plays obviously constitute an important source of information for the theatre historian.”Footnote 52 Theatre scholars have never been blind to that fact. Chambers knew it in the twentieth century, Collier knew it in the nineteenth century, Malone knew it in the eighteenth century, and Langbaine knew it in the seventeenth century. What they all knew was that the publication of an early modern play was simultaneously an act of theatre history by virtue of the publication’s ability to evoke life upon the stage

Apart from the play’s name, the only piece of information consistently included on quarto title pages was the name of the acting company who first staged the work. “As it hath been sundry times publickley acted” was the standard form of words, an assurance to readers that the published text was taken directly from the script used in the theatre.Footnote 53 A pre-Civil War dramatist, however, could be all but invisible in the publication of plays in quarto. True, the seventeenth-century folio editions of plays by Jonson, Shakespeare, and Beaumont and Fletcher were monuments to authorship; but they were highly conspicuous exceptions to the rule exemplified in the printing of drama in quarto: Plays were most strongly linked not to their authors but to the companies who performed them.

And so the title pages of plays in quarto tended to boast of theatrical success by including details of the company that first produced the play and the venue where it was performed, sometimes naming the lead actors. When A Knack to Know a Knave (1594) was printed a year or so after it was first performed by Lord Strange’s Men, the extended title gave all three pieces of information: A most pleasant and merie new Comedie, Intituled, A Knack to knowe a Knaue … as it hath sundrie tymes bene played by Ed. Allen and his Companie. With Kemps applauded Merriments.Footnote 54 Cast lists, a regular feature of plays published in the Restoration, began in the Jacobean era. About a decade after its initial staging, the 1623 publication of John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi included “The Actors Names” for thirteen roles, including all the principal ones.Footnote 55 It was the first printed cast list in the history of the English theatre. For the roles of Ferdinand, the Cardinal, and Antonio there are two lists: one for the original production and one presumably for a revival sometime after the death of Richard Burbage (the original Ferdinand) in 1619. In the same period, Massinger’s The Roman Actor (Reference Massinger1629) included a full cast list, with John Lowin as Domitanus Caesar and Joseph Taylor as Paris the Tragedian.Footnote 56 As Peter Holland has rightly observed, including casts lists within printed drama ensures that “the text performs part of the history of its own performances.”Footnote 57

More creatively, printed drama might include performance iconography. Very few such images appear prior to the 1730s, and they must be regarded more as tokens of performances than as precise visual representations.Footnote 58 In his Renaissance Theatre: A Historiographical Handbook, Ronald Vince considers three of the most famous illustrations in Jacobean and Restoration printed drama – the title-page vignettes of rear-curtained thrust stages in William Alabaster’s Roxana (1632), Nathaniel Richards’ Messalina (1640), and Kirkman’s edition of The Wits (1672, Reference Kirkman1673) – prudently reminding us that they cannot be regarded as trustworthy depictions of theatre interiors. Indeed the seven disparate characters assembled onstage in the frontispiece to The Wits – including Falstaff and the clown Bubble from John Cooke’s Greene’s Tu Quoque (acted at the Red Bull in 1611, printed in 1614) – confirm that the image does not derive from any specific performance. The picture’s referential laxity is further emphasized by the presence of footlights and candelabra: Both suggest an indoor theatre even though Kirkman’s preface mentioned the Red Bull in Clerkenwell, which was likely an open-air theatre, as a popular site for the performance of drolls.Footnote 59 Whatever performance this illustration depicts it is not, as G.E. Bentley argued nearly half a century ago, a performance at the Red Bull.Footnote 60 Depicting no actual event whatsoever – this performance exists only on the page – it is, rather, an amalgamated imagining: a vividly nostalgic celebration of the pre-Civil War stage.

The limited iconography of seventeenth-century printed drama was not intended to recreate a specific performance of the work in question; rather, it served a purpose more emblematic: to remind readers of animated theatrical life, thus widening and deepening the experience of reading plays. Deliberately nonreferential – to put it differently, usefully generic – such frontispieces were sufficiently correct in their broad outlines to conjure up the moment of performance and thereby create a rhetorical space for the reader to inhabit alongside the printed text. Title-page playhouse vignettes demonstrate, though more through abstraction than representation, that stage and page do not exist in parallel universes.

More frequently, and as we have seen with some of Kirkman’s own commentaries, it was the dedications, advertisements, and prefaces that conveyed precise theatre historical information rather than rhetorically invoked performances. Famously, the printer Richard Jones’s address “To the Gentlemen Readers” in his edition of both parts of Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great (Reference Jones and Marlowe1590) contributed to the history of early modern drama in performance by announcing what the text suppressed:

I have (purposely) omitted and left out some fond and frivolous Jestures, digressing (and in my poore opinion) far unmeet for the matter … [that] have bene of some vaine conceited fondlings greatly gaped at, what times they were shewed upon the stage in their graced deformities.Footnote 61

Jones justified his omission of what was “shewed upon the stage” by insisting that Tamburlaine was not drama but proper history; and because it was “so honorable & stately a historie” it ought not to be disgraced by the “fond and frivoulous Jestures” invented by the stage clowns among the Lord Admiral’s Men, no matter how much the audience cheered their antics.

Yet what the text suppressed, the paratext released. However disparaging, Jones’s commentary ensured that the printed work as a whole evoked the performance as a whole, through the ironic elucidation of the very elements that it disavowed. Whether that disavowal was a judicious one for a work that purported to be the “Tragicall Discourses” acted by the Lord Admiral’s Men has ever since been a question to ponder.Footnote 62 But there can be no question that this text wanted to kill the performance in the same way that Marlowe wanted to kill Tamburlaine. Even when, as in this instance, play texts consciously disparage popular performance to appeal to a book-buying elite – an elite presumably loath to set foot in a public theatre – they succeed only too well in making performance manifest, thereby undermining their original polemical intent.Footnote 63

A seemingly contrasting history is recorded in the stationer Walter Burre’s dedication of Beaumont and Fletcher’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle (Reference Burre, Beaumont and Fletcher1613). Writing to “his many waies endeared friend Maister Robert Keysar,” Burre explained that the play – written, so he claimed, in just eight days – failed utterly in performance two years earlier because the audience proved incapable of “understanding the privy mark of Ironie about it.”Footnote 64 At lease in Burre’s account, it was not the play that failed but its uncomprehending spectators. Yet the printed edition kept alive what the theatrical profession might have “smothered in perpetuall oblivion,” hoping that the failed play might again “try [its] fortune in the world” through resurrection in performance. In these various ways, prefaces and dedications in early modern printed drama restored to the body of the text its historicized performative soul.

“To insoul it for the Stage”

I have gone into detail about Restoration playlists partly because they are regrettably unfamiliar to many theatre historians today, although they are well known to literary and book historians. Moreover, I believe that these seventeenth-century documents merit our discipline’s closer attention because they force us to rethink the false binary between dramatic literature and theatrical performance that has more than any other conceptual framework shaped how theatre scholars (and those in adjacent fields) have understood their work and their discipline for over a century. The falseness of that binary is more apparent still when considering, as I have done briefly, the theatrical markers in early modern printed drama. My argument is that this binary – which has more to do with fault lines drawn inside the academy than with the subject matter itself – is actually false to the historical record, the very record whose chronicling and interpretation is the responsibility of theatre scholarship. Beginning in the twentieth century, as I suggested in the Introduction, our discipline allowed itself to misapprehend the very object of its study, largely to craft a professionalizing narrative that – at a particular historical moment and in a particular institutional setting – required theatre to define itself against literature. To put it briefly, the price to be paid for theatre history’s admission into academia was a phony war between text and performance.

Accordingly, we must remain skeptical of overly-determined pronouncements such as Jacky Bratton’s assertion that the heavily used Biographia Dramatica (1782) – and the seventeenth-century playlists upon which it relied – can be dismissed as “tending to privilege the written text.”Footnote 65 A closer look at such early sources, as I have undertaken in this chapter, reveals how misleading that judgment is. One of the first concerns of this book must, therefore, be to dismantle the text–performance binary precisely on historiographical grounds: that is, by scrutinizing the earliest, but now neglected, sources of British theatre history and investigating how they were used. Such scrutiny will lead us to reclaim as theatre historical sources the very documents that have routinely been categorized as purely bibliographic, holding little or no interest to scholars of performance.

That binary did not always exist. Most certainly it did not exist when the documents in question were created, nor for two centuries afterwards. A sale catalogue like Kirkman’s was, literally, just that: a list of items for sale. Produced by the vendor and intended for the purchaser, it became obsolete when the last item was sold. Whatever literary bias resided in Restoration playlists – although bias seems the wrong word – arose from the pragmatics of their initial audience and immediate marketplace purpose. Yet as I have tried to demonstrate, these lists possessed a supplemental historical capability by virtue of their paratexts and, more broadly, by virtue of the knowledge and experience that readers brought to them. Restoration play catalogues ought to be regarded as foundational documents in the history of the British stage: in their conception, in their content, and in their subsequent usage. We can, of course, read them thinly, as mere lists of titles and authors, confusingly arranged and often incorrect. That is more or less how theatre academics have chosen to read them, if they have read them at all.

But we can also, if we choose, read them thickly, as theatrical artifacts. Such a perspective negates neither the commercial value these lists held for their original users nor the bibliographic value they subsequently held for collectors, antiquarians, and, indeed, theatre historians in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Rather, this perspective extends the capabilities of such documents, recovering within them an inherent inclination toward the life in performance of the words on the page. Seventeenth-century play catalogues, far from remaining generically sealed, give rise naturally to a variety of theatrical associations: the custodianship of theatrical memory (“most judiciously discoursed of Poësie”), epitomized in the figure of the talkative and nostalgic William Beeston; judgments about contemporary performance (“the most accomplished Mr. John Dreyden”); and visions of future performances (“to insoul it for the Stage; where it will receive ful perfection”).Footnote 66 For us today, such observations are all in the past tense, including the performances of “ful perfection” that Kirkman imagined, extending to a third generation of Beeston actor-managers. But in their original moment they straddled the past, the present, and the future.

Unsurprisingly, much of this theatrical inflection occurred not in the plays lists proper but in their discursive and allusive paratexts. Much the same was true for the printed drama of the period. In literary theorist Gérard Genette’s influential definition, paratexts function as “thresholds” of interpretation that furnish the reader with a “more pertinent reading” of the work.Footnote 67 Consider this often-cited example of a performative paratext: the epilogue written by Nicholas Rowe and spoken by Mrs. Barry at the Drury Lane benefit for the aging Thomas Betterton in the spring of 1709. Speaking Rowe’s words, the celebrity actress famously invoked Shakespeare’s ghost in a warning to the audience of the frightful consequences were it not to vigorously applaud the performance:

The paratext explains the overall event as amounting to more than the performances of Elizabeth Barry as Cleopatra, Anne Bracegirdle as Octavia, and the ailing impoverished Betterton himself as Antony in Dryden’s All for Love; or, The World Well Lost (1677), adapted from Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. Though the performance of Dryden’s tragedy would certainly have prompted some in the audience to recall the 1704 court production in which the same three performers took the same roles, the epilogue directed the attention of all spectators to wider concerns. It constructed a genealogy of theatrical history in which Shakespeare the patriarch (the ghost of Old Hamlet, the part assigned to him by tradition) returns to bless Betterton, his theatrical son and best interpreter: “Why did I only Write what only he could Play.” In an immediate sense, the epilogue framed Betterton’s long career, then in its final dwindling days; but, ultimately, it placed that career within an even broader frame – the whole history of the stage over the preceding century since the time of Shakespeare himself.Footnote 69 The pastness of the events being conjured up is emphasized by Shakespeare’s transformation into a ghost: the dead, something that can exist only as the past.

In the same way that Rowe’s epilogue offered a more pertinent reading of a Drury Lane performance, Kirkman’s prefaces and advertisements offered more pertinent readings of the (seemingly) bookish information arranged and conveyed in his playlists. Similar strategies were at work in published play texts, the very works summarized in those lists. With respect to both playlists and printed plays, text and paratext form an integrated whole and so must be read together in precisely the same way that a prologue and an epilogue form part of a single interpretable moment along with the performed dramatic work which they both frame and elucidate. Such documents activate a chain of associations in the reader’s mind, the associations informed by a combination of reading, memories of theatregoing, and playhouse lore handed down over the years. Like epilogues and prologues, these texts were living, not static, documents, possessing a performative drive that is easily forgotten – worse, simply unnoticed – when they are read only as catalogue entries.

It is the performance-oriented capabilities of these documents that make them source materials for British theatre history. By taking them seriously as sources for theatre research we find that the history of theatre history will teach us a surprising lesson: The separation between text and performance was not the starting point for our predecessors and thus never the inheritance that we have taken it to be. If we want to understand more fully the origins of British theatre history, that understanding must begin with the realization that its earliest practitioners looked for the affinities between drama and theatre, between page and stage, and not for the antipathies. The antipathies came much, much later.