Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 August 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

Summary

This essay approaches the topic of distortion from an unashamedly recuperative angle. The epigraph here is that most famously reprised biblical quotation: ‘For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known’, from 1 Corinthians 13:12. It is cited out of context in a hundred different songs, television shows, films and poems, including as the title of a 1961 Ingmar Bergman film, which exploits the notion of human misapprehension and the distorted or partial nature of human knowledge, of human works and endeavours in the face of the divine. The perhaps questionable reception of this quotation forms a jumping-off point for our investigation of the reception and/or distortion of medieval texts, from the moment they emerge in written form, to their modern manifestations under foot or digitally translated and transformed.

Within the field of medieval French literature and manuscript studies, the textual and material phenomena of incompleteness, instability and fragmentation – or perhaps what we might rather more positively call continuations, variance and multiplication – have been the subject of a number of studies in recent decades. The discrete text is often left incomplete or unfinished through the common medieval trope of the refusal or deferral of ending or judgement (especially in the dialogued or debate poem), which is projected beyond the diegetic frame of the text through a number of textual devices: an unreliable narrator; an absent judge; a delay to find legal representation; ambiguity, and so on. This might seem unsatisfactory until one realises that a continuation is usually offered, often in the shape of a further text or texts; and indeed that the ‘original’ text gains from its contextual – or as Jean-Claude Mühlethaler puts it, ‘co-textual’ – reading across the linguistic surfaces of a manuscript or printed compilation, or cycle.

In this context, the ‘original’ itself is held up as imperfect, unfinished, continuable; and therefore any ‘distortion’ in the sense of continuation or adaptation may be seen as a positive gain. Indeed, ‘distortion’ itself is a not unproblematic word, since while more often than not used to indicate deviation from a norm or original form in a pejorative sense, it can signify positively in certain contexts.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

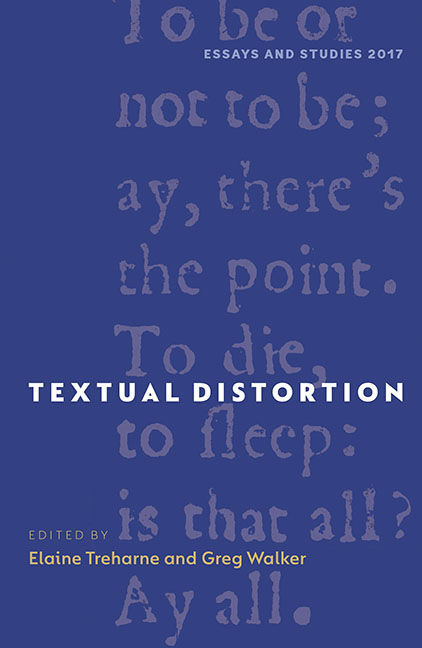

- Textual Distortion , pp. 26 - 46Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017