Resilience through Knowledge Co-Production

Resilience through Knowledge Co-Production Book contents

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-production

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-production

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Co-production between Indigenous Knowledge and Science: Introducing a Decolonized Approach

- Part I From Practice to Principles

- Part II Indigenous Perspectives on Environmental Change

- Part III Global Change and Indigenous Responses

- Epilogue

- Index

- References

1 - Co-production between Indigenous Knowledge and Science: Introducing a Decolonized Approach

from Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 June 2022

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-production

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-production

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Co-production between Indigenous Knowledge and Science: Introducing a Decolonized Approach

- Part I From Practice to Principles

- Part II Indigenous Perspectives on Environmental Change

- Part III Global Change and Indigenous Responses

- Epilogue

- Index

- References

Summary

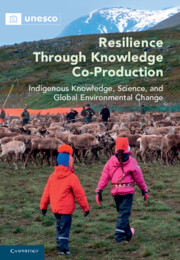

We have entered the era of the Anthropocene. Our rapid transformation of the planet poses a particular threat to socio-ecological systems and the Indigenous peoples who create and sustain them. A strengthened partnership between Indigenous knowledge holders and scientists is required based on decolonized knowledge co-production (DKC). Quite the opposite of scientific extractivism, which selectively exploits local and Indigenous knowledge to its own advantage, and more ambitious than the mere recognition and appraisal of Indigenous knowledge, DKC requires dedicated partners from knowledge systems who have learned through years of collaborative work. This introductory chapter proposes a methodology and ethic for DKC based on a problem-oriented and engaged approach built around mutual trust and benefits, and a profound equity between knowledge systems. It examines the intellectual contributions that laid bare the legacies of colonialism and the hegemony of science, opening the way for DKC: Elinor Ostrom who first coined the term co-production, Bruno Latour and Sheila Jasanoff from science and technology studies, with decisive insights from, among others, Edward Said, Vincent Deloria and Tuhuwai Smith.

Keywords

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Resilience through Knowledge Co-ProductionIndigenous Knowledge, Science, and Global Environmental Change, pp. 3 - 24Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022

References

- 1

- Cited by