Founded in January 1792 by a London shoemaker, Thomas Hardy, and a group of friends, the LCS is commonly seen as the key organisation in the emergence of a new kind of popular radicalism. The 1770s and 1780s had witnessed the appearance of a movement aimed at political education and parliamentary reform, but its participants had been mainly drawn from the landowning classes, associated writers and journalists, lawyers, and other professionals, plenty of nonconformist ministers among them. The LCS came to mediate between these classes and London’s artisans and shopkeepers in the name of ‘the people’ broadly construed. Proposing an unlimited membership and charging a cheap subscription rate of one penny per week, the LCS aimed to broaden the processes of political discussion and the printed circulation of ideas.1 On the national stage, until it was proscribed in 1799, the LCS also played a major part in organising relations between radical societies across England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Modern historians, especially since the revival of scholarly interest in popular conservatism in the 1980s, have been inclined to celebrate the initiative displayed by the LCS, but disparage a perceived lack of cogency in its political platform. H. T. Dickinson, for instance, described the reform movement in general as ‘hopelessly divided on what changes ought to be made’ and unable ‘to devise any effective means of implementing their policies’.2 There is more than a little truth in these judgements, but as bald statements they give little sense of the task facing the reform movement as it sought to animate the constitutive power of the people against the congealed authority of the Crown-in-Parliament.3 The fact of major differences within the reform movement is undeniable, but that is hardly a surprise if we examine any reform or revolutionary movement, successful or otherwise. In the case of the 1790s, this diversity reflects the experimental nature of the movement as it faced a range of new possibilities in the wake of the American and French Revolutions. Almost as soon as a radical reform movement appeared on this new terrain, it also had to contend with all kinds of challenges, not least the government’s attempts to use all the resources of the state to extirpate it.

In the face of these pressures, the LCS and its allies engaged in an attempt to create an expanded public sphere out of the widening of popular debate. In a memorable phrase, E. P. Thompson expressed a wish to rescue those involved from the ‘enormous condescension of posterity’. Nevertheless, even he saw the besetting sin of English Jacobins as ‘self-dramatization’.4 The judgement may be reasonable enough in relation to several of those discussed in these pages, perhaps most obviously John Thelwall, although it may also underestimate the way in which performance, including the performance of personality, was an important aspect of the theatre of Georgian politics across the board. If the LCS and its members critiqued the theatricality of Pitt and others as an empty show, a shabby trick played to deceive the people, they also insisted on their right to produce a drama of their own, with starring roles for radical celebrities. Negative judgements of the radical societies are often predicated on their failure to adhere to a distinct ideological programme, a judgement implying an idea of practice as a mere parole to the langue of intellectual history.5 Sometimes the LCS is represented as disappointingly falling back on conventionally constitutionalist discourse or failing to exploit the political possibilities of the language of natural rights made available by Paine’s Rights of Man. More sensitive to the difficulties of the task it faced would be an acknowledgement of the variety of ways the radical societies put pressure on the authority of constituted power in order to assert the constituent authority of the people. My approach thinks of the LCS in relation to language as embedded in social practices and understands contests over those practices as essential to the politics of the radical movement. The LCS is read not as some absolutely coherent agent, but as a locus for the circulation of print structured by reading, meetings, lectures, conversazione, various encounters in bookshops and many other spaces in the associational world of eighteenth-century London.6

From this perspective, to follow Iain Hampsher-Monk, the politics of the radical societies may not lie simply with the speech act in the text, but in ‘the very act of publication’. In this regard, Hamphser-Monk contends ‘the medium, not the content … is the message, the very fact and facility of such “electric” (a favoured metaphor) communication evinced and comprising the political mobilization of hitherto unpoliticized people from different parts of the country’.7 If this book ends with a defeat of a kind in the passage of the Two Acts through Parliament at the end of 1795, then the triumph of the radicalism of the 1790s was the creation of a popular politics that extended into the nineteenth century. John Bone, Daniel Isaac Eaton, Thomas Hardy, William Hone, Sampson Perry, Francis Place, Thomas Preston, and John Thelwall are only a few of those appearing in these pages, who re-emerged as writers, publishers, booksellers, and activists in the radical cause after 1800. Nineteenth-century commemorations of the Scottish martyrs and those acquitted of treason at the end of 1794, now largely forgotten in British public culture, were only the outward sign of a continuity of popular radicalism that extended into the reform agitation of the 1820s and 1830s and beyond.8

Some of the activities of the radical societies have been regarded as an attempt to discipline a plebeian culture of ‘riot, revelry, and rough music’ into the practices of political citizenship, but there are ample reasons to be wary of assuming that forms of organisation, lectures, and debating societies, for instance, were experienced as a new form of discipline, when they were variations on what were becoming familiar features of the commercial culture of ‘the town’, increasingly accessible to the social classes who participated in the LCS.9 The various sociable gatherings Francis Place later described as mere epiphenomena of the serious political business of the LCS were events taking place in a complicated urban terrain where customary practices had been adapting for some time to interlinked worlds of print and leisure. In this regard at least, the LCS was an extension of the phenomenon – identified by John Brewer with the Wilkes agitation in the 1760s – of ‘independent men, made free through association and educated through the rules, ritual and constitutions of their own clubs and societies’. These associations partly legitimated their activities through the ‘invented’ tradition of popular resistance that they claimed had produced the Revolution of 1688.10 The popular societies laid claim to this tradition – with various redefinitions of ‘independence’ – and extended it further towards a democratic idea of the sovereignty of the people, sometimes styled ‘the general will’, as the constituent power. Towards the end of Rights of Man, Paine had contrasted the ‘savage custom’ that solved disputes over government by civil war, with ‘the new system’ where ‘discussion and the general will, arbitrates the question’ and ‘reference is had to national conventions’.11 At its most radical, this ‘new system’ extended to arguing for the right to call a convention to collect the general will, and even, so the government maintained, to represent it. Over 1793–4, as John Barrell has shown, Pitt’s ministry began to construe these arguments not only as seditious but also treasonable in so far as they presented the popular societies as more legitimately representing the people than Parliament. For their part, members of the LCS like John Baxter, as we shall see in Chapter 2, insisted that attempts to stop the popular societies consulting together were a sign of tyranny that triggered a customary and constitutional right of resistance.

There were certainly tensions within the LCS about discipline and organisation, anxieties about presenting a respectable face to the public, but also arguments about what constituted proper forms of public practice in the name of political citizenship. Eley may be right to note that ‘the advanced democracy of the LCS presumed the very maturity and sophistication it was meant to create’. Polemically, the presumption was essential to the case for universal suffrage, but the struggle to create a democratic culture in the popular societies was a sustained and extraordinarily rich response that seriously alarmed the government of the day and prompted it to take measures.12 Many contemporaries – not only radicals – regarded these measures as both unnecessary and unprecedented. The response to them formed a crucial part of the shaping context of radical print culture. Charles James Fox described Pitt’s measures culminating in the Two Acts as a ‘Reign of Terror’.13 If the phrase is characteristically melodramatic, it does at least speak to the emergent sense of a new landscape for political discourse, one radicals like Baxter regarded as a state of exception that might justify calling a convention.14 In the 1770s, John Jebb, a favourite author of Hardy’s, had insisted on ‘the acknowledged right of the people to new-model the Constitution, and to punish with exemplary rigour every person, with whom they have entrusted power, provided in their opinion, he shall be found to have betrayed that trust’.15 Pitt’s attempts to close down the avenues open to political opinion suggested to some members of the LCS that the moment had arrived when the compact between the people and the state had to be renegotiated. Censorship and repression, in this regard, could both generate and thwart radicalism.

The LCS was part of a complex and distinctive print culture, not without its internal stresses, far from it, but one that was shaped by the practices of eighteenth-century society more generally and the developing contexts of which it was a part. At its heart is the relationship between the LCS and the SCI, founded in 1780, but revived in the early 1790s under the gentleman radical John Horne Tooke, to disseminate political information. The most obvious fruit of the collaboration between the LCS and the SCI was the circulation of cheap editions of Paine’s Rights of Man, but their relationship continued in one form or another, and with different degrees of intensity, from 1792 until the treason trials at the end of 1794. There were important tensions between the two societies, not least to do with social status, roughly speaking between the politer constituency of the SCI and the more popular complexion of the LCS, but these differences were far from absolute. Some key individuals, for instance, Joseph Gerrald, were members of both societies, refusing to observe distinctions between the elite and the lower classes that structured received ideas of who exactly constituted the political nation. Figures like Gerrald and his associates Charles Pigott and Robert Merry, both of whom are discussed more closely in Part II, were regarded as shocking examples to the landowning classes of the personal consequences of dabbling in political alliances with the lower orders.

Part II of this book attends more closely to individuals and texts involved in this broader picture and the complications of their careers. The relation of the conduct of individuals to the societies of which they were members was a crucial one, not least when it came to prosecutions for political opinion. Was a libellous publication the responsibility solely of its author or publisher, or did it represent the official point of view of the LCS or the SCI? This question was asked at more than one trial and also in Parliament. The world of print explored here is not just constituted out of the publications of the SCI and LCS, or of the other political societies associated with them, but also out of the ‘unofficial’ publications of individual members. Some of those involved in the societies, including, for instance, Merry and Pigott, assumed a right as gentlemen to comment on public affairs in print. They were already authors before 1792, practised at writing for newspapers and pamphlets, and, in Merry’s case, associated with Sheridan’s management of the press. Their situation was rather different from that of most members of the LCS, but these did include many who were already immersed in print culture as booksellers, avid readers, members of book clubs and Bible societies, like Thomas Hardy and his brother-in-law George Walne. Such men probably understood their involvement in the LCS as part of a more general commitment to moral improvement. John Thelwall certainly harboured and achieved literary ambitions before he became involved in radical politics. Others, like the silversmith John Baxter, became authors and publishers through their participation in radicalism, becoming ‘literary men’, to use a term that crops up more than once in the archive. Frequently the LCS showed respect for and even deference to the professional skills of writers, not least in late 1794 when it needed copy for The Politician. At the end of his trial for treason in 1794, the judge, Chief Justice Eyre, confessed to finding Thelwall’s ‘character’ to be ‘one of those extraordinary things that puzzle the mind the more they were examined’. How could ‘a man of letters, associating with the company of gentlemen’ have conspired with and even encouraged those accused of plotting treason?16 The judge’s question was a specific version of a more general puzzle. The question of how a distinctive republic of letters could have emerged from such places remained an enigma to a ruling elite, rarely willing to grant someone like Thelwall the literary status begrudgingly allowed to him by the Chief Justice.

Radical print culture in the 1790s was structured as much by tensions between its members as their cooperative will to change their world for the better. The disorientating speed of events that the French Revolution unleashed across Europe further complicated things, as participants had to decide upon the significance of those events for their sense of what was possible in the British situation. As France moved from ancien régime to constitutional monarchy and then to a republic, so the possibilities of what might be done by reform changed too, a fact reflected even in Thomas Paine’s writing. Often described as a republican because of his role in the American struggle against Great Britain, Paine shifted his thinking about Europe as different possibilities emerged in Britain and France. He moved from supporting a constitutional monarchy under Louis XVI to a republic, at least by late 1791, but only announced his support for universal suffrage in Britain in his Letter Addressed to the Addressers, published in August 1792. Quite probably, this development was influenced by his experiences with the LCS and SCI over the spring and summer of 1792.17

When we examine the archive of the radical movement in London, a picture emerges of less-heralded individual members of the LCS and SCI also revising their sense of the possibilities before them, even if the official line of the societies stuck to the Duke of Richmond’s plan of universal suffrage and annual parliaments as their immediate objective. John Horne Tooke famously described his attitude to reform in terms of getting off the Windsor coach at Hounslow, even if his fellow passengers intended to proceed to the terminus. The LCS encouraged all the societies to get on the stage to Richmond and debate the final destination once on board. The radical societies did not simply act out an inherited script of parliamentary reform. They continually recycled resources from the past, often quite literally by republishing the duke’s plan from the 1780s, or even earlier texts from the commonwealth canon. The cutting and pasting techniques that were essential to the rapid-fire achievement of periodicals like Thomas Spence’s Pig’s Meat (1793–5) or Eaton’s Politics for the People (1793–5) did not simply endorse the texts they reproduced, but implicitly transformed them in the interests of raising the political consciousness of their readers. Both Eaton and Spence were LCS members who suffered imprisonment for their commitment to the cause, but by no means all their publications were official LCS materials.18 They published ideas that went beyond those endorsed by the LCS as a corporate body, as with Spence’s appropriation of James Harrington’s Oceania (1656) in support of his radical land plan.19 Nevertheless, anxious as the LCS and SCI may sometimes have been to distance themselves from the views of individual members, Spence included, they were committed to putting a diversity of texts into circulation to stimulate widespread discussion of possible political futures. The Politician described the aim of the LCS as ‘the diffusion of political knowledge by a system of mutual instruction’, an ambition interrupted by ‘that system of unconstitutional persecution, which was the harbinger of the present most execrable and ruinous war’.20 Even so, the journal declared itself open to contrary points of view, including those of a veteran reformer, ironically naming himself ‘An Aristocrat’, who contributed an essay to the first issue arguing against the policy of universal suffrage that the LCS officially supported.

Publicity

Making the question of publicity central to the radical societies in the 1790s may smack of anachronism, but it was a conscious part of their thinking and shaped their political practice. Perhaps nothing puts this into starker perspective than the reasons Maurice Margarot gave in 1796 for refusing the chance to escape from Botany Bay on the American ship that spirited his fellow convict Thomas Muir away:

I came in the Public cause, and here I will wait for my recall by that Public, when the cause shall have prospered as perhaps it will have done before you receive this.21

Transported for his participation in the British Convention at Edinburgh of late 1793, Margarot always defined himself as someone acting in a ‘Public cause’. To creep away on an American ship, as he saw it, would have been to betray the public function that the LCS placed at the centre of its mission. Looking back from 1799, Hardy claimed that ‘the Society was very open in all its measures, indeed their object was publicity, the more public the better’.22 Publicity was not simply the medium for the message of parliamentary reform; it was part of its object.

The LCS conducted itself in the manner in which it understood public bodies to behave. In the process, it affirmed the right of its members – whatever their social class – to be regarded as an actively constituent power, part of the political nation. In this regard, as John Barrell memorably puts it, the LCS also offered its members not just ‘jam tomorrow’, but also ‘a sense of immediate, present participation, to whoever would join it and engage in [their] activities and debates’. Barrell is surely right to claim that ‘for many members of the LCS the prospect of participating in the society’s democratic structures may have been as powerful in persuading them to join as the prospect of eventual parliamentary reform’.23 Ironing over some of the internal controversies about the LCS’s constitution, a matter I will return to at the end of the next chapter, Francis Place, writing much later, gave a succinct account of the organisation of the LCS:

The Society assembled in divisions in various parts of the Metropolis, that to which I belonged was held; as all the others were weekly; at a private house in New Street Covent Garden. Each division elected a delegate and sub delegate, these formed a general committee which also met once a week, in this committee the sub delegate had a seat but could neither speak nor vote whilst the delegate was present.

He also gave a glimpse into the relationship between the official business of the LCS and the penumbra of print sociability that went on around it:

We had book subscriptions … the books for which any one subscribed were read by all the members in rotation who chose to read them before they were finally consigned to the subscriber. We had Sunday evening parties at the residences of those who could accommodate a number of persons. At these meetings we had readings, conversations and discussions. There was at this time a great many such parties, they were highly useful and agreeable.24

Place’s account is more or less corroborated from other sources, including spy reports, which speak of the admixture of official meetings, still often centred on reading, and more informal conversaziones or ‘parties’. Both the divisional meetings and these parties could be much more convivial than Place makes them sound, but it would be wrong to assume that only the more raucous sorts of sociability were somehow authentically ‘popular’. For one thing, toasts and songs, often with copious consumption of alcohol, were ubiquitous across all classes of the associational world. John Horne Tooke, the gentleman radical of the SCI, often got spectacularly drunk at political dinners, as several visitors noted, including those Whigs who regretted attending the infamous anniversary dinner of the SCI on 2 May 1794. The consequences of such conviviality could be grave. On 24 January 1798, at a meeting to celebrate Fox’s birthday at the Crown and Anchor, attended both by Whig politicians and members of the LCS, the Duke of Norfolk toasted ‘our Sovereign’s health … the Majesty of the People!’ The toast was seen as a deliberate slight to the king and provoked considerable commentary.25 The king saw to it that the duke was dismissed from his positions as colonel of the militia and Lord Lieutenant of Yorkshire.

Many of the activities encouraged by the LCS represent what Lottes has called a ‘train[ing] in the democracy of the word’.26 Place’s description of a divisional meeting certainly seems to sanction this vocabulary:

The chairman (each man was chairman in rotation,) read from some book or part of a chapter, which as many as could read the chapter at their homes the book passing from one to the other had done and at the next meeting a portion of the chapter was again read and the persons present were invited to make remarks thereon. As many as chose did so, but without rising. Then another portion was read and a second invitation was given – then the remainder was read and a third invitation was given when they who had not before spoken were expected to say something. Then there was a general discussion. No one was permitted to speak more than once during the reading. The same rule was observed in the general discussion, no one could speak a second time until every one who chose had spoken once, then any one might speak again, and so on till the subject was exhausted – these were very important meetings, and the best results to the parties followed.27

These details and other aspects of LCS governance correspond closely to the activities of book clubs and reading societies widespread in the associational world of the eighteenth century, not least in the attempt to create a level plane of discourse to facilitate equitable participation in discussion. Lottes claims that the primary aim of the LCS became a disciplinary concern for each of its members ‘to acquire knowledge on his own without intellectual guidance’. The Report of the Committee of the constitution, of the London Corresponding Society (1794) insisted that the primary duty of a member was ‘to habituate himself both in and out of his Society, to an orderly and amicable manner of reasoning’. Many members were committed to the idea of ‘rational debate’. Sometimes this insistence sounds like a reactive proof of their abilities against the insinuations of much conservative propaganda to the contrary, but even ‘rational debate’ could imply a variety of practices. The report of the committee of constitution was soon mired in arguments about the best form of democratic protocol within the LCS itself, especially the relation of the divisions to the central committee. In the context of these arguments about the report of the committee on the constitution, Hodgson and Thelwall clashed violently about systems of governance early in 1794: ‘Hodgson argued in favour of some System being requisite Thelwall against the necessity of any and his opinion was most applauded.’28

This account might be tainted by the exaggeration of a spy report eager to identify the LCS with anarchy, but other sources confirm that such differences did cause schism within the LCS in 1795. Discussed at more length in Chapter 2, these disagreements were not simply matters of form in any superficial sense. They were rather part of serious debates about how to mediate the sovereign will of the people. These debates could focus on different aspects of the various media of expression available to the society, taking in questions of how members ought to address each other or the conduct of large political meetings. In his account of these debates, Lottes may be relying too much on Place’s perspective when he assumes that ‘the divisions were turned into political classrooms from which all plebeian sociability was banned’.29 I will return to the convivial sociability of songs and toasts later in this chapter, but a major part of the plebeian life world that Lottes ignores is religion. John Bone and Richard Citizen Lee, among others, refused to leave their beliefs at the door of the meeting, even if Thomas Hardy did, despite the strength of his religious convictions. Some LCS divisions defended their right to create their own political space against the centralising drive identified by Lottes. The very idea of the division as a reading group could play into the resistance to political organisation. Furthermore, what was read at the meetings seems to have extended from classics of political philosophy to the squibs and broadsides that could make these gatherings more free and easy than classrooms.30 From this perspective, again, the Lottes version of political education at the LCS appears too austere. Toasts and songs, squibs and burlesques, were all part and parcel of the theatre of Georgian politics broadly construed, familiar to patrician and plebeian alike. Reading often coexisted with singing. Political education was not confined, in this sense at least, to the kinds of texts that might produce the disciplined citizen of Lottes’s account.

These different currents flowing into the LCS meant there were necessarily tensions about the kinds of activities and publications to which the society should lend its name. Clubbing together over books – reading, buying, and printing them – had an obvious economic advantage that John Bone made clear when he proposed a publishing scheme to the LCS in May 1795. He had just seceded in a dispute over constitutional arrangements, probably exacerbated by his religious beliefs, to set up the London Reforming Society, but the schism did not prevent him proposing cooperation for the dissemination of political information. ‘Among the embarrassments the Press has laboured under’, wrote Bone back to his old allies in the LCS, ‘none has had a greater tendency to impede the progress of knowledge, than the difficulty of circulating books.’ Bone proposed that the LCS join together with the Reforming Society to print political books in large runs, copies being given to members in return for their membership dues; ‘by this means, an uniformity of sentiment would be produced in the whole Nation, in proportion to the diffusion of knowledge’. Print magic, here, it seems, brings with it the idea of an ultimate union as the terminus of discussion and debate. More prosaically, the economic advantages of Bone’s plan would also be ‘a very powerful stimulus to induce men to associate’.31 He also addressed a perceived want of matter brought up in the reply to his original proposal. First, he answered, ‘there are in the Patriotic Societies splendid talents, that only want the calling forth into use’. Secondly, ‘why not publish the works of other authors … publishing anything that is calculated to do good’. He mentions Joseph Gerrald’s A Convention the Only Means of Saving us from Ruin (1793), Redhead Yorke’s Thoughts on Civil Government (1794), and ‘any other useful book, of which you can get the copy-right’. Finally, he suggests, ‘there is no necessity to confine ourselves to Politics’; perhaps hinting at his religious interests, ‘there is not a species of knowledge from which some good might not be extracted’.32 The LCS replied positively. Members from the two societies met to discuss the plan, but the collaboration never seems to have got beyond an abridged version of the State of the Representation of England and Wales, already published by the societies in 1793.33

Choosing which other texts should be put out in the name of the societies would almost certainly have led to wrangling, especially in the light of their recent constitutional schism and Bone’s religious opinions. Before he seceded, Bone objected to works like d’Holbach’s The System of Nature and Paine’s The Age of Reason being circulated around the divisions.34 Questions over exactly which texts the LCS should issue in its name caused problems from early on in its history. These problems were exacerbated once it became clear that government surveillance would be quick to identify the LCS with any views that could be construed as seditious. The LCS printed material primarily to encourage public discussion, but also to assert – even to memorialise – its right and the right of the people at large to a place in national debate: addresses to the public, to the king, and accounts of its own constitution and resolutions were the staple of its official output. In 1795 the London Reforming Society adopted the same method: ‘Publicity of conduct, discovers purity of motive; it was therefore being just to yourselves when you resolved to publish your proceedings.’35

On 11 July 1793, the central committee of the LCS met to discuss events at its general meeting, held three days before, where an address to the nation had been read. Written by Margarot, the address was chosen from three originally submitted to the committee.36 As was so often the case with the LCS, the July meeting was taken up with matters of publicity and its costs. An error in the printed version of the address was discussed and accounting for ticket receipts took up most of the rest of the meeting. Finally, coming to ‘other business’, George Walne reported that he had found a pile of pamphlets intended for use as wrapping paper on a counter at a local cheesemonger’s. The pamphlet was The Englishman’s Right: A Dialogue (1793). Walne purchased the whole bundle and offered it to the central committee at cost price (3 farthings each copy). Written by Sir John Hawles and originally published in 1680, Walne had come across the eighth edition of 1771. After some discussion, the LCS central committee accepted Walne’s terms, but then entered into several weeks of deliberation over what to do next. At the general committee two weeks later, one delegate brought forward a motion to print a new edition. Eventually, a sub-committee did some light editing, translated all the Latin phrases into English, and added an appendix on the empanelling of juries, a topic of pressing concern for their members facing prosecution; but this summary hardly does justice to the fate of the pamphlet over the next few months.

First, a committee meeting postponed publication until it could be discovered how many copies each division would buy. A meeting on the first day of August reported back that the divisions (somewhat optimistically) had promised to buy 750 copies. The committee decided to charge members 2d, strangers 3d, with 4d marked ‘on the book’. Two thousand were to be printed ‘& the press kept standing’. The country societies were to be informed of it by circular letter. The printer’s estimate had said it would not cost more than 2d per copy to reprint with the appendix. These decisions produced only another round of deliberation. The appendix on juries now had to be written. A sub-committee was appointed to write it consisting of Joseph Field, Matthew Moore, Richard Hodgson, John Smith, and George Walne. A week later the central committee met to discuss their work. It approved the edition, but censured the sub-committee for having already submitted it to the press. The print order was stopped. The next meeting delayed it again, although the secretary was given an order to purchase copies of Richard Dinmore Jr’s A Brief account of the Moral and Political Acts of the Kings and Queens of England for distribution around the society.37

Discussion of the appendix was still going on in September when a mistake on a technical question was discovered. John Martin was called in to give his expert legal opinion.38 Only on 19 September did the LCS finally order The Englishman’s Right to be printed. Hardy wrote to various other societies encouraging them to take copies. On 17 October, he asked Henry Buckle of Norwich to promote the pamphlet as ‘a book that ought to be in the possession of every man’. Eight days later, he wrote to Daniel Adams, secretary to the SCI, offering the pamphlet on the same terms, before proceeding to news of the election of delegates to the Edinburgh Convention.39 More than the 700 projected were sold, but the receipts were much less than must have been expected if the LCS was calculating a return of 2d a copy or more. Although some of those sold probably ended up as cheese wrapping anyway, at least one survived to be passed on to another generation of radicals. When Hardy wrote to the Mitcham Book Society in August 1806 to donate various pamphlets to them in hopes of keeping the flame of reform alive, The Englishman’s Right was among them.

This extended account of The Englishman’s Right serves to illustrate how long and hard the LCS debated what to put out in its name. Beyond its list of official publications, individual members produced a wealth of printed matter in their own names or anonymously; material read, discussed, sung, or otherwise performed at meetings. The question of the extent to which this material was owned by the radical societies was a fraught one, inevitably when the government was aiming to fix responsibility for seditious libel and later treason. After being arrested in May 1794, Hardy was interviewed by the Privy Council. The council asked about Eaton’s role as a printer. Hardy acknowledged the bookseller’s association with the LCS, but also took the view that Eaton ‘prints freely – too freely’.40 The response is not only, I think, a self-protective reflex at a juncture when the judicial process was putting Hardy’s life in hazard, but also indicates some of the tensions within the embryonic democratic culture being fostered by the LCS. Why would Hardy worry about Eaton’s freedom? Hardy himself was no narrow reformer focused solely on parliamentary reform. Although he came to the idea of the LCS through reading SCI publications from the 1780s, he also had a background in religious dissent, possibly also in the Protestant Association, but definitely with the campaigns for the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts and for the abolition of the slave trade.41 All these contexts would have given him ideas about ‘publicity’ and the way it worked, not least in relation to the politics of petitioning.42 Hardy always showed himself anxious about the public face of the LCS, but there was a more general concern to find appropriate forms of intervention. The LCS was confident about the transformative power of print, but also careful about its forms and protocols.

Before turning to discuss some of the general attitudes to print in the radical societies, there is more to be said about the LCS in relation to Jürgen Habermas’s idea of the public sphere.43 Among others critical of Habermas’s idealisation of the ‘bourgeois public sphere’, Eley has insisted on the ‘diversity’ of the eighteenth-century public sphere, which he defines as always ‘constituted by conflict’.44 Explicitly thinking about groups like the LCS, Eley claims that the French Revolution encouraged various subaltern groups to claim for themselves the emancipatory language of the bourgeois public sphere: ‘It’s open to question’ he continues, ‘how far these were simply derivative of the liberal model (as Habermas argues) and how far they possessed their own dynamics of emergence and peculiar forms of internal life.’ Among these alternative dynamics, Eley acknowledges the variety of religious traditions that certainly informed the development of men like John Bone, Thomas Hardy, Richard Lee, and George Walne. These and other aspects of urban culture helped to sustain an alternative to Habermas’s bourgeois public sphere, says Eley, that was ‘combative and highly literate’.45 Anticipating aspects of Eley’s critique, Terry Eagleton claimed that the 1790s witnessed the emergence of what he called a ‘counter-public sphere’: ‘a whole oppositional network of journals, clubs, pamphlets, debates and institutions invades the dominant consensus, threatening to fragment it from within’.46 Key words here relative to the question of dependency raised by Eley are ‘invades’ and ‘within’. There is no doubt that the activities of the LCS and its members disclosed the limits of the inclusive idea of the public that Habermas writes about. Pitt’s repression from 1792 showed that those outside the political classes possessed no acknowledged right to free debate, at least not when it came to questions of political representation and reform. Out of this situation, the popular societies managed to create the vibrant print culture that is the focus of this book, but the achievement was not predicated on any autonomously plebeian public sphere. Rather the LCS developed various forms available in the ‘urban contact zone’ where, however unevenly, ‘elite’ and ‘popular’ cultures interacted, in terms, that is, of its deployment of already existing platforms such as debating societies, reading groups, the newspapers, and other aspects of print sociability that had developed from at least the time of the Wilkes agitation.47

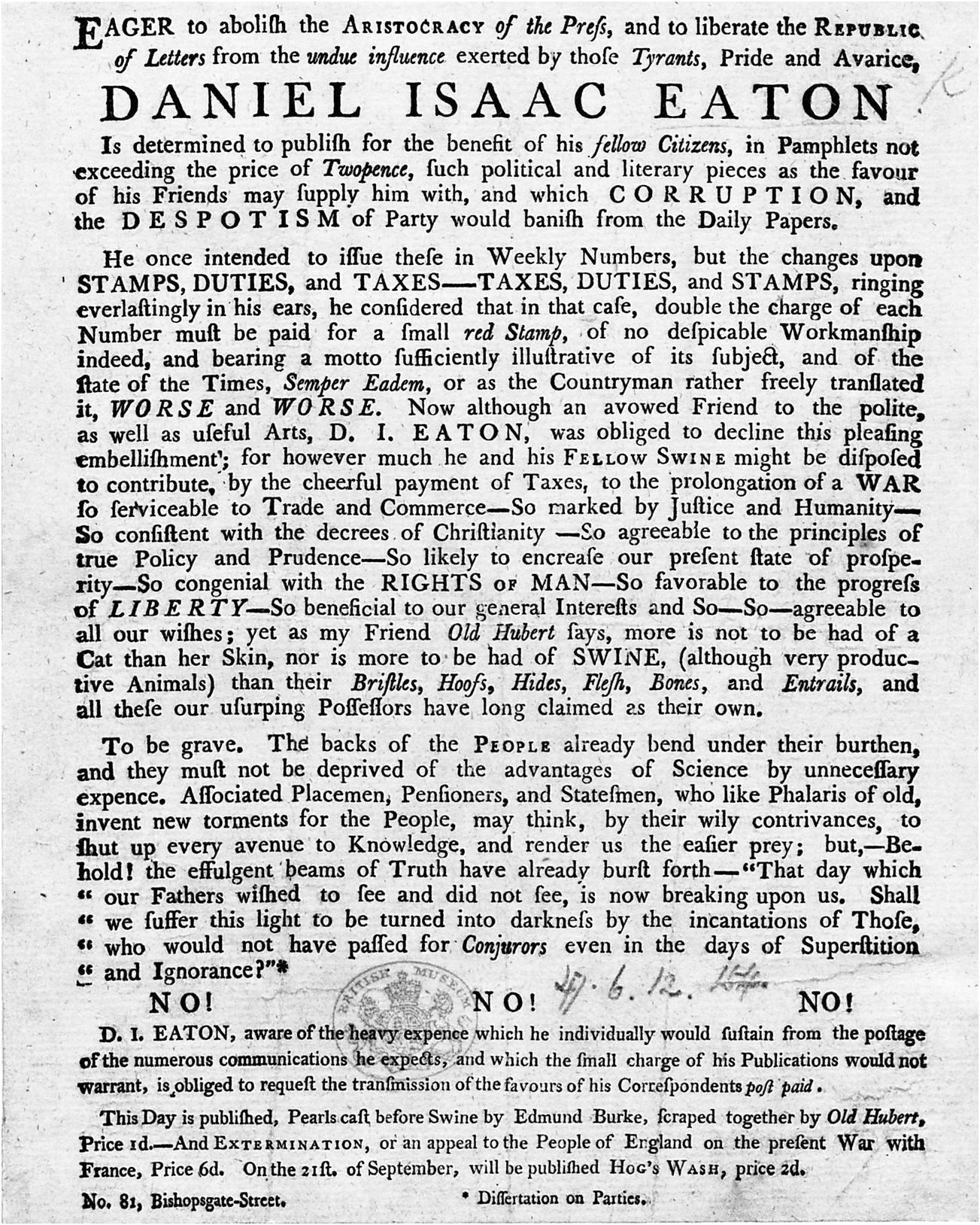

In 1793, having faced a second unsuccessful prosecution for selling Paine’s writings, Eaton issued a handbill announcing his disgust at the ‘aristocracy of the press’ and his determination ‘to liberate the republic of Letters from the undue influence exerted by those Tyrants, Pride and Avarice’ (Figure. 2). For some of Eaton’s readers, especially any with a complacent faith in print magic, the phrase ‘aristocracy of the press’ may have been an oxymoron. The press was widely thought to operate with an inherent tendency to undermine aristocracy and open oligarchy up to public scrutiny. Others, on the other hand, already had bitter experience of the point he was making. Eaton was showing up the contradiction between the emancipatory claims of the republic of letters and the practical barriers to participation. For Eaton, the ‘republic of Letters’ was not a space where freedom of exchange was guaranteed, but a place in need of liberation. Eaton’s response to the situation was to start publishing ‘for the benefit of his fellow Citizens, in Pamphlets not exceeding the price of Twopence’. At the foot of his handbill, Eaton advertised the first fruits of this new policy: ‘Pearls Cast before Swine by Edmund Burke, scraped together by Old Hubert’, that is, by the apothecary James Parkinson; ‘extermination, or an appeal to the People of England on the present War with France, for 6d’, and finally, on 21 September, the first part of the periodical Hog’s Wash, later known as Politics for the People.48 The Extermination pamphlet might be called Eaton’s first original publication, allowing that it was a typical miscellany that looked towards the more daring mixture of his Politics for the People. There Eaton cooked up a rich stew into which were thrown contemporary newspaper squibs, songs, and excerpts from the Whig canon. From August 1794, Eaton also produced a series of Political Classics, including authors such as Thomas More, Algernon Sydney, and, as we have seen, Rousseau. This series has been seen as proof of Eaton’s affiliation to a ‘Real Whig’ tradition, but did these texts somehow retain a stable meaning across multiple platforms?49 The inclusion of Rousseau suggests that something spicier was going on. Certainly Eaton seems to have believed there was an English tradition of liberty worth knowing, but continually reverenced only in the breach by the nation’s elite. To use the title of a miscellany published by the Aldgate Society of the Friends of the People earlier in 1793, it was ‘a thing of shreds and patches’, but one that might be reworked and put to good use by new readers.50 Eaton did not imagine any autonomous tradition of plebeian opposition, but tasked his readers with newly determining the shape of the public sphere.

Fig 2 Daniel Isaac Eaton [A circular, together with a prospectas of a series of political pamphlets.]

Print magic

Michael Warner begins his study of the role of print culture in the American Revolution with the discussion of an essay by John Adams. Writing in 1765, Adams narrated the progress of print as ‘a relation to power’ a narrative of an idea of the press as ‘indispensible to political life’. Carefully distancing himself from its causative claims, Warner sees this narrative as emerging fully in the Atlantic world of the mid-eighteenth century.51 This faith was a pervasive part of eighteenth-century discourse, especially in the Anglo-American Protestant imagination, where it functioned in opposition to an idea of feudal and papal tyranny. From perspectives Adams shared with many others in the anglophone world, print had freed the people from a ‘religious horror of letters and knowledge’.52 Print is not simply the medium for new ideas in this kind of narrative, but comes bearing a truth in itself; ‘letters have become a technology of publicity whose meaning in the last analysis is civic and emancipatory’.53 Sharing Warner’s scepticism as to the truth of its claims, I understand this narrative – for all its self-identification with Enlightenment – as a faith in print’s magic. Traces of it appear in Paine’s confidence that ‘such is the irresistible nature of truth, that all it asks, and all it wants, is the liberty of appearing. The sun needs no inscription to distinguish him from darkness.’54 The spread of truth, paradoxically needing ‘no inscription’, transcends the need for any mediation whatsoever. This magically transformative power stands in a certain tension with the more calibrated emphasis elsewhere in Rights of Man on continual debate and discussion.

Recent historians of print have tended to echo Warner’s scepticism about taking such attitudes as evidence of the causative power they celebrate. Leah Price, for instance, distances herself from ‘the heroic myth – whether Protestant, liberal, New Critical, or New Historicist – that makes textuality the source of interiority, authenticity, and selfhood’.55 Price is developing James Raven’s caution about placing too much trust in eighteenth-century accounts of print and progress, including those that link ‘the activity of the press to increased literacy and popular political energies’.56 Those within the radical movement in the 1790s repeatedly made this link. Place’s retrospective accounts of the LCS as a moral force, for instance, depended on its introduction of its members to the virtues of print: ‘It induced men to read books, instead of wasting their time in public houses, it taught them to respect themselves, and to desire to educate their children.’57 Jonathan Rose claims that men like Place and Hardy ‘were acutely conscious of the power of print, because they saw it work’.58 But Raven’s caution against extrapolating from individual cases to the larger picture is worth heeding: ‘The testimony of the self-improved endorses an undue reverence for the process and volume of learning.’59 Encounters with print often did have a transformative effect, but it was not always so, and print was not necessarily as magically effective as some accounts represented it. The LCS spent a lot of time working hard to create and calibrate its effects.

Looking back on his experiences in the 1790s, Thomas Preston, who had been a member of the LCS, represented reading as crucial to the political awakening of the people:

The increase in reading had dissipated the delusion, and people now knew the meaning of words, whether spoken in the Senate, written in lawyer’s bills of costs, or printed on an impress warrant. The charm of ignorance which had so long lulled my mind into comparative indifference at people’s wrongs, was now beginning to disappear. The moral and political sun of truth had now arisen. The arguments, the irresistible arguments, laid down by the ‘Corresponding Society’ had riveted my heart to the cause of liberty.60

Popular radicalism often exploited the idea of the improving power of reading for rhetorical purposes, for instance, against the counter-revolutionary narrative that Paine and his associates were spreading poison through the press. What was poisonous from the loyalist perspective was a panacea against ignorance for radicals. Many of these thought that it had been working its curative effects ever since the invention of the press.

The idea of the emancipatory magic of the printing press appears again and again as a trope in the 1790s. In 1792, for instance, David Steuart Erskine, Earl of Buchan, and elder brother of Thomas Erskine, the chief defence lawyer at Paine’s trial, argued that if a free constitution was ‘the panacea of moral diseases’, then ‘the printing press has been the dispensary, and half the world have become the voluntary patients of this healing remedy’.61 Two years later, in a speech given at the grand celebration of the acquittal of Hardy, Horne Tooke, and Thelwall, the Earl of Stanhope transposed Buchan’s medical trope into a more familiar image of enlightenment:

The invaluable art of printing has dispelled that former Darkness; and like a new Luminary enlightens the whole Horizon. The gloomy Night of Ignorance is past. The pure unsullied Light of Reason is now much diffused, that it is no longer in the power of Tyranny to destroy it. And I believe, and hope, that glorious intellectual Light will, shortly, shine forth on Europe, with meridian Splendor.

Neither Buchan nor Stanhope, as it happens, subscribed to the strongest version of print magic in these speeches. Their faith was anchored in a constitutionalist perspective wherein the press mediated prior forms of legal and political authority. Stanhope qualified his paean to the press:

The Art of Printing (that most useful and unparalleled Invention) is however, as nothing, without that, which alone can give it energy and effect: you need not to be told, that I mean, the sacred liberty of the press, that Palladium of the people’s Rights.62

Stanhope made his own contribution to the art of printing, designing the first iron letterpress in 1800, a development that allowed a greater number of impressions per hour, and speeded up the administration of the panacea of print to the patient. In this case, Stanhope’s version of print magic drove technological innovation, not the other way round, but it also drew back from those versions of Paine’s faith in the irresistible power of truth that perceived no limits to its horizons.63

Where radicalism dreamed of print as ‘a medium itself unmediated’, then it often used the trope of an electric immediacy of communication.64 Thelwall, as Mary Fairclough has noted, routinely spoke of ‘a glowing energy that may rouse into action every nerve and faculty of the mind, and fly from breast to breast like that electrical principle which is perhaps the true soul of the physical universe’.65 His was the positive version of the ‘electrick communication every where’ feared by Edmund Burke, promising or threatening, depending on one’s point of view, to jump across all channels of ‘transmission’.66 Elite reformers like Buchan and Stanhope may have had reservations about the democratic implications of this trope. In contrast, Thelwall’s political lectures, perhaps the key radical medium of 1794–5, speedily reissued in pamphlet form and widely advertised and reported in the press, often echoed Paine’s sense of the potentially limitless effects of the power of truth.67 In a lecture on the history of prosecutions for political opinion, he projected the idea of an ineluctable progress flowing from the invention of printing. He quoted John Gurney, defence lawyer at Eaton’s second trial, discussed below, on the idea that the libel laws had originated in a panicked response to the emergence of the printing press:

when the invention of printing had introduced political discussion, and when seditious publications (that is to say publications exposing the corruptions and abuses of government and the profligacy of ministers) made their appearance … The control of the press was placed in admirable hands, a licenser, the king’s Attorney General, and a court of inquisition, called the Star Chamber.

Interestingly, Gurney was representing the art of printing as the antecedent of political discussion. Not simply a medium that reports debate, the press is imagined as its condition of possibility. Typically, Thelwall swelled to the theme in the lecture room:

Fortunately for mankind the press cannot be silenced. Placemen and pensioners may associate for ever; inquisitions may be established, and the Nilus of corruption pour forth its broods of spies and informers; but wherever the press has once been established on a broad foundation, liberty must ultimately triumph. It is easier to sweep the whole human race from the surface of the earth than to stop the torrent of information and political improvement, when the art of printing has attained its present height.

For Thelwall, so many of these ‘engines of truth’ were now dispersed around the globe that the progress of liberty was unstoppable. Radical print culture, as John Thelwall told it, was the articulation of a spirit of progress hard-wired into the story of the press.68

From this perspective, whatever local setbacks might occur, an inherent logic guaranteed the irreversible spread of knowledge and thence emancipation. There was often a strong polemical motive recommending this technological determinism in difficult times. Stanhope’s speech, for instance, was made after the apparent setback of the treason trials, when the radical societies needed to believe that the logic of print was being restored to its true course. Hardy saw it being fulfilled when he wrote to congratulate Lafayette on the July Revolution of 1830:

Political knowledge is making a great, and rapid progress. It is now diffused among all classes. The printing press is performing wonders. It was a maxim of the great Lord Bacon that Knowledge is power.69

Such faith was sustaining in the face of repression and after the experience of repeated defeat that Hardy was hoping had finally been overcome. After the passing of the Two Acts at the end of 1795, Thelwall rallied his former colleagues to a belief that reading and discussion, especially his own works, were the way forward. On 15 December 1796, he sent the central committee copies of his recently published Rights of Nature with the following letter:

There is nothing for which I am more anxious than to see the spirit of enquiry revived in our society & prosecuted with all its former ardour. Depend upon it, nothing but information can give us liberty; & however unpromising things may, at this time, to some appear: I cannot but believe that events must be hastning [sic] which will make us wish that the time now lost in wrangling or supineness, had been spent in reading & political discussion, by which our minds might have been prepared for liberty & enabled to obtain it. As a patriotic contribution, towards reviving the discussion so desirable, I present the society with twelve copies [sic] of my first Letter on the Rights of Nature, in answer to Mr. Burke; recommending that twelve readers be appointed by the Committee to read them to the respective divisions, & that the books be of course given to the readers as a trifling compliment for their trouble.70

The idea of the LCS as a society of reading circles – each with its own appointed readers – corroborates Place’s later account of the Society, but seems almost to become an end in itself here, preparatory to some crisis whose coming it seems to have no very obvious active relation to. Faced by the restrictions brought in by the Two Acts, Thelwall counsels trusting to a deeper narrative of the power of print and discussion, rather than any particular form of political organisation to specific ends. Against that, it must be said, Thelwall does not present reading as a retreat into self-improvement, but as part of an ongoing public commitment, to reading as dissemination, even if its relationship to political change seems more occluded than it had in his lectures of 1794 and 1795. He pays an attention typical of the LCS to the disposition of the reading and discussion of his work. This kind of more practical awareness of the need to organise and work with the means of dissemination was not uncommonly intertwined with the technological determinism that I call print magic.

At their most declamatory, radical orators represented resistance to their political cause as an impossible attempt to restrain the inherently progressive drive of print dissemination. From this position, government attempts to control the radical press were foolish attempts to turn back history itself, ripe for satires like Eaton’s The Pernicious Effects of the Art of Printing (1794). Longing for the return of the dark night of the Stuarts, the authorial persona ‘Antitype’ rails against the magical power of print:

before this diabolical Art was introduced among men, there was social order; and as the great Locke expresses it, some subordination-man placed an implicit confidence in his temporal and spiritual directors – Princes and Priests – entertained no doubts of their infallibility; or ever questioned their unerring wisdom.71

On one level, the ironies of the pamphlet may work to suggest that print magic was a mere sham, a Whig myth to be exploded by Eaton’s corrosive satirical method. Pernicious Effects reveals that the elite had never really believed one of the comforting myths of ‘British liberty’. The vaunted freedom of the press, from this perspective, was a smokescreen to distract from the need of the people to assert their rights. On another level, Eaton’s pamphlet may seem to confirm implicitly the basic premise of print magic as a force that can no more be turned back than can the tide. From this perspective, the joke on Antitype is that he can’t see the ineluctable progress of print. His views, Eaton implies, are destined for the dustbin of history.72 In its multiple implications for understanding the power of the medium, Eaton’s pamphlet highlights some of the tensions between the radical commitment to working in print and the technological determinism identified by Warner.

In practice, Eaton never trusted that freedom would come simply through the circulation of what the SCI and LCS called ‘political information’ (the primary form of most of their official publications). As someone who was still involved in radical print culture up to his death in 1814, Eaton might be placed among the honourable company who created the disposition of post-1815 radicalism towards press freedom described by Kevin Gilmartin: ‘The recognition (and experience) of press corruption went a long way towards discouraging strictly determinist attitudes: attention shifted from the nature of the technology to the conditions under which it developed.’73 Certainly Eaton showed an unparalleled ability to adapt print to circumstance in order to sustain what Stanhope called its ‘energy and effect’. For Stanhope himself, the principle of the liberty of the press, with the constitution behind it, was the legitimate idea that could impart this energy and restore British liberty. Eaton, in contrast, was quick to realise the potential of irony as a resource. Well he might, given that the principles of the free press proved far less protective of him than a noble lord. Eaton’s engagement with print often took the form of hand-to-hand combat with the Association for Preserving Liberty and Property against Republicans and Levellers, founded in November 1792. He deployed whatever weapons lay to hand in the armoury of print, often appropriating the satirical methods of earlier participants, including Marvell, Pope, and Swift, regardless of their original political sympathies.

Since the abolition of the Licensing Act at the end of the seventeenth century, the chief means for controlling political opinion had been the law of seditious libel. This legal condition had already shaped the nature of print culture for many decades before the prosecutions of Paine and his publishers in 1792.74 Many of the techniques developed by Eaton and others drew on this archive of resistance, but they were quick to adapt and disseminate them to a wider audience. Legal procedure meant that the indictment prepared for any sedition trial had to include exact statements of the libel being prosecuted. February 1793 saw Thomas Spence acquitted of selling Rights of Man because the book was misquoted in the indictment. The situation was even more complicated in prosecutions that depended on the interpretation of figurative or ironic material. Eaton’s trial in February 1794 for publishing the ‘King Chaunticlere’ allegory became the most celebrated instance. On 16 November 1793, Eaton’s Politics for the People carried a story based on a Thelwall performance at the Capel Court debating society.75 Thelwall’s allegory told the story of a tyrannical gamecock,

a haughty sanguinary tyrant, nursed in blood and slaughter from his infancy – fond of foreign wars and domestic rebellions, into which he would sometimes drive his subjects, by his oppressive obstinacy, in hopes that he might increase his power and glory by their suppression.

The government claimed that the allegory as printed by Eaton libelled George III. In such cases, the prosecution had to specify exactly what construction they were putting on the passages named in the indictment. The glosses or ‘innuendoes’ that appear on the charge were requirements of the legal process: the first reference to the ‘gamecock’ in the indictment was followed by an innuendo explaining the phrase as being used ‘to denote and represent our said lord the king’.

John Gurney’s brilliant defence of Eaton secured an acquittal. The prosecution had gone so far in its eagerness to find libels, argued Gurney, that they had ‘set themselves to work to make one’. More obvious, he argued, to see the gamecock as Louis XVI, or tyrants in general, than George III, who surely, he added archly, could not be understood as a tyrant.76 The growing self-consciousness of radicals about the manufacture of libels – as they saw it – can be glimpsed in the fact that just three issues before ‘King Chaunticlere’, Eaton had already published a sonnet ‘What Makes a Libel? A Fable’:

If Eaton had published Thelwall’s allegory in full awareness of the defence that could be provided for it, as the sonnet suggests, others quickly picked up on his example. Soon after Eaton’s acquittal, for instance, Thomas Spence published two pages under the title ‘Examples of Safe Printing’, framed as a response to ‘these prosecuting times’. They included a passage from Spenser’s The Faerie Queene glossed by bogus innuendoes pretending to distance the poem from any malicious intent:

[Not meaning our most gracious sovereign Lord the King, or the Government of this country]

Spence is alerting his readers to the possibilities of the medium and what can be said by not saying what one means:

Let us, O ye humble Britons be careful to shew what we do not mean, that the Attorney General may not, in his Indictments, do it for us.

If there was a kind of print magic being conjured here, it was far from being a simple faith that it was enough to print the truth for it to be victorious.78

Spatial politics

Print made it possible for radicals to imagine themselves addressing a potentially limitless category of ‘the people’ and for their readers to imagine themselves as subjects within this category, but these relationships were not experienced as an impersonal information economy or an anonymous public sphere. Personality was one diversifying element within the radical print economy, tracked in four detailed examples in Part II of this book. So too was the variety of spaces wherein readers encountered print and met to debate and discuss it with each other. The radical societies imagined themselves as disseminating political information through a world where print and improvements in transport and communications made ‘the people’ a more knowable entity than it had ever previously been. The mail coach system, introduced in 1784 by John Palmer, ‘provided unprecedented opportunity for “correspondence” and for the diffusion of radical material beyond its metropolitan strongholds’.79 This speeding up of communication was a crucial part of the context that recommended the electrical metaphor of political sympathy’s rapid movement from breast to breast. Such ideas were reinforced at LCS open meetings, where the radical societies could show themselves to be ‘public’ institutions, rather than a conspiratorial underground their opponents often claimed, but these were only perhaps the most obvious of a range of locations constructed and inhabited by the SCI and LCS.

Location is an important issue for thinking about radical culture. The venues where things happened or were imagined to be happening changed their meanings, an issue that had legal status when it came to questions of innocence or guilt in trials for sedition and treason, as we shall see. Theories of the role of space in the production of social meaning now abound, but in the 1790s places were inevitably fought over as part of a process of establishing the political geography of London. Spaces were contested most obviously in competitions over occupancy. Debating societies were systematically driven from public houses over 1792–3. More complex to resolve were questions of how spaces were understood and perceived. The LCS’s idea of itself as improving, for instance, meant that it also produced various spaces in the image of the associational worlds of the eighteenth century, actively participating, as it saw it, in the wider political nation. In 1797, for instance, the informer (never uncovered by his comrades), clerk, and aspiring playwright James Powell wrote to Richard Ford his paymaster in the Treasury Solicitor’s office asking for his promised remuneration.80 Powell’s plaintive letter gives an insight into some of the aspirations of those associated with the LCS, and some of the complexities involved in understanding the spaces of popular radicalism.

Powell records expenses involved in setting up a ‘conversatione’ that he boasted was more numerously attended than one Thelwall inaugurated after his acquittal. Among those who attended Powell’s gathering was Citizen Lee, who became ‘a constant attendant on that evening but on every other when I was not at home’. When Lee fled to America at the beginning of 1796, he went with Powell’s wife. Perhaps more surprisingly, at the time of the ‘conversatione’, early in 1795, Godwin seems to have been meeting with LCS members as a group, including Powell, Thelwall, and probably Citizen Lee. The entry in Godwin’s diary for 17 January refers to ‘tea Powel's, w. Ht, Thelwal, Iliff, Bailey, Walker, Manning, Hubbard, Lee, Johns, Fawcet & Dyer’. A similar cast also assembled on the last day of the month: ‘tea Powel’s, w. Thelwal, Bailey, Hubbard, Vincent, Hunter, G Richter, Walker, Bone, Manning & Lee’.

Meeting with LCS members may have been an attempt at Godwin’s ‘collision of mind with mind’.81 No doubt the members of the LCS who attended these meetings were thrilled at the chance to meet the philosopher, which is not to say that they necessarily agreed with his ideas. Tea with Godwin did at least provide an opportunity for the LCS men to demonstrate that they were quite as capable as he of sustaining intellectual improvement. The question of Godwin’s influence in the LCS is a topic for later on, but for now I want to pause over Powell’s letter and read it with the brief entry in Godwin’s diary. On the face of it, Powell’s provision of ‘bread & cheese & porter’ might seem appropriate for members of an organisation often identified with the culture of the alehouse. ‘Tea’, the term used in Godwin’s diary, on the other hand, suggests something more ‘polite’, perhaps ‘domestic’ even, as if Powell had got the best china out to welcome the famous political philosopher, but this juxtaposition would imply too crude an opposition between ‘polite’ and ‘popular’. Powell almost certainly knew Godwin before January 1795. He was from a respectable background; at least his father had been a clerk in the Customs House, ‘a man of property’, Francis Place claimed.82 Powell certainly harboured literary ambitions, as did others who attended the meeting with Godwin, including Thelwall and Citizen Lee.83 Secondly, Powell’s ‘conversatione’ took place not in an alehouse, but in a ‘private’ or ‘domestic’ context. Powell’s wife was evidently a regular presence. Whether she was a participant or someone whose domestic labour facilitated the event and added to its politeness is not known. Many years later Francis Place – who dismissed Powell as ‘honest, but silly’, still not knowing him to have been a spy – claimed she was ‘a woman of the town’.84 Regardless of Place’s judgement, the Powells quite probably aspired to rational improvement of the sort Godwin wrote about in Political justice.

‘Tea’ is Godwin’s description of his meeting at Powell’s, but the word needs careful treatment. The evidence of the diary is that it may simply be Godwin’s general word for any modest repast served in the home (in late afternoon). In the diary, it is often used for meetings that included the consideration of weighty philosophical questions (often in mixed company), and need not imply politeness in a way that militated against the vigorous discussion of political issues. Take, for instance, the ‘tea’ at ‘Barbauld’s w. Belsham, Carr, Shiel, Notcut & Aikin jr’, on 29 October 1795, where Godwin and his friends ‘talk of self-delusion & gen principles’. The same was true at Helen Maria Williams’s salon, which aspired to rather more in terms of intellectual exchange than the word ‘politeness’ may sometimes seem to imply. All these occasions seem to have allowed for the collision of mind with mind, to some degree at least, within the home, even if not within strictly ‘domestic’ circumstances. For my purposes, the main point is that the LCS and its members involved themselves in the diffusion of knowledge across a diversified urban terrain, which included their homes. The conversaziones held by Powell, Thelwall, and others were intrinsic to their commitment to ‘reform’. They were one of many spaces beyond LCS meetings proper, but produced by their activity, where ideas were hammered out and solidarity cemented in a convivial environment. Convivial these spaces may have been, but they were also often contested, usually threatened by surveillance, and sometimes even violently interrupted by law officers and their minions.

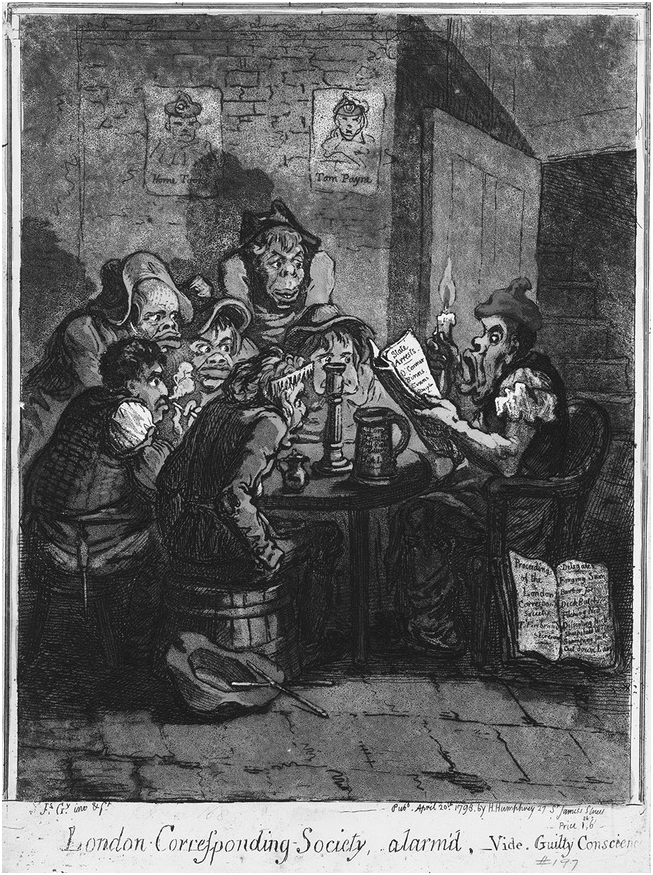

Epstein has argued for a better understanding of the relationship ‘between the logic of spatial practices and language, or better the production of meanings’. Radical culture in the 1790s provides Epstein’s key examples of ‘naming, mapping, tracking, settling, imagining and counter-imagining’ as it played out in ‘taverns, courtrooms and the street’. Following Michel de Certeau’s understanding of ‘space’ as ‘practiced place’, Epstein relates spatial production to ‘democratic political practice, possibilities of representation, and visions of possibility’.85 The ambit of these practices included spaces beyond the tavern and the street, including the bookshop and the theatre, and even, for instance, prisons. No less important were everyday places where the practices of taking ‘tea’ or ‘bread & cheese & porter’ might give a cast to understanding the activities of the LCS very different from the hostile representations found, for instance, in Gillray’s The London-Corresponding-Society alarm’d (Figure 3). Gillray’s representation of the spatial practices of the LCS as subhuman and beneath contempt, of course, was easier to sustain after the Two Acts had in one sense driven the LCS underground, although in publications like John Gale Jones’s Sketch of a political tour (1796) the LCS continued to imagine the development of a public sphere out of the interactions between citizens in a variety of places beyond the alehouse, including a stage coach, a circulating library, and even a dance at a public assembly.86

Fig 3 James Gillray, London-Corresponding-Society alarm’d: vide guilty consciences [1798].

Eighteenth-century spaces such as taverns and coffee houses have been understood in Habermasian terms as arenas of ‘conviviality where ideas circulate freely among equals’.87 London’s debating societies may seem to be the apotheosis of this idea, but they were subject to an ongoing commentary about their respectability before the 1790s. After the royal proclamations against seditious writings in May and November 1792, they were very much subject not only to surveillance, but also direct and often violent interventions in their proceedings. The reports the spy Captain George Munro sent into the Home Office in November 1792 often struggle to fit his understanding of popular culture with what he saw at the LCS’s own debates. He melodramatically described the meeting he saw at the Cock and Crown tavern as a gathering of the ‘lowest tradesmen, all continually smoaking and drinking porter’, but then concedes they were ‘extremely civil’.88 Such concessions were rare in spy reports. When he started reporting in February 1794, John Groves insisted that it ‘requires some mastery over that innate pride, which every well-educated man must naturally possess, even to sit down in their company’.89 Perhaps more anxious about his social status than Munro, Groves may have felt a social pressure to confirm to his masters that he was of a different order from the men he was reporting on. How such men managed to organise themselves into their own version of the public sphere continued to puzzle polite commentators and the government alike.

John Barrell has provided a nuanced map of LCS organisation across London boroughs.90 My concern is less with geography than with the production and contestation of different kinds of space. Michael T. Davis has shown the importance of ‘the politics of civility’ in the LCS. Thomas Hardy’s account of the first ‘public’ meeting – in the Bell on Exeter Street off the Strand – described the participants as ‘plain, homely citizens’.91 The Bell may very well have been neat and ‘homely’ compared to some of the alehouses where LCS divisions met. Newman rightly points out that distinctions between alehouses and taverns have often been flattened out in analysis.92 Davis notes how much of the LCS’s official documentation is concerned with the orderliness that Place was keen to stress in his Autobiography. Davis primarily understands these self-representations as the product of the LCS’s need ‘to represent itself as inclusive, autonomous, as a rule-regulated organization based upon the principle of equality and rational deliberation in order to invert the political messages of loyalists’.93 This idea of civility extended even to prison sociability, which included visits from Godwin, Amelia Alderson, and various other literary figures sympathetic to reform.94

The LCS frequently did represent its own behaviour as intended to ‘defeat the various calumnies with which they have been loaded by the advocates of Tyranny & Oppression’.95 But this self-representation should not be understood only as a functional need to demonstrate its respectability. There is a danger of constructing the LCS as most authentically itself when involved in ‘unrespectable’ tavern-based activities, as I have already mentioned, and somehow only deferring to external notions of respectability when it met in more disciplined social forms. Quite apart from the practicalities involved in running business meetings, the LCS carried on the popular aspect of enlightenment that saw ‘reform’ as an opportunity for participation across a diversity of social worlds from debating societies to other forms of print sociability. Lydia and Thomas Hardy (as abolitionists), Citizen Lee (as an evangelical poet, first published under the sponsorship of the Evangelical Magazine), and John Thelwall (as a member of debating and numerous other literary and scientific societies) all participated in such worlds before they joined the radical societies. Each saw the LCS as an extension of their commitment to a spirit of improvement, however variously understood.

Long before the 1790s, the contact zones of urban leisure were already subject to complex pressures of policing, representation, and interpretation. In 1781, David Turner, president of the Westminster Forum, presented its debates as a site for the integration of what he calls ‘public conversation’, but acknowledged that sometimes they failed to transcend their ‘ale-house’ (Turner’s word) associations. The roughness of the debates, Turner believed, discouraged some of those capable of ‘classical erudition’ from attending, although he insisted that plenty of the educated classes did go.96 Several times Turner mentions the presence of women at the debates. On one occasion, in response to a remark on the growth of population, ‘the brilliant set of ladies in the gallery, spread their fans before their faces’.97 The presence of women was always crucial to how meaning was constructed in social space. They could grant an aura of respectability, although for some commentators their presence could itself function as a sign of transgression. Powell’s wife may have passed from one to the other pole of this representation during the life of his conversazione. Her disappearance with Lee into exile in America may have confirmed her status as a ‘woman of the town’ from Place’s point of view, but to others her presence at Powell’s gatherings may have conferred politeness on them.

The spatial definitions of such places could have very real consequences for radical groups, as the case of John Frost shows.98 Frost was an attorney who had been closely involved with the SCI from its beginnings in the 1780s and played an important role in its revival under Horne Tooke’s leadership in 1791. When Paine left for Paris in September 1792, Frost accompanied him, writing back regularly to Horne Tooke to describe their progress. Returning to London in October, Frost sat on the SCI committee chosen to confer with the LCS over addressing the French Convention. Reporting on Frost’s speech to an LCS meeting a few weeks later, the spy Munro described him as ‘almost the only decent Man I have seen in any of their Divisions’. The SCI chose Frost with Joel Barlow to deliver their address to the Convention (and a consignment of a thousand pairs of shoes for the French army). Munro’s report of the event from Paris maliciously described Frost being mistaken for a shoemaker by the Convention’s deputies.99 On 6 November between his two trips to Paris, Frost had attended the dinner of an agricultural society at the Percy, a fashionable London coffee house. On his way out, he was stopped by the apothecary Matthew Yateman and asked about France. The two men already knew each other, but their conversation grew heated after Frost told Yateman ‘I am for Equality and no King.’ When Yateman asked if he meant ‘no King in this country’, Frost is said to have bawled out ‘no Kings in Englands’. At this point, according to their evidence in court, others became involved in the fracas. Although a complaint against Frost was made immediately, the government did not take any action until it was sure he was back in France. A price was put on his head, but Frost wrote from Paris vehemently denying that he had fled justice, and reminding Pitt that they had at one time attended the same meetings in favour of reform. Almost certainly the government wished to avoid a trial, not least because of Frost’s possession of correspondence with Pitt from the 1780s, later reprinted in the proceedings of the trial. Probably to dissuade Frost from returning, the government newspapers began suggesting that he had fled to avoid bankruptcy. His wife Eliza informed the Morning Chronicle that he was solvent, which Frost proved on his reappearance. With Frost back in London, stalemate ensued. Sheridan queried the silence on the case in Parliament on 4 March to suggest that the government now wished to drop it.

When the trial did finally commence two months later, Thomas Erskine’s defence strategy turned on two issues. The first was whether Frost spoke ‘advisedly’, that is, whether he could be charged with intentionally aiming to spread disaffection if he had been in drink. The second part of the defence depended upon understanding the space of the coffee house as ‘private’ and properly beyond the reach of a law on seditious words. Erskine insisted that the ‘common and private intercourses of life’ were protected from prosecution:

Does any man put such constraints upon himself in the most private moments of his life, that he would be contented to have his loosest and lightest words recorded, and set in array against him in a Court of Justice?