1.1 Introduction

Climate change governance has been more than 30 years in the making, but it remains a work in progress. The international climate regime, centred on the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), has been heavily criticised for being too slow to produce results (Victor, Reference Victor2011). In spite of all the resources – time, money, personal reputations – that have been painstakingly invested in the climate change regime, global emissions have still not peaked. Scientists have repeatedly sounded the alarm about the significant ‘gap’ (UNEP, 2016) between current emissions and what is required to ensure that warming does not exceed two degrees Celsius (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Rayner and Schroeder2013).

The argument that the international regime will not fully accomplish climate governance is not a new one (Okereke et al., Reference Okereke, Bulkeley and Schroeder2009). Over the years, numerous ideas for reform have been floated, many focusing on the various ways in which governance could and should be made more diverse and multilevel (Rayner, Reference Rayner2010). In the late 2000s, Elinor Ostrom was at the forefront of those arguing that ‘new’ and more dynamic forms of governing climate change were not just possible or even necessary, but were in fact already appearing around, below and to the side of the UNFCCC. Her message was a positive one: not all aspects of governance would have to be painstakingly designed by international negotiators. New forms were, she argued, emerging spontaneously from the bottom up, producing a more dispersed and multilevel pattern of governing, which she described as ‘polycentric’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a).

Since then, many others have made very similar remarks. Keohane and Victor (Reference Keohane and Victor2011: 12) have, for example, likened the growth in the number of new governance initiatives to a ‘Cambrian explosion’. As analysts, we are beginning to learn that much of this ‘groundswell’ (Falkner, Reference Falkner2016) of new activity emerged in the past decade and is conventional in the sense that it links different forms of state-led governing (e.g. government-driven coalitions promoting carbon pricing such as the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, or the European Commission collaborating with mayors in cities through the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy). But it is also becoming clear that many others are adopting more novel, hybrid forms (e.g. international standards developed by non-state actors, or subnational governments collaborating across borders without the involvement of their national governments). Again, Elinor Ostrom’s message was unashamedly positive: she suggested that these activities, although initially small in size and few in number, would become ‘cumulatively additive’ over time (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a: 551, 555). Polycentric climate governance had emerged and was ‘likely to expand in the future’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a: 555).

Recent developments within the UNFCCC itself appear to confirm the trend towards greater polycentricity. At the 2015 climate summit in Paris, world leaders agreed to establish a more bottom-up system of governance through which states would pledge to make emission reductions, then gradually ratchet them up as part of a process of ongoing assessment and review (Keohane and Oppenheimer, Reference Keohane and Oppenheimer2016). Crucially, the Paris Agreement also offered strong encouragement to existing and new climate actions by non-state and subnational actors (Hale, Reference Hale2016), thus underlining the importance of the general trend towards greater polycentricity.

Ostrom’s contribution to these debates lays not so much in establishing new theoretical perspectives – she borrowed the term polycentric from a much older literature on the governance of local problems in urban American contexts (Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren, Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961) – but in sensing that the climate governance landscape was in transition and asking whether it could be better understood by employing new, i.e. polycentric, terms and concepts. She also directly questioned the way in which the climate governance challenge has conventionally been framed, i.e. how to deliver a global public good (a habitable climate) by coordinating state action through a strong international regime. By contrast, her reference point was polycentric systems, which she characterised as

multiple governing authorities at different scales rather than a mono-centric unit. Each unit within a polycentric system exercises considerable independence to make norms and rules within a specific domain (such as a family, a firm, a local government, a network of local governments, a state or province, a region, a national government, or an international regime).

As can be inferred from this quotation, the logical opposite of a polycentric system is a monocentric one, i.e. controlled by a single unitary power (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 244). In the area of climate change, it is hard to pinpoint a pure form of monocentric governance, but the Kyoto Protocol–based approach, involving legally binding international treaties with quantified emission goals, is possibly the closest approximation (Osofsky, Reference Osofsky, Farber and Peeters2016: 334; for a more extensive discussion, see Chapter 2).

Ostrom’s empirical approach to documenting climate governance was also unconventional. Rather than start with the UNFCCC and work downwards, her entry point was the actually existing forms of governance that were being constructed by myriad actors, operating in different sectors and across different scales; her illustrative examples were from the state level in the United States, from several large cities and from the European Union (EU) (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a: 553). To be sure, she never claimed that polycentric governance would be perfect or a substitute for international diplomacy; she believed that various governance activities from multiple jurisdictions and levels, arranged in a polycentric pattern, had the potential to be highly complementary (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a: 552, 555). She was also rather guarded in her claims on whether polycentric governance would significantly reduce emissions: any reductions may only be ‘slowly cumulating’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a: 553). In this vein, she made a strong case for undertaking further empirical work on the actual, long-term impact of the new polycentric initiatives that were appearing. In her own mind, she envisaged a new programme of empirical work on these topics; in fact she thought that an inventory of polycentric actions ‘would be a good subject for a future research project’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2009: 19). Unfortunately, she passed away before she could complete that task.

Even if Elinor Ostrom did not invent the term polycentric, and climate change only really preoccupied her during the latter stages of her long career, her interventions in the debate have undoubtedly stimulated others to critically reflect upon various taken-for-granted assumptions in climate governance research and practice. In the late 2000s, the proliferation of initiatives was widely perceived as a negative development – a ‘fragmentation’ of and possibly a distraction from international efforts (Biermann et al., Reference Biermann, Pattberg, van Asselt and Zelli2009). Those who actually studied the new initiatives in more detail were more sanguine, but often regarded them as alternatives to the apparently gridlocked global regime (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011). Ostrom was more open-minded about the precise relationship between the various levels, units and domains; she saw it as an empirical matter. But among the very many articles and books published since her death, none has really taken forward the broad research programme that she originally envisaged. In fact, such has been the growth in the scale and scope of climate governance in the past decade that such a task could not possibly be accomplished in a single project.

This book is a first attempt to make some headway in addressing this challenge. Our primary aim is to explore what is to be gained by thinking about climate governance as an evolving polycentric system. In a descriptive sense, this book investigates what a polycentric perspective adds to our ability to characterise and make sense of climate governance in toto. Recent research suggests that the various domains Ostrom identified are more interconnected and interlinked than was originally thought (Betsill et al., Reference Betsill, Dubash and Paterson2015), but it tends to look only at one or two domains at a time. Crucially, even a combination of partial perspectives is, we think, unlikely to reveal if and how governance functions in a polycentric system.

From an explanatory perspective, we have already noted that Ostrom’s notion of polycentricity is at odds with the way in which climate governance has traditionally been studied and enacted, with the UNFCCC presumed to be at its ‘core’ (Betsill et al., Reference Betsill, Dubash and Paterson2015: 2). It directly challenges the manner in which academic activities have conventionally been subdivided (into those focusing on international, national and/or subnational levels, or private and/or public spheres). It also has potentially far-reaching implications for our appreciation of important matters such as authority and power, accountability, legitimacy and innovativeness. If governance is more polycentric, where does authority actually reside, is it possible to arrive at an overall measure of effectiveness and how is governing legitimated? Does the apparent dispersal of authority involve greater mutual adjustment between the domains (i.e. a ‘race to the top’), or one in which standards are lowered to attract resources such as inward investment (i.e. a ‘race to the bottom’)? At present, scholars have barely begun to think about these more systemic issues (but see Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Huitema and Hildén2015).

Finally, as a normative source of prescriptions on how better to govern, polycentric governance thinking provides a rather different starting point to other stock-in-trade terms and concepts. Under the more monocentric or ‘Kyoto’ model of governing, it was more or less clear who was doing the governing (i.e. states). It was therefore obvious who or what would ultimately be held accountable; what innovativeness in governing meant (a better international regime) and where it was most likely to derive from (namely the UNFCCC, informed by the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change);1 what the chief metric of effectiveness was (reducing emissions); and how governing would be legitimated (through forms of democratic statehood). Thinking about what it means to govern polycentrically entails a revision of these starting assumptions. In addition, polycentric governance thinking is much more tolerant of overlap, redundancy and duplication in governance. The fact that multiple governing units take initiatives at the same time is seen not as inefficient and fragmented, but as an opportunity for learning about what works best in different domains.

The remainder of this chapter unfolds as follows. Section 1.2 charts the changing landscape of climate governance in more detail. It identifies the main actors and forms of governing – a task that is more fully accomplished in Part II of this book. Section 1.3 examines the intellectual origins of polycentric thought in more detail and identifies five of its most important propositions. Section 1.4 concludes by outlining the four main objectives of the whole book.

1.2 Climate Governance

1.2.1 A Landscape in Transition?

The conventional way in which shifts in climate governance have been described is to start with the highest level (at least in a spatial sense) – the international regime – and work downwards and then outwards. From the perspective of the regime, climate change is first and foremost a global problem, requiring states to overcome significant collective action problems principally by negotiating credible agreements. However, as noted earlier in this chapter, recent scholarship has begun to reveal a rather different picture. For example, governance is no longer seen as the prerogative of states or the UNFCCC, thus requiring much greater awareness of the linkages with other regimes governing inter alia trade, investment and human rights (Moncel and van Asselt, Reference Moncel and van Asselt2012). Keohane and Victor (Reference Keohane and Victor2011: 7) have distinguished between a single climate regime and a regime complex ‘which [has] emerged as a result of many choices … at different times and on different specific issues’. The emergence of interacting (complexes of) regimes has in turn stimulated work on how to address institutional fragmentation (Zelli and van Asselt, Reference Zelli and van Asselt2013). Scholars have reflected on how fragmentation gives actors more opportunities to ‘venue shop’ and/or engage in credit-claiming and/or blame-avoidance games (Gehring and Faude, Reference Gehring and Faude2014: 472). Although the starting assumptions of this work were different, the emerging picture is one that has many similarities with Elinor Ostrom’s more polycentric view.

These observations are being taken forward in the wake of the Paris Agreement. Although that agreement emerged from a process of intergovernmental negotiation, it undoubtedly broke new ground (Falkner, Reference Falkner2016). In the past, it was widely assumed that states would only take on emission reduction targets after long and tortuous processes of bargaining. In practice, the targets were unenforceable, and several major polluters (e.g. the United States and Canada) simply walked away. The Paris Agreement tacitly accepted this realpolitik – henceforth, states will simply pledge to make emission cuts, enshrined in what are known as nationally determined contributions. Interestingly, non-state actors are developing new ways to evaluate state behaviour in the pledging process, itself wrapped up in a five-yearly global stocktake of all pledges (Schoenefeld, Hildén and Jordan, Reference Schoenefeld, Hildén and Jordan2018).

Moving down a level, new insights are also being generated into the public policy–making activities of states. Amongst international policy scholars, states are only really important because they negotiate regimes. Since Paris, however, their inner workings have become a much more popular object of attention (Jordan and Huitema, Reference Jordan and Huitema2014a, Reference Jordan and Huitema2014b; Bang, Underdal and Andresen, Reference Bang, Underdal and Andresen2015). The ‘Climate Change Laws of the World’ database reveals that by 2017, 1,200 individual climate laws and policies had been adopted (Averchenkova, Fankhauser and Nachmany, Reference Averchenkova, Fankhauser, Nachmany, Averchenkova, Fankhauser and Nachmany.2017), up from only 60 when the Kyoto Protocol was signed in 1997. The most active adopters have up to 20 separate climate laws on their statute books (Averchenkova et al., Reference Averchenkova, Fankhauser, Nachmany, Averchenkova, Fankhauser and Nachmany.2017: 15). Meanwhile, the judiciary within states has also become more active, complementing and on occasions also substituting for national legislation (Averchenkova et al., Reference Averchenkova, Fankhauser, Nachmany, Averchenkova, Fankhauser and Nachmany.2017: 13). These legislative activities also extend to adaptation to climate impacts (Massey et al., Reference Massey, Biesbroek, Huitema and Jordan2014).

As Ostrom foretold, many states are evidently not waiting for the international regime to push them to act. In fact, there even appears to be evidence of greater polycentricity within the relatively monocentric domain of state-led policymaking. For example, more than 100 regional governments have committed themselves to reducing emissions by at least 80 per cent by 2050, a target exceeding that of most sovereign states (Averchenkova et al., Reference Averchenkova, Fankhauser, Nachmany, Averchenkova, Fankhauser and Nachmany.2017: 12). States are also not moving forward at the same rate: industrialised countries are more active adopters of climate laws than developing countries, a significant number of whom have failed to adopt a single instrument. Even the type of national policies is quite heavily differentiated between those that are binding (and hence more monocentric) and those that are not (Averchenkova et al., Reference Averchenkova, Fankhauser, Nachmany, Averchenkova, Fankhauser and Nachmany.2017).

If one moves outwards into the domain of private governance, yet more forms of governing come into view, again reinforcing the impression that the degree of polycentricity is rising. These include voluntary commitments to reduce emissions, but also highly complex systems for monitoring and trading in emissions, and efforts to disclose the carbon risks for businesses and investors (Green, Reference Green2014). It has long been recognised that private actors will eventually deliver a great deal of mitigation and adaptation, but the breadth and ambition of what many are now offering demands greater explanatory attention. Many of the private initiatives are being steered by industry associations and alliances, seemingly independent of state action but at the same time interacting with such action in unknown ways. For instance, the World Business Council on Sustainable Development coordinates Action 2020, an initiative to embed sustainability in business practices, as well as more sector-specific activities, such as the Cement Sustainability Initiative. To give another example, as part of the Science-Based Targets initiative, a partnership formed by the United Nations and several business and environmental organisations, more than 200 of the world’s largest and most energy-intensive companies have voluntarily taken on 2050 reduction targets based on their share of the global reductions needed to stay within two degrees. These types of private action have been interpreted as yet more examples of polycentricity in action (Cole, Reference Cole2011).

It was therefore a natural next step for some analysts to explore the linkages and interactions between the various actions and initiatives (Betsill et al., Reference Betsill, Dubash and Paterson2015). Such work is revealing that some of the initiatives are linked in ways that bypass state control. Bulkeley et al. (Reference Bulkeley, Andonova and Betsill2014) have characterised these as hybrid or transnational forms of governance. Some initiatives even perform functions (e.g. standard setting) that have traditionally been monopolised by states (which in practice still need to sanction such standards to enhance legitimacy).

Practitioners too have acknowledged that polycentricity should be taken much more seriously. Some of these efforts date back to the early 2010s, but accelerated prior to the Paris summit (Hsu, et al., Reference Hsu, Moffat, Weinfurter and Schwarz2015; Hale, Reference Hale2016). In fact, the Paris outcomes actively encourage the development of new forms of governing via annual events and technical expert meetings. An online portal has been established for non-state and subnational actors to register their emission reduction commitments (the Non-state Actor Zone for Climate Action). And two rotating ‘high-level champions’ have been asked to encourage further action by non-state and subnational actors. Therefore, it seems as though the UNFCCC is itself adjusting, from the setting of global rules to the more polycentric task of facilitating non-state action.

1.2.2 The Struggle to Understand the Changing Landscape

Clearly, the governance landscape is in flux: more actors are engaging in many more activities at significantly more levels of governance. According to Betsill et al. (Reference Betsill, Dubash and Paterson2015: 8), the emerging landscape

will only get more complicated over time. The ability to work out how its different elements interact, and thus how they may be enabled to interact more effectively, is … likely to become an ever more pressing question for both.

How are researchers rising to these challenges? The proliferation of terms suggests that scholars do not yet agree on what constitutes ‘the landscape’. Among international scholars, new terms have been coined, including ‘regime complexes’ (Keohane and Victor, Reference Keohane and Victor2011), ‘experimentalist’ (Sabel and Zeitlin, Reference Sabel, Zeitlin and Levi-Faur2009), ‘complex’ (Bernstein and Cashore, Reference Bernstein and Cashore2012) and ‘fragmented’ governance (Zelli and van Asselt, Reference Zelli and van Asselt2013). For those interested in national political systems, state policies are of paramount importance, hence references to climate policy innovation (Jordan and Huitema, Reference Jordan and Huitema2014a, Reference Jordan and Huitema2014b), experimentation and the new climate governance (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Huitema and Hildén2015).

By consciously selecting the term polycentric, Elinor Ostrom sought to unify these debates. As we suggested earlier, she saw a need for a more holistic description of the landscape, for more analysis (to understand and explain its functioning) and better prescription (grounded in a different normative framework). Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2010a: 552) claimed that polycentric systems are capable of enhancing ‘innovation, learning, adaptation, trustworthiness, levels of cooperation of participants, and the achievement of more effective, equitable, and sustainable outcomes at multiple scales’. Some polycentric thinkers have examined parts of the landscape and declared that it is already being governed more or less as she predicted (Cole, Reference Cole2015), and even that ‘effective global governance institutions inevitably are polycentric in nature’ (Cole, Reference Cole2011: 396, emphasis added).

But the conditions under which these and other effects are produced is surely a matter for more detailed empirical research. This was certainly Vincent Ostrom’s starting position (Ostrom et al., Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961: 831). He asserted that ‘[n]o a priori judgement can be made about the adequacy of a polycentric system of government as against the single jurisdiction’ (838). Elinor Ostrom also underlined the importance of studying the strengths and the weaknesses of polycentric governance empirically (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a: 555), and with an open and critical eye. But since then, too many researchers seem to have forgotten this, treating her predictions as things to be empirically confirmed rather than rigorously tested for.

In order to treat her claims in the rigorous manner in which she conducted her own work, it is important to be clear about what we mean by governance and, more specifically, polycentric governance. To be fair, there is no single, canonical theoretical statement of either term (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016: 5). Some have argued that the Ostroms were too quick to put aside theoretical-conceptual matters in the quest for empirical verification, leaving the theory somewhat underspecified (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 248). And then of course work originally conducted by the Ostroms has been taken up and amended by others in the Bloomington School (e.g. compare Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 241–244; McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016). This process of reapplication and refinement has further blurred the three core functions of polycentric thinking (description, explanation and prescription; McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016: 2), to the evident frustration of those who want to engage in new work (Galaz et al., Reference Galaz, Crona, Osterblom, Olsson and Folke2012; Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017). For example, absolutely core terms such as ‘polycentric’, ‘polycentricity’ and ‘polycentrism’ are used quite casually in the existing literature. Therefore, the next section tries to unpack the concept of polycentric governance and explicate five of its most important theoretical propositions.

1.3 Polycentric Governance: Pedigree and Propositions

1.3.1 Origins and Antecedents

Following Kooiman (Reference Kooiman1993), governing can be defined as directed behaviour, involving governmental and non-governmental actors, which is aimed at addressing a particular issue. Governance involves the creation of institutions – rules, organisations and policies – that seek to stabilise (or govern) those behaviours. The term governance thus describes ‘the patterns that emerge from the governing activities of social, political and administrative actors’ (Kooiman, Reference Kooiman1993: 2). As noted earlier in this chapter, the climate change governance landscape is populated by a wide variety of forms of national, international, private, state-led and transnational governance.

Polycentric governance systems are essentially those in which ‘political authority is dispersed to separately constituted bodies with overlapping jurisdictions that do not stand in hierarchical relationship to each other’ (Skelcher, Reference Skelcher2005: 89). The key operative word here is ‘overlapping’; it means that the scope of the issues that are addressed is not discrete (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016: 7). However, this broad description could conceivably cover many types of governance. We have already noted that one way to understand polycentric systems is to compare them with monocentric ones. Thus, in polycentric systems, the constituent units ‘both compete and cooperate, interact and learn from one another’, so that their responsibilities ‘are tailored to match the scale of the public services they provide’ (Cole, Reference Cole2015: 114). Decades ago, Vincent Ostrom et al. (Reference Ostrom, Tiebout and Warren1961: 831) argued that:

‘[P]olycentric’ connotes many centers of decision-making which are formally independent of each other … To the extent that they take each other into account in competitive relationships, enter into various contractual and cooperative undertakings or have recourse to central mechanisms to resolve conflicts, the various jurisdictions … may be said to function as a ‘system’.

His definition stemmed from work he had conducted on the delivery of public services (such as clean water and policing) in metropolitan areas in the United States. At the time, there was widespread concern that services were being delivered by too many governmental organisations – they were getting in each other’s way (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a: 551) – and that scale enlargement was the way forward (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012). Vincent Ostrom set out to challenge the prevailing orthodoxy that polycentric systems were inherently chaotic and inefficient by undertaking detailed empirical work. He revealed that often the most effective solution was not to consolidate all the organisations into large ‘super’ organisations (what he termed ‘Gargantua’), but to allow a diversity of local approaches to flourish (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 241).

Polycentricity is not, as Galaz et al. (Reference Galaz, Crona, Osterblom, Olsson and Folke2012: 22) have usefully reminded us, a binary variable. In very general terms, it describes the degree of connectedness or structuring of a polycentric domain and/or system. At one extreme are very loose networks of actors and units that engage in very weak forms of coordination based on sharing information in a very passive manner. The interaction between individual units is very limited, as is the level of trust between actors. Insofar as hierarchical organisations are involved in coordinating the participants (i.e. via forms of network management), it is mainly to function as fairly passive clearing houses (Jordan and Schout, Reference Jordan and Schout2006). At the other extreme, we find actors bound together more tightly through more formal systems of coordination. The units actively share information with one another in an atmosphere of greater trust. The participants may even decide to define a common strategy in advance, and have formal, sometimes relatively hierarchical mechanisms to implement it against the wishes of particular units (Jordan and Schout, Reference Jordan and Schout2006). They have many similarities with federal or quasi-federal systems such as the EU (Galaz et al., Reference Galaz, Crona, Osterblom, Olsson and Folke2012: 23). Finally, it is often assumed that polycentric systems are inherently more multilevel than monocentric ones, but this is widely considered to be an empirical question (Galaz et al., Reference Galaz, Crona, Osterblom, Olsson and Folke2012: 29).

1.3.2 Core Propositions

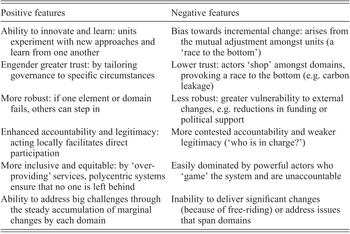

We have already noted the absence of a single, canonical summary of the essential features of polycentric systems (for details, see Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017: 47), or indeed clearly articulated hypotheses (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 248). Some commentators have responded by focusing less on their constitutive processes and more on their positive and negative features (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Polycentric governance: examples of positive and negative features

Although useful, lists such as these struggle to explain why or how the features come about. Some have also noted how polycentric theorists tend to stress the positive aspects over the negative ones (Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017). The fact too that the strengths and weaknesses almost perfectly mirror one another suggests that they may arise from a common set of causal processes. In what follows, therefore, we relate them back to five key propositions in polycentric theory. We discuss each in turn, revealing what they imply for the ways in which climate governance has been – or in future could be – described, explained and designed.

Proposition 1 – Local Action Governance initiatives are likely to take off at a local level through processes of self-organisation.

In many ways, this is the key proposition (Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017: 52). It derives from the work of Polyani (Reference Polyani1951), who argued that polycentric systems operate at two levels: that of individual units and that of the collective. Each individual actor in a polycentric system plots their own actions, based on their own preferences, and responds to external stimuli. They are open to information about the experiences of others, and information about the consequences of their actions, both for themselves and for others. In response, they will adjust their behaviour (or ‘coordinate’) with others. This basic line of reasoning explains why polycentric theorists are less worried about collective action than authors such as Mancur Olson (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016: 16). Indeed, Vincent Ostrom’s early work implied that different public goods can be delivered by different combinations of agencies self-organising on different scales, and that actors (in that case members of the public) will choose accordingly (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2011: 16). Hence, the optimum scale of intervention is not necessarily the same for all services – some may be better delivered at one level, others at another level. Instead of trying to remove overlapping jurisdictions (by integrating governing units into larger bodies), polycentric thinkers try to identify how they coordinate themselves through less hierarchical arrangements (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 242).

Wrapped up in Proposition 1 are a host of related assumptions and truth claims, such as that actors should enjoy the freedom to ‘vote with their feet’ (i.e. ‘Tiebout sorting’; see McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2011: 16) and to identify the best fit between problems and particular units of organisation (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010b: 5). Together they beg the most fundamental question of all: how and why does polycentric governance emerge in the first place (Galaz et al., Reference Galaz, Crona, Osterblom, Olsson and Folke2012: 23)? First, Proposition 1 does not imply that self-organisation necessarily always produces a socially optimum outcome – only that it emerges from the bottom up (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2005: 14). Second, it does not necessarily imply that all actors have the capacity or the motivation to self-organise, hence the need for facilitators or civic (or policy) entrepreneurs in certain situations (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016: 12, 16). Third, Proposition 1 does not imply that all coordination challenges magically self-correct, only that self-organisation generates new coordination challenges as well as new means to address them (Peters, Reference Peters2013: 572).

Elinor Ostrom directly cited Proposition 1 in her very first publication on climate change: ‘Part of the problem is that “the problem” [of climate change] has been framed so often as a global issue that local politicians and citizens sometimes cannot see that there are things that can be done at a local level that are important steps in the right direction’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2009: 15). She cited many examples of actors that had an obvious motivation to self-organise:

Better health is achieved by members of a household who bike to work rather than driving. Expenditures on heating and electricity may be reduced when investments are made in better construction of buildings, reconstruction of existing buildings, installation of solar panels, and many other efforts that families as well as private firms can make that pay off in the long run.

Essentially, she argued that scholars (and practitioners) had become too fixated with the resolution of collective action dilemmas at the international level, when there might be multiple externalities and collective action dilemmas to be addressed at many levels. The descriptive implication of Proposition 1 is therefore important: analysts should adopt an actor-centred focus and examine what motivates actors to self-organise across the entire governance landscape.

The explanatory implication of Proposition 1 is equally pertinent: analysts should ‘get out into the field’ and study how governance is actually enacted in practice (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2011: 17; Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 243). In Ostrom’s (Reference Ostrom2009: 14) words: ‘[i]f there are benefits at multiple scales, as well as costs at these scales … the theory of collective action … needs to take these into account.’ Regarding the emergence of polycentric governance, Proposition 1 encourages analysts to be open-minded about the role of states. Are states deliberately pursuing polycentric governance by delegating responsibility down and out to other actors (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011: 67) and engaging in forms of orchestration? Or is climate governance genuinely emerging from the bottom up, as non-state and subnational actors fill the cracks in state-fashioned global policy?

Finally, Proposition 1 carries some important normative-prescriptive implications. First, local communities possess the skills, (local) knowledge and capacity to overcome many challenges (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 246), and hence problems should be addressed as close as possible to them (i.e. following the principle of subsidiarity; see Tarko, Reference Tarko2017: 56). Second, community decision-making must follow from an open and democratic process adhering to the rule of law (note the link here with Proposition 5 – overarching rules). Third, it should not be automatically assumed that all actors are necessarily dealing with one problem at a time – hence the importance of understanding what has come to be known as the ‘co-benefits’ of mitigation (e.g. Stewart, Oppenheimer and Rudyk, Reference Stewart, Oppenheimer and Rudyk2013). Fourth, governors should not lapse into binary thinking, as this tends to produce panaceas and other naïve prescriptions (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2007). For example, not all coordination problems will necessarily respond positively to polycentric interventions; governance should be about matching problems with the relevant inter-organisational arrangements at the ‘right level’ (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 242).

Proposition 2 – Mutual Adjustment Constituent units are likely to spontaneously develop collaborations with one another, producing more trusting interrelationships.

In a polycentric system, once the constituent units have emerged, they will naturally interact. Vincent Ostrom (Reference Ostrom and McGinnis.1999: 57) even defined polycentric systems in such terms: they have ‘many elements [which] are capable of making mutual adjustments for ordering their relationships with one another within a general system of rules where each element acts with independence of other elements’ (emphasis added). This explains why polycentric systems are often likened to complex adaptive systems (Tarko, Reference Tarko2017: 58): mutual adjustment is what allows them to adapt to changing external conditions, their actions in turn feeding back on other actors. It is understood to mean the way in which units in a polycentric system communicate with one another; the extent to which mutual adjustment is actually capable of bridging significant differences amongst the units remains an important but unresolved matter (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016: 9). The notion of mutual adjustment carries strong echoes of what Lindblom (Reference Lindblom1959) referred to as partisan mutual adjustment – a concept he also developed from work conducted in the relatively polycentric political system of the United States.2

Proposition 2 has important implications for how governance is described: attempts to comprehend a particular governance landscape should identify all the constituent units and explore their interconnections.

From an explanatory perspective it implies that researchers should seek to understand the boundaries of, and the interactions between, their constituent parts (Tarko, Reference Tarko2017: 64), rather than assume that a particular level or actor is dominant. This speaks to the ongoing debate among polycentric thinkers about the tensions and frictions between a system’s mono- and polycentric tendencies (Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 248), as well as between it and cognate systems (which may exhibit similar or very different degrees of polycentricity). The polycentric governance literature is intensely interested in how mutual adjustment comes about. Is it through autonomous couplings between units? If so, do they spontaneously emerge or are they guided by ‘higher-level’ authorities? Is mutual adjustment mostly a process of voluntary learning, or is there a degree of competition in some cases, and can it possibly even border on coercion?

Finally, the normative-prescriptive implication is that governors should seek to liberate the ‘error-correcting’ capacity inherent in all mutually adjusting polycentric systems (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016: 9), which also connects to the strong presumption in favour of local action (subsidiarity).

Proposition 3 – Experimentation The willingness and capacity to experiment is likely to facilitate governance innovation and learning about what works.

Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2010a: 556) argued that one of the main benefits of polycentric governance is that it allows – even encourages – actors to experiment with different approaches. Over time, common methods for assessing costs and benefits can be established between actors operating in different domains, so that experiments in one setting actively inform experiments in other domains. The presumed importance of learning is something that polycentric theory shares with many other literatures, including those addressing pluralism, localisation and decentralisation. In Lindblom’s (Reference Lindblom1959) theory of partisan mutual adjustment, policymakers were also assumed to move forward cautiously on the basis of tinkering and experimenting, rather than overarching plans and strategies. Crucially, if one intervention fails, the broader system remains robust and better able to respond in the future, having learned from the experience (Cole, Reference Cole2015).

Proposition 3 has several important implications. Descriptively, it implies that analysts should seek to understand what – if any – experiments are taking place and how they function. Some argue that ‘a polycentric system of climate policies necessarily entails a greater number of discrete policy experiments’ (Cole, Reference Cole2015: 115, emphasis added). By this, they mean that in a polycentric system, multiple approaches to problems are tried out at the same time. A polycentric governance system is thus a quasi-experimental system, which – through its internal diversity – offers the opportunity to see what works and what does not. In a descriptive sense, therefore, the emphasis is on the degree to which such a diversity of approaches really exists, the degree to which experiments are grounded in an action theory which is tested and evaluated, and the extent to which the knowledge from experimentation flows freely around and through a system (Huitema et al., Reference van Asselt, Huitema, Jordan, Turnheim, Kivimaa and Berkhout.2018).

In explanatory terms, however, a crucial issue lies underneath: the term experiment is in large part socially constructed; it can be interpreted in various ways. To some, an experiment is anything outside the ordinary (i.e. trying something new), whereas for others, experiments should always include the wish to test the intervention rationale that underpins a particular governance intervention. And for many, the term experiment denotes an explicit comparison of the outcome against the status quo prior to the intervention and against the outcomes in a control group where no interventions were made. It would seem that at present, polycentric governance theorists are content to regard any diversity of approaches as an experiment, but conceptual models of how this subsequently translates into more or less learning and innovation are scarce. In the emerging literature on experimentation in climate governance (see e.g. McFadgen and Huitema, Reference McFadgen and Huitema2017), it is becoming clear that: experimentation may stifle innovation when it is used as a tactic to delay action; experimentation may be selective (it is difficult to conduct more than one experiment at a time); and the evaluation of experiments is a highly political process, if only because those initiating them often have a stake in their success. In other words, experimental insights can all too easily be manipulated or even ignored (see also Chapter 6).

Finally, the normative-prescriptive implication is that governors should actively encourage decentralised experimentation to determine ‘what works best’ in particular contexts (Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017: 55). Here one encounters another interesting tension in polycentric governance thinking, because the statement ‘what works best’ seems to be based on the belief that agreement can be reached on what is best. In practice, the criterion for what is ‘best’ might differ per community, which may mean that the results of experiments are interpreted in very different ways, and that mutual learning processes go in different directions (leading to greater diversity and a lower degree of polycentricity, facilitated by conflicting evaluative criteria, etc.). As yet, there is little explicit discussion in the literature on how far this jars with the notion of mutual adjustment (Proposition 2).

Proposition 4 – The Importance of Trust Trust is likely to build up more quickly when units can self-organise, thus increasing collective ambitions.

In international political theory, states are assumed to be engaged in a struggle to adopt binding emission reductions in a context of great uncertainty, each having highly differentiated response capacities and responsibilities. In general, the level of trust is assumed to be low (hence repeated references to the risk of free-riding). In seeking to reframe the debate, Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2009: 11) argued that at a more local level, things may work out rather differently. Trust may be in greater supply, born of (among other things) the greater likelihood of face-to-face interactions between actors (Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017: 57). When trust is more plentiful, polycentric thinkers argue that the standard assumption within rational choice theory – that actors maximise their short-term interests – may not apply (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom1998).

The descriptive implication of Proposition 4 is that analysts should expand their accounts of reality to encompass the relationships between a wider universe of actors operating in and across different levels and units of governance, and that they should focus on processes of trust-building at all of these levels.

From an explanatory perspective, the key implication is that researchers should aim to understand whether and how trust varies within and between different units and domains (Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017: 57). Another key question is under what conditions is trust more likely to grow? In general, trust emerges out of repeated interactions and, in particular, when promises are repeatedly fulfilled. Cole (Reference Cole2015: 117) suggests that it grows fast when experiments (see Proposition 3) deliver concentrated benefits at a local level (Cole, Reference Cole2015: 117). But other parts of the polycentric literature point to the importance of either direct participation (see Proposition 1) or information sharing, through common systems of monitoring (see Proposition 5) (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010a: 554). Polycentric theorists are undoubtedly eager to understand precisely which activities are being monitored by whom and for what purpose (Schoenefeld and Jordan, Reference Schoenefeld and Jordan2017). They claim that if the purpose of experimenting is to promote longer-term learning, then trust is more likely to be engendered not by monitoring, but by more participatory forms of ex-post evaluation. If that is the case, the choice of which body performs the evaluation (and hence sets the evaluative criteria) becomes critical (Hildén, Jordan and Rayner, Reference Hildén, Jordan and Rayner2014).

Finally, the normative-prescriptive implication of Proposition 4 is that various actions should be taken to encourage trust, including local-level working (see Proposition 1), experimentation (Proposition 3) and monitoring and evaluation ‘at all levels’ (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2009: 39). Article 13 of the Paris Agreement is explicit in this respect. However, with global problems such as climate change, it is less obvious who or what should perform these functions.

Proposition 5 – Overarching Rules Local initiatives are likely to work best when they are bound by a set of overarching rules that enshrine the goals to be achieved and/or allow conflicts to be resolved.

References to a set of overarching rules are found in almost all definitions of polycentric governance (e.g. Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 237). They are assumed to provide a means to settle disputes and reduce the level of discord between units to a manageable level. Their primary role is to protect diversity (Proposition 1) and facilitate mutual adjustment (Proposition 2). However, their exact form and function is something on which theorists cannot yet agree (see Aligica and Tarko, Reference Aligica and Tarko2012: 254ff.). Do they, for example, take the form of informal norms and values within societies – things that ensure a basic level of pluralism? Or are they formal rules and state organisations such as courts that arbitrate when disputes occur, or agencies that engage in monitoring? In principle, the former interpretation seems compatible with the other four propositions, and the latter appears, somewhat counterintuitively, to assume a higher degree of monocentricity than seems possible in purely polycentric systems (McGinnis, Reference McGinnis2016: 11; but see Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2014).

The implications of Proposition 5 are therefore potentially far-reaching. Descriptively, it suggests that analysts should try to account for the role played by different types of rules. Second, they should be alive to the possibility that as well as maintaining order, rules may represent ‘an opportunity structure’ through which actors seek to effect change (Tosun and Schoenefeld, Reference Tosun and Schoenefeld2017). In other words, the overarching rules may be sources of change as well as continuity (i.e. not be completely fixed).

In an explanatory sense, it provokes analysts to consider how to study rules empirically. For example, where do they derive from and what form do they take? Do they arise from intergovernmental bargaining, or do they emerge organically from activities at lower levels? Do they focus on or enable greater accountability or transparency? Oberthür (Reference Oberthür2016: 82) argues that ‘[t]he Paris Agreement … provides some overarching guidance to the overall governance framework.’ However, this says nothing about causality – does the UNFCCC process steer local initiatives, or vice versa? In practice, much is likely to depend on whether the rules are perceived as capable of holding powerful actors to account (Huitema et al., Reference Huitema, Jordan and Massey2011). If the overarching rules are not deemed legitimate and actors step back from them (as the United States did in 2001 under President George W. Bush, and has done again under President Donald Trump), they may not be particularly ‘overarching’. Also, questions could be asked about the connections between the existence of conflict resolution mechanisms on the one hand and trust-building mechanisms on the other (Proposition 4), the degree to which experimentation (Proposition 3) (and thus deviation) is still possible under overarching rules (especially when these are quite rigid) and the degree to which self-organisation (Proposition 1) aligns with the upholding of fundamental democratic principles.

Finally, in a prescriptive sense, Proposition 5 provokes analysts and practitioners to think about the most desirable rules, norms and organisations – a potential tricky task given that they may blend elements of monocentricity and polycentricity.

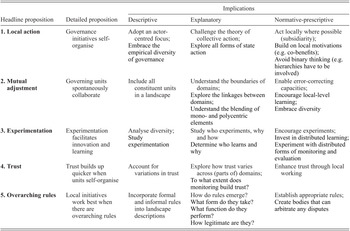

Table 1.2 summarises the five propositions and outlines their most significant implications for analysts and practitioners.

Table 1.2 Polycentric governance propositions and their implications

1.4 Plan of this Book

We know that the climate governance landscape is in a state of great flux. Practitioners are intuitively aware that it encompasses many more actors, modes and levels of governance than it did even a decade ago. Simply describing the rapidly evolving landscape constitutes a significant research challenge in itself. In the late 2000s, Ostrom sought to move towards a deeper and more holistic understanding by proposing that analysts study it from a polycentric perspective. Since her death, polycentric thinking has gained a lot more traction within the climate governance community, but for many scholars its embedded assumptions and core propositions are not very well known. For those who have not encountered her work on climate change, polycentric governance is likely to be regarded as lying somewhere outside the mainstream in governance research.3 We have therefore devoted considerable space in this chapter to better specifying the theoretical claims of polycentric thinkers, by unpacking a number of definitions of polycentric governance and pinpointing five key propositions that emerge from them. We then explored the implications of each for the ways in which governance can be described, explained and prescribed.

In doing so, we have confirmed that polycentric governance offers a distinctly different take on contemporary climate governance. In its framing, it is very different to the standard, international policy approach which reifies interstate diplomacy. It is also distinct from related concepts such as regime complexity, institutional fragmentation and experimentalist governance, for which the main point of reference remains international actors (van Asselt, Huitema and Jordan, Reference van Asselt, Huitema, Jordan, Turnheim, Kivimaa and Berkhout.2018). It shares some similarities with certain (so-called Type II) variants of multilevel governance theory and political federalism (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2011: 15), although unlike them, it is more directly concerned with the role of non-governmental units and/or situations in which jurisdictions overlap. It has most in common with theories of networked governance, with which it shares a concern with how and why centralised and decentralised forms of coordination emerge and find some coexistence (McGinnis and Ostrom, Reference McGinnis and Ostrom2011: 15).

The aim of this book is to explore what is to be gained by thinking about climate governance as an evolving polycentric system. It does so by bringing together some of the world’s leading experts on climate governance, who are very well placed to connect the relevant strands of conceptual and empirical work and view it through the prism of polycentric governance. Together, they address four main questions. First, how polycentric is climate governance post-Paris (both in its totality – as a broad system – and in particular domains)? Answering this question necessitates a better understanding of how specific domains of governing approximate the essential definition outlined by Elinor Ostrom. It also necessitates much greater critical reflection on the relationship within and between different domains. These topics are mainly addressed in Part II of this book.

Second, when, how and why has climate governance become more polycentric, and how do polycentric systems function? Here, the chapter authors evaluate the validity of the five core propositions. This task is mostly addressed by the chapters in Part III.

Third, what are the implications of greater polycentricity for the governance of pertinent and theoretically substantive challenges such as rapid decarbonisation, the transfer of climate change mitigation technologies to poorer countries and adaptation to climate impacts, as well as for the accomplishment of broader, system-wide functions (e.g. innovation, equity, justice, legitimacy and accountability)? This question is directly addressed by the authors of the chapters in Part IV.

Finally, what in summary is the most salient purpose of the emerging framework of polycentric governance? Ostrom (Reference Ostrom2010a) was confident that it could serve three important purposes: describing, explaining and prescribing. In practice, these purposes have become somewhat confused in the minds of those studying polycentric governance. In Chapter 20, we critically reflect on how well the chapters address the four questions and consider the promise and potential limits of a polycentric perspective.