Dorothea Mackellar’s poem ‘My Country’, first published in London in 1908 by its homesick author, recalls life in rural Australia. Born into a wealthy Sydney family in 1885, Mackellar’s Australian-born parents owned a number of large rural properties.Footnote 2 The poem opens by suggesting that ‘the love of field and coppice’ and of ‘ordered woods and gardens’ runs in the veins of a British audience. Mackellar regrets Australia’s ‘ring-barked forests’ but celebrates ‘the wide brown land’ and declares love for the ‘sunburnt country’. ‘Droughts and flooding rains’ are the essence of the water management challenges across Australia, including its ever-growing cities. When Mackellar wrote ‘My Country’, 55 per cent of Australians lived in cities and towns, many of which were vulnerable to extremes of too little water, or too much. The five mainland state capitals alone were home to one in three Australians; currently the figure is two in three.

How has water shaped the largest Australian cities? What are the historical drivers that produced today’s urban water systems, and how have these systems impacted on human and ecological welfare? This book aims to reveal not only why our urban water systems developed as they did but also the many ways in which they have shaped city growth and suburban development.

There is much to learn from the stories of how both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians have learned to live with climate variability over a range of timescales. Mackellar’s poem makes no mention of Indigenous inhabitants or landscapes, but it is important to recognise that the places that are now Australia’s five largest metropolitan capitals were deeply known, managed, and loved for tens of thousands of years before the present, and that the Aboriginal peoples of those places have – remarkably, given the violent disruption of colonisation – maintained connection with and knowledge of those places. In telling of Aboriginal relationships with water in these locations, our approach as non-Indigenous historians is to collate narratives respectfully from Indigenous and non-Indigenous accounts published in the public domain, whether in the form of oral testimony or written word. Where possible, we follow the guidance of Palyku legal scholar Ambelin Kwaymullina by seeking to privilege Indigenous voices and engage with works produced by Indigenous people in ethical partnerships with non-Indigenous people.Footnote 3 We recognise that while there is a diversity of Indigenous views, ‘Aboriginal stories, however expressed or embodied, hold power, spirit and agency’. Moreover, ‘Knowledge can never be separated from the diverse Countries that shaped the ancient epistemologies of Aboriginal people, and the many voices of Country speak through the embodiment of story into text, object, symbol or design.’Footnote 4 We pay our respects to the First Nations people and the land on which their ancestors lived for millennia. We hope this current work reflects, in some small part, their generations of custodianship and a perspective that will endure and guide future generations.

In 2015, the World Economic Forum declared water crises to be the biggest risk facing the planet.Footnote 5 Yet, in Australia, there has been surprisingly little reflection on how the past has shaped our urban water systems, or how this knowledge might inform present solutions to water management problems. There is an extensive literature on the history of Australian urbanisation, including studies of individual cities and histories of particular suburbs or local government areas.Footnote 6 The issue of how governments overcame the challenge of providing water to urban residents is implicit in much of this literature. Yet, these works provide no coherent understanding of how water availability and scarcity have shaped urban structures and environments, neighbourhoods’ social experiences, or individual living standards through different periods of population growth, economic and land use changes, flood, and drought. The historiography of water in Australia has largely focused on the rural sector and irrigation schemes.Footnote 7 Many book-length studies of urban water have been commissioned by the statutory authorities that built the dams, reservoirs, pipelines, and sewage treatment plants.Footnote 8 Very little has been written on how the majority of Australians, the capital city dwellers, have shaped and been shaped by one of the nation’s most defining characteristics – its relationship to fresh water.

Cities in a Sunburnt Country is the first comparative study of the provision, use, and social impact of water and water infrastructure in Australia’s five largest cities – the nation’s only cities to have exceeded a population of 1 million. Large-scale water supply and sewerage infrastructure has underpinned the growth of large cities, with intended and unintended consequences. Beginning with the First Australians, the book sketches Indigenous understandings and approaches to water and Country, before turning to the early colonial development of small-scale water sources and then the domestication of water with large-scale water supply and sewerage infrastructure. The book concludes in the twenty-first century, when prolonged drought and the spectre of anthropogenic climate change raised questions as to the sustainability of long-standing assumptions and strategies for urban water management.

As Australia’s cities continue to grow in the face of changing climates, water has been thrust to the forefront of national conversations about sustainability and urban futures. Fresh water resources within easy reach have already been harnessed, often to their maximum capacity, attaching a mounting sense of urgency to these discussions. An understanding of why complex water cultures and infrastructures exist in their current forms can enable a more historically informed and equitable approach to urban water provision and management. While new approaches and technologies will be required to face future challenges, and there is something deeply attractive about models of well-designed water-sensitive cities, plans to dramatically alter urban water systems must not only work with the present urban fabric but also rely on public support. Examining the development of urban water supply can help citizens to reflect upon what they value about present systems and inspire confidence to change without losing what counts most. Policymakers, too, can consider how past changes have occurred, in order to inform their own approaches to developing just, equitable, and sustainable strategies for managing and accommodating water in Australian cities.

At a time when water systems of large cities worldwide are under pressure from environmental change and population growth, historical knowledge of the provision, use, and cultures of water is critical. Comparatively rapid changes to water supplies, river flows, the frequency of floods and droughts, and rising sea levels mean the need for cities to respond effectively to the challenge of water supply and sanitation is stronger than ever. Every metropolis produces its own set of water management problems that must be addressed in the context of particular knowledges, cultures, technologies, and levels of economic development for the city to continue to function. Some decisions, once made, cannot easily be undone – and may have ongoing consequences for later generations. The challenge to produce effective water management strategies that foster more sustainable, resilient, productive, liveable, and equitable cities is an example of a ‘wicked’ problem that defies simple solution.

This book was written by seven researchers with a shared mission of seeking to contribute to the creation of more resilient and sustainable water systems through an enhanced understanding of water history. Its genesis lies in an invitation to join the Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) for Water Sensitive Cities, formed in 2012 to bring together researchers from disciplines and sub-disciplines across social and biophysical sciences and humanities. This interdisciplinary forum allowed us to share ideas and approaches, with dialogue formalised through works of synthesis, including a summary CRC report,Footnote 9 as well as a special issue of Journal of Urban History (‘Water and the making of Californian and Australian cities’).Footnote 10 In 2015, we secured funding from the Australian Research Council to produce the first longitudinal, multi-city comparative historical study of how and why water has been provided to Australian cities, and how it has transformed them. One of the principal aims of the new project was to integrate cultural, economic, and environmental histories. We felt that this was an essential precondition to two of the other project aims: producing new knowledge that might help to improve the effectiveness, equity, and sustainability of Australian urban water policy; and producing water stories that engage the public through history and help us imagine alternatives. In addition to this book, the project also produced a virtual exhibition at the Rachel Carson CenterFootnote 11 and a special issue of Australian Historical Studies (‘Ripple effects: Urban water in Australian History’).Footnote 12

As a ‘wicked’ problem, the achievement of sustainable water systems requires bridging disciplinary divides to deliver knowledge that can inform appropriate resource use and policy action. This necessity is increasingly recognised in the broadening field of urban water management, which has extended beyond engineers and sanitarians to include economists and more recently the insights of the humanities and social sciences, as well as Indigenous peoples. Our team also brings together diverse expertise and perspectives. As individual scholars, we have published in environmental history, economic history, urban history, planning history, and public administration. Some of us have published in more than one of those fields. As historians from different sub-disciplines working in conversation across our various areas of expertise, we are able to ask new questions, identify the complex causes of past problems, unearth a wide range of relevant stories, and suggest diverse lessons for the future. Accordingly, rather than an anthology of chapters from individual authors – reflecting author sub-disciplinary perspectives – each chapter has been co-written. Each is the product of constructive dialogue and co-creation between researchers who have developed and drawn on both disciplinary expertise and interdisciplinary orientation.

Australia is the driest inhabited continent, with a desert centre and few large river systems. Located on coastal fringes and separated by long distances, the five cities are marked by climatic diversity. Adelaide and Perth’s Mediterranean climates are comparable to those of the Mediterranean region itself, and other regions where a similar climate prevails, such as southern California, south-central Chile, and South Africa’s Western Cape. Such climates are confined to relatively narrow coastal fringes, as mountain ranges block the movement of oceanic weather fronts, creating rain shadow effects. In nearby mountains and hills where rainfall is higher, river systems and valleys in nearby mountains provide sites for urban water storages to supply cities on the coastal plains.

Perth’s long-term average (since 1876) annual rainfall of 838 mm is much higher than that of Adelaide, which averages 533 mm.Footnote 13 Perth, however, has experienced a drying trend from the last quarter of the twentieth century. Average rainfall has been declining since 1971, and the figure from 1994 to 2015 was 13 per cent below the historic average. Very little rain falls in Perth in summer, the sandy soil does not retain water, and evaporation rates are high. In Adelaide, the average evaporation rate exceeds rainfall every month except in late autumn and winter. That city’s water supply is critically dependant on the River Murray and the River Murray basin – a semi-arid region that has the lowest run-off of any large river system in the world.Footnote 14 The flow of water through the river system exhibits a wider range of variability than almost any other of all the world’s major river systems.

Melbourne’s climate is more temperate and oceanic, with changeable weather conditions resulting from the influence of hot inland winds and air masses and the cool Southern Ocean. Rainfall averages 521 mm per annum, distributed more evenly over the year than in Perth and Adelaide. The more northerly east coast capitals, Sydney and Brisbane, have temperate and sub-tropical climates with much higher average rainfall than the three southerly cities (1175 mm per annum in Sydney, 1149 mm in Brisbane), although both are also vulnerable to periodic, extended drought and significant variation in average rainfall across the urban area. Sydney has a temperate climate of warm, sometimes hot summers and mild winters, with temperature variations moderated by proximity to the Pacific. Brisbane’s climate is sub-tropical, with hot, humid summers, in which thunderstorms are common, and dry, moderately warm winters.

The east coast capitals are subject to the effects of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), alternating periods of seven to ten years of dry and wetter conditions. At longer, unpredictable intervals of twenty to thirty years, they may also be impacted by Pacific Decadal Oscillation patterns of warming and cooling of the ocean surface, which act as ‘throttle and brake’ for shorter ENSO cycles of drought and flooding rains.Footnote 15 Perth’s rainfall is also affected by variability in sea surface temperatures associated with the Indian Ocean Dipole.

Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth, the north-western suburbs of Sydney, and parts of Adelaide are built on floodplains. Melbourne’s Yarra River drains a catchment of over 5000 square kilometres south of the Great Dividing Range, a complex of mountains and uplands extending from western Victoria to northern Queensland that separates coastal areas and inland grasslands. The city of Melbourne is located on flat, naturally swampy ground. Major floods occurred in Melbourne in 1839, 1863, 1891, and 1934. At around 13,500 square kilometres, the Brisbane River catchment, also in the Great Dividing Range, is larger than the Yarra catchment and subject to heavier rainfall. Brisbane’s inundation in 1893 was the result of three flood events within one fortnight, the 1974 flood was caused by rainfall from decaying tropical cyclones, and the catastrophic flood of 2011 was associated with strong La Niña rain events.Footnote 16 Perth’s Swan River and its tributaries are part of a very large river system, the Avon River, which has a catchment area of almost 120,000 square kilometres. Perth’s most extensive flooding was in 1862, 1872, and 1926; the city experienced eleven floods with an average recurrence interval of ten years between 1910 and 1983.Footnote 17

For all its size, Australia has a small population relative to comparable continents such as North America. At the point of British invasion and subsequent colonisation in 1788, the Indigenous population was an estimated 800,000, spread out in settings ranging from desert to sub-tropical coastal rainforest.Footnote 18 None of the Indigenous camps and settlements had large populations in particular localities, other than the much more closely settled Torres Strait Islands. However, all of the sites of the five settler cities were home to thriving Indigenous groups. These groups sustained themselves over millennia with the water available in their regions. They achieved this through detailed, intergenerational knowledge of Country and its patterns of water movement through and under the land, as well as respect for water as a living entity: water was and is held central to everyday material and spiritual life. The importance of water, and its power over life and death, is woven into legends that capture both the moral dimensions of water and its capacity to shape landscape over millennia. The changing seasonal abundance of water guided the location of campsites and seasonal patterns of movement between them: mobility was a key element of the groups’ relationships with water. Indigenous water cultures vary, yet they share a common approach to water, based on understanding and respect. By contrast, settler approaches have usually been based on control, though recent consideration of water-sensitive urban design reflects a turn towards knowledge and adaptation.

European colonisers always sought out settlement prospects with ready fresh water, not just for drinking but also market gardening, given the necessity to be self-sufficient in fresh food as reliance on the irregular supply of dried foodstuffs from Britain was untenable. All early settlements had ocean or river access, with farming lands near to watercourses. Early industries included whaling and timber, with wool becoming the dominant export from the 1830s. Most long-distance movement of goods and people was by ship, whether around the continent itself or to and from Britain. Two of the five mainland capital cities, Sydney and Brisbane, were convict settlements; Perth received convicts from 1850 to 1868; Melbourne and Adelaide were free settler colonies. The prosperity of the wool industry, and the discovery of gold in Victoria and New South Wales in the 1850s, further integrated Melbourne and Sydney into a burgeoning world economy. By the end of the nineteenth century, both had close to half a million inhabitants, making them the 46th and 47th most populous cities in the world.Footnote 19 This extraordinary urban growth, in a country with a population at that time of a little less than 4 million, represents a pattern that continues to the present day (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Population of the five cities (thousands), 1851–2021

| Census date | Sydney | Brisbane | Perth | Melbourne | Adelaide |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1851 | 54 | 3 | 8 | 29 | 18 |

| 1901 | 496 | 119 | 61 | 478 | 141 |

| 1947 | 1484 | 402 | 273 | 1226 | 382 |

| 1976 | 3144 | 1058 | 846 | 2764 | 940 |

| 2020 | 5367 | 2561 | 2125 | 5159 | 1377 |

The British crown claimed all of the Australian continent, including land and water, regarding the continent as ‘terra nullius’ (nobody’s land). This fiction was only overturned with the Mabo judgement in 1992, which acknowledged Native Title. British governors, as royal representatives, were installed in every colony (and continue to perform constitutional and ceremonial functions). In 1900, the British parliament gave permission for the Australian colonies to federate as the ‘Commonwealth of Australia’, with the colonies becoming states the following year. ‘Crown land’ still underpins land ownership in Australia, while the Crown owns the continent’s subterranean resources, whether water or mineral. State governments oversee land sales, levying stamp duty on all land transfers. The primary landowners in every Australian state remain the state governments, which retain the right to appropriate private property for ‘public goods’, from freeways to dams, pipelines, and reservoirs.

Land grants and land sales were overseen by colonial governors and later Departments of Lands. Properties were subdivided for residential, commercial, and industrial purposes, while river and water reserves provided respite from the relentless march of privately owned land, enabling Aboriginal people to make semi-permanent homes. The most sought-after residential sites tended to look out over waterways, whether rivers, harbours, or later beaches; the wealthy preferred elevated sites, especially in flood-prone cities. Industries, especially those which needed plentiful water or ready waste disposal, also sought river sites; consequently, tanneries, boat builders, brewers, flour mills, and paint manufactures were established along waterways. Later, the need for water supply prompted construction of coal-based gas plants and later electricity power stations near waterways.

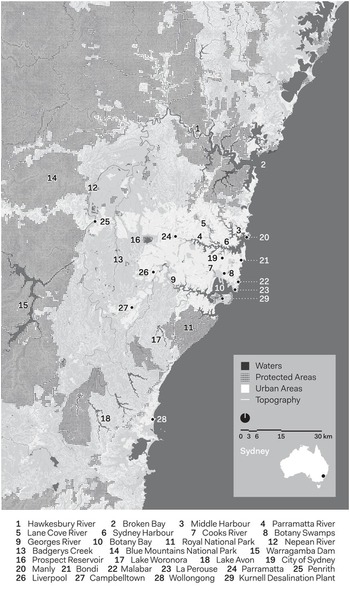

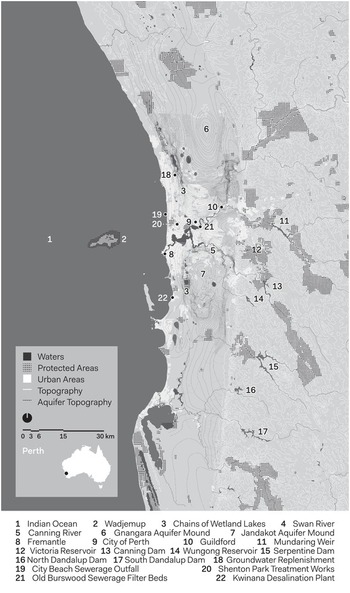

Maps of the five cities in 2021, created by environmental designer Daniel Jan Martin and drawn to the same scale, show their oceanic settings, along with rivers, bays, and harbours. The current urban footprint is indicated in white shading, while protected areas are indicated by cross-hatched shading. These areas include national parks and nature reserves, preserved by state governments in perpetuity. Sydney is the only city of the five where protected areas serve as a key barrier to future urban growth. Melbourne has an almost unlimited hinterland for future urban development. Adelaide has partially regulated its urban sprawl, limiting development in the hill catchment areas to the east while allowing an ever-increasing north–south footprint. New suburban development in Perth and Brisbane heads to the north and south along the coast as well as moving inland along major transport corridors, following freeway systems.

Sydney (Map 1.1) developed on a semi-circular site, abutting the Pacific Ocean. It has substantial bays and river systems to its north (Broken Bay and the Hawkesbury River), west (the Nepean River), and south (Botany Bay and the Georges River). All three rivers flood after heavy rain, whereas the much deeper harbour, without riverine choke points, is not subject to flooding.

Map 1.1. Sydney.

The initial British invasion force, predominantly composed of naval personnel and convicts, made their first settlement at Port Jackson (now Sydney Harbour), close to what is today Sydney’s Central Business District, which offered a ready supply of fresh water. The Eora nation, traditional owners comprising a number of clans with their own territories, were decimated by introduced disease and frontier violence. The survivors’ lifeways were devastated as successive governors, having claimed the continent for the Crown, handed out land grants to colonists for residential development and farms.

Much of the early settlement took place to the west and north-west of the town centre, with the valleys of the Parramatta, Nepean, and Hawkesbury Rivers all sought after for farming land. In the latter decades of the nineteenth century, suburban development followed train and tram routes. Reservoirs and water towers were built at high points around the growing metropolis. The water supply was augmented by five dams built in bushland to the south of the city between 1907 and 1941, with that supply almost quadrupled by the Warragamba Dam, which opened in 1960. The creation of large national parks, Ku-ring-gai Chase to the north, National Park to the south, and the Blue Mountains to the west, curtailed suburban development, allowing Sydney more guaranteed green space and better-quality water catchment areas than any other Australian capital city. Sydney is often said to be blessed by its spectacular harbour and riverine topography, which made it feasible to build so many dams, also allowing cheap and easy solutions to the disposal of stormwater, sewage, and industrial waste, which created major pollution problems in the latter decades of the twentieth century. Public outcry eventually pressured the extension of the city’s ocean outfall sewers further into the sea.

Between 1901 and 2021, Sydney’s population grew tenfold, now standing at 5 million. Mass car ownership from the late 1950s saw suburban developments take over most remaining farming land. Since the 1970s, about one-third of all new housing has been provided by town houses and apartment blocks, at much higher densities than the traditional house and garden.

Brisbane developed around the Brisbane River, approximately 25 km upstream from its mouth in Moreton Bay (Map 1.2). The Brisbane River is 344 km long and within its 13,500 square kilometre catchment lies the sub-catchments of three rivers – Stanley, Brisbane, and Bremer Rivers – and twenty-two creeks, the largest of which is Lockyer Creek. The river is characterised by its meander, a propensity to flood, and its variable flow rate, which reflects the region’s sub-tropical climate and high average rainfall.Footnote 20

Map 1.2. Brisbane.

Meanjin, the lands of the Turrbal and Jagera peoples were occupied by the British in 1823 and named Brisbane. The British established the Moreton Bay penal colony in 1824 on the banks of Maiwar (the Turrbal name for the Brisbane River) and the current site of Brisbane’s Central Business District, where the river offered a water supply and effluent dump. The penal colony closed in 1839 and the town opened for free settlement in 1842 as a part of the colony of New South Wales, gaining status as the colony of Queensland in 1859. Providing potable water was an early concern, solved by the construction of water tanks and the Enoggera Dam in 1866. Ongoing tension between managing water supply and flood mitigation culminated in the completion of two dual-purpose dams, Somerset Dam in 1959 and Wivenhoe Dam in 1984. Wivenhoe Dam provides most of Brisbane’s water supply and, reflecting the region’s variable climate, holds 2000 times the city’s daily water supply when at full supply level.

In 1901, Brisbane’s metropolitan area had a population of 119,000; in 2021, the number is fast approaching 2.5 million, making Brisbane Australia’s third most populous city. The single house and garden on a 400 square metre block remain the dominant housing stock. The only capital city to adopt a metropolitan-wide council (in 1925), Brisbane spilled over into neighbouring local government areas in the 1970s. Since the 1990s, the delineation of the separate settlements on the Sunshine Coast, Gold Coast, Ipswich, and Brisbane has blurred, effectively creating a 200 km-long city.Footnote 21 Accordingly, water supply is managed as part of a complex grid that links dams, recycled water supply, and the Gold Coast desalination plant. With south-east Queensland’s population growing by 80,000 people per year since 1981, the region’s current population of 3.5 million is expected to reach 4.4 million by 2031 and 5.5 million by 2051.

The Perth metropolitan area is situated largely on a coastal plain that varies from around 23 km to 34 km in width, hemmed in by the hills of the Darling Scarp to the east and the Indian Ocean to the west (Map 1.3). Perth developed from Indigenous settlements established on the banks of the Derbarl Yerrigan, or what white settlers called the Swan River. While there was conflict with the Whadjuk Noongar almost from the beginning of colonisation, Aboriginal people have remained in and around Perth to the present day.

Map 1.3. Perth.

The colony’s natural capacity to support European-style agriculture did not live up to the glowing reports of Captain James Stirling and botanist Charles Frazer, who reconnoitred the area in 1827. Much of the Swan Coastal Plain is characterised by sands with low levels of the nutrients required by European crops and livestock. The winters were cool and wet but the summers hot and dry, often with little significant rainfall falling over the summer months. With insufficient labour and no experience of farming in such an environment, the colony struggled until the introduction of British convicts in 1850. Modest growth followed between the port settlement at Fremantle, administrative centre in Perth, and the agricultural service centre of Guildford at the confluence of the Swan and Helena Rivers. At first connected by the Swan River in 1883, when the settler population numbered around 8500, these nodes were also linked by Perth’s first suburban railway. The forested hills to the east of Perth seemed the obvious location for water catchment and storage that could be gravity-fed to the city. The first such dam, Victoria Reservoir, was completed in 1891.

With the discovery in 1892–93 of large gold deposits at Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie, around 500 km east of Perth, the settler population quadrupled in a decade, with low-density suburban development extending around the railway line connecting Fremantle, Perth, and Guildford. The wealth generated by gold supported increased investment in public infrastructure, including a mains sewerage scheme to which the first homes were connected in 1911. After a short-lived experiment with treatment of sewage and disposal into the Swan River, which added to the effluent from noxious industries, Perth’s first ocean outfall was constructed in 1926. But the low-density, distributed nature of urban development in a place with complex topography made centralised sewerage expensive, and pan toilets and increasingly septic tanks remained important means of waste disposal.

The boom of the 1960s and 1970s also saw increasing exploitation of Perth’s groundwater resources, first to supplement the city’s drinking water supply and then by householders sinking bores for garden watering. Further dams were built in the Darling Scarp, but following the decline in average rainfall in south-western Australia from the 1970s, the share of dam water in the city’s drinking water fell. As population surged again in the 2000s in the wake of another mining boom, the city’s orientation along around 80 km of coastline provided ready access to abundant seawater. The first desalination plant was commissioned at Kwinana in 2006, with desalinated seawater pumped to the hill reservoirs for storage and distribution; by 2019–20, desalinated seawater made up 43 per cent of the water supply for Perth’s 2 million people. The city’s aquifers also provided capacity for groundwater replenishment using treated wastewater, which commenced on a trial basis in 2010 and on a more permanent basis in 2017.

Melbourne’s location at the top of Port Phillip Bay positioned it at the centre of the colony (later state) of Victoria, with a hinterland that included the major goldfields of the 1850s, rich pastoral land to the west, and the grasslands beyond the Great Dividing Range (Map 1.4). The gold discoveries of the 1850s pushed Melbourne past Sydney to become Australia’s largest city and its financial capital. Sydney overtook Melbourne’s population around the turn of the twentieth century, but had to wait another seven decades to become the nation’s dominant financial centre.

Map 1.4. Melbourne.

The town began in 1835 as a settlement for squatters from Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), who acted independently without government authority in acquiring land illegally from the Wurundjeri population. The site chosen was on elevated ground on the north bank of the Yarra River, where a natural rock ledge separated salt water from fresh, around 16 km from the river outlet at Hobson’s Bay. Melburnians initially drew drinking water from the Yarra, but the river and its tributaries also served as sewers. The lack of strong tidal action in waterways and the Bay created difficulties in disposing of sewage. Along the 233 km course of the Yarra, floodplains and billabongs (oxbow lakes) hold water after rain and snow-melt; closer to Melbourne, the river snakes around natural obstacles before reaching an area of naturally swampy ground at the delta of the Yarra and Saltwater (Maribyrnong) rivers. Riverbanks were occupied by noxious trades that used waterways for waste disposal; poorly drained and flood-prone land nearby was occupied by manufacturing firms and worker housing. Further south, wetlands and lagoons were drained to form lakes, parkland, and building land.

Melbourne’s sprawling, low-density built environment is a product of a preference for English-style suburban living, high average incomes, and government underwriting of suburban development through the provision of public transport. The separation of port towns (Port Melbourne and Williamstown) from the city centre made early railway connections a necessity; the city grid offered space for convenient rail termini, and wide, regular streets were conducive to the operation of trams. Middle-class suburbs extended south along the Bay, and to the east and south-east through pleasant hilly country and creek valleys extending to the Dandenong Ranges. To the north and west, the land was flatter and less inviting for suburban development but offered sites for industry and worker housing. South of the Dandenong Ranges, another large, flat area known as the Carrum Swamp fed creeks leading to the Bay. When drained, the Swamp would be turned into building land for industry and suburban housing.

When Adelaide was established in 1836 by the South Australian Company, the main settlement was centred on a string of waterholes known as Karrawirra Parri by the local Kaurna people and renamed the Torrens River. Colonel William Light’s plan divided the town in two parts on either side of the river, each ringed by parklands. South Adelaide would become the business and administrative centre, while over the next century outlying villages were gradually subsumed to become the greater metropolitan area. A separate port town, Port Adelaide, was laid out.

To Adelaide’s east, the relatively low but grandly named Mt Lofty Ranges receive slightly higher annual falls (Map 1.5). Although as many as five streams now run from the ranges across the coastal plain, before white settlement they did not reach the sea, either running out of water or ending in swampy marsh areas. There are few perennial streams.

Map 1.5. Adelaide.

It took almost twenty-five years for the first reservoir to be completed, about 15 km along the Torrens, upstream from the city, while a basic sewerage system was in place by 1885. Apart from a boom in the late 1870s, the city population grew relatively slowly. However, water shortages were a regular occurrence. Despite seven major dams being constructed in the nearby hills between 1896 and 1977, before 1938 none had a capacity of 20,000 cubic metres. Only two, Mt Bold (1938) and South Para (1958), have a storage capacity over 30,000 cubic metres. To enhance water security, a pipeline to the Murray River, constructed in the late 1950s, now supplies 42 per cent Adelaide’s water, although this can be as high as 90 per cent in a drought. As further security, a desalination plant, completed in 2013, was designed to supply up to 50 per cent of Adelaide’s needs, although to date it supplies less than 2 per cent of annual consumption.

By 2021, approximately 1.3 million people lived in the greater metropolitan area of Adelaide – an urban landscape 20 km wide from east to west, and 100 km from north to south. Three major sewage plants discharge treated waste into Gulf St Vincent. The highly dispersed housing of Adelaide and suburbs has proven a challenge for infrastructure provision, although there is now a trend towards higher density living close by the city centre. Capturing and recycling storm water for drinking and reusing wastewater for gardens – both sources predicted to be essential for long-term sustainability – still only meet around 20 per cent of the city’s needs. Most stormwater is discharged to the sea, although efforts to capture and reuse this are developing apace.Footnote 22

In each of these cities, high average incomes, political stability, productive re-investment of the proceeds of resource extraction, and a preference for living in a suburban setting drove intervention in water supply infrastructure. In the twentieth century, heroic engineering solutions to water delivery and waste disposal were made possible by new construction methods and materials and government authorities with sufficient resources to pay for crucial capital works. State government bodies created the infrastructure, with high levels of private investment directed to detached dwellings in ever-growing suburbs. Housing standards for workers were comparable to those of most North American cities, but Australian workers could usually afford to rent or buy an entire house rather than share with other families. After 1890, when houses were more likely to have designated bathrooms, it became harder for public authorities to keep up with residential demand for water.

Aspirations for suburban living ‘locked-in’ a system of water movement over large distances, based on water availability, people, institutions, and legal instruments. Gravity and electric power kept dams, reservoirs, pipelines, sewerage mains, and wastewater treatment plants operating. Waterways were converted to impervious sewers, with natural creek lines drained and built over, limiting future options for storm water capture and storage. This contrasts with traditional Indigenous approaches to the availability of water sources, where in coastal areas with wetlands, rivers, and creeks small populations often relocated from one water source to another in alignment with patterns of seasonal change and abundance. These waterscapes were also valued for ceremony and sustenance, with Indigenous peoples intervening in water courses to channel eels and fish into traps and to water edible plants, as evidenced by the Gunditjmara system of kooyang (short-finned eel) aquaculture, established at least 6600 years ago in south-eastern Victoria and inscribed in 2019 on the UNESCO World Heritage List.Footnote 23

At a global scale, the modernisation of urban infrastructure that provided greater control over water in the past two centuries is a component of what Deirdre McCloskey calls the ‘Great Enrichment’, an expansion in the range of goods and services to an average standard that was denied to the average person prior to 1800. In recent years, access to clean water (and electric washing machines) has reduced the burden of carrying water and handwashing clothes on poor women. The UN Millennium Development Goals (2000), which aimed to ‘halve, by 2015, the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking-water and basic sanitation’, were achieved five years early.Footnote 24 In economist Robert Gordon’s study of living standards in the United States after the Civil War, extension and expansion of infrastructure networks is central to improvements in individual well-being, through outcomes such as lower mortality rates, improved food quality and general health, improved housing standards, and increased investment in human capital. ‘Networking inherently implies equality’, Gordon concludes, as rich and poor eventually receive access to the same water, sewers, and drains, albeit after wealthy neighbourhoods enjoy an initial advantage.Footnote 25

Detailed empirical studies of North American settler cities trace the development of what urban historian Martin V. Melosi calls the ‘sanitary city’ through the interaction of water supply and wastewater technology and the increasing sophistication of ongoing water management.Footnote 26 For cultural historical geographers Maria Kaika and Erik Swyngedouw, connecting people to network technology was a process ‘infused by relations of power’.Footnote 27 In Western European, North American, and Australasian cities, nineteenth-century urban infrastructure such as water towers, reservoirs, and pumping stations were iconic local landmarks that ‘provided the confirmation and lived experience that the road to a better society was under construction and paved with networks’, but access to these benefits was distributed unequally, and the process was marked by exclusion and segregation.Footnote 28 In Australian cities, the wealthy generally gained access earlier than the poor. As the twentieth century progressed, government subsidisation of low-income and war service loans improved access to housing, and an internal bathroom became standard in most detached suburban houses built in the interwar years. But with the exception of the wealthy, lavatories located outside (colloquially known in Australia as ‘dunnies’) or tacked on to the rear of the house prevailed, particularly in older houses.

Australia’s colonial and state governments provided the resources to meet the water needs of rapidly growing cities, yet in certain places and times infrastructure lagged or was provided in ways that imposed disproportionate costs on particular locations and their inhabitants. As Sydney drained untreated sewage into its harbour (with submarine outfalls later extended into the Pacific Ocean), low-lying areas of the city near the outlets were subject to pollution. In Melbourne and Adelaide, citizens were willing to accept sewerage as a solution to public health crises, even though this entailed higher private costs than the continued use of cesspits, pan toilets, and open drains. Australia serves as an example of the importance of political institutions, governance, and social and cultural determinants of water systems. Sustainable cities in the future are more likely to acknowledge the importance of social elements rather than disguising them within ‘technological’ responses.

In addressing urban water-related issues and crises, Australian cities responded in ways that were shaped by the current state of knowledge and perception of the nature of the problem. As cities grew, water supply and sanitation methods that were adequate in small settlements created environmental problems. In responding, colonial and local governments, private companies, and individual households pursued the easiest, lowest cost form of fresh water supply and wastewater disposal first, but the opportunity costs of such choices (the value of the next-best alternative use of resources) would rise over time. Like most aspects of the city-building process, the exploitation of water resources is a path-dependent process, highly sensitive to initial conditions that exert a lasting impact and shape and constrain subsequent land use.Footnote 29 Often the costs of decisions did not emerge for some decades. Differences in population and spatial size and structure meant that some cities could develop locally based solutions to crises, but by the twentieth century all five cities required solutions on a metropolitan scale. The Australian experience demonstrates that people were capable of changing how resources are used – at times rapidly. While change was not without cost and not without winners and losers, it was possible for large cities to be transformed into sites where human acquisition and transformation of water was reliable and abundant and met the expectations of residents and industries.

As these water systems developed, each city moved from simply tapping freshwater sources in largely ad hoc fashion to the systematic domesticating of water – shaping, regulating, and integrating water into networks of storages, pipes, and waste disposal facilities. Local government authorities proliferated in the latter half of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth century. The larger cities followed British precedent and created statutory authorities charged with responsibility for water supply, usually run by engineers, who were well informed about engineering advances in other parts of the world. These statutory authorities, or in the case of Brisbane its metropolitan-wide council formed in 1925, took over private and municipal water installations, including water towers and reservoirs. As they were able to levy water rates, these statutory authorities not only had their own relatively reliable income, they could also borrow money to build larger reservoirs and dams.

By 1901, Sydney and Melbourne were already so large that they could not continue to prosper unless their capacity to capture and store water was augmented. In all five cities, a strategy of establishing centralised management structures to build dams was pursued, despite variations in climate and local needs and despite water resources crossing State borders. This locked cities into a reliance on large, weather-dependent water storages that would inhibit change. Engineering solutions were responses to population growth that addressed supply-side issues rather than the demand for water, which was a product of cultural factors and habitually determined.Footnote 30 The adoption of Chadwickian water-flushed networks of sewage disposal created new demand for water, which led in turn to changes in the design of houses.

As the suburban frontier extended, water consumption, rather than conservation, became embedded in Australian culture, a process that interdisciplinary cultural researcher Zoë Sofoulis attributes to the rise of ‘Big Water’ – large-scaled centralised systems of single-use potable water provision.Footnote 31 Sofoulis coined the term during the Millennium Drought, as she critiqued the cultural and technical systems of Australian urban water management. Historically, settler water infrastructure for Australian cities has involved centralisation of water management, allowing for the concentration of political power and technocratic influence over environments, resources, expertise, and citizens that has persisted even with the corporatisation of the nation’s water utilities since the 1980s. Such concentration of power can have undemocratic consequences and raises questions of transparency and accountability. When Sofoulis was writing, the cultural and technical systems of Big Water were also under challenge, albeit modest, as suburban households turned to (or revived) more independent, small-scale approaches to water supply and disposal, which indicated the potential for more decentralised and flexible forms of urban water management.

From the turn of the twentieth century, city dwellers came to expect a reliable water supply, but in times of drought only severe water restrictions could ensure that the cities would not run completely dry. These interruptions pierced the complacency afforded by largely invisible networks of water provision and disposal on which urban residents relied to develop and maintain their cultures of cleanliness, convenience, and civility both inside and outside their homes.Footnote 32 Australians who moved from the country to the city – as hundreds of thousands did in both the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries – often came from locations where tank water was the only form of supply, to cities where water was supplied, either into or to the rear of homes, at the turn of a tap.

City dwellers usually paid for their water either by a fixed charge per property or, in the latter decades of the twentieth century, based on the amount they used. In a supply-focused delivery system, water meters measured use in households, industries, and businesses. But water leaving the premises – for garden use, draining from kitchen, bathroom, laundry, and toilet – has never been consistently measured. Today most households receive a quarterly water and sewerage bill, based on the assumption that the water they buy to bring into the home is the same amount that goes back into the system as sewerage.

As curator and historian Jay Arthur observes, ‘The colonist created [their] new country haunted by the image of the Default country, which was narrow, green, hilly and wet – which meant that Australia was understood as vast, brown, flat and dry’.Footnote 33 Settler Australia adopted a British framework for water management based on supply-side engineering solutions to moving water; by the late twentieth century, this approach was being challenged in response to drought, with an emphasis on ‘demand management’ solutions as well as localised rainwater capture, desalination, and the prospect of recycled water. Future climate pressures are likely to be much more demanding, and the legacy costs of past sprawl and current social and political settings (such as using markets to regulate demand and public uncertainty about scientific assurances that recycled water is safe) may make it more difficult for Australian cities to adopt more sustainable water systems at the required pace.

While Aboriginal people have not always enjoyed equal access to water in cities, Indigenous interests and rights in water were belatedly recognised in Australian national water policy in 2004; as cultural geographer Sue Jackson and Kamilaroi scientist Bradley Moggridge observe, this recognition ‘provided an impetus for change in how we manage water, and the ways in which we seek knowledge of water, as well as appreciate its critical importance to all groups in Australian society’.Footnote 34 Although Indigenous efforts to secure the protection of urban wetland sites have sometimes been controversial, urban water utilities are increasingly seeking to acknowledge and engage with relevant Elders, and local Aboriginal water stories and cultures are becoming widely featured in public art and recognised in dual naming of rivers and other water sites. Settler Australia is belatedly realising that not only does justice demand recognition of Indigenous water rights, but also that there is much to learn from Indigenous ways of relating to water, developed over generations of living with Country.

By 2021, all of Australia’s largest cities face problems that would be familiar to the residents of a century ago, albeit on a larger scale. While expecting reliable and safe water, their prosperity is threatened by the limitations of nature and the costs of maintaining, expanding, and improving existing and new networks. While new technologies, especially around water recycling, may enable a more sustainable water supply, such a dramatic change will be costly and can only happen if major political parties and voters support it, at a time when electorates are heterogeneous and public trust in governments is waning. The uneven impact of globalisation and technological change has made voters in middle and outer suburban, regional, and rural Australia more sensitive to job insecurity and cost of living pressures than those in well-off central and inner cities. Exemplifying the workings of the so-called hydro-illogical cycle, Australians are largely complacent about their real water usage and sustainability in this dry and drying continent with rapid urban development. This book aims to unsettle this uncritical approach and challenge these cultural assumptions.