I. Introduction

The subject of this chapter is statistical discrimination by means of computational profiling. Profiling works on the basis of probability estimates about the future or past behavior of individuals who belong to a group characterized by a specific pattern of behavior. If statistically more women than men of a certain age abandon promising professional careers for family reasons, employers may expect women to resign from leadership positions early on and hesitate to offer further promotion or hire female candidates in the first place. This, however, would seem unfair to the well-qualified and ambitious young woman who never considered leaving a job to raise children or support a spouse. Be fair, she may urge a prospective employer, Don’t judge me by my group!

Statistical discrimination is not new and not confined to computational profiling. Profiling, in all its variants – intuitive stereotyping, statistical in the old fashioned manner, or computational data mining and algorithm-based prediction – is a matter of information processing and a universal feature of human cognition and practice. It works on differences that make a difference. Profiling utilizes information about tangible features of groups of people, such as gender or age, to predict intangible (expected) features of individual conduct such as professional ambition. What has changed in the wake of technological progress and with the advent of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the effectiveness and scope of profiling techniques and with it the economic and political power of those who control and employ them. Increasing numbers of corporations and state agencies in some states are using computational profiling on a large scale, be it for private profit, to gain control over people, or other purposes.

Many believe that this development is not just a matter of beneficent technological progress.Footnote 1 Not all computational profiling applications promote human well-being, many undermine social justice. Profiling has become an issue of much public and scholarly concern. One major concern is police surveillance and oppression, another is the manipulation of citizens’ political choices by means of computer programs that deliver selective and often inaccurate or incorrect information to voters and political activists. Yet another concern is the loss of personal privacy and the customization of individual life. The data mining and machine learning programs which companies such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon employ in setting up personal profiles run deep into the private lives of their users. This raises issues of data ownership and privacy protection. Profiles that directly target advertisements at receptive audiences thereby streamline and reinforce patterns of individual choice and consumption. This is not an outright evil and may not always be unwelcome. Nevertheless, it is a concern. Beliefs, attitudes, and preferences are increasingly shaped by computer programs which are operated and controlled in ways and by organizations that are largely, if not entirely, beyond our individual control.

The current agitation about ‘algorithmic injustice’ is fueled both by anxiety about, and fascination with, the remarkable development of information processing technologies that has taken place over the last decades. Against this backdrop of nervous attention is the fact that the ethical problems of computational profiling do not specifically relate to the computational or algorithmic aspect of profiling. They are problems of inappropriate discrimination based on statistical estimates in general. The main difference between discrimination based on biased computational profiling and discrimination based on false intuitive prejudice and stereotyping is scale and predictive power. The greater effectiveness and scope of computational profiling increases the impact of existing prejudices and, at many points, can be expected to deepen existing inequalities and reinforce already entrenched practices of discrimination. In a world in which playing on stereotypes and biases pays, both economically and politically, it is a formidable challenge to devise institutional procedures and policies for nondiscriminatory practices in the context of computational profiling.

This chapter is about unfair discrimination and the entrenchment of social inequality through computational profiling; it does not discuss concrete practical problems, however. Instead, it tackles a basic question of contemporary public ethics: what are the appropriate criteria of fairness and justice for assessing computational profiling appropriate for citizens who publicly recognize each other as persons with a right to equal respect and concern?Footnote 2

Section I discusses the moral and legal concept of discrimination. It contains a critical review of familiar grounds of discrimination (inter alia ethnicity, gender, religion, and nationality) which figure prominently in both received understandings of discrimination and human rights jurisprudence. These grounds, it is argued, do not explain what and when discrimination is wrong (Section II 1 and 2). Moreover, focusing on specific personal characteristics considered the grounds of discrimination prevents an appropriate moral assessment of computational profiling. Section II, therefore, presents an alternative view which conceives of discrimination as a rule-guided social practice that imposes unreasonable burdens on persons (Sections II 3 and II 4). Section III applies this view to statistical and computational discrimination. Here, it is argued that statistical profiling is a universal feature of human cognition and behavior and not in itself wrongful discriminating (Section III 1).Footnote 3 Nevertheless, statistically sound profiles may prove objectionable, if not inacceptable, for reasons of procedural fairness and substantive justice (Section III 2). It is argued, then, that the procedural fairness of profiling is a matter of degrees, and a proposal is put forth as regarding the general form of a fairness index for profiles (Section III 3).

Despite much dubious and often inacceptable profiling, the chapter concludes on a more positive note. We must not forget, for the time being, computational profiling is matter of conscious and explicit programming and, therefore, at least in principle, easier to monitor and control than human intuition and individual discretion. Due to its capacity to handle large numbers of heterogeneous variables and its ability to draw on and process huge data sets, computational profiling may prove to be a better safeguard of at least procedural fairness than noncomputational practices of disparate treatment.

II. Discrimination

1. Suspect Grounds

Discrimination is a matter of people being treated in an unacceptable manner for morally objectionable reasons. There are many ways in which this may happen. People may, for instance, receive bad treatment because others do not sympathize with them or hate them. An example is racial discrimination, a blatant injustice motivated by attitudes and preferences which are morally intolerable. Common human decency requires that all persons be treated with an equal measure of respect, which is incompatible with the derogatory views and malign attitudes that racists maintain toward those they hold in contempt. Racism is a pernicious and persistent evil, but it does not raise difficult questions in moral theory. Once it is accepted that the intrinsic worth of persons rests on human features and capacities that are not impaired by skin color or ethnic origin, not much reflection is needed to see that racist attitudes are immoral. Arguments to the contrary are based on avoidably false belief and unjustifiable conclusions.

However, some persons may still be treated worse than others in the absence of inimical or malign dispositions. Fathers, brothers, and husbands may be respectful of women and still deny them due equality in the contexts of household chores, education, employment, and politics. Discrimination caused by malign attitudes is a dismaying common phenomenon and difficult to eradicate. It is not the type of discrimination, however, that helps us to better understand the specific wrong involved in discrimination. Indeed, the very concept of statistical discrimination was introduced to account for discriminating patterns of social action that do not necessarily involve denigrating attitudes.Footnote 4

Discrimination is a case of acting on personal differences that should not make a difference. It is a denial of equal treatment when, in the absence of countervailing reasons, equal treatment is required. The received understanding of discrimination is based on broadly shared egalitarian ethics. It can be summarized as follows: discrimination is adverse treatment that is degrading and violates a person’s right to be treated with equal respect and concern. It is morally wrong because it imposes disparate burdens and disadvantages on persons who share characteristics like race, color, or sex, which on a basis of equal respect do not justify adverse treatment.

Discrimination is not unequal treatment of persons with these characteristics, it is unequal treatment because of them. The focus of the received understanding is on a rather limited number of personal attributes, for example, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation, religious affiliation, nationality, disability, or age, which are considered to be the ‘grounds of discrimination’. Hence, the question arises of which differences between people qualify as respectable reasons for unequal treatment, or rather, because there are so many valid reasons to make differences, which differences do not count as respectable reasons.

In a recruitment process, professional qualification is a respectable reason for unequal treatment, but gender, ethnicity, or national origin is not. In the context of policing people based on security concerns, the relevant difference must be criminal activity and not the ethnic or national origin of an alleged suspect. Admission to institutions of higher learning should be guided by scholarly aptitude and, again, not by ethnic or national origin, or any other of the suspect grounds of discrimination. The criteria which define widely accepted reasons for differential treatment (professional qualification, criminal activity, and scholarly ability) would seem to be contextual and depend on the specific purposes and settings. In contrast, the differences that should not make a difference like ethnicity or gender appear to be the same across a broad range of social situations.

In some settings and for some purposes, however, gender and ethnic or national origin could be respectable reasons for differential treatment, such as when choosing social workers or police officers for neighborhoods with a dominant ethnic group or immigrant population. Further, in the field of higher education, ethnicity and gender may be considered nondiscriminatory criteria for admission once it is taken into account that an important goal of universities and professional schools is to educate aspiring members of minority or disadvantaged groups to be future leaders and role models. Skin color may also be unsuspicious when choosing actors for screen plays, for example, casting a black actor for the role of Martin Luther King or a white actress to play Eleanor Roosevelt.Footnote 5 Nevertheless, selective choices guided by personal characteristics that are suspect grounds of discrimination appear permissible in specific contexts and in particular settings and seem impermissible everywhere else.

This is a suggestive take on wrongful discrimination which covers a broad range of widely shared intuitions about disparate treatment; however, it is misleading and inadequate as an account of discrimination. It is misleading in suggesting that the wrong of discrimination can be explained in terms of grounds of discrimination. It is inadequate in not providing operational criteria to draw a reasonably clear line between permissible and impermissible practices of adverse treatment. Not all selective actions based on personal characteristics that are considered suspect grounds of discrimination constitute wrongful conduct. It is impossible to decide whether a characteristic is a morally permissible reason for differential treatment without considering the purpose and context of selective decisions and practices. Therefore, a further criterion is needed to determine which grounds qualify as respectable reasons for differential treatment in specific settings and which do not.

2. Human Rights

Reliance on suspect grounds for unequal treatment finds institutional support in international human rights documents. Article 2 of the 1949 Universal Declaration of Human RightsFootnote 6 contains a list of discredited reasons which became the template for similar lists in the evolving body of human rights law dealing with discrimination. It states: ‘Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.’Footnote 7 Historically, the list makes sense. It reminds us of what, for a long period of time, was deemed acceptable for the denial of basic equal rights, and what must no longer be allowed to count against human equality. In terms of normative content, however, the list is remarkably redundant. If all humans are ‘equal in dignity and rights’ as the first Article of the Universal Declaration proclaims, all humans necessarily have equal moral standing and equal rights despite all the differences that exist between them, including, as a matter of course, differences of race, color, sex etc. Article 2 does not add anything to the proclamation of equal human rights in the Declaration. Further, the intended sphere of protection of the second Article does not extend beyond the sphere of the protection of the first. ‘Discrimination’ in the Declaration means denial of the equal rights promulgated by the Document.Footnote 8

However, this is not all of it. Intolerable discrimination goes beyond treating others as morally inferior beings that do not have a claim to equal rights; and justice requires more than the recognition of equal moral and legal standing and a guarantee of equal basic rights. Article 26 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) introduces a more comprehensive understanding of discrimination. The first clause of the Article, however, contains the same redundancy found in the Universal Declaration. It states: ‘All persons are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to the equal protection of the law.’ Equality before the law and the equal protection of the law are already protected by Articles 2, 16 and 17 of the ICCPR. Like all human rights, these rights are universal rights, and all individuals are entitled to them irrespective of the differences that exist between them. It goes, therefore, again without saying, that everyone is entitled to the protection of the law without discrimination.

It is the second clause of Article 26 which goes beyond what is already covered by the equal basic rights standard of the ICCPR: ‘In this respect, the law shall prohibit any discrimination and guarantee to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.’ The broadening of scope in the quoted passage hinges upon an implicit distinction between equality before the law and equality through the law. In demanding ‘effective protection against discrimination on any ground’ without restriction or further qualification, Article 26 not only reaffirms the right to equality before the law (in its first clause), but also establishes a further right to substantive equality guaranteed through the law (in the second clause).

Equality before the law is a matter of personal legal status and the procedural safeguards deriving from it. It is a demand of equal legal protection that applies (only) to the legal system of a society.Footnote 9 In contrast, equality through the law is the demand to legally ensure equality in all areas and transactions of social life and not solely in legal proceedings. Discrimination may then violate the human rights of a person in a two-fold manner. Firstly, it may be a denial of basic equal rights, including the right to equality before the law, promulgated by the Universal Declaration and the ICCPR. Alternatively, it may be a denial of due equality guaranteed by means of the law also beyond the sphere of equal basic rights and legal proceedings.Footnote 10

If equality through the law goes further than what is necessary to secure equality before the law, a new complication for a human rights account of discrimination arises, not less disturbing than the charge of redundancy. Understood as equal legal protection of the basic rights of the Universal Declaration and the Covenant, non-discrimination simply means strict equality. All persons have the same basic rights, and all must be guaranteed the same legal protection of these rights. A strict equality standard of nondiscrimination, however, cannot plausibly be extended into all fields to be subjected to public authority and apply to social transactions in general. Not all unequal treatment even on grounds such as race, color, or sex is wrongful discrimination, and equating nondiscrimination with equal treatment simpliciter would tie up the human rights law of nondiscrimination with a rather radical and indefensible type of legalistic egalitarianism.

Elucidation concerning the equal treatment requirement of nondiscrimination can be found in both the 1965 Convention against Racial Discrimination (ICERD)Footnote 11 and in the 1979 Convention against gender discrimination (CEDAW).Footnote 12 The ICERD defines discrimination as ‘any distinction, exclusion or preference’ with the purpose or effect of ‘… nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing of human rights and fundamental freedoms’ (Article 1). The CEDAW refers to ‘a basis of equality’ between men and women (Article 1) and demands legislation that ensures “… full development and advancement of women for the purpose of guaranteeing them the exercise and enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms on a basis of equality with men” (Article 3). Following these explications, differential treatment even on one of the grounds enumerated in the ICCPR would not per se constitute illicit discrimination. It would only do so if it proved incompatible with the exercise and enjoyment of basic human rights on an equal basis or equal footing.

Both ‘equal basis’ and ‘equal footing’ suggest an understanding of nondiscrimination that builds on a distinction between treating people as equals, in other words, with equal respect and concern, but still differently and treating people equally. As a matter of equal basic rights protection, nondiscrimination means strict equality, literally speaking, equal treatment. As a matter of protection against disparate treatment that does not violate people’s basic rights, nondiscrimination would still require that everyone is treated as equal but not necessarily treated equally. Given adequate legal protection against the violation of basic human rights, not all adversely unequal treatment would then constitute a violation of the injunction against discrimination of Article 26 of the ICCPR.

The distinction between equal treatment and treatment as equals provides a suitable framework of moral reasoning and public debate and perhaps also a suggestive starting point of legal argument. ‘Equal respect’ and ‘equal concern’ effectively capture a broadly shared intuitive idea of what it takes to enjoy basic rights and liberties on the ‘basis of equality’. Yet, these fundamental distinctions and ideas allow for differing specifications. On their own and without further elaboration, they do not provide a reliable basis for the consistent and predictable right to nondiscrimination. The formula of equal respect and concern is a matter of contrary interpretations in moral philosophy. Some of these interpretations are of a classical liberal type and ultimately confine the reach of antidiscrimination norms to the sphere of elementary basic rights protection. Other interpretations, say of a utilitarian or Rawlsian type, and extend the demand of protection against supposed discriminatory decisions and practices beyond elementary basic rights protection.

The problem here is not the absence of an uncontested moral theory specifying terms of equal respect and concern. While moral philosophy and public ethics have long been controversial, legal and political theory found ways to accommodate not only religious but also moral pluralism. The problem is that a viable human rights account of discrimination must draw a reasonably clear line between permissible and impermissible conduct, and this presupposes a rather specific understanding of what it means to treat people on the ‘basis of equality’ or with equal respect and concern. The need to specify the criteria of illicit discrimination with recourse to a requirement for equal treatment based on human rights thus leads right into the contested territory of moral philosophy and competing theories of justice. Without an involvement in moral theory, a human rights account would seem to yield no right to nondiscrimination which is reasonably specific and nonredundant, given reasonable disagreement in moral theory, it seems impossible to specify such a right in a way that could not be reasonably contested.

The ambiguities of a human right to nondiscrimination also becomes apparent elsewhere. While not all differential treatment on the grounds of race, color, sex etc. is wrongful discrimination, not all wrongful discrimination is discrimination on these grounds. Article 26 prohibits discrimination not only when it is based on one of the explicitly mentioned attributes but on any ground such as race, color, sex etc. or other status. Therefore, the question arises of how to identify the grounds of wrongful discrimination and of what qualifies as an ‘other status.’ The ICCPR does not answer the question and the UN Human Rights Committee seems to be at a loss when it comes to deciding about ‘other grounds’ and ‘other status’ in a principled manner.Footnote 13

Ethnicity and gender, for instance, figure prominently in inacceptable practices of disparate treatment. However, these practices are not inacceptable because they are guided by considerations of ethnicity or gender. Racial or gender discrimination are not paradigm cases of illicit discrimination because ethnicity and gender could never be respectable reasons to treat people differently or impose unequal burdens. They are paradigm cases because ethnic and gender differences, as a matter of historical fact, inform social practices that are morally inacceptable. What then makes a practice of adversely unequal treatment that is guided by ethnicity or gender or, indeed, any other personal characteristic morally inacceptable?

In their commentary about the ICCPR, Joseph and Castan are candid about the difficulty of ascribing ‘common characteristics’ for the ‘grounds’ in Article 26.Footnote 14 It is always difficult if not impossible to add tokens to a list of samples in a rule-guided way without making contestable assumptions. Still, we normally have some indication from the enumerated samples. In the case of … table, chair, cupboard …, for instance, we have a conspicuous classificatory term, ‘furniture’, as a common denominator that suggests proceeding with ‘couch’ or ‘floor lamp’ but not with ‘seagull’. What would be the common denominator of … race, color, sex … except that these personal attributes are grounds of wrongful discrimination?Footnote 15 If exemplary historical cases are meant to guide the identification of suspect grounds, however, these grounds are no longer independent criteria that explain why these cases provide paradigm examples of discrimination and we may wonder which other types of disparate social treatment may be considered wrongful discrimination as well.

Contrary to appearance, Article 26 provides no clue as regarding the criteria of wrongful discrimination. Not all adverse treatment on the grounds mentioned in the article is wrongful discrimination and not all wrongful discrimination is discrimination on these grounds. Race, color, sex, etc. have been and continue to be grounds of intolerable discrimination. Adverse treatment based on these characteristics, therefore, warrants suspicion and vigilance.Footnote 16 However, since it is a matter of purpose and context whether adverse treatment based on a personal feature is compatible with equal respect and concern, we still need an account of the conditions under which it constitutes wrongful discrimination. Moreover, an explanation why adverse treatment is wrong under these conditions is also required. Suspected grounds of discrimination and the principle of equal basic rights offer neither.Footnote 17

3. Social Identity or Social Practice

Discrimination has many faces. It may be personal – one person denying equality to another – or impersonal where it is a matter of biased institutional measures and procedures. It may also be direct or indirect, intended or unintended. But it is never a matter of isolated individual wrongdoing. Discrimination is essentially social. It occurs when members of one group, directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally, consistently treat members of another group badly, because they perceive them as deficient in some regard. Discrimination requires a suitable context and takes place against a backdrop of socially shared evaluations, attitudes, and practices. To emphasize the social nature of discrimination not only reflects linguistic usage, it also helps us to understand what is wrong with it and to shift the attention from lists of suspect grounds to the practices and burdens of discrimination.

An employer who does not hire a well-qualified applicant because she is a woman may be doing something morally objectionable for various reasons: a lack of respect, for instance, or prejudice. If he or she were the only employer in town, however, who refused to hire women, or one of only a few, their hiring decision, I suggest, though morally objectionable, would not consitute illicit discrimination. In the absence of other employers with similar attitudes and practices, their bias in favor of male workers, though objectionable and frustrating for female candidates, does not lead to the special kind of burdens and disadvantages that characterize discrimination. Indeed, a dubious gender bias of only a handful of people may not result in serious burdens for women at all. Rejected candidates would easily find other jobs and work somewhere else. It is only the cumulative social consequences of a prevailing practice of gender-biased hiring that create the specific individual burdens of discrimination. There is a big difference between being rejected for dubious reasons at some places and being rejected all over the place.

Consider, in contrast, individual acts of wrongdoing which are not essentially social because they do not depend on the existence of practices that produce cumulative outcomes which disparately affect others. We may maintain, for instance (pace Kant) that false promising is only wrong if there is a general practice of promise-keeping. However, it would seem odd to claim that an individual act of false promising is only wrong if there is a general practice of promise-breaking with inacceptable cumulative consequences for the involved people. Unlike acts of wrongful promise-breaking, acts of wrongful discrimination do not only depend upon the existence of social practices – this may be true for promise breaking as well. They crucially hinge upon the existence of practices with cumulative consequences which impose burdens on individuals that only exist because of the practice. This suggests a social practice view of discrimination.

Social practices are regular forms of interpersonal transactions based on rules which are widely recognized as standards of appropriate conduct among those who participate in the practice. They rest on publicly shared beliefs and attitudes. The rules of a practice define spheres of optional and nonoptional action and specify types of advisable as well as obligatory conduct. They also define complementary positions for individuals with different roles who participate in the practice or who are subjected to it or indirectly affected by it. Practices may or may not have a commonly shared purpose, but they always have cumulative and noncumulative consequences for the persons involved, and any plausible moral assessment must, in one way or another, take these consequences into account.

Social practices of potentially wrongful discrimination are defined by the criteria which guide the discriminating choices of the participants, in other words, the specific generic personal characteristics which (a) function as the grounds of discrimination and (b) identify the group of people who are targeted for adverse treatment. This gives generic features of persons a central place in any conception of discrimination. These characteristics are not ‘grounds of discrimination’, however, because they adequately explain the difference between differential treatment that is morally or legally unobjectionable and treatment that constitutes discrimination. We have seen that by themselves, they do not provide suitable criteria for the moral appraisal of disparate treatment. Instead, they identify the empirical object of moral scrutiny and appraisal, in other words, social practices of differential treatment that impose specific burdens and disadvantages on the group of persons with the respective characteristics.

To reiterate, the wrong of discrimination is not a wrong of isolated individual conduct. It only takes place against the backdrop of prevailing social practices and their cumulative consequences and, for this reason, it cannot be fully explained as a violation of principles of transactional or commutative justice. This leads into the field of distributive justice. Principles of transactional justice, like the moral prohibition of false promising or the legal principle pacta sunt servanda, presuppose individual agency and responsibility. They do not apply to uncoordinated social activities or cumulative consequences of individual actions that transcend the range of individual control and foresight. Clearly, social practices of discrimination only exist because there are individual agents who make morally objectionable discriminating choices. The choices they make, however, would not be objectionable if not for the cumulative consequences of the practice of which they are a part and to which they contribute. We therefore need standards for the assessment of the cumulative distributive outcomes of individual action, in other words, standards of distributive justice that do not presuppose individual wrongdoing but rather explain it. We come back to this in the next section.

There is another train of thought which also explains the essentially social character of discrimination though, not in terms of shared practices of adverse treatment but in terms of disadvantaged social groups. Most visibly discrimination is directed against minority groups and the worse-off members of society. This may well be seen to be the reason why discrimination is wrong.Footnote 18 Is it, then, a defining feature of discrimination that it targets specific types of social groups? The list of the suspect grounds of discrimination in article 26 of the ICCPR may suggest that it is because the mentioned ground appear to identify groups that fit this description.

Thomas Scanlon and Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen have followed this train of thought in slightly different ways. By Scanlon’s account, discrimination disadvantages ‘members of a group that has been subject to widespread denigration and exclusion’.Footnote 19 On Lippert-Rasmussen’s account, discrimination is denial of equal treatment for members of ‘socially salient groups’ where a group is socially salient if ‘membership of it is important to the structure of social transactions across a wide range of social contexts’.Footnote 20 Examples of salient groups are groups defined by personal characteristics like sex, race, or religion, characteristics which, unlike having green eyes, for instance, make a difference in many transactions and inform illicit practices in various settings; salient groups, for this reason, inform social identities. This accords well with common understandings of discrimination and explains the social urgency of the issue: it is not only individuals being treated unfairly for random reasons in particular circumstances, it is groups of people who are regularly treated in morally objectionable ways across a broad range of social transactions and for reasons that closely connect with their personal identity and self-perception.

Still, neither the intuitive notion of denigrated and excluded groups nor the more abstract conception of salient groups adequately explain what is wrong with discrimination. Both approaches run the risk of explaining discrimination in terms of maltreatment of discriminated groups. More importantly, both lead to a distorted picture of the social dynamics of discrimination. While the most egregious forms of disparate treatment track personal characteristics that do define excluded, disadvantaged, and ‘salient groups’, it is not a necessary feature of discrimination that it targets only persons who belong to and identify with groups of this type.

Following Scanlon and Lippert-Rasmussen, discrimination presupposes the existence of individuals who are already (unfairly, we assume) disadvantaged in a broad range of social transactions. Discrimination becomes a matter of piling up unfair disadvantages – a case of adding insult to injury one may say. This understanding, however, renders it impossible to account for discriminating practices that lead to exclusion, disadvantage, and denigration in the first place. Lippert-Rasmussen’s understanding of salient groups creates a blind spot for otherwise well-researched phenomena of context-specific and partial forms of discrimination which do not affect a broad range of a person’s social transactions and still seriously harm them in a particular area of life. Common sense suggests and social science confirms that discrimination may be contextual, piecemeal, and, in any case, presupposes neither exclusion or disadvantage nor prior denigration of groups of people.Footnote 21

It is an advantage of the practice view of discrimination that it is not predicated on the existence of disadvantaged social groups. Based on the practice view, the elementary form of discrimination is neither discrimination of specific types of social groups that are flagged in one way or another as excluded or disadvantaged, nor is it discrimination because of group membership or social identity. It is discrimination of individual persons because of certain generic characteristics – the grounds of discrimination – that are attributed to them. Individuals who are subjected to discriminating practices due to features which they share with other persons are, because of this, also members of the group of people with these features. However, group membership here means nothing more than to be an element of a semantic reference class, that is, the class of individuals who share a common characteristic. No group membership in any sociologically relevant sense or in Lippert-Rasmussen’s sense is implied; nor is there any sense of social identity or prior denigration and exclusion.Footnote 22

To appreciate the relevance of group membership and social identities in the sociological sense of these words, we need to distinguish between what constitutes the wrong of illicit discrimination in the first place and what makes social practices of discrimination more or less harmful under some conditions than under others. Feelings of belonging to a group of people with a shared sense of identity who have been subjected to unfair discrimination for a long time and who are still denied due equality intensifies the individual burdens and harmful effects of discrimination. It heightens a person’s sense of being a victim not of an individual act of wrongdoing but of a long lasting and general social practice. Becoming aware that one is subjected to adverse treatment because of a feature that one shares with others, in other words, becoming aware that one is an element of the reference class of the respective feature, also means becoming aware of a ‘shared fate’, the fate of being subjected to the same kind of disadvantages for the same kind of reasons. And this in turn will foster sympathetic identification with other group members and perhaps also feelings of belonging. Moreover, it creates a shared interest, viz. the interest not to be subjected to adversely discriminatory practices, which in turn may contribute to the emergence of new political actors and movements.

4. Disparate Burdens

It is hard to see that we should abstain from discriminatory conduct if it did not cause harm. In all social transactions, we continuously and inevitably spread uneven benefits and burdens on others by exercising preferential choices. Much of what we do to others, though, is negligible and cannot be reasonably subjected to moral appraisal or regulation; and much of what we do, though not negligible, is warranted by prior agreements or considerations of mutual benefit. Finally, much adversely selective behavior does not follow discernible rules of discrimination and may roughly be expected to affect everybody equally from time to time. Wrongful discrimination is different as it imposes in predictable ways, without prior consent or an expectation of mutual benefit, burdens and disadvantages on persons which are harmful.Footnote 23

Not all wrongful harming is discrimination. Persons discriminated against are not just treated badly, they are treated worse than others. A teacher who treats all pupils in his class with equal contempt behaves in a morally reprehensible way, but he cannot be charged on the grounds of discrimination. The harm of discrimination presupposes an interpersonal disadvantage or comparative burden, not just additional burdens or disadvantages. It is one thing to be, like all others, subjected to inconvenient security checks at airports and other places, it is another thing to be checked more frequently and in more disagreeable ways than others. To justify a complaint of wrongful treatment, the burdens of discrimination must also be comparative and interpersonal in a further way. Adverse treatment is not generally impermissible if it has a legitimate purpose. It is only wrongful discrimination if it imposes unreasonable burdens and disadvantages on persons, burdens and disadvantages that cannot be justified by benefits that otherwise derive from it.

We thus arrive at the following explanation of wrongfully discriminating practices in terms of unreasonable or disproportionate burdens and disadvantages: a social practice of adverse treatment constitutes wrongful discrimination if following the rules of the practice – acting on the ‘grounds’ of discrimination – imposes unreasonable burdens on persons who are subjected to it. Burdens and disadvantages of a discriminatory practice are unreasonable or disproportionate if they cannot be justified by benefits that otherwise accrue from the practice on a basis of equal respect and concern which gives at least equal weight to the interests of those who are made worse off because of the practice.

It is an advantage of the unreasonable burden criterion that we do not have to decide whether the wrong of discrimination derives from the harm element of adverse discrimination or from the fact that the burdens of discrimination cannot be justified in conformity with a principle of equal respect and concern. Both the differential burden and the lack of a proper justification are necessary conditions of discrimination. Hence, there is no need to decide between a harm-based and a respect-based account of discrimination. If it is agreed that moral justifications must proceed on an equal respect basis, all plausible accounts of discrimination must seem to combine both elements. There is no illicit discrimination if we either have an unjustified but not serious burden or a serious yet justified burden.

The criterion of unreasonable burdens may appear to imply a utilitarian conception of discrimination,Footnote 24 and, indeed, combined with this criterion, the practice view yields a consequentialist conception of discrimination. However, this conception can be worked out in different ways. The goal must not be to maximize aggregate utility and balancing the benefits and burdens of practices does not need to take the form of a cost-benefit-analysis along utilitarian lines. The idea of an unreasonable burden can also be spelled out – and more compellingly perhaps – along Prioritarian or Rawlsian lines, giving more weight to the interests of disadvantaged groups.Footnote 25 We do not need to take a stand on the issue, however, to explain the peculiar wrong of discrimination. On the proposed view, it consists in an inappropriate social distribution of benefits and burdens. It is a wrong of distributive justice.

One may hesitate to accept this view. It seems to omit what makes discrimination unique, and to explain why people often feel more strongly about discrimination than about other forms of distributive injustice. What is special about discrimination, however, is not an entirely new kind of wrong; instead, it is the manner in which a distributive injustice comes about, the way in which an unreasonable personal burden is inflicted on a person in the pursuit of a particular social practice. Not all distributive injustice is the result of wrongful discrimination, but only injustice that occurs as the predictable result of an on-going practice which is regulated by rules that track personal characteristics which function as grounds of discriminating choices.

Consider, by way of contrast, the gender pay gap with income inequality in general. In a modern economy, the primary distribution of market incomes is the cumulative and unintended result of innumerable economic transactions. Even if all transactions conformed to principles of commutative or transactional justice and would be unassailable in terms of individual intentions, consequences, and responsibilities, the cumulative outcomes of unregulated market transactions can be expected to be morally inacceptable. Unfettered markets tend to produce fabulous riches for some people and bring poverty and destitution to many others. Still, in a complex market economy, it will normally be impossible to explain an unjust income distribution in terms of any single pattern of transactions or rule-guided practice. To address the injustice of market incomes we, therefore, need principles of a specifically social, or distributive justice, which like the Rawlsian Difference PrincipleFootnote 26 apply to overall statistical patterns of income (or wealth) distribution and not to individual transactions.

Consider now, by way of contrast, the inequality of the average income of men and women. The pay gap is not simply the upshot of a cumulative but uncoordinated – though still unjust – market process. Our best explanation for it is gender discrimination, the existence of rule-guided social practices, which consistently in a broad range of transactions put women at an unfair disadvantage. Even though the gender pay gap, just like excessive income inequality in general, is a wrong of distributive injustice, it is different in being the result of a particular set of social practices that readily explain its existence.

This account of wrongful disparate treatment, however, does not accord well with a human rights theory of discrimination. A viable human right to nondiscrimination presupposes an agreed upon threshold notion of nonnegligible burdens and a settled understanding of how to balance the benefits and burdens of discriminatory practices in appropriate ways. If the interpersonal balancing of benefits and burden, however, is a contested issue and subject to reasonable disagreement in moral philosophy, that which is protected by a human right to nondiscrimination would also seem to be a subject of reasonable disagreement. Given the limits of judicial authority in a pluralistic democracy, and given the need of democratic legitimization for legal regulations that allow for reasonable disagreement, this suggests that antidiscrimination rights should not be seen as prelegislative human rights but more appropriately as indispensable legal elements of a just social policy the basic terms of which are settled by democratic legislation and not by the courts.

This is not to deny that there are human rights – the right to life, liberty, security of the person, equality before the law – the normative core of which can be determined in ways that are arguably beyond reasonable dissent. For these rights, but only for them, it may be claimed that their violation imposes unreasonable burdens and, hence, constitutes illicit discrimination without getting involved with controversial moral theory. For these rights, however, a special basic right of nondiscrimination is superfluous, as we have seen in Section I.2. (If all humans have the same basic rights, they have these rights irrespective of all differences between them and it goes without saying that these rights have to be equally protected [‘without any discrimination’] for all of them.) And once we move beyond the equal basic rights into the broader field of protection against unfair social discrimination in general, the determination of unreasonable burdens is no longer safe from reasonable disagreements. Institutions and officials in charge of enforcing the human right of nondiscrimination would then have a choice, which, among the reasonable theories, would be used to assess the burdens of discrimination. Clearly, they must be expected to come up with different answers. Quite independent from general concerns about the limits of judicial discretion and authority, this does not accord well with an understanding of basic rights as moral and legal standards which publicly establish a reasonably clear line between what is permissible and what is impermissible and conformity which can be consistently enforced in a reasonably uniform way over time.Footnote 27

Let us briefly summarize the results of our discussion so far: firstly, a social practice of illicit discrimination is defined by rules that trace personal characteristics, the grounds of discrimination, which function as criteria of adverse selection.

Secondly, the cumulative outcome of on-going practices of discrimination leads to unequal burdens and disadvantages which adversely affect persons who share the personal characteristics specified by the rules of the practice.

Thirdly, the nature and weight of the burdens of discrimination are largely determined by the cumulative effects which an on-going practice of discrimination produces under specific empirical circumstances.

Fourthly, discrimination is morally objectionable or impermissible, if discriminating in accordance with its defining set of criteria imposes unreasonable burdens on persons who are adversely subjected to it.

III. Profiling

1. Statistical Discrimination

Computational profiling based on data mining and machine learning is a special case of ‘statistical discrimination’. It is a matter of statistical information leading to, or being used for, adverse selective choices that raise questions of fairness and due equality. Statistics can be of relevance for questions of social justice and discrimination in various ways. A statistical distribution of annual income, for instance, may be seen as a representation of injustice when 10% of the top earners receive 50% of the national income while the bottom 50% receive only 10%. Statistics can also provide evidence of injustice, for example, when the numerical underrepresentation of women in leadership positions indicates the existence of unfair recruitment practices. And, finally, statistical patterns may (indirectly) be causes of unfair discrimination or deepen inequalities that arise from discriminatory practices. If more women on average than men drop out of professional careers at a certain age, employers may hesitate to promote women or to hire female candidates for advanced management jobs. And, if it is generally known that statistically, for this reason, few women reach the top, girls may become less motivated than boys to acquire the skills and capacities necessary for top positions and indirectly reinforce gender stereotypes and discrimination.

Much unfair discrimination is statistical in nature not only in the technical or algorithmic sense of the word. It is based on beliefs about personal dispositions and behavior that allegedly occur frequently in groups of people who share certain characteristics such as ethnicity or gender. The respective dispositional and behavioral traits are considered typical for members of these groups. Negative evaluative attitudes toward group members are deemed justified if the generic characteristics that define group membership correlate with unwanted traits even when it is admitted that, strictly speaking, not all group members share them.

Ordinary statistical discrimination often rests on avoidable false beliefs about the relative frequency of unwanted dispositional traits in various social groups that are defined by the characteristics on the familiar lists of suspected grounds ‘… race, color, sex …’ Statistical discrimination need not be based, though, on prejudice and bias or false beliefs and miscalculations. Discrimination that is statistical in nature is a basic element of all rational cognition and evaluation; statistical discrimination in the technical sense with organized data collection and algorithmic calculations is just a special case. Employers may or may not care much about ethnicity or gender, but they have a legitimate interest to know more about the future contribution of job candidates to the success of their business. To the extent that tangible characteristics provide sound statistical support for probability estimates about the intangible future economic productivity of candidates, the former may reasonably be expected to be taken into account by employers when hiring workers. The same holds true in the case of bank managers, security officers, and other agents who make selective choices that impose nonnegligible burdens or disadvantages on people who share certain tangible features irrespective of whether or not they belong to the class with suspect grounds of discrimination. They care about certain features, ethnicity and gender for example, or, for that matter, age, education, and sartorial appearance, because they care about other characteristics that can only be ascertained indirectly.

Statistical discrimination is selection by means of tangible characteristics that function as proxies for intangibles. It operates on profiles of types of persons that support expectations about their dispositions and future behavior. A profile is a set of generic characteristics which in conjunction support a prediction that a person who fits the profile also exhibits other characteristics which are not yet manifest. A statistically sound profile is a profile that supports this prediction by faultless statistical reasoning. Technically speaking, profiles are conditional probabilities. They assign a probability estimate ![]() to a person (i) who has a certain intangible behavioral trait (G) on the condition that they are a person of a certain type (F) with specific characteristics (F’, F’’, F’’’, …).

to a person (i) who has a certain intangible behavioral trait (G) on the condition that they are a person of a certain type (F) with specific characteristics (F’, F’’, F’’’, …).

The practice of profiling or making selective choices by proxy (i.e. the move from one set of personal features to another set of personal features based on a statistical correlation) is not confined to practices of illicit discrimination. It reflects a universal cognitive strategy of gaining knowledge and forming expectations not only about human beings and their behavior but about everything: observable and unobservable objects; past and future events; or theoretical entities. We move from what we believe to know about an item of consideration, or what we can easily find out about it, to what we do not yet know about it by forming expectations and making predictions. Profiling is ubiquitous also in moral reasoning and judgment. We consider somebody a fair judge if we expect fair judgments from them in the future and this expectation seems justified if they issued fair judgments in the past.

Profiling and statistical discrimination are sometimes considered dubious because they involve adverse selective choices based on personal attributes that are causally irrelevant regarding the purpose of the profiling. Ethnicity or gender, for instance, are neither causes nor effects of future economic productivity or effective leadership and, thus, may seem inappropriate criteria for hiring decisions.

Don’t judge me by my color, don’t judge me by my race! is a fair demand in all too many situations. Understood as a general injunction against profiling, however, it rests on a misunderstanding of rational expectations and the role of generic characteristics as predicators of personal dispositions and behavior. In the conceptual framework of probabilistic profiling, an effective predictor is a variable (a tangible personal characteristic such as age or gender) the value of which (old/young, in the middle; male/female/other) shows a high correlation with the value of another variable (the targeted intangible characteristic), the value of which it is meant to predict. Causes are reliable predictors. If the alleged cause of something were not highly correlated with it, we would not consider it to be its cause. However, good predictors do not need to have any discernible causal relation with what they are predictors for.Footnote 29

Critical appraisals of computational profiling involve two types of misgivings. On the one hand, there are methodological flaws such as inadequate data or fallacious reasoning, on the other hand, there are genuine moral shortcomings, for example, the lack of procedural fairness and unjust outcomes, that must be considered. Both types of misgivings are closely connected. Only sound statistical reasoning based on adequate data justifies adverse treatment which imposes nonnegligible burdens on persons, and two main causes of spurious statistics, viz. base rate fallacies and insufficiently specified reference classes, connect closely with procedural fairness.

a. Spurious Data

With regard to the informational basis of statistical discrimination, the process of specifying, collecting, and coding of relevant data may be distorted and biased in various ways. The collected samples may be too few to allow for valid generalizations or the reference classes for the data collected may be defined in inappropriate ways with too narrow a focus on a particular group of people, thereby supporting biased conjectures that misrepresent the distribution of certain personal attributes and behavioral features across different social groups. Regarding the source of the data (human behavior), problems arise because, unlike in the natural sciences, we are not dealing with irresponsive brute facts. In the natural sciences, the source of the data is unaffected by our beliefs, attitudes, and preferences. The laws of nature are independent from what we think or feel about them. In contrast, the features and regularities of human transactions and the data produced by them crucially hinge upon people’s beliefs and attitudes. We act in a specific manner partly because of our beliefs about what other people are doing or intend to do, and we comply with standards of conduct partly because we believe (expressly or tacitly) that there are others who also comply with them. This affects the data basis of computational profiling in potentially unfortunate ways: prevalent social stereotypes and false beliefs about what others do or think they should do may lead to patterns of individual and social behavior which are reflected in the collected data and which, in turn, may lead to self-perpetuating and reinforcing unwanted feedback loops as described by Noble and others.Footnote 30

b. Fallacious Reasoning

Against the backdrop of preexisting prejudice and bias, one may easily overestimate the frequency of unwanted behavior in a particular group and conclude that most occurrences of the unwanted behavior in the population at large are due to members of this group. There are two possible errors involved in this. Firstly, the wrong frequency estimate and, secondly, the inferential move from ‘Most Fs act like Gs’ to ‘Most who act like Gs are Fs’. While the wrong frequency estimate reflects an insufficient data base, the problematic move rests on a base-rate fallacy, in other words, on ignoring the relative size of the involved groups.Footnote 31

Another source of spurious statistics is insufficiently specific reference classes for individual probability estimates when relevant evidence is ignored. The degree of the correlation between two personal characteristics in a reference class may not be the same in all sub-sets of the class. Even if residence in a certain neighborhood would statistically support a bad credit rating because of frequent defaults on bank loans in the area, this may not be true for a particular subgroup, for example, self-employed women living in the neighborhood for whom the frequency of loan defaults may be much lower. To arrive at valid probability estimates, we must consider all the available statistically relevant evidence and, in our example, ascertain the frequency of loan defaults for the specific reference group of female borrowers rather than for the group of all borrowers from the neighborhood. Sound statistical reasoning requires that in making probability estimates we consider all the available information and choose the maximal specific reference group of people when making conjectures about the future conduct of individuals.Footnote 32

2. Procedural Fairness

Statistically sound profiles based on appropriate data still raise questions of fairness, because profiles are probabilistic and, hence, to some extent under- and over-inclusive. There are individuals with the intangible feature that the profile is meant to predict who remain undetected because they do not fit the criteria of the profile – the so-called false negatives. And there are others who do fit the profile, but do not possess the targeted feature – the so-called false positives. Under-inclusive profiles are inefficient if alternatives with a higher detection rate are available and more individuals with the targeted feature than necessary remain undetected. Moreover, false negatives undermine the procedural fairness of probabilistic profiling. Individuals with the crucial characteristic who have been correctly spotted may raise a complaint of arbitrariness if a profile identifies only a small fraction of the people with the respective feature. They are treated differently than other persons who have the targeted feature but remain undetected because they do not fit the profile. Those who have been spotted are, therefore, denied equal treatment with relevant equals. Even though the profile may have been applied consistently to all ex-ante equal cases – the cases that share the tangible characteristics which are the criteria of the profile – it results in differential treatment for ex-post equal cases – the cases that share the targeted characteristic. Because of this, selective choices based on necessarily under-inclusive profiles must appear morally objectionable.

In the absence of perfect knowledge, we can only act on what we know ex-ante and what we believe ex-ante to be fair and appropriate. Given the constraints of real life, it would be unreasonable to demand a perfect fit of ex-ante and ex-post equality. Nevertheless, a morally disturbing tension between the ex-ante and ex-post perspective on equal treatment continues to exist, and it is difficult to see how this tension could be resolved in a principled manner. Statistical profiling must be seen as a case of imperfect procedural justice which allows for degrees of imperfection and the expected detection rate of a profile should make a crucial difference for its moral assessment. A profile which identifies most people with the relevant characteristic would seem less objectionable than a profile which identifies only a small number. All profiles can be procedurally employed in an ex-ante fair way, but only profiles with a reasonably high detection deliver ex-post substantive fairness on a regular basis and can be considered procedurally fair.Footnote 33

Let us turn here to over-inclusiveness as a cause of moral misgivings. It may be considered unfair to impose a disadvantage on somebody for the only reason that they belong to a group of people most members of which share an unwanted feature. Over-inclusiveness means that not all members of the group share the targeted feature as there are false positives. Therefore, fairness to individuals seems to require that every individual case should be judged on its merits and every person on the basis of features that they actually have and not on merely predictable features that, on closer inspection, they do not have. Can it ever be fair, then, to make adverse selective choices based on profiles that are inevitably to some extent over-inclusive?

To be sure, Don’t judge me by my group! is a necessary reminder in all too many situations, but as a general injunction against profiling it is mistaken. It rests on a distorted classification of allegedly different types of knowledge. Contrary to common notions, there is no categorical gap between statistical knowledge about groups of persons and individual probability estimates derived from it, on the one hand, and knowledge about individuals that is neither statistical in nature nor probabilistic, on the other. What we believe to know about a person is neither grounded solely on what we know about that person as a unique individual at a particular time and place nor independent of what we know about other persons. It is always based on information that is statistical in nature about groups of others who share or do not share certain generic features with them and who regularly do or do not act in similar ways. Our knowledge about persons and, indeed, any empirical object consists in combinations of generic features that show some stability over time and across a variety of situations. Don’t judge me by my group thus, leads to Don’t judge me by my past. Though not necessarily unreasonable, both demands cannot be strictly binding principles of fairness: Do not judge me and do not develop expectations about me in the light of what I was or what I did in the past and what similar people are like in the past and present cannot be reasonable requests.

As a matter of moral reasoning, we approve of or criticize personal dispositions and actions because they are dispositions or actions of a certain type (e.g. trustworthiness or lack thereof, promise keeping or promise breaking) and not because they are dispositions and actions of a particular individual. The impersonal character of moral reasons and evaluative standards is the very trademark of morality. Moral judgments are judgments based on criteria that equally apply to all individuals and this presupposes that they are based on generic characterizations of persons and actions. If the saying individuum est ineffabile were literally true and no person could be adequately comprehended in terms of combinations of generic characterizations, the idea of fairness to individuals would become vacuous. Common standards for different persons would be impossible.

We may still wonder whether adverse treatment based on a statistically sound profile is fair if it were known or could easily be known that the profile, in the case of a particular individual, does not yield a correct prediction. Aristotle discussed the general problem involved here in book five of his Nicomachean Ethics. He conceived of justice as a disposition to act in accordance with law-like rules of conduct that in general prescribe correct conduct but nevertheless may go wrong in special cases. Aristotle introduces the virtue of equity to compensate for this shortcoming of rule-governed justice. Equity is the capacity which enables an agent to make appropriate exemptions from established rules and to act on what are the manifest merits of an individual case. The virtue of equity, Aristotle emphasized, does not renounce justice but achieves ‘a higher degree of justice’.Footnote 34 Aristotle conceives of equity as a remedial virtue that improves on the unavoidable imperfections of rule-guided decision-making. This provides a suitable starting point for a persuasive answer to the problem of manifest over-inclusiveness. In the absence of fuller information about a person, adverse treatment based on a statistically sound profile may reasonably be seen as fair treatment, but it may still prove unfair in the light of fuller information. Fairness to individuals requires that we do not act on a statistically sound profile in adversely discriminatory ways if we know (or could easily find out) that the criteria of the profile apply but do not yield the correct result for a particular individual.Footnote 35

3. Measuring Fairness

Statistical discrimination by means of computational profiling is not necessarily morally objectionable or unfair if it serves a legitimate purpose and has a sound statistical basis. The two features of probabilistic profiles that motivate misgivings, over-inclusiveness and under-inclusiveness, are unavoidable traits of human cognition and evaluation in general. They, therefore, do not justify blanket condemnation. At the same time, both give reason for moral concern.

Statisticians measure the accuracy of predictive algorithms and profiles in terms of sensitivity and specificity. The sensitivity of a profile measures how good it is in identifying true positives, individuals who fit the profile and who do have the targeted feature; specificity measures how effective it is in avoiding false positives, individuals who fit the profile but do not have the targeted feature. If the ratio of true positives to false negatives of a profile (sensitivity) is low, under-inclusiveness leads to procedural injustice. Persons who have been correctly identified by the profile may complain that they have been subjected to an arbitrarily discriminating procedure because they are not receiving the same treatment as those individuals who also have the targeted feature but who, due to the low detection rate, are not identified. This is a complaint of procedural but not of substantive individual injustice as we assume that the person has been correctly identified and, indeed, has the targeted feature. In contrast, if the ratio of false positives to the true negatives of a profile (specificity), is high, over-inclusiveness leads to procedural as well as to substantive individual injustice because a person is treated adversely for a reason that does not apply to that individual. A procedurally fair profile is, therefore, a profile that minimizes the potential unfairness which derives from its inevitable under- and over-inclusiveness.

Note the different ways in which base-rate fallacies and disregard for countervailing evidence relate to concerns of procedural fairness. Ignoring evidence leads to over-estimated frequencies of unwanted traits in a group and to unwarranted high individual probability-estimates, thereby increasing the number of false positives, in other words, members of the respective group who are wrongly expected to share it with other group members. In contrast, base-rate fallacies do not raise the number of false positives but the number of false negatives. By themselves, they do not necessarily lead to new cases of substantive individual injustice, (i.e. people being treated badly because of features which they do not have). The fallacy makes profiling procedures less efficient than they could be if base-rates were properly accounted for and, at the same time, also leads to objectionable discrimination because the false negatives are treated better than the correctly identified negatives.Footnote 36

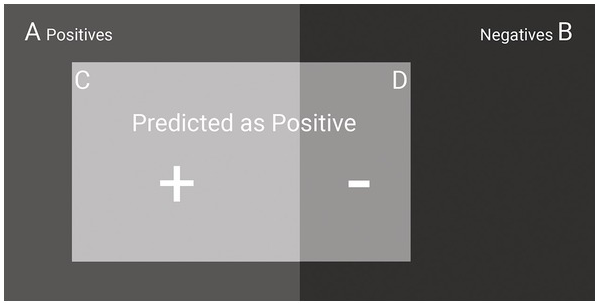

Our discussion suggests the construction of a fairness-index for statistical profiling based on measures for the under- and over-inclusiveness of profiles. For the sake of convenience, let us assume (a) a fixed set of individual cases that are subjected to the profiling procedure ![]() and (b) a fixed set of (true or false) positives (

and (b) a fixed set of (true or false) positives (![]() , see Figure 14.1). Let us further define ‘sensitivity’ as the ratio of true positives to false negatives and ‘specificity’ as the ratio of false positives to true negatives.

, see Figure 14.1). Let us further define ‘sensitivity’ as the ratio of true positives to false negatives and ‘specificity’ as the ratio of false positives to true negatives.

Figure 14.1 Fairness-index for statistical profiling based on measures for the under- and over-inclusiveness of profiles (The asymmetry of the areas C and D is meant to indicate that we reasonably expect statistical profiles to yield more true than false positives.)

The sensitivity of a profile will then equal the ratio |C| / |A| and since |C| may range from 0 to |A|, sensitivity will range between 0 and 1 with 1 as the preferred outcome. The specificity of a profile will equal the ratio |D| / |B| and since |D| may range from 0 to |B| specificity will range between 0 and 1, this time with 0 as the preferred outcome. The overall statistical accuracy of a profile or algorithm could then initially be defined as the difference between the two ratios which range between –1 and +1.

This would express, roughly, the intuitive idea that improving the statistical accuracy of a profile means maximizing the proportion of true, and minimizing the proportion of false, positives.Footnote 37

It may seem suggestive to define the procedural fairness of a profile in terms of its overall statistical accuracy because both values are positively correlated. Less overall accuracy means more false negatives or positives and, therefore, less procedural fairness and more individual injustice. To equate the fairness of profiling with the overall statistical accuracy of the profile implies that false positive and false negatives are given the same weight in the moral assessment of probabilistic profiling, and this seems difficult to maintain. If serious burdens are involved, we may think that it is more important to avoid false positives than to make sure that no positives remain undetected. It may seem more prudent to allow guilty parties to go unpunished than to punish the innocent. In other cases, with lesser burdens for the adversely affected and more serious benefits for others, we may think otherwise: better to protect some children who do not need protection from being abused, than not to protect children who urgently need protection.

Two conclusions follow from these observations about the variability of our judgments concerning the relative weight of true and false positives for the moral assessment of profiling procedures by a fairness-index. Firstly, we need a weighing factor ![]() to complement our formula for overall statistical accuracy to reflect the relative weight that sensitivity and specificity are supposed to have for adequate appraisal or the procedural fairness of a specific profile.

to complement our formula for overall statistical accuracy to reflect the relative weight that sensitivity and specificity are supposed to have for adequate appraisal or the procedural fairness of a specific profile.

Secondly, because the value of ![]() is meant to reflect the relative weight of individual benefits and burdens deriving from a profiling procedure, not all profiles can be assessed by means of the same formula because different values for

is meant to reflect the relative weight of individual benefits and burdens deriving from a profiling procedure, not all profiles can be assessed by means of the same formula because different values for ![]() will be appropriate for different procedures. The nature and significance of the respective benefits and burdens is partly determined by the purpose and operationalization of the procedure and partly a matter of contingent empirical conditions and circumstances. The value of

will be appropriate for different procedures. The nature and significance of the respective benefits and burdens is partly determined by the purpose and operationalization of the procedure and partly a matter of contingent empirical conditions and circumstances. The value of ![]() must, therefore, be determined on a case-by-case basis as a matter of securing comparative distributive justice among all persons who are subjected to the procedure in a given setting.

must, therefore, be determined on a case-by-case basis as a matter of securing comparative distributive justice among all persons who are subjected to the procedure in a given setting.

IV. Conclusion

The present discussion has shown that the moral assessment of discriminatory practices is a more complicated issue than the received understanding of discrimination allows for. Due to its almost exclusive focus on supposedly illicit grounds of unequal treatment, the received understanding fails to provide a defensible account of how to distinguish between selective choices which track generic features of persons that are morally objectionable and others that are not.

It yields verdicts of wrongful discrimination too liberally and too sparingly at the same time: too liberally, because profiling algorithms such as the Allegheny Family Screening Tool (AFST) discussed by Virginia Eubanks in her Automating Inequality that work on great numbers of generic characteristics can hardly be criticized as being unfairly discriminating for the only reason that ethnicity and income figures among the variables make a difference for the identification of children at risk. It yields verdicts too sparingly because a limited list of salient characteristics and illicit grounds of discrimination is not helpful in the identifying of discriminated groups of persons who do not fall into one of the familiar classifications or share a salient set of personal features.

For the moral assessment of computational profiling procedures such as the Allegheny Algorithm, it is only of secondary importance whether it employs variables that represent suspect characteristics of persons, such as ethnicity or income, and whether it primarily imposes burdens on people who share these characteristics. If the algorithm yields valid predictions based on appropriately collected data and sound statistical reasoning and if it has a sufficiently high degree of statistical accuracy, the crucial question is whether the burdens it imposes on some people are not unreasonable and disproportional and can be justified by the benefits that it brings either to all or at least to some people.

The discriminatory power and the validity of profiles is for the most part determined by their data basis and by the capacity of profiling agents to handle heterogeneous information about persons and generic personal characteristics to decipher stable patterns of individual conduct from the available data. The more we know about a group of people who share certain attributes, the more we can learn about the future behavior of its members. Further, the more we know about individual persons, the more we are able to know more about the groups to which they belong.Footnote 38 Profiles based on single binary classifications, for instance, male or female, native or alien, Christian or Muslim, are logically basic (and ancient) and taken individually offer poor guidance for expectations. Valid predictions involve complex permutations of binary classifications and diverse sets of personal attributes and features. Computational profiling with its capacity to handle great numbers of variables and possibly with online access to a vast reservoir of data is better suited for the prediction of individual conduct than conventional human profiling based on rather limited information and preconceived stereotypes.Footnote 39

Overall, computational profiling may prove less problematic than conventional stereotyping or old-fashioned statistical profiling. Advanced algorithmic profiling enhanced by AI is not a top-down application of a fixed set of personal attributes to a given set of data to yield predictions about individual behavior. It is a self-regulated and self-correcting process which involves an indefinite number of variables and works both from the top down and the bottom up, from data mining and pattern recognition to the (preliminary) definition of profiles and from preliminary profiles back to data mining, cross-checking expected outcomes against observed outcomes. There is no guarantee that these processes are immune to human stereotypes and void of biases, but many problems of conventional stereotyping can be avoided. Ultimately, computational profiling can process indefinitely more variables to predict individual conduct than conventional stereotyping and, at the same time, draw on much larger data sets to confirm or falsify predictions derived from preliminary profiles. AI and data mining via the Internet, thus, open the prospect of a more finely grained and reliable form of profiling, thereby overcoming the shortcomings of conventional intuitive profiling. On that note, I recall a colleague in Shanghai emphasizing that he would rather be screened by a computer program to obtain a bank loan than by a potentially ill-informed and corrupt bank manager.