Perhaps it goes without saying that a Victorian writer could not become a professional author without securing a publisher to issue her work. Today, the crucial figure in an author’s career may be her agent or editor, as the acknowledgments in many books attest; the modern publisher represents an imprint, sometimes with a distinguished history of book production, but often is just a subsidiary of a national or international conglomerate. In the Victorian period, however, publishing houses were smaller, and most publishers engaged actively in soliciting, reading, and evaluating manuscripts. Some – such as William Blackwood and Sons – were family-run businesses with several generations conducting personal and professional affairs directly with their authors; others – such as Hurst and Blackett – were businessmen who bought a failing firm (in this case Henry Colburn) and grew to become international powerhouses with offices in London, New York, and Melbourne. Whatever their origins or destinations, most Victorian publishers knew their authors personally, supported their professional careers, and helped advance their status in the literary realm. Although the relations between authors and publishers changed over the course of the century, as the last section of this chapter suggests, they remained for the most part cordial and even intimate.

Launching a career

The career of Charlotte Brontë provides a well-documented example of a publisher’s role in launching an authorial career – just as her sisters’ counter-experiences provide a negative case. All three sisters sent the manuscripts of their first novels – The Professor by Currer Bell, Wuthering Heights by Ellis Bell, and Agnes Grey by Acton Bell – to London firms known for publishing popular fiction. An unsuccessful inquiry went to Henry Colburn in July 1846; another went to Thomas Newby, who declined The Professor but accepted Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey on terms “somewhat impoverishing to the two authors.”1 In her biographical account of her sisters’ lives and works, Charlotte recalled that the three “MSS. were perseveringly obtruded upon various publishers for the space of a year and a half; usually their fate was an ignominious and abrupt dismissal.” Eventually, Charlotte found a sympathetic reader in William S. Williams of Smith, Elder, who in consultation with George Smith, the young proprietor of the firm, sent a letter declining The Professor “for business reasons” but encouraging its author to submit a three-volume work of a more striking character. Charlotte was pleased that this publisher and his literary advisor “discussed its merits and demerits so courteously, so considerately, in a spirit so rational, with a discrimination so enlightened, that this very refusal cheered the author better than a vulgarly-expressed acceptance would have done.”2 Within two months, Brontë sent the manuscript of Jane Eyre, which Smith, Elder promptly accepted and published with phenomenal success in 1847.

Although she initially received only £100 for copyright and another £400 for subsequent editions, Brontë valued her publisher for more than financial reasons. Almost immediately, she and Williams began a correspondence about contemporary novels – her own, her sisters’, Thackeray’s, as well as lesser, ephemeral works – that allowed her to analyze the achievements (and demerits) of English fiction and articulate her ars poetica. George Smith sent parcels of books his firm had published, thus giving access to recent novels and major prose such Ruskin’s Modern Painters, Hazlitt’s Essays, and Emerson’s Representative Men.3 If the correspondence with Smith remained businesslike for the first year or two, the letters to Williams soon became personal, with Charlotte offering advice about his daughters’ future careers as governesses and Williams offering medical information when Emily became seriously ill, and then solace when Emily and then Anne died. Charlotte’s publisher truly sustained her career, not only providing needed intellectual stimuli but also prodding her to write when she seemed depressed or discouraged.

Emily’s and Anne’s dealings with Thomas Newby offer a different case of author-publisher relations. Newby accepted their first novels on terms that reflected their amateur status: the sisters were required to pay £50 in advance, with the promise that the money would be refunded if their novels sold enough copies to cover expenses. Although they promptly paid the fee, Newby was dilatory in bringing out their work. As their biographer Juliet Barker notes, “While Jane Eyre was completed, typeset, bound, published, and getting its earliest reviews, [their novels] still languished at Mr Newby’s.”4 Newby’s shoddy practices resulted, moreover, in books that had not been proofread and thus were riddled with printing errors. Even after the novels met with a modest commercial success, he failed to live up to his contract. After their deaths, when pressed for a financial account by Charlotte, Newby asserted that “he realized no profit” and had “sustained actual loss,” further claiming that any profits from sales had gone toward advertisements, as the authors had wished.5 Charlotte wryly observed to George Smith that no ads had ever been seen. Only when Smith intervened and brought out a new edition of Wuthering Heights and Agnes Grey in 1850, with a biographical preface composed by Charlotte, did these novels gain a secure future. Indeed, both might have sunk into oblivion without Smith, Elder’s intervention.

Although the Brontë sisters provide the best-known cases of positive and negative relations with publishers, the contrasts recur in the biographies of other Victorian women, sometimes within the career of a single author. In her autobiographical novel A Struggle for Fame (1883), for instance, Charlotte Riddell (1832–1906) describes the mentoring she received as a young novelist from an old-fashioned publisher, Mr. Vassett, modeled on Charles Skeet of King William Street. When her heroine Glen asks for advice, Vassett claims that he cannot give her a formula for a successful novel: “If I could publish a key to the problem you want to solve[,] it would sell so well, I should never need to bring out another book. The land you want to enter has no itinerary—no finger posts—no guides” (I, 123). Despite the lack of professional tips, Riddell later praised Skeet for his early support and enduring friendship, noting in an interview for the Lady’s Pictorial that he had published her youthful fiction The Rich Husband (1858), Too Much Alone (1860), and The World and the Church (1862), and thus launched her career. She also praised George Bentley, “though he, like everyone else, refused my work; still I left his office not unhappy, but thinking much more about how courteous and nice he was.” Riddell even commented favorably on Thomas Newby, who accepted her first novel, Zuriel’s Child (1856): “I could always, when the day was frightfully cold … turn into Mr. Newby’s office in Welbeck Street, and have a talk with him and his ‘woman of business,’ Miss Springett.”6

In Riddell’s view, these early Victorian publishers were closer to amateurs than professional businessmen. In A Struggle for Fame, she contrasts an amateur “then” with a professional “now,” the former an era when “in the literary world females still retained some reticence, and males the traditions at least of self-respect” (I, 103), the latter a professionalized era when authors became more businesslike and market conscious, if also more “pushing” and “hopelessly impecunious” (I, 103). Like Riddell, her heroine leaves the old-fashioned, gentlemanly Vassett for the trendy firm of Felton and Laplash (based on the Tinsley Brothers). Once she moves, she achieves great popular success – as Riddell did with George Geith of Fen Court (1864). But now male authors and reviewers treat her as a professional rival, using periodical reviews to damn or downgrade her work. Even her publisher gives little support in sustaining her career and eventually throws her over when her novels fail to sell. Thus, in negotiating with commercial publishers like Tinsley Brothers, Riddell left behind the gentler, kinder world of early Victorian publishing, where relations between author and publisher were cordial, if sometimes also paternal, and entered a new publishing world of market-driven choices, industrialized production, and commercial profit over literary product. This brave new world dominated, in Riddell’s view, the late Victorian literary scene.

Developing a career

If publishers were essential to launching a woman writer’s career, they also played an important role in its development. The literary successes of Margaret Oliphant (1828–97), novelist, biographer, and reviewer; of Christina Rossetti (1830–94), poet and devotional writer; and of Alice Meynell (1847–1922), poet and essayist, show this role in different ways.

Oliphant launched her career more or less on her own, using her brother Willie to negotiate with London publishers and place her work with firms known for popular fiction, Henry Colburn and Hurst & Blackett. When she wrote Katie Stewart (1852), a Scottish historical novel based on family tales, she turned to the Edinburgh publisher William Blackwood and Sons. With Blackwood, she found a publisher who would support her during hard times, assign book reviews and columns to supplement income, and eventually make her “general utility woman” to the house organ, Blackwood’s Magazine. After the success of Katie Stewart, Oliphant serialized other novels in Blackwood’s Magazine and added columns about past and recent fiction to her dossier; throughout the 1850s, she anonymously reviewed Thackeray, Dickens, Bulwer, and other modern novelists in “Maga,” as William Blackwood called it. In 1859, when her husband became ill with tuberculosis, the family traveled to Italy for the warmer climate, with Blackwood accepting travel pieces, offering translation work, and sending financial advances to aid the family. As Oliphant’s biographer Elisabeth Jay notes, “John Blackwood undoubtedly became her banker, reviewer, literary adviser, and friend.”7

When her husband died and left her a widow with three young children, Oliphant hit a low point, unable to write articles or stories that the Blackwoods would accept. In her Autobiography (1899), she tells of summoning up the courage to visit the firm’s Edinburgh office and offer a novel face-to-face to John Blackwood and “Major” Blackwood, “both very kind and truly sorry for me,” but shaking their heads and saying “it would not be possible to take such a story.”8 In fact, this encounter marked the turning point in her career and her relations with the firm. Oliphant returned home that night to compose “The Executor” (1861), the first story of her Carlingford series, “which made a considerable stir at the time, and almost made me one of the popularities of literature” (70). Thereafter, she published more than twenty volumes of fiction, biography, and history with Blackwoods and typically placed half a dozen articles in “Maga” each year, including regular columns, “The Old Saloon” and “The Looker-on,” during the last decade of her life. Yet, as Jay notes, this close relationship “remained essentially one of patronage” and perhaps hindered Oliphant’s career,9 if only because she never felt she could negotiate prices with a publisher to whom she was in debt. Nonetheless, during this period, 1860–95, she also sustained cordial friendships and publishing relations with George Craik of Macmillans and Henry Blackett of Hurst & Blackett, with whom she published roughly thirty books each. Oliphant’s friendships with these men and their families, especially with Isabella Blackwood and Ellen Blackett, became the core of her social life, giving her much pleasure and stability – not just commercial outlets for her work.

Christina Rossetti never developed this sort of intimate relationship with her publisher, Alexander Macmillan, but when his editor David Masson accepted several lyrics for Macmillan’s Magazine, Macmillan himself wrote to encourage a collection that became Goblin Market and Other Poems (1862) – and thus helped launch her adult career. As an adolescent, Rossetti had published verse under the pseudonym “Ellen Allyne” in The Germ, the periodical of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood edited by her brother William Michael Rossetti. When the short-lived Germ folded after three issues, Christina lost an outlet for her poetry. She reverted to contributing to a ladies’ magazine, The Bouquet from Marlybone Gardens, funded by subscription, and to placing occasional poems in minor literary annuals. The appearance of “Uphill” and “A Birthday” in Macmillan’s Magazine in 1861 changed all this – including Rossetti’s psychological state. Initially deferential, she soon was writing enthusiastically to Macmillan about the projected collection, happily acknowledging her desire “to attain fame(!) and guineas by means of the Magazine.”10 Macmillan, in turn, worked to promote a poet whose excellence he recognized. He asked for a photograph to include in his magazine, urged a second volume after the success of Goblin Market, and served as primary publisher of her poetry, issuing The Prince’s Progress and Other Poems (1866), New Poems (1896), and the posthumous Poetical Works of Christina Georgina Rossetti (1904), edited by William Michael. This relationship with a distinguished publisher allowed Rossetti to develop her skills and status as a leading Victorian poet.

Alice Meynell (née Thompson), a poet of the late nineteenth century who admired Rossetti’s work and composed love lyrics in her strain, started her own literary career with Preludes (1875), a collection published by Henry S. King. Although Meynell’s father most likely financed the volume, it was a coup in that Meynell placed her work with a firm known for literary excellence, especially in poetry. With Preludes, Meynell garnered private praise from Alfred Tennyson, Coventry Patmore, Aubrey de Vere, and John Ruskin, as well as positive reviews in such periodicals as the Pall Mall Gazette. Unfortunately, as Meynell recounts the story, the poems disappeared from public view when King’s warehouse burned to the ground and the volumes were lost. Fortunately, Meynell’s poetry was rediscovered fifteen years later when an editor and a publisher – William Henley of the Scots Observer and John Lane of the Bodley Head Press – recognized the high quality of Meynell’s work.

By then, the early 1890s, Meynell had established a professional reputation as an art critic and essayist; she wrote regular reviews for the Magazine of Art and Art Journal, occasional pieces for the Spectator, Saturday Review, Illustrated London News, and others, and she edited Merry England and the Weekly Register with her husband Wilfrid.11 Yet it was the appearance of her brief essays in the Observer – all stylishly polished, despite their spontaneous, almost breathless effect – that brought her to the attention of John Lane and secured her fame. Via Henley, Lane asked if he might publish a volume of essays drawn from Meynell’s Observer columns. The result was The Rhythm of Life and Other Essays (1893), with its title taken from one of her most famous pieces, and Poems (1893), a reissue of verses from Preludes with the addition of some new lyrics. Although Meynell’s relationship with Lane was always polite and professional, never deeply personal or intimate, it was crucial to her career. Lane’s role as the leading publisher of aesthetic and decadent writers enabled her to make a transition from professional journalist to prominent woman of letters in fin-de-siècle literary culture. His continuing support – from 1892 with Poems and The Rhythm of Life to 1901 with Later Poems – stamped Meynell’s work as top flight. Lane’s shrewd eye for advertising, moreover, kept her poetry in the public view – as in his 1895 interview for The Sketch, in which he presents Meynell as a modern Sappho and lists her first among the “five great women poets of the day.”12 As we shall see in the next section, maintaining an ongoing relationship with a publisher was crucial to sustaining literary status and a professional career.

Consolidating a career

Novelists like Oliphant and poets like Rossetti and Meynell could count on their publishers to regularly accept and issue their submissions. This assurance enabled them to place work in their signature genres, develop skills in others, and consolidate their literary reputations. In no cases was the publisher more crucial (positively) than in the career of George Eliot (1819–80) and (negatively) in the experience of her admirer, the novelist Mary Cholmondeley (1859–1925).

Marian Evans, who adopted the nom-de-plume George Eliot, was a notoriously sensitive author. She entered the London literary world as assistant editor to John Chapman on the Westminster Review, eventually fulfilling most of the editorial duties and contributing original, but anonymous articles to the periodical. Although her contributions were known to insiders, the policy of anonymity shielded her from public scrutiny and assessment. After eloping with fellow writer George Henry Lewes, Eliot continued this periodical work but, at Lewes’s suggestion, in 1856 she turned her hand to writing fictional sketches, “Scenes of Clerical Life.” Lewes sent the first “Scene” to John Blackwood as the manuscript of “a friend who desires my good offices with you”; Lewes added, “I confess that before reading the m.s. I had considerable doubts of my friend’s power as a writer of fiction; but after reading it those doubts were changed into very high admiration.”13 Blackwood concurred with this judgment, writing that “this specimen of Amos Barton is unquestionably very pleasant reading” and asking to see more stories for publication in Blackwood’s Magazine.

Typically but unwisely in this instance, Blackwood continued his letter of acceptance with an evaluation of Eliot’s submission, “The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton.” He praised the death of Milly as “powerfully done” but called the “windup” the “lamest part of the story”; he admired the descriptions as “very humourous and good” but criticized “the error of trying too much to explain the characters.”14 In making these comments, Blackwood was following his usual practice with submissions: offering a balanced account from a typical, but shrewd reader. Eliot did not see the balance, however, only the critique. After receiving Blackwood’s letter, Lewes wrote that his “clerical friend” was “somewhat discouraged by it,” adding that he rated “the story much higher than you appear to do from certain expressions in your note.”15 When Blackwood continued sending his evaluations of strengths and weaknesses, Lewes had to explain that his friend was “unusually sensitive” and “afraid of failure though not afraid of obscurity”; at one point, after witnessing the depressing effect of a letter on Eliot, he advised outright: “Entre nous let me hint that unless you have any serious objection to make to Eliot’s stories, don’t make any.”16 Blackwood took the hint and became, as Gordon Haight notes, “next to Lewes,” the one who “did most to develop and sustain George Eliot’s genius as a novelist.”17

This sustenance included more than repeated reassurances and unstinting praise for Eliot’s fiction. After the publication of her first novel, Adam Bede (1859), Blackwood sent his cousin to search “in all the dog-fancying regions of London” for a pug – having heard that Eliot liked this breed and had recently lost an elder sister.18 The day after her sister’s funeral, Blackwood sent the manuscript of Adam Bede, “beautifully bound in red russia.”19 On a more practical level, Blackwood kept Eliot in the public eye with ample and frequent advertisements of her work. Taking the advice of his London manager, Joseph Langford – “George Eliots [sic] books sell more like Holloway Pills than like books and it pays to keep them before the public by advertising” – Blackwood agreed, writing to Langford: “By all means keep them before the public.”20

Even when she defected to another publisher who offered more money for her novel Romola (1863), Blackwood maintained cordial relations. To Langford, he privately wrote: “The going over to the enemy without giving me any warning and with a story on which from what they both said I was fully intitled [sic] to calculate upon, sticks in my throat but I shall not quarrel—quarrels especially literary ones are vulgar.”21 With Eliot, however, he adopted the principle of “not quarreling,” noting in a speech he later gave at the centenary of Scott’s birth that Sir Walter’s relations with publishers had been notably stormy but that, for him, “authors were among his dearest friends.”22 Eliot concurred. After her brief defection, she returned to Blackwoods with her next novel, Felix Holt (1866), and stayed with the firm for the rest of her career. In October 1876, when John Blackwood was seriously ill, Eliot wrote to thank him for all his encouragement throughout the years.23 On hearing of his approaching death, she commented: “He will be a heavy loss to me. He has been bound up with what I most cared for in my life for more than twenty years, and his good qualities have made many things easy to me that without him would often have been difficult.”24

Of course, John Blackwood and his nephew William, who joined the firm in 1857, had more than friendship at stake in their relationship with George Eliot. As David Finkelstein notes in The House of Blackwood, Eliot’s books represented a “tangible capital asset,” in that they became a “mainstay of the company profits between 1860 and 1900,” regularly generating more than £1000 per year.25 On the novelist’s side, the relationship was profitable too, in that Eliot moved from the relative poverty of periodical writing to the financial comfort that Blackwoods’ solid, if not extraordinary payments for fiction brought: from Adam Bede (£800 in 1858, another £800 in 1859) to Daniel Deronda (£4000 in 1873–76).

Such mutual benefit did not always pertain in author-publisher relations. Mary Cholmondeley, a writer who admired Eliot’s fiction and incorporated Eliot’s aphoristic style into her own novels, lacked the sustaining relationship with a publisher that her predecessor achieved. Cholmondeley’s career started well with George Bentley, of Richard Bentley & Son, whom she met in the mid-1880s via friend and fellow novelist Rhoda Broughton. Bentley accepted Cholmondeley’s first novel The Danvers Jewels (1887), praising “your bright and humorous story” in his acceptance letter and urging that she “continue to give me the benefit of such papers.”26 He accepted her next two novels for publication in periodical and book format, paying £50 for the copyright of Sir Charles Danvers (1889), increasing her royalties as her sales and reputation rose,27 and offering £400 for Diana Tempest (1893), then adding a £100 bonus after the novel went into a fifth edition.28 These rates fall below those paid to George Eliot by Blackwoods or by Bentley to Broughton, who often sold the copyright of her popular novels for £800, but they represent Bentley’s estimate of Cholmondeley’s solid worth.

Bentley soon became an intimate correspondent, offering medical advice and encouragement when Cholmondeley found herself seriously ill with asthma and addicted to morphine for relief. Perhaps because he too suffered from asthma, she found his letters sincere and helpful. Her biographer, Carolyn Oulton, suggests that empathy with Bentley as a fellow asthmatic and an ongoing struggle to meet his deadlines “led her to confide in him about the details of her illness in ways that are not paralleled elsewhere in her correspondence.” Oulton adds that Cholmondeley may not have continued her writing career without this personal support.29

When George Bentley died in 1895, however, and his son Richard sold the business to Macmillan, Cholmondeley lost a steady, reliable outlet for her fiction. The publisher’s archive does not make clear if Macmillan wished to drop this woman author, known for writing sensational fiction, a genre that was going out of fashion, or if he simply did not keep up with the correspondence required by the business transition. In any case, Cholmondeley felt neglected and unwanted. When Macmillan did not inquire about her new work, she took her next novel A Devotée (1897) and the plan for Red Pottage (1899), her most famous, to Edward Arnold. After Red Pottage’s phenomenal success (it went into a fifth edition within a year), Macmillan wrote to ask why she had left the firm. She responded that she supposed “you would have written to me had you wished for the new book on which Mr. Bentley knew I was engaged,” admitting that she was “disappointed that I only heard from you when several months had elapsed, and when I was in treaty with another publisher.” In a subsequent letter, written after Macmillan apologized for his lapse, Cholmondeley added:

I was a very small writer and you are a very great publisher. It never entered my head to write to you. But I will frankly own I was deeply disappointed at not hearing from you … Until I received your letter of June 24th [1900] I had remained under the impression that the firm did not value my books.30

Cholmondeley’s impression – that Macmillan had quietly dropped her and resumed correspondence only after she published a best seller – seems accurate, given the five-year hiatus in the correspondence. Whether Macmillan had initially intended to “edge out” this particular woman writer, as Gaye Tuchman and Nina Fortin suggest that the firm systematically did to other women,31 remains unknown, but it raises a larger question of how gender aided or disabled Victorian women in their relations with publishers.

Gender variants in author-publisher relations

Analyzing the Macmillan publishing archive of the mid-to-late nineteenth century, Tuchman and Fortin argue that 1840–79 saw male authors in “a period of invasion,” challenging women’s dominance in “the novel as a cultural form”; they posit that a “period of redefinition,” 1880–99, followed this invasion, “when men of letters, including critics, actively redefined the nature of a good novel” and demoted women’s fiction to the status of popular (low) culture.32 These insights into late-Victorian publishing have sometimes led scholars to assume that women authors tended always to be edged out or that publishers routinely valued their work less than that of their male counterparts. Such assumptions are troublesome because, as Tuchman and Fortin carefully note, some publishers (e.g., Tinsley) “viewed themselves as specialists in popular fare” and thus, unlike Macmillan, which began as an academic publishing house, actively sought and even preferred women’s fiction.33 Furthermore, such assumptions are troublesome because they fail to account for different genres, different publishing media, and changing literary norms across the century – factors that affected both male and female authors.

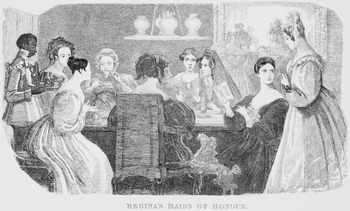

If we turn to the 1830s and consider two famous illustrations of prominent authors – “The Fraserians” and “Regina’s Maids of Honour,” published in Fraser’s Magazine in January 1835 and January 1836, respectively – we might conclude that a gender division similarly dominates the early Victorian literary field, promoting male authors and demoting women (see Figures 1 and 2). “The Fraserians” depicts twenty-six male authors and their publisher seated around a table, lifting their glasses in toast of the magazine, its editor, and their recently deceased comrade Edward Irving.34 “Regina’s Maids of Honour,” in contrast, depicts eight women – poets, novelists, and editors of literary annuals – drinking tea and engaging in conversation, “with volant tongue and chatty cheer,” as the text explains, “welcoming in, by prattle good, or witty phrase, or comment shrewd, the opening of the gay new year.”35 Notably, the illustration of male authors includes a publisher – James Fraser, who took an active interest in the magazine and its contributors – whereas the women authors appear publisher-less. Is this absence the result of women’s actual lack of close relations with publishers, or does it rather represent a careful minimizing of certain professional aspects of authorship that might harm a woman’s social status? Probably both. Some women writers depicted in “Regina’s Maids” had no well-established relationship with a publisher; others had productive, often long-standing relations with publishers and their firms, though they may not have foregrounded these relations in their public self-presentations.

Figure 1. “The Fraserians,” Fraser’s Magazine 11 (January 1835), 2–3.

Figure 2. “Regina’s Maids of Honour,” Fraser’s Magazine 13 (January 1836), 80.

For example, Mary Mitford (1787–1855), one of the women authors in “Regina’s Maids,” had a regular publisher for her drama, George Whittaker – though, unfortunately for her, she sold him the copyright of most of her plays and of Dramatic Scenes, Sketches, and Other Poems (1827) and never realized the significant profits of their commercial success.36 Later, after the enormous popularity of her prose sketches Our Village, published serially in the Lady’s Magazine between 1822 and 1824, Mitford easily placed her work with various popular publishers such as Saunders and Otley, Colburn and Bentley, and Hurst & Blackett. In contrast, the poetess Laetitia Landon (1802–38) bounced from publisher to publisher with the early volumes of her verse: J. Warren for The Fate of Adelaide in 1821; Hurst and Robinson for The Improvisatrice in 1824 and The Troubadour in 1825; Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans for The Golden Violet in 1827. Ironically, her most reliable publisher was the American firm Carey and Hart of Philadelphia, which regularly pirated her books (paying no royalties, needless to say). Harriet Martineau (1802–76), Landon’s contemporary, found a steady outlet for her early essays and reviews in the Unitarian magazine Monthly Repository, and for her juvenile tales with the religious publisher Houlston and Son. But when she attempted to place Illustrations of Political Economy (1832–34), a series of didactic prose tales, with a London publisher, she encountered repeated refusals. At a time of economic slump, with cholera in London and the first Reform Bill in Parliament, they feared readers would never pay ready money for such tales. Martineau had to settle for demeaning terms with Charles Fox, who nonetheless profited from the Illustrations’ enormous success. By 1836, when Fraser’s published “Regina’s Maids,” in which Martineau was included, she was an acknowledged successful author for whose books publishers competed.

The varying experiences of women authors in the 1820s and 1830s are not so different from those of their male counterparts in that they reflect the slump in book publishing, the downturn in markets for poetry, and a rising interest in prose. Coleridge (1772–1834), included in “The Fraserians” but dead by the time it appeared in print, used various printers to issue his poetry and prose, though by the 1820s the London firm, W. Pickering, became the regular publisher of his verse. Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881), a young author in 1835, had placed articles in London and Edinburgh periodicals but faced almost insurmountable obstacles in securing a book publisher for his satirical masterpiece Sartor Resartus and initially settled for serialization in Fraser’s Magazine. In 1835, William Thackeray (1811–63) did not even have a publisher to turn to; as Peter L. Shillingsburg quips, “During the years of struggle to establish himself as a writer, Thackeray can hardly be said to have ‘had a publisher.’”37 Once Thackeray established a relationship with Smith, Elder at mid-century, he could count on dual publication of his fiction in the Cornhill Magazine and in three-volume (triple-decker) format. The experiences of these male authors, like those of their female counterparts, confirm the volatility of the publishing world in the early Victorian period – in contrast to the relative stability that mid-Victorian authors such as Brontë, Oliphant, and Eliot enjoyed with their steady relationships with Smith, Elder and Blackwood.

Stability does not mean that author-publisher relations were gender neutral. As “The Fraserian” hints, male authors enjoyed an easy conviviality with publishers, the latter often hosting dinners on their premises for leading contributors. Moreover, as Joanne Shattock observes, male authors could join London clubs at which they might meet other authors, editors, and publishers.38 Women did not receive invitations to such publishers’ dinners, nor were they able to join London clubs for most of the century. Like male authors, women could attend literary salons, large evening parties, and small “at homes.” And some, like Oliphant, had personal relationships with publishers that extended to informal suppers, holiday visits, and even travel abroad.

Yet Oliphant, who had such friendships with the Blackwoods and the Blacketts, complained that the paternalistic relationship she fell into with the elder Blackwoods, fueled by a constant need for funds to sustain her household, meant she could never bargain for high payments. Such paternalism certainly had a gender component: “I took what was given me and was very grateful,” she comments in her Autobiography.39 Even so, in terms of successful financial negotiations with publishers, Oliphant compared herself not to male counterparts but to Dinah Mulock (later Craig). Mulock, whom Oliphant introduced to Hurst and Blackett, negotiated successfully over payments for John Halifax, a best-selling novel, and her subsequent fiction; “she made a spring thus quite over my head with the helping hand of my particular friend, leaving me a little rueful.” Mulock was a publisher’s terror, however: “it was Henry Blackett who turned pale at Miss Mulock’s sturdy business-like stand for her money”40 – a masculine trait Oliphant presumably chose not to acquire.

Thus, when we raise the question of publishers’ impact on Victorian women’s writing, we must consider various factors: the period in which women published and its economic realities, the generic preferences of the firm and its readers, the personalities of both author and publisher, and the changing literary forms that enabled (or disabled) both men and women to place their work advantageously. Women writers often faced obstacles, as both Alexis Easley (“Making a Debut,” ch. 1) and Joanne Shattock (“Becoming a Professional Writer,” ch. 2) document, but those of high achievement usually found the ways and means to establish productive author-publisher relations.