Book contents

- Shakespeare and the Admiral’s Men

- Shakespeare and the Admiral’s Men

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Dating

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 ‘How might we make a famous comedie’

- Chapter 2 ‘Hobgoblins abroad’

- Chapter 3 ‘I speak of Africa and golden joys’

- Chapter 4 ‘Sundrie variable and pleasing humors’

- Chapter 5 ‘Nor pure religion by their lips profaned’

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

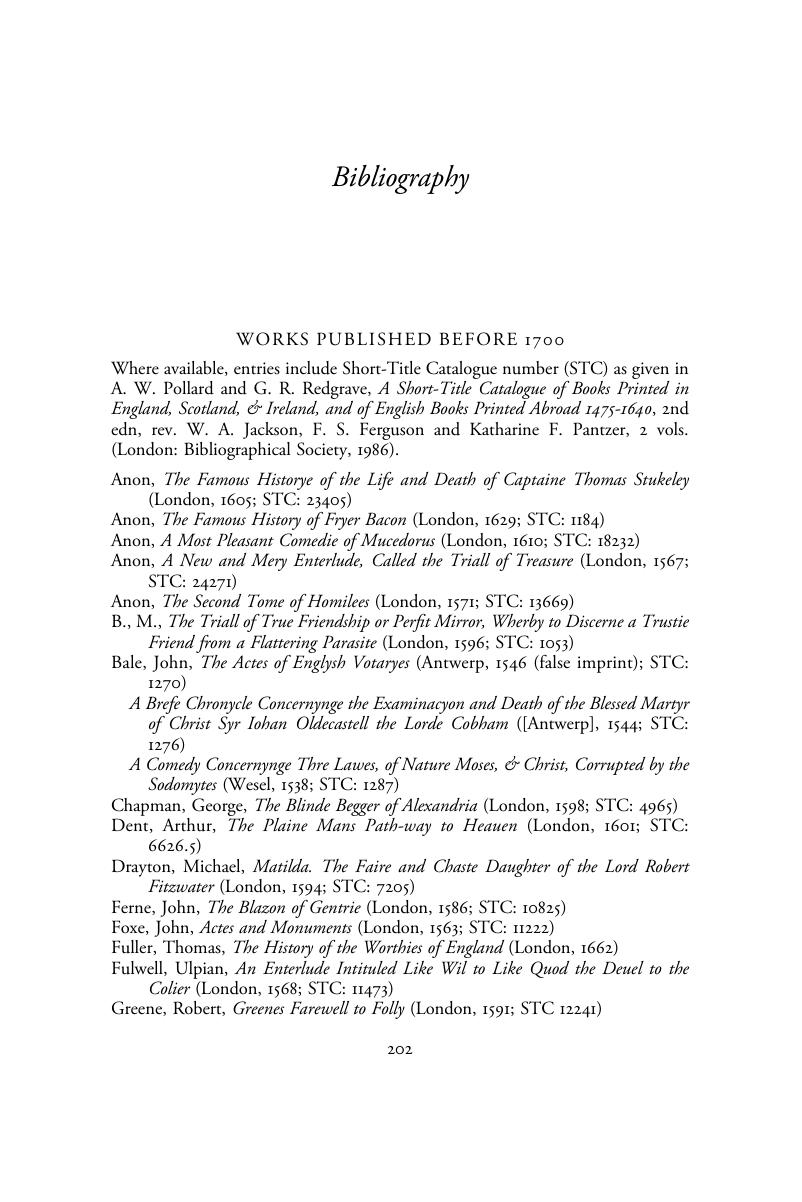

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 March 2017

- Shakespeare and the Admiral’s Men

- Shakespeare and the Admiral’s Men

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Dating

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 ‘How might we make a famous comedie’

- Chapter 2 ‘Hobgoblins abroad’

- Chapter 3 ‘I speak of Africa and golden joys’

- Chapter 4 ‘Sundrie variable and pleasing humors’

- Chapter 5 ‘Nor pure religion by their lips profaned’

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Shakespeare and the Admiral's MenReading across Repertories on the London Stage, 1594–1600, pp. 202 - 220Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017