Book contents

- Navigating Nationalism in Global Enterprise

- Cambridge Studies in the Emergence of Global Enterprise

- Navigating Nationalism in Global Enterprise

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Nationalism and Competitive Dynamics

- Part II Emergent Strategy in a World of Nations

- Conclusion: Rehistoricizing Nations

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

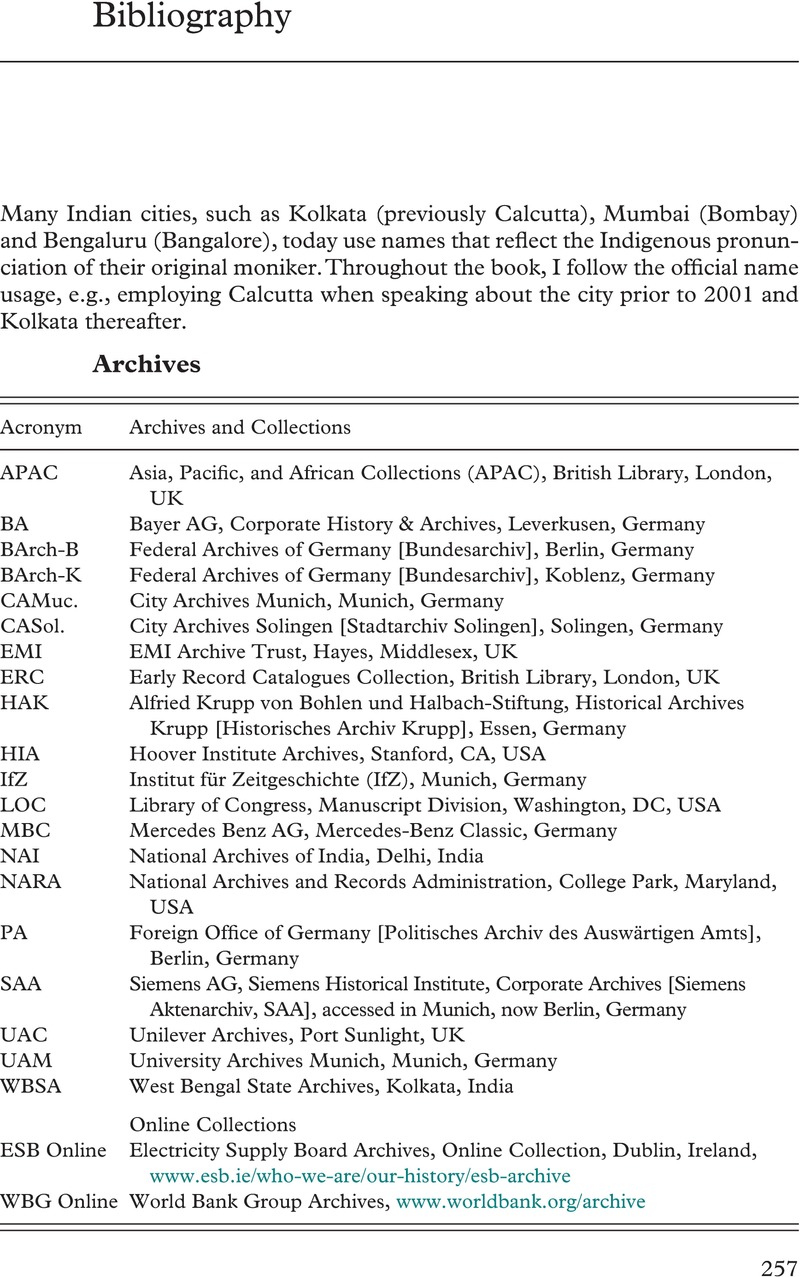

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2022

- Navigating Nationalism in Global Enterprise

- Cambridge Studies in the Emergence of Global Enterprise

- Navigating Nationalism in Global Enterprise

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Nationalism and Competitive Dynamics

- Part II Emergent Strategy in a World of Nations

- Conclusion: Rehistoricizing Nations

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Navigating Nationalism in Global EnterpriseA Century of Indo-German Business Relations, pp. 257 - 283Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022