I - Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 30 August 2017

Summary

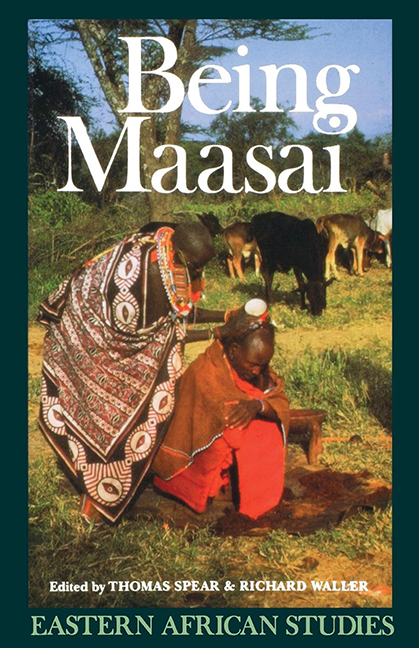

Everyone ‘knows’ the Maasai. Men wearing red capes while balancing on one leg and a long spear, gazing out over the semi-arid plains stretching endlessly to the horizon, or women heavily bedecked in beads, stare out at us from countless coffee-table books and tourists’ snapshots. Uncowed by their neighbours, colonial conquest, or modernization, they stand in proud mute testimony to a vanishing African world.

Or so we think. Reality is, of course, different. Long considered archetypical pastoralists, Maasai are in fact among the most recent arrivals on the East African scene; their adoption of a purely pastoral way of life is an even more recent innovation; and many people who speak Maa, the Maasai language, and call themselves Maasai are not pastoralists at all. We must re-examine carefully the myths surrounding Maasai identity and, in so doing, question our thinking regarding ethnicity generally.

The ancestors of modern Maa-speakers came from the southern Sudan sometime during the first millennium AD. Slowly moving down the Rift Valley that cuts through central Kenya and Tanzania, they eventually supplanted or absorbed most previous inhabitants of this semi-arid savannah bisecting the fertile highlands on either side. Originally agropastoralists, raising sorghum and millet along with their cattle and small stock, they came to specialize more and more in a pastoral way of life appropriate for the plains, leaving grain production to communities of farmers inhabiting the fertile highlands either side of the valley and hunting and gathering to specialized groups who lived in the forests bordering the highlands and plains. Over time, pastoral Maasai and others increasingly came to see this division of labour in exclusive ethnic terms as the Rift world became cognitively divided among Maa-speaking pastoralists, Bantu farmers, and Okiek hunter-gatherers.

Such a neat, tripartite division never really matched the complex realities of life in the Rift, however, where periodic droughts, diseases, wars, movements of people, and innovations constantly blurred ethnic boundaries. In the northern reaches of the Rift west of Lake Turkana, Turkana drove Maa-speakers south and east of the lake where they settled as Samburu cattle herders alongside unrelated Rendille camel herders, some of the two later combining as Ariaal.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Being MaasaiEthnicity and Identity in East Africa, pp. 1 - 18Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 1993