In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Margot Kidder was one of the world’s most popular actresses, having played the female lead in the box office smash Superman, as well as a series of other popular and critically acclaimed films. In April 1996, however, Kidder’s life and career were in a totally different place, as she wandered and slept in the streets of downtown Los Angeles in terror, believing that her ex-husband was trying to kill her. Though Kidder had the financial means to sleep elsewhere, she was led to the street through a series of apparently irrational actions. People magazine reported:

In the early hours of April 21, she tried to take a taxi but didn’t have enough money for the trip. She tried to use her ATM card outside the airport but thought the cash machine was about to explode. “I took off running,” Kidder recalls. “I slept in yards and on porches in a state of fear.”Reference Reed1

After four days of wandering and being out of touch with her family, Kidder eventually sought help from a stranger, who contacted the police. After a brief hospitalization, she was reunited with her family and her life began to return to normal. Since this widely publicized incident, Kidder has spoken about having bipolar disorder, which is consistent with the characterization of her behavior as being the result of a manic episode with psychotic features.

By 2012, Kidder was still in the public eye and had continued to work as an actor (though with less frequency than before); however, she stated that in many ways the general public had not been able to get past the 1996 incident. Railing against the view that people often have about the words “mental illness” and the perception that it is a permanent and irrevocable condition, she stated: “[I]f I were a cancer patient, I would today be considered cured – I haven’t had an episode in 14 years.”2

While Margot Kidder’s apparent psychotic episode was reported in the news, it occurred prior to the age of social media, which allows celebrities to directly communicate with their fans and others. Actress Amanda Bynes, who rose to celebrity as the teenaged star of shows on the TV channel Nickelodeon, came into contact with the implications of this type of communication in 2014, when she used her Twitter account (which reached more than 3 million followers) to accuse her father of sexual abuse, before retracting the statement with the post: “My dad never did any of those things/ The microchip in my brain made me say those things but he’s the one that ordered them to microchip me.”Reference McNiece3 This statement and a series of odd public incidents were widely reported. Public comments to internet-based articles indicated that while some members of the general public were concerned, others were delighted. Examples of comments to one article included: “She’s cute for a nutjob,” and “another vapid, clueless, selfish, insane celebrity demonstrating what happens when she doesn’t take her medications.”4 After an involuntary hospitalization, Bynes withdrew from the public eye, although she subsequently announced, via Twitter, that she had bipolar disorder and was receiving treatment for it. At the time of this writing, she is enrolled as a student at the University of Southern California, and is described by Wikipedia as a “former actress.”5 It remains to be seen what direction her young life will take, and the impact that her apparent public demonstration of the symptoms of mental illness will have on its direction.

Although the two presented examples concern famous actors, most people who experience episodes of what is usually called mental illness live far from the world of Hollywood celebrity. Jose (actual name and other identifying information have been changed) is a thoughtful man in his early thirties with a college degree. He is well read and a talented writer of prose and poetry who has also experienced a number of episodes where he acted bizarrely (e.g., walking the streets of New York City at night singing loudly) and reported having visions he interpreted as coming from God. These episodes invariably led to hospitalization, and he has been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. Not having experienced any such symptoms for more than a year, Jose desperately wants to work, engage in a spiritual community, and have a romantic relationship, but is terrified of entering social situations where he might be asked questions about his life that could lead others to find out about his psychiatric history. As a result, he avoids entering new social situations (including going to religious services) that could provide him with the opportunity to meet new people. Although he regularly looks for work, he often does not apply for jobs that look interesting or are in his area of expertise because he is overcome by thoughts that he is not capable of doing more than a service-sector job as a result of his history of mental illness. He also struggles with the belief that he is a failure and intermittently has thoughts of suicide.

From Labeling Behavior to Labeling People

What do the examples in the preceding section have in common? Although they all concern situations in which individuals with other talents and attributes have engaged in behavior that was explained as being the result of a mental illness, they also concern the long-standing implications of others’ judgments of these behavioral instances. If we pay close attention, a series of processes are occurring. First, the instance of unusual behavior leads to labeling (e.g., Amanda Bynes goes from being a starlet to a “nutjob” or “insane”). The label, which is linked to certain assumptions, then sticks and affects people’s impressions of the individuals’ behavior, even when they are not demonstrating any signs of unusual behavior (e.g., Margot Kidder’s experiencing that she was still thought of as mentally ill when she had not had an episode in more than 14 years). Furthermore, we see the individuals’ social behavior and self-image being affected by their awareness of others’ labeling (e.g., Jose’s belief that he is a failure and his related avoidance of social situations that he is interested and capable of engaging in).

All of these processes are tied to an idea that is most often called stigma. Although other terms capture aspects of what is going on (stereotyping, discrimination, social rejection, shame, etc.), stigma has served as a useful umbrella term for the overall process. The word has origins in ancient Greek (referring to the practice of branding or otherwise mutilating an individual to show that he or she is a member of a morally discredited group), but modern usageFootnote a, Reference Link, Stuart, Gaebel, Rossler and Sartorius6 of the term is usually linked to sociologist Erving Goffman’s 1963 book Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity.Reference Goffman7 In this influential work, Goffman described how stigma impacts people from a number of social categories, but paid repeated attention to the experience of people who have been diagnosed with mental illness, whom he referred to as “ex-mental patients.” Goffman specifically discussed how stigma impacts ex-mental patients by making them not just “discredited,” but “discreditable” in their social interactions. Discredited interactions are ones where others are aware of the person’s psychiatric history and are therefore biased by this awareness (we may think of overt discrimination or social rejection as instances of this). However, discreditable interactions can be even more pernicious. In this case, the ex-mental patient interacts with others who have no knowledge of his or her history (and therefore do not prejudge him or her) but lives in fear of them finding out, and therefore “discrediting” whatever positive impressions he or she is able to make. As Goffman stated: “By intention or in effect the ex-mental patient conceals information about his real social identity, receiving and accepting treatment [from others] based on false suppositions concerning himself.”Reference Goffman7

A key part of the stigma process, which was implied by Goffman but that is not always made clear, is that members of society go from labeling a specific instance of behavior (e.g., acting oddly = psychotic episode) to labeling a person (person who has ever acted oddly = “a mentally ill person”). That label is then attached to a series of assumptions, or “negative stereotypes,” about what a person with that label is like and will continue to be like. As we’ll see, the most commonly endorsed negative stereotypes about mental illness include beliefs that the person is dangerous, unpredictable, incompetent, and unable to function in society.Reference Corrigan and Penn8 As Goffman indicated, this means that future actions that the individual takes, regardless of how reasonable they are, can be viewed through the lens of this label, and therefore discredited, or “written off.”Footnote b Thus, there is a movement from discrediting actions performed by people to discrediting the people themselves. The experience of being aware that one has been discredited then has a profound impact on the person’s social behavior and self-image.

In this book, I will explain in detail what we know about this process from more than five decades of research. First, however, I will clarify what types of psychiatric experiences are most likely to result in stigma and provide some general information about these experiences.

What Are We Talking about When We Say “Mental Illness”?

Not all constellations of behavior and internal experiences that can be categorized as psychiatric disorders are necessarily linked to significant stigma. The diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association (the current edition is called the DSM-5) catalogues a number of constellations of experiences that are considered “mental disorders,” including relatively minor conditions such as specific phobias (e.g., fears of snakes or spiders) and short-lived mood disturbances called adjustment disorders. Based on the best estimates from population surveys in the United States, roughly 25% of the US population meets criteria for a DSM disorder at any given time, while roughly 45–50% of the population experiences a disorder at some point in life.Reference Kessler9 The most common mental disorders in the United States include specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, and alcohol use disorder. The reader may intuitively recognize that, given how common mental disorders are, it is not plausible for all constellations of experiences meeting technical criteria for “mental illness” to be subject to equal amounts of stigma. In fact, this is supported by research findings, which indicate that it is a subset of mental disorders, often called “severe mental illnesses,” which are most subject to stigma.Reference Wood10 “Severe mental illnesses” are usually defined as consisting of mental disorders that have a substantial impact on functioning (employment, relationships, etc.) and/or lead to hospitalization.Reference Ruggeri, Leese, Thornicroft, Bisoffi and Tansella11 Research is fairly consistent in finding that roughly 5–7% of the US population meet criteria for a severe mental illness. Although not a diagnostic category, the concept of severe mental illness has been found to be useful among policymakers in determining who to prioritize for funding and high intensity services.

What characteristics do the disorders that can be classified as “severe” have? Although there are no definitive diagnostic criteria, a frequent element is the experience of “psychotic” symptoms that often lead to psychiatric hospitalization. Psychotic symptoms include experiences such as delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized (or illogical) thinking, and involve, as a common theme, a disruption in one’s perception of reality. A person who is experiencing psychotic symptoms may not be sure about what is and is not real, and, like Margot Kidder in the prior example, may act in ways that do not make sense to others. In another age, these were the experiences that were most likely to lead to the characterization that one was “mad” or “insane.” Although psychotic symptoms can occur in a number of disorders, they are most often associated with two conditions: schizophrenia (and other disorders in its “spectrum” such as schizoaffective disorder), which is defined by the presence of psychotic symptoms, and bipolar 1 disorder, which is commonly characterized by psychotic symptoms during “manic” episodes. Both of these disorders are relatively rare, occurring in roughly 1–2% of the population each.Reference Kessler12

It is important to note that, while both schizophrenia and bipolar 1 disorder are “persistent” disorders (meaning that they tend to be a recurring part of one’s life for a long time after symptoms are first experienced), it is also clear that they are typically “episodic” (meaning that intense symptoms come and go in waves that vary in length, from just a few days to many months).Reference Judd13 It has been estimated that people with severe mental illnesses typically spend only 5% of their lives in states of “acute” distress (where intense symptoms are being experienced), meaning that the vast majority of the time they are not likely to be demonstrating overt symptoms.Reference Davidson, Rakfeldt and Strauss14 It is also important to note that, while these disorders, by definition, have a substantial impact on functioning (including work and social relationships), evidence supports that, when followed-up 20 or more years after the initial experience of symptoms, roughly one-half to two-thirds of them show minimal impairment in their life functioning.Reference Calabrese, Corrigan, Ralph and Corrigan15 Thus, people tend to improve in their life functioning over time, although the process of improvement sometimes takes decades.

Psychotic Symptoms: Part of the Human Experience?

As indicated above, diagnosable disorders that feature psychotic symptoms are rare, and there is an inherent assumption that they lie outside of the everyday range of human experience. However, although disorders that require that one experience psychotic symptoms that interfere with functioning are rare, psychotic experiences themselves are considerably less so. Community surveys have investigated the prevalence of psychotic experiences (e.g., transitory experiences of auditory hallucinations or beliefs that one is being persecuted) in the general population around the world and have consistently found that close to 10% of the general population reports having had psychotic experiences, with some large studies reporting estimates as high as roughly 20%.Reference Van Os, Linscott, Myin-Germeys, Delespual and Krabbendam16 Clearly, the majority of these individuals did not develop a psychotic disorder (meaning that the experiences were not frequent enough and/or never interfered with functioning), although it is plausible to think that they might be at a higher “risk” for developing such a disorder under the right conditions. However, in most cases the experiences lead to nothing further.Footnote c, Reference Rossler, Riecher-Rossler, Angst, Murray, Gamma, Eich, Van Os and Gross17 An example of the experience of psychotic symptoms not interfering with functioning is provided by Sigmund Freud, the “father” of psychoanalysis and modern psychotherapy, who revealed that he had hallucinatory experiences as a young man:

During the days when I was living alone in a foreign city – I was a young man at the time – I quite often [emphasis added] heard my name suddenly called by an unmistakable and beloved voice; I then noted down the exact moment of the hallucination and made anxious enquiries of those at home about what had happened at that time. Nothing had happened.Reference Sacks18

Mahatma Gandhi, who discussed hearing the “voice of God” at key instances in his life, provides another example of hallucinations not interfering with functioning. Describing the “voice,” he stated:

Could I give any further evidence that it was truly the Voice that I heard and that it was not an echo of my own heated imagination? I have no further evidence to convince the skeptic. He is free to say that it was all self-delusion or hallucination. It may well have been so. I can offer no proof to the contrary. But I can say this, that not the unanimous verdict of the whole world against me could shake me from the belief that what I heard was the true Voice of God.19

In addition to the extent to which psychotic experiences are relatively common, it has also been asserted that some of the cognitive processes involved in developing delusions reflect exaggerations of basic human cognitive processes. In his book The Storytelling Animal, writer Jonathan Gottschall compellingly argues that the cognitive process involved in developing delusions is related to the fundamental, and usually healthy, human tendency to “make a coherent story” out of the chaos of information that the universe provides us with. This has been confirmed in experimental studies where people are presented with a list of unrelated events and are found to seek to connect them with a narrative thread that has its own internal logic. The human mind abhors coincidences. Sometimes, however, this leads people to want to make a coherent story out of a confusing situation, even when the resulting tale has no basis in fact. As an example, Gottschall points to the popularity of conspiracy theories that lack any evidence, but that help people make sense of confusing or distressing events since they explain them in such a tidy manner. Notably, poll research found that at one time roughly a third of the US population endorsed the view that the US government was involved in a conspiracy that caused the September 11, 2001 attacks.Reference Gottschall20 Readers will likely also be familiar with other, more recent, examples of the widespread belief in conspiracy theories propagated by “fake news” internet sources.

A related line of thought has concerned the tendency for many people to “jump to conclusions,” or draw hasty conclusions from incomplete information. A “jumping to conclusions” tendency has been found to be very common among people who develop delusions (occurring in about 50% of such individuals), but to also be common in the general population (occurring in about 20% of nonclinical samples).Reference Freeman, Pugh and Garety21 Research has found that individuals who show the “jumping to conclusions” bias are more likely to show evidence of subclinical paranoid ideation (i.e., general suspiciousness) and have odd perceptual experiences, despite not meeting the criteria for any psychotic disorder.

Given this evidence, it has been hypothesized that anyone, under the right circumstances (especially if we include the use of mind-altering substances), might have the capacity to develop psychotic symptoms, though some people certainly seem to have a greater propensity to develop them than others. This hypothesis is impossible to ethically test, but there is no reason to dismiss it out of hand, given evidence that psychotic experiences are related to imbalances in neurotransmitters that all humans possess. The theory that “anyone can experience psychosis” became real to my family when my father, a psychiatrist who had spent much of his career treating psychotic symptoms, began to experience visual hallucinations late in life after experiencing a cerebral stroke.

One might think that, given the degree to which psychotic experiences and other forms of irrationality are a potentially common part of the human experience, people would react to them with empathy rather than judgment or aversion. This certainly makes superficial sense, but, as is the case with other stigmatized attributes in human society, things do not always work that way. For example, given evidence that attraction to members of the same sex is to some degree normative in human society,Reference Dickson, Paul and Herbison22 one might think that homosexuality would not be stigmatized, but this has been far from the truth for much of human history. Or, consider how being significantly overweight is stigmatized even though concern about weight and struggles with weight-control are so common.

Does Stigma Really Make a Difference?

Even if they acknowledge that mental health stigma exists (which I will demonstrate in the next chapter), many readers will certainly question whether it really makes that much of a difference in the lives of people who have been diagnosed with a severe mental illness, given that mental illness symptoms have a great impact themselves. It was not stigma, they may reason, that led Margot Kidder to the streets of Los Angeles, but the symptoms of an untreated mental disorder. This is a valid consideration, and, in large part, it will be the task of this book to persuade readers that the balance of the evidence indicates that stigma has a measurable impact on the lives of people diagnosed with severe mental illness above and beyond the direct impact of symptoms themselves. However, this does not mean that the impact of stigma cannot be overstated.

In the 1960s, this occurred when some researchers had become adherents of “labeling theory,” which argued that most or all of the behavior that is associated with what is called mental illness is the result of the person having been so labeled.Reference Gove and Gove23 The actual behavior that led to the label being applied was largely beside the point, according to this view. Although, as we’ll see, some aspects of labeling theory are supported by research evidence, the more extreme version of this theory did not hold up to empirical tests. As a result, there was a backlash against any assertions that stigma mattered in the 1970s and early 1980s. In 1982, Walter Gove declared labeling theory dead and stated “in the vast majority of cases the stigma [of mental illness] appears to be transitory and does not appear to pose a severe problem.”Reference Gove and Gove23 Guido Crocetti and colleagues went further and argued that, in addition to there being very little evidence for stigmatizing attitudes or behavior in the general public, it was, rather, “the belief [emphasis added] that stigma is attached to mental hospitalization” that was “potentially harmful and dangerous,” because it led people to avoid treatment out of fear of becoming stigmatized.Reference Crocetti, Spiro and Siassi24

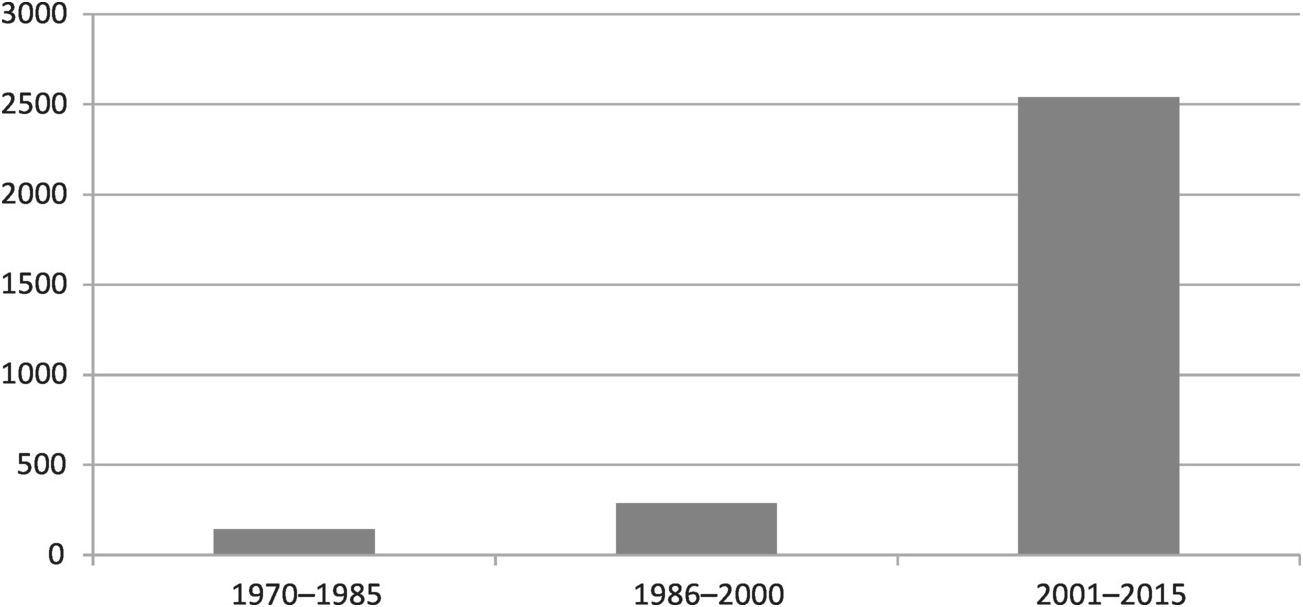

These views were influential, and scientific interest in stigma was minimal between 1970 and 1985 (see Figure 1). This changed with the publication of articles by researcher Bruce Link in the late 1980s, which revived interest in the topic (we will learn more about the implications of his research in Chapter 5).

Figure 1 Articles in peer-reviewed journals on “mental illness” and “stigma” or “labeling,” by 15-year period

In the most recent period, as Figure 1 makes clear, there has been a dramatically increased interest in stigma. This has been reflected in official interest from institutions affiliated with the US government. However, the focus is not usually on the aspects of the stigma process that will be emphasized in this book. Rather, the typical focus is on the problems posed by stigma as a barrier to seeking help. For example, in 1999, during the Clinton administration, the US Surgeon General published a report on mental health that paid a great deal of attention to stigma, but its main focus was on the impact of stigma on seeking treatment.25 Similarly, in the Bush administration’s 2003 President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health report, stigma was prominently discussed, but with an emphasis on how it interferes with seeking treatment (one of the report’s main recommendations was “advance and implement a national campaign to reduce the stigma of seeking care”).26 President Obama was no different, convening a National Conference on Mental Health in 2013, and issuing the following statement on the importance of stigma:

We’ve got to get rid of that embarrassment; we’ve got to get rid of that stigma. Too many Americans who struggle with mental health illnesses are still suffering in silence rather than seeking help, and we need to see it that men and women who would never hesitate to go see a doctor if they had a broken arm or came down with the flu, that they have that same attitude when it comes to their mental health.27

People avoid seeking treatment because of concern about stigma, the logic goes; if stigma were reduced, they would seek treatment. A corollary of this view is the contention that, if people can only seek treatment, symptoms will decrease and stigma will go away.Reference Lillienfield, Smith, Watts, Craighead, Miklowitz and Craighead28

This emphasis is well-intentioned, but although the association between stigma and help-seeking is certainly important, it is not, I will demonstrate, the main reason why stigma is a major issue. Rather, the main reason why stigma is important is because it diminishes people’s participation in community life, and inhibits them from achieving their full potential as people. As a result, all of society suffers from the loss of these individuals’ potential contributions to their communities. Stigma, I will show, would persist even if everyone with a diagnosable mental disorder received treatment, and, in some respects, treatment can make stigma worse if it is not implemented properly.

Mental Health Stigma: A Social Justice Issue

Therefore, instead of viewing mental health stigma as a help-seeking issue, we should view it as a social justice issue. As this book will demonstrate, mental health stigma is linked to substantially diminished opportunities for full community participation among people diagnosed with severe mental illnesses. As Patrick Corrigan and others have argued,Reference Corrigan and Corrigan29 viewing stigma from a social justice perspective requires that we move away from just focusing on eradicating symptoms, and instead focus on the negative social reaction to them. In this manner, the effort to overcome the effects of stigma can be linked to other social movements that have sought (with some success) to reduce the social marginalization of people from a number of backgrounds, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons, physically disabled persons, and members of derogated racial and ethnic groups.

Taking a step further, when we think of the importance of mental health stigma, it is helpful to break out of the mindset that we are thinking about something that relates to a small but important subgroup in human society, and replace it with the view that we are thinking about something that relates to a small but important part of ourselves as humans. This makes sense when we adopt the mindset that psychotic and related experiences associated with mental illness can happen to anyone, meaning that stigma is a potential problem for all of members of society. In fact, although most people develop them as young adults, a substantial proportion (roughly 20% according to most estimates) of persons who develop schizophrenia and bipolar disorder develop these disorders after age 40.Reference Pearman and Batra30 Thus, though most choose not to acknowledge it, even if one has no mental illness at present, few can be certain of whether or not they will have a severe mental illness sometime in the future. As Judi Chamberlain stated in her 1978 classic On Our Own, because of the stigma attached to the label of mental illness, “we are all rendered a little less human.” Going further, she stated: “This is a problem not just for patients and ex-patients but for everyone, because anyone can become a mental patient.”Reference Chamberlain31

In A Theory of Justice, political philosopher John Rawls argued that, in order to determine what is just, we should do so from the perspective of the “Original Position,” in which none of us knows in advance which position we will occupy in society.Reference Rawls32 None of us would choose to live in a society in which being born a woman, African-American, or gay leads to systematic social exclusion or diminished opportunity, if we knew that it was possible that we might inhabit one of those categories ourselves. This perspective makes it clear that inequities based on inherited statuses such as gender, race, and sexual orientation would be universally agreed-upon to be unjust if all were able to view them from the Original Position. If we extend this perspective to the experience of a severe mental illness (which most would agree is a status that is largely the result of forces beyond an individual’s control), it becomes clear that stigma and its related effects on full community participation are a social justice issue. Theoretically, no one would choose to live in a society in which having a severe mental illness leads to de facto marginalization, if it was known that they might have a mental illness themselves.

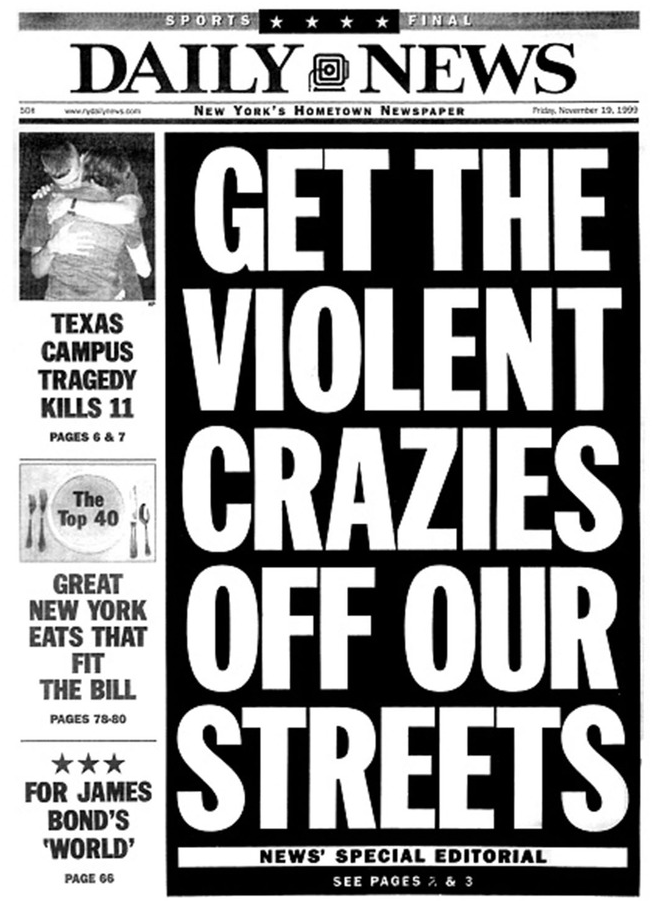

This perspective rings especially true if we are able to put ourselves in the position of people who have been diagnosed with mental illnesses and imagine how we might feel when confronted with a newspaper headline like the one shown above (see Figure 2). Can we imagine an equivalent derogatory term for another group appearing in such a manner on the front page of a major US newspaper, with no measurable outcry as a result? As noted psychologist (who has also spoken about her experience with bipolar disorder) Kay Jamison has stated: “Newspapers and television stations can print and broadcast statements about those with mental illness that would simply not be tolerated if they were said about any other minority group.”Reference Jamison33 Indeed, we are all rendered less human when these types of headlines not only appear but are tolerated. And this is indicative of only the loudest and most public expressions of stigma; there are many more person-to-person expressions of stigma that do not make it to the “headline” level but that can be even more hurtful to those that hear them, as we will learn in subsequent chapters.

Figure 2 A newspaper headline in New York City in 1999, following a random violent incident that was committed by a man subsequently found to have no evidence of mental illness.

The sometimes frightening experiences that we call mental illness are not just a social construction – they are very real. However, stigma makes a difficult and challenging part of the human experience much worse, as we move from discrediting actions to discrediting people, and as the discrediting views of others come to be internalized by those who have been diagnosed with a mental illness. In this book, we will learn how this occurs, and will also begin to look toward ways to imagine a future where experiencing mental illness no longer leads to this process.