1. Introduction

In the summer months of 2010, a national language policy drama unfolded in Norway. The country’s largest company measured by revenue, Statoil ASA (now Equinor ASA) decided to implement English as their common corporate language. For a company present in 36 countries (Equinor 2018), the use of a common language could significantly reduce the need for translation and interpretation. Increased globalisation and cooperation across national and linguistic borders have led a number of multinational corporations (MNCs) in the Nordic region to adopt similar English-only policies (Luo & Shenkar Reference Luo and Shenkar2006, Piekkari, Welch & Welch Reference Welch and Welch2014).

But in the case of Statoil/Equinor, the company’s partners and suppliers in Norway were not in agreement with the new language policy. Ultimately, the Norwegian Minister of Petroleum and Energy, Terje Riis-Johansen, got involved, and Statoil, at the time, was forced to abandon their English-only policy (Riis-Johansen Reference Riis-Johansen2010). This complete turnaround came after the Norwegian government advisory body on language issues Språkrådet [the Language Council of Norway] pointed out in an open letter to Riis-Johansen (Språkrådet 2010a) that Statoil’s practice was contrary to the government’s language policy platform embodied in Report no. 35 (2007–2008) ‘Mål og meining. Ein heilskapeleg norsk språkpolitikk’ [Language and meaning: A holistic Norwegian language policy], commonly referred to as ‘the language report’ (Kultur- og kirkedepartementet 2008). As one of the most important players in the Norwegian economy, Statoil’s abandonment of Norwegian was not consistent with the language policy goal of the Norwegian state, according to the Language Council, namely ‘to ensure the status of Norwegian and its use in all parts of the Norwegian society’Footnote 1 (Språkrådet 2010b).

The Statoil/Equinor case shows that the language practices of a firm can be wide-ranging, and involve the interests of multiple individuals and groups of people. When key industry players choose to communicate in languages other than the national language, for example, by implementing company-specific language policies, their decisions will also affect parties outside the firm.

The purpose of this study is to examine how the official language policy of the Norwegian state manifests itself in the country’s corporate legislation, and more importantly, the extent to which companies in Norway comply with legal provisions concerning language use. By adopting a legal perspective on the country’s language policy, as it has been stipulated by the Ministry of Culture and Church (Kultur- og kirkedepartementet 2008), and the Language Council of Norway (Språkrådet 2005), the paper discusses compliance with the language policy from the perspective of the Norwegian authorities. The discussion will focus on one specific legal provision, namely the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act Article 3-4. By doing so, the paper seeks to answer the following research question: Do companies in Norway comply with the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act, and if not, why?

The case of language policy and corporate law in Norway demonstrates how the regulatory framework of a country may affect the linguistic-communicative behaviour of MNCs and domestic firms by imposing regulations for language use. This multidisciplinary perspective allows for a contextual analysis of company-specific language policies which contributes to ongoing debates about language practices within sociolinguistics, corporate law and language-sensitive research in international business.

2. Language and business: Theoretical and contextual framework

This section will present the theoretical and contextual framework for the present study. The section is divided into three subsections. Section 2.1 focuses on existing literature and previous studies on the role of language in international business. Section 2.2 presents an overview of theories and concepts related to multilingualism in modern societies, specifically the use of language regulation, language policies and language laws. Finally, Section 2.3 gives an introduction to the research setting of the study, namely the use of language in Norwegian business.

2.1 Language in international business

The importance of language in and for international business has been established in a number of publications in recent years (see Piekkari & Zander Reference Zander2005, Piekkari & Tietze Reference Tietze2011, Brannen, Piekkari & Tietze Reference Brannen, Piekkari and Tietze2014, Sanden Reference Sanden2016a). The pioneering work in this field, such as Marschan, Welch & Welch (Reference Marschan [Marschan-Piekkari], Welch and Welch1997), Marschan-Piekkari, Welch & Welch (Reference Marschan-Piekkari, Welch and Welch1999a, b), Feely & Harzing (Reference Feely and Harzing2003) and Harzing & Feely (Reference Harzing and Feely2008) has demonstrated how language influences all types of business organisations. Multinational corporations are particularly likely to encounter issues related to multilingualism and linguistic diversity. As argued by Piekkari et al. (Reference Welch and Welch2014:218), one of the main challenges for multilingual organisations is finding a way to accommodate the various requirements of the different subsidiary contexts, especially when there are country-specific legislations that dictate the use of the local language.

A common corporate language, e.g. English, can in some cases offer certain benefits to companies struggling to manage linguistic diversity. Numerous empirical studies within language-sensitive research in international business examine the consequences of such language policies (e.g. Marschan-Piekkari, Welch & Welch Reference Marschan-Piekkari, Welch and Welch1999a, Reference Marschan-Piekkari, Welch and Welch1999b; Vaara et al. Reference Vaara, Tienari, Piekkari [Marschan-Piekkari] and Säntti2005; Fredriksson, Barner-Rasmussen & Piekkari Reference Fredriksson, Barner-Rasmussen and Piekkari2006; Neeley Reference Neeley2013, Reference Neeley2017; Sanden & Kankaanranta Reference Sanden and Kankaanranta2018; Sanden & Lønsmann Reference Sanden and Lønsmann2018). One of the most comprehensive studies in this field is Neeley’s (Reference Neeley2017) longitudinal study of the Japanese online retailer Rakuten and its English-only policy. Although the shift to English was seen as very controversial at the beginning, the language policy allowed for accelerated international expansion and increased knowledge sharing across geographically dispersed organisational units, according to the author. While the use of a common language may facilitate smoother and faster exchange of information as it did in the case of Rakuten, a lingua franca is rarely the solution to all communicative problems, as discussed by Sanden (Reference Sanden2020). Multilingualism is often part of the daily work life for many employees (Nelson Reference Nelson2014), and they can find it difficult to communicate in accordance with the firm’s official language policy (Sanden & Lønsmann Reference Sanden and Lønsmann2018). Previous research has shown that English-only policies can lead to problems such as status loss and decreased employee performance (Neeley Reference Neeley2013), exclusion and discrimination (Charles & Marschan-Piekkari Reference Charles and Marschan-Piekkari2002), and reallocation of power due to individual language skills (Piekkari et al. Reference Vaara, Tienari and Säntti2005, Vaara et al. Reference Vaara, Tienari, Piekkari [Marschan-Piekkari] and Säntti2005).

The widespread use of English business communication in non-native English-speaking countries also has implications for financial reporting. Financial statements, which are often presented as annual reports, are in many cases an important source of information about a company’s financial situation, the company’s activities, and other circumstances surrounding its operations. In addition to disclosing information about the company’s current fiscal year, annual reports usually contain information about the company’s strategic direction and future goals. Financial statements can therefore have a variety of audiences, including everyone from the company’s owners, investors, creditors, suppliers and partners, to employees, and residents of the community where the company operates (Skattedirektoratet 2012). These groups may have different language requirements which are important to take into consideration when producing the financial statements.

As discussed in Jeanjean, Lesage & Stolowy’s (Reference Jeanjean, Lesage and Stolowy2010) study of language choice in annual reports, the use of English allows firms to reach potential investors outside their home market, thereby increasing the size of their investor base. This is commonly referred to as the investor base hypothesis or the awareness hypothesis. However, Jeanjean et al. (Reference Jeanjean, Lesage and Stolowy2010:205) argue that there are both direct and indirect costs associated with producing annual reports in English: ‘When a company publishes an English annual report, it probably widens its investor base but is potentially at risk of sending out a less articulate message to its English-speaking investors’. Research on the communication of financial information across national borders provides insight into the particular problem of annual reports. Kettunen (Reference Kettunen2017:38) explains that it is often difficult to find a word-for-word equivalence when translating accounting terminology. Having interviewed 12 Finnish translators, Kettunen observes that the translators sometimes invent new accounting terminology in Finnish for financial instruments and company forms that do not exist in Finland. According to Evans, Baskerville & Nara (Reference Evans, Baskerville and Nara2015), ‘the main cause of translation difficulties lies in the fact that different languages do not represent the same social reality’. This is particularly problematic when communication serves specific purposes, as exemplified by the translation of accounting terminology.

2.2 Multilingualism and language regulation

The implementation of English as a common corporate language is often portrayed as contributing to a ‘domain loss’ in Norwegian business (and Scandinavia in general, see e.g. Lønsmann Reference Lønsmann2011). Kristiansen (Reference Kristiansen2012:88) defines domain loss as ‘a process that begins when Norwegian terms no longer are developed within certain subject areas’.Footnote 2 Kristiansen’s definition is similar to the definition adopted by the Language Council of Norway in their language policy document ‘Norsk i hundre! Norsk som nasjonalspråk i globaliseringens tidsalder’ [Norwegian at full speed! Norwegian as the national language in the age of globalisation] (Språkrådet 2005). In this report (ibid.:15) domain loss is defined as ‘a development where English (or another foreign language) replaces Norwegian within a particular domain…. When Norwegian is no longer used within the domain, the domain loss is a fact’.Footnote 3

However, what the domain loss literature fails to fully acknowledge, is the fact that multilingualism is a natural part of most modern societies. As argued by e.g. Archibugi (Reference Archibugi2005), Dor (Reference Dor2004) and Duchêne (Reference Duchêne2009), increased economic and social globalisation does not necessarily imply loss of the local language. There are in other words conflicting views on the effects that globalisation has on multilingualism. As pointed out by Grin, Sfreddo & Vaillancourt (Reference Grin, Sfreddo and Vaillancourt2010:12) some scholars believe linguistic diversity is increasing as a result of more international contact in the form of globalisation, while others believe globalisations erodes multilingualism by promoting the use of one hegemonic language. Empirical evidence demonstrates that there is some truth to both of these hypotheses, and that language practices in real-life situations are complex, overlapping and constantly changing (García & Wei Reference García and Wei2018). Other scholars, like Hornberger (Reference Hornberger2002), Baldauf (Reference Baldauf2012), King & Rambow (Reference King, Rambow and Spolsky2012) and Réaume & Pinto (Reference Réaume, Pinto and Spolsky2012), question the significance of globalisation altogether, and argue that the tension between monolingualism and multilingualism is far from a new phenomenon. Réaume & Pinto (Reference Réaume, Pinto and Spolsky2012:57), for example, discuss that the arguments used either for or against multilingualism have remained constant since the early 19th century. Today’s debate only repeats the arguments in ‘twenty-first century vernacular’ (ibid.)

Although it is important to be aware of these different perspectives, it is fair to note that increased international trade has implications for language use, and that we are witnessing some of these implications today. In the context of this study, there are two situations of particular importance: (i) when different languages in a multilingual domain are assigned different statuses by the language users internal to the domain, which is a phenomenon called diglossia (Ferguson Reference Ferguson1959); and (ii) when a domain loss over time causes a language to die out, which is commonly referred to as language death (Fishman Reference Fishman2001).

However, history has shown that multilingual societies can remain stable and well-functioning over time (Boyd Reference Boyd, Norrby and Hajek2011; Josephson Reference Josephson2018:105–106). The existence of a high status language does not in itself imply that the lower status language will disappear. The potentially negative consequences of diglossia, such as language discrimination, can be prevented through different forms of language regulation, such as language policies and language legislation.

‘Language policy’ is a broad term that denotes all forms of language control. Kaplan & Baldauf (Reference Kaplan and Baldauf1997), for example, discuss how language policies include the regulations, rules, practices, or body of ideas intended to achieve a planned language change in a society, group, or system. Following a review of the language policy literature, Sanden & Kankaanranta (Reference Sanden and Kankaanranta2018:547) conclude that ‘the term “language policy” may encompass a wide range of phenomena: from formal/formalised, official, overt, de jure language policies to informal/non-formalised, non-official, covert, de facto language policies’.

Language laws can be seen as a form of language policy in the sense that they regulate language use. Dovalil (Reference Dovalil2015:361) places language legislation within the legal system of a language community: ‘All law is related to the regulation of human behaviour. Language law regulates the segment of this behaviour that consists in language use’. The purpose of language laws is, in other words, to resolve problems that may arise in situations where different linguistic preferences prevail by legally determining the rules that govern the choice of language in these situations (Turi Reference Turi, Skutnabb-Kangas, Phillipson and Rannut1995).

The Nordic countries have approached language regulation in different ways through the use of language policies and language laws. In Norway, legal regulation of language and language use in specific domains such as business and industry is rarely discussed. This can be seen in relation to the fact that there is no general language law in Norway, which is the case in some of its neighbouring countries. Both Sweden and Finland have implemented language acts that contain provisions regarding language use within the country, as well as outlining provisions that ensure individual language rights. When Sweden passed its language act in 2009, (Språklag 2009:600; see Regeringskansliet, Sweden 2009), this was the result of an eleven-year long process that started when the Swedish Language Board in 1998 launched an action plan to reinforce the position of the Swedish language (Boyd Reference Boyd, Norrby and Hajek2011). Even though the Swedish language act aims to regulate the position of Swedish and minority languages in Sweden, it has been criticised for having a weak position in the judicial system, as it does not contain any sanctions in the case of violation (Josephson Reference Josephson2018:241).

Finland has a long tradition of language legislation due to the country’s two national languages, Finnish and Swedish. When the current Finnish language act (Språklag 6.6.2003/423) came into force on 1 January 2004, it replaced the country’s old language act from 1922 (see Finlex, Finland 2017). The Finnish language act confirms the rights of the Swedish-speaking minority, and provides detailed instructions on how to manage the country’s bilingualism in various situations (Tavvitsainen & Pahta Reference Tavvitsainen and Pahta2003).

Unlike Sweden and Finland, but similar to Norway, Denmark has not issued any national regulation regarding language use. Of the Nordic countries, Denmark can be described as the most laissez-faire one in terms of language regulation, and not without criticism (see e.g. Siiner Reference Siiner2010). In the Nordic context, Norway has therefore done more than Denmark by addressing language-related issues through the means of its official language policy, although the principles stipulated in the Norwegian language policy have not been ratified by a general law, as in the case of Sweden and Finland. The following section takes a closer look at the language policy situation in Norway, with a particular focus on the role of English in Norwegian business.

2.3 Research setting: The Norwegian context

The Norwegian economy is small, and Norway is largely dependent on international trade. Norway’s major export products are oil and gas (which account for 50% of the country’s total export), machinery and mechanical-engineering products (14% of total export) and fish and fish products (8% of total export). The majority of export and import activity to and from Norway takes place between Norway and its neighbouring countries. The other Nordic countries, the UK and Germany are the most important trading partners (Regjeringen 2001). As the national language Norwegian is spoken by approximately five million inhabitants (Thompson Reference Thompson2016), Norwegian companies with international aspirations often find it beneficial to adopt English language policies (Sanden Reference Sanden2016a). Together with citizens in the other Scandinavian countries, Norwegians are consistently at the top of international rankings in terms of English fluency level, such as the Test of English as a Foreign Language, TOEFL (ETS 2018), and English is commonly used as a means for business communication in the Nordic region (Andersen & Rasmussen Reference Andersen and Rasmussen2004).

Increased use of English raises concerns about the uniqueness and survival of the Norwegian language (Anderman & Rogers Reference Anderman and Rogers2005a). When the Norwegian Parliament launched a committee to investigate various issues related to power and democracy in Norway (Makt- og demokratiutredningen [the Power and Democracy Investigation]), the status of the Norwegian language was one of the topics covered in the committee’s final report (Østerud et al. Reference Østerud, Engelstad, Meyer, Selle and Skjeie2003a, Østerud, Engelstad & Selle Reference Østerud, Engelstad and Selle2003b). The report examines the consequences of increased English use and assesses the risk of domain loss in Norwegian business in relation to the greater threat of language death. Makt- og demokratiutredning [the Power and Democracy Investigation] (Østerud et al. Reference Østerud, Engelstad, Meyer, Selle and Skjeie2003a:45) describes this threat as follows:

In Norway, like in many other countries, the national language is under pressure. It is influenced and replaced by Anglo-American, which is the language of globalisation. Norwegian is becoming an inferior language. This has profound consequences culturally, but also for power and democracy.Footnote 4

With reference to this statement, Østerud et al. (Reference Østerud, Engelstad, Meyer, Selle and Skjeie2003a) argue that a viable national language is imperative for a well-functioning democracy in Norway. A similar analysis of the Norwegian language can be found in the language policy report published by the Language Council of Norway (Språkrådet 2005:40). The Language Council goes even further than the Power and Democracy Investigation when outlining possible consequences of domain loss in Norway by making an explicit reference to the threat of language death (ibid.):

If Norwegian is replaced by English in central domains of Norwegian society, Norwegian is no longer a complete and fully-fledged national language. If too many domains are lost, it will in the long run not only threaten the status as the national language. It will also threaten the status of the mother tongue, and therefore the existence of the Norwegian language overall.Footnote 5

In sociolinguistic literature, lexical borrowing and language shift are two commonly mentioned reasons for domain loss (Hultgren Reference Hultgren and Linn2016; see also Anderman & Rogers Reference Anderman and Rogers2005b). As observed by Johansson & Graedler (Reference Johansson and Graedler2005), the extent of lexical borrowing from English to Norwegian is difficult to measure, as some of the loan words have been fully integrated in the Norwegian language. However, the Norwegian dictionary Bokmålsordboka gives some indication: ‘About 2200 or 3.4% of the words in Bokmålsordboka … derive from English, representing just over 10% of the total number of words derived from foreign languages’ (Johansson & Graedler Reference Johansson and Graedler2005:185). This is not a remarkable or a disturbing figure. A ‘language shift’ on the other hand, would be significantly more problematic for the Norwegian language if it involved a complete shift from Norwegian to English, as discussed by Hultgren (Reference Hultgren and Linn2016).

Although it is difficult to give a clear-cut answer to whether and to what extent the Norwegian language is losing its foothold in Norwegian business, there is strong evidence that languages other than Norwegian, and especially English, are becoming more important. An investigation of 302 Norwegian exporting companies documents the extent to which Norwegian exporting companies rely on English language communication: ‘Not only is it [English] often a working language in the firm, it is also used for 95% of the export activities, in English- as well as in non-English-speaking areas’ (Hellekjær Reference Hellekjær2012:15). Other empirical studies provide a more nuanced perspective on language use in the corporate sector as a whole. The Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise [Næringslivets Hovedorganisasjon, NHO] has, since 2014, been conducting an annual survey of competence needs among its member organisations, which includes the language needs of the organisations. The findings from NHO’s survey of 2018 (carried out by NIFU 2018) revealed that Norwegian is still considered the most important language for NHO’s members. Among the 6409 companies that took part in the survey, around 80% stated that their employees’ written and oral Norwegian skills were important for the company. English skills were considered important for 48% of NHO’s member organisations, whereas German skills were in demand by 13% of the organisations. After German, Polish skills were mentioned by 7%, and French and Spanish by 6% and 5% respectively (NIFU 2018).

The Language Council of Norway has also carried out two studies on language use in Norwegian companies, in collaboration with TNS Gallup (TNS Gallup 2015, 2016). The results indicate that both Norwegian and English are important for the companies. The first survey (TNS Gallup 2015) investigated language use in 1183 companies operating in different industry sectors. Among these companies, 99% responded that they make use of Norwegian, whereas English was used by 67% of the companies. Swedish was used by 15%, German by 8% and Danish by 8%. The second survey (TNS Gallup 2016) focused exclusively on language use in construction and industrial companies, 293 companies in total. Also here, Norwegian was used by almost all companies (98% of industrial companies and 100% of construction companies), but the use of English was more common in the industrial companies, as 83% reported using English compared to 54% of the construction companies. Instead, Swedish was used slightly more in the construction companies than in the industrial companies (22% vs. 13%). The most interesting finding from the construction and industrial companies is perhaps that 38% of the respondents believed that the use of English compromises health, safety and environment in the organisation (TNS Gallup 2016:22).

The use of two or more languages in parallel, so called parallellingual language strategies, is often seen as a way of preventing potentially negative implications of English-only language policies (Linn Reference Linn2010). As defined by Gregersen et al. (Reference Gregersen, Josephson, Huss, Holmen, Kristoffersen, Kristiansen, Östman, Londen, Hansen, Petersen, Grove, Thomassen and Bernharðsson2017:5) parallellingualism means that ‘two or more languages are used for the same purpose in a specific context or within a certain area of society’Footnote 6 (see also Kristoffersen, Kristiansen & Røyneland Reference Kristoffersen, Kristiansen, Røyneland and Gregersen2014, NHH 2017). The intention to promote the use of parallel languages in Norway, and especially in Norwegian business, is evident in the language policy documents issued by the Norwegian Ministry of Culture and Church (Kultur- og kirkedepartementet 2008) and Språkrådet (2005). Both documents state that use of parallel languages, i.e. Norwegian and English, is the most efficient strategy to combat loss of the Norwegian language. It should also be mentioned that Norway has signed the Declaration on a Nordic Language Policy, developed by the Nordic Council of Ministers (Nordic Council of Ministers 2006). The Declaration strongly encourages the use of parallel languages in the Nordic countries, which indicates that the combination of the local language and English is seen as a prevalent strategy in the region.

3. Methodology

3.1 Data collection

The data collection of this project took place in three stages. The first stage focused on identifying relevant legal provisions governing the choice of language in Norwegian corporate law. Given the lack of a general Norwegian language law, this stage involved scrutinising a large number of corporate acts to get an overview of the language requirements they put forward. The Norwegian database Lovdata (lovdata.no), which contains all current and previous legal acts and regulations in Norway, made it possible to search for language requirements in relevant acts.

The second stage of the data collection focused on gathering empirical data from companies in Norway in order to examine the extent to which these firms comply with the relevant legal provisions. Given the results from the first stage, it was decided to focus on the compliance with one particular legal provision, namely Article 3-4 of the Norwegian Accounting Act [RegnskapslovenFootnote 7]. This article regulates the language of financial statements and annual reports as follows:

Financial statements and annual reports shall be in Norwegian. The Ministry may by regulation or individual decision decide that the financial statements and/or annual reports may be in another language.Footnote 8

The purpose of the second stage was to examine the actual language practices of firms that are obliged to follow the language requirements of Norwegian legislation. In the context of this study, language practices are defined as the language used in financial reporting, i.e. the language that companies in Norway use to communicate their annual reports or financial statements. Financial statements are considered public documents in Norway according to Article 8-1 of the Accounting Act and companies are obliged to submit their financial statements to the Norwegian database Brønnøysundregistrene; it can be accessed online by the general public. Brønnøysundregistrene is a governmental agency responsible for the most important registers for private individuals and businesses in Norway. Their function is to develop and operate digital services that ‘streamline, coordinate and simplify the dialogue with the public sector’Footnote 9 (Brønnøysundregistrene 2018).

The second data collection stage involved collecting data on the language practices of the 500 largest companies in Norway measured by revenue. Every year, the Norwegian financial magazine Kapital publishes a list of the 500 largest firms in Norway, and the companies included in this ranking are commonly known as ‘the Kapital companies’ (Kapital 2016). Kapital was founded in 1971, the magazine is published twice a month, and focuses on news related to Norwegian business, the stock exchange, and financial and economic policies (Kapital 2018). Kapital’s list of the 500 largest companies measured by revenue is published in the journal’s annual summer edition. For this project, Kapital’s list for 2015 served as a guideline for gathering data on financial statements and the language in which they were written. These statements were themselves obtained through the Brønnøysundregistrene database and the companies’ websites.

The Norwegian Accounting Act Article 1-2 stipulates the criteria that determine whether a company is required to report their financial statements to the Norwegian authorities. Among the 500 Kapital companies, eight companies did not fall under these criteria, and had consequently not submitted their financial statements to the Brønnøysundregistrene database. The findings presented in this paper are therefore based on 492 financial statements.

In addition to reviewing the Kapital companies’ financial statements to find out whether these companies meet the language requirement of the Accounting Act, the research question also involves a qualitative analysis of the companies’ language practices. This part of the study will investigate companies that have received dispensation to produce their financial statements in a language other than Norwegian, i.e. English. Companies that have been granted this dispensation by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes are obliged to enclose the dispensation permit together with their (foreign language) financial statements. The dispensation permits are therefore available in the Brønnøysundregistrene database. Out of the 492 Kapital companies, 93 companies had received dispensation from the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes to produce their financial statements in English. These dispensation permits were coded and analysed as the third stage of the data analysis process.

It is important to point out that the coding of the dispensation permits only encompassed the reasons mentioned by the Directorate of Taxes, as the companies’ applications for dispensation are not publicly available. It has not been possible to analyse whether the reasons given by the companies in their application for dispensation have had any impact on the decision made by the Directorate, which is a potential limitation of the study. However, as the authority in charge, the Directorate of Taxes is the ultimate decision-maker in these cases, and they must justify on what grounds they have reached their decision. The present study aims to investigate these reasons for dispensation given by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes.

3.2 Data analysis

This study makes use of a mixed method research design. Mixed method research combines qualitative and quantitative data in an attempt to gain deeper understanding and insight into a particular phenomenon, i.e. how companies in Norway comply with the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act Article 3-4. The qualitative and quantitative data included in this study were analysed in two separate rounds, which corresponds to the compartmentalised strategy for mixed method research described by Hurmerinta & Nummela (Reference Hurmerinta, Nummela, Marschan-Piekkari and Welch2011). A compartmentalised strategy implies that the different types of data are analysed in a sequential order of methods, which means that the qualitative and quantitative data were analysed within their own tradition (Hurmerinta & Nummela Reference Hurmerinta, Nummela, Marschan-Piekkari and Welch2011:218). In the context of this project, the quantitative data collected from the 492 Kapital companies present useful background information about the companies included in this study. When presenting the results of the data analysis, key findings from the quantitative data analysis will be presented first, as these findings create a supportive basis for the findings of the qualitative analysis.

The qualitative analysis of the dispensation permits was carried out in order to reveal the grounds on which the companies have been granted dispensation by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes. A special consideration applies to companies that are listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange [Oslo Børs]. In order for companies listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange to obtain dispensation from the language requirement of the Accounting Act Article 3-4, the company must have been granted dispensation from the language requirement of the Norwegian Securities Trading Act [VerdipapirhandellovenFootnote 10] Article 5-13 (1). This article states that:

Issuers with Norway as their home state and with capital certificates listed only in the Norwegian regulated market shall give information in Norwegian.Footnote 11

Dispensation from the language requirement of the Securities Trading Act is granted by the Oslo Stock Exchange. As the findings of the quantitative analysis will show, a number of the companies included in the sample are listed on the Stock Exchange, and this requirement is therefore taken into account as part of the coding process.

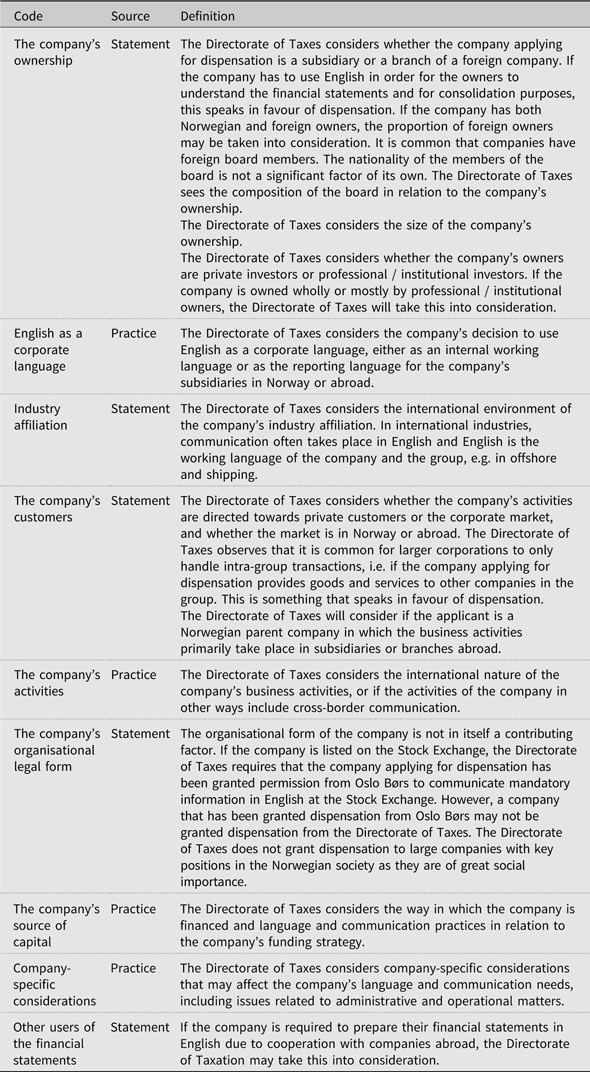

The coding of the dispensation permits was done in Microsoft Excel. The permits were analysed by content according to the principles of qualitative content analysis, and the codes emerged from two sources (see Miles & Huberman Reference Miles and Huberman1994, Corbin & Strauss Reference Corbin and Strauss2014). The first set of codes was based on a statement made by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes, where the Directorate outlines guidelines for companies that would like to apply for dispensation (Skattedirektoratet 2012). The five codes that emerged from this statement were defined by the explanation provided by the Directorate of Taxes, as shown in Table 1 below. The statements have been translated into English by the author.

Table 1. Overview of codes.

The remaining four codes were identified by the Directorate of Taxes’ dispensation practice, which is why they are referred to as ‘practice’ in Table 1. The four codes emerged when carefully analysing the dispensation permits, as it became clear that the Directorate of Taxes repeatedly referred to these reasons as relevant factors in the permits. In line with Klag & Langley’s (Reference Klag and Langley2013), discussion of ‘conceptual leaps’, the identification of the final four codes was based on a logic of discovery. An explanation of how these codes have been defined (by the author) is available in Table 1.

The nine codes were used to analyse the content of all dispensation permits. However, for two companies – TUI Norge AS (formerly Startour-Stjernereiser AS) and Visma Group Holding AS – dispensation had been granted without any explicit explanation.Footnote 12 It is therefore not possible to analyse the grounds on which the dispensation had been granted for these two companies.

The result of the analysis of the dispensation permits is presented in the findings section. It is, however, important to emphasise that the analysis has been carried out by breaking down the dispensation permits in order to identify the various elements that the Directorate of Taxes has taken into consideration in their assessment. Although these elements are dealt with individually in the findings section, it is clear that they are part of an overall evaluation of each company that has been granted dispensation. It is therefore necessary to point out that the purpose of the qualitative analysis is not to explain the grounds by which dispensation has been given for the respective companies, but rather to point out some overall trends in the data material on the basis of all dispensation permits.

The appendix contains an overview of the elements (codes) that are included in the Directorate of Taxes’ dispensation permits for each of the 93 companies. This overview also shows the occurrence of the different codes in total.

4. Findings: The Kapital companies and their language practices

This section will present findings from the Kapital companies’ language choice when reporting their financial statements to the Brønnøysundregistrene database. Before looking into the language practices of the companies, the section will present some information about key characteristics of the Kapital companies.

4.1 The Kapital companies: Background information

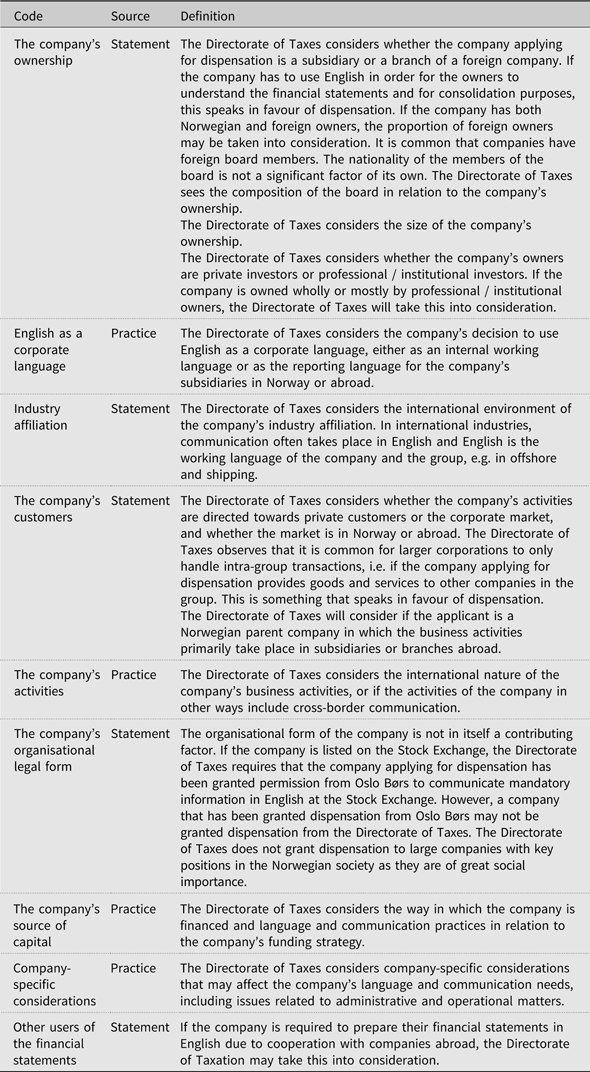

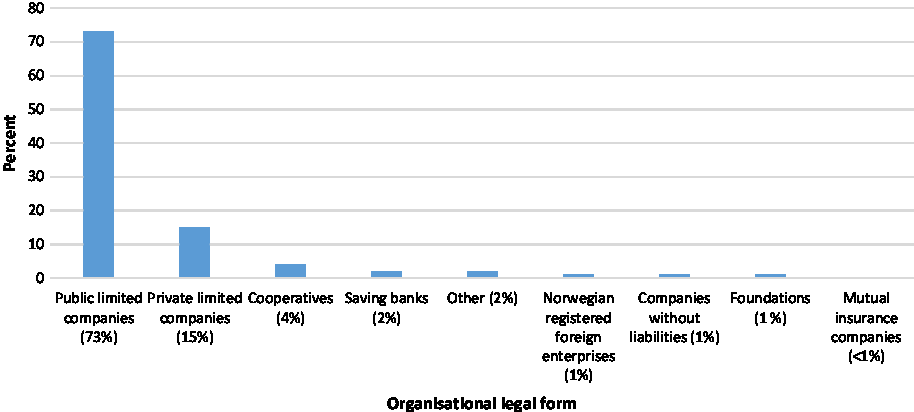

Figure 1 shows the industry affiliation of the Kapital companies, according to the Kapital ranking (Kapital 2016). The retail and industrial sectors are the two most common, as 19% and 16% of the companies operate within these industry sectors respectively. Still, as is evident from Figure 1, the Kapital companies operate within a wide range of industry sectors, indicating that they constitute a heterogeneous mix of firms.

Figure 1. Industry affiliation of the Kapital companies (in percent).

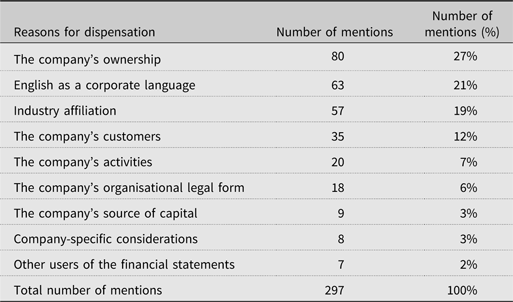

As is evident from Figure 2, the vast majority of the Kapital companies are organised as limited companies. Limited companies in Norway can be organised as either private limited companies, known as aksjeselskap, or public limited companies, known as allmennaksjeselskap. Combined, these two categories of limited companies make up 88% of the Kapital companies. Although private and public limited companies share many characteristics, an important distinction between the two is that public limited companies, unlike private limited companies, are listed on the Stock Exchange. Public limited companies are allowed to raise capital from the general public through the sales of shares, which means that these companies often have a large number of shareholders (Company Formation Norway 2019).Footnote 13

Figure 2. Organisational legal form of the Kapital companies (in percent).

Data material from Kapital (2016) shows that the majority of companies were founded in the years after 1970. In total, 81% of the companies listed in Kapital (2016) were established in the period between 1970 and 2016 (i.e. when the present study was conducted). However, several of the companies are significantly older, and therefore have a longstanding history in Norway. The oldest company in the Kapital ranking is Sparebank 1 SMN, which was founded in 1823. In total, 16 of the Kapital companies were founded in the period 1800–1900, representing just over 3% of the companies.

4.2 Financial statements and language choice

Among the 492 companies included in this study, a large portion (36%) of the Kapital companies produced their financial statements in Norwegian only. These companies can largely be divided into two main groups: (i) companies with a strong local attachment (e.g. Felleskjøpet, the association of Norwegian farmers), and (ii) holding companies with the only purpose of controlling the stocks of other firms. These two groups of companies typically communicate with a limited number of people and usually people with Norwegian language competence – hence, a Norwegian version of the accounts will in most cases be sufficient.

As Figure 3 shows, 41% of the companies presented their financial statements in parallel language versions in Norwegian and English. A small number of companies (3%) presented their financial statements in a third language, including Swedish, Danish, German or French. Two companies with headquarters located in Sweden presented their financial statements in Norwegian and Swedish. These numbers show that a large portion of the Kapital companies (i.e. almost 45%) produced their financial statements in multiple languages with at least one foreign language in addition to Norwegian.

Figure 3. Language of the Kapital companies’ financial statements (in percent).

However, this is not the case for the 19% of the Kapital companies that presented their financial statements in English only. These firms have been granted dispensation from the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes. The grounds on which the Directorate of Taxes has approved the companies’ application for dispensation will be discussed in the final part of the paper.

4.3 Dispensation from the language requirement of the Accounting Act

This section of the paper will focus on the explicit reasons given by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes in their dispensation permits to companies that have been relieved from the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act Article 3-4. The presentation will outline the following nine distinct reasons as they are defined in the dispensation permits:

the company’s ownership

English as a corporate language

industry affiliation

the company’s customers

the company’s activities

the company’s organisational legal form

the company’s source of capital

company-specific considerations

other users of the financial statements

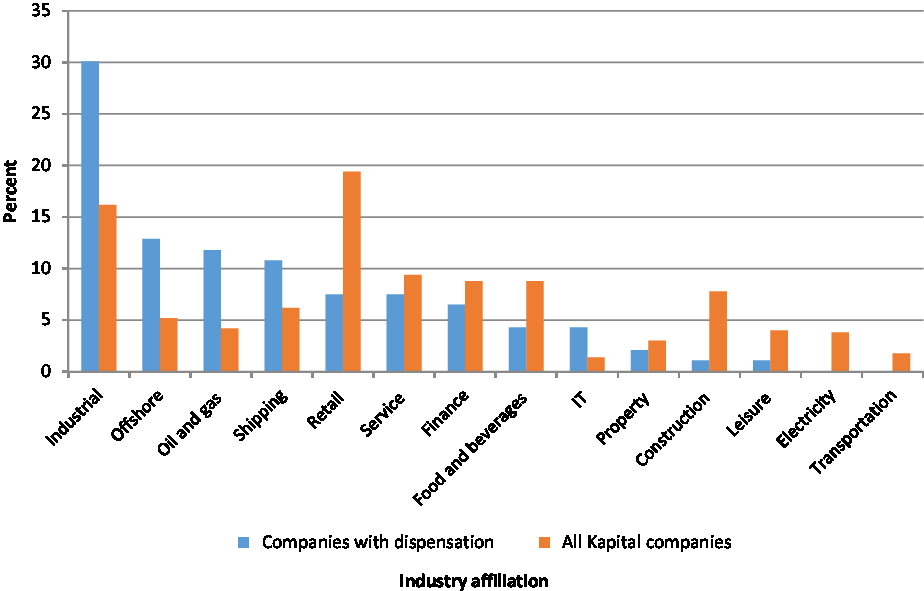

Table 2 summarises the frequency of each of the nine reasons stated by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes by total number of mentions and by percentage. The following presentation is structured according to how frequently these reasons are mentioned in the total number of dispensation permits.

Table 2. Reasons for dispensation from the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act Article 3-4 by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes.

4.3.1 The company’s ownership

The company’s ownership is the most frequently mentioned reason why companies have been granted dispensation from the language requirement of the Accounting Act. The Norwegian Directorate of Taxes explicitly mentions foreign ownership in a total of 80 dispensation permits. The Directorate of Taxes’ reference to the company’s ownership may be brief, as in the case of Seadrill AS, where they simply state that ‘The company has foreign owners’Footnote 14 or somewhat more elaborate, as in the case of Nexans Norway AS: ‘In this evaluation, the Directorate of Taxes has considered the company’s direct and indirect foreign owners, which involves a limited group of ownership interests’.Footnote 15

On the one hand, it is not surprising that foreign ownership and possible future owners are given importance in the Directorate of Taxes’ interpretation and application of the Accounting Act. Annual reports written entirely in Norwegian would not be accessible to investors without Norwegian language skills, and the use of English allows companies to communicate their financial information to a larger group of investors (see Jeanjean et al. Reference Jeanjean, Lesage and Stolowy2010). On the other hand, emphasis on the company’s ownership implies less consideration to other users of the annual reports, for example, the company’s employees or inhabitants in Norway. Translation of annual reports can therefore represent a disenfranchisement problem by excluding stakeholders with limited English skills (see Evans et al. Reference Evans, Baskerville and Nara2015:28).

4.3.2 English as a corporate language

Foreign ownership may require the use of English for internal reporting, also known as English as a corporate language (Lønsmann Reference Lønsmann2015). In their dispensation permits, the Directorate of Taxes refers to the companies’ use of English for internal communication purposes as a ‘corporate language’, ‘working language’ or ‘language of reporting’ in a total of 63 dispensations. For example, in the case of Scandza AS, the Directorate writes that ‘In this evaluation, the Directorate of Taxes has considered the company’s foreign owners and that English is commonly used for internal reporting and for other users [of the financial statements]’.Footnote 16

Language-sensitive research in international business offers insight into why companies choose to adopt English as a common corporate language. Piekkari et al. (Reference Welch and Welch2014) observe that a shared language can facilitate reporting within the organisation, and ensure that all employees get access to necessary documents, policies and procedures. A common corporate language can also improve informal communication and knowledge-sharing among employees in different geographical locations (Dhir & Gòkè-Pariolá Reference Dhir and Gòkè-Pariolá2002), and attract foreign professionals as new recruits (Piekkari & Tietze Reference Tietze, Stahl and Björkman2012). Another practical reason why companies in Norway choose to run their operations in English can be related to Norway’s EEA agreement and the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) issued by the IFRS Foundation (IFRS Foundation 2017). Although the dispensations covered in this study do not offer insight into the companies’ specific reasons for choosing English as a common corporate language, it is likely that the IFRS requirements could motivate companies to use English as the language of formal reporting, as noted by Piekkari et al. (Reference Welch and Welch2014) (see also Kettunen Reference Kettunen2017, for a discussion of language implications associated with IFRS).

4.3.3 Industry affiliation

The company’s industry affiliation is also frequently mentioned in the dispensation permits. The Directorate of Taxes states that global cooperation in the company’s industry has been taken into consideration in 57 of the dispensations. As in the case of Aker Solutions ASA, a provider of oil services for customers in the oil and gas industry worldwide (Aker Solutions 2018), the Directorate writes that ‘the company operates in an international industry where all key parties and business associates understand and communicate in English’.Footnote 17

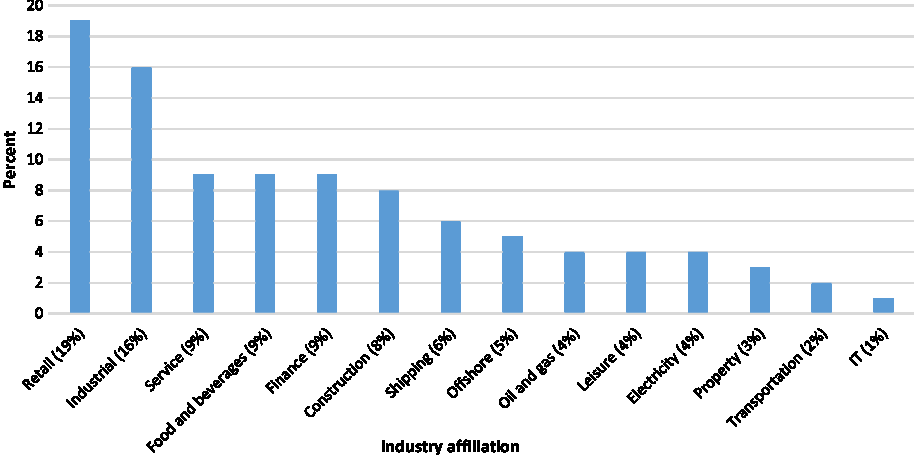

As mentioned in section 2.3, previous studies have found that industry affiliation provides important contextual information about language use (TNS Gallup 2015, 2016; see also Duchêne & Heller Reference Duchêne, Heller and Spolsky2012). Figure 4 below compares the percentage of dispensation permits according to industry sector with the industry affiliation of all Kapital companies, also in percent.

Figure 4. Comparison of industry affiliation of all Kapital companies and companies with dispensation permits (in percent).

As is evident from Figure 4, there are significant variations between industry sectors in terms of language choice. In particular, 30% of the dispensation permits were granted to companies in the industrial sector, which is an overrepresentation compared to the percentage of industrial companies among the Kapital companies (16%). Widespread use of English in industrial companies is in line with the findings from the Language Council of Norway and TNS Gallup’s survey (TNS Gallup 2016). The offshore sector also had a relatively high proportion of dispensation permits (13%), closely followed by oil and gas (12%) and shipping (11%). At the other end of the scale, there were no companies within electricity or transportation that had been granted dispensation by the Directorate of Taxes. And in property, construction and leisure the number of dispensation permits were limited to two or fewer companies.

4.3.4 The company’s customers

The company’s customers constitute another important target group for annual reports (see Gonzalez-Padron, Hult & Ferrell Reference Gonzalez-Padron, Hult, Ferrell and Malhotra2016). The company’s communication with customers is explicitly mentioned in 28 dispensation permits, while matters relating to the company’s operational activities are mentioned in 10 permits. In three of the permits these two conditions are mentioned in relation to each other, which means that the Directorate of Taxes explicitly refers to the company’s customers in a total of 35 dispensation permits. An example of how the Directorate has assessed this criterion can be found in the dispensation given to Nordic Semiconductor ASA, where the permit states that ‘the Directorate of Taxes has emphasised that nearly all of the company’s sales (over 99%) are from customers outside of Norway’ (English in the original).

The company’s customers are also mentioned in relation to other prevalent factors, as in the dispensation given to Akva Group ASA. Here, the Directorate of Taxes explicitly states that they have considered the fact that ‘the majority of shareholders are investors residing abroad, foreign nationals or companies, and that communication with the company’s primary customers and creditors primarily takes place in English’.Footnote 18 It is evident from these statements that international sales and customer contact outside of Norway are seen by the Directorate as legitimate reasons to opt out of the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act.

4.3.5 The company’s activities

Another reason for dispensation from the language requirement can be found in nature of the company’s activities. Aspects related to the company’s activities are mentioned in 20 of the dispensation permits. The Directorate of Taxes is somewhat vague in their formulation of this particular reason for dispensation, but treats it as a communication-related consideration based on the company’s international operations. For Philly Shipyard ASA, this is expressed in the following way: ‘The company builds ships in the United States. Their activities are therefore of strong international character and the working language is English’.Footnote 19 There are also examples in the dispensation permits where the Directorate simply states that the company’s business is international, as in the case of Norske Skog AS.

It is evident from the dispensations that the Directorate of Taxes pays special attention to the international nature of a company’s business activities, or the degree to which a company is involved in cross-border communication due to its business activities. However, evidence from previous empirical studies (see Sanden & Kankaanranta Reference Sanden and Kankaanranta2018) demonstrate that employees in internationally oriented companies frequently experience situations where they rely on their local language skills, even if their employer officially claim to use English as a common corporate language.

4.3.6 The company’s organisational legal form

The qualitative analysis of dispensation permits furthermore shows that the company’s organisational legal form is a factor that the Directorate of Taxes has included in their evaluations. As previously mentioned, companies that are listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange must obtain dispensation from the language requirement of the Securities Trading Act Article 5-13 in order to apply for dispensation from the language requirement of the Accounting Act Article 3-4. The Directorate of Taxes explicitly mentions dispensations from the Oslo Stock Exchange in 18 of the permits they have issued regarding the language requirement of the Accounting Act. This figure is lower than the total number of public limited companies that have been granted dispensation by the Directorate of Taxes, which indicates that the Directorate has taken the dispensation from the Stock Exchange into consideration without explicitly stating it in the permits. In cases where the Directorate of Taxes mentions the permit from the Stock Exchange in their assessment, it is usually very brief, as in the case of Marine Harvest ASA: ‘The company is listed on Oslo Børs and has permission to provide information in English’.Footnote 20

The Directorate of Taxes’ practice of giving emphasis to the company’s organisational legal form is only partially in line with the guidelines issued by the Directorate in 2012 (Skattedirektoratet 2012). In these guidelines, the Directorate states that ‘The organisational legal form of the company is not in itself a contributing factor’. It is therefore interesting to note that organisational legal form is mentioned explicitly in 18 dispensation permits, although it is never mentioned as the only reason for dispensation.

4.3.7 The company’s source of capital

As discussed above, the company’s ownership is brought up in a large number of the dispensation permits. But there are nine other examples showing that the company’s source of capital, which can be related to the financing structure of the company, and language and communication needs in relation to this structure also may constitute an important factor in the assessment conducted by the Directorate of Taxes. These cases demonstrate that the Directorate has considered the language needs arising from both intra-group relationships, i.e. where the company is financed solely based on its own equity and intra-group loans, and external circumstances, i.e. where there is a need for English language communication due to foreign bond holders. Idemitsu Petroleum Norge AS, which is wholly owned by the Japanese company Idemitsu Snorre Oil Development Co. Ltd., is an example of the first category, where the Directorate of Taxes states that: ‘The company is 100% financed by the parent company’.Footnote 21 Hurtigruten AS falls in the second category: ‘The group has a bond loan listed on a foreign stock exchange where they are obliged to present their financial statements in English’.Footnote 22

4.3.8 Company-specific considerations

In addition to the reasons discussed so far, there are a few dispensation permits where the Directorate of Taxes makes reference to company-specific considerations. Special circumstances or particular characteristics of the company are mentioned in a total of eight dispensation permits. These eight cases are somewhat different in nature. For example, in the dispensation given to Norsk Medisinaldepot AS, the Directorate states that it has ‘considered that the employees’ representatives on the board have agreed to prepare the annual accounts in English’.Footnote 23 In another case, in the assessment of Polarcus Norway AS, the Directorate states that they have ‘considered that the company does not have employees’.Footnote 24 Yet another type of company-specific considerations can be found in the case of Helly Hansen Group AS. This is a company that previously had been granted permission to opt out of the language requirement of the Accounting Act, but the company was required to reapply for permission due to changes in their organisational structure. In the new permit, the Directorate states that they ‘have emphasised that the company has previously been authorised to prepare their financial statements in English’.Footnote 25

4.3.9 Other users of the financial statements

The ninth and final category in this presentation involves other users of the financial statements, i.e. users of the financial statements that do not immediately fall into one of the previously mentioned categories. The Directorate of Taxes refers to ‘other users’ as an undefined category of stakeholders and their language proficiency in a total of seven cases. This is done by stating that there are no other groups (other than those already mentioned in the permit) that may require company-specific information in Norwegian, as in the case of DNO ASA. In this company’s permit, the Directorate writes that ‘The Norwegian annual accounts and reports are today therefore used only for submission to Regnskapsregisteret [the Register of Company Accounts]. There do not seem to be any key users of the accounts that may wish to have this in Norwegian’.Footnote 26

It is not clear from the dispensation permits how the Directorate of Taxes has assessed the language needs of ‘other users’ as these users have not been identified. It appears that administrative considerations have been given preference in the case of DNO ASA and the other six companies where lack of ‘other users’ are mentioned as a reason for dispensation.

5. Discussion

This study set out to examine the extent to which companies in Norway comply with the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act Article 3-4. The empirical results show that the majority of companies do comply with the requirement to produce financial statements and annual reports in Norwegian, but that a large percentage of companies (19%) have been granted dispensation to opt out of this requirement. The following discussion will focus on the companies that have received dispensation by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes, and discuss the Directorate’s interpretation and application of the language requirement of the Accounting Act, as well as the implications of this dispensation practice.

The qualitative analysis of the Directorate of Taxes’ dispensation permits indicates that elements of diglossia are present in Norwegian business. The many grounds on which the Directorate of Taxes has granted dispensation contribute to create an image of the Norwegian language as an insufficient language for business communication. In some cases this is true. When Norwegian companies are communicating with foreign owners, international clients, creditors or partners abroad, the choice not to use Norwegian appears to occur for two main reasons. Firstly, the decision to prepare the companies’ annual reports in English may be related to a limited or absent Norwegian language competence among key users, such as the company’s owners. In these situations, there is an uncontested need to produce financial information in English, and the preparation of an additional language version may constitute an extra administrative expense. In other situations, it is assumed that widespread use of English among those who read the financial statements renders a Norwegian language version unnecessary. This is an argument found in several dispensation permits presented in the findings section. There is an important difference between these two types of situations, as the perceived irrelevance of Norwegian is based on different considerations. In the first case, the use of English is due to lack of Norwegian language skills, whereas in the second case, it is due to good or adequate English language skills.

It follows from the observation above that the second category of situations contains more obvious elements of diglossia than the first category. If the use of Norwegian does not meet the company’s communicative needs, the choice of English can to a large extent be justified for instrumental reasons. In these cases, the choice not to use Norwegian comes as a result of an English language need, as the company is required to prepare its financial statements in English. In line with Jeanjean et al.’s (Reference Jeanjean, Lesage and Stolowy2010) argument mentioned earlier, companies use their annual reports to communicate with current and future investors, and the use of English makes it possible for companies to increase the base of potential investors. In the second category of situations, opting out of Norwegian is based on the assumption that the receivers of the company’s information are sufficiently proficient in English. This viewpoint will, according to Ferguson’s (Reference Ferguson1959) definition, coincide with the theory of diglossia, if it is seen as the primary reason for choosing English over Norwegian. In both these situations, the outcome is the same, but from a sociolinguistic point of view, the reasons behind the language choice are important factors when it comes to evaluating the status and position of the Norwegian language.

However, the findings of the study indicate variations between different industry sectors, which suggest that it may be too imprecise to refer to Norwegian business as a generic domain. In particular, the results indicate that the terms ‘domain’ and ‘domain loss’ are too wide to capture the differences between the various industry sectors. It is important to emphasise that the study has examined only a limited number of dispensation permits, but even though it is not possible to draw general conclusions based on this data material, the results may still shed light on some main tendencies between industry sectors. English language communication is unavoidable in sectors with a high degree of cross-border contact, but Norwegian is still the most commonly used language in industry sectors with strong local presence. For a number of such companies, the local connection is so deep-rooted that they do not find the need to produce financial statements in English at all. It would not be correct to describe Norwegian business as a ‘lost’ domain for the Norwegian language. To the extent that there is a loss of language, it appears to be bound to industry sectors rather than business overall, which in turn suggests that the term ‘domain loss’ should be replaced by ‘industry sector loss’.

One of the main reasons behind the language requirement of the Accounting Act is to ensure that important company information is made available in Norwegian to stakeholders in Norway. The findings presented in this study show that the Directorate of Taxes allows a large number of companies to opt out of this language requirement. The question remains, however, whether companies in Norway should be subjected to more extensive governmental regulation or if milder measures, such as language motivating campaigns, are enough.

On the one hand, Norwegian firms with aspirations to succeed outside of Scandinavia will in most cases have a legitimate need to use English and other foreign languages in their communication with international partners (see e.g. Piekkari et al. Reference Welch and Welch2014). For these companies, stricter language regulation in favour of Norwegian could represent an extra administrative burden. On the other hand, it is clear that companies in Norway have a responsibility when they communicate corporate information. Inhabitants in Norway have a legal right to access financial statements, and according to the Accounting Act, these statements should as a main rule be presented in Norwegian. This is a language requirement that creates a responsibility for companies to communicate in way that can be understood by the receivers of the information. But as suggested by Ferguson’s (Reference Ferguson1959) diglossia theory, companies in Norway also have a responsibility as senders of information. This responsibility involves using the Norwegian language to ensure that it continues to exist as a vibrant and expressive language that can be used for a variety of communicative purposes.

The use of parallel languages is often presented as the most promising strategy to combat diglossia and domain loss in Norway (Linn Reference Linn2010). Parallellingualism is given significant importance in the official language policy developed by The Norwegian Ministry of Culture and Church (Kultur- og kirkedepartementet 2008) and the Language Council of Norway (Språkrådet 2005; see also Språkrådet 2017), as well as the Nordic Council of Ministers (2006). However, the language policy documents barely address how the principle should be implemented in practice, and no recommendations are given to companies that wish to develop parallellingual strategies for communicating corporate information. In theory, parallellingualism can provide equality between the languages that co-exist in multilingual environments, but with no regulations, guidelines or incentives, companies in Norway may not consider parallellingualism a desirable option. As a result, English can be seen as an easy way around the Norwegian language requirement, as in the case of the Norwegian Accounting Act.

6. Conclusion

A company’s choice of language is an important strategic decision, especially for firms with international aspirations (Sanden Reference Sanden2016b). As discussed in this paper, current or potential foreign investors, the use of English as a corporate language, and international industry affiliations are some of the reasons why English can replace Norwegian as the language of financial reporting. These are all legitimate reasons for abandoning the use of Norwegian in annual reports according to Norwegian authorities, i.e. the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes. The official language policy of Norway suggests otherwise.

The language policy (Språkrådet 2005, Kultur- og kirkedepartementet 2008) suggests that companies should use Norwegian and English as parallel languages in order to cater to target groups with different language preferences. A large number of companies included in the present study publish their financial statements in English and/or another foreign language in addition to the Norwegian language version. This finding shows that parallellingualism can be used to reduce tendencies of diglossia and domain loss in Norway. However, the Directorate of Taxes current practice of granting full dispensation from the language requirement of the Norwegian Accounting Act challenges the principle of parallel language use in practice. A more nuanced dispensation policy that does not discard the use of Norwegian altogether would correspond better with the official language policy and the requirements of the legal framework as they exist today.

The present paper contributes to three streams of research that are concerned with the use of language in corporate contexts. Firstly, the paper contributes to the field of corporate law by examining the interpretation and application of the Norwegian Accounting Act by the Norwegian Directorate of Taxes. Methodologically, this study offers a legal perspective on the official language policy of Norway, and provides a novel analysis of corporate legislation as a form of language policy implementation. Secondly, this paper revisits and sheds new light on key concepts in sociolinguistic literature, namely the concepts of domain loss and diglossia. The findings reveal that there is evidence of diglossia in the dispensation permits issued by the Directorate of Taxes, but only in cases where the use of English cannot be justified by lack of Norwegian language skills among the readers of the financial information. Finally, by analysing language use in Norwegian companies, this paper contributes to language-sensitive research in international business. Unlike most of the existing research in this field, which tends to focus on the firm as the unit of analysis, the findings from the present study illustrate how national legislation can affect the use of language inside the firm. This observation demonstrates the importance of the national legislative context in the study of international business practices.

The findings of the study provide insights into how companies comply with a specific legal provision concerning language use, and the reasons why the authorities deviate from this language requirement by granting dispensation permits. As this is a study solely focusing on language policy and corporate law in Norway, future research could investigate the compliance or non-compliance with other legal provisions in other legal contexts. Future research could also examine the different perspectives involved in the regulation of language practices, for example, the perspective of an internationalising firm or the perspective of relevant stakeholders such as investors or employees.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions during the review process. This paper was written while the author was visiting Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University; the support of the Weatherhead Center, SCANCOR, and fellow SCANCORians is gratefully acknowledged. The author would also like to thank Rebecca Piekkari for valuable feedback on an earlier version of the paper, and Pierre-Antoine Tibéri for much appreciated assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Appendix. Overview of codes by company