Introduction

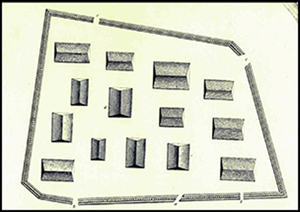

In 1804, Russian colonising forces, with the support of their Aleut subjects, fought a major battle against native Tlingit clans in what is now Sitka, Alaska (Figure 1). The story of the battle was recorded in Russian sources (e.g. Lisyansky Reference Lisyansky1814) and passed down in Tlingit oral history (e.g. Dauenhauer et al. Reference Dauenhauer, Dauenhauer and Black2008). Although accounts vary in some details and perspectives, a general description of the battle and associated fort emerged (Nordlander Reference Nordlander1998; Black Reference Black2004; Vinkovetsky Reference Vinkovetsky2011). The Tlingit defended Shís'gi Noow, or ‘the sapling fort’, on a peninsula at the mouth of the Kaasdaheen (now Indian River), which was sheltered from Russian naval artillery by wide tidelands. After an initial engagement that included a failed Russian/Aleut ground assault, Russian/Aleut forces retreated under cover of naval gunfire. The Tlingit victory was short-lived. With gunpowder running low, Tlingit elders decided to abandon the fort during an overnight tactical withdrawal. Russian/Aleut forces razed the abandoned structure, but not before recording a detailed map (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Location of Sitka National Historical Park (courtesy of the U.S. National Park Service, Sitka National Historical Park).

Figure 2. Top: historical drawing of the sapling fort (by Y. Lisyansky; courtesy of the U.S. National Park Service, Sitka National Historical Park); bottom: photograph of interpretive sign at fort clearing (courtesy of Sitka National Historical Park).

The battle, considered a pivotal moment in both Tlingit history and the history of Russian America, resulted in the establishment of a Russian colony on Baranov Island in 1804. This lasted until 1867, when the Russians sold their interests in Alaska to the USA (Nordlander Reference Nordlander1998; Black Reference Black2004; Vinkovetsky Reference Vinkovetsky2011).

In 1910, President William H. Taft established Sitka National Monument to commemorate the fort site and battlefield. The site was re-designated Sitka National Historical Park in 1972, expanding recognition to the period of Russian occupation, as well as the historical significance of the 1804 battle. Since the original National Monument designation, several archaeological investigations have been undertaken to determine the true location of the ‘sapling fort’. Results of these efforts have been either contested (e.g. Hadleigh-West Reference Hadleigh-West1958) or inconclusive (e.g. Hunt Reference Hunt2010a & Reference Huntb), leading some to speculate that the fort was in a different location (Thornton Reference Thornton1999).

While the U.S. National Park Service had designated a probable location for the fort at an open area on the forested peninsula known as the ‘fort clearing’, alternative locations were suggested and the question remained unanswered, with many believing the debate would never be resolved. Building on clues from previous investigations, a large-scale geophysical survey that included electromagnetic induction (EM) and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) was recently undertaken in an attempt to settle the question. The EM survey was the largest archaeological geophysical survey ever undertaken in Alaska, covering approximately 17ha.

Methods

EM equipment included a Profiler EMP-400 multi-frequency field system by Geophysical Survey Systems Inc., with Tripod Data System Recon-400 PDA. The instrument was operated in the horizontal co-planar configuration (vertical dipole moment) with in-line coil alignment, and carried at grade level (i.e. shin height), using the low-carry handle set-up. On site, instrument calibrations were conducted at an established base station. Three operating frequencies were sampled (1kHz, 5kHz, 15kHz), at a sample rate of 1Hz, with line-frequency filter set to 60Hz. Due to the forested nature of the site, a manual grid set-up on a large scale was deemed impractical. The data were therefore collected using internal Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) GPS. The GPS generally tracked at least seven satellites during data collection (with four required for validity). Processing included basic data editing and transformation of the coordinate system from decimal degrees (latitude/longitude) to Universal Traverse Mercator (UTM) using MagMap2000 software (Geometrics Inc.). The Kriging algorithm was used for gridding and data interpolation. Subsequent EM images were developed using Surfer 14 mapping software by Golden Software Inc., with the primary output being colour relief maps, with a combination of colour and texture indicating anomalous trends.

GPR Equipment included a Noggin series 250MHz unit by Sensors and Software Inc. deployed on a small sled. Set-up included an 80 nanosecond time-window, 8 stacks and 50mm trace interval (wheel-triggered). GPR transects were anti-parallel (FOR/REV) lines, with distances measured both manually by tapes (also used as collection guidelines) and logged with a calibrated odometer. Transects were collected in both the north–south and east–west directions, with each new pass spaced at 1.0m. GPR data-processing was done with EKKO_View and EKKO_mapper software (Sensors and Software Inc.) and included dewow, gain, background filter, migration and envelope. Velocity estimates (for conversion of two-way time to depth) were determined using the hyperbola fitting method. Profiles were organised into grids for time-depth slicing and 3D export. GPR images were produced with VOXLER 4 and Surfer 14 by Golden Software Inc.

Results

Both the GPR and the quadrature EM component (associated with electrical conductivity) revealed a pattern that matches historical descriptions of the fort, in terms of both shape and scale (Figure 3). The in-phase EM component (associated with magnetic susceptibility) revealed a number of metallic anomalies. Some of these were caused by more recent activity and debris noted during the survey, while others had no obvious explanation and are possibly related to the battle (Figure 4). We note, for example, that cannon balls had previously been found by Hunt (Reference Hunt2010a & Reference Huntb).

Figure 3. Electromagnetic induction (EM) quadrature result (showing the area south of the Indian River), indicating variations in electrical conductivity shown with associated ground-penetrating radar results. The two methods reveal a similar anomalous pattern at the same location, which bears striking resemblance to the historical drawing of the fort; figure by T. Urban).

Figure 4. Electromagnetic induction (EM) in phase result for the broader survey (areas south and north of the Indian River). The strong anomalies are caused by ferrous metals, some of which are related to more recent activities at the park, while others may be related to the battle. The ground-penetrating radar result has been overlaid in the appropriate location (figure by T. Urban).

Discussion

In recent years, geophysical methods have been gaining traction in Alaskan archaeology, yielding a range of new discoveries and insights spanning the full human history of the region (e.g. Urban et al. Reference Urban, Rasic, Alix, Anderson, Manning, Mason, Tremayne and Wolff2016, Reference Urban2019; Urban Reference Urban, Anderson and Anderson2019). These published surveys, however, are on a much smaller scale than the Sitka EM survey. The definitive physical location of the Tlingit sapling fort has eluded investigators for a century, and a large-scale survey was necessary to rule out alternative locations convincingly for this historically and culturally significant structure.

The GPR and EM surveys together provided consistent and complementary evidence supporting the probable location of the fort site. The anomalous trends detected by both geophysical methods revealed a pattern that closely matches the shape and dimensions described in historical documents and transmitted through oral accounts. In the broader EM survey, no other trends match the expected footprint of the fort. The method therefore offers no evidence to support the hypothesis of an alternative location for the fort, at least within the area covered by the survey. We therefore believe that the geophysical survey has yielded the only convincing, multi-method evidence to date for the location of the sapling fort—a significant cultural resource in New World colonial history, and an important cultural symbol of Tlingit resistance to colonisation.

Although there are no plans for additional work at the site, the new results must be considered in light of previous archaeological work, as our new findings lend additional context to these earlier investigations. In particular, the anomalous shape detected with the geophysical surveys appears to match the descriptions and plan drawings of Hadleigh-West (Reference Hadleigh-West1958), who claimed to have found remnants of the south and west walls of the fort. Further, some of the survey and excavation results of Hunt (Reference Hunt2010a & Reference Huntb) might be reconsidered, especially the location of cannon balls and shot found in the north-west corner of the proposed fort site (Figure 4).

Regarding Alaskan native communities, the location and protection of the fort site and broader battlefield has long been of significant interest to the Sheetka Kwaan Tlingit, especially those of the Kiks.adi Clan. Tribal members have maintained ongoing involvement and interest in archaeological work within the park, and representatives of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska have responded favourably to the new findings.

Funding statement

This work was supported primarily by a Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Units agreement between Cornell University and the Alaska Regional Office, Cultural Resources Division, and in part by funding from the Nation Center for Preservation Technology and Training.