Theories of deliberative democracy have directed scholars to pay attention to exposure to difference in political conversations. In most accounts, deliberation would seem to require at least inclusiveness, or even equality, in representation across the spectrum of relevant characteristics including race, gender, and partisanship (Dutwin Reference Dutwin2003; Fishkin Reference Fishkin1991; Schneiderhan and Khan Reference Schneiderhan and Khan2008). Moreover, the expression of, and exposure to, different viewpoints is a key component of political deliberation. When deliberation—or more generally, political conversations—include discussion about different values, opinions, experiences, and evidence, it is believed to produce valuable outcomes. These include, but are not limited to, increased understanding of the views of others, increased tolerance of differing viewpoints, a feeling of greater legitimacy of political outcomes, and possibly even better outcomes through altered perspectives (Mutz Reference Mutz2006).

Most of the scholarship on exposure to political difference (or “cross-cutting conversation”) has emphasized interaction between people who identify with different political parties or ideologies (e.g., Eveland and Hively Reference Eveland and Hively2009; Klofstad, Sokhey, and McClurg Reference Klofstad, Edward Sokhey and McClurg2013), who support different political candidates (e.g., Huckfeldt and Sprague Reference Huckfeldt and Sprague1995), or who more generally disagree about politics (e.g., Mutz Reference Mutz2006). Some studies tap a broader concept of “heterogeneity” that combines not only partisan or ideological difference, but also gender and racial difference among discussion partners (e.g., Hutchens et al. Reference Hutchens, Eveland, Morey and Sokhey2018; Scheufele et al. Reference Scheufele, Nisbet, Brossard and Nisbet2004). In these cases, racial difference is combined with many other factors to tap a more general concept. Most studies of exposure to difference consider only more general discussion of politics or election campaigns and eschew consideration of multiple distinct political topics (for a rare exception, see Cowan and Baldassarri Reference Cowan and Baldassarri2018). Despite these constraints, there remains considerable debate about exactly how much exposure there is to political difference (Eveland, Appiah, and Beck Reference Eveland, Appiah and Beck2018; Huckfeldt, Johnson, and Sprague Reference Huckfeldt, Johnson and Sprague2004; Klofstad et al. Reference Klofstad, Edward Sokhey and McClurg2013; Mutz Reference Mutz2006).

It is exceedingly rare in the literature on political discussion and political discussion networks to closely examine the extent and implications of interracial communication—in particular, talk between Blacks and Whites—about political issues that are explicitly tied to race (for exceptions, see Mendelberg and Oleske Reference Mendelberg and Oleske2000; Merelman, Streich, and Martin Reference Merelman, Streich and Martin1998; Walsh Reference Walsh2007). This may be in part due to methodological reasons—for instance, understanding the political networks of Blacks is difficult because of their low numbers in national sample surveys commonly used in this literature—but also because of the more generic emphasis on politics and partisanship in the political science literature. However, some consideration has been paid to the topic from a deliberative and philosophical standpoint, noting the potential value of alternative means of communication among racial minorities (Sanders Reference Sanders1997) or the value of opportunities for people with minority viewpoints to test and practice their talk within groups of similar others (Himmelroos, Rapeli, and Grönlund Reference Himmelroos, Rapeli and Grönlund2017).

This study answers four basic questions about interracial political discussion, where for both methodological and theoretical reasons, we limit interracial discussion to that occurring between Blacks and Whites: (1) How common is it to have interracial political conversation partners against a comparison baseline of having interparty political conversation partners? (2) What factors predict having interracial political discussion partners, and are these factors any different from those that predict interparty discussion? (3) What dyadic factors predict racial and partisan similarity in networks? Finally, (4) what dyadic factors predict political conversations about various political topics, including race-related topics such as police treatment of Blacks as well as topics not explicitly race-related such as health care and the 2016 presidential primary campaign?

IMPORTANCE OF POLITICAL CONVERSATIONS ABOUT AND ACROSS RACE

Recent events in the United States related to the treatment of Blacks by police have renewed longstanding calls for interracial dialogue (Excerpts From 1997). Given the political, racial, and cultural climate in the United States today (Abramowitz Reference Abramowitz2018), understanding interracial network composition and race-related topics of political conversation is especially important. Indeed, some political scientists have argued that U.S. politics is inherently structured by race and racial issues (Hutchings and Valentino Reference Hutchings and Valentino2004). Evidence suggests that Blacks and Whites tend to live—both geographically and metaphorically—in enclaves that contribute to making interracial interactions rare (Enos Reference Enos2017; Smith, McPherson, and Smith-Lovin Reference Smith, McPherson and Smith-Lovin2014). Any discussion of race—especially when it relates to how agents of government (i.e., the police) treat Blacks—embeds a political and often partisan component within more general interactions between Blacks and Whites. This is particularly salient given the correlation between race and partisanship in the United States that leads the vast majority of Blacks to identify with the Democratic party, widening the chasm if both race and partisanship independently serve as dimensions of political and topical avoidance. Moreover, a recent survey suggests race relations in the United States are at their lowest point in decades, and many Americans believe it will get worse (Thompson and Clement Reference Thompson and Clement2016). Both Democrats and Republicans agree that race relations are a national problem (Thompson and Clement Reference Thompson and Clement2016). Blacks and Whites hold remarkably divergent positions on important social, political, and racial matters (Pew Research Center 2016). For instance, 69% of Blacks believe that police unfairly target minorities, yet only 29% of Whites agree (Schneider Reference Schneider2015).

Perhaps the most promising first step in improving race relations is interracial contact. Intergroup contact theory (Allport Reference Allport1954; Pettigrew Reference Pettigrew1998) has shown that positive contact can reduce prejudice and improve interracial relations (Northcutt Bohmert and DeMaris Reference Northcutt Bohmert and DeMaris2015; Pettigrew and Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2008). In some cases, simple exposure to, or contact with, outgroups can significantly increase liking for those outgroup members (Harmon-Jones and Allen Reference Harmon-Jones and Allen2001). A meta-analysis revealed that interracial contact increases individuals' knowledge about and empathy for out-group members (Pettigrew and Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2008), which contributes to the reduction of prejudice and stereotyping (Galinsky and Ku Reference Galinsky and Ku2004) and improves interracial attitudes (Finlay and Stephan Reference Finlay and Stephan2000).

Interracial contact is important for positive race relations but contact alone is insufficient. The greatest benefits are likely to arise from or be enhanced through discussions after the contact has been established. Dialogue about race-based topics can be important to combat prejudice, foster mutual understanding, and nurture racial harmony (Sue et al. Reference Sue, Lin, Torino, Capodilupo and Rivera2009; Willow Reference Willow2008). Discussion of racial topics can lead to more than mere tolerance of other racial groups; it can produce understanding, acceptance, and even celebration of diverse groups. Research shows that intergroup dialogues can offer participants one of the first meaningful opportunities to explore sensitive racial issues (Zúñiga and Nagda Reference Zúñiga, Nagda, Schoem, Frankel, Zúñiga and Lewis1993), discuss differences, clarify misconceptions, and challenge stereotypes (Rojas et al. Reference Rojas, Shah, Cho, Schmierbach, Keum and Gil-De-Zuñiga2005; Zúñiga and Sevig Reference Zúñiga and Sevig1997). Understanding issues from the perspective of those who “speak on those issues with a voice carrying the authority of experience” (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999, p. 644) can offer a particularly compelling reason for interracial discussion of political—and race-related—topics.

Bracketing describes the unspoken process by which those engaged in dialogue set aside or “bracket” any portion of their self-identities perceived to hinder objectivity during group interactions (Tufford and Newman Reference Tufford and Newman2010). By bracketing, otherwise salient traits such as race, gender, or sexual orientation are kept contained to prevent the emergence of biases that would curtail a productive deliberation process (Rawls Reference Rawls1999). Some scholars argue against bracketing to facilitate constructive dialogue among interracial discussion partners (see Schneiderhan, Khan, and Elrick Reference Schneiderhan, Khan and Elrick2014; Trawalter and Richeson Reference Trawalter and Richeson2008). Bracketing can deny discussion participants' ethnic experiences, artificially create homogeneity, silence marginalized groups, and prevent the discussion of certain topics that embrace ethnically diverse experiences (Schneiderhan et al. Reference Schneiderhan, Khan and Elrick2014). Therefore, bracketing or avoiding topics about race during interracial conversations may be counterproductive. Some evidence suggests that racially heterogeneous groups that embrace rather than bracket their ethnic differences communicate more effectively (Page Reference Page2007; Schneiderhan et al. Reference Schneiderhan, Khan and Elrick2014). However, other studies identify challenges regarding the efficacy of cross-race talk about race (e.g., Mendelberg and Oleske Reference Mendelberg and Oleske2000; Merelman et al. Reference Merelman, Streich and Martin1998; Walsh Reference Walsh2007).

Expectations

Based on what we know about both interracial discussion and discussion among those with different political preferences, as well as what we know about the intersection of race, party, and political preferences, we have several expectations. First, we expect that Blacks will be more likely to have racial difference in their political discussion networks than Whites. This expectation is based largely on the opportunity structures in the larger environment, in which Blacks are a statistical minority embedded within a White majority. Thus, opportunities for Blacks to interact with Whites about any topic are more numerous than Whites' opportunities to interact with Blacks (Quillian and Campbell Reference Quillian and Campbell2003). Similarly, it is easier for Whites to construct completely homogeneous discussion networks—due to the greater availability of other Whites—than it is for Blacks who comprise a much smaller proportion of the larger population. Of course, factors such as segregation, as well as simple geographic variations in partisanship, can alter the overall population opportunity structures when considered at a smaller geographic level such as state or even neighborhood.

Second, we expect that Democrats will have more racially diverse political networks than Republicans. This expectation is because Democrats are more likely to talk to other Democrats, and Republicans are more likely to talk to other Republicans (Mutz Reference Mutz2006). There are few Black Republicans; 80% of Blacks identify with the Democratic party, whereas Whites are roughly split from 40% Democrat to 49% Republican (Pew Research Center 2015). Therefore, independent of any racial preference, White Democrats would have a greater chance of talking politics with Blacks because of shared political preferences. By the same token, White Republicans would be less likely to talk to Blacks if for no other reason than because of divergent political preferences of those (largely Democratic) Blacks.

Third, we would expect that Whites would have a greater likelihood of exposure to partisan difference. If we assume that there are relatively high levels of racial similarity in political discussion networks, that racial similarity would place a greater constraint on Blacks' exposure to political difference than to Whites. A Black person in an all or largely Black discussion network likely has little access to Republicans in that network since most Blacks are Democrats. On the other hand, a White person with an all or largely White discussion network would—all else equal—have roughly equal chances of having Democrats and Republicans in that network. Furthermore, in the United States, the characteristic of “White” is less diagnostic of partisanship than is “Black.” So, for those who would attempt to construct a partisan network, selecting on racial similarity would produce more political similarity for Blacks than Whites.

Finally, we would expect racial differences to influence the likelihood of discussion of some specific political topics. Topics that have a racial component (e.g., police treatment of Blacks and affirmative action) are likely to be discussed more by Blacks and in same-race Black dyads than by Whites and same-race White dyads because these issues more directly affect Blacks. A simple explanation of this is self-interest; people are more likely to talk about issues that are relevant to them or directly affect them and their loved ones than other issues.

Presuming a zero sum game with regards to topic selection—that emphasis on some topics is made at the cost of emphasis on other topics—we would expect that topics not explicitly or primarily about race, such as the 2016 presidential primary candidates and health care, would be more commonly discussed among same-race White than same-race Black dyads, once all else was held constant. Immigration—an issue largely unrelated to whether someone is White or Black, even though it has racial or ethnic components—would likely fall somewhere between.

Perhaps most interesting but least clear is what to expect regarding topic discussion among mixed-race dyads. Topics of conversation between two individuals are not uniquely in the complete control of either because, as Kellermann and Palomares (Reference Kellermann and Palomares2004, p. 308) note, “topics arise in talk nonrandomly, their occurrence is managed, and the management is consequential.” Two distinct literatures would lead to different predictions. On the one hand, regardless of individual interest in the topic, sensitive racial topics might be discussed the very least among mixed-race dyads because of the increased potential for anxiety, conflict, or hurt feelings. Studies of topic avoidance suggest one key reason for this avoidance is protection of the individual or the relationship (Palomares and Derman Reference Palomares and Derman2019). Blacks may be susceptible to racially insensitive remarks made by Whites during such discussions (Comas-Diáz and Jacobsen Reference Comas-Diáz and Jacobsen2001), but Whites might also eschew talking about race with Blacks to avoid even an inaccurate appearance of racism (Tatum and Sekaquaptewa Reference Tatum and Sekaquaptewa2009). More generally, there is an extensive literature on topic avoidance and suppressing verbal expressions of opinion in the presence of disagreement (e.g., Hayes Reference Hayes2007; Simons and Green Reference Simons and Green2018).

On the other hand, mixed-race dyads may provide the impetus for the introduction of race-related political topics among members of the White majority who otherwise might not find the topics sufficiently relevant for discussion. The driving force may come from either the Black or the White member of the dyad. Some Blacks may feel compelled to raise race-related issues or experiences with Whites—or even call out racism—when it becomes relevant during the discussion of other topics. They might also raise these topics with Whites in the hopes of recruiting them as allies on race-related issues. Some Whites might seek to take advantage of the opportunity to gain new insights and perspectives on race-related topics when talking with Blacks for self-expansion purposes (Dys-Steenbergen, Wright, and Aron Reference Dys-Steenbergen, Wright and Aron2016) —something they might not bother to do when talking to other Whites under the assumption that other Whites would lack pertinent experience or perspectives.

Finally, Whites may raise political topics with Blacks that Blacks would otherwise not discuss in same-race dyads. That is, Blacks in mixed-race dyads may feel compelled to talk about non-race-related political topics more often than Blacks in same-race dyads because their White discussion partners raise those issues, and it is impolite to refuse to discuss them when raised. Blacks might even raise those issues in their discussions with Whites because they (like Whites) make assumptions about what their opposite-race discussion partners may be most interested in discussing. Conversational topics are often selected for strategic purposes and sometimes those purposes are related to building or maintaining relationships. This means that negotiating topics of conversation may mean that dyads meet (roughly) in the middle of their individual interests in topics.

In short, topic selection during the political discussion is likely to be the product of a complex push–pull process both within individuals and within dyads. There are reasons that draw individuals to topics (e.g., interest, salience), and there are reasons to avoid them (e.g., disagreement, sensitivity). These factors exist in both members of the dyad, and could often differ across those individuals. Therefore, the impact of avoidance and bracketing—leading to less discussion of race-related topics in cross-race dyads—may cancel out the impact of selective focus on racial topics for the purposes of enlightenment, persuasion, or following conversational norms of pliability to one's discussant's preferences. Or, one or the other of these forces may dominate. So, we simply ask the research question: on which if any issues will Blacks and Whites in opposite-race dyads differ in the discussion of different topics compared to same-race Black and White dyads?

METHOD

Sample

Data were gathered from a nationally representative sample of the United States by YouGov between April 29 and May 7, 2015. The survey was conceived during a time in which there was substantial news coverage of police treatment of Blacks and the Black Lives Matter movement, perhaps sparked by the summer 2014 police killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, MO and Eric Garner in New York City, and the fall 2014 killing of Tamir Rice in Cleveland, OH. News of those cases led to widely covered protests after the events and following December 2014 decisions not to charge the officers involved in the Brown and Garner cases. Our survey was designed in the context of these events, and then fielded immediately following another similar case: protests and rioting in Baltimore, MD during late April which followed the April 19, 2015 death of Freddie Gray—another Black man—from injuries obtained while in police custody on April 12, 2015. Protests and rioting took place in Baltimore from roughly April 18 to 28, 2015; our survey began the following day. Gray's death was ruled a homicide on May 1, 2015.

In addition to 800 respondents (574 White, 81 Black, 68 Latinx, and 77 multi-racial or multi-ethnic; 46.3% Democrat or leaning, 32.0% Republican or leaning, 21.8% Independent, other, or not sure) in our general population survey, we also gathered data on Black oversample of 198 additional non-multi-racial Black respondents (83.3% Democrat or leaning, 3.0% Republican or leaning, 13.6% Independent/other/not sure). This was designed to give us sufficient statistical power to describe Black political discussion networks in a way that is not normally possible in representative surveys. Our data do not permit us the ability to reasonably describe multi-racial or multi-ethnic respondent networks, nor the networks of Latinx. Therefore, all descriptive statistics below are based on a subset (N = 695) of the sample that excludes: (a) anyone reporting themselves as multiracial or a race other than Black or White because of small sample sizes in the other categories, the ambiguity of exposure to difference for multiracial individuals, and the different racial dynamics outside of the Black–White dichotomy; and (b) anyone reporting identifying as other than a Democrat or Republican (or leaner), because exposure to political difference with or by non-partisans is ambiguous (see Hutchens et al. Reference Hutchens, Eveland, Morey and Sokhey2018). Due to these significant exclusions from the sample, and the addition of the Black oversample, we have not applied sample weights in the analyses that follow.

Measures

Basic demographic and political variables

Gender was tapped with a single-item self-report, with female (53.4%) coded as the high value. Age (M = 49.69, SD = 16.86) was measured by asking respondents the year in which they were born, then subtracting that from 2015 (the year of the survey). Education was measured as a six-point ordinal variable from less than a high school degree through postgraduate degree; the modal response was 2 (high school graduate) and the median response was 3 (some college). Family income was measured as a 16-point ordinal variable from “less than $10,000” to “$500,000 or more” with a modal response of 3 ($20,000–$29,999) and a median of 5 ($40,000–$49,999).

Race was measured by asking respondents “What racial or ethnic group best describes you?” and allowing them to check all that apply from a list including White, Black, Latino/a, and other. As already noted, for the present analysis, we excluded all respondents who chose option(s) other than White (65.3%) and Black (34.7%).

Geography of residence and region was included as controls because of political (Tam Cho, Gimpel, and Hui Reference Tam Cho, Gimpel and Hui2013) and racial (Charles Reference Charles2003; Enos Reference Enos2017) segregation in the United States based on geography, and thus the role of geography as part of the opportunity structure for interaction and network tie formation (Wimmer and Lewis Reference Wimmer and Lewis2010). Geography of residence was measured by asking “How would you describe the place where you currently live?” with five possible response options: rural area/farm, small town, suburb, small city, and large city. For the analyses here, this variable was recoded into dummy variables: (a) rural, including the small town option (27.2%); and (b) “suburban” (36.4%), with the excluded category being respondents who chose urban, including small and large cities (36.4%). Region was a four-category variable constructed based on the state of residence to match the following regions as defined by the U.S. Census: West (22.4%), Midwest (22.0%), South (41.7%), and Northeast (13.8%). Note that by this definition, the category “South” includes DE, MD, and Washington, D.C.

Party identification was measured by first asking respondents “Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as a…” with options of Democrat, Republican, Independent, other, and not sure, followed by questions regarding strength of identification (for those who identified with one of the two major parties) and “leaning” among those who did not. As noted above, individuals who did not indicate identification with or learning toward either party were excluded, leaving 32.4% Republicans and 67.6% Democrats. (Note that the preponderance of Democrats is largely a function of our Black oversample.)

Name generator derived measures

In order to tap political discussion networks, we first helped respondents by giving them some context for the types of discussions we were interested in, since research has shown considerable variability in how respondents interpret questions about the political discussion (Morey and Eveland Reference Morey and Eveland2016). We began, “Next, we'd like to ask you a series of questions about your political conversations. When we say political conversations, we mean talk online (email, discussion forums, social media), via phone, or face-to-face about elections, politicians and candidates, and the performance of local, state, and national government.” This provided a broad and inclusive definition of politics—and the contexts in which conversations about it take place—for respondents before they were asked to report on this behavior. However, like most political discussion name generators, it did not specifically reference any political issues—in particular, issues related to race—and this could have implications for the answers to subsequent questions if respondents did not consider this or other topics within the bounds of the question. On the other hand, the timing of our survey during a period of high racial tension may have offset this limitation.

Next, we asked respondents to report, in general, the number of different people they talked politics with and the rough mix of partisan affiliations in their network. After this attempt to get them to think broadly about their political discussion networks, we employed a political network name generator to gather detailed information about a small subset of network alters. We began, “Next we would like you to think about the three people with whom you have most frequently talked about politics since the start of 2015. Please do not include your spouse or romantic partner.” We excluded spouses and romantic partners because (a) not all respondents will have this close network alter, making comparisons across respondents who do and do not more difficult; and (b) spouses and romantic partners tend to be very similar politically (Stoker and Jennings Reference Stoker, Jennings and Zuckerman2005) as well as racially.

We then asked respondents to name or otherwise describe up to three discussion partners. The number of network alters was constrained by the previous summary network size measure; respondents who reported zero political discussion partners were not asked the name generator items. Respondents who reported one or two discussants were only solicited for one or two alters based on the name generator. (This was an unintended constraint on the questionnaire implemented by the survey provider, unbeknownst to the researchers at the time. However, since summary measures tend to produce larger estimates of network size than name generators [Eveland, Hutchens, and Morey Reference Eveland, Hutchens and Morey2013], this should not meaningfully affect the results.)

Responses were used to ask a series of follow-up questions about these individuals and their political discussions. Among other questions, we asked respondents to report the race of each named alter (using a measure similar to that used to report their own race), the respondent's perception of the political party supported by the alter (retaining only those that perceived the alter as a Democrat or Republican), the days per week on average they talked to that person about politics since the start of 2015, and whether or not during that time period they had discussed each of five political topics with each alter: (a) 2016 presidential primary candidates or the 2016 presidential election; (b) immigration; (c) health care; (d) affirmative action; and (e) treatment of Blacks by the police.

Plan for Analysis

We analyze our data in two stages. First, we focus on understanding the factors that predict the presence of racial difference within political discussion networks. For these analyses, we employ binary logistic regression. We conduct the analyses for all respondents and then only for the subset of respondents who have at least one political discussant in their network. The latter helps distinguish not talking about politics at all with not talking with anyone who is different among those who do talk politics.

Next we consider, once at least one alter is present in the network, how individual (respondent demographics and political preferences) and dyadic (e.g., racial and political similarity in the dyad) factors influence the likelihood that the dyad is racially or politically similar. We also identify the factors predicting the discussion of specific political issues—some race-related, some not—being part of the political conversations in the dyad. These analyses of dyadic variables (racial similarity, partisan similarity, and topic-specific discussion) employ generalized estimating equations. We estimate each model once with, and once without interaction terms that allow similarity effects to vary by race.

RESULTS

We begin by considering the raw racial and partisan differences in exposure to racial and partisan difference. Within the general population sample only, 24.5% of respondents were exposed to partisan difference and 12.4% of respondents were exposed to racial difference in their political discussion networks. Sticking with the general population sample only, 8.5% of Democrats and 7.3% of Republicans have someone of the opposite race in their network. In terms of exposure to partisan difference, in the full sample (including the Black oversample to improve the precision of the estimate for Blacks), 14.9% of Blacks and 29.5% of Whites have at least one person from the opposite political party in their political discussion network.

Moving to our multivariate analyses and using the full sample including the Black oversample, Table 1 shows relatively weak and inconsistent effects of most demographic and political variables on exposure to racial or partisan difference. The two key variables that predict exposure to difference are political network size and respondent race. Those who talk to more people about politics—whether or not we exclude respondents who talk to no one—are more likely to name a discussant who is different racially and politically. As we expected, Whites are less likely to have someone racially different in their network than Blacks, but Blacks are less likely to have someone politically different in their networks than Whites. Holding other variables in the model constant, Blacks are 22 points higher in their likelihood of exposure to racial difference and 8 points lower in their likelihood of exposure to the partisan difference than are Whites.

Table 1. Logistic Regression Predicting the Presence of Any Racial and Partisan Difference in Networks

Coefficients are B values, with standard errors in parentheses.

Urban is excluded category for Place of Residence; South is excluded category for Region of Country.

*p < .05, two-tailed.

Next, we move to consider what individual- and dyadic-level factors predict racial and political similarity in a given dyad. We begin by considering analyses without interaction tests (both Model 1s in Table 2), and ultimately turn to the interaction tests (both Model 2s in Table 2). Once again, few political or demographic factors are significant predictors of racial or partisan similarity. On the other hand, Whites and those who are talking to co-partisans are likely to be of the same race as their political discussant. This co-partisan effect is only apparent among Blacks, however, who dramatically decrease the likelihood of sharing the race of a discussant when that discussant is from the opposite party. Whites are likely to share the race of their discussants regardless of the discussant's partisanship. In more explicit terms, regardless of whether they are talking to co-partisans or not, Whites talk politics with other Whites. Blacks, on the other hand, are much more likely to talk to Whites than Blacks when they are talking to out-partisans (see Figure 1, top panel).

Figure 1. Probability of a homophilous dyad by party/race similarity and respondent race

Note: Values are estimated marginal means from models in Table 2.

Table 2. Generalized Estimating Equations Predicting Dyadic Similarity (Racial and Partisan)

N = 428 respondents, 901 dyads. Coefficients are B values, with standard errors in parentheses.

Urban is excluded category for Place of Residence; South is excluded category for Region of Country. Note: *p < .05, two-tailed.

Race also is a significant predictor of exposure to partisan similarity, with Blacks more likely to do so than Whites. Racial similarity is associated with partisan similarity. But again, this relationship is moderated by race such that racial similarity in a dyad is a more powerful predictor of partisan similarity in the dyad among Blacks than among Whites (see Figure 1, bottom panel). That is, Blacks interacting with someone who shares their race are almost certainly talking to a co-partisan. This is also true, but less so, among Whites. Black and Whites interacting with someone from the opposite race, however, are roughly equally likely to share that person's partisanship. These findings have important implications as we discuss in detail later, but they largely simply highlight that since so few Blacks are Republicans, when a Black person is talking to a Republican, s/he is almost certainly talking to a White person and thus experiencing two types of difference simultaneously. Exposure to difference in race and partisanship is more closely aligned among Blacks than among Whites.

The characteristics of people involved in a political discussion network are one matter; what political topics are discussed within a given dyad in that network is another. To begin, Figure 2 reveals basic descriptive findings for the mean probability of having discussed a topic across all dyads, by race of the respondent. Not only is there considerable variability in the extent to which issues are discussed (e.g., regardless of respondent race, affirmative action is the least discussed topic), but there are some clear racial differences in discussion across topics.

Figure 2. Probability of dyadic topic discussion by race, including 95% confidence intervals

Note: Basic descriptive findings absent any controls.

Dyadic analysis (Table 3) prior to consideration of interaction terms suggests no consistent impact of most individual-level demographic variables on topic discussion. If anything, the intermittent significant findings suggest that perhaps for some topics, some particularly relevant characteristics might increase or decrease discussion. More consistently, those with high levels of political interest were more likely to discuss four of the five topics than those low in interest, and in dyads that talked politics frequently, all five issues were more likely to be covered than in those dyads that talked politics infrequently.

Table 3. Generalized Estimating Equations Predicting Dyadic Discussion Regarding Specific Political Topics within Political Discussion Networks

N = 428 respondents, 901 dyads. Coefficients are B values, with standard errors in parentheses.

Urban is excluded category for Place of Residence; South is excluded category for Region of Country. See Appendix Table for test of race by racial similarity interaction.

*p < .05, two-tailed.

The most theoretically interesting variables, however, were individual-level race and partisanship and dyadic-level racial and partisan similarity. As expected, Black respondents were more likely to talk about police brutality, but White respondents were more likely to talk about immigration, health care, and the presidential candidates. Democrats were less likely than Republicans to talk about immigration, but no other issue was distinguished by partisanship. Dyads that were similar with regards to partisanship were more likely to talk about police brutality, and racially similar dyads were less likely to talk about immigration, health care, and the candidates.

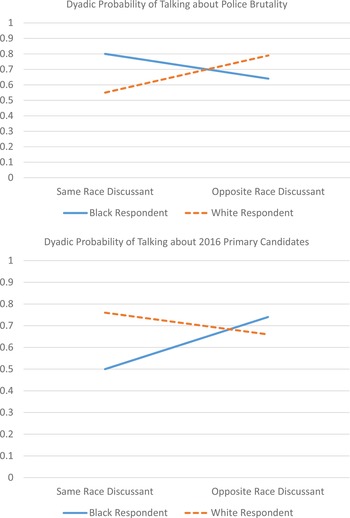

However, two of these relationships—police brutality (Wald χ2 = 5.145, df = 1, p = .023) and the 2016 primary candidates (Wald χ2 = 5.636, df = 1, p = .018)—were qualified by interactions between respondent race and racial similarity in the dyad (not shown in tables). Regarding the police brutality issue, White–White dyads talked about this issue least (55%) and Black–Black dyads talked about it the most (80%). But, when White respondents reported on opposite-race political discussants, they reported rates of discussing police brutality at roughly the same levels as Black–Black dyads (79%). Blacks reporting on opposite-race discussants reported a reduction in the discussion of police brutality (64%), but not as low as White–White dyads (Figure 3, top panel).

Figure 3. Probability of topic discussion by ego race and dyadic racial similarity

Note: Values are estimated marginal means from models in Table 3 but with interaction terms.

In almost mirror fashion, although White–White dyads discussed the 2016 primary candidates most often (76%) and Black–Black dyads least often (50%), when Black respondents reported on an opposite-race discussant, their likelihood of discussing the candidates increased to nearly the level of White–White dyads (74%). When White respondents reported talking with opposite-race discussants, their likelihood of talking about the candidates dropped (66%), but not as low as the level of Black–Black dyads (Figure 3, bottom panel).

As we have already noted, for health care and immigration, the probability of the topic being discussed was uniformly (i.e., regardless of ego race) greater in mixed than same-race dyads, and lower among Blacks than Whites. Indeed, only the affirmative action issue was unaffected by any combination of ego or dyadic race variables (see Appendix Figure).

DISCUSSION

Our study of cross-race discussion of politics, and in particular political topics related to race relations, is rare compared to studies considering more general exposure to the difference in terms of candidate or partisan preference. Our findings suggest interesting patterns relating to race and political and racial similarity in political discussion, both in general and regarding topics with and without explicit racial overtones. Although not a theoretical focus, it is important to note that our individual-level analyses make clear that racial difference in political discussion networks is driven largely by the size of those networks. The more people a person talks to, the more likely that person will have racial difference in his/her network; the same is true for partisan difference. This builds on arguments for placing a high value on network size as an important factor in future research on exposure to difference (Eveland et al. Reference Eveland, Hutchens and Morey2013), and also suggests that racial and political difference may be found the deeper we peer into political networks beyond the “core” networks typically studied in this literature (Eveland et al. Reference Eveland, Appiah and Beck2018).

A second key finding was that although Whites tend to have less racial difference in their political discussion networks, Blacks have less partisan difference in their networks. Both of these are likely, at least in part, to be a product of base rates of available discussion partners. There are fewer Blacks for Whites to talk to, and fewer Black Republicans for Black Democrats to talk to. Thus, low levels of exposure to difference may be mitigated at least partially through simple physical access to people whose characteristics are less prominent in a given population, a matter we will revisit in more detail shortly.

Moving on to the findings of our dyadic analyses, we were able to more clearly expound upon how matters of race, partisanship, and similarity interact with one another. For Blacks, race and party similarity are confounded. Blacks in same-race dyads are almost always experiencing political similarity as well. In order to experience partisan difference, they must simultaneously contend with racial difference, which may be particularly challenging. The same is not true for Whites, who can maintain same-race interactions while varying whether or not their discussion partner shares their partisanship. By the same token, White Democrats can maintain partisan similarity while experiencing difference on the criterion of race. This allows them to sustain some level of similarity while experiencing difference at the same time. White Republicans, on the other hand, have a harder time doing so, making exposure to racial difference for them even harder. In some sense, White Republicans' difficultly in encountering racial difference is very similar to Blacks (most of whom are Democrats) encountering political difference. White Democrats are in the “safest” position to experience both partisan and racial difference, by experiencing them one at a time rather than simultaneously. They are able to maintain one dimension of similarity while at the same time encountering one dimension of difference.

Finally, we also found that, unsurprisingly, Blacks are more likely to talk about topics that relate explicitly to race (police brutality, although not affirmative action), and, probably through a zero sum game logic, less often about topics such as presidential primaries and health care. Another way to view this is that Whites avoid talking about explicitly racial matters in favor of other political topics. But, there was promising evidence that cross-race talk could encourage Whites to engage on race-related topics. Rather than being less likely to talk about police treatment of Blacks with Blacks, if anything Whites were more likely to engage with this topic when talking to Blacks than other Whites. Blacks engaged more with the primary election candidates when talking with Whites. This finding demonstrates the value of exposure to racial difference in expanding the topics—and presumably, the information and insights—to which one is exposed.

Although this study offers some new insights into not only political discussion more generally but also where cross-racial conversations stand in the present political climate, there are some limitations that must be acknowledged. First, we have only examined cross-race talk within the “core” network of discussants, which likely hides the presence of political and racial difference deeper down in the network, among weaker ties (see Eveland et al. Reference Eveland, Appiah and Beck2018). Since we relied on respondent perceptions of partisanship, it may be that exposure to that difference is actually more prevalent than we found due to respondent errors in perception (see Eveland, Song, Hutchens, and Levitan in press). Moreover, we did not measure the extent to which there was disagreement expressed in the various topics of conversation—only that the topic was addressed. If the only topics that are discussed are those on which discussants share viewpoints, those conversations are potentially less valuable from a deliberative perspective, and they are less likely to increase interracial understanding. That said, if disagreement in the discussion is accompanied by emotional conflict and ill will, this too would be unlikely to improve race relations. Future research should work to more fully elaborate on the nature, rather than the simple presence, of conversations, especially in the domain of race (e.g., Tatum and Sekaquaptewa Reference Tatum and Sekaquaptewa2009). Finally, we hope that future research will evaluate the impact of such conversations, which we are unable to do with the data available at hand.

That said, the current racial climate and scholarly literature demonstrate there is a need for greater interpersonal contact across racially and politically diverse groups to increase mutual understanding, tolerance, and respect, especially in the wake of racial and political violence and acrimony following the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Meaningful intergroup conversations provide an opportunity for people to discuss sensitive and often taboo topics (Zúñiga and Nagda Reference Zúñiga, Nagda, Schoem, Frankel, Zúñiga and Lewis1993), which can address differences and challenge misconceptions and stereotypes (Zúñiga and Sevig Reference Zúñiga and Sevig1997). Substantive conversations, especially about politics and race, can foster greater intergroup awareness and lead participants to appreciate and value the perspectives and experiences of others. Ignoring issues of race is unproductive and harmful for interracial relations, leading many to call for a national dialogue on race to facilitate racial harmony and reconciliation (Sue Reference Sue2015).

Findings from this study show that although a public and national conversation on race may still be absent, interpersonal conversations about racial issues do exist within political discussion networks. Some racial issues (e.g., police brutality) are relatively prominent topics of conversation, although more so among Black dyads than White dyads. Additionally, Whites discuss at least some racial issues more often when in mixed than same-race dyads. This level of discussion of racial topics in our study is likely to have been driven at least in part by media coverage (King, Schneer, and White Reference King, Schneer and White2017). Future research should examine the role of news coverage in prompting conversations, particularly interracial conversations, about race.

This study points out that political conversations between Whites and Blacks are still relatively rare, which makes it important to discover other ways positive race relations can develop through cross-group contact. Extended intergroup contact theory maintains that knowing an ingroup member has a close friendship with an outgroup member also can lead to positive outgroup attitudes (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Aron, McLaughlin-Volpe and Ropp1997). This evidence is consistent with experimental research on “contagion” in political influence, where some stimulus, such as a message encouraging voting turnout delivered interpersonally, can ultimately influence others close to the person directly contacted (Nickerson Reference Nickerson2008). Extended or indirect cross-race friendships are less threatening, provide normative positive outgroup information (Hodson, Harry, and Mitchell Reference Hodson, Harry and Mitchell2009), and often lead to positive attitudes toward the outgroup (Park Reference Park2012). Future research should consider whether indirect contact with outgroup members could have a trickle down conversation effect such that talk about race between mixed-race dyads may ultimately result in increased conversations about race among same-race dyads with indirect interracial contact. Although it is important to have cross-racial discourse on matters of race, it is just as important to have intragroup discussions about race, especially among White–White dyads.

The role of race—as a topic of conversation, and as a dimension of difference—has been woefully understudied in the larger literature on exposure to the difference in political conversations. We view the efforts reported here as a modest first step, and hope for more steps from a wide range of perspectives to follow.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2019.36.