From 1986 to its 2009 collapse, the Stanford Financial Group reaped billions of dollars selling bogus certificates of deposit (or CDs) to thousands of mostly middle-class investors across the Americas. During that run, Venezuela was among Stanford’s first and most economically vital markets. The fraud is notable not just for its longevity and the scale of its harm—Stanford’s Ponzi Scheme left as many as nine thousand Venezuelan investors $2 billion poorer (CoVISAL 2012; Hernández Behrens Reference Hernández Behrens2009)—but for spanning a stretch of Venezuelan history marked by successive crises.Footnote 1 This includes a 1980s economic downturn that dashed Venezuelans’ dreams of sustained wealth and institutional modernity. It continued through 1989’s Caracazo, an urban conflagration in which the military gunned down hundreds of civilians protesting neoliberal austerity measures, and which cast a pall on Venezuela’s then 30-year stretch of two-party Puntofijo democracy. Stanford endured through the chaotic 1990s, a term marked by coup attempts, massive financial sector frauds, and growing social antagonisms. And it thrived through the heady and conflictual first decade of Chavismo. Through it all, the firm persisted and seemingly prospered. Stanford’s enduring appeal to Venezuelan investors, amid those historical zigs and zags, serves as my point of departure for exploring the ties between, on one side, what scholars have recently termed “imagined futures” (Beckert Reference Beckert2016) and “projectivity” (Mische Reference Mische2009, Reference Mische2014) and, on the other, illegality.

Existing treatments of futurity have focused chiefly on licit economies. Extant scholarship also takes for granted the importance of “legitimate” state institutions for such licit, future-oriented activity. In privileging lawful economies buttressed by upright institutions, futurity research rests on deeper assumptions about certainty. This is true in two respects. First, such works hold that the relative certainty furnished by capitalist “rule of law” institutional orders permits social actors to imagine and work toward projected future states. Thus, property law, contracts, courts, and the like provide state-backed assurances favorable to future-thinking. Second, futurity research assumes, too, that the lines between licit and illicit dealings, and between honest and corrupt institutions, are themselves largely clear to the actors involved. But what happens to those actors, and their grip on the future, when such lines blur?

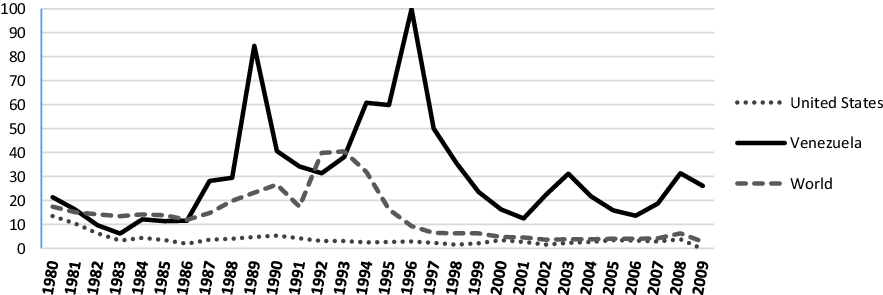

Drawing on 54 in-depth interviews with defrauded Stanford investors, firm employees, and others linked to the case, this article takes up this question through an analysis of certainty’s other: ambiguity. Stanford’s rise and fall transpired within a longer arc of Venezuelan economic and institutional crises. From the late 1970s through the early 2000s, vast swaths of Venezuelan life were slowly degraded. Middle-class Venezuelans saw their once-potent purchasing power eroded by inflation and currency devaluations (figures 1 and 2). Additionally, they came to regard the state—its clientelist two-party system, its judiciary, its graft-prone monetary policies—as sometimes faintly, sometimes flagrantly, criminal. At the same time, crucial questions for middle-class economic life—the solvency of domestic financial institutions, the legal repercussions of banking abroad or exchanging bolívares for dollars—were shrouded in doubt. Furthermore, middle-classness itself, a category increasingly tarred with amoral materialism, fell into discredit in this period, reaching its nadir under Chavismo, leaving middle-class Venezuelans unsure of their civil and legal standing.

Figure 1. Comparison of Inflation Rates, 1980–2009 (annual percent change)

Data Source: International Monetary Fund (2019).

Figure 2. The Ravages of Venezuelan Inflation, 1980–2009

This figure illustrates how US$1 million worth of bolívares would have fared if left idle in a Venezuelan savings account from early 1980 until 2009. Data Source: International Monetary Fund (2019).

As crisis became routinized, the data show, middle-class Venezuelans found themselves beset by “normative ambiguity,” my term to denote the progressive loss of legal and moral certainties they previously enjoyed. Such ambiguity, I demonstrate, drove a wedge between the state and the future-aimed temporality of middle-class Venezuelans. As their material prospects dimmed amid successive governments’ dysfunction, Venezuelans learned to see the state not as an institutional scaffold on which to drape their plans but as a set of hazards to mitigate and evade so that their own projects might come to fruition. It was in this mire—dubious of key institutions and unsure of their own status—that middle-class Venezuelans saw in Stanford and its high-yield CDs a path toward desired futures. In striving to reach their goals, in a setting where core features of political-economic life were neither clearly licit nor illicit, Stanford investors unwittingly walked into a criminal firm’s snare.

This article makes four contributions to research on futurity and to critical social studies of illegality. First, it brings those concerns into dialogue by stirring settled assumptions about how futurity and legality relate. Where extant scholarship highlights the power of state capitalism to foster future-thinking, this study shows what perils lie in wait for the future-oriented when state-backed legal and moral certainties buckle. Second, this research heeds Brooke Harrington’s recent call to point up the continuity between the “confidence” that sustains imagined futures and the “confidence” that fraudsters exploit (Reference Harrington2017). Futurity and fraud, she suggests, are conjoined epistemic phenomena, each predicated on gaps in knowledge. It is just such an epistemic problem—specifically a loss of legal and moral clarity—that this study explores through the lens of “normative ambiguity.”

Third, this article places futurity scholarship (e.g., Beckert Reference Beckert2016; Miyazaki and Swedberg Reference Miyazaki and Swedberg2017) within the broader sociology of time and “projectivity” (e.g., Auyero Reference Auyero2012; Tavory and Eliasoph Reference Tavory and Eliasoph2013; Frye Reference Frye2012; Mische Reference Mische2009, Reference Mische2014; Schwartz Reference Schwartz1974, Reference Schwartz1975), drawing on their combined resources to explain the criminogenic scene that developed when the once-synced temporalities of the Venezuelan state and the Venezuelan middle class came unglued under protracted crises. Finally, whereas works on futurity and legality tend to spotlight poor and working-class actors’ ties to illicit economies, this article foregrounds middle-class subjects, thus bridging such works with comparative studies of middle classness (e.g., Caldeira Reference Caldeira2001; López and Weinstein Reference López and Weinstein2012; Parker and Walker Reference Parker and Walker2013).

In the following pages I discuss the theoretical frame of the argument, focusing on the epistemic facets of the futurity-legality nexus. I then describe the interview data, documentary sources, and analytical strategy that are this study’s foundation. I then offer a three-part case analysis, revealing: the historical and institutional roots of “normative ambiguity” in Venezuela; interview respondents’ accounts of their threatened futurity; and why Stanford seemed able to restore a sense of futurity to its customers. I conclude with some observations about the broader implications of “normative ambiguity” for studying futurity.

Futurity and Legality As an Epistemic Problem

When grappling with the future, people often lean on familiar legal and moral certainties—but what happens when these break down? I answer this question by examining the loss of legal and moral clarity middle-class Venezuelans felt from the late 1970s to the 2000s, and offer a new take on how “futurity” and “legality” relate. Over those decades, a “normative ambiguity” around legality and licitness took hold in Venezuela, and in the course of trying to actualize their hopes, my middle-class respondents fell victim to fraud.

The ambiguity was manifold. During that period, they had ever more reasons to doubt the future worth of their currency and the legal implications of acquiring dollars; the competence and probity of Venezuela’s economic stewards; the integrity of their governing bodies; their country’s overall political direction; and, even their own civic standing. In some cases, the loss of certainty went alongside a quasi-“illegalization” of such institutions; for instance, a growing sense that Venezuela’s scandal-prone judiciary and monetary policies were tools for elite graft. Toward the end of this study’s focal period, middle-class Venezuelans were themselves symbolically “illegalized,” disparaged as enemies of “el pueblo.” Yet as certainties slowly gave way to doubt, Venezuelans continued to project and work toward life goals, relying on their domestic institutions when necessary and mitigating their harms when possible.

Futurity, Legality, Illegality

It is a truism of futurity scholarship that the “fictional expectations” of capitalist modernity (Beckert Reference Beckert2016) ultimately rest on a statecentric legal and institutional bedrock. To plan a future, moreover, is to assume that key features of one’s lifeworld will persist. Even workaday hopes for financial improvement entail not just practical but affective investment (Pixley Reference Pixley2004; Miyazaki and Swedberg Reference Miyazaki and Swedberg2017) in such continuity. Less clear in extant research is how we should interpret cases where plainly “licit” plans for the future endure despite their institutional supports having weakened.

Certainly, “illegal” practices and “illegalized” populations are often sites for hopes and plans that mirror those of “straight” society. Illicit economies, no less than licit ones, boast rules, order, and predictability (Beckert and Dewey Reference Beckert and Dewey2017; Panella and Thomas Reference Panella and Thomas2015: Roitman Reference Roitman, Comaroff and Comaroff2006)—key ingredients of future-thinking. Indeed, even when hostile to their aims, the state itself can offer illicit economic actors valuable clarity and predictability. Focusing on ambiguity, this study illuminates the obverse case: situations in which the “official” supports of future-thinking fall into discredit, yet people maintain and pursue licit goals, though epistemically and institutionally set adrift. What is more, the study shows how Venezuelans’ pursuit of licit goals within such a context left them vulnerable to criminal schemes.

The focus on normative ambiguity also sheds light on the links between futurity and illegality. In her comments on Beckert’s Imagined Futures, Harrington exhorts scholars to treat economic futurity and deception as inherently, rather than casually, linked (Reference Harrington2017). Both capitalism and fraud, she argues, depend on confidence, on stoking people’s sense of possibility toward an unknowable future. The conditions that feed ordinary economic futurity thus also nourish illegality. Upstanding and fraudulent business alike depends on inspiring customers to take leaps of faith and make often unwarranted projections (Balleisen Reference Balleisen2018). Normally, though, such leaps find their footing in the underlying institutional order. Trust in courts, legal tender, or regulatory regimes can blunt our anxiety before the unknown and give us greater license to imaginatively jump from today to a far-off tomorrow.

Futurity and fraud thus are not just epistemically similar, but both lean on institutional assurances. A gradual loss of such assurances—a slide into normative ambiguity—left Venezuelans in a bind. But as futurity research suggests, the impulse to hope and plan is deep-seated. Skeptical of their institutions yet fixated on their futures, my middle-class respondents sought a way forward. And Stanford appeared to restore to them some of the assurances and forms of validation they had been stripped of, piecemeal, over the preceding two decades. In times of normative ambiguity, my data show, our heightened need for assurances spells opportunity for fraudulent actors.

Futurity and the Sociology of Time

This article combines tools from futurity scholars and the wider sociology of time to show how normative ambiguity put those respondents at risk. Recent futurity research suggests that vast amounts of institutional and cultural work are required to establish and sustain our future-directedness in capitalist modernity (Beckert Reference Beckert2016; Miyazaki and Swedberg Reference Miyazaki and Swedberg2017). What is more, our hopes are a valuable resource that a range of institutional actors battle over to shape, such that “those who successfully convince investors of a specific future are the victors” (Beckert Reference Beckert2016, 156).

Beckert points to competition and the provision of credit as capitalist futurity’s main pillars. Within these, lenders, securities markets, entrepreneurs, consumers, prognosticators, and economic theorists help form futurity’s framework. None, however, is more vital than the state, with its influence on the money supply, its regulatory tools, and its power to enforce property rights. Beckert’s dazzling book maps the practical and cognitive bases of future-thinking but leaves futurity’s normative dimensions mostly uncharted. This is particularly true of the state. In a given society, the state helps reify the idea of belonging to a community of fate, forging its members’ collective sense of futurity. Through countless institutional means, the state also props up its members’ individual hopes. It not only shapes their views on what sorts of futures are valid and feasible but also provides or withholds key means for achieving them. Such state supports, thus, are not neutral but instead normatively charged.

Accordingly, this study focuses on futurity’s normative bases. The life course under capitalism is often practically and culturally financialized: middle-class subjects in particular are made to feel an obligation to their future selves that asserts itself as a present imperative to make prudent but profitable choices. To be effective, such private obligation depends on a deeper set of guarantees that ordinary people can see and lean on. The state extends such guarantees by issuing currency, regulating economic life, and enforcing laws. The case below shows what can result when such guarantees are established, then later withdrawn. In the 1960s and 1970s, Venezuela seemed a wealthy, institutionally modern country, and its middle and upper classes embodied the futurity Beckert and others describe. In later years, state institutions fell into decline and disrepute, muddling the relative legal and moral clarity Venezuelans had previously enjoyed. Though futurity’s supports withered, Venezuelans’ sense of duty to their and their dependents’ future selves remained. That disjuncture put my respondents at risk. To grasp why requires that we reach beyond recent works on futurity to the broader sociology of time, with its insights on time’s subjective and relational aspects.

Drawing on phenomenology, sociologists have outlined the layered structure of temporal experience. Specifically, they identify three imperfectly nested time scales that, given the right conditions, can come into conflict. The broadest scale consists in “temporal landscapes,” rigid forms of social time “that actors experience as inevitable and even natural” (Tavory and Eliasoph Reference Tavory and Eliasoph2013, 909). This includes clock and calendar time, institutional cycles (e.g., semesters or fiscal years), the fixed sequence of educational and work careers, and the expectations that attach to different points in the lifecourse. The concept covers, too, my respondents’ notions about the “natural” arc of a middle-class life (a university degree, employment, marriage, child rearing, and retirement) and the practical and financial requisites pegged to each stage.

At the next scale rest individuals’ plans or “projects” (Mische Reference Mische2009, Reference Mische2014; Tavory and Eliasoph Reference Tavory and Eliasoph2013), their consciously articulated goals, products of “creative as well as willful foresight” (Mische Reference Mische2009, 697). The concept of “protention,” the third category, names our unconscious “moment-to-moment anticipation” of the immediately forthcoming (Tavory and Eliasoph Reference Tavory and Eliasoph2013; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Hassard1990, 225–26): for instance, the unthinking way we round a familiar street corner, or how we prime our fingers to tap in our personal code after feeding our debit card into the bank teller machine, so accustomed are we to that familiar sequence. In normal times, our “projects” take for granted broad swaths of the “temporal landscape,” treating its features as unproblematically fixed. And our “protentions” remain at the level of unconscious practical reason (e.g., Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice2000, 206–13). In the following pages, however, I argue that such “normal times” rest on unseen supports—a stable normative basis—and I show how a loss of legal and moral clarity can place the foregoing time scales into tension and make their cloaked features visible.

Middle-Classness and Futurity

Sociologists of time also reveal time’s relational character, in particular how time can be a medium and measure of power. Economic and political domination often take temporal forms, such that society’s weaker members not only must “wait on” the more powerful, whose time is ascribed greater value, but see own their ability to hope and plan curtailed (e.g., Auyero Reference Auyero2012; Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Nice2000, 221–31; Schwartz Reference Schwartz1974, Reference Schwartz1975). A broad middle range, though, lies between Bourdieu’s “subproletarians” (Reference Bourdieu and Nice2000) or Auyero’s “patients” (2012) and the elites on whom most others wait. Under capitalism, the middle classes exemplify a future orientation defined as much by necessity as by an affective investment in the rules of the game.

As my data reveal, theirs is a precarious “projectivity” (Mische Reference Mische2009), sensitive to disturbances in the underlying normative order. Thus, when my Venezuelan middle-class respondents saw a host of legal and moral certainties cast into doubt from the late 1970s to the 2000s, and with them their paths toward desired futures, they experienced that shift as a time-based status demotion, a feeling that the relevant institutions were now hostile to rather than supportive of their hopes.Footnote 2 Though their aspirations barely changed, their sense of their place in the world was transformed. Their resulting insecurity would leave them vulnerable to fraud. As Frye shows (2012), projectivity boasts an expressive dimension. It is partly through our hopes and the steps we take to achieve them that we signal our present moral worth. When prolonged crisis lessened the likelihood of realizing their hopes, my middle-class respondents were left hungry for precisely the sorts of fixes Stanford offered: services that flattered their sense of past and present, and financial tools for reaching desired futures.

Data and Methods

In 1986, the eponymous R. Allen Stanford, a bankrupt Texas fitness club mogul, founded an offshore bank on the tiny Caribbean island of Montserrat. Forced to neighboring Antigua four years later, Stanford International Bank (SIB) spent its first decade hawking its signature product, a certificate of deposit, or CD, to Latin American clients.Footnote 3 It marketed the CDs through several Texas- and Florida-based “representative offices” to create the appearance that SIB was but one piece of a US-based whole. By the late 1980s, the Stanford Financial Group, as the conglomerate came to be known, was doing brisk business in the crucial market of Venezuela, where it would launch a stock brokerage tasked with selling the CDs, and a commercial bank. Dollar-denominated and plausibly “American,” Stanford’s CDs offered interest rates two to four points higher than equivalently-termed US bank CDs. In addition, Stanford claimed that its CDs were backed by a “globally diversified portfolio” of liquid securities. Instead, new deposits were used to cash out previous investors.

Data for this article come primarily from 54 interviews conducted in the Venezuelan cities of Caracas, Mérida, and Valencia, in late 2010. I interviewed three categories of respondents. The first and largest group were defrauded middle-class Stanford investors (42 interviews with 44 respondents), nearly all of whom invested between 2001 and 2008.Footnote 4 The second consisted of Stanford employees (5 financial advisers from its Venezuelan brokerage and one employee of its commercial bank). The third group was a miscellany of lawyers, financial services professionals, and others with links to the case (totaling 6). Interviews with investors and ex-employees probed respondents’ educational and professional arcs; their experiences and ideation around money and investment; the sequence that led to their hearing of and transacting with Stanford; their interactions with Stanford and its personnel for the relationship’s duration; for investors, the significance and composition of their investment; and their coping strategies in the fraud’s aftermath.

Aside from two I conducted on the phone, all interviews took place face to face at locations of respondents’ choosing (mostly eateries, workplaces, and homes) and tended to last about 1.25 hours. All but one of my interviews with investors and ex–Stanford employees were audio-recorded. Once interviews were transcribed, I read through them and wrote holistic memoranda about each interviewee to produce interpretive anchor points for subsequent analysis. Using NVivo analytical coding software, I then performed several rounds of thematic coding until the narratives clustered into themes, some of which are detailed in the analysis.

The sensitive topic required that I secure multiple routes to my focal population. This helped mitigate network bias in subsequent “snowball” sampling. I recruited interviewees via six distinct entry points: a US-based law firm representing defrauded Venezuelan investors; a Europe-based law firm operating in Caracas; two unrelated, arms-length personal contacts; the head of a Venezuelan finance weekly; and a recruitment text posted to a then-popular financial fraud-themed Venezuelan blog. From these nodes, I used snowball sampling to reach more respondents. My credibility as a researcher was no doubt bolstered by my institutional affiliations and personal links to some defrauded investors. All interviewee names used below are pseudonyms. In addition to interviews, this work is informed by both scholarly and journalistic secondary sources on Venezuela during this period, US- and Venezuela-based court documents regarding Stanford, and US- and Venezuela-based print and television coverage of Stanford dating from before and after the fraud’s discovery.

The Onset of Normative Ambiguity: The Late 1970s to the 2000s

Following the 1958 coup that ousted the autocratic General Marcos Pérez Jiménez from power, Venezuela’s three main political factions forged the Puntofijo Pact, an agreement meant to stabilize and legitimate Venezuelan democracy. Puntofijo, as the period came to be known, soon settled into a two-party power-sharing scheme between the social democratic Acción Democrática (AD) and the Christian democratic COPEI.Footnote 5 In late 1973, 15 years into this experiment, a sudden tripling of oil prices “created the illusion that instantaneous modernization lay at hand” (Coronil Reference Coronil1997, 237). That December, Carlos Andrés Pérez, a charismatic populist from AD, was elected president, vowing to channel the flood of petrodollars toward building what he dubbed Gran Venezuela. Flush with cash and a congressional majority that let him rule virtually by decree (Gil Yepes Reference Yepes and Antonio1992, 294–96), Pérez oversaw “dazzling modernization projects that engendered collective fantasies of progress” (Coronil Reference Coronil1997, 239).

In the short term, the tide of petrodollars, and with it Venezuela’s overvalued currency, the bolívar, would lift countless Venezuelans into the middle class, affording them previously undreamed-of consumer comforts and freedoms. As reflected in both popular and scholarly accounts, this mid-to-late-1970s abundance would spawn the apocryphal figure of the ‘ta barato, middle-class Venezuelan travelers “who went crazy in Miami’s malls,” so giddy at the bolívar’s buying power that they’d exclaim, ¡‘ta barato, dame dos! (that’s cheap, give me two!) (Márquez Reference Márquez2003, 199; Almandoz Reference Almandoz2004, 90). So strong was the bolívar, one interviewee jokily reminisced, that “you would go to Miami for anything. You’d go to Miami to buy a candy bar” (Interview, 12-08-2010, No. 1).Footnote 6 Miami merchants, another insisted, even took payment in bolívares in those years (Interview, 11-23-10, No. 2). In sum, Gran Venezuela, or more cheekily Venezuela saudita (Saudi Venezuela) (e.g., Sanin 1978; Almandoz Reference Almandoz2018), connoted for my respondents a time of woozy affluence and expanded horizons.

Pérez’s infrastructure and nationalization spree helped gird the myth of Venezuelan exceptionalism, the idea that Venezuela’s democratic and technocratic institutions were superior to its neighbors’. (Indeed, scholars would parrot this claim until the late 1980s [Ellner and Tinker-Salas Reference Ellner and Tinker-Salas2007, 5–8].) Nearly from inception, though, Gran Venezuela sowed its own delegitimation. The influx of oil money, exceeding the government’s capacity to profitably allocate it (Hellinger Reference Hellinger2003a; Mommer Reference Mommer2003), led to a hypertrophy of state institutions, a metastasis of AD’s and COPEI’s clientelist machinery, and a normalization of corruption (Coronil Reference Coronil1997; Pérez Perdomo Reference Pérez Perdomo1996). By 1978, the debasement of Venezuela’s law enforcement and judicial sectors was a point of collective chagrin (Coronil Reference Coronil1997, 321–60). Nevertheless, and despite a burgeoning recession, the middle class would enjoy at least the appearance of bounty until February 18, 1983, when Pérez’s successor, Luis Herrera Campins, imposed a sudden devaluation of the bolívar, from 4.3 per dollar (where it had been pegged since 1964) to 7.5, while instituting a differential currency exchange scheme and anti–capital flight measures.

Viernes Negro, as that date would soon be known, marked a “shift of the collective consciousness” (López Maya Reference López Maya2005, 54), sparking “not only a material but also an ideological crisis from which the country never recovered” (Hellinger Reference Hellinger2003a, 27). At a brightly lit cafe in the Baruta borough of Caracas, Mario Napolitano, an IT specialist in his early 60s, narrated to me his financial past. When describing how he’d picked a particular bank in the mid-1980s, he recalled: “What attracted me was the prospect of not saving in bolívares but of investing, of saving, in a currency that was a bit more solid …, because by then in Venezuela, we’d had Viernes Negro.” Pressed to explain, he said:

[Viernes Negro] really showed that in Venezuela we didn’t have a sense for why people, [like] the Chileans that came here in those years [fleeing] political-economic problems, of why they calculated everything in dollars. We didn’t understand so well in Venezuela what a devaluation actually was. We weren’t [yet] even that hard hit by inflation…. But Viernes Negro made us really see that … you could lose a large percentage of what you’d saved … from one moment to the next. That is, it wasn’t even gradual but rather the government just decreeing a devaluation, and overnight you lose [a huge portion of it]. So, that awareness led me to only have investments in Venezuela like my house or other properties, but to save abroad, because I lost trust in the country…. I saw that politicians were no longer, … I started to see that the government, or the governments, of Venezuela, could once again—once I grasped what a devaluation really was—that they might once again utilize devaluations any time … they found themselves in liquidity problems. (Interview, 12-03-10, No.1)

Though couched as personal epiphany, Napolitano’s words echo those of many other respondents. Fiorello Ascari, a similarly aged scion of a small construction firm, described Viernes Negro as “when we realized that our country was no longer what it had been,” that “one could no longer trust in Venezuela” and should thus “send anything we earned abroad” (Interview, 10-18-10, No.1). Moreover, Napolitano expresses key themes. First, in alluding to the struggles of Chileans (and, implicitly, countless other South Americans in those years who took refuge in Venezuela), he flashes the exceptionalist mindset typical of the petroboom “golden age,” Venezuelans’ belief that they were institutionally immune from the ills that plagued the continent. Invoking the trope of trust betrayed, he also depicts the state and its politicians—irrespective of party (“or the governments”)—as scheming opportunists against whom middle-class citizens had now to safeguard their interests. As such, Napolitano paints Viernes Negro as the moment when state economic policy stopped serving the middle class and emerged instead as a source of anxious uncertainty.

If Viernes Negro was a late reckoning with the failings of Gran Venezuela, the years that followed cast the whole Puntofijo project into doubt. The middle class would shrink drastically from the mid-1980s through the 1990s (Hellinger Reference Hellinger2003a, 38; Villegas Reference Villegas, Jeffrey and Tognato2018, 127), with double-digit inflation sapping its “purchasing power, quality of life, and hopes for improvement” while seeding “mutual distrust and conflict among all economic actors, with particular discredit falling on the state and ruling regime” (Kornblith Reference Kornblith1998, 22, 23). Simultaneously, the “privatization of the legal process” (Coronil Reference Coronil1997, 343), evident since the late 1970s, continued apace with the sorting of the courts and powerful law firms into party-allied and bribe-seeking “judicial tribes” (Ojeda Reference Ojeda1995). When, in early 1989, Carlos Andrés Pérez (granted an improbable second presidency) announced his paquetazo of austerity and liberalization measures, the country exploded into nine days of protests, looting, and state reprisals that, as Margarita López Maya writes, “established violence as a permanent fixture in [Venezuelans’] lives” and augured a broad upsurge in street crime (2005, 41, 42–44). The Caracazo, as that episode is now known, extinguished Puntofijo’s legitimacy.

For “a country accustomed to celebrating its social harmony, however illusory” (Coronil Reference Coronil2011, 34), the restive 1990s proved an odd and painful interregnum. Suddenly, social groups sidelined by years of oil-fueled partidocracia—workers’ movements, the middle and technocratic classes, and the military—vied for renewed influence (Hellinger Reference Hellinger2003a; López Maya et al. Reference López Maya, Smilde and Stephany2002). A pair of coup attempts in 1992, including a failed but galvanizing putsch by Hugo Chávez, portended what would come. Around that time, the private sector emerged as the new engine for elite graft (Coronil Reference Coronil1997, 380–82). Already stung by revelations that “plugged in” businessmen had bled roughly US$50 billion from the country’s coffers via the differential currency exchange scheme founded in 1983 (Beroes Reference Beroes1990), Venezuelans now found themselves the direct victims of such games, as when the 1994 collapse of the country’s second-largest bank (itself a Ponzi scheme) nearly cratered the entire banking sector (Vera Reference Vera2000). Such events would broaden the scope of popular discontent from the state to the business community (Gates Reference Gates2010).

From Viernes Negro until the late 1990s, the middle class thus saw its legal and moral certainties swept by doubt. Monetary policy switched from protective to predatory in an instant. Venezuela’s vaunted two-party democracy was unmasked as a venal cartel. The legal system, too, was exposed as a pay-to-play minefield. And as inflation and crime chipped away at the nation’s “polyclass” mythos (Villegas Reference Villegas, Jeffrey and Tognato2018), the shrunken middle class itself became an object of scorn.

Hugo Chávez’s electrifying rise to power in 1998 enjoyed appreciable middle-class support, but the relationship would curdle by 2001, as the bulk of that class allied itself with recalcitrant oil workers, business elites, and the formal political opposition (López Maya Reference López Maya2005). After beating back a coup in 2002 and a massive strike at the state oil company months later, Chávez sharpened his rhetoric toward the middle class. While co-opting and dismantling Puntofijo’s institutions, he promoted a Manichaean discourse that, among other tactics, symbolically coded the middle class as outside “el pueblo,” politically and morally suspect (Mallen and García-Guadilla Reference Mallen and García-Guadilla2017; Villegas Reference Villegas, Jeffrey and Tognato2018). It was in this broad span (2001–2008) that the bulk of my respondents would cross Stanford’s threshold.

Futurity Unmoored: Middle-Class Venezuelans Planning Against the State

For these respondents, the foregoing crises provoked normative ambiguity, the sense that Venezuela’s legal-cum-moral institutions had come unmoored. This would drive a wedge between the state and the temporal orientations of those subjects. To trace this process, I borrow from the sociology of time and futurity. The concept of projectivity (Mische Reference Mische2009) is especially apt for grasping and dramatizing this split. Existing studies suggest that middle-classness involves a fraught relationship to time and planning (e.g., O’Rand and Ellis Reference O’Rand and Ellis1974; Zaloom Reference Zaloom2019). In contrast both to the poor, whose precarity locks them into short-termism, and elites, whose wealth affords them a temporal margin for error, the middle class must continuously prepare if they are to preserve their status and comforts. As a genre of activity, middle-class financial planning thus approximates what Mische calls “sites of hyperprojectivity” (2014, 437), settings in which possible futures are consciously considered and means for attaining them are sifted.

In my interviews, defrauded Stanford customers, most of them at or near retirement, recalled the “projects” that had shaped their investing arcs. Their goals were standard middle-class fare and fairly uniform. They had sought to provide for themselves into advanced old age, so as not to encumber loved ones with their upkeep and medical costs. Moreover, they had hoped to save enough to put their adult children on sure footing; for instance, by paying for their education, helping them purchase first homes, or leaving them modest inheritances. A few voiced the desire to indulge in creature comforts or a bit of travel. All evinced some concern with the “temporal landscape” (Tavory and Eliasoph Reference Tavory and Eliasoph2013), rigid features of the institutionalized lifecourse that posed financial snags, such as marriage, having and raising children, or caring for ageing parents.

The most obdurate feature of this landscape, though, was the finite length of a typical work career. Respondents were keenly aware that retirement marked the probable end of their earnings and thus the point by which they had better secure old age independence. Missteps could be ruinous. As Andrea Sáez, a retired accountant for an oilfield services firm, lamented: “It’s too late for me now. And at this stage, and in this country, getting a job … is not feasible. I had my savings … and they slipped from my hand…. It wasn’t too much money…. But it was enough for me to live, I don’t know, eight years, ten years, comfortably” (Interview, 11-19-10).

This stock middle-class burden—anxiously squaring one’s earnings outlook, familial duties, desired lifestyle, and life expectancy—was made more onerous for my respondents by their context. When charting and working toward goals, one hopes that the relevant institutions will be, if not outright supportive of, then, at least neutral to one’s aims. Yet middle-class Venezuelans felt themselves beset by institutions, public and private, they saw as practically hostile to the realization of their projects. As a result, their approach to planning took on a distinctly oppositional cast. This is best illustrated by their reflections on Venezuela’s currency and legal climate.

When discussing money, my respondents invariably cited the bolívar’s record of inflation and devaluations. Luis Antonio Rigau, a financial manager for a foreign industrial firm in his early 40s, recounted how he had opened a dollar-based account in the early 2000s after saving a modest sum. When Citibank turned him away for not meeting its US$25,000 minimum, a friend of a relative pointed him to Stanford, whose account minimum was $10,000. Though Rigau’s ultimate aim had been to save a down payment for a house, his more proximate goal had been “to save in a hard currency, in dollars. Because with the inflation in Venezuela it makes no sense to save even one bolívar…. Only people who don’t grasp inflation do that…. But not everyone has $10,000” (Interview, 10-18-10, No. 2). Others spoke in near-identical terms. They contrasted the bolívar with the “hard” dollar, denounced it as “unstable,” and likened its value to “sand” or “water,” as through a sieve. Indeed, because the bolívar was such a poor vessel for value, the respondents constantly sought other places to store, and ways to preserve, the fruits of their labor.

Their efforts took many paths. Most opened dollar-based bank accounts at some point, in Venezuela or the United States. Some invested in dollar-denominated securities through local or foreign brokerages. A handful bought apartments abroad, primarily in South Florida. The vast majority, though, invested their savings in some form of domestic fixed asset, such as their family home, a rental property, a small business, and even their automobile. The constant and haphazard struggle to protect their earnings from inflation imbued their long-term projects with uncertainty while subtly warping the shorter term.

Though extreme, Virginia Márquez’s arc is illustrative. When we met, she was about 60 and had lived many lives: primary school teacher, lawyer, business consultant, and proprietor of several ventures, including an imports firm, an auto parts company, and last, a preschool. Her businesses—through which she had hoped to preserve and build on her capital—had mostly flopped. This tireless entrepreneurialism extended to her life “off the clock,” in which she had, over the years, bought and sold a dizzying number of apartments and cars to build up her nest egg. When we spoke, she was living on a pair of bolívar-denominated pensions, worried that these alone would not sustain her into old age (Interview, 10-21-10, No. 1).

Coveted oil industry pensions fared no better under inflation. Tomás Gómez, a retired “technical executive” with PDVSA, had left that firm in early 2000. “It was a good pension,” he recalled, that at first “permitted me a certain comfort. [But, i]t’s been five years since they raised [it for inflation] … because the government thinks PDVSA executives earned too much” (Interview, 10-25-10, No.2). Without their Stanford returns, Gómez and his wife were living spartanly, unable to fix their truck’s air conditioner. Faced with chronic inflation, these middle-class respondents, even those with nominally good pensions, could ill afford to anchor their plans in their country’s currency. Having constantly to navigate this challenge gave their projectivity a frenzied, oppositional character.

Deepening their unease about the future, my respondents also felt threatened by Venezuela’s legal climate. Indeed, it was precisely their attempts to seek refuge in the US dollar or domestic fixed assets that exposed them to state institutions they perceived as hostile to private property and lacking in due process. Their preferred term for this was inseguridad jurídica, or legal insecurity. Many interviewees invested with Stanford after 2002’s failed coup, the 2003 oil strike, and the opposition’s failed 2004 recall referendum, when Chavismo’s rhetoric toward middle-class Venezuelans grew especially caustic (Mallen and García-Guadilla Reference Mallen and García-Guadilla2017; Villegas Reference Villegas, Jeffrey and Tognato2018). In 2008 Alejandra Masri, a widow in her early 60s, inherited a moderate sum, her share from the sale of family-owned land. She considered buying domestic real estate before her brother turned her on to Stanford: “I wanted to invest it, but that the money not be in Venezuela, for reasons that are more than obvious: the situation the country is in, the danger [we face] from a legal point of view” (Interview, 10-11-10).

Luis Vásquez, a 30-something architect for an IT firm, made this common point more bluntly. Recalling his first time opening a US bank account in the early 2000s and his 2006 move to Stanford, he said,

It was important to me that Chávez not be able to just decide “let’s repatriate all these accounts” or “let’s access the names of everyone who has dollar-based accounts abroad.” … It was really important that if these banks were to go belly-up … that the process not be governed by Venezuelan law, [but] rather that the process actually work for me. For as long as I’ve had the use of reason, there hasn’t been “law” here. What we have here is the wielding … of power and influence—but not law (Interview, 9-24-10, No.2).

Another young respondent, late-30s logistics manager Jorge Rivera, said he had invested with Stanford in 2008 “to have that money someplace [the state] couldn’t touch it … [because of] the legal insecurity we face, where at any moment they might expropriate [what’s yours]” (Interview, 10-13-10). Reasonable or not, such feelings were partly a response to Chavista discourse that impugned the middle class as disloyal, quasi-criminal. As Guillermo Velasco, a retired human resources manager, grumbled, “this government thinks anyone with 100 bolívares in the bank is.. un escuálido, an imperialist pitiyanqui ” (Interview, 9-23-10).Footnote 7

Thus, these respondents felt their medium- and long-term projects threatened by legal institutions they viewed as corrupt and politicized. Their temporal sense was also vexed on the day-to-day “protential” scale (e.g., Tavory and Eliasoph Reference Tavory and Eliasoph2013) by another danger they blamed on the state: violent crime (Zubillaga and Cisneros Reference Zubillaga and Cisneros2001; cf. Ávila Reference Ávila2012). The beginnings and ends of interviews were often punctuated by respondents’ words of concern for my safety in Venezuela, backed by accounts of their own brushes with violence. An ex-Stanford financial adviser, Iván Soto, had twice been robbed at gunpoint by men on motorcycles while driving to work (Interview, 9-30-10). Matías Duarte, a 60-something ex–design and communications specialist for PDVSA, revealed that his son had been mugged five times (Interview, 12-04-10, No.2). The threat of kidnappings for ransom hung over many respondents, becoming a kind of risk benchmark: when Alejandra Masri described her Stanford investment, she said the sum was significant to her, if not quite enough “to make me kidnappable” (Interview, 10-11-10). Gabriel Oliveira, a retired oil industry accountant, recounted the recent kidnapping of his daughter’s brother-in-law and two friends and the pricey ransom it cost his family: “under these conditions, it’s really hard to imagine a future here. Really hard” (Interview, 12-04-10, No.1).

Counterfeit Futures: Normative Ambiguity and Vulnerability to Fraud

It was precisely by making a future more imaginable that Stanford lured so many Venezuelans addled by endless crises. The persistent uncertainty around the bolívar, key political-economic institutions, crime, and even middle-class Venezuelans’ civic standing formed the drab background against which Stanford seemed a beacon. The firm buttressed its clients’ future-thinking by appearing to offer it both practical and emotional supports. On the practical front, Stanford’s high-yield, dollar-denominated CDs promised a path out of the bolívar’s value trap and toward wealth accumulation. In addition, the firm provided informal ways for its clients to dodge Venezuela’s restrictive currency exchange laws. On the emotional side, Stanford offered a customer experience that not only served clients in the present but signaled respect for their pasts and kindled their hopes for the future.

The chief practical benefit Stanford offered its clients, what most roused their hopefulness, was a chance to dollarize their futures. Stanford’s Venezuelan brokerage pushed dollar-denominated CDs issued by its offshore affiliate, Stanford International Bank in Antigua, while touting the conglomerate’s US roots. The CDs’ interest rates were enticing but not so high as to alarm prospective clients. Projected over the long term, though, the generous rates promised a way not just to save but, via compound interest, to accumulate wealth in the world’s reserve currency. To be sure, most interviewees had already begun dollarizing their plans by the time they learned of Stanford. Many had long before opened US or otherwise dollar-based bank accounts. Some had done so during trips abroad, while others did so domestically at one of the many foreign banks operating in Venezuela, during intermittent periods (pre-1983, 1989–94, 1996–2003) of free currency convertibility (Palma Reference Palma2020). A sizable swath of my respondents had worked for multinational firms that paid out bonuses or other benefits in dollars, direct-depositing these into foreign accounts. Indeed, what made Stanford attractive and legible was that it offered an in-demand product from within an established ecology and cultural framework.

Given the bolívar’s chronic double-digit inflation (International Monetary Fund 2019), a plausibly “American” firm peddling dollar-based investments was almost a sure thing. Middle-class Venezuelans constantly sought ways to trade bolívares for dollars and, when the need arose, to change them back. Describing his frequent dips into the black or “parallel” currency market, Luis Vásquez revealed the mundanity of money changing for his social stratum.

When you have a chance to sell dollars …, if you’re going to sell the dollars via wire transfer … you can ask for a bit more, because of the security and because it’s impossible to wire counterfeit dollars. And so, for instance, people will say “I can sell you these dollars … in cash and it will cost you 8.5 [bolívares per dollar], or I can wire it and it’ll cost you 9 or 9.5. In addition, I’m sure you’ve seen how the exchange rate is pretty variable, depending on social status, on the day …, on your degree of need …, or desperation, or ignorance of the market (Interview, 9-24-10, No. 2).

More wary of black market deals, Alejandra Masri described to me how she first expatriated dollars using a then-legal, brokerage-based bond transaction: “since we deal here with this currency exchange problem,” she explained, “you’re always kind of looking for ‘workarounds,’ I guess you’d say” (Interview, 10-11-10). Since both wages and pensions were nearly always paid in bolívares, the hunt for “workarounds” did not end once clients signed on with Stanford—and some Stanford personnel were happy to oblige. In an account corroborated by others, Virginia Márquez recalled how her Stanford adviser helped her offload bolívares by brokering trades with other Stanford investors.Footnote 8

I would tell her, “hey, I’ve got some bolívares…. I want to buy $1,000.” [She’d say] “Ah, okay Ms. Márquez, that’s no problem…. I’ll arrange it for you…. Sit tight while I find a good price, and I’ll call you back.” Then she’d call [saying] “Look, I’ve got a client that’s selling $1,000 [or] $2,000 [or] $500.” “For how much?” [I’d ask]. “For such and such amount.” “Great” [I’d say,] “I’ll deposit [the bolívares] and you buy [the dollars] for me” and she would transfer them to my account (Interview, 10-21-10, No. 1).

Such transactions, I should note, also took place at competitor firms. Still, the fact that clients were pleased rather than put off by their advisers’ willingness to skirt currency laws crystallizes this article’s argument. Not only had years of normative ambiguity instilled in them a form of “legal cynicism” (Sampson and Bartusch Reference Sampson and Jeglum Bartusch1998) toward such rules, it had made a virtue of breaking them. Against that backdrop, Stanford’s practical fixes to Venezuelans’ currency problems were an unqualified good, a boost to their efforts to realize their plans.

Yet what set Stanford apart was its attention to the emotional side of clients’ future-thinking. In ways large and small, Stanford offered its customers—people situationally conditioned to doubt their long-term prospects—reasons for optimism. First, Stanford allayed some of the everyday uncertainty that weighed on clients by tending to their need for convenience and safety. Second and related, it provided an aesthetic and customer-service experience unique in Venezuela that not only made clients feel that they had “arrived,” thus flattering their sense of past and present, but buoyed, too, their hopes for the future.

The cities where Stanford operated were traffic-snarled and crime-plagued. This was nowhere worse than Caracas, where I conducted most of my interviews. To shield clients from hassle and risk, and to ingratiate itself with them, Stanford offered pleasing amenities. It was periodically necessary for clients to sign account documents, as when it came time to renew a CD. Rather than ask them to make a cross-town trip, Stanford would often send motorcycle couriers or a private parcel service like DHL to deliver and retrieve paperwork. Wilfredo Balbo, a real estate broker in his 50s, described how routine this was: “‘Hey,’ I’d tell them, ‘I can’t make it over there.’ ‘All right, I’ll send [a] motorcycle over.’ I wouldn’t even need to give my address; they knew where my office was. They’d send the courier …, they’d bring the paperwork to me, and take it away [signed]. It was marvelous. I’d say to myself ‘I’ll never leave this bank’” (Interview, 11-22-10, No. 1). Other respondents, too, recalled using these delivery services to transmit documents, deposit checks, and even receive their monthly account statements.

In addition, interviewees praised the ease and safety afforded by Stanford’s online account portal. In the mid-2000s, many Stanford clients asked to stop receiving their paperwork through the Venezuelan post. By that time, kidnappings had become a subject of widespread concern, and several respondents had worried that their mail might be intercepted, their financial privacy breached, and their lives thus put at risk.Footnote 9 By allowing clients to send and receive documents by courier and to monitor their accounts online, Stanford quieted these fears. Indeed, such services were no mere frills. Middle-class Venezuelans’ sense of long-term wellbeing was eroded by “protential”-level threats and hindrances they perceived in their environment (Zubillaga and Cisneros Reference Zubillaga and Cisneros2001; Ávila Reference Ávila2012). By mitigating these, Stanford kept clients’ focus on their imagined comfortable futures.

The firm’s efforts, though, went beyond ensuring ease and safety to something deeper: a kind of status flattery that worked by a temporal logic. One after another, respondents described Stanford’s sumptuous offices—the dark wood, green marble, brass fixtures, the “elegant,” vaguely “English” old-world feel—and their effect on them. Though the splendor made some leery, many more recalled experiencing it as proof of Stanford’s heft, permanence, and success. Moreover, these signs of success not only reassured depositors but subtly stroked their egos. Jorge Rivera became a customer when a college friend was hired by Stanford’s commercial bank. Before then, though, he’d walked by their posh offices and assumed it was “an elitist bank where they probably required a large [minimum balance] to open an account, and [so] I’d never go in.” Recounting his early impressions as a client, he described how “the bank teller counters were wood with a marble slab top. The seats were leather. Usually there was no queue to deposit or withdraw money. And we Venezuelans see that as a plus…. And well, wow! You felt a certain social status when you walked in that bank—you felt important” (Interview, 10-13-10).

His take was echoed among the retirees who made up most of my sample. Across age groups, respondents described Stanford’s immersive opulence, as positively pleasurable, evidence not just of the firm’s success but, indirectly, of their own. In a setting where inflation constantly threatened to spoil the fruits of their past labors, such luxuries were potent signs to clients that their present status (and thus past achievements) merited recognition. They were also an invitation to hypostatize their sense of present security into a projected future.

But what most distinguished Stanford was its zealous approach to customer service, one geared toward dignifying clients by prioritizing their time. For my respondents the difference was stark. They described their previous financial institutions as embodying a specifically temporal disrespect. Snaking lines, foot-dragging service, elusive appointments, and shoddy automated phone menus were just some of their gripes. By contrast, Stanford advisers would visit clients at their homes or workplaces; take them out to meals; and meet on short notice and for long duration. As retired PDVSA executive Tomás Gómez put it,

The service was excellent…. I had a bit of experience with another [foreign] bank … [here,] Citibank. Every time I went there I had to request an appointment in advance, and they would [still] make me wait more than two hours. Frankly, the customer service was bad. It was always someone different…. There was no assigned adviser. Of course, the size of my deposit was very small, but occasionally I’d still need to go to resolve something. Well, whenever I went I had to do the whole “this is who I am, this is my account, and this is what I need.” It was always starting from zero, since they didn’t have a procedure where they’d look me up in the computer … [like] “let’s see your account; okay, here you are; here are the notes from your last transaction,” and such. Something that they did do at Stanford…. I had a really good experience there until this all happened (Interview, 10-25-10, No. 2).

Though his deposit was “very small,” Gómez felt he deserved decent service. For him, the delays, discontinuity, and disorganization he perceived at Citibank conveyed contempt, what Barry Schwartz calls “an assertion that one’s own time (and, therefore, one’s social worth) is less valuable than the time and worth of the one who imposes the wait” (1975, 856). Indeed, Stanford made its name inverting Schwartz’s formula. Omar Branco, a late 30s ex-Stanford financial adviser, described the job’s time demands as punishing. But, he emphasized, the firm’s service culture truly

was impressive…. We had clients who [only] had $10,000, and they could call any day, anytime—call me, not a secretary, me!—there were no roadblocks [between them and me] …, rather, if they called me on Saturday, I’d attend to them, no problem…. There were clients who had their money with us for the customer service, and they’d say “no one else offers this.” … [Or a client might say,] “look, I’ve got a problem, I need [to withdraw] $1 million right now!” and I’d call the [brokerage] president and say “I don’t care how, but this client needs to withdraw $1 million—not in the ‘five business days’ stipulated in the CD agreement—[but] right now,” and it would get done. Or [clients] would call me on a Saturday, 7AM: “I’m in Miami and my credit card’s not working,” and I would resolve it for them … no problem…. (Interview, 10-14-10, No. 1).

By appearing to honor their time, Stanford made even average depositors feel like notables rather than supplicants, something rare in Venezuela’s financial services sphere. Stanford thus offered clients not just a plausible path toward their desired futures but a pleasant, affirming one. Clients, in turn, invested themselves both financially and affectively in Stanford, entrusting their futures to that fraudulent firm.

Conclusions

The present case is not straightforwardly about “illegal markets.” To be sure, Stanford occupied a legal gray area, facilitating wealth expatriation and offering end-runs around currency laws. In this, however, it was joined by such lofty names as Merrill Lynch, Credit Suisse, and Citibank, as well as dozens of lesser-known financial firms. Such small-bore currency violations, moreover, were not just tolerated but most likely dwarfed by the pervasive and similarly condoned currency arbitrage schemes pursued by both Puntofijo-era and Chavista elites (Beroes Reference Beroes1990; Gulotty and Kronick Reference Gulotty and Kronick2020; López Maya Reference López Maya2018). It is thus truer to say that Stanford was a secretly fraudulent firm working within a practically “legal” and normalized sector of the economy. Even this phrasing, though, obscures precisely what drew thousands of Venezuelans to it: not the allure of the semilicit but the appearance of relative probity paired with the promise of gain. In Stanford my middle-class respondents saw a path around Venezuela’s dubious institutions and toward their desired futures. As such, the notion of “illegality” inheres as much in what they sought to escape as in the fates they ultimately met. Yet what can we learn from the fact that Stanford duped them by seeming to offer not just a comfortable retirement but a portal to a more trustworthy institutional sphere?

This article has framed the crossroads of futurity and legality as an epistemic matter. Extant scholarship takes for granted the centrality of state-capitalist institutional orders to the flowering of future-thinking. Thus, it is plainly worthwhile to ask how futurity and hope function in the context of outlawed and furtive economic markets. I have taken a different tack, however, asking whether ambiguity in such institutional orders might itself shape people’s futurity in ways that could expose them to predation. Specifically, this study has explored how a gradual loss of legal and moral clarity in Venezuela—a slide into “normative ambiguity”—helped prime my respondents to take a criminal firm’s bait. After seeing their institutions shrouded in doubt over many years, Venezuelans developed a harried, oppositional sort of futurity that regarded these institutions as threats rather than supports. Stanford exploited this reactive futurity expertly, using dollarized investment products and claims of US provenance to create the mirage of a safe passage to old age security, and by crafting a customer service experience that flattered clients’ sense of self, temporally integrating their pasts and projected futures in a pleasurable, affirming present.

The foregoing analysis has clear limitations, and its goals are modest. I do not claim that normative ambiguity is necessary or sufficient for fraud to develop. Even within the bounds of this case, my findings are limited to the middle rungs of the population. Hope is a stratified phenomenon (Swedberg Reference Swedberg and Miyazaki2017), and what my respondents viewed as some of the worst years of institutional uncertainty—Chavismo’s first decade—huge swaths of Venezuela experienced as a long-awaited democratization of institutions and restoration of hope (Márquez Reference Márquez2003).

I have not aimed to furnish insights that apply universally to the study of futurity. Instead, I have used Stanford’s fraud to illustrate the profit of framing the futurity-legality nexus as an epistemic problem. Subsequent studies of that nexus might thus find the following two questions analytically generative (whether the focal activities are legally permitted or proscribed): Was the institutional setting a source of security or uncertainty to respondents, and with what practical effects? And, did that setting confirm or undermine their sense of being morally valued members of the polity?

An additional path is hinted at in the transnational tilt of my respondents’ hopes. In their introduction to this special issue, Dewey and Thomas ask whether “illegal markets offer something other than a deepening relationship to hope-generating machines.” Though it sidesteps this question, this article shows one possible outcome of when such “hope-generating machines” cease to function. When their domestic institutions failed them, my respondents’ hopes did not die but rather were imaginatively displaced onto a different “hope-generating machine” they deemed more trustworthy. A full rendering of futurity and legality’s complex interactions will have to take such transnational orientations into account. Given the deepening precarity of the region’s other middle classes (ECLAC 2020; McKinsey 2019), Latin Americanists might test these insights against similar cases of fraud elsewhere. Furthermore, Venezuelanists might consider whether and how the dynamics shown here prefigured the illicit entrepreneurialism of the Maduro years (Rosales Reference Rosales2019).

Conflict of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.