Private health insurance has been a constituent part of the Dutch health system since the early 20th century. Before the major reform in 2006, almost a quarter of the population held so-called pure private health insurance cover as a substitute for sickness fund cover. The 2006 Health Insurance Act created a single, mandatory health insurance scheme covering the whole population under private law. One of its most important consequences was the abolition of the traditional division between statutory health insurance operated by sickness funds and all other insurance schemes including substitutive private health insurance with experience-based underwriting. However, the newly created scheme is not a pure private arrangement (the term ‘pure’ will be explained later in this chapter) but one extensively regulated by the state to protect public interests including, among others, solidarity in health care financing and access to health care.

This chapter starts with a brief overview of the history of private health insurance in the Netherlands and its structure in the 1990s and early 2000s. The focus in the second part is on the 2006 reform and its consequences for the health insurance market. Developments in long-term care insurance are beyond the scope of the chapter.

Private health insurance before the 2006 reform

Historical origins

The history of health insurance in the Netherlands dates back to the 19th century and is closely related to the rise of the medical profession and the advance of modern medicine. At that time, many workers could not afford to pay for health care and were dependent on charities or local governments in case of illness. Another problem was the absence of income protection in case of illness. To improve social protection, labour unions, guilds, employers, and municipalities established voluntary sickness funds (ziekenfondsen) covering only a few medical services including family medicine, some specialist care, maternity care and pharmaceuticals. By the beginning of the 20th century, about 10% of the population was affiliated with a sickness fund. This percentage had climbed to about 38% at the eve of World War Two (Reference Veraghtert and WiddershovenVeraghtert & Widdershoven, 2002; Reference KompanjeKompanje, 2008).

Under strong pressure from the Medical Association (established in 1840) sickness funds only accepted people with low incomes. People who did not qualify for a sickness fund cover could purchase private cover on a voluntary basis. These voluntary schemes can be regarded as the precursors of private health insurance. Notice however that, strictly speaking, sickness funds too operated as private insurers in the early days of health insurance. In the absence of any state regulation they could set their own premium and benefits package. Furthermore, they were fully risk-bearing (no risk pooling). Nevertheless, there were also some differences between sickness funds and voluntary schemes. The former fulfilled a primarily social function and offered their clients a benefits-in-kind plan with community rating, whereas the latter used the cost-reimbursement model and experience-based rating (Reference De Bruine, Schut, Maarse and Mur-VeemanDe Bruine & Schut, 1990).

The first government intervention was the 1901 Law on Accidents (Ongevallenwet), which offered workers some financial protection against accidents in the workplace. Attempts to introduce legislation on health insurance and sickness leave aroused significant controversy, not only for economic reasons (for example, the financial crisis of the late 1920s), but also as the result of political factors. Employers were sceptical about the introduction of statutory health insurance because of their fear of high costs and its impact on the overall economy. Neither was the National Medical Association, the best-organized interest group at the time, in strong favour of statutory health insurance. Physicians were particularly afraid that it would jeopardize their professional and economic autonomy. The Association would only accept a public arrangement if each of the following conditions were met: there was free choice of physician; half of the seats in the sickness funds’ boards were reserved for physicians; and enrolment in sickness funds was limited to people with low incomes. Stimulated by the National Association, many physicians established sickness funds of their own. These physician funds proved successful and soon had more subscribers than other sickness funds (Reference De Bruine, Schut, Maarse and Mur-VeemanDe Bruine & Schut, 1990).

Health insurance legislation was not passed until 1941. Ironically, it was introduced by the German occupying forces. The Sickness Funds Decree (Ziekenfondsenbesluit) established compulsory cover for workers with incomes under a state-determined threshold. Others (such as self-employed or older people) could join a sickness fund on a voluntary basis. The rest of the population was excluded from sickness fund cover and had to rely on (voluntary) private health insurance cover (Reference KronemanKroneman et al., 2016). The key elements of the Decree were as follows: employers and employees paid an equal share of income-related contributions; the benefits package was substantially extended to include hospital care, nursing care in a sanatorium and dental care; full risk pooling among the funds was introduced; competition between the sickness funds was abolished; and the national government was placed at the top of the health insurance pyramid (Reference De Bruine, Schut, Maarse and Mur-VeemanDe Bruine & Schut, 1990).

The 1941 Decree marked the beginning of an era of centralization in health insurance, putting an end to the self-regulatory governance structure of the sickness funds in the pre-war period. However, it did not fundamentally alter the role of private health insurance. In fact, by introducing an income threshold, the Decree institutionalized the pre-existing division between the sickness funds and private health insurance. This separation would remain a constituent element of the structure of health insurance in the Netherlands until 2006 (Reference KompanjeKompanje, 2008).

Policy developments from the end of the Second World War to the late 1980s

After the Second World War there was broad consensus that the German arrangement needed to be replaced with new legislation on statutory health insurance. This again appeared politically troublesome, just as in the pre-war period. The workers’ associations and the Labour Party demanded a single national scheme, whereas the Medical Association, the confessional (religion-affiliated) parties and the liberals fought for voluntary arrangements combined with a mandatory scheme for workers with an income under a state-set threshold. The latter proposal was also supported by employers who feared the adverse effects of a single national scheme on the fragile post-war economy. The political conflict was eventually settled by the enactment of the Sickness Fund Act (Ziekenfondswet) in 1964, which in most respects codified the earlier Sickness Fund Decree of 1941. As it only provided compulsory coverage for workers with incomes below a defined income threshold, it preserved the pre-existing division between the sickness fund scheme and private health insurance (Reference KompanjeKompanje, 2008).

Another post-war event was the establishment, in 1957, of a specific sickness fund for older people with incomes under a state-set threshold. The (income-related) contribution rate and benefits package were set by the state, which also covered, together with the sickness funds, the yearly deficit between premium revenues and spending. A specific sickness fund scheme for self-employed people, known as the voluntary sickness fund scheme, had already been established during World War Two. Both specific schemes would later become a matter of financial concern.

In the pre-war period the market for private health insurance was heterogeneous. In the 1930s, there had been a rapid growth in the number of commercial and noncommercial insurers offering coverage of a number of health services or fixed lump sum pay-outs in case of hospitalization. After the war, many sickness funds, usually in collaboration with other funds, set up subsidiaries to penetrate the private market. The subsidiary funds offered benefits similar to those covered by the private funds, targeting former enrollees with incomes above the threshold who could no longer be affiliated with a sickness fund. They proved very successful because of their policy of open enrolment, lifetime cover and community rating. These arrangements radically differed from the principles of actuarial fairness applied by the so-called pure private insurers. It was not until 1947 that a private insurer guaranteed lifetime cover for its subscribers (Reference De Bruine, Schut, Maarse and Mur-VeemanDe Bruine & Schut, 1990).

The success of the subsidiary funds motivated commercial insurers to adapt their products by reducing the number of exclusions and introducing full cost reimbursement. The universal application of lifetime cover and the creation of a common risk pool for private high-risk subscribers in 1957 were further illustrations of the evolutionary convergence between the sickness fund scheme and private health insurance. However, the mix of open enrolment, unlimited cover and low premium rates did not prove to be a sustainable business model. After a few bankruptcies, the state introduced public regulatory oversight of all private insurers, including private health insurers, to protect consumer interests.

In the 1960s and 1970s, commercial insurers started to offer health plans with high deductibles, age-related deductibles and age-related premium increases. They also introduced a maximum enrolment age. In the early 1980s, they began to attract young self-employed people (until then mainly covered on a voluntary basis by the sickness funds) by offering age-related premiums, deductibles and other attractive arrangements.

This aggressive marketing strategy of private insurers further undermined the already weak financial position of the voluntary sickness fund scheme for the self-employed and prompted the state to intervene in the private health insurance market by the passing of the Access to Health Insurance Act (Wet op de Toegang tot de Ziektekostenverzekeringen, WTZ) in 1986 to be implemented by private insurers. The Act introduced a safety net by securing private cover for people who were not eligible for the mandatory sickness fund scheme and who could not purchase private health insurance cover for medical (pre-existing conditions) or financial (high premiums) reasons. Among other things, the Act included a government-defined benefits package and a flat-rate premium as well as open enrolment and full risk pooling. As the premium revenues did not cover all WTZ spending, people with private health insurance cover had to pay an annual surcharge to cover the deficit. The Act also enabled private insurers to transfer anyone aged over 64 years to the WTZ scheme. As a result, private insurers – the champions of the free market – were able to avoid incurring any financial risk for high-risk subscribers (Reference SchutSchut, 1995).

Another state intervention was to abolish the scheme for older people in 1986 because of increasing financial deficits (the share of expenditure covered by contributions declined from 39.4% in 1970 to 18.6% in 1985). All subscribers were transferred to the mandatory sickness fund scheme. To compensate sickness funds for the resulting over-representation of older people among their members, the government adopted a law that obliged private health insurers to pay a solidarity contribution to the sickness fund scheme (Reference SchutSchut, 1995).

The policy measures taken in the mid-1980s mark an important development in the health insurance market: private health insurance had gradually become the target of state intervention. Yet, many policy-makers felt that a more fundamental reform was still required. They considered the new legislation to be an emergency measure that only tackled some urgent financial problems but did not offer any structural solution. It was not until 2006 that a fundamental reform came into force. Before discussing this reform, first an overview of the private insurance market between 1990 and 2005 will be given.

The health insurance market between 1990 and 2005

Following the 1986 reform, there were three types of substitutive health insurance plans. First, a broad range of pure private health insurance plans. These were voluntary individual or group plans offering a variety of benefits packages, deductibles and eligibility criteria for people who could not enter the sickness fund scheme because their income was higher than the state-set income threshold. Premiums were flat but, to some degree, age-related. Insurers were permitted to reject applicants and exclude pre-existing conditions. Second was the WTZ scheme offering open enrolment and a standard benefits package for those not eligible for the sickness fund scheme. Third, there were a number of public health schemes covering local and regional government employees, the police force and fire brigade. The first public scheme dated from 1926. Public health schemes resembled the sickness fund scheme in many respects, in particular in terms of mandatory participation, income-related contributions and benefits package. However, as they fell beyond the scope of the Sickness Fund Act, they were seen as belonging to the private insurance market, which was of course highly confusing if not misleading terminology. The heterogeneous structure of the private insurance market explains the introduction of the term pure private insurance in the introductory section. Pure private insurance is a distinct category to be discerned from other substitutive so-called private schemes.

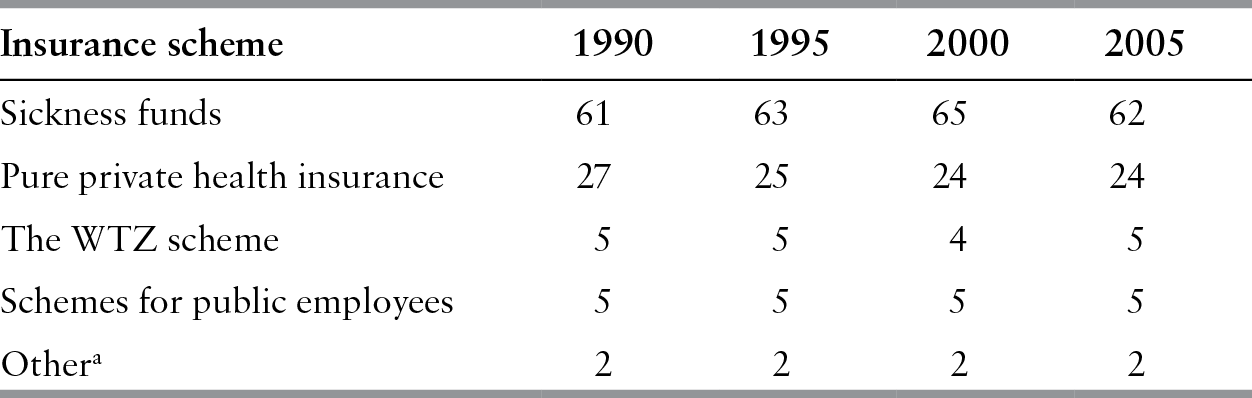

Between 1990 and 2005 the population shares of different health insurance schemes remained stable (Table 11.1), largely due to yearly adjustments of the income threshold for sickness fund eligibility. During the political debate on the Sickness Fund Act the government had appeased opposition from the private health insurance sector by promising to keep the share of the population covered by the sickness fund scheme constant. This agreement, known as the peace borderline agreement, remained in place until the 2006 reform.

Table 11.1 Health insurance population shares in the Netherlands (%), 1990–2005 (selected years)

| Insurance scheme | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sickness funds | 61 | 63 | 65 | 62 |

| Pure private health insurance | 27 | 25 | 24 | 24 |

| The WTZ scheme | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Schemes for public employees | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Othera | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

Notes: WTZ: Access to Health Insurance Act (Wet op de Toegang tot de Ziektekostenverzekeringen.

a Sector-specific governmental arrangements (e.g. covering the military).

Private insurers operated either as non-profit mutual funds or as for-profit companies. Private health insurers were precluded from involvement in the sickness fund scheme, but sickness funds were allowed to offer both substitutive and complementary private health insurance, but had to establish separate organizational forms for that purpose. The Sickness Funds Act prohibited any form of cross-subsidization from the statutory to the private sector.

Many employers contracted with a private insurer to offer a group plan to their employees. In 2005, 52% of those who were privately insured belonged to a group plan (Vektis, 2006). The private market was also characterized by higher switching rates than in the sickness fund scheme (15.4% of the privately insured switched in 2005 compared with 7.5% of sickness fund members) (Reference Laske-Aldershof and SchutLaske-Aldershof & Schut, 2005).

Per person annual health care spending was significantly lower among people with voluntary private insurance than among sickness fund members (€1357 in 2005 versus €1946), mainly due to the favourable risk profile of the former. However, administrative costs were higher for private health insurers (10.9% in 2005) than for sickness funds (4%) due to their smaller size, higher marketing costs and claim filing costs (Vektis, 2006).

With regard to provider payment, the key difference between private insurers and sickness funds was that the former paid general practitioners on a fee-for-service basis, whereas the latter applied capitation-based payment. Both types of insurers paid self-employed specialists on a fee-for-service basis. Traditionally, pure private insurers paid higher fees than sickness funds, but since the mid-1990s fees were similar due to central regulation (Reference LieverdinkLieverdink, 1999).

Gradually, private insurers also became closely involved in health policy-making. Following the corporatist tradition in Dutch health policy, their national association (set up in 1961) acquired a privileged status in health care price negotiations, alongside the National Association of Sickness Funds. In 1995, both associations merged to form a single national association, named Health Insurers Netherlands (Zorgverzekeraars Nederland), signifying the convergence of interests between sickness funds and private insurers.

Steps towards regulated competition

The Dekker Plan and its aftermath

The first steps towards the 2006 reform were made in 1986 with the establishment of the Dekker Commission, named after its chairman Dr W. Dekker, a former CEO of Philips. In 1987, it published its report Willingness to Change (Bereidheid tot Verandering), containing the outline of a new model for health care based on the principles of what was termed regulated competition. The report contained several radical proposals, including the abolition of the traditional division between statutory and private health insurance by integrating both types of insurance into a single mandatory scheme under public law covering the entire population. According to the Commission, the fragmented structure of health care financing proved to be an important source of inefficiencies and inequities. Central state planning was viewed as another source of inefficiency. To enhance efficiency, the Commission proposed a complex institutional framework in which market competition was to be strictly regulated by the state to prevent market failures and preserve solidarity in health care financing (Reference KronemanKroneman et al., 2016).

The Dekker Report received only a lukewarm reception and it took over a year before the government sent its proposal for new health insurance legislation – known as the Simons Plan, named after the then Deputy Minister of Health – to the parliament. This proposal, which deviated in several respects from the recommendations of the Dekker Commission, met with growing political resistance. Sceptical opinions were voiced not only in parliament but also by the national associations of insurers, providers, employers and other stakeholders. The unions embraced the idea of a single scheme but rejected the introduction of competition. It soon became evident that the reform lacked political momentum and political support for it rapidly crumbled (Reference OkmaOkma, 1997). The Plan was declared politically dead in 1993 when the government did not receive parliamentary approval for some steps essential to the reform.

With hindsight, the political failure of market reform in the early 1990s can be seen as the result of two closely connected factors. First, there were many unresolved substantive policy questions. Would competition work? How would it affect access to health care and the distribution of health financing? Would it be technically possible to design a system of risk equalization that would adequately compensate insurers for differences in the risk profiles of their members? Was the implementation schedule realistic? Second, and on a deeper level, ideological convictions and political motives played an important role. The national associations of employers, unions, insurers, providers and other stakeholders denounced the Simons Plan as conflicting with the interests of their constituencies. For private insurers, acceptance of the Simons Plan would even mean the end of their business. A parliamentary evaluation of the failure of political decision-making concluded that the government had been unable to break through the so-called clay layer of interests. Another conclusion was that there had never been a sense of urgency (Willems Reference CommissionCommission, 1994).

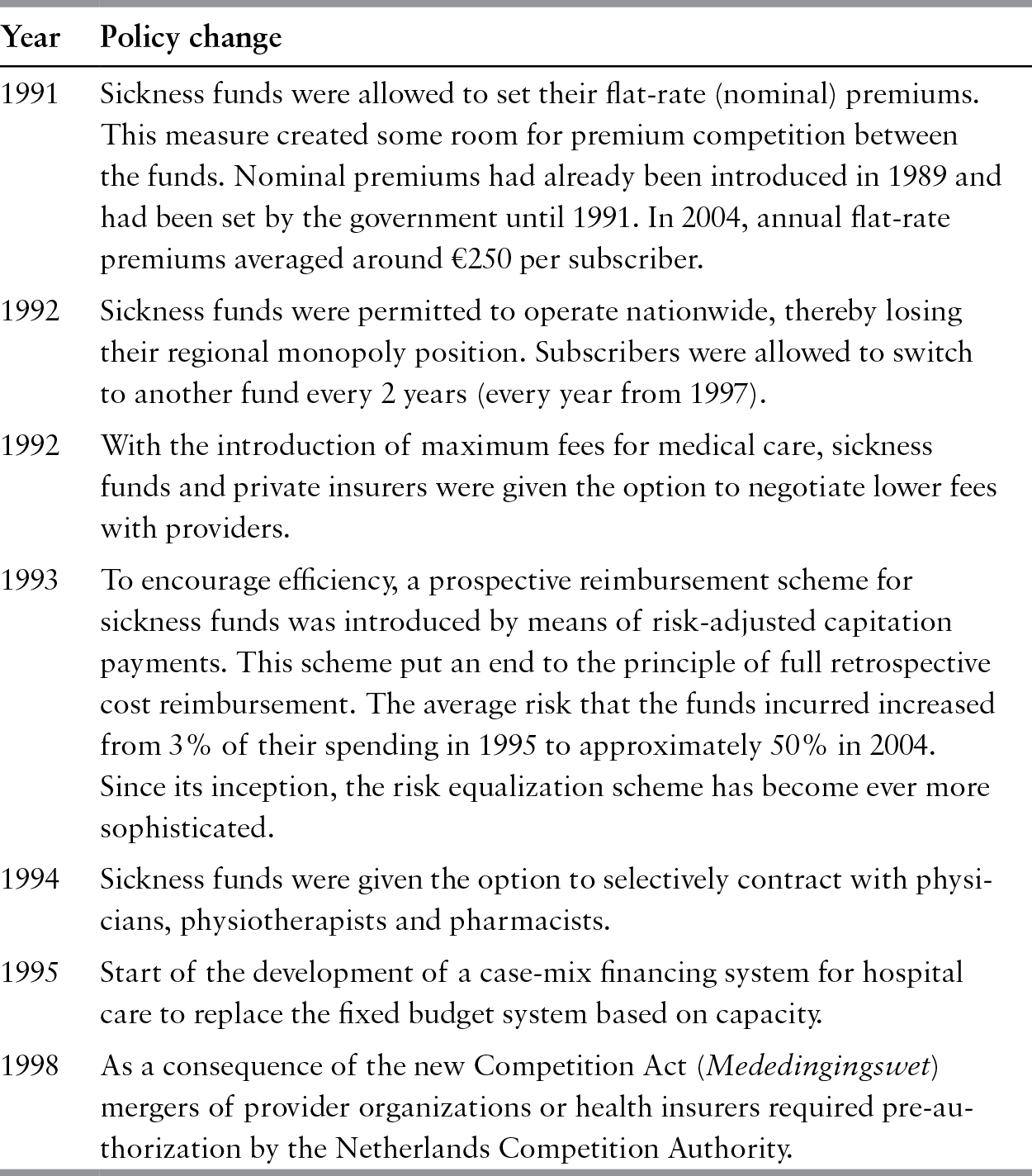

The new government (in place since 1994) declared that it would abstain from fundamental reform. Instead, it opted to move forward by means of incremental changes (see Table 11.2). Although the practical implications of these policy changes should not be overstated, each of them can be seen as a small but important step towards the 2006 reform, illustrating the evolutionary nature of the reform (Reference HeldermanHelderman et al., 2005; Reference Van der GrintenVan der Grinten, 2007).

Table 11.2 Overview of policy changes in the 1990s introducing some competition in statutory health insurance in the Netherlands

| Year | Policy change |

|---|---|

| 1991 | Sickness funds were allowed to set their flat-rate (nominal) premiums. This measure created some room for premium competition between the funds. Nominal premiums had already been introduced in 1989 and had been set by the government until 1991. In 2004, annual flat-rate premiums averaged around €250 per subscriber. |

| 1992 | Sickness funds were permitted to operate nationwide, thereby losing their regional monopoly position. Subscribers were allowed to switch to another fund every 2 years (every year from 1997). |

| 1992 | With the introduction of maximum fees for medical care, sickness funds and private insurers were given the option to negotiate lower fees with providers. |

| 1993 | To encourage efficiency, a prospective reimbursement scheme for sickness funds was introduced by means of risk-adjusted capitation payments. This scheme put an end to the principle of full retrospective cost reimbursement. The average risk that the funds incurred increased from 3% of their spending in 1995 to approximately 50% in 2004. Since its inception, the risk equalization scheme has become ever more sophisticated. |

| 1994 | Sickness funds were given the option to selectively contract with physicians, physiotherapists and pharmacists. |

| 1995 | Start of the development of a case-mix financing system for hospital care to replace the fixed budget system based on capacity. |

| 1998 | As a consequence of the new Competition Act (Mededingingswet) mergers of provider organizations or health insurers required pre-authorization by the Netherlands Competition Authority. |

Introduction of the 2006 reform

With the publication of its policy document A Question of Demand (Vraag aan Bod) in 2000, the government resumed the reform process. Its analysis was largely similar to that of the Dekker Report. It identified the strong supply orientation in health care as the key cause of inefficiencies, the absence of entrepreneurship and insufficient focus on consumer demand and health care quality. The dual structure of statutory and private arrangements was viewed as a source of inequity in financing health care and inefficiency. Like the Dekker Committee 14 years earlier, the government argued for the introduction of regulated competition. In 2004, after a few more years of debate, a new government (in place since 2003) sent its proposal for health insurance reform to the Dutch Parliament.

In this proposal the government opted for what may be termed a private model. The new health insurance scheme was construed under private law (an idea also supported by most sickness funds), to be operated by private insurers, to underscore the new roles and responsibilities of the state and the private sector in the post-reform health system. Following the new governance philosophy, health care had to be “given back” to the private sector after years of increasing state interference. Acknowledging serious market failures in health care and health insurance, the role of the state would be to create optimal conditions for competition and define public constraints to competition or public interests to preserve solidarity, universal access and affordability. A private scheme with public constraints could resolve the conflict between competition and public interests in health care. A private model was seen as the best way to stimulate entrepreneurial behaviour in health care and health insurers were therefore to be permitted to operate on a for-profit basis, although with a 10-year moratorium on the distribution of any profits. It also defined the market role of consumers in health care: the relationship between insurers and subscribers was to be based on an annual contractual arrangement that the subscribers could choose to renew or terminate. With this strategic choice, the government took a different route from Dekker and the 2000 report. The latter had opted for a universal scheme under public law with a leading role for the state to reflect the tradition and social nature of health insurance in the Netherlands.

Opting for a private model not only reflected a neoliberal trend in Dutch public policy-making at the time, it was also necessary in order to overcome opposition from private insurers, many of whom were negative about the reform. Whereas many sickness funds were sceptical about competition, private insurers feared that a single scheme would deprive them of their business and lead to a further increase in regulation. The private model was therefore a political instrument to temper their concerns. It was also a heavily contested choice and an important reason for the Labour Party to vote against the new legislation, even though it supported the idea of a universal scheme.

Health insurance post 2006

The 2006 Health Insurance Act (Zorgverzekeringswet) put an end to the traditional distinction between sickness funds and private insurers, introducing a single scheme covering all legal residents. The scheme is known as the basic health insurance scheme to be distinguished from the many complementary insurance schemes covering extra services not included in the benefits package of the basic scheme. The basic scheme was seen as significantly improving solidarity in health insurance. Implemented by private insurers, including former sickness funds, the new health insurance legislation created an institutional setting intended to encourage competition between insurers which, in turn, was expected to increase efficiency, to make health care more demand-driven and to improve its quality. It was also an attempt to upgrade the insurers’ role in health care. They were positioned as a countervailing power to providers. Their new role was to negotiate on behalf of their customers with providers on the costs, volume and quality of care within an institutional structure set by the state.

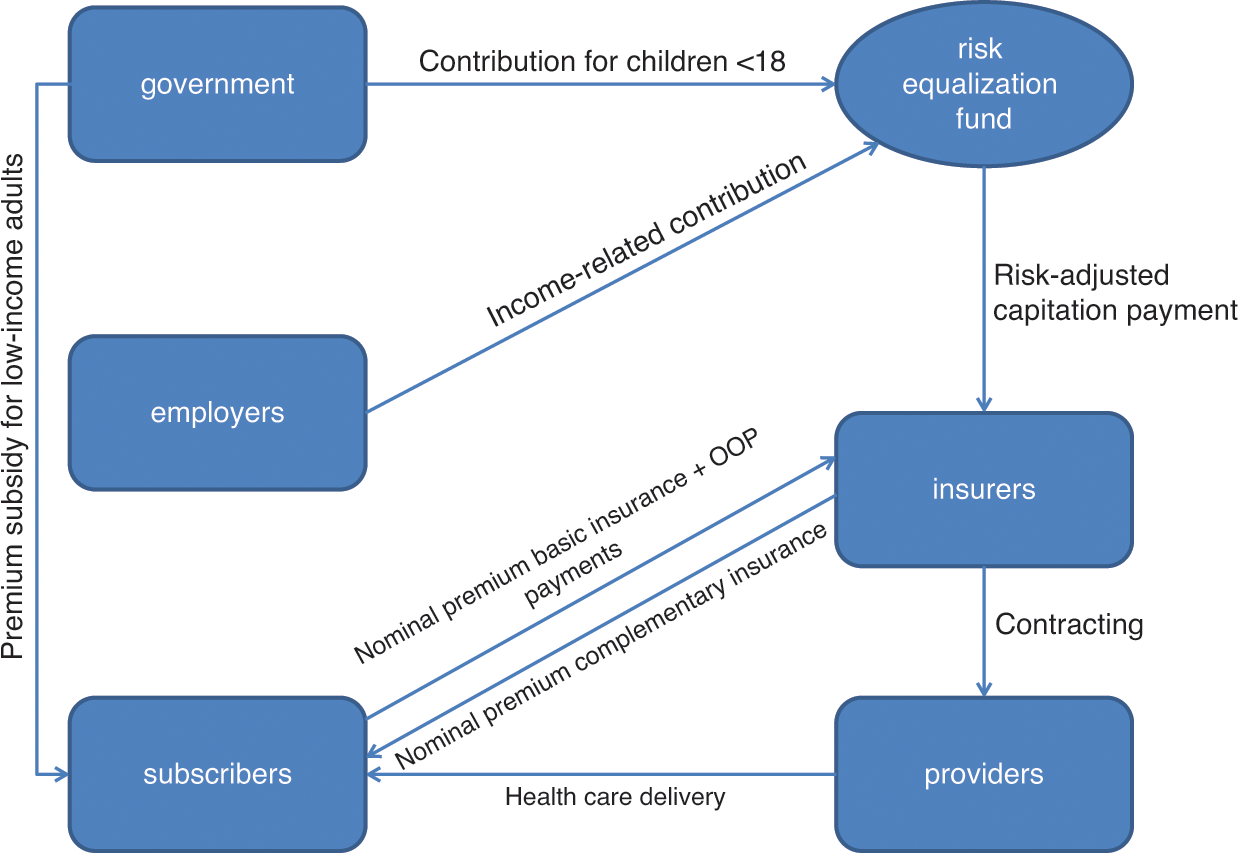

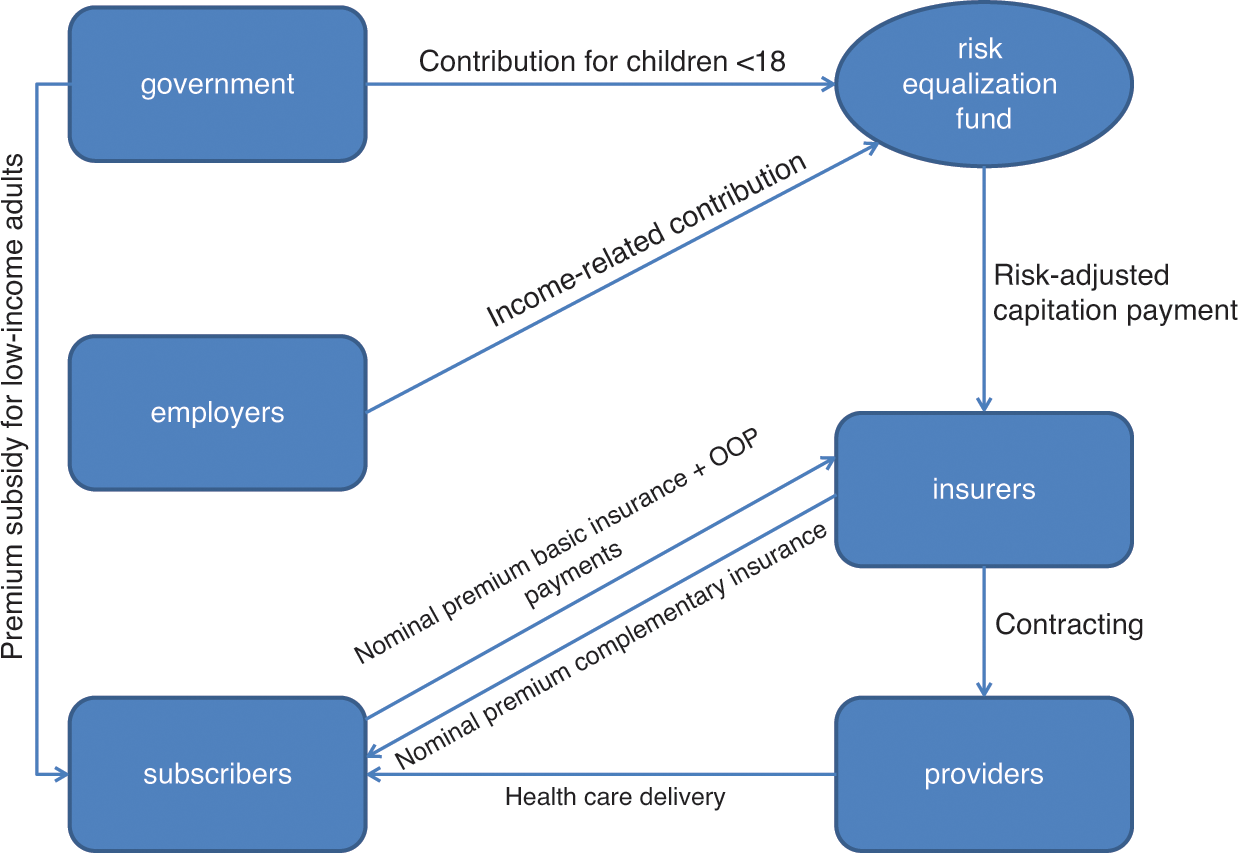

To stimulate consumer choice and competition the new legislation gives residents the right to terminate their contract at the end of the year and switch to another insurer or type of health plan. However, consumer choice is not unrestricted. Every resident is obliged to purchase a basic health plan (to be distinguished from complementary plans). Any person who fails to do so is uninsured. Insurers must offer open enrolment and cannot terminate contracts (ban on risk selection). A standard benefits package, similar to the benefits previously covered by sickness funds, is determined by government to prevent consumers from under-insuring themselves, to facilitate competition by enabling value-for-money comparison across insurers and to prevent risk selection through product differentiation. All adults pay an income-related contribution set by the government (see Fig. 11.1). These contributions flow into a central risk equalization fund, which compensates insurers for differences in the risk profile of their subscribers by means of a sophisticated risk-adjustment formula. The government pays contributions for children aged under 18 (Reference Van de Ven and SchutVan de Ven & Schut, 2008).

To foster competition, subscribers pay a flat-rate premium (known as a nominal premium) directly to their insurer. Each insurer is allowed to set its own nominal premium, which may vary depending on the nature of benefits selected by subscribers (for example, benefits in kind versus reimbursement, lower premiums for preferred-provider networks or higher voluntary deductibles), but cannot vary according to age, sex or pre-existing medical conditions.

Figure 11.1 Health insurance in the Netherlands after the 2006 reform

The Health Care Allowance Act (Wet op de Zorgtoeslag) compensates subscribers with low incomes for the cost of their nominal premium by means of an income-related cash subsidy (health care allowance). Competition is also stimulated by allowing insurers to negotiate with providers on health care prices, care volumes, service levels and also quality of care. To reinforce their negotiating power, the new legislation permits selective contracting of preferred providers. At the same time, insurers are obliged to guarantee their subscribers access to all types of care covered by the basic health plan (Reference Van de Ven and SchutVan de Ven & Schut, 2008)

To make people more aware of the costs of health care and motivate them to abstain from unnecessary care, the reform introduced a no-claims arrangement under which each subscriber had to pay a government-set annual charge of €255 on top of the nominal premium. Subscribers who incurred no health care costs in a given year received a refund of this premium (those who spent less than €255 received the difference). Because the refund did not prove to be cost-effective (Reference GoudriaanGoudriaan et al., 2006), it was replaced in 2008 with a mandatory annual deductible of €150. Children under 18, maternity care and general practitioner consultations are exempt from the mandatory deductible. Since then the mandatory deductible has been elevated every year to €395 in 2016 with a jump from €220 to €350 in 2013. The deductible has always been controversial in Dutch health care politics, particularly after some compensation programmes (health care allowances) ended in 2014 (see for example Section 3.3.1 in Reference KronemanKroneman et al., 2016). Municipalities have been made responsible for tailor-made compensation for which they receive a limited grant from the government. The Health Insurance Act also permits insurers to offer their subscribers a lower deductible under certain conditions. Opponents frame the mandatory deductible as a so-called penalty for disease and claim that it causes people to forgo care. There is some evidence for this adverse effect but evidence of its magnitude is missing (Reference Van EschVan Esch et al. 2015).

The new scheme builds upon the traditional division between basic and complementary health insurance. Although the purchase of the basic plan is mandatory, taking out a complementary plan is voluntary. In fact, one may consider complementary health insurance as pure private health insurers: insurers are free to set their own policy conditions and benefits.

In 2015, revenues from nominal premiums accounted for 36.6% of total health insurance revenues (excluding complementary private health insurance cover), revenues from income-related contributions for 50%, state grant for children for 5.9% and out-of-pocket payments for 7.5% (Ministry of Health, 2016).

The many regulations, mainly aimed at protecting the general good, make the new scheme different from pure private schemes, which usually feature a high degree of voluntary action, differentiated products, risk-related premiums and medical underwriting. In fact, debate about whether or not the new scheme is seen as public or private is to some extent semantic and depends on the perspective taken. The fact that the new scheme is mandatory and includes many legal provisions to protect the general good may be used to argue that it is a public rather than private scheme. This is also reflected in health care statistics: between 2004 and 2006 the share of public financing in current expenditure on health jumped from 65.6% to 85.7% (OECD, 2016). However, from the subscriber and insurer perspectives (annual contracts; private insurers, some commercial) it is clearly a private scheme.

The mixed public–private nature of the new scheme raised a debate about the compatibility of the new scheme, presented as a private scheme, with the third non-life Insurance Directive of the European Economic Community. The Directive permits governments to set rules to protect the general good, but these rules must be necessary and proportional. Communication with the European Commission on this issue established that the regulations were indeed necessary and proportional.

Effects of the 2006 reform

Effects on consumer behaviour

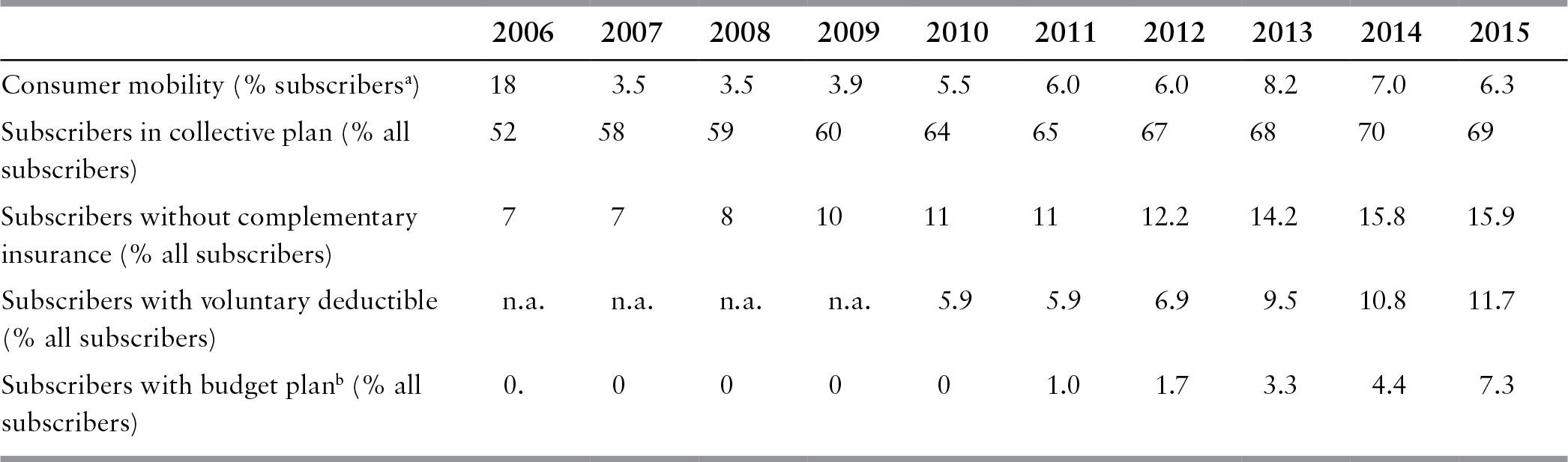

Table 11.3 summarizes some trends in consumer behaviour after the enactment of the Health Insurance Act.

Table 11.3 Trends in consumer behaviour in the Netherlands, 2006–2015

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consumer mobility (% subscribersa) | 18 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 8.2 | 7.0 | 6.3 |

| Subscribers in collective plan (% all subscribers) | 52 | 58 | 59 | 60 | 64 | 65 | 67 | 68 | 70 | 69 |

| Subscribers without complementary insurance (% all subscribers) | 7 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 12.2 | 14.2 | 15.8 | 15.9 |

| Subscribers with voluntary deductible (% all subscribers) | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.9 | 9.5 | 10.8 | 11.7 |

| Subscribers with budget planb (% all subscribers) | 0. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 3.3 | 4.4 | 7.3 |

Notes: n.a.: not available.

a Subscribers switching to another insurer in a given year.

b Budget plans are lower-priced plans with preselected providers for planned care.

After an unexpected 18% of subscribers switched in 2006, consumer mobility dropped significantly. In 2010–2015 it was hovering at around 6–7%, still suggesting a competitive health insurance market. Only 1.5% of consumers switched four times or more to another insurer in 2006–2016; 73% had never switched (Vektis, 2016). Consumer mobility was highest among younger, more educated people, people who perceived their health to be good, people living in large cities and adults with a partner and one or more children. The most important reason for switching was to benefit from a lower premium.

The new scheme allows employers or other groups (for example, members of a sports club, patient associations) to negotiate a collective contract in return for a discounted nominal premium. Legislation limits the maximum premium discount to 10%. Before the 2006 reform, employer-based contracts were common in private health insurance. After the reform, the market for collective contracts became very competitive because insurers sought opportunities for expansion in this market segment. Currently, collective contracts account for more than two thirds of the market. More than two thirds of collective contracts are employer-based. Collective contracts have always been controversial, because they undermine solidarity (see below). There are also questions about their added value for employers and subscribers.

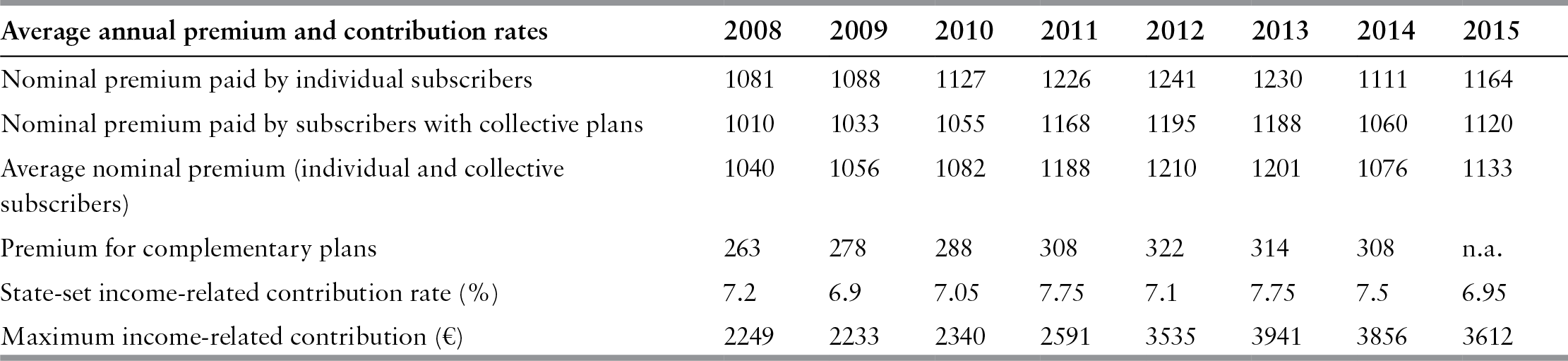

Complementary plans have long been popular in Dutch health care. However, Table 11.3 shows a steady decline of the percentage of subscribers with such a plan. The drop is probably due to the substantial increase in the premiums of complementary plans as well as some declines in benefit levels (see Table 11.4); decreases in premiums observed since 2012 do not seem to have affected this negative trend.

Table 11.4 The development of nominal premium and income-related contribution rates in the Netherlands, 2008–2015

| Average annual premium and contribution rates | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal premium paid by individual subscribers | 1081 | 1088 | 1127 | 1226 | 1241 | 1230 | 1111 | 1164 |

| Nominal premium paid by subscribers with collective plans | 1010 | 1033 | 1055 | 1168 | 1195 | 1188 | 1060 | 1120 |

| Average nominal premium (individual and collective subscribers) | 1040 | 1056 | 1082 | 1188 | 1210 | 1201 | 1076 | 1133 |

| Premium for complementary plans | 263 | 278 | 288 | 308 | 322 | 314 | 308 | n.a. |

| State-set income-related contribution rate (%) | 7.2 | 6.9 | 7.05 | 7.75 | 7.1 | 7.75 | 7.5 | 6.95 |

| Maximum income-related contribution (€) | 2249 | 2233 | 2340 | 2591 | 3535 | 3941 | 3856 | 3612 |

The low percentage of subscribers with a voluntary deductible on top of the mandatory deductible suggests a widespread attitude of risk aversion in health insurance. Nevertheless, the percentage of subscribers with a voluntary deductible doubled to 12% between 2010 and 2015. Of these subscribers 71% opted for a maximum voluntary deductible of €500 (Vektis, 2016).

Freedom of choice

The 2006 reform was, among others, intended to give consumers more choice. Under the new legislation they can switch to another insurer by the end of the year and to another type of health insurance plan. There is a choice between benefit-in-kind plans, cost-reimbursement plans and a combination of both. Insurers also offer lower-priced plans with preselected providers for planned care (budget plans), lower reimbursement percentages for noncontracted care and on-line communication between insurer and subscriber. The number of these budget plans grew from 5 in 2011 to 17 in 2015. The total number of insurance plans was 71 in 2015 (NZa, 2016). Opponents of competition in health insurance often criticize this number. In their view it is a source of waste and many customers are not able to compare plans and make an informed choice.

Customers may also be deceived by the complexity of insurance plans. For instance, it may be unclear to them which providers have been contracted by their insurer, although insurers are requested to list the contracted providers on their websites.

Premium and contributions

Table 11.4 shows the development of the average nominal premium rate for individual subscribers and subscribers with a collective insurance plan since 2008. The percentages demonstrate that individual subscribers pay a higher nominal premium than subscribers with a collective plan do. As the cost to premium ratios of individual and group plans do not differ much it seems evident that subscribers with an individual plan pay for the premium discounts in collective plans.

Between 2008 and 2012 the average nominal premium rose by 16.3%. The remarkable drop in 2014 is attributable to the insurers’ decision to use their financial reserves to lower premiums. Insurers claim that they did so voluntarily, but political pressure also played a role (in its calculation of the expected premium, the government assumed that insurance companies would transfer €500 million from their reserves to lower subscriber premiums; Reference Maarse, Jeurissen and RuwaardMaarse, Jeurissen & Ruwaard, 2016). The lower premium was a one-off event; further increases are expected in the future. However, the average premium in 2015 was still less than the average premium in 2011. There is a large variation in premium rates. For example, in 2014, the difference between the highest-priced and lowest-priced nominal premiums was 30% (Vektis, 2016). The maximum income-related contribution has risen by 60.6% since 2008, but this is less visible because it is part of income tax.

Non-insured and defaulters

Under the Health Insurance Act each person aged 18 years and older is requested to purchase a basic health insurance plan. A person who fails to do so is uninsured. The number of people without insurance is estimated at 0.1% (NZa, 2016). This low percentage is attributable to a joint campaign conducted by the government, municipalities and insurers to track uninsured people. A more serious problem is the number of defaulters, defined as people who failed to pay their insurance premium over an uninterrupted period of 6 months. The latest estimate of the number of defaulters showed a decline from 325 000 in 2014 to 280 000 in 2015 (2.1% of insured people aged 18 or older) (Ministry of Health, 2016). This reduction is attributable to a new legislation which enables insurers to make tailor-made arrangements with defaulters on repayment schedule.

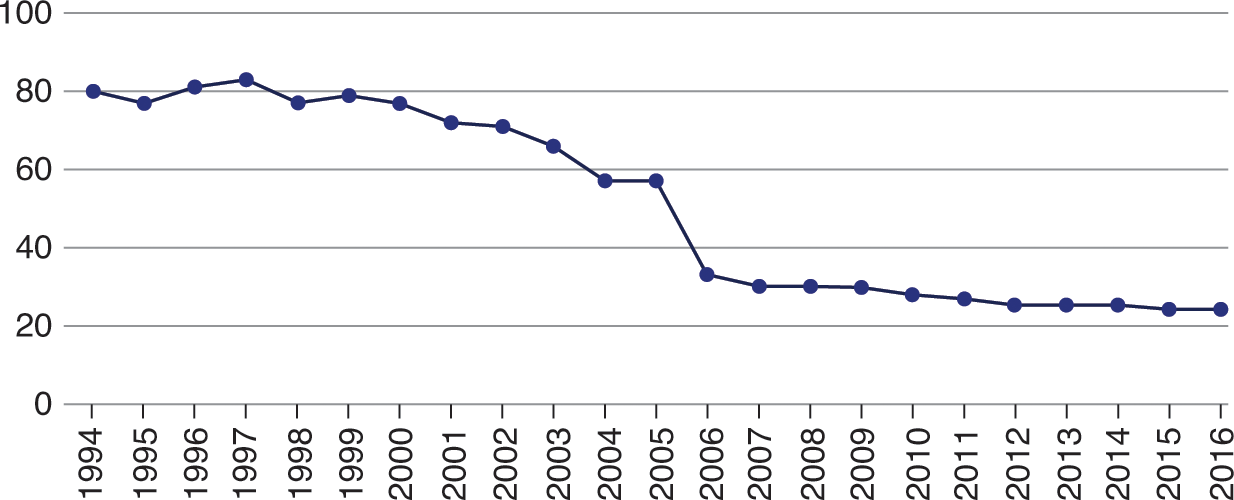

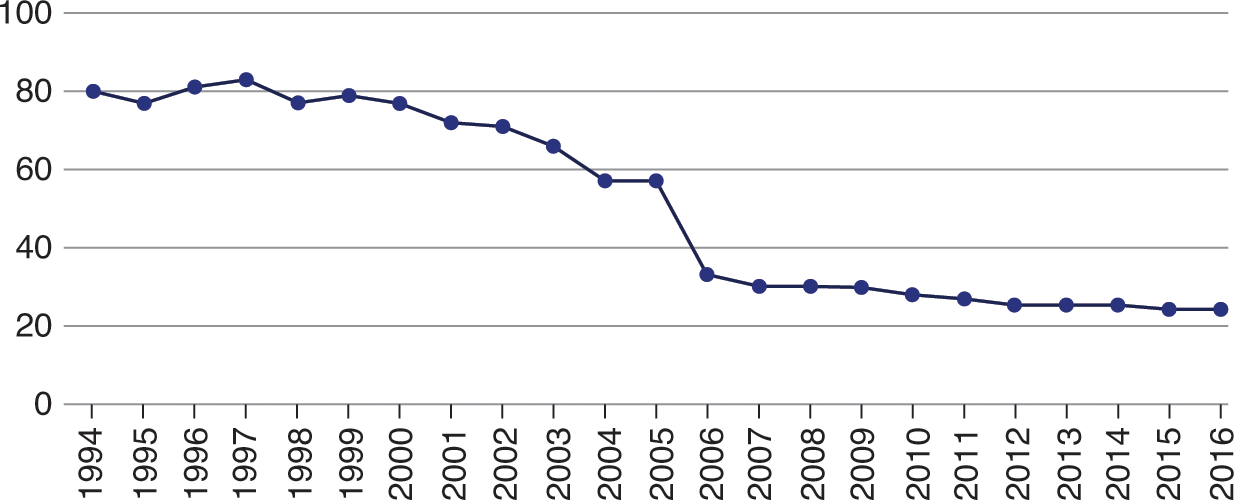

Effects on the insurer market

The number of insurers had already seen a steady decline in the pre-reform period (see Fig. 11.2). Consolidation was driven by the need to reduce administrative costs and enhance risk pooling. In 2006 the total number of insurers fell by a further 42% (from 75 to 53) due to mergers between sickness funds and private insurers. In 2015, there were 25 health insurers, grouped into nine business companies. The four largest companies each had a market share of between 13% and 32%; together the so-called big four covered about 90% of the market. In 2006–2016 no new insurance company managed to enter the market; one company tried to do so but failed. The oligopolistic and, in some regions, even semi-monopolistic, structure of the health insurance market has given rise to concerns because of the danger of cartel formation and the erosion of consumer choice. It also explains why providers, in particular providers working in private practices, complain about the strong power position of health insurers. They perceive the insurers’ contract as a dictate. Insurers on their side argue that their power position is grossly overstated, particularly in relation to hospitals (Reference Maarse, Jeurissen and RuwaardMaarse, Jeurissen & Ruwaard, 2016). The latter conclusion was recently also drawn in a report on the newly established power balance in Dutch health care. There is a great deal of mutual dependence between insurers and providers: insurers feel compelled to contract almost all providers, especially hospitals and primary care offices (Reference Loozen, Varkevisser and SchutLoozen, Varkevisser & Schut, 2016).

Another aspect of the insurer market is administrative costs. In 2005 these costs were 4.2% for sickness funds and 10.7% for private insurers. Total administrative costs decreased to 3.0% in 2015. Hence, the reform has resulted in lower administrative costs. Administrative costs also include the costs of marketing (and commissioning) which critics of competition see as waste of public money. Administrative costs of complementary health insurance plans are significantly higher (12.4%) (Vektis, 2016).

The financial position of insurers is sound. After incurring deficits in the 2006–2008 period, insurers have achieved surpluses since 2009. For instance, in 2013 their legally required solvency rate was more than twice the officially required rate of 11% (Vektis, 2016). These results have prompted a political discussion on the insurers’ surplus, mostly framed as high profits.

Contracting

The cornerstone of the 2006 reform was to transform health insurers from relatively passive bureaucratic reimbursement agencies into active health care purchasers who negotiate with providers to obtain high-quality health care at low cost for their subscribers. Under the new legislation they are no longer obliged to contract with each provider. For a long period of time negotiations on prices, volume and quality were barely possible. Insurers simply had no reliable information on costs and quality of care. The market structure in some regions and fear of reputation damage were also not conducive to insurers engaging in hard negotiations. Furthermore, there was a temporary safety-net in place, which compensated insurers for a deficit.

This situation has changed. More information is now available on quality and prices. Whether quality is really an important topic in the negotiations is disputed. Insurers say that they focus on quality, but, according to anecdotal evidence, providers often claim that quality of care is not the key subject in negotiations. Nevertheless, hospitals are no longer automatically contracted for all types of care. In 2010, a large insurer announced that it would no longer contract four hospitals for breast cancer surgery, because the quality of their breast cancer care, measured in terms of capacity, volume (number of operations) and patient satisfaction, did not meet minimum standards. This initiative has been followed by other insurers, mostly for some forms of elective surgery. Some insurers have also set up insurance plans with pre-selected providers. Most contracting currently comes down to negotiating an annual-budget and a predetermined volume level. In 2015, for the first time since the 2006 reform, a contract between a health insurer and a hospital explicitly concerned improved quality. The cardiology department of the Catherina Hospital and insurer CZ have developed a method to measure quality. If quality improves, the hospital receives an extra amount of money. Another new development is for insurers to agree on multi-year hospital budgets. This gives the hospitals more leeway in the use of their resources, especially when patient volumes decline. One large insurer (VGZ) had 10 such agreements in 2017 (www.nu.nl).

To influence patient decisions about choice of provider, insurers have so far mainly used soft instruments, such as providing them with information on waiting times for different hospitals. Some insurers use positive incentives, such as waiving the mandatory deductible if patients visit a preferred hospital; others require patients to visit preferred providers for non-emergency care. However, the use of such incentives by insurers and patients is still marginal.

Impact on solidarity

As discussed before, one of the objectives of the reform was to strengthen solidarity by putting an end to the traditional dual structure of health insurance and introducing a single and mandatory scheme for all legal residents in the Netherlands. What is the impact of the reform on solidarity?

Let us first look at income solidarity by analysing income-related contributions. Two points are important here. First, it should be mentioned that there is a cap on the income-related contribution. As a result, people with low incomes pay proportionally more than people whose income is higher than the maximum threshold set by the state. The second point relates to the nominal premium subsidy for people with low incomes. In 2013, 62% of households qualified for a subsidy. The government’s policy has been to rein in spending, not only by reducing the number of people qualifying for a subsidy but also by reducing the level of compensation (people with the lowest incomes were exempted from this measure). A rough analysis by Reference Vermeend and van BoxtelVermeend & van Boxtel (2010) concluded that health care financing was still regressive after the reform, even when taking into account the state-paid compensation.

To guarantee risk solidarity, the Health Insurance Act obliges insurers to accept each applicant (open enrolment). Furthermore, insurers are forbidden to differentiate their premiums according to medical risk; instead, they must apply a community rating (ban on premium differentiation). Offering differentiated benefits packages to their customers is also restricted because the basic benefit package is set by the Minister of Health. Furthermore, a sophisticated risk equalization scheme is in place to compensate insurers for differences in risk profile. According to the theory of regulated competition, variation in nominal premium rates should predominantly reflect differences in efficiency (Reference Van de VenVan de Ven et al., 2013).

Despite the formal ban, risk selection cannot be ruled out (Reference DuijmelinckDuijmelinck et al., 2013). The main cause for this is that the risk equalization scheme is imperfect (if it is ever possible to construct a perfect scheme). The following example serves as an illustration. If one singles out the group of subscribers with the worst score on health, insurers would make a predictable loss of €2275 if risk compensation was absent. Risk-adjusted payments from the equalization fund reduce this loss, whereby sophisticated models with several parameters reduce it by more than simple models. However, even with the most sophisticated model the predictable loss for this group of subscribers is still estimated at €646 a year (Reference Van Kleef, Van Vliet and van de VenVan Kleef, Van Vliet & van de Ven, 2012). The loss makes it attractive for insurers to look for loopholes in the legislation to circumvent the ban on risk selection. There are several strategies for this, including targeting young people with higher incomes (although this is officially forbidden) or offering a significant discount in exchange for a voluntary deductible. Indeed, people with more favourable risk profiles switch more between plans and more often choose a voluntary deductible (NZa, 2016).

Impact on health care spending

One of the objectives of the reform was to foster competition and, in that way, curb annual growth in health spending. Is there evidence for this effect? To answer this question, it should first be emphasized that the introduction of the reform was an expensive affair, with the implementation of the scheme to compensate people with low incomes for the nominal premium costing around €2.5 billion. One can argue that the reform would not have been feasible in times of austerity (between 2004 and 2006 the national economy flourished). Also note in this respect that the reform, contrary to the reform of long-term care in 2015, did not at the time explicitly seek any significant expenditure cuts (Reference Maarse and JeurissenMaarse & Jeurissen, 2016).

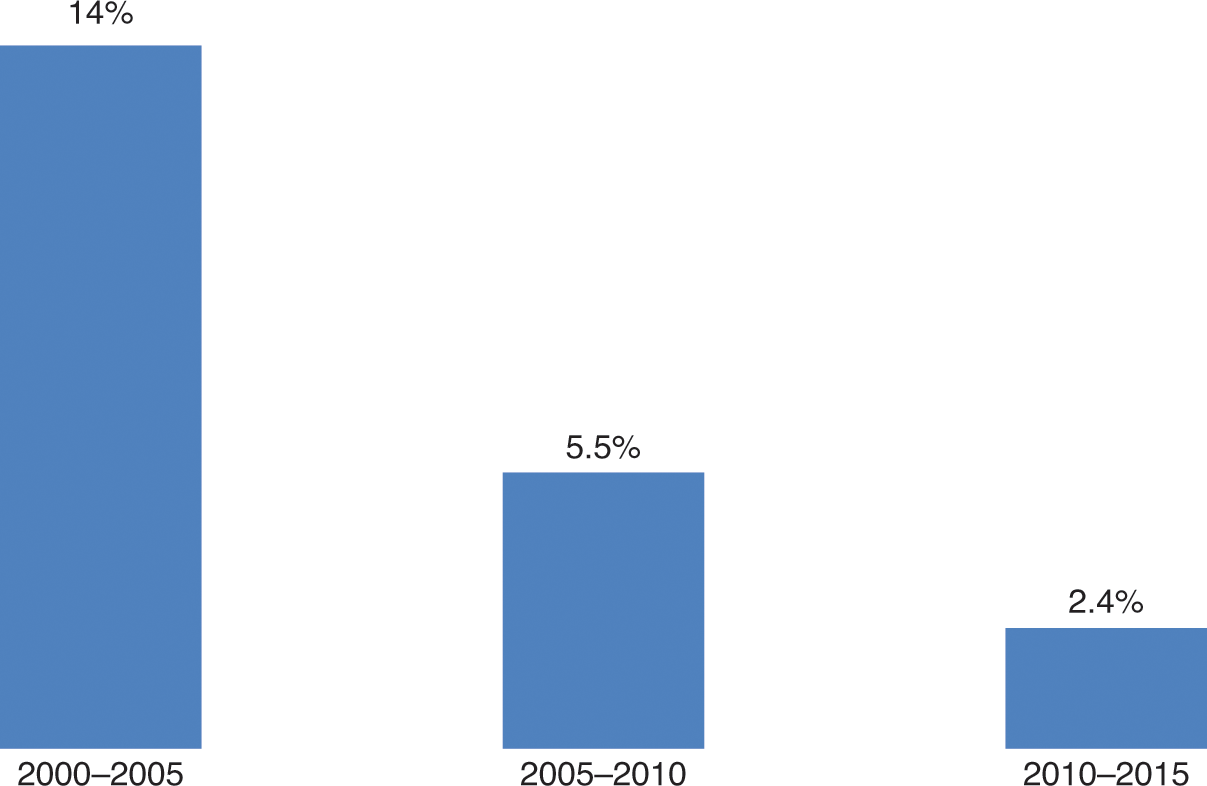

Fig. 11.3 presents the average annual percentage growth of health care expenditure in three consecutive periods. The percentages clearly exhibit a declining trend. The high percentage in 2000–2005 is largely attributable to the government’s policy of removing waiting lists. The lower percentages in 2005–2010 and particularly 2010–2015 are often used in the political debate to argue that the new system is effective in curtailing health care expenditure growth (since 2012, health care spending has been lower than the maximum growth rate set by the government). However, there is limited evidence for this claim. Although price negotiations may have had some effect, it seems more plausible that the low growth rate in 2010–2015 was largely the result of an agreement in 2012 between the government and the national associations of hospitals and insurers to cap the annual growth of hospital expenditure to 2.5% in the 2012–2015 period. In a renewed agreement in 2013 the percentage was further reduced to 1% in the 2015–2017 period. The agreement nicely fits in the tradition of shared responsibility of the government and the national associations in health care policy-making (and many other policy sectors) (Reference Maarse, Jeurissen and RuwaardMaarse, Jeurissen & Ruwaard, 2016). However, it seems antithetical to competition to set maximum growth rates. The agreement also demonstrates that the scope for market competition in the Netherlands should not be overstated.

Figure 11.3 Average growth rates in health care expenditure in the Netherlands, 2000–2015

One area where competition seems to work is the market of outpatient generic drugs. Health insurers have managed to negotiate significant price cuts, as a result of which total spending on prescription medicines has been flat in nominal terms over the last decade (www.farminform.nl).

Trust

As explained before, the reform has always been controversial. An important aspect of this controversy is trust (or lack of trust) in health insurers. According to a recent survey, 57% of respondents said that they were satisfied with their insurer. However, when asked about the role of insurers in general, one can observe a serious lack of trust: only 31% of the respondents said they trusted health insurers. For GPs and hospitals these figures were, respectively, 87% and 73%. Insurers often tend to be seen as money-driven organizations making ‘too high profits’ (Reference 375Brabers, Reitsma-van Rooijen and De JongBrabers, Reitsma-van Rooijen & De Jong, 2014). One may speak of a problem of trust: patients seem to trust their doctor, but not so much their insurance company (Reference Boonen and SchutBoonen & Schut, 2011). Over time this may undermine efforts to increase efficiency through the use of selective purchasing (see also Discussion).

The low level of trust motivated insurers to start a campaign in the media in 2015 to explain what they were doing and how they defined their role in the new system. The effect of this campaign on public opinion is unclear.

Discussion and conclusions

Private health insurance has always been a constituent element of health insurance in the Netherlands. The traditional distinction between the sickness funds and private insurers that developed in the pre-war period was legally institutionalized in the Sickness Fund Decree of 1941 and later by the Sickness Funds Act of 1964, which introduced compulsory insurance for a section of the Dutch population (employees earning below a threshold). Those not entitled to join sickness funds had to rely (voluntarily) on private health insurance to be protected against the costs of ill health. As a result, about 35% of the population had private cover, although this figure is misleading because it includes people covered by arrangements for specific categories of public servants and people covered by the WTZ. The share of the population with pure private health insurance was estimated at 24% in 2005.

The 2006 reform had major implications for private health insurance. Substitutive cover was integrated with the sickness fund scheme to form a single, mandatory scheme covering the whole population. This should be understood as a major achievement, putting an end to decades of political discussions. The new scheme is operated by private insurers, many of them former sickness funds. From a legal perspective, the new scheme is private. However, the legislation contains many provisions – termed public constraints – to preserve the general good. As a result, it may be concluded that the new scheme is an attempt to combine private structure and social purpose – an arrangement that could be called a private social health insurance scheme. The scheme’s hybrid status is important from the perspective of European Union competition and single market rules.

The health insurance reform triggered a change that can be best described as gradual transformation. On the one hand it implied a significant alteration of the health insurance landscape with the introduction of a single mandatory scheme operated by private insurers under private law as the most significant institutional changes. At the same time, many elements of the former sickness fund scheme were continued. The Health Insurance Act includes numerous public constraints to preserve the legacy of the past and avoid the adverse consequences of an unregulated private health insurance market for solidarity and universal access.

From the very beginning the reform has been controversial. It took, for instance, almost 20 years between the publication of the report Willingness to Change (1987), which recommended a reform based upon the principles of regulated competition, and the year the Health Insurance Act came into force (2006). This long period indicates that the need for and direction of reform were not self-evident. Controversy has not weakened since 2006. This is perhaps best illustrated by an event in 2013 when the government’s legislative proposal to stimulate selective contracting by relieving insurers from an unofficial obligation to reimburse 75–80% of the costs of noncontracted care was defeated in the Upper Chamber. The government’s proposal was rejected on the grounds that it would restrict free choice of physician.

Currently, health insurance is still the subject of a political struggle. There is much debate on the size of the mandatory deductible, which is seen as an unfair obstacle to accessing medical care. Left-wing political parties argue for a lowering or even full abolition of the deductible, which would require significantly higher premiums or income-related contributions. Another hot issue is the presumed power of insurers. The election programme of the Socialist Party included a proposal for a radical overhaul of the present health insurance landscape by introducing what is called a National Health Fund, the elimination of all insurers, the replacement of nominal premiums with only income-related contributions and the abolition of any mandatory deductible. The probability of acceptance of this plan seems low, not only because it would be very costly, but also because it would trigger a new ideological debate on the structure of health care. Many practical problems would remain unsolved for years. There is also little enthusiasm for the introduction of a National Health Fund among most other parties. The proposal signifies the contested structure of the current form of health insurance arrangements, but there is no good reason to believe that this will alter in the near future.