Chapter 2 Localizing Piers Plowman C: Meed, Corfe castle, and the London Riot of 1384

“Liminal, emotional, and indeed erotic”: few constituents of the medieval literary archive, certainly not authorial attribution, can hope to be described in the terms that David Wallace assigns to place, an entity to which are attached “heightened states of emotion: the pleasures of being fully in place; the pains and travails of being out of it.”1 While Langland is neither a celebrator of hearth and home nor a follower of Mandeville, he is particularly attuned to other of the pleasures and pains specific to place, especially as it determines the nature of the individual's quest for St. Truth. Take Wit's invective against the restlessness of the religious, in lines unique to A:

This inversion of the cliché that it is the rolling stone that gathers no moss reinforces the near-eroticism of place: here, it is the stationary marble that stays clean, an image that evokes in the reader a tactile, pleasurable sense that no reference to a monastery or guildhouse could easily have provided, even if it is what Wit had in mind.

Place's role in the production of Piers Plowman, too, has long determined, or at least reflected, its meaning in the eyes of its modern readers. The A version's content and form are somewhat tentative, rendering its extant manuscripts' localization to the hinterlands unsurprising and appropriate. B is the urbane and bold one: it belongs to London, where indeed that version's earliest and most important manuscripts were produced. And the great nineteenth-century editor Walter W. Skeat asserted as a “fact” the notion that “the poet grew more conservative in his ideas and more careful in his expressions as he grew older,” which well fit his proposal that Langland retired to his home region of Malvern to compose the final, C version.2 A modern articulation of this thesis appears in Steven Justice's influential identification of the “principled evasion” of C's politics in the wake of the Rising of 1381.3 The fact that the “best” C-version manuscripts, those of the so-called i-group, “form a dialectally cohesive South-West Midland group,” as M. L. Samuels concluded in an influential study, has supported this claim,4 while the more recent localization of those copies' production to London has led to the converse conclusion, “that Langland remained resident in London during this process, and that his holograph was released to the London book trade rather than to a number of local Worcestershire scribes.”5

To correlate certain of the extant manuscripts with the poet himself is to believe that the archive has already interpreted itself, as it were. Yet those copies of Piers Plowman embody no “evidence,” per se, for the location of the poet when he was writing. The only manuscripts that might have done so – the holographs – are gone, and even they might not have provided any clues. If the archival support for the localization of Piers Plowman C, upon which this chapter focuses, is absent, then we need to turn to the poem itself: likewise the product of assumptions that include the notion that Langland had retreated to Malvern in the wake of the Rising to write a clearer, perhaps duller, certainly safer poem. These assumptions, I will suggest, have prevented recognition of what otherwise would have appeared to be clear responses to the explosive events that rocked the London streets in February 1384. Thus, while one of my major goals is to argue positively for London as site of the production and earliest transmission of the C version, this chapter will also be advocating the more fundamental point that our methods of localization to date, including those that happen to result in a London localization for C, have been circumscribed by a commitment to other beliefs that in effect answer the question before it is asked. However much we want the archive to serve as an external guarantor of, or a check on, our response to the poem itself, subjective acts of literary interpretation must at the least accompany, perhaps trump, the supposedly sounder archival approach on which professional academic scholarship since the days of Skeat has rested its claims.

In London and upon London

One reason for the particular interest in the localization of C is that Reason, Conscience, and Will himself are heavily invested in the topic as well, the latter answering the former two interrogators, as most readers have it, with the assertion “And so y leve in London and opelond bothe,” “in London and the country too.”6 This phrase, perhaps more than any other in Piers Plowman, has served as a touchstone for modern scholarship of the poem in all its versions, of the poet, and even of the alliterative corpus at large. It both generates and is the culmination of Steven Justice's account of Langland's “principled evasion” of the urban evils associated with B to the conservatism of C and the West Midland countryside (see note 3); is central to Anne Middleton's argument that the apologia pro vita sua dramatizes an interrogation under the 1388 Statute of Laborers, and as such is at the core of all recent discussions of C's dating: “Will's reply thus appears to be an effort to defeat the statute's most fundamental premise: that everyone ultimately belongs to a single local habitation”;7 serves as the main title of Simon Horobin's study of the production of some C manuscripts; and provides the conceit of Christine Chism's claim that the alliterative romances at large “imaginatively claim dual citizenship of ‘London and opelond bothe’.”8

Yet the chances are that fewer than one in four medieval readers of C encountered it, if extant manuscripts are representative of that version's life: four of seventeen C witnesses, XYJU, read opelond, while the remaining thirteen, comprising the majority P-group manuscripts, attest: upon londoun KGN; on londen PRVAQS; in londone E; by londoun F; out of londone M; up þe londe D.9 As George Russell and George Kane say, “either of the main variants would pass muster if unchallenged.”10 Endorsing Skeat's interpretation of the P-group reading – “‘I live in London, and upon London,’ i.e. upon the work which London affords”11 – they propose as Langland's original up london, which could easily have generated the scribal alternative for the very reasons that it appeals to modern critics as well: “Assuming originality of upon or up london, uplond, ‘in the country,’ might suggest itself as in balance with preceding in london; or knowledge of the poet's actual circumstances; or the suggestion that he ‘moved about’ in 49–51 following might have prompted substitution.”12 Fortunately, users of editions, unlike editors of hard-copy volumes themselves, need not decide either way.

It is appropriate that a single contested phrase about the dreamer's location has determined so much thought about the whole poem's localization. This serves as a reminder of how reliant such large claims often are on relatively insecure beliefs about local issues, as it were. The set of assumptions that issues in opelond's centrality has its origins, as does so much in Langland studies, in the work of Skeat, who based his belief that Langland retreated to Malvern to engage in his final, “conservative” revision on three indications. The only one to retain its power is the South West Midlands dialects of the “best,” i-group manuscripts of the C tradition,13 forging a connection between any extant manuscripts and the author that over the past few years has only grown stronger, with such claims as that Huntington Hm 143, MS X, has “some direct connection to the author” proliferating.14 Such affiliations of certain surviving copies with the poet and his locale have moved from Skeat's impressionistic tone to an almost scientific one in the wake of the publication of the Linguistic Atlas of Later Medieval English in 1986, which signaled the arrival of dialectology as one of most powerful tools of Middle English studies.15 Using securely localizable texts as their anchors, practitioners are able to determine with a fair degree of certitude the region in which the text of a given manuscript's language was formed. That site is not necessarily where the text was copied, since both authors and scribes traveled.

So much is clear enough, and sophisticated tools enable critics to distinguish the various layers of dialects in texts far removed from their origins. The difficulty arises in determining the extent to which scribes left the marks of their own language on their texts, as opposed to faithfully reproducing the language of their exemplars even where that language is in an unfamiliar dialect. Samuels, assuming that scribes left heavy traces as a matter of course, believes it would be “very strange indeed if each C-MS (if written in London) had found a south-west Midland scribe”;16 while Horobin finds evidence of the contrary, and thus locates the i-group manuscripts to a circle of London scribes who were careful to transmit their copies' West Midlands dialect, a claim that has led advocates of Samuels's earlier, supposedly “well established” localization of C to Malvern to recant that position: the suggestion “is not well founded.”17

In such dialectal studies, some distinctions are constantly, and appropriately, identified and maintained: those between authorial and scribal dialects, and between the sites of linguistic formation and of the production of later manuscripts. But that level of care has not extended to two other, no less important sites, which are collapsed as a matter of course in this Malvern vs. London debate: the site of the work's original production and that of its later dissemination. The culprit is the concept of textual “superiority.” For both proposed sites of C's production, Malvern and London, are the result of the determination of the localization of “the ‘better’ i-group” as opposed to that of “the inferior p-group.”18 The logic, although never articulated as such, seems to be that “that the C-text copies, too” – that is, the “better” ones – “were almost certainly first released in London,” as Andrew Galloway has said, “their western dialect a sign of a shorter and perhaps more explicitly authorized London textual history than the A or B copies.”19

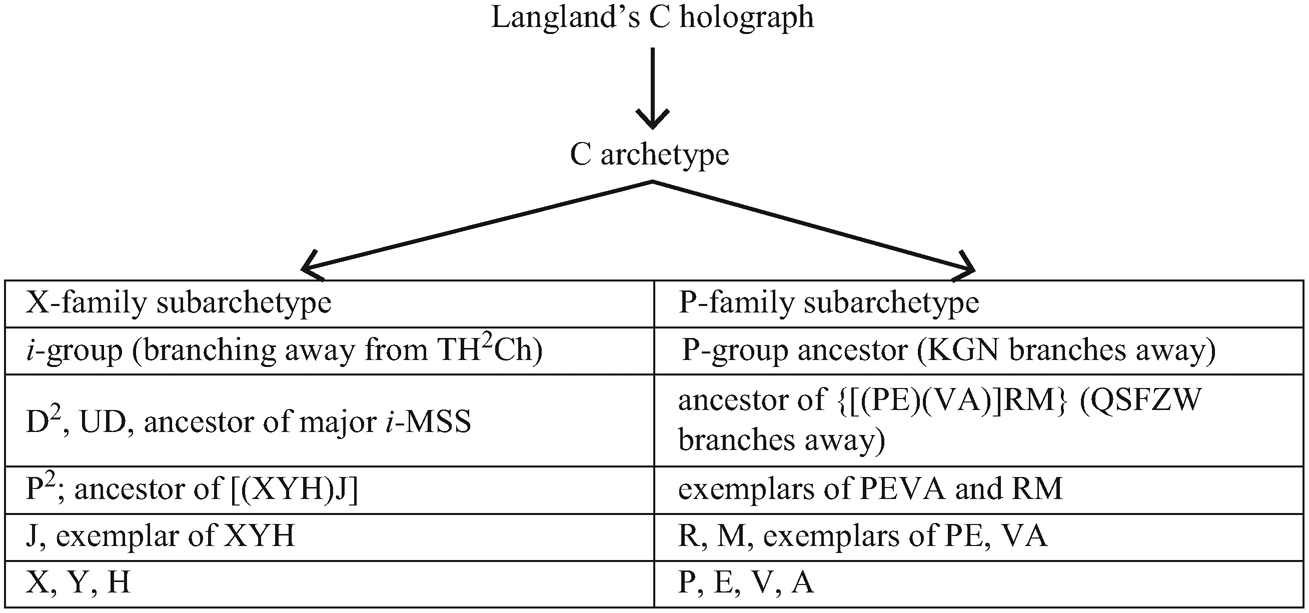

Still lacking is any explanation of why a manuscript's “quality” serves as an index to the location in which its original ancestor was produced. Perhaps those who assume such a correlation believe that the P-group “‘is sophisticated and given to expansion,’ and on comparison with the other groups proves to be lower down the chain of transmission and therefore furthest from the author's original,” as Bessie Allen believed (here summarized by Charlotte Brewer).20 But Russell and Kane have now shown that “there are about 520 family errors in P as against 470 in X,” which means, first, that the X-group is only about 10 percent “better” than the P-group, and second, that both groups introduced many errors from the start: the latter is not “lower down the chain of transmission,” that is, an offshoot of the X-group, at all.21 Both groups' ancestors made copies of the C archetype. And in any case the earliest surviving manuscripts of both the X- and P-groups are roughly seven generations of copying removed from the holograph. In Figure 3, in Russell and Kane's analysis, are the lines of transmission.22 The earliest A copies, too, are separated from that version's holograph by seven generations, which is about double the number between the earliest B copies and that version's holograph.23

Figure 3 Lines of transmission of the two C-text MS families

Yet the belief that the quality of MS X shows it to be closer to Langland than was even the ancestor of the P-group, its own great-great-great-great-uncle, has become the foundation for all discussion of the C version's localization. By this logic, Langland could have been in Cambridge c.1870, when Skeat took a faithful copy from MS J, producing Cambridge, Trinity College MS 536 as he prepared his edition of the C version. However far removed in place or time, scribes could faithfully copy texts. The site of any given manuscript's production, in sum, says nothing about where the poem's author was when he wrote it. It is no surprise that copies stayed in that location, whether in London or opelond, but the only way to reverse the terms is, as George Kane said about the methodologies of attribution, already to know the answer to the question.

Many sundry sorrows: C 3.87–114 and the riot of February 1384

One potential source of evidence for the localization of Piers Plowman C more reliable than dialect might be the transmission history of the B version. Nearly all readers agree that B is a London production, and many of its earliest extant witnesses, observes Robert Adams, “were almost certainly produced in the same place in London, either by a group of Langland's friends or by their immediate successors.”24 If I am right to believe that passus 19 and 20 came into the B tradition from Langland's C papers, then it would seem very probable that C must have been circulating in London by around 1390.25 The question of whether the Londoner Thomas Usk, beheaded in 1388, referred to the C version in his Testament of Love remains open.26 In turning from external to internal indications of Piers Plowman C's site of production and earliest readership, one will immediately be struck by the fact that, as James Simpson notes, “the emphasis changes from Langland as an uplandish figure in the B-Text to Langland as a Londoner in the C-Text (a change consonant with three extra ‘London’ passages in that version).”27 He refers to the apologia pro vita sua (5.1–104), which occurs, says the dreamer, “whan y wonede in Cornehull” (1); 16.286–97, in which he says “Ich have yleved in londone mony longe зeres” (288); and 3.87–114, an exhortation to mayors not to enfranchise false traders. Even so, the presence of these passages has never led critics to assume the necessity of their composition or reception in London.

Yet the final of these extra “London” passages, so I will now argue, responds directly to explosive events on the streets of London in February 1384. That might suggest, but does not necessitate, Langland's presence there; what turns this possibility into a probability is that the passage seems to assume the same knowledge in its readers: if he were referring to an episode that was not common knowledge among his audience (as would likely be the case in the West Midlands, where the bickerings of London's mayors and aldermen would not have been foremost in readers' minds), we might expect a more explicit treatment. The Meed episode of both the A and B versions leading up to this point features a standard moralistic invective against “regraterie,” that is, “buying up food in one market and selling it at an enhanced price in another, which was forbidden by civic custom.”28 In C, though, the narrator's warning becomes part of a full-scale program, in which the biblical prophecy is not just an abstract moral, but a real and terrifying event fulfilled on city streets:

Many times, the narrator continues, the saints beseech our Lord and Lady, on behalf of the suffering innocent, to allow sinners to have their penance on earth, rather than the pains of hell afterwards (97–101). The crucial part of this addition comes next, in the C reviser's elaboration of the pain suffered by the innocent via the actions of a single sinner:

The logic and imagery here look forward, as it happens, to an argument for the legitimacy of the medieval archive by a Reformist and serious reader of Piers Plowman, Stephan Batman, a few centuries on:

He is no wyse man þat for the haveng of spiders. scorpions. or any outher noysom thinge in his howse will therefore set the whole howse on fier: for by that meanes, he disfornisheth himselfe of his howse: and so doo men by rashe borneng of ancient Recordes lose the knowledge of muche learnenge / there be meanes and wayes to presarve the good corne by gathering oute the wedes.30

The parallels indicate how deeply ingrained are the impulses to burn and to archive, whether the agent is a zealous Reformer or God himself, angry at the scorpionesque regrators whom, says Langland's narrator, mayors must keep in check:

The C reviser's whole performance bears an extraordinary resemblance not just to Batman's future work with Archbishop Parker, but also, much more immediately, to the Westminster Monk's account of an event that occurred on the London streets in February 1384, in which a supporter of John Northampton, mayor of London from 1381 to 1383, did indeed cry out for vengeance on the city streets, and lost his head for so doing.31 This riot was the culmination of the unrest that followed the October 1383 mayoral victory of Nicholas Brembre, with the support of the victualing guilds, especially the fishmongers, over Northampton, aligned with the artisanal guilds.32 On the evening of February 7, 1384, says the Monk, Northampton's dinner companion was the young Thomas Mowbray, who asked Northampton to gather some friends that evening and join him at Whitefriars, where his brother had been buried a year earlier.33 Northampton arrived at Whitefriars in the company of some four hundred of his supporters in the artisans' guilds, still angry at the election of Brembre, who had the support of the fishmongers and other victualing guilds. Meantime, news of the gathering came to Brembre as he dined with some aldermen in the house of Sir Richard Waldegrave – whose brother was among those arrested together with “William vocatus LongWyll” for aiding and abetting the murder of Sir Ralph Stafford a year after these riots (Chapter 1).

On the way back, the new mayor, in the company of forty of these partisans, fell in with Northampton, accused him of attempting to incite a riot, and arrested him. Brembre ultimately convinced King Richard to place Northampton under custody in Corfe castle. Four days later, John Constantine, a cordwainer, “excited, as some will have it, by a spirit sent by the Devil, careered through the streets of London urging the populace to rise against the mayor, whom he declared to be bent on smashing all those who supported John Northampton,” writes the Westminster Monk. Constantine implied that Northampton's supporters “should suddenly surprise and destroy” Brembre; but “a righteous and merciful God,”

unwilling that the emergence of serious sedition in the densely populated city should lead, because of a single individual, to people's destroying one another, ordained a better course for events in choosing rather that one man should die than that the innocent blood of the many should be spilled. And so the cordwainer was arrested, and upon his conviction before all the leading citizens of spreading false statements, he was condemned to death in conformity with the law. By order of the court of aldermen his head was set above Newgate.

Constantine's head remained above Newgate for four years, until Brembre's trial in the wake of the Merciless Parliament.34

Two passages, both datable to the mid-1380s; referring frequently to London; focusing on mayoral responsibility, regratery, and divine justice in the streets; and emphasizing the need for civic authorities to act decisively so as to prevent punishment from raining down indiscriminately. Since no indications suggest that either author encountered the other's work, it seems most likely that Langland's revisions were prompted by the same events that brought about the Monk of Westminster's account. The passage in Piers Plowman C passus 3, these parallels suggest, is thus best read not as a general meditation on mayoral responsibilities regarding enfranchisement, applicable anywhere in England, but rather as an insertion inspired by the riot of 1384. And unless the inspiration for this C addition was a late-night conversation between the prisoners Long Will and Warin Waldegrave the following year, the parallels canvassed above seem most easily explained as a London denizen's thoughts intended in the first instance for a London audience.

In the castle of Corfe

Brembre ultimately convinced King Richard to place Northampton under custody in Corfe castle: on its own there is nothing distinctive about that episode. But in the context of the C reviser's additions to the Meed episode, it takes on a different hue. For that matter, Piers Plowman C as a whole, its production and transmission, look different in light of Northampton's imprisonment in Corfe castle. The passage at issue occurs after the insertion discussed above. To this point C has tracked A's and B's presentation of the king's return from his privy council to confer with Meed, upon which he remarks that he has often forgiven her sins in the hopes that she will mend her ways. Then in C appear some new lines:35

The identification of Corfe castle as Northampton's destination by both the Westminster Monk and the compiler of Letter-Book H bolsters the likelihood that this was common knowledge on the streets of the city.36

We have already seen some of the difficulties standing in the way of recognition that these C additions pertain to London's factional politics of the 1380s. Here another one comes to the fore, one that forces hard choices about the status of the “best” manuscripts of Piers Plowman: that in the received text “it is the treatment implied by the words as an ancre that is really important, not the place,” as A. G. Mitchell remarked in an essay published in 1948.37 In this reading “the Castel of Corf ” merely provides handy alliteration with “close,” and does not carry any historical referent or particular meaning in the passage at all. Yet places in Piers Plowman, whether the Malvern hills or Corfe castle, deserve serious consideration before their importance is dismissed. With regard to Corfe, this is especially so given the powerful indications, some never noted before, that as an ancre, the phrase that led Mitchell and all subsequent editors to downplay the reference to Corfe, was probably not in Langland's text at all.

In 1934, F. A. R. Carnegy proposed that the phrase at issue was “a gloss erroneously incorporated into the text”: “So far from improving the line, the words ‘as an ancre’ overload it, and add nothing to the sense; or rather, they make nonsense, for anchorites did not live in castle dungeons.” He speculated that perhaps a reader, prompted by “the thought of the solitude reigning in prisons and in anchorites' dwellings,” wrote the phrase as a marginal annotation. While Carnegy does not say so in so many words, his theory finds support in the location of these three words: “in the MSS. of the i-group they come at the end of l. 141; in those of the p-group at the beginning of l. 142,” a circumstance suggesting that they “were tacked on to the end of l. 141 until the p-tradition, in its revision of the poem, transferred them to l. 142, and, by the addition of ‘And marre þe with myschef ’ made two lines out of l. 142.”38 He concludes by noting that there is good precedent for this phenomenon of scribal incorporation of marginal glosses,39 Skeat's historical suggestions about the phrase are very weak, and the p-group's “‘And marre þe with myschef ’ adds nothing to the sense, and seems to be a pretty certain example of padding.”40 This proposal has garnered only one response: Mitchell's rejoinder that “the possibilities of interference and alteration are so numerous as to provide us with means of explaining away almost anything that does not readily commend itself to us.”41 No modern editors have mentioned the possibility that as an ancre was a scribal gloss.42

Some compelling evidence, though, points to the plausibility of Carnegy's proposal. In received C 3.141–3, the term “anchorite” is singular, the sole referent to the religious life, and part of a quotation. By contrast, all six other appearances are in the plural and occur as a general referent, in juxtaposition with the terms “hermits” or “monks” and in the context of discussions of ethical matters of almsgiving, asceticism, or sex:

1. A/B Prol.28–30; C Prol.30–2:

As ankeres and eremites þat holdeth hem in here sellesCoveyten noзt in contrey to cayren abouteFor no likerous liflode here lycame to plese.- Ankeres and eremites þat holdeth hem in hire sellesShullen have of myn almesse al þe while y libbe . . .

- For of here kynde they comen þat confessours ben nempnid,Bothe maydenes & mynchons, monkes & ankeres,Kynges & knyhtes, & alle kyne clerkis,Barouns & burgeys, & bondemen of tounes.

4. B 6.145 / C 8.146 (following two lines revised from B > C):

Ankerus and eremytes þat eten but at nones . . .- For he lyveth nat in lolleris ne in londleperis eremytesNe at ankeres þere a box hangeth; alle swiche they fayten.

- Ankerus and eremytes and monkes and freresPeeren to apostles thorw hire parfit lyvynge.43

So too is the term's spelling of ancre in MS X, whose language is generally deemed closest to the poet's,44 unique: it is anker- in both other appearances. As Horobin shows, this manuscript's scribe was among a group “who were careful to preserve many of the features of dialect and spelling associated with the author”;45 if anker was indeed the author's spelling, then ancre at 3.143 looks all the more like a scribalism taken up into the text and reproduced faithfully.

The case finds further support on the grounds of sense. Mitchell insists that it is “not relevant to point out discrepancies between the situation described by the poet, and the known facts as to purpose, method and place of the normal enclosure of anchorites. This is a special case and since the purpose and manner are different, we are hardly at liberty to argue from something out of the ordinary as to place.”46 To bolster this remarkable stance he attempts to explain as an ancre in light of a theory of punishment: “sure that an experience of the loneliness and strictness of the anchorite's life would sober Meed and turn her honest,” he writes, the king wishes “not merely to punish her, and dispose of her, but to reform her.”47 In this reading as an ancre means “in the manner of an anchorite (which you will not really be),” but that is problematic. The seemingly analogous phrases, in which Will dresses “in abite as an heremite” (C Prol.3) or is “yclothed as a lollare” (C 5.2), are not really, as there can be no doubt there that “as (if I were)” is understood.48 And Langland could easily have avoided the ambiguity this approach necessitates: “as y a shep were” (Prol.2); “Thus is man and mankynde in maner of a sustanyf ” (C 3.404); or, as in Fals-Semblant's boast in the Romaunt of the Rose, “Somtyme I am religious; / Now lyk an anker in an hous” (6347–8).

Questions of language aside, Mitchell is quite right about the king's desire to reform Meed, but has the means by which he can do so backwards: incarceration alone was sufficient for the purpose; enforced anchoritic enclosure impossible. “Penitential literature had early recognized that forced confinement could furnish opportunities for reflection upon past misdeeds and a change of heart,” as Ralph Pugh says, “and this seems, at least sometimes, to have been the motive for imprisoning monks and nuns.”49 The case of a certain Matilda, an anchoress accused in 1389 of being “infected” with the harmful teachings of the Lollards, proves the point. When Matilda, under interrogation by Archbishop William Courtenay, responded not plainly but potius sophistire, he commanded “that the door of the recluse, in which the said Matilda was, should be opened, and that till his return he should cause her to be put in safe custody” – in “a veritable prison,” says Mary Rotha Clay, for whose stone walls Matilda exchanged her own “under compulsion.”50 Upon returning from her prison to her cell, Matilda recanted her heretical beliefs and the archbishop issued a mandate offering indulgences for those who came to her aid.

By contrast, anchoritic enclosure was the result, not the cause, of penance. It is the status from which Matilda is removed. The “essential feature” of the rite of enclosure “was the forgiveness of all the sins of the person about to be enclosed, a ritual death and burial, and the beginning of a new life in the anchorhold, beyond earthly sinfulness.”51 Thus no bishop or king could force a woman to become an anchorite.52 Those thus enclosed were no pariahs, a status Langland's king enjoins on Meed, but icons of holiness: “Admitted into the company of angels, they might then be allowed by God to see heavenly wisdom, to acquire true prophetic knowledge,” in Anneke Mulder-Bakker's words. “They lived at an intersection of heaven and earth and incarnated the salvation that flowed to that place. With them people found a ray of happiness in this earthly vale of tears. The reputation of recluses was beyond question.”53

All of the above has engaged with the debate on the terms in which it was set, terms that would appear to remain in effect given the presentation of the data in all editions of Piers Plowman. But this is the product of an incomplete Langland archive. For these lines appear as well in another manuscript whose version has never been printed: National Library of Wales MS 733B (N of A / N2 of C),54 whose C material, crucially, is a witness to that version's archetype independent of, and earlier than, the two major manuscript groups.55 Among the C matter conflated into N's A-text portion is this: “In þe castel of corf I schal done þe close / Or ellis in a werse wone by sent marie my ladye.” Now, it is possible that the absence of our phrase here is the result of a scribal oversight. Yet to dismiss this new witness to the passage on such grounds would be to acknowledge the validity of Carnegy's approach to the i- and p-traditions. Mitchell had objected that we have no right to such appeals unless the text is “mangled,”56 yet the sense of this text's reading is perfectly clear: precisely the one that Carnegy conjectured to be authorial even though he could not have known of this reading.57 It is true enough that the meter is faulty, the line's aa/xa scansion – castel, corf, þe, close – transgressing the aa/ax norm, but this is no stumbling block. It is simple enough to reverse the final two terms, as does Russell and Kane's text, and in any case the existence of passages like C Prol.95–124, new material that barely attempts to maintain normative alliteration, should prevent too quick an appeal to such standards as prerequisites of authenticity. An aa/xy line like the second here could well have been a placeholder for the poet.

It is an impossible situation, which no appeal to the authority of the received text over the presumptuous modern critic will help. As the opelond vs. up london dilemma also showed, this is a matter of judgment. The power of the archive will not suffice on its own. Mitchell's judgment that it is the treatment implied by the words as an ancre that is really important, not the place, has had an indelible impact both on the received text of Piers Plowman and, more important, on the process of localization via its occlusion of potentially (or, as I take it, actually) relevant evidence. Yet there are no good reasons to accept these words as authorial, many reasons to reject them, and concrete support for the alternative, that the king threatens imprisonment proper in Corfe castle, which fits the context perfectly. To date commentators have focused upon this location as the reputed site of Edward II's incarceration and possibly murder, though Skeat does as well suggest a connection with a thirteenth-century hermit who together with his son was hanged there for his evil prophecy to King John.58 Yet this is quite far, chronologically and thematically, from the drama of Piers Plowman C passus 3. The events of February 1384, by contrast, are both quite close and appropriate to the context, which, after all, is about mayors, meed, and punishment.

Conclusion: toward a textual historicism

If Piers Plowman C had already been determined to be a London production, would modern readers have proposed the existence of these allusions long ago? It is difficult to know the degree to which Langland's reputation as a poet “in opelond,” far from London, fueled the notion that “the only difference between C and the earlier versions” in the matter of fair trading, as E. Talbot Donaldson said, “is C's elaboration, upon lines already laid down in A and B, of a passage castigating dishonest retailers,”59 that is, that nothing distinguishes C 3.87–114 from its B equivalent. More recently, James Simpson's argument that Langland engages intensively with London city politics, and particularly that he supported Northampton and the artisanal guilds, likewise says nothing about C. Simpson cites the animosities of the 1380s to lay out the situation, but, because of the supposed fact that at that point in time Langland was in the West Midlands, and the supposed “B” home of Simpson's textual evidence, he finds himself having to claim that it is instead the political situation of 1376 that is relevant.60

The passage at issue is the episode of the distribution of the gifts of Grace, which imagines the resolution of the trade rivalry between the artisanal and victualing crafts as a model for the renovation of the church:

While Grace here imagines unity of “crafts,” which Simpson plausibly takes to mean “guilds,” nevertheless “Langland's picture is not innocent, or naïve, as read in the context of contemporary politics,” he notes; “it is clearly angled in favour of the reformist party [of Northampton], in favour, that is, of ‘Craftes Counseil’.”61 The need to look elsewhere than the immediate historical context for this compelling claim, the Brembre/Northampton disputes of c.1384, exemplifies the ways in which arbitrary elements of the Langland archive have forced its interpreters onto unnecessary detours. In this case, new evidence that passus 19–20 entered B from C shows that Simpson's insight was even stronger than he could have known, and there was no need to look anywhere other than the obvious time and place, the London of 1381–4, to make sense of Langland's engagement with regratery and the guilds.62

None of the above analysis is to say that the passage is “anti-Northampton,” or that readers are to take these lines as a mini-allegory of London political strife. It would be a mistake to make too much of the connection of Meed and Northampton, not just because the king does not come off so well himself, but also because Langland exhibits so little interest in maintaining dramatic consistency in this portion of the poem. J. A. W. Bennett even proposed that the lines on regratery common to all versions “represent an officious scribe's intrusion or a fragment of a larger episodic discourse that was missing from, or never completed in, the Ur-text,”63 a sense amplified in the C version: 3.77–114, comments Derek Pearsall, “was never clearly related to the context in AB,” with a repetition of line 77 at line 115 that “only emphasizes its digressive nature.”64 The same could be said of 141–6 on a smaller scale. The likeliest scenario for the production of C passus 3 is that, living in London in the 1380s, Langland could hardly help seeing the pertinence of his earlier invective against shoddy victuallers and corrupt mayors to what was transpiring on the streets of the city, and that he wrote up some new passages on separate sheets, which could circulate independently of the poem, to be inserted into Piers Plowman as it stood at that stage.65 In this scenario early readers would have experienced the C version as a disjointed piece of work, with the narrative framework (for instance, Lady Meed's visit to Westminster) at times disappearing entirely while the narrative voice goes in other directions (as in the invective against victualers and irresponsible mayors).

Even if my proposal is the best explanation of the parallels between Langland's and the Westminster Monk's works, it is not inevitable. But such a qualification is necessary only because of the prior assumption that Langland was across the country in the 1380s. What I am here urging, then, is the institution of a textual historicism, one that subjects all the available evidence for the manuscripts' histories, especially their texts, to critical scrutiny, rather than determining in advance that some are “better.” The old controversy over as an ancre, and, even more so, the disappearance of that controversy, are cases in point. The abandonment of the subservience to copy-text also has the beneficial product of a sharpened understanding of the roles played by early scribes and readers. Even though “the glosses found in the MSS. are not often distinguished either by their brilliancy or by their lucidity,” as Carnegy says, the instance here identified provides a newly apparent record of how one of its very earliest readers responded to the poem.66

My main goal is to promote recognition of the power accorded assumptions about the Langland archive that are somewhat arbitrary, the products more of certain stages in twentieth-century literary criticism than any analysis of the pertinent evidence. If, for instance, it were determined that my own proposals were no less arbitrary than those that led earlier generations to locate Langland where the best C extant manuscripts were produced, we would be left nowhere – literally, which is as it should be in such circumstances. This is just another way of saying that localization, which has so often relied on such technical methodologies as dialectology, is not something external and prior to interpretation, as we so often take the constituent elements of the archive to be: it is interpretation itself.