Since the pioneering study by Crick and Grotpeter (Reference Crick and Grotpeter1995), relational aggression, defined as a behavior that harms others through manipulation of interpersonal relationships, has gained considerable attention among researchers, clinicians, educators and policymakers. As such, a relational form of aggression has been widely examined in familial, educational and clinical settings and shown to be a developmentally salient factor for cognitive, emotional and social adjustment (for a review, see Murray-Close, Nelson, Ostrov, Casas, & Crick, Reference Murray-Close, Nelson, Ostrov, Casas, Crick and Cicchetti2016). However, the majority of studies in this area of research have been conducted in Western cultures. Indeed, several promising studies in Asian cultures showed some similar effects of relational aggression (e.g., Kawabata, Crick, & Hamaguchi, Reference Kawabata, Crick and Hamaguchi2010; Kawabata, Tseng, Murray-Close, & Crick, Reference Kawabata, Tseng, Murray-Close and Crick2012; Lee, Reference Lee2009; Li, Wang, Wang, & Shi, Reference Li, Wang, Wang and Shi2010; Nelson, Hart, Yang, Olsen, & Jin, Reference Nelson, Hart, Yang, Olsen and Jin2006). Yet, the clear and full understanding of relational aggression and its effect on forms of psychopathology in a specific cultural context, such as Asian-Pacific Islands, is still lacking. This gap in the literature is problematic as leading scholars suggest that the social context of culture should be incorporated in the evaluation of peer aggression and victimization (Ostrov & Kamper, Reference Ostrov and Kamper2015) and psychopathology (Causadias, Reference Causadias2013). The present study addressed this limitation in the literature and examined how relational aggression is associated with depressive symptoms in the culturally diverse environment of Guam.

Guam is a U.S. territory that consists of people from Pacific Islander and Asian descent. Guam has a history of colonization by the Spanish, Japanese and Americans, which has deeply influenced Guam’s culture. Although the influence of Westernization has led to the loss of some indigenous cultural practices, the collectivistic nature of Guam’s culture (e.g., the emphasis on family obligation, interdependence and respect for elders) is still predominant (Nakamura & Kawabata, Reference Nakamura and Kawabata2018). Inafa’maolek, the concept of interdependence and restoring peace or harmony within the family and community, impacts the way the people of Guam interact with others on a daily basis. This concept manifests within this population through family gatherings, fiestas and responsibility to extended family members, such as financial support, household tasks and considerations in decision making. In such collectivistic, traditionally family-oriented cultures, relational aggression is thought to be deemed developmentally more salient (i.e., more harmful on mental health) as opposed to physical aggression, since relational aggression is a more subtle form of aggression to react to interpersonal relationships (Kawabata, Reference Kawabata, Coyne and Ostrov2018).

The goal of the present study is to examine the association between relational aggression and depressive symptoms among emerging adults in Guam and whether relational victimization and attachment insecurity mediate this association. Given that relational aggression is more commonly directed at women than men and its effect is more pronounced among women than men (Crick, Ostrov, & Kawabata, Reference Crick, Ostrov, Kawabata, Flannery, Vazsonyi and Waldman2007), gender differences in the effect were also explored.

Relational Aggression, Depressive Symptoms and Close Relationships

Theory and research suggest that relational aggression (e.g., ignoring, social exclusion, rumor spreading, silent treatment) is often observed in relationships with significant others (parents, peers, close friends, and romantic partners; Murray-Close et al., Reference Murray-Close, Nelson, Ostrov, Casas, Crick and Cicchetti2016). Relational aggression is different from physical aggression or violence in terms of their forms. The former is a behavior that damages others through interpersonal manipulation, and the latter is a behavior that harms others via physical force (e.g., hitting, kicking and beating). In a comprehensive meta-analytic review, Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, Van Ijzendoorn, and Crick (Reference Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, Van Ijzendoorn and Crick2011) showed that relational aggression is commonly used as a means for parenting within parent-child relationships. Grotpeter and Crick (Reference Grotpeter and Crick1996) indicated that relationally aggressive youth tend to form friendships characterized by high levels of intimacy and exclusivity. Similarly, Murray-Close, Ostrov, and Crick (Reference Murray-Close, Ostrov and Crick2007) found that relational aggression and friend intimacy covaried during an academic year. Linder, Crick, and Collins (Reference Linder, Crick and Collins2002) demonstrated that relational aggression frequently occurred within the romantic relationships among college students and was positively correlated with the negative quality of romantic relationships. Likewise, Goldstein, ChesirTeran, and McFaul (Reference Goldstein, ChesirTeran and McFaul2008) showed that both males and females used relational aggression and experienced relational victimization within their close relationships, characterized by high levels of exclusivity and anxious attachment. Overall, relational aggression can form and develop in parent-child relationships, friendships and romantic relationships that are close and intimate in nature.

Relational aggression also has been shown to be associated with social-psychological adjustment problems (Murray-Close et al., Reference Murray-Close, Nelson, Ostrov, Casas, Crick and Cicchetti2016). Research evidence from a meta-analytic study, which mostly included Western samples, demonstrated that relational aggression was predictive of higher levels of internalizing adjustment problems, including anxiety and depressive symptoms, even after the contribution of physical aggression was controlled for (for a review, see Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, Reference Card, Stucky, Sawalani and Little2008). Similarly, Kawabata et al. (Reference Kawabata, Crick and Hamaguchi2010) and Kawabata & Crick (Reference Kawabata and Crick2013) showed that the association between relational aggression (but not physical aggression) and depressive symptoms (but not delinquency) was robust among adolescents in Asian countries such as Japan and Taiwan. This unique, stronger association has been replicated among Asian-American youth in the United States (Kawabata & Crick, Reference Kawabata and Crick2013), suggesting the possibility of cross-cultural similarity in terms of the relational aggression-depression linkage.

Rudolph et al. (Reference Rudolph, Hammen, Burge, Lindberg, Herzberg and Daley2000) suggested that depression is often generated from an interpersonally stressful context (e.g., negative peer relationships), especially after adolescence when relationships become central to children’s socialization. This theory may explain why relational aggression is particularly linked to internalizing adjustment problems. In support of this view, Rudolph et al. (Reference Rudolph, Hammen, Burge, Lindberg, Herzberg and Daley2000) showed that clinically referred youth were more likely to acquire internalizing problems due to interpersonal chronic stress than non-interpersonal stress. In turn, relational aggression is thought to be a robust, peer-linked stressor as it is viewed as aversive by peers; that is, relational aggression predictably puts youth at risk for peer rejection, low social status or unpopularity, and peer victimization (Crick et al., Reference Crick, Ostrov, Kawabata, Flannery, Vazsonyi and Waldman2007). All of these social factors that covary with relational aggression are significant risk factors for depressive symptoms (Murray-Close et al., Reference Murray-Close, Nelson, Ostrov, Casas, Crick and Cicchetti2016).

A Mediation Model of Relational Aggression and Depressive Symptoms

The association between relational aggression and depressive symptoms has been established; however, relatively little is known about how and why relationally aggressive youth develop more or less depressive symptoms. One possible factor that may explain this gap is an experience of peer victimization, particularly relational victimization. Relational victimization is a negative peer experience by which an individual becomes a target of relational aggression (e.g., being ignored, socially excluded; Murray-Close et al., Reference Murray-Close, Nelson, Ostrov, Casas, Crick and Cicchetti2016). Abundant evidence suggests that relationally aggressive youth often experience relational victimization concurrently and longitudinally, presumably due to their manipulative characteristics and behaviors toward their peers (Kawabata, Reference Kawabata, Coyne and Ostrov2018). Although relational aggression can be linked to high social status (i.e., peer acceptance and popularity), a cost of using relational aggression is relatively high (Heilbron & Prinstein, Reference Heilbron and Prinstein2008). A developmental process for this phenomenon is that relationally aggressive youth are inclined to be disliked and socially excluded by their peers over time due to the aversive nature of their behavior. One possible mechanism is that these youth, if successful, can be viewed as a queen or popular at the moment, but once they are unable to maintain the high social status and likability among their peer group, they are subjected to their peers’ censure along with revengeful feelings, jealousy and resentment. In a longitudinal study, Kawabata, Tseng, and Crick (Reference Kawabata, Tseng and Crick2014) showed that the development of relational aggression and experiences of relational victimization were influenced by each other over time; that is, relational aggression predicted increases in relational victimization and vice versa. In turn, peer victimization, particularly relational victimization, has been shown to be a robust risk factor for internalizing adjustment problems (Casper & Card, Reference Casper and Card2017).

Attachment is another relational factor that needs to be considered in the link between relational aggression and depressive symptoms within a close relationship. In a comprehensive review of attachment, Michiels, Grietens, Onghena, and Kuppens (Reference Michiels, Grietens, Onghena and Kuppens2008) theorized that lack of a secure base or a maladaptive internal working model is associated with the development of relational aggression. One mechanism behind this model is that if youth develops secure attachment, which is a foundation for forming healthy relationships, they feel safe in the relationship, view their relationship positively and optimistically, and acquire social competence to cope with challenges they may face. These youth may be less likely to use relational aggression as they view their friends and/or partner as a trustworthy, dependable agent, and are able to form healthy, supportive relationships. Consistent with this view, Kawabata et al. (Reference Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, Van Ijzendoorn and Crick2011), in a meta-analytic study, showed that secure attachment predicted less parent-child/adolescent relationships that involve relational aggression. In contrast, insecurely attached youth may be often concerned about their relationship (anxious type) or afraid to make a full commitment to the relationship (avoidant type). Insecure youth may fail to develop closeness, trust and mutual responsibility in their relationship and even tend to use relational aggression when they encounter conflicts, disagreements or any other problems (Nakamura & Kawabata, Reference Nakamura and Kawabata2018). These views suggest the link between relational aggression and attachment insecurity. In sequence, insecure attachment has been shown to be strongly associated with internalizing adjustment problems (for a review, see Groh, Roisman, van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Fearon, Reference Groh, Roisman, van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Fearon2012). Overall, it is possible that relational victimization and attachment insecurity may mediate the link between relational aggression and depressive symptoms.

The Role of Gender

Theory and research suggest that gender plays a crucial role in cognition, emotion and relationships. In a comprehensive review about the role of gender in the self, Cross and Madson (Reference Cross and Madson1997) discussed that women are thought to be more relational-interdependent than men and this gender difference influences the way they think, feel and behave in close relationships. In the same vein, Rose and Rudolph (Reference Rose and Rudolph2006) documented that relative to men, women place more emphasis on interpersonal relationships, care more about significant others, and are more vulnerable to negative interpersonal experiences. Furthermore, Crick et al. (Reference Crick, Ostrov, Kawabata, Flannery, Vazsonyi and Waldman2007) contended that women, who are more interpersonally oriented, are more inclined to utilize relational aggression than men when they are upset about their significant others, and more at risk for internalizing adjustment problems. Correspondingly, research showed that women tend to form friendships, that are closer, more intimate and more exclusive, exhibit higher levels of relational interdependence, use more relationally oriented aggression, and find negative interpersonal events such as relational aggression and victimization more stressful (Rose & Rudolph, Reference Rose and Rudolph2006). Given the stronger relational orientation and vulnerability to women, the effect of relational aggression on depressive symptoms and the mediation of relational victimization and attachment insecurity may be more pronounced for women.

The Present Study

The present study investigated the association between relational aggression and depressive symptoms among emerging adults in Guam and whether relational victimization and attachment insecurity mediate this association. Gender differences in the association and mediation were also explored. Given the dearth of research on relational aggression in Asian-Pacific Islands such as Guam, we conducted an exploratory pilot qualitative study first. The purpose of this pilot study was to understand the participants’ thoughts and feelings by exploring their personal lived experiences regarding aggression and victimization in close relationships, using a semistructured interview (Creswell, Reference Creswell2013). Specifically, participants were asked to express their honest feelings and thoughts about how they respond to the negative situations involving significant others. The following exploratory research questions were employed:

1. Do emerging adults in Guam use aggression, especially relational aggression, when they are upset about their significant others?

2. How do emerging adults in Guam feel when they use aggression, especially relational aggression?

A second, quantitative study examined the mediating roles of relational factors, including relational victimization and attachment insecurity. Based on the literature review, the following hypotheses were generated.

1. Relational aggression is associated with depressive symptoms among emerging adults in Guam; however, this association is mediated via relational factors. In other words, relational aggression is associated with higher levels of relational victimization and attachment insecurity, which in turn leads to greater levels of depressive symptoms.

2. The association between relational aggression and depressive symptoms and the mediating effects of relational victimization and attachment insecurity are more pronounced among women.

STUDY 1: A PILOT QUALITATIVE STUDY

Method

Participants

Thirty-five students (n = 8 and n = 27 for males and females respectively) were recruited from different academic classes at the public university in Guam. The gender composition of the participants and the student body of the university were comparable. The mean age of the sample was 21.1 (SD = 1.7) with the participants ranging in age from 18 to 25 years. The distribution of ethnicity was Chamorro (34.3%), Filipino (31.4%), Caucasian (8.6%), Chinese (5.7%), Mixed (17.1%), and Other (2.9%). The average length of residence in Guam was 16.1 years (SD = 7.5) with a range from less than 2 years to more than 24 years. The majority of participants were in a committed relationship (54.3%) and other participants were single (42.9%) or married (2.9%).

Measures

Demographic information

Participants reported their age, gender, ethnicity, relationship status, number of children, number of siblings, occupational status, college major, and length of stay in Guam.

Semistructured interview

Twenty-nine open-ended, semistructured interview questions were used to identify participant’s honest feelings, beliefs and lived experiences regarding aggression and victimization in a close relationship. The interview questions were created to answer two main research questions mentioned earlier. After the interviewers defined relational and physical aggression and victimization, they asked participants questions about their experiences with their parents, friends or partners. Sample questions included “Can you think of a time when you used relational aggression [or physical aggression]?” “Can you tell me how you felt when you used relational aggression [or physical aggression]?” “Looking back at those times when you used relational aggression [or physical aggression], why do you think you reacted this way?” These questions were developed and evaluated by multiple experts in clinical, social and developmental psychology.

Procedure

Participants were contacted via email and invited to meet for an interview that lasted approximately one hour in one of the conference rooms in the university library. Participation in this study was open to all students regardless of their prior experiences (there was no prescreening phrase). Prior to the interview, participants were asked to read through and sign a consent form, audio-recording authorization form, and cover letter. Participants were told that they could stop the interview any time they wanted without penalty. Those who appeared distressed were informed on how to access free psychological services at the university. After explaining their rights and the risks and benefits associated with the study, the interview started. The data obtained from the interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Transcriptions were stored in a secure and password-encrypted computer database. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the authors’ university.

Qualitative Data Analysis

We formed a research team to collect, transcribe and analyze the data. The research team consisted of three individuals (one female, two males; Asian Americans) who are proficient in conducting research in clinical, developmental and cultural psychology. The first author, a university professor who has extensive research experience in psychology was the principal investigator. The other team members were graduate students in clinical psychology. Before creating the interview questions and collecting the data, the principal investigator trained the team members to conduct an exploratory phenomenological qualitative study. Team members met regularly to discuss how to frame questions regarding relational aggression, close relationships, and mental health in a cultural context, specifically in Guam. Then, the researchers disclosed their personal experiences and assumptions regarding the topic of the study, which helped them to agree on interview questions, coding, and interpreting results. Interviews were conducted by two of our research members (one male and one female). The interviewer was assigned to the participants randomly.

Each transcript was analyzed using the guidelines for conducting qualitative research (Creswell, Reference Creswell2013). Each of the three research team members read all the transcripts and met together to discuss and generate themes based on the pattern of occurrences. After each research member read the first two transcripts that were randomly selected, they met and discussed the possible main themes that may emerge for the rest of the transcripts. These themes included “relational aggression and victimization”, “physical aggression and victimization”, “interpersonal stress and negative emotion”, and “culture”. Then, each team member read each transcript independently and coded each statement (over 500 sentences) into one of the four themes. If each identified different patterns of occurrence that should consist of other themes, we would recode all transcripts. No other themes emerged after all. After coding all transcripts, interrater agreement (90%) was calculated. Sentences which they disagreed with were discussed and clarified to reach an agreement on one theme.

Results

In the following sections, each theme was discussed with direct quotes. Pseudo names were used to protect the participants’ identity.

Theme 1: Relational Aggression and Victimization (n = 35 for Current Episodes)

All students who participated in this study reported their current use of relational aggression, and many of them had experienced relational victimization. Some expressed that relational aggression was very common in Guam, but they did not think that it was aggression. They seemed to be open to talking about their experiences about relational aggression partly because they thought that relational aggression was milder and less harsh.

Relational aggression

Students reported that they often used relational aggression through ignoring, using silent treatment, excluding someone, talking about mean things behind other’s back, and threatening to end romantic relationship. The majority of them stated that they ignored their significant others, did not talk to them, and avoided interacting with them. Some students mentioned that they did not talk for a couple of days or waited until their partner speaks to them. Other students said that they intentionally avoided talking with a particular friend, whereas they talked with other friends, so the victim could see and think that they were excluded. Kate, a 20-year-old female, shared, “I did it to my roommate because she and I were, um, arguing over the house, like house things, like moneywise ‘cause we had to pay rent. So, then, we both ignored each other.”

Relational victimization

The majority of students shared their personal experiences of relational victimization, such as being ignored, excluded, and treated as being invisible by their partner. There seems to be a more indirect, subtle nature of relational victimization than direct relational victimization in Guam. Similar to relational aggression, most students’ experiences of relational victimization were current and embedded in friendships and romantic relationships. Joe, a 21-year-old male, shared, “My current girlfriend, she wouldn’t try to hurt me physically. Instead she just said things behind my back.”

Overall, the findings of this theme indicate that students in Guam may use relational aggression as a perpetrator, and concurrently, they may be a victim of relational aggression.

Gender differences in relational aggression and victimization

The majority of our female participants reported experiences of both relational aggression and relational victimization. Although our male participants reported experiences of relational victimization (mostly from their cross-sex partner), very few mentioned using relational aggression.

Theme 2: Physical Aggression and Victimization (n = 9 for Current Episodes and n = 12 for Childhood Episodes)

Although all experiences about relational aggression that students shared were current, many of the episodes about physical aggression (e.g., fights with parents at home and peers at schools, hitting and kicking siblings) and physical victimization (e.g., harsh punishment by parents, being hit, kicked, and yelled by siblings) were in childhood.

Physical aggression

The majority of our participants seemed to be extremely hesitant to disclose their experience of using physical aggression even after an interviewer fully explained the differences between physical aggression and domestic violence and provided concrete examples. Eventually, some of them shared using physical aggression with other family members. Shane, a 19-year-old female, shared, “I guess with my sister, she said some things that I didn’t like and it upset me ‘cause it wasn’t true, but she was just like, she kept bringing up and bringing it up and then, I pushed her.”

Physical victimization

Among our 35 participants, only several students confessed that they experienced physical victimization from other family members. However, they justified that physical victimization was typical in a family household (e.g., disciplinary parenting style, typical sibling fights) in Guam. Leslie, a 22-year-old female, shared, “Maybe my – just my mom, like, you know, parenting style is just spanking and stuff like that, yeah.” Surprisingly, the majority of participants’ experiences of physical aggression and victimization occurred with other family members. They generally saw their experiences of physical aggression and victimization as either “discipline” from their parents or “rough-and-tumble play” with their siblings.

Gender differences in physical aggression and victimization

Findings in this theme demonstrated that both females and males used physical aggression when they were upset about their significant others; however, the number of such episodes was very low.

Theme 3: Interpersonal Stress/Negative Emotion (n = 34)

Our coding revealed two subthemes under this theme: internalizing problems and externalizing problems. When our participants were asked how they felt after using forms of aggression and receiving forms of victimization, the majority reported negative emotions.

Internalizing problems

As expected, the majority of our participants felt sad or lonely when they experienced victimization, particularly relational victimization. Interestingly, several participants said that they also felt guilty after they used relational aggression. Ana, a 22-year-old female, shared, “I remember always feeling guilty afterwards, like, I actually inflicted some kind of harm.”

Externalizing problems

Similarly, some of our participants shared a feeling of frustration toward their aggressor after receiving relational or physical aggression. However, most of our participants argued that they typically used relational or physical aggression out of anger and frustration with their significant other. Liz, a 22-year-old female, shared, “Oh, extremely angry. I was super mad with her and it’s like this blind fury kinda thing. And, like, I couldn’t, I felt like I couldn’t control myself so I, like, automatically did that as a reaction to the situation.”

Overall, our findings under this theme revealed various negative emotions felt by our participants who experienced victimization, particularly relational victimization. This theme also revealed that relationally or physically aggressive individuals felt negative emotions after they inflicted such aggression. These findings suggest that relational aggression and victimization may be risk factors for developing mental health problems.

Gender differences in interpersonal stress/negative emotions

Our overall findings in this theme highlighted gender differences in expressing emotions. The female participants reported their negative emotions when they used relational aggression and experienced relational victimization. Their description about emotions were more detailed than males’. The male participants expressed their negative emotions as well, but their episodes were rather short.

Theme 4: Culture (n = 11)

When students were asked why they used or received relational victimization, our coding uncovered two culturally related subthemes: collectivism-individualism and perceived discrimination.

Collectivism-individualism

Since Guam is inhabited by diverse ethnic immigrants, some students mentioned that relational aggression was common in a collectivistic or family-oriented culture such as Guam. Participants also shared that relational aggression may be seen as “less serious” in this type of culture than physical aggression. Carla, a 20-year-old, female, shared, “I think it exists in society, even, and I feel like, um, even though people know that it exist – they have this – like the blind eyes to ignore it because in this, in the place where we live in, it’s always ‘mind your own business’.”

Perceived discrimination

Some students mentioned that they were relationally victimized because they were not originally from Guam. Some of the participants shared that they were socially excluded because of their skin color. None of our participants reported receiving physical aggression because of their ethnic identity. Jenny, a 19-year-old female, shared, “feel like it was a race thing ‘cause they made up this disease or whatever, and it was called [name calling against White girls]. And they used to write it on the boards and stuff—the teachers didn’t know what it was.”

Overall, our findings from this theme suggest that cultural factors may contribute to individuals’ experiences of relational victimization in Guam. Although physical aggression may not be common for immigrant students, our participants personally shared mostly discriminatory related relational aggression inside the campus. These negative experiences may be linked to immigrant students’ culturally related stress (acculturative stress), which may lead to serious mental health problems.

Summary

In the pilot, qualitative study, we learned that emerging adults in Guam often use relational aggression and experience relational victimization, thereby exhibiting negative emotions. These findings inform us of the existence of relational aggression and the possibility of its linkages with emotional problems, such as depressive symptoms. Given that relational aggression episodes are often embedded within negative close relationships (e.g., abusive, conflictual, or enmeshed), it is possible that relational aggression may be associated with relational victimization and insecurely attached relationships. Considering these views, we theorized a model involving relational aggression as a predictor, relational victimization and attachment insecurity as mediators, and depressive symptoms as an outcome variable, and tested the viability of the model in the next study for females and males.

STUDY 2: QUANTITATIVE STUDY

Method

Participants

Participants were 206 students (n = 66 and n = 140 for males and females respectively) from the University of Guam. The mean age of the sample was 20.02 (SD = 1.80) with the participants ranging in age from 18 to 25 years. The majority of participants were single (61.2%), and others were either in a committed relationship (37.9%) or married (1%). The ethnicity distribution included Filipino (40.8%), Chamorro (24.8%), Palauan (4.9%), Yapese (4.4%), Caucasian (2.9%), Korean (2.9%), Chinese (1.5%), Pohnpeian (1.5%), Chuukeese (1%), Mixed (12.1%), and Other (0.5%). The average length of residence in Guam was 14.75 years (SD = 7.213) with a range from less than 1 year to 25 years.

Measures

Demographic information

Participants provided information regarding their age, gender, ethnicity, relationship status, number of children, number of siblings, occupational status, college major, and length of stay in Guam.

Relational and physical aggression and victimization

The Self-Report of Aggression and Social Behavior Measure (SRASBM; Linder et al., Reference Linder, Crick and Collins2002) was used to assess relational and physical aggression and relational victimization. This scale consists of items that were rated on a scale of 1 (not at all true) to 7 (very true). SRASBM was used to produce four subscale scores (relational aggression, relational victimization, physical aggression, and physical victimization). Sample items for relational aggression and victimization include: “When I want something from a friend of mine, I act ‘cold’ or indifferent towards them until I get what I want” and “When I am not invited to do something with a group of people, I will exclude those people from future activities”. Sample items for physical aggression and victimization include: “I try to get my own way by physically intimidating others” and “I have a friend who has threatened to physically harm me in order to get his/her own way”. The SRASBM demonstrated high internal reliability (αs > .90).

Attachment insecurity

Participants were asked questions related to their levels of attachment insecurity (attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety) on the Experiences in Close Relationships – Revised Scale (ECR-R; Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, Reference Fraley, Waller and Brennan2000). The ECR-R is a 36-item Likert-type scale rating their level of agreement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items include: “I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me” and “I don’t feel comfortable opening up to romantic partners”. The ECR-R demonstrated high internal reliabilities (α= .91; α= .94) for the anxiety and avoidance subscales.

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977) is a 20-item scale that measures depressive symptoms. Sample items include “I felt lonely” and “My sleep was restless”. Participants rated the frequency of their depressive symptoms during the past week from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (all of the time). Thw CES-D demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .89).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from different academic classes at the public university in Guam. This study was approved by the IRB at the authors’ institution. Participants were given a website via Qualtrics to access the consent form, cover letter and survey measures, which took approximately an hour to complete. Participants were notified that they could stop answering the questionnaires any time they wanted without penalty. They were asked to read through and sign an IRB-approved consent form and cover letter that included instructions and contact information about the university’s free psychological services if the questions were bothering them. After explaining their rights and the risks and benefits of the study, they could proceed to answer the survey.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables by gender are shown in Table 1. For women, relational aggression was positively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = .27, p = .03). However, for men, relational aggression was not significantly correlated with depressive symptoms (r = .21, ns). Attachment anxiety, attachment avoidance, and relational victimization were positively correlated with depressive symptoms for men and women (rs = .18-.42, ps < .05). Relational aggression and attachment anxiety were positively correlated only for men (r = .40, p = .001). For both men and women, relational victimization was positively correlated with attachment anxiety (rs > .28, ps < .01).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables.

Note: Correlations for men are presented below the diagonal and correlations for women are presented above the diagonal.

†p < .1. *p < .05. **p < .01.

Serial Mediation Analysis

The serial mediation of relational victimization and attachment anxiety on the associations between relational aggression and depressive symptoms was examined using Mplus (version 7.1). Due to the moderate sample size, bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was also used. Model fit was tested using Hu and Bentler’s (Reference Hu and Bentler1999) guidelines, including the cut-off scores of the comparative fit index (CFI) and/or Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) as greater than .95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than .06 and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) less than .08. The model included relational aggression as the predictor variable, mediators of relational victimization and attachment anxiety, and depressive symptoms as the outcome variable, with physical aggression and physical victimization as covariates. When testing the model including physical aggression as an added predictor and physical victimization as an added mediator, physical aggression and physical victimization were not significant in the model. The model was split by gender to distinguish effects between men and women. Attachment avoidance was also tested for mediation, but there were no significant indirect effects for attachment avoidance.

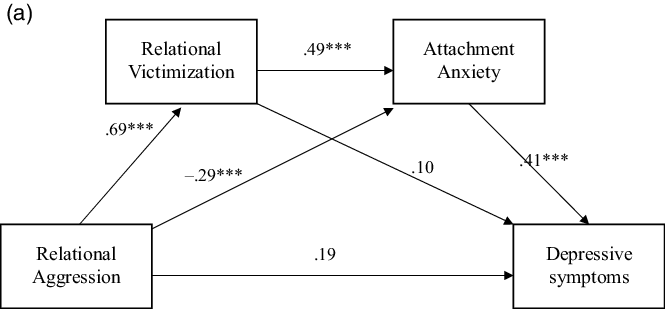

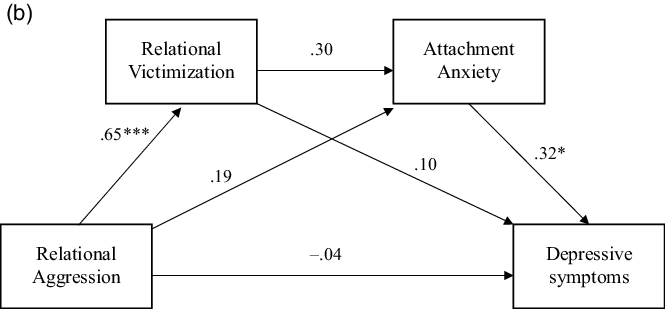

Results of the serial mediation analysis demonstrated that the total effect of relational aggression on depressive symptoms without the mediators included in the model was significant when including both men and women (β = .206, p < .01). For women, results of the serial mediation analysis demonstrated two significant indirect effects in the model (see Figure 1a). The indirect effect for the path from relational aggression to relational victimization to attachment anxiety to depressive symptoms was significant (β = .14, 95% CI [.06, .26]). Higher relational aggression was associated with higher relational victimization, which in turn was associated with higher attachment insecurity relating to higher depressive symptoms. The indirect effect for the path from relational aggression to attachment anxiety to depressive symptoms was also significant (β = −.12, 95% CI [−.03, −.25]). Higher relational aggression was associated with lower attachment anxiety, which in turn was associated with lower depressive symptoms. The indirect effect for the path from relational aggression to relational victimization to depressive symptoms was not significant (β = .07, 95% CI [−.16, .29]). When relational victimization and attachment anxiety were included in the model, the direct effect became nonsignificant (β =.19, ns). Therefore, the data were consistent with a model in which relational aggression predicts relational victimization, which then promotes feelings of attachment anxiety leading to depressive symptoms. For men, no significant indirect effects were found (see Figure 1b). Moderation of attachment insecurity and relational victimization on the link between relational aggression and depressive symptoms was also examined to ensure that the mediation only occurs in this link. No moderation effect was found for these factors for women and men.

Figure 1a. Mediation model of the relationship between relational aggression and depression with mediators of relational victimization and attachment anxiety for women.

Figure 1b. Mediation model of the relationship between relational aggression and depression with mediators of relational victimization and attachment anxiety for men.

Summary

The findings of the serial mediation analysis revealed the mediation of relational victimization and attachment anxiety only for females. The mediational paths were divergent in terms of their directions; that is, relational aggression was positively associated with relational victimization, but it was negatively linked with attachment anxiety. This suggests that relational aggression can be maladaptive as it is a risk of experiencing relational victimization, and it can be adaptive as it leads to less anxiety in close relationships. One way to disentangle these mixed findings is to take a person-centered approach to investigate subgroups of relationally aggressive females and males. Gender differences in this regard may explain why maladaptive and adaptive pathways from relational aggression to each mediator occurred only for females.

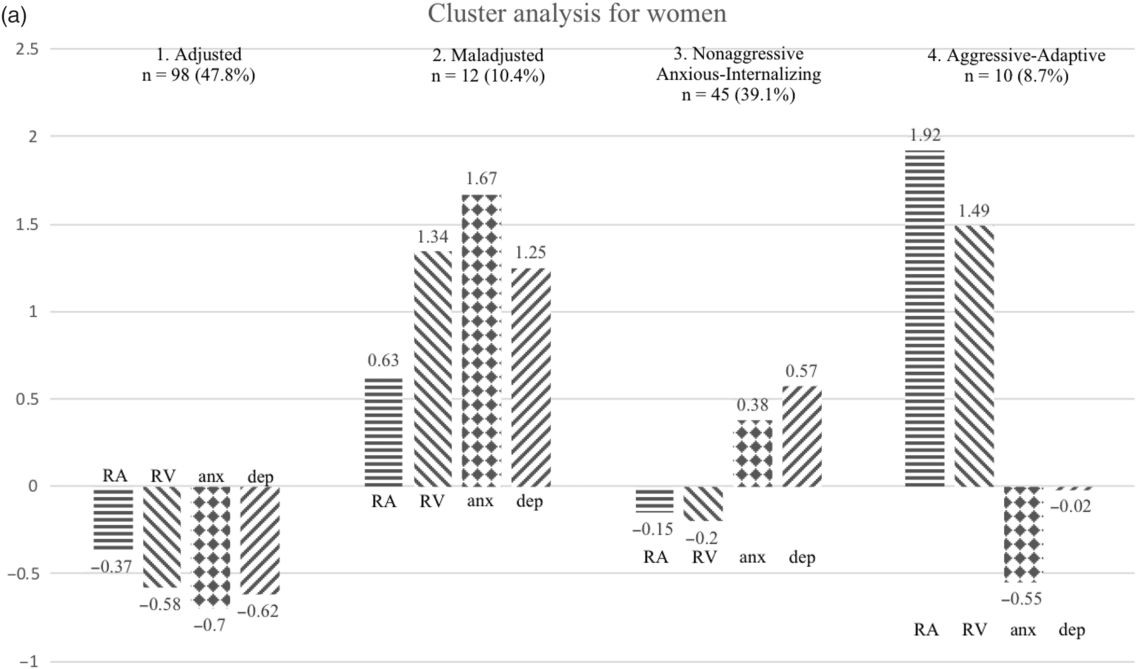

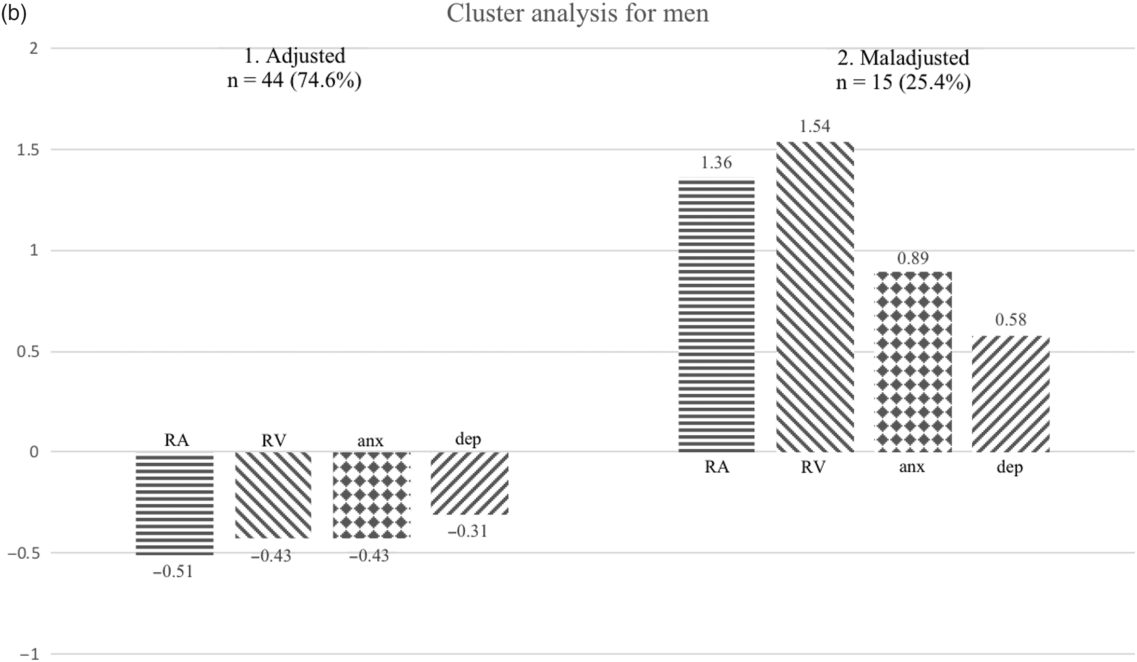

Supplementary Analysis

In order to help to explain gender differences in mediational paths, a cluster analysis was conducted, split by gender. Relational aggression, relational victimization, attachment anxiety, and depressive symptoms were examined. For women, four clusters were formed (adjusted, maladjusted, nonaggressive anxious-internalizing, and aggressive-adaptive; see Figure 2a). The adjusted cluster had low levels of all four variables, while the maladjusted cluster had high levels of all four variables. The nonaggressive anxious-internalizing cluster demonstrated slightly low levels of relational aggression and relational victimization but moderately high levels of attachment anxiety and depressive symptoms. The aggressive-adaptive cluster showed high levels of relational aggression and relational victimization, low levels of attachment anxiety, and slightly low level of depressive symptoms. However, for men, when using four clusters, all four clusters demonstrated two patterns of high levels of all four variables or low levels of all four variables (see Figure 2b). Therefore, for men, two clusters were formed (adjusted and maladjusted).

Figure 2a. Cluster analysis for women.

Figure 2b. Cluster analysis for men.

General Discussion

The present study is the first to examine the linkages among relational aggression, victimization, attachment, and depressive symptoms in Asia-Pacific Islands. The data from the pilot qualitative study revealed that relational aggression and victimization were commonly observed and possibly reciprocal within the close relationships, particularly for women. When emerging adults used relational aggression and/or experienced relational victimization, they reported that they often developed negative affect and emotion (i.e., being upset, anxious, sad and depressed). These initial findings are consistent with the data from the quantitative study showing that relational aggression was associated with greater levels of depressive symptoms only for women. In addition, relational victimization and attachment anxiety served as serial mediators only for women. Supplemental cluster analyses showing gender differences in terms of the subgroups of relationally aggressive emerging adults may help us interpret how and why some relationally aggressive women are more interpersonally vulnerable to depressive symptoms but display less attachment anxiety.

Supporting our hypothesis, the present study demonstrated that relational victimization and attachment insecurity mediated the link between relational aggression and depressive symptoms (only for women). In other words, relational aggression was associated with greater levels of relational victimization linking with more attachment anxiety, which in turn led to more depressive symptoms. Once both mediators were introduced in the model, the initial, direct association became null, suggesting full mediation. One possible mechanism for this full mediation is that relationally aggressive individuals tend to be an easy target of relational victimization, presumably due to their manipulative characteristics and behaviors, which then provides a negative socializing context for developing insecure attachment with their significant others. For example, individuals who experience relational victimization may feel overly anxious about their peers or partner and fail to form and maintain a healthy, supportive relationship. In turn, those who have an anxious attachment may develop a negative representation of the self in the close relationship, showing lower levels of self-esteem, self-worth and well-being, and then exhibit depressive thoughts and feelings leading to depressive symptoms (Groh et al., Reference Groh, Roisman, van Ijzendoorn, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Fearon2012). Given the cross-sectional, correlational nature of the present study, the conclusion about the causality of these developmental processes cannot be drawn. However, it is still plausible that relational victimization by significant others may make individuals, particularly women, feel more worried about their relationship or even betrayed, and thus they may become more cognitively and emotionally vulnerable to depression.

As hypothesized, the serial mediation effect of relational victimization and attachment insecurity was pronounced only for women. This finding is in line with the view of gender socialization that women place more emphasis on relationships than men; thus, they are more interpersonally vulnerable to negative experiences with significant others (Crick et al., Reference Crick, Ostrov, Kawabata, Flannery, Vazsonyi and Waldman2007; Rose & Rudolph, Reference Rose and Rudolph2006). It is possible then that women tend to find the use of relational aggression and experiences of relational victimization more stressful and elevate attachment anxiety toward others and depressive symptoms. One possible mechanism for this finding is that women are inclined to form relationships that are closer, more intimate and more exclusive (Rose & Rudolph, Reference Rose and Rudolph2006), and such very intimate or enmeshed relationships may increase anxiety and depressive symptoms when the quality of relationships turns negative. For example, women may be more likely to view the conflictual, difficult, or even relationally manipulative relationships as more burdensome than men.

One unexpected finding merits full discussion. That is, attachment anxiety mediated the association between relational aggression and depressive symptoms, while the contributions of relational victimization, physical aggression and physical victimization were controlled for; however, the direction of the mediation was not anticipated. In fact, the results showed that higher levels of relational aggression were linked with lower levels of attachment anxiety, which in turn contributed to fewer depressive symptoms. This finding is incongruent with our hypothesis that emerging adults who often use relational aggression are more insecurely attached to their significant others, and those who are highly anxious about relationships may fail to develop a positive internal working model, which reflects a difficulty in forming a secure and trustworthy relationship. One explanation for this discrepancy is that some relationally aggressive emerging adults may be developmentally adaptive, rather than maladaptive, to their peer group and relationship. The literature indicates that from an evolutionary perspective, some individuals have an ability to wisely utilize both prosocial and manipulative behaviors to maintain high social status and/or gain what they want (Heilbron & Prinstein, Reference Heilbron and Prinstein2008). Thus, some relationally aggressive women may be able to fit well in their peer group and strategically build seemingly harmonious relationships with their peers or partners. This view is in line with the findings of a supplemental cluster analysis showing that there was a subgroup of “aggressive-adaptive” relationally aggressive women who experienced high levels of relational victimization but exhibited low levels of attachment anxiety; however, such a subgroup of relationally aggressive men did not emerge. Given that Guam is a relationally oriented, collectivistic culture, people typically learn that maintaining harmony with others is an essential part of cultural socialization (Nakamura & Kawabata, Reference Nakamura and Kawabata2018). In such a culture, emerging adults who can develop social competence or interpersonal skills to connect with or attach to their peers and partners, while using relational manipulation tactically may be considered adaptive. A future study with a person-centered approach may reveal the complexity of the individual and gender differences in the processes of relational aggression, victimization and adjustment.

Limitations

One notable limitation is the generalizability and applicability of the findings to other populations (people outside Guam, other age groups). Due to the unbalanced gender distribution of the sample, the findings may be somewhat biased toward females’ perspectives of relational aggression and negative emotion. Statistical limitations, such as the small sample size for men and shared method bias require us to interpret the results with caution. Similar to other correlational studies, it is not possible to determine causal relationships among variables of interest in this study. The associations among predictors and mediators may be bidirectional. For example, relational victimization and attachment insecurity can increase relational aggression, which in turn relates to depressive symptoms. A future longitudinal study with multiple informants that examines transactional processes among relational factors is warranted.

Directions for Future Research

The present study revealed that relational aggression is associated with depressive symptoms via relational victimization and attachment insecurity for women; however, cultural factors that may influence this association and mediation remain unexamined. Guam is a culturally diverse environment in which local ethnic groups and the increasing number of immigrants from other Pacific islands and Asian countries cohabit. Due to the rapid rate of immigration, there are many incidents involving intergroup contact and discrimination among the majority and minority groups. It is possible that local youth may leave out immigrants due to their different ethnic background or skin color, and these nonlocal youth may perceive such an event as relational victimization or even ethnic discrimination. Given abundant evidence showing that many immigrants suffer from acculturation-linked stress and perceive ethnic discrimination (Pascoe & Smart Richman, Reference Pascoe and Smart Richman2009; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Chang, Kim, Clawson, Cleary, Hansen and Gomes2013), a future study that examines the role of culturally linked factors such as acculturation, discrimination and cross-ethnic peers on relational aggression is called for.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this article was supported by a CSR grant of College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, the University of Guam, awarded to Yoshito Kawabata.

Financial Support

none.