Law and public policy have long been seen as fundamentally related concepts. In Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville (Reference de Tocqueville and Bradley1835/1990, 280) made the observation that “[s]carcely any political question arises in America that is not resolved, sooner or later, into a judicial question.” In the 1940s, Lasswell and McDougal (Reference Lasswell and McDougal1943, 206) urged the integration of public policy concerns into legal education. Writing for their law school faculty colleagues, they made the bold statement that “[i]f legal education in the contemporary world is adequately to serve the needs of a free and productive commonwealth, it must be conscious, efficient, and systematic training for policy making.” The reverse also is true. Policy makers must understand law—and, in particular, the limits and possibilities of legal authority—to be effective in their role (Rosenbloom Reference Rosenbloom1987; Reference Rosenbloom2019).

This article examines the current state of graduate public policy education and finds that public policy programs do not sufficiently cover law in their curricula. We limited our analysis to Masters of Public Policy (MPP) degrees. We excluded public administration and similar programs. Despite some suggestion that MPP and Master of Public Administration (MPA) programs have converged (Ellwood Reference Ellwood2008), the degrees have distinct curricular focuses and prepare students for distinct types of public affairs employment (Hur and Hackbart Reference Hur and Hackbart2009; Kretzschmar Reference Kretzschmar2010). Whereas all public affairs professionals should have some understanding of law and legal process, we believe the need to recognize the policy-making role of law and courts is most acute in public policy programs.

We start with the empirical reality that courts are involved in the policy process (Kagan Reference Kagan, Miller and Barnes2004). We take no position on the normative debate over the proper scope of judicial authority with respect to open policy questions. Regardless of whether courts should play a role in policy making, they do. Their place in the public policy curriculum, therefore, should not be minimized. Public policy training cannot replace traditional legal education, but it can include an understanding of law and courts and their role in policy making.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF GRADUATE PUBLIC POLICY EDUCATION?

The Network of Schools of Public Policy, Affairs, and AdministrationFootnote 1 (NASPAA) is the accrediting body for graduate programs in public affairs. NASPAA’s standards play a major role in shaping the curriculum of various public service programs that fall under its auspices. NASPAA-accredited MPP programs are designed to prepare their graduates to take an active role in public policy. To meet these goals, we argue that graduate public policy programs must intentionally include courses on law and the role of courts in policy making.

We are not the first to call for a more intentional inclusion of law and legal issues in the public affairs curriculum, although much of the literature has been more focused on public administration programs than public policy programs. Hartmus (Reference Hartmus2008), Newbold (Reference Newbold2011), and Roberts (Reference Roberts2009) all argued for increased teaching of law in MPA programs. Their concern, however, was focused primarily on reducing liability risks rather than understanding policy making. We argue that teaching law and related issues in the public policy curriculum cannot be focused solely on avoiding personal and professional liability for wrongdoing. Students must be taught about law and the courts as tools for policy making.

We argue that teaching law and related issues in the public policy curriculum cannot be focused solely on avoiding personal and professional liability for wrongdoing. Students must be taught about law and the courts as tools for policy making.

ROLE OF LAW AND THE COURTS IN THE PUBLIC POLICY PROCESS

Law and public policy work in both conjunction and opposition. Although judges often are called to answer policy questions, they routinely decline to recognize their role in the political and policy process (Segal and Spaeth Reference Segal and Spaeth2002). Chief Justice Roberts, in his Senate confirmation hearing, insisted that judges do not make law, thereby rejecting any role in policy making for the judiciary. Other judges have made similar claims. This fails to capture the reality of what judges actually do. Bingham (Reference Bingham2010, 45), writing about judges in the United Kingdom, stated it succinctly: “[c]ases are brought raising novel questions, and the judges have to answer them. Their answers will often make law, whatever answer they give, one way or the other.” By making law, judges advance one policy outcome over another. This is as true for US judges as it is for British judges. When they act in this way, they are playing a role in the policy-making process.

Segal and Spaeth (2002, 2) stated that US history is “replete” with examples of judicial policy making. Reviewing the judiciary’s role in policy making between 1945 and 2004, Grossman and Swedlow (Reference Grossman and Swedlow2015) found that courts continued to play a role in shaping policy in the United States. Justices determine how and to what extent other officials can implement their desired policies. Courts influence the specific statutory language used to draft laws (Hinkle Reference Hinkle2015). Even one of the great critics of the judiciary’s power to make policy change acknowledged that it can happen under certain circumstances (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008). Legislators, bureaucrats, and policy advocates must be prepared for how the courts can shape policy outcomes and be ready to adapt to these changes.

Policy cases arrive at the courts in various ways. Litigation may remain confined to private action despite its broader implications for public policy. These cases can subsequently become supported by public-interest attorneys and the greater movement resources they can provide. In these cases, the effort to shape policy through the courts is more intentional. Both conservative and liberal groups in the United States advance their policy goals using litigation (Decker Reference Decker2016).

Courts and the rule of law also play a role in creating and limiting solutions to policy problems and in implementing those solutions. One way they do this is by defining rights (Stone Reference Stone2012). Rights enable actors in the democratic system to make certain demands of government and then to expect those demands to be met (Sheingold Reference Sheingold2004). Judicial definitions of rights may constrain available policy choices or require certain actions. This is illustrated by the Trump administration’s decision to strictly enforce immigration law, resulting in the forced separation of children from their parents. Family separation was allowed because a previous judicial decree outlining the limits of child detention restricted the policy options available to achieve the administration’s detention goals.

Lawsuits brought by individuals and organizations expand, contract, and explain the policy decisions made by legislators and bureaucrats (Kagan Reference Kagan2001). This results in significant unpredictability and delay in the US legal and policy systems. Even strict, prescriptive regulations remain subject to legal challenge and interpretation that can fundamentally alter legal obligations. This is seen in the protracted litigation surrounding the spotted owl in the Pacific Northwest. Swedlow (Reference Swedlow2003, 189) analyzed this issue and argued that judges were among “the most consequential policy makers.” The involvement of the courts extended this policy debate for more than a decade and upset the compromise created by Congress and the executive branch, which was designed to support multiple uses and address the multiple concerns at issue (Kagan Reference Kagan, Miller and Barnes2004).

The courts are integral to all stages of the policy process, and they serve to both advance and thwart policy goals. Public policy programs must provide students with a proper foundation in this literature and actual policy-making practice if they want to prepare them to be effective public servants.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Our goal was to understand whether and how law and courts are incorporated into public policy program curricula.Footnote 2 We explored the following two questions:

(1) What types of law are included in course offerings and how is that done?

(2) How is the judiciary included in course offerings?

The NASPAA database lists 40 schools that offer policy degrees, including both NASPAA-accredited and unaccredited programs. Although not all policy programs are included, NASPAA is the leading accreditation body for public affairs programs; we therefore restricted our analysis to the programs it recognizes. NASPAA also includes important characteristics about these programs, making it the best source of data for our analysis. We eliminated eight programs from consideration: six because they were located outside of the United States and our interest is limited to the US policy system and two because there was no program information available from the school’s website, making it impracticable to analyze those programs. Using a stratified random sample,Footnote 3 we chose 16 of the remaining 32 programs to evaluate.

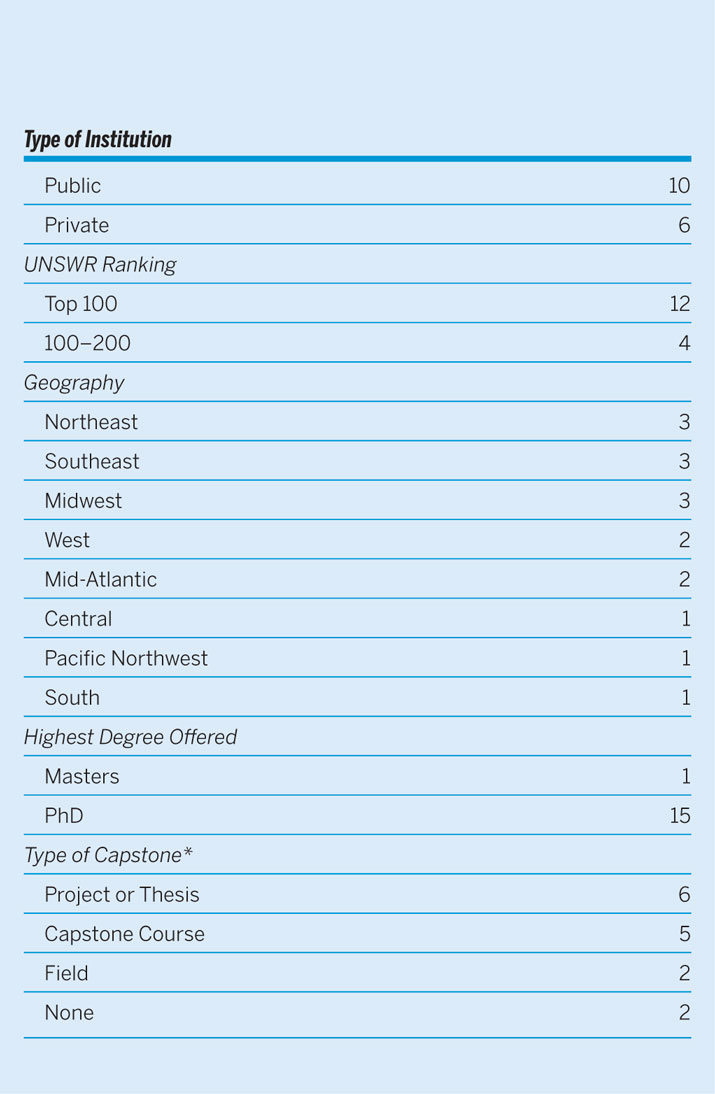

In addition to NASPAA data, we collected basic information about each program, including the US News and World Report (USNWR) ranking, the Carnegie Classification,Footnote 4 and whether the school is a public or private institution (table 1). We obtained program descriptions, structure, and curricula directly from university course catalogs and program websites. We also obtained course syllabi when they were available. We collected program data between July 2017 and July 2018.

Table 1 Description of Sample

Note: *One program offered multiple capstone options.

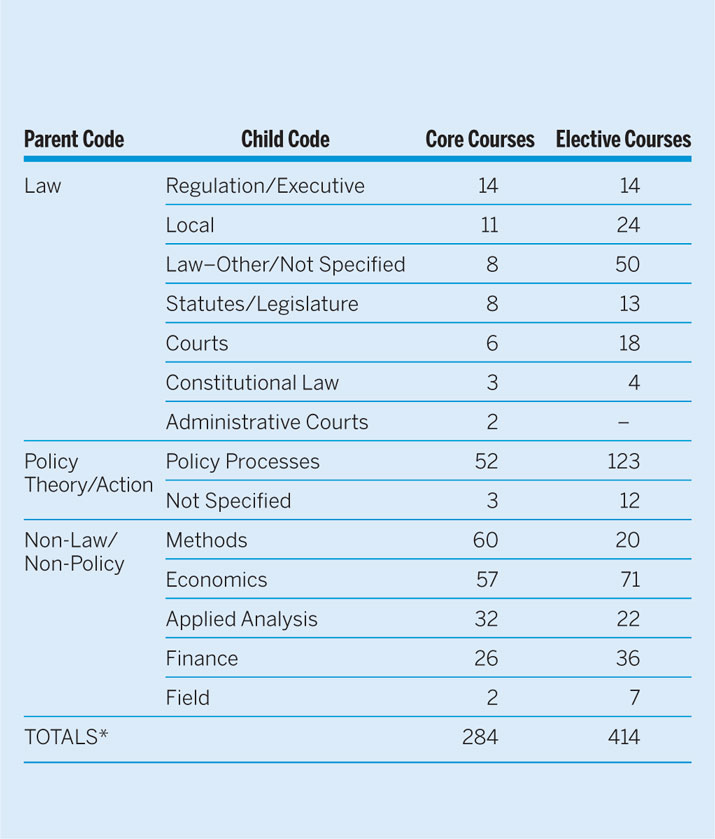

We coded courses using three parent codes: Law, Policy Theory/Action, and Non-Law/Non-Policy. The Law code included courses about law-making processes and structures related to courts, legislatures, executives, and regulatory agencies. We also used the Law code to identify courses that referenced specific issues in law (e.g., constitutional, criminal, and environmental), as well as those that referenced legal reasoning and legal theory. We used the Policy Theory/Action code to identify courses that focused on non-law-related policy areas, including those that referenced various policy-making theories, policy areas without any reference to law, and policy implementation. We also coded courses that focused on advocacy and lobbying. The Non-Law/Non-Policy code included courses related to methods and analysis, economics and finance, and field courses. The codes define mutually exclusive types of content. Individual courses, however, may include multiple types of content and have several different codes applied to them. For example, 25 courses were simultaneously coded as Applied Analysis (i.e., a child code of Non-Law/Non-Policy) and Policy Theory/Action.

In total, we coded 747 courses across all 16 programs. We coded 243 core courses across all 16 programs and an additional 504 electives across 13 programs. If a program had a list of elective courses from which students could choose to fulfill distribution requirements, we coded them. We did not code courses that were listed on the program’s website or flow sheets but were no longer listed in the course catalog. We also did not code electives that were available but not part of a distribution requirement.Footnote 5 These exclusions explain why three programs did not have electives included in the coding. This confined the analysis to those courses that a public policy student is most likely encounter. By including electives, we built on previous literature that was limited to core courses, providing a fuller picture of the possible topics MPP students are likely to encounter in their coursework (Hur and Hackbart Reference Hur and Hackbart2009; Kretzschmar Reference Kretzschmar2010).

After coding, we reviewed the courses in each code individually to ascertain the way in which law was or was not incorporated into them. We were interested in the number and specific content of courses that referenced the courts either directly or indirectly. We also evaluated program characteristics to determine whether any patterns could be related to them. We did this by comparing codes across program characteristics (e.g., Con Law code by USNWR ranking) to determine any related variations.

LAW AND PUBLIC POLICY: WHAT ARE WE TEACHING?

Most core courses focused on (in order of frequency) research methods and analysis; economics; and theory, concepts, or history (table 2). We found no meaningful differences in the relative emphasis of these based on rank or other program characteristics. Only one program, at a public university that emphasized policy and management courses in its core curriculum, deviated from this general pattern.

Table 2 Frequency of Selected Codes in Courses†

Notes: †Only those codes relevant to this analysis are presented here. *Totals include courses that are coded across multiple codes.

Only one program had core courses that explicitly recognize courts as policy actors. Five other programs included courses related to the judiciary or case law in their core offerings. One program offered one course that referenced both constitutional and administrative law, as well as courts broadly. It was not, however, a public policy course. Instead, it focused on the legal justifications for administrative work. Executive agencies were the most common policy actor in the courses we reviewed, with legislatures as a distant second.

The majority of elective courses were focused topically on either a policy domain (e.g., branch of government), scholarly area of interest (e.g., gender studies), or specific skills in either methodology or the policy process (e.g., lobbying). Elective courses were oriented mainly around non-court-related policy processes or economics. The significant presence of economics courses in both core and elective courses reveals a potentially outsized role of economics training in many policy programs compared to other ways of understanding public policy (figure 1).

Figure 1 Percentage of Courses Coded in Each Category

In general, law-related courses were included only infrequently in electives relative to other topics. When courts are specified, they most often focus on a particular area of law (e.g., criminal or environmental) or legal theory rather than the broad role of courts in public policy. Only three programs offered a course that incorporated constitutional law as an elective. The focus here, however, was not on the role of constitutional law in policy or as a tool for policy change.

What Types of Law Are Included in Course Offerings and How?

Law is not included at all in many courses. We found only one course, which was more public administration than public policy, in which legal reasoning was an explicit learning objective. When case law appeared in core course offerings, it was mostly constitutional law; four courses across three programs included constitutional law. Two of these courses focused on constitutional issues related to budgets generally or to financing (specifically in education). The other two focused on developing a conceptual understanding of the Constitution’s role in the development of public administration processes.

The only types of law included in elective courses were focused mostly on statutes and regulations, generally in the context of a specific policy area or matter of law (e.g., education). Incorporation of statutory law almost always focused on Congress. We found two exceptions to this federal focus. Both were in programs at public universities explicitly oriented around law and policy in their respective states. Courses in which regulatory law was incorporated or focused on did not always specify whether they were oriented around federal or state law. All of the courses, however, seemed to explain the existing law rather than showing how law and the judiciary can be used as a policy tool to change law. This is an important distinction.

When courts were included, it was generally to discuss the decisions made in federal appellate courts. Only two core courses explicitly included administrative courts. As mentioned previously, one course focused on the legal justifications for public administration, the other on unspecified “problems and issues” in administrative law. When courts were included in electives, they were frequently framed in terms of either the current state of law in a policy area or on court management and administration. Courts as policy actors were largely ignored.

There were few references to local law-making structures or processes. When we did find them, they tended to focus directly or indirectly on community or economic development. Most courses that included local law were focused explicitly on urban areas or metropolitan regions. There was a distinct lack of explicit attention to rural places in the programs studied. The courts also were conspicuously absent despite the well-recognized influence of judicial decisions on local policy making (Briffault Reference Briffault1990; Macchiarola Reference Macchiarola1971).

In general, few courses incorporated constitutional law, case law, or even administrative law decisions as part of the policy process. Most public policy programs conceive of law mainly in terms of statutes or regulations and mostly at the federal level. Large swaths of the legal landscape appear absent from program curricula—most glaringly, the role of the judiciary in changing policy at all levels of government.

How Is the Role of the Judiciary Included in Course Offerings?

Courts as policy actors were not explicitly included in any of the courses surveyed. Courts were either indirectly referenced or the course description was broad enough to include the judiciary, depending on instructor preferences. One school made indirect references to the judiciary in four core courses: theory/conceptually oriented courses or those on specific policy topics. In other schools, judicial systems, structures, and processes may be incorporated into special topics courses, again, depending on instructor preferences. This pattern held for elective courses as well. Courts were not explicitly framed as policy makers in any of the courses surveyed.

Courts were not explicitly framed as policy makers in any of the courses surveyed.

CONCLUSIONS, CAVEATS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Our analysis used course descriptions as a proxy for course content. We acknowledge that content can vary, sometimes significantly, from course descriptions. Course descriptions, however, do provide evidence about a program’s intended learning goals and objectives. The types of courses taught—or not taught—as well as their descriptions reveal the body of knowledge and skills that programs believe their graduates should master. While it is true that the judiciary as a policy actor or litigation as a policy strategy may be included in actual course content, the lack of specific courses and the absence of explicit integration of the judiciary into existing policy courses suggest that policy programs are not intentional about incorporating law or judicial policy making into their curricula.

To correct this gap, we suggest that policy programs take a broader approach to law than is currently covered. The courses in our sample do not focus on the courts as policy makers. Some reference law but almost always in the context of the constitutional limits on administrative authority or avoiding liability. Some courses cover specific types of law; however, these are not focused on the intersection of law, courts, and policy making. They teach students what the law is but not how to use law and the courts to advance or defend policy goals. The current emphasis leaves policy students ill-prepared for the actual world of policy making, which often involves strategic litigation.

The current emphasis leaves policy students ill-prepared for the actual world of policy making, which often involves strategic litigation.

Graduate programs can take several approaches to achieve this broader focus. Core program requirements could be amended to add a specific course on judicial policy making, including strategic litigation or the role of amicus curiae briefs in policy-relevant lawsuits. Programs could add specific legal electives to the curriculum that go beyond simply teaching the current boundaries of the law. Courses could focus instead on the development of an area of law and how that legal development shapes and constrains policy choices made by others in the system.

This broader approach also should address the omission of local policy making that we found. Because between 10% and 30% of MPP graduates work in local government, this absence is problematic (Hur and Hackbart Reference Hur and Hackbart2009). Programs also should consider including international law. While a focus on US law and policy makes sense, the law and policy environment is becoming increasingly globalized, making international law more important today.

Finally, the NASPAA accreditation guidelines should include specific reference to judicial policy making. These guidelines strongly influence what is taught in graduate programs and, by extension, what is not. If NASPAA required a more intentional, direct inclusion of judicial policy making in its core competencies, schools would adapt their programs to meet this standard. Programs then would provide students with the full array of policy tools available and, hopefully, lead to more informed policy making.

We also acknowledge the often zero-sum reality of curriculum development. For every course on judicial policy making added to the requirements, another may need to be eliminated to accommodate student schedules. We think that replacement is well worth the loss of other required courses. In our sample, for example, we noted an overrepresentation of economics courses; on average, two economics courses are required in core courses. Although an understanding of economics remains essential to public policy, economic analysis is not the only way to rigorously study and shape public policy. Moreover, to properly conduct an economic analysis of policy making, students must be aware of all possible policy-making venues and institutions. We suggest that programs scale back their economics coursework to incorporate judicial policy making. By continuing to ignore the courts’ role in policy making, programs are depriving students of information necessary for their future careers.