Patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) have impairments in the self-conscious emotions that guide social behavior (Sturm et al., Reference Sturm, Rosen, Allison, Miller and Levenson2006, Reference Sturm, Ascher, Miller and Levenson2008). Among early-onset dementias, bvFTD is second only to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common cause of dementia and one frequently confused with bvFTD. The absence of self-conscious emotions can help in distinguishing bvFTD from AD and other conditions on initial presentation. Patients with bvFTD, however, lack emotional insight (Mendez and Shapira, Reference Mendez and Shapira2011), and their self-reports of emotions may not be reliable. This pilot study investigates the value of caregiver ratings of self-conscious emotions vs. a self-report scale of ease of embarrassment in patients with bvFTD compared to those with AD. It further validates these assessments with skin conduction responses (SCRs) to an embarrassing event.

Methods

The study included seven patients who met International Consensus Criteria for clinically probable behavioral variant FTD (Rascovsky et al., Reference Rascovsky2011), seven who met National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for clinically probably AD (McKhann et al., Reference Mckhann2011), and seven healthy comparison (HC) volunteers. 1.) Caregivers rated the patient’s self-awareness of 10 self-conscious emotions such as embarrassment and guilt on a scale of 0 to 2 (Mendez et al., Reference Mendez, Akhlaghipour and Jimenez2021). 2.) Participants completed the 36-item Embarrassability (EMB) Scale in which they were asked to imagine themselves in embarrassing situations and record their own level of embarrassment or self-consciousness on a 5-point Likert scale (Mendez et al., Reference Mendez, Yerstein and Jimenez2020). 3.) Participants were seated in a quiet room three feet from a monitor and underwent continuous SCR recordings (Biopac MP150; GSR 100C; AcqKnowledge v4.1 software; 5 μS/V, low-pass filter 1Hz, no high-pass filter, 31.25 Hz sampling rate). They were first recorded during a 2-minute participation in research tasks requiring stimulus discrimination, and then, after a short delay, they were unexpectedly presented with the 2-minute videos of themselves, which they viewed in the presence of an audience of three researchers.

Results

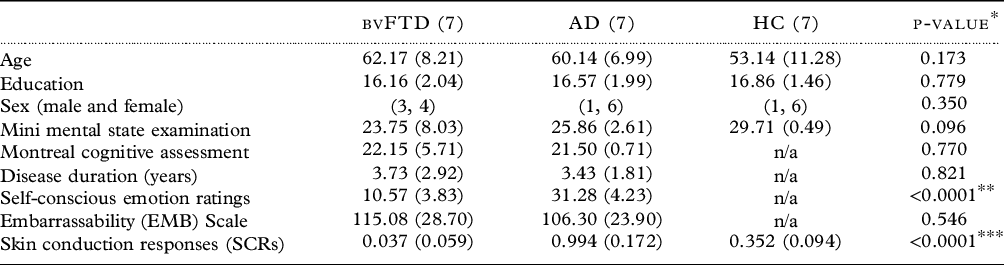

The dementia groups significantly differed on self-conscious emotion ratings and on the SCR during self-viewing, with the participants with bvFTD most impaired on both (See Table 1). There were no significant differences between the bvFTD and the AD groups on the EMB scale, nor between all three groups in reporting “self-consciousness” during self-viewing (4 bvFTD, 5 AD, and 5 HC). Partial Pearson’s correlation, which controlled for dementia group membership, between the self-conscious emotion ratings and SCR was 0.589, significant at the p < 0.05 level (two-tailed). There was no significant correlation between the EMB scale and either the self-conscious emotion ratings or the SCR.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics: Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and healthy comparison (HC) groups

Means and standard deviations except for sex.

* Three-group one-way ANOVAs except χ2 for sex; two-group t-tests.

** t = 9.602, df 12.

*** F = 119.218, df 2,18, Tukey’s HDS post hoc bvFTD vs AD and AD vs. HC both <0.0001; bvFTD vs HC <0.0003.

In this pilot study, participants with bvFTD, compared to those with AD, had decreased self-conscious emotions on caregiver ratings, and they had confirmatory impairment of SCR, a physiological index of emotion. These two measures significantly correlated even after controlling for dementia diagnosis. Yet, their self-reports of embarrassment were not different than those for the AD patients, emphasizing the need to avoid self-reports and the necessity for caregiver ratings, as bvFTD patients lack emotional insight and self-awareness (Mendez and Shapira, Reference Mendez and Shapira2011). The finding of this preliminary study should lead to a larger investigation of the value of a screen for self-conscious emotions screen when first evaluating patients for possible bvFTD.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author roles

MFM analyzed and wrote paper; EEJ organized and supervised the research.