A major challenge facing health systems in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) is how to mitigate common mental disorders in settings where health systems are not adequately resourced to provide psychological services, including insufficient numbers of mental health specialists. The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development pointed to the gaps that exist between the need for mental health services and the capacity of LMICs to provide assistance (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana, Bolton, Chisholm, Collins, Cooper, Eaton, Herrman, Herzallah, Huang, Jordans, Kleinman, Medina-Mora, Morgan, Niaz, Omigbodun, Sondorp, Pfaltz, Ruttenberg, Schick, Schnyder, van Ommeren, Ventevogel, Weissbecker, Weitz, Wiedemann, Whitney and UnUtzer2018) which is supported by much evidence (Moitra et al., Reference Moitra, Santomauro, Collins, Vos, Whiteford, Saxena and Ferrari2022). This situation has led to task-sharing initiatives, where non-specialists receive brief trainings in psychosocial programmes to deliver mental health services in LMICs. Meta-analysis indicates that it can achieve a moderate effect size in alleviating common mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression (Singla et al., Reference Singla, Kohrt, Murray, Anand, Chorpita and Patel2017). One widely used approach involves Problem Management Plus (PM + ). PM + was developed by the World Health Organization as a brief, transdiagnostic intervention to reduce common psychological disorders in people affected by adversity (WHO, 2016). This intervention teaches skills in arousal reduction, problem management, behavioural activation and accessing social support across five sessions (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015). PM + delivered in individual (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson, Khan, Azeemi, Akhtar, Nazir, Chiumento, Sijbrandij, Wang, Farooq and van Ommeren2016; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Schafer, Dawson, Anjuri, Mulili, Ndogoni, Koyiet, Sijbrandij, Ulate, Harper Shehadeh, Hadzi-Pavlovic and van Ommeren2017) and group (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Khan, Hamdani, Chiumento, Akhtar, Nazir, Nisar, Masood, Din, Khan, Bryant, Dawson, Sijbrandij, Wang and van Ommeren2019; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Sangraula, Turner, Wang, Shrestha, Ghimire, Van't Hof, Bryant, Dawson, Marahatta, Luitel and van Ommeren2021; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bawaneh, Awwad, Al-Hayek, Giardinelli, Whitney, Jordans, Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Ventevogel, Dawson and Akhtar2022) formats has been shown to be effective in reducing common mental disorders.

The evidence for PM + is limited, however, by relatively short-term follow-up assessments, typically with only three months follow-ups (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson, Khan, Azeemi, Akhtar, Nazir, Chiumento, Sijbrandij, Wang, Farooq and van Ommeren2016, Reference Rahman, Khan, Hamdani, Chiumento, Akhtar, Nazir, Nisar, Masood, Din, Khan, Bryant, Dawson, Sijbrandij, Wang and van Ommeren2019; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Schafer, Dawson, Anjuri, Mulili, Ndogoni, Koyiet, Sijbrandij, Ulate, Harper Shehadeh, Hadzi-Pavlovic and van Ommeren2017; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Sangraula, Turner, Wang, Shrestha, Ghimire, Van't Hof, Bryant, Dawson, Marahatta, Luitel and van Ommeren2021). This seriously limits our understanding of the longer-term effects of brief psychological interventions in LMIC. Task-sharing interventions are typically implemented among populations exposed to ongoing stressors, including poverty, overcrowding, violence and other adversities, which is likely to increase psychological difficulties after completion of brief psychological interventions (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019). To address the lack of longer-term follow-up assessments in brief, task-sharing interventions, this study reports on a 12-month follow-up of a controlled trial of group PM + (gPM + ) that was conducted with Syrian refugees residing in a camp in Jordan (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Giardinelli, Bawaneh, Awwad, Naser, Whitney, Jordans, Sijbrandij and Bryant2020) as part of multi-site research programme on scalable psychological interventions for Syrian refugees STRENGTHS Consortium (Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Acarturk, Bird, Bryant, Burchert, Carswell, de Jong, Dinesen, Dawson, El Chammay, van Ittersum, Jordans, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Miller, Morina, Park, Roberts, van Son and Cuijpers2017). This trial aimed to assess the extent to which gPM + could reduce anxiety, depression, personally identified problems, unhelpful parenting behaviours and refugees' children psychological distress. Prior reporting on this study found that at the 3-month follow-up, refugees who received gPM + achieved greater reductions in the primary outcome of depression, as well as personally identified problems and inconsistent disciplinary parenting, relative to those who received enhanced usual care (EUC) (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bawaneh, Awwad, Al-Hayek, Giardinelli, Whitney, Jordans, Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Ventevogel, Dawson and Akhtar2022). We hypothesised that refugees receiving PM + would still have greater reductions in depression, personally identified problems and inconsistent disciplinary parenting at 12-months relative to those receiving EUC.

Methods

Trial design

This two-arm, single-blind randomised controlled trial was conducted in Azraq Refugee Camp in Jordan in partnership with the International Medical Corps (IMC) Jordan. The project was prospectively registered (Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, no. 12619001386123) and the trial protocol is available in online Supplementary Information (S1 Protocol) and published (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Giardinelli, Bawaneh, Awwad, Naser, Whitney, Jordans, Sijbrandij and Bryant2020). This study is reported as per the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline (online Supplementary Information S2 Checklist).

Participants

The participants were refugees residing in Azraq Camp who were: (a) aged ⩾ 18 years, (b) Arabic-speaking, (c) scored ⩾16 on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek, Normand, Walters and Zaslavsky2002), (d) scored ⩾17 on the WHO 12 item Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0; WHODAS Group, 2000), and (e) had a child or dependent living in the household aged 10–16 years. The latter criterion was included to measure the secondary effects of gPM + on the mental health of participants' children. The K10 is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses psychological distress, with a range of 10–50, and the cut-off of 16 has been successfully used in refugee populations to identify distress (Shawyer et al., Reference Shawyer, Enticott, Block, Cheng and Meadows2017). The WHODAS 2.0 is a 12-item questionnaire that assesses general functioning, with a possible total score of 48, and the cut-off followed prior trials of gPM + to ensure that participants were experiencing impaired function (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Khan, Hamdani, Chiumento, Akhtar, Nazir, Nisar, Masood, Din, Khan, Bryant, Dawson, Sijbrandij, Wang and van Ommeren2019). Participants were excluded if there was presence of: (a) significant cognitive or neurological impairment, (b) acute medical conditions, (c) severe mental disorders (e.g. psychotic or substance-abuse disorders) or (d) acute risk of suicide. Participants were recruited through door-to-door screening of consecutive caravans in the camp (one adult per caravan was invited). Participants provided informed consent for both the screening and, for those who screened positive, the trial. Caregivers also provided written consent for participation for one of their children to be assessed, from whom verbal assent was obtained.

Participants were randomly assigned on a 1:1 ratio to gPM + or EUC. Randomisation was conducted by staff at UNSW using software that generated random number sequences. Allocation concealment was maintained by assigning treatment conditions in sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes that informed the trial co-ordinator in Jordan on assignment to gPM + or EUC. The assessors were blinded to group allocation.

The gPM + treatment is described in more detail elsewhere (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015) (see online Supplementary Information Table 1). Across five weekly 2 h group sessions (6–12 people in gender-specific groups) participants were taught psychoeducation, stress management focusing on breathing retraining, problem management, behavioural activation and accessing social support. Each group was led by two facilitators who had a bachelor's degree in social science or related discipline, spoke Arabic, but had limited to no prior experience in psychosocial programmes. Facilitators each received eight days of training that included group facilitation skills and gPM + delivery, followed by supervision during two practice cycles of gPM + . EUC comprised a 15-min visit to the participant's caravan by IMC staff who provided them with specific referral information of psychosocial services available in the camp that were appropriate for the types of problems identified in their baseline assessment (e.g. mental health, vocational training).

A local Study Safety Committee that comprised three Jordanian health professionals was established to monitor any adverse events that occurred during the trial. All adverse events were reported by assessors or gPM + facilitators to the committee, who referred to local services.

Outcomes

All outcome measures underwent cultural adaptation and where necessary were translated and back-translated into Arabic. Full details of the adaptation process are published elsewhere (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Giardinelli, Bawaneh, Awwad, Naser, Whitney, Jordans, Sijbrandij and Bryant2020, Reference Akhtar, Heidrun Engels, Bawaneh, Bird, Bryant, Cuijpers, Hansen, Al-Hayek, Ilkkursun, Kurt, Sijbrandij, Underhill and Acarturk2021b). The primary outcomes were total scores on the depression and anxiety scales of the 25-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25). The HSCL-25 has been validated in Arabic contexts, where recommended cut-offs for probable caseness of anxiety and depression relative to structured clinical interview is 2.0 and 2.1, respectively (Mahfoud et al., Reference Mahfoud, Kobeissi, Peters, Araya, Ghantous and Khoury2013). The internal consistency of the HSCL-25 in the current sample was robust for the anxiety (0.79) and depression (0.84) scales. The secondary outcomes assessed disability with the WHODAS 2.0 because it is important to gauge functional outcomes as distinct from psychopathology outcomes; posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms with the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Blevins et al., Reference Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte and Domino2015) because Syrian refugees have elevated rates of PTSD (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Guajardo, Sahle, Renzaho and Slewa-Younan2022); personally identified problems with the Psychological Outcome Profiles (PSYCHLOPS; Ashworth, Reference Ashworth, Shepherd, Christey, Matthews, Wright, Parmentier, Robinson and Godfrey2004) to obtain an index of problems that are not captured by standardised measures; grief with the PG-13 (Prigerson et al., Reference Prigerson, Horowitz, Jacobs, Parkes, Aslan, Goodkin, Raphael, Marwit, Wortman, Neimeyer, Bonanno, Block, Kissane, Boelen, Maercker, Litz, Johnson, First and Maciejewski2009) because of the high rates of prolonged grief among Syrian refugees (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bawaneh, Giardinelli, Awwad, Al-Hayek and Akhtar2021); prodromal psychosis symptoms with the Prodromal Questionnaire-16 (PQ-B; Loewy et al., Reference Loewy, Pearson, Vinogradov, Bearden and Cannon2011) because refugees are at heightened risk for psychosis (Brandt et al., Reference Brandt, Henssler, Muller, Wall, Gabel and Heinz2019); parenting skills with the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire-42 (APQ; Maguin et al., Reference Maguin, Nochajski, De Wit and Safyer2016) that measures parental involvement, poor supervision, positive parenting, inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment to determine if gPM + impacted refugee's parenting; and refugees' children's mental health with the Paediatric Symptom Checklist (Jellinek et al., Reference Jellinek, Murphy, Little, Pagano, Comer and Kelleher1999) that comprises internalising, externalising and attentional problem subscales. At baseline and 12 months, participants completed an adapted 27-item Traumatic Events Checklists (Shoeb et al., Reference Shoeb, Weinstein and Mollica2007) to measure exposure to traumatic events and a 17-item Post-Migration Living Difficulties checklist (Silove et al., Reference Silove, Sinnerbrink, Field, Manicavasagar and Steel1997) to assess post-migration challenges.

Assessments were administered by Arabic-speaking Jordanians, who received four days of training in the assessment battery and psychological first aid. Assessors administered each assessment verbally and entered responses on portable tablets. All participants were given a gift worth 3 JOD ($US4) to reimburse their time for completing the post-intervention, 3-month, and 12-month assessments but were not reimbursed for participants in the gPM + sessions.

Statistical analyses

The initial power analysis estimated that a medium effect size (d = 0.4) for gPM + could be achieved at the 3-month primary follow-up through a sample size of 133 participants per group (power = 0.90, a = 0.05, two-sided); the trial estimated that there would be 35% attrition at 3 months follow-up, and so the trial included 410 participants (205 in gPM + and 205 in EUC).

Results

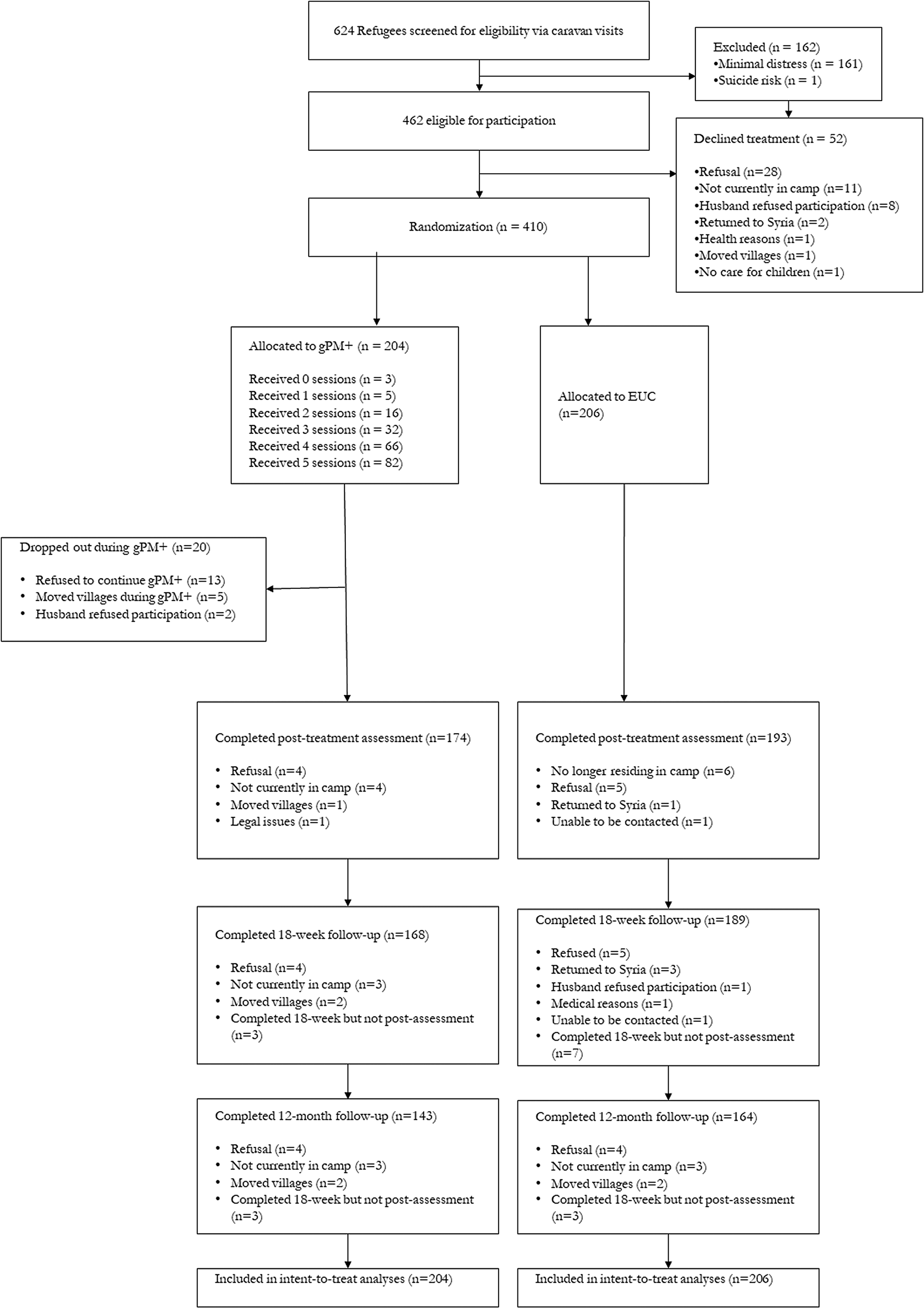

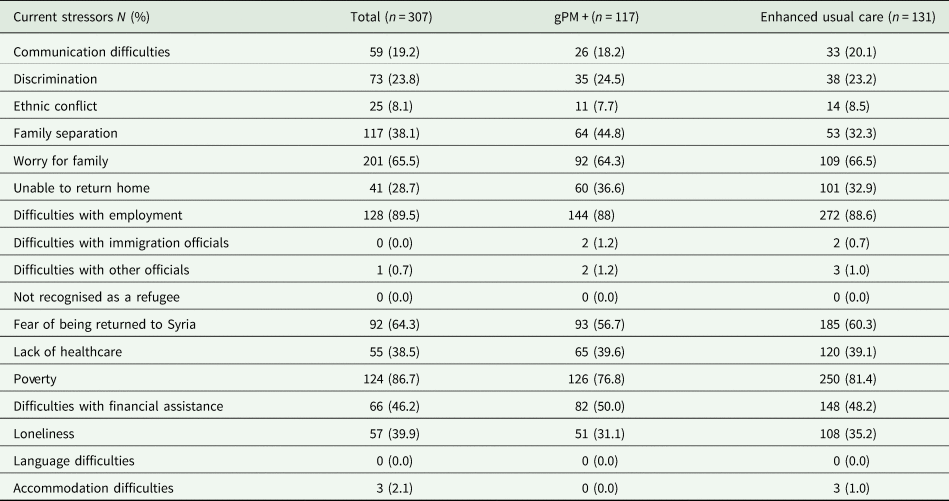

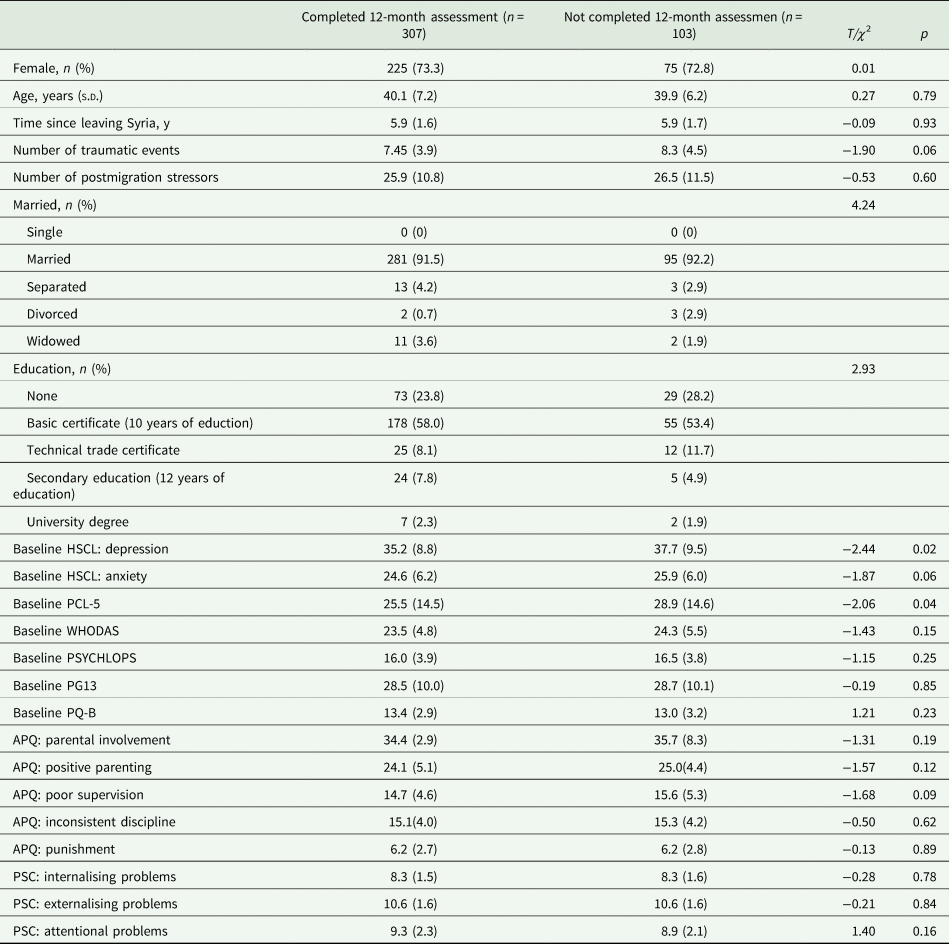

Participants were enroled between 14 October 2019 and 2 March 2020, and the final 12-month assessments were conducted on 31 May 2021. There were 1377 caravans approached during screen, 624 refugees agreed to be screened, of which 462 met entry criteria and 410 proceeded to randomisation (204 randomised to gPM + and 206 to EUC). Full details of the participants are reported in the prior report of the study (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bawaneh, Awwad, Al-Hayek, Giardinelli, Whitney, Jordans, Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Ventevogel, Dawson and Akhtar2022) and reported in online Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. The mean age of participants was 40.03 years (s.d. 6.95), most were female (70.2% females) and the mean time since leaving their home in Syria was 5.89 years (s.d. 1.67; range: 1–9 years). The most common living difficulties at 12 months were poverty (86.7%), difficulties with employment (89.5%), worry about family (65.5%) and fear of being returned to Syria (64.3%) (see Table 1). The demographic characteristics were not significantly different between the two treatment arms. The 12-month assessment was conducted for 307 participants (74.9%) participants. There were more participants retained in the EUC condition (164, 79.6%) than gPM + (143, 70.1%), χ 2 = 4.9, p = 0.03. Participants who did and did not complete the 12-month assessment did not differ on any baseline characteristics (with a Bonferroni-adjusted ɑ = 0.002), however those who dropped out had marginally higher depression and PTSD scores than those who were retained (Table 2). The flowchart of participant recruitment and retention is reported in Fig. 1. Although the number of postmigration stressors reported at baseline (26.0 ± 11.0) was higher than reported at 12 months (17.2 ± 7.7), the ongoing stressors were still at a high level. No adverse events were attributable to the interventions or the trial.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of progress through phases of a randomised trial comparing the group problem management plus intervention v. EUC in Syrian refugees in Azraq Refugee Camp, Jordan.

Table 1. Frequencies and percentages of rates of post-migration living difficulties at 12 months

Table 2. Participant characteristics

gPM + , Group Problem Management Plus; EUC, Enhanced usual care; HSCL, Hopkins Symptom Checklist (depression subscale score range: 10–40; anxiety subscale score range: 15–60; higher scores indicate elevated anxiety or depression); WHODAS, WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (total score range: 0–48; higher scores indicate more severe impairment); PCL-5, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (total score range: 0–80; higher scores indicate more severe PTSD severity); PSYCHLOPS, Psychological Outcomes Profiles (total score range: 0–20; higher scores indicate poorer outcome); PG-13, Prolonged Grief Disorder 13 (total score range: 11–57; higher scores indicate poorer outcome); PQ, Prodromal Questionnaire (total score range: 0–64; higher scores indicate poorer outcome). Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Parental Involvement subscale score range: 10–50; Positive Parent subscale score range: 6–30; Supervision subscale score range 10–50; Discipline subscale score range 6–30; Punishment subscale score range 3–15; higher scores indicate elevated parental involvement, positive parenting, supervision, discipline and punishment). Paediatric Symptom Checklist is child's self-report (PSC; Attention Problems subscale score range: 0–10; Internalising subscale score range: 0–10; Externalising subscale score range: 0–14).

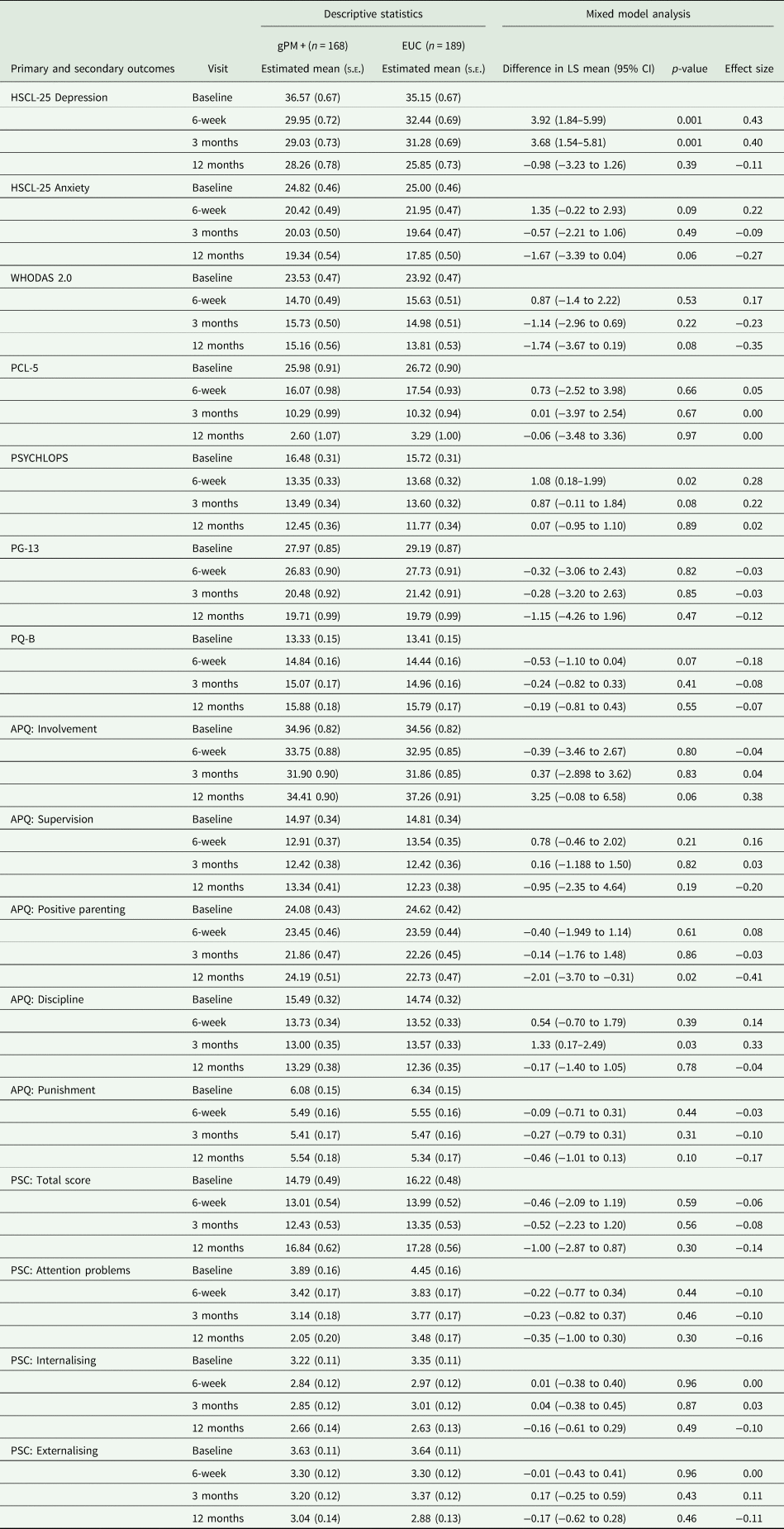

Regarding primary outcomes, at the 12-month assessment there were no significant differences between gPM + and EUC on either HSCL-Depression (adjusted mean difference −1.0, 95% CI −3.2 to 1.3; p = 0.39; effect size, 0.11) or HSCL-Anxiety (adjusted mean difference −1.7, 95% CI −4.8 to −1.3; p = 0.06; effect size, 0.27) scores (Table 3). It should be noted that although there were no significant differences between these conditions, participants in EUC tended to have greater reductions at 12 months relative to gPM + , and especially in terms of anxiety. There were no differences between the two treatment arms at 12-months on any of the secondary outcomes, with the exception that participants in gPM + reported more improved positive parenting relative to those in EUC (adjusted mean difference −2.0, 95% CI −3.7 to −0.3; p = 0.02; effect size, 0.41) (Table 3).

Table 3. Summary statistics and results from mixed model analysis of primary and secondary outcomes

EUC, Enhanced usual care; LS, Least Square; HSCL, Hopkins Symptom Checklist (depression subscale score range: 10–40; anxiety subscale score range: 15–60; higher scores indicate elevated anxiety or depression); PQ-B, Brief Prodromal Questionnaire; WHODAS 2.0, WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (total score range: 0–48; higher scores indicate more severe impairment); PCL-5, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (total score range: 0–80; higher scores indicate more severe PTSD severity); PSYCHLOPS, Psychological Outcomes Profiles (total score range: 0–20; higher scores indicate poorer outcome); PG-13, Prolonged Grief Disorder 13 (total score range: 11–57; higher scores indicate poorer outcome); PQ, Prodromal Questionnaire; (total score range: 0–64; higher scores indicate poorer outcome); APQ, Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Parental Involvement subscale score range: 10–50; Positive Parent subscale score range (total score range : 6–30; higher scores indicate poorer outcome); Supervision subscale score range 10–50; Discipline subscale score range 6–30; Punishment subscale score range 3–15; higher scores indicate elevated parental involvement, positive parenting, supervision, discipline and punishment). Paediatric Symptom Checklist is child's self-report (PSC; Attention Problems subscale score range: 0–10; Internalising subscale score range: 0–10; Externalising subscale score range: 0–14). Effect size was calculated by the difference in least square means between intervention and EUC from mixed model divided by the pooled standard deviation.

Supplementary analyses indicated that (a) focused only on participants who completed the 12-month assessment, and (b) controlled for ongoing stressors and exposure to traumatic events in the past 12 months also found no differences between treatment conditions (see online Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), except that after controlling for stressors and traumatic events gPM + resulted in greater changes in positive parenting relative to EUC (adjusted mean difference −2.44, 95% CI −4.53 to −0.36; p = 0.02; effect size, −0.50). We also conducted a secondary analysis that was not prescribed in the analysis plan to determine the proportion of participants whose depression and anxiety deteriorated between the 3- and 12-months assessments. Following previous methods of determining worsening of symptoms (Guidi et al., Reference Guidi, Brakemeier, Bockting, Cosci, Cuijpers, Jarrett, Linden, Marks, Peretti, Rafanelli, Rief, Schneider, Schnyder, Sensky, Tomba, Vazquez, Vieta, Zipfel, Wright and Fava2018), we calculated worsening of depression and anxiety with the minimally important difference by comparing the proportions of participants showing a reduction of more than 0.5 s.d.s of the depression and anxiety scores at the 12-month assessment relative to the 3-month scores (Norman et al., Reference Norman, Sloan and Wyrwich2003). This analysis showed that comparable proportions of participants in gPM + (44, 30.8%) and EUC (38, 23.2%) worsened in terms of anxiety (χ 2 = 2.3, p = 0.13). There were more participants in gPM + (42, 29.4%) and EUC (26, 15.9%) worsened in terms of depression (χ 2 = 8.1, p = 0.004).

Discussion

Contrary to our hypotheses, gPM + did not show any benefit on the primary outcomes at the 12-month follow-up assessment. This pattern is in contrast to the observation that at 3-months gPM + led to greater reductions in depression. Further, the previously reported benefits of gPM + in reducing personally identified problems and inconsistent disciplinary parenting at 3-months were not maintained at 12 months. The finding that gPM + did not have longer-term benefits is consistent with prior evidence from more intensive programmes that have also reported that benefits of psychological interventions do not consistently persist, despite initial remission of symptoms (Paykel, Reference Paykel2007; Brouwer et al., Reference Brouwer, Williams, Kennis, Fu, Klein, Cuijpers and Bockting2019). There is evidence that more intensive psychotherapies for depression can have lasting benefit at 12 months (Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Quero, Noma, Ciharova, Miguel, Karyotaki, Cipriani, Cristea and Furukawa2021), however the current findings raise questions about the longevity of initial gains made with brief interventions, such as gPM + in populations experiencing ongoing stressors.

Several trials of (g)PM + have reported significant mental health benefits 3 months after participants received the intervention (Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani, Awan, Bryant, Dawson, Khan, Azeemi, Akhtar, Nazir, Chiumento, Sijbrandij, Wang, Farooq and van Ommeren2016; Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Schafer, Dawson, Anjuri, Mulili, Ndogoni, Koyiet, Sijbrandij, Ulate, Harper Shehadeh, Hadzi-Pavlovic and van Ommeren2017; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Khan, Hamdani, Chiumento, Akhtar, Nazir, Nisar, Masood, Din, Khan, Bryant, Dawson, Sijbrandij, Wang and van Ommeren2019; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Sangraula, Turner, Wang, Shrestha, Ghimire, Van't Hof, Bryant, Dawson, Marahatta, Luitel and van Ommeren2021; Bryant, 2022). This is the first report of a longer-term follow-up of people who have received individual or group PM + . Our findings suggest that initial gains achieved by this brief intervention may not be long-lasting. This pattern is underscored by the observation that depression severity worsened more frequently in gPM + than those in EUC. Equally it is possible that over the 12 months many participants in EUC achieved the reduction in depression initially made by gPM + participants in the first three months. That is, those refugees who received gPM + achieved a reduction in depression faster than those in EUC but both groups achieved comparable depression levels at 12 months. It perhaps is not surprising that the benefits of PM + did not persist at 12 months because the intervention delivered by non-specialists is meant to be brief in that it is only comprised of five group sessions and is low-intensity. The gains of this brief intervention may be particularly constrained in a population with a significant history of traumatic events and experiencing ongoing stressors in the refugee camp. One prior study of gPM + found that 31% of the treatment effect of gPM + was due to the use of PM + strategies (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Sangraula, Turner, Wang, Shrestha, Ghimire, Van't Hof, Bryant, Dawson, Marahatta, Luitel and van Ommeren2021), and it is possible that in the context of ongoing stressors in the camp use of these strategies may have waned. We note that we lack data to support this possibility, however in light of the greater reduction in depressive symptoms at 3 months that was not maintained at 12 months, one possibility is that the skills acquired during gPM + were not retained in the 12 months after the programme. It is also worth noting that the period between the 3- and 12-month assessments refugees around the world were adversely affected by a range of stressors arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, including lockdowns, impairments in resettlement, social isolation and shortage of supplies (Liddell et al., Reference Liddell, O'Donnell, Bryant, Murphy, Byrow, Mau, McMahon, Benson and Nickerson2021; Garrido et al., Reference Garrido, Paloma, Benitez, Skovdal, Verelst and Derluyn2022); these stressors have also been documented in Azraq camp (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Bawaneh, Awwad, Al-Hayek, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021a, Reference Akhtar, Heidrun Engels, Bawaneh, Bird, Bryant, Cuijpers, Hansen, Al-Hayek, Ilkkursun, Kurt, Sijbrandij, Underhill and Acarturk2021b). Further, most of the sample had probable PTSD, anxiety or depression, and these conditions are typically addressed with more intensive treatment programmes. Many recipients of PM + still experienced psychological problems after the programme (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Koyiet, Rahman, Schafer, Hamdani, Cuijpers, Sijbrandij and Bryant2022), and so it very well possible that these difficulties are exacerbated in the months after the gPM + , especially in the context of ongoing stressors.

It may be argued that one limitation of brief, lay-delivered interventions is that they do not have long-term benefits. However, there are possible means to address the apparent short-term benefits of gPM + . One potentially useful way to address this issue is by delivering augmentation strategies to maintain initial gains. Several options are available and need to be subjected to full investigation. First, booster sessions could be offered by lay providers to remind people of strategies taught in PM + , and to brain-storm how these can be applied to ongoing stressors; evidence that use of gPM + strategies wanes over time, and use of these strategies mediates symptom reduction after gPM + underscores the potential utility of booster sessions (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Kohrt, Sangraula, Turner, Wang, Shrestha, Ghimire, Van't Hof, Bryant, Dawson, Marahatta, Luitel and van Ommeren2021). Provision of booster sessions has been shown to be effective in preventing relapse for a range of psychological problems, including anxiety and depression (Gearing et al., Reference Gearing, Schwalbe, Lee and Hoagwood2013; Bruijniks et al., Reference Bruijniks, Lemmens, Hollon, Peeters, Cuijpers, Arntz, Dingemanse, Willems, van Oppen, Twisk, van den Boogaard, Spijker, Bosmans and Huibers2020). Second, stepped care programmes may have potential to triage more severely distressed people to more intensive programmes, whilst those with moderate distress may benefit from further brief interventions. There is evidence that stepped care programmes can be successfully implemented in LMICs (Araya et al., Reference Araya, Rojas, Fritsch, Gaete, Rojas, Simon and Peters2003; Patel et al., Reference Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary, Naik, Pednekar, Chatterjee, De Silva, Bhat, Araya, King, Simon, Verdeli and Kirkwood2010). These trials evaluated stepped care programmes relative to usual care, and so have not directly addressed whether they confer additive benefits over standard brief interventions, such as PM + . It is possible that provision of augmentation strategies following gPM + may also benefit participants who did not attend every group session because it can provide them with the opportunity to learn or reinforce strategies that may have not been adequately rehearsed during the initial gPM + programme.

It is interesting that 12 months after the intervention, refugees who received gPM + reported a greater increase in positive parenting relative to those in EUC. There is evidence that positive parenting is associated with better children's mental health, including in children in Arab contexts affected by war (Thabet et al., Reference Thabet, Ibraheem, Shivram, Winter and Vostanis2009). Further, parenting programmes that promote positive parental behaviours have been shown to be effective in improving adaptive parenting behaviours and children's mental health (Lindsay et al., Reference Lindsay, Strand and Davis2011). Programmes that have targeted caregivers' parenting skills have also reported improvements in adaptive parenting behaviours in contexts comprising refugees and other Arab settings affected by humanitarian crises (Lakkis et al., Reference Lakkis, Osman, Aoude, Maalouf, Issa and Issa2020; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Koppenol-Gonzalez, Arnous, Tossyeh, Chen, Nahas and Jordans2020). Notably, gPM + does not directly instruct in parenting behaviours, however it is possible that the skills taught in this programme may have led to alterations in parenting that are reflected in greater positive parenting scores. Alternately, improving caregivers' mental health may improve their parenting behaviour, which is one interpretation of findings that gPM + leads to better mental health and parenting (Bryant, 2022). We emphasise, however, that in the context of the primary outcomes and all other secondary outcomes being non-significant, this observation of greater positive parenting associated with gPM + may be a spurious finding and needs to be replicated before one can draw firm conclusions.

One of the curious findings of the 12-month follow-up was that PTSD severity reduced markedly in both the gPM + and EUC conditions. Several explanations may be offered for this pattern. First, between the 3-month and 12-month assessments the camp was directly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, resulting in lockdowns in the camp that often restricted people to their caravans, which could limit participants' exposure to trauma reminders that can activate trauma memories and other PTSD symptoms. Second, the restrictions during the pandemic may have led to participants feeling greater safety because of the restriction to their own caravans. Third, the impact of the pandemic and the associated restrictions on all residents in the camp may have resulted in those participants with PTSD symptoms re-evaluating their own psychological health, and this may have led to a degree of normalisation of their PTSD symptoms; this interpretation accords with evidence during the pandemic that people with more severe psychological problems reported less severe psychological difficulties relative to their pre-pandemic states (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Kok, Eikelenboom, Horsfall, Jorg, Luteijn, Rhebergen, Oppen, Giltay and Penninx2021).

We note several methodological limitations of the study. First, retention at the 12-month assessment was 74.9% of the original sample, which raises the possibility that results may have been influenced by a biased sample. This concern is underscored by the observation that more participants in the EUC condition were retained at 12 months relative to gPM + , and that those who were retained tended to have higher depression and PTSD scores at baseline. The nature of those who were and were not retained at 12 months raises questions over the robustness of intent-to-treat analysis approach; although our secondary analyses that focused only on those who completed the 12-month follow-up, we acknowledge that the biased nature of the follow-up sample may limit the extent to which we can confidently draw conclusions from the final data. Second, not all of the measures were properly culturally adapted, which limit the appropriateness of these measures to assess the intended constructs. There is much evidence that cultural context can play an important role in how mental health is experienced and reported, and that measures developed in the west may not fully capture the nuances of Syrian refugees' psychological responses (Hinton and Lewis-Fernández, Reference Hinton and Lewis-Fernández2011). For example, the PSYCLOPS, PG-13, PQ-B and APQ have not been culturally or psychometrically validated in this population, and this can be problematic with constructs such as grief, prodromal psychotic signs and parenting domains. Third, we could not objectively measure the services accessed by the EUC participants. Fourth, the control condition did not match gPM + for weekly contact with a facilitator or other group members, and in this sense the design could not isolate the effects of gPM + relative to nonspecific effects. Recent evidence highlights that gains in brief interventions may be attributed to nonspecific effects (Riello et al., Reference Riello, Purgato, Bove, Tedeschi, MacTaggart, Barbui and Rusconi2021), which highlights the need for control conditions that can dismantle the active ingredients of programmes. Finally, we recognise that these refugees had been in the camp for an average of five years and it is unknown how this lengthy period of displacement and detention may have impacted the longer-terms of gPM + . Further long-term follow-up assessments of refugee groups who have received gPM + and who have not been detained for such a lengthy period may yield different results.

Despite these limitations, the current findings suggest that the benefits of a brief, lay-provider intervention, such as gPM + , may not persist in the long-term. This conclusion does not undermine the utility of such interventions, which have been shown to effectively reduce common psychological disorders in people affected by adversity. The challenge for the field of global mental health is to develop ongoing programmes or service frameworks that can sustain the initial gains of effective interventions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796022000658.

Data

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available until the STRENGTHS consortium has completed independent participant data analyses in association with related studies but will be available from Richard Bryant (r.bryant@unsw.edu.au) after these IPD analyses are complete.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This project was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council-European Union Collaborating Grant (grant number 1142605) and European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Intervention Societal Challenges Grant (grant number 733337). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Conflicts of interests

The authors are declaring no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the King Hussein Cancer Centre in Jordan and the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee.