INTRODUCTION

Political scientists have long invoked values as a source of structure and stability in political attitudes (e.g., Feldman and Zaller Reference Feldman and Zaller1992; Hurwitz and Peffley Reference Hurwitz and Peffley1987; McCann Reference McCann1997) that does not rely on a sophisticated understanding of ideology (Goren Reference Goren2004; Goren, Smith, and Motta Reference Goren, Smith and Motta2022). Values such as humanitarianism, egalitarianism, conformity, and tradition help explain a variety of political attitudes and orientations (Goren et al. Reference Goren, Schoen, Reifler, Scotto and Chittick2016) with applications ranging from foreign policy (Rathbun et al. Reference Rathbun, Kertzer, Reifler, Goren and Scotto2016) to homelessness (Feldman and Steenbergen Reference Feldman and Steenbergen2001), as well as partisan and ideological polarization (Ciuk Reference Ciuk2023).

A more recent line of work, however, has posited that moral values, in particular, play a unique role in explaining public opinion. Moral values are said to be more relevant to politics and thus better predictors of a variety of political outcomes (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011; Kertzer et al. Reference Kertzer, Powers, Rathbun and Iyer2014; Koleva et al. Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012). Moral values may be especially useful in explaining growing polarization and animosity in politics. Some have suggested that “liberals and conservatives have a hard time seeing eye-to-eye because they make moral judgments using different configurations” of moral values (Clifford and Jerit Reference Clifford and Jerit2013, 659). Similarly, research shows that morally convicted attitudes are a unique driver of social distancing and polarization (Garrett and Bankert Reference Garrett and Bankert2020; Skitka, Bauman, and Sargis Reference Skitka, Bauman and Sargis2005). Thus, the study of moral values has quickly gained a prominent position in social psychology and political science.

While moral values have gained considerable attention in recent years, it is less clear whether and how moral values are distinct from other values. For example, the Schwartz value system includes 10 values, some of which are self-oriented and some of which are other-oriented. These other-oriented values, such as benevolence, clearly contain moral content and conceptually overlap with explicitly moral values, such as the moral foundation of care. Similarly, some political values, such as moral traditionalism, explicitly capture moral content. Others that are less clearly moralized, such as humanitarianism, are sometimes described in moral terms (Feldman and Steenbergen Reference Feldman and Steenbergen2001). Thus, in addition to conceptual overlap between moral and other value typologies, it remains unclear whether moral values are even uniquely moralized. As a consequence, it is unclear whether moral values provide additional leverage in explaining political divides.

Consistent with Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011, 368), we argue that “many values are moral values,” but many are not. Drawing on moral and evolutionary psychology, we argue that morality is fundamentally about cooperation (Curry, Mullins, and Whitehouse Reference Curry, Chesters and Van Lissa2019; Greene Reference Greene2013; Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Rai and Fiske Reference Rai and Page Fiske2011) and thus that moral values are distinguished by their focus on facilitating the pursuit of collective goals rather than self-interest. For example, values related to fairness serve to suppress cheating behavior to allow people to gain the benefits from trade. However, some values, such as self-direction or achievement (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2006), emphasize personal goals that are less relevant to cooperation, and thus should be less moralized. Moralization should, in turn, lead to greater divisiveness. Moralized claims are perceived as objectively and universally true (Goodwin and Darley Reference Goodwin and Darley2008; Skitka et al. Reference Skitka, Hanson, Morgan and Wisneski2021), and moral disagreement motivates punitive and exclusionary behavior (Ryan Reference Ryan2014; Skitka and Wisneski Reference Skitka and Wisneski2011). Thus, highly moralized values should be more powerful contributors to political polarization.

In this article, we study 21 values from three value systems: Schwartz’s personal values, political values, and moral foundations. Using a probability-based survey of the U.S. population, we directly assess value moralization and find substantial differences in value moralization both between and within value systems. We observe the highest moralization for a cluster of more liberal cooperative values (e.g., care, benevolence), followed by a cluster of more conservative cooperative values (e.g., authority, tradition). The lowest levels of moralization are observed for a cluster of self-focused values, such as stimulation and achievement. Finally, political values vary, but tend to fall between the two extremes. Using a preregistered conjoint experiment embedded in the survey, we show that value disagreement has substantively large effects on affective and social polarization. However, this effect is moderated by moral conviction such that value disagreement is much more polarizing for highly moralized values.

As the first study to directly examine the moralization of values that have been of interest to political science and psychology, our results illustrate important commonalities and differences: values that are meant to facilitate cooperation and suppress self-interest are perceived as highly moral, while more self-oriented, noncooperative values are not. These differences have important consequences, as the polarizing effects of value disagreement are much larger for highly moralized values. These findings suggest that it is important for future research on polarization to expand the scope of values under study and to consider the negative consequences of disagreement on moralized values for trust and cooperation in society.

VALUES AND MORAL VALUES

Values are defined as “trans-situational goals that vary in importance and serve as guiding principles in the life of a person or a group” (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2007, 712). Values tend to be central objects in belief systems that help to constrain and give meaning to specific political attitudes. Within political science, values have been used to explain a wide variety of political beliefs and attitudes, such as foreign policy attitudes (Kertzer et al. Reference Kertzer, Powers, Rathbun and Iyer2014; Kertzer and Zeitzoff Reference Kertzer and Zeitzoff2017), trait perceptions (Clifford Reference Clifford2014), social welfare attitudes (Feldman and Steenbergen Reference Feldman and Steenbergen2001), culture war attitudes (Clifford et al. Reference Clifford, Jerit, Rainey and Motyl2015; Koleva et al. Reference Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto and Haidt2012), and even partisan identity (Evans and Neundorf Reference Evans and Neundorf2020).

Yet, not all values are moral values. A large body of research from fields such as anthropology, economics, psychology, and neuroscience, holds that moral values are distinguished by their focus on solving cooperative problems (Curry, Mullins, and Whitehouse Reference Curry, Austin Mullins and Whitehouse2019; Enke Reference Enke2019; Greene Reference Greene2013; Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Rai and Fiske Reference Rai and Page Fiske2011). Throughout history, humans have faced a variety of cooperative problems (Sachs et al. Reference Sachs, Mueller, Wilcox and Bull2004), such as common pool resource problems (Gardner, Ostrom, and Walker Reference Gardner, Ostrom and Walker1990). To overcome those problems, humans have developed a suite of solutions in the form of moral values. For example, valuing reciprocity helps individuals overcome prisoner’s dilemmas in which self-interest leads to collectively worse outcomes. Those who do not reciprocate by returning favors and trusting others are judged because they inhibit cooperation and “accept the benefits of cooperation without paying the cost” (Curry, Mullins, and Whitehouse Reference Curry, Austin Mullins and Whitehouse2019, 49). Similarly, values such as group loyalty motivate individuals to carry out actions toward a shared goal, even at a cost to their own immediate self-interest. People police violations of group loyalty even when the violation does not directly affect them because it gets in the way of achieving collectively desirable outcomes (Haidt Reference Haidt2012). By endorsing these moral values and expecting others to do the same, we “achieve goals that we can’t achieve through collective selfishness” (Greene Reference Greene, Gazzaniga and Mangun2014, 1013). Thus, while there is considerable debate about the structure of moral values, it is widely agreed that moral values are defined by their function to “suppress or regulate selfishness and make cooperative social life possible” (Haidt Reference Haidt2012, 270).

Not all values are focused on cooperation, however. For example, Schwartz’s theory of basic human values includes several “self-enhancement” values. These values, which include hedonism, achievement, and power, are focused on the individual’s own success and gratification. Additionally, values that fall under the “openness to change” category, such as self-direction and stimulation, also focus on the self rather than the collective because the motivational goal of such values is “intrinsic interest in novelty and mastery” (Schwartz Reference Schwartz1994, 25). Because these values can be considered “egocentric concerns that emphasize what is best for the individual in her private life” (Goren et al. Reference Goren, Schoen, Reifler, Scotto and Chittick2016, 978–9), they are clearly less focused on cooperation and thus should be less likely to be considered moral values. If moral values are defined by their functional goal of suppressing selfishness and enabling cooperation (Haidt Reference Haidt2012), then the least moralized values should be those that focus on enhancing the self without an underlying social, collective goal.

COMPARING VALUE SYSTEMS

With the above framework, we now turn to discussing and comparing three common value systems that have been studied in political science and psychology.

Schwartz’s Theory of Basic Human Values

Shalom Schwartz’s theory of basic human values posits ten values (see Table 1) that are recognized across cultures and collectively satisfy three requirements of human existence: “needs of individuals as biological organisms, requisites of coordinated social interaction, and requirements for the smooth functioning and survival of groups” (Schwartz Reference Schwartz1994, 21). These values specify goals that are of value to the individual and motivate action on behalf of those goals, though the importance of each value varies across cultures and individuals.

Table 1. Schwartz’s Basic Human Values

Note: The defining goals are drawn from Schwartz (Reference Schwartz2006).

The ten values included in the Schwartz value system are theorized to be arranged in a circumplex, such that each value has an opposing value whose goals are in tension with each other. The circumplex can be further simplified by describing the values along two dimensions. The first dimension contrasts “openness to change” (stimulation, self-direction) with “conservation” (security, conformity, tradition) values. The fundamental tension on this dimension is between personal independence and social order and cohesion. The second dimension contrasts values of “self-enhancement” (achievement, power) with values of “self-transcendence” (universalism, benevolence). The fundamental tension on this dimension is between promotion of one’s own interests and success against concerns for the well-being of others.Footnote 1

Moral Foundations Theory

Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) is a pluralistic theory of morality that posits a small number of moral “foundations” that are universal and give shape to cultural differences in moral judgments. MFT takes an evolutionary approach, defining moral systems as “interlocking sets of values, practices, institutions, and evolved psychological mechanisms that work together to suppress or regulate selfishness and make social life possible” (Haidt Reference Haidt2008, 70). Thus, the theory leans heavily on the idea that the function of morality is to promote cooperation between individuals and within groups, but may take multiple forms depending on the nature of the relevant cooperative problem.

The most widely accepted version of MFT proposes five moral foundations that are grouped into two categories: individualizing and binding foundations. Both types of foundation serve to suppress selfishness in favor of cooperative goals, but in different ways. The “individualizing” foundations, care and fairness, capture norms about caring for the weak and vulnerable, and treating others fairly. The loyalty, authority, and sanctity foundations are “binding” foundations that constrain individuals to focus on protecting and enhancing the welfare of the group, such as the family or the country. They suppress selfishness through virtues of sacrifice, obedience, self-control, and chastity. Socialization and acculturation lead people to emphasize some foundations more than others, but the five foundations serve as building blocks of our own moral palettes.

There are of course many other theories of morality and considerable disagreement about the structure of moral values. Some have argued that the five original foundations are better described by the two higher-order concepts of individualizing and binding foundations (e.g., Harper and Rhodes Reference Harper and Rhodes2021). Others have reorganized and added to the foundations by focusing on prescriptive versus proscriptive motives (Janoff-Bulman and Carnes Reference Janoff-Bulman and Carnes2013). Other scholars reduce all of morality to harm, shifting the discussion of variation in moral values to variation in perceptions of harm (Schein and Gray Reference Schein and Gray2015). There are also challenges to the causal role moral foundations play in belief systems (Ciuk Reference Ciuk2018; Hatemi, Crabtree, and Smith Reference Hatemi, Crabtree and Smith2019; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Martin and Hatemi2017). Nonetheless, moral foundations theory remains the most influential and widely used theory of the structure of morality, so we focus our attention on it here, as originally conceived. Further, moral foundations theory, by virtue of its exclusive focus on moral values, provides a useful benchmark for comparison to a wider range of values.

By focusing exclusively on moral values, moral foundations theory makes an implicit assumption that the moral foundations are uniquely moralized—that is, that they are more likely to be interpreted in moral terms than other values. So far, this has remained an assumption. Some scholars have challenged the idea that the moral foundations are “intrinsically moralized,” suggesting that some purportedly moral foundations may be endorsed without being moralized (Schein and Gray Reference Schein and Gray2015). For example, Schein and Gray argue that some liberals may endorse the Authority foundation for pragmatic rather than moral reasons. Other scholars have argued that the theoretical core of the Sanctity (or Purity) foundation—avoiding pathogens—“is not a moral problem per se” (Curry, Chesters, and Van Lissa Reference Curry, Chesters and Van Lissa2019, 109). This argument suggests that concerns related to Sanctity should not be consistently moralized and it should not be considered a moral foundation. Both types of objections raise empirical challenges to moral foundations theory that have been largely unaddressed.

Political Values

Core political values are “abstract, prescriptive beliefs about humanity, society, and public affairs” (Goren Reference Goren2005, 882). While conceptually overlapping with some of the basic values and moral foundations discussed above, political values specifically aid citizens in making judgments about desirable political outcomes (Goren Reference Goren2001, 161), but do not necessarily function beyond the political domain. Political values are described as “inherently political predispositions” (Goren et al. Reference Goren, Schoen, Reifler, Scotto and Chittick2016, 981). There is evidence that political values are shaped by partisan identities (Goren Reference Goren2005; Goren, Federico, and Kittilson Reference Goren, Federico and Miki Caul2009).Footnote 2

Because of their closer relationship with political attitudes, political values are considered less abstract and less fundamental than basic human values (Schwartz, Caprara, and Vecchione Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010). Political values reflect value attitudes as they apply to the country and society, while Schwartz’s values are personal and thus universally applicable, i.e., domain-free. Indeed, some measures of political values include questions that directly ask about policy prescriptions. As discussed in Goren (Reference Goren2009), extant measures of political values mix “abstract normative beliefs” with “implicit policy prescriptions” (3). Schwartz, Caprara, and Vecchione (Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010) similarly explain that political values are measured based on “agreement with prescriptions for how government or society should function” (422). As a result, basic human values (as articulated by Schwartz) are theorized to be causally prior to political values, which in turn shape political attitudes. Evidence from a longitudinal study in Italy supports this contention, showing that political values fully mediate the effect of basic values on vote choice (Schwartz, Caprara, and Vecchione Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010). Therefore, while political values are related to Schwartz’s values, they are not redundant.Footnote 3 In other words, political values operate differently than the others discussed above and are likely downstream of basic or moral values.

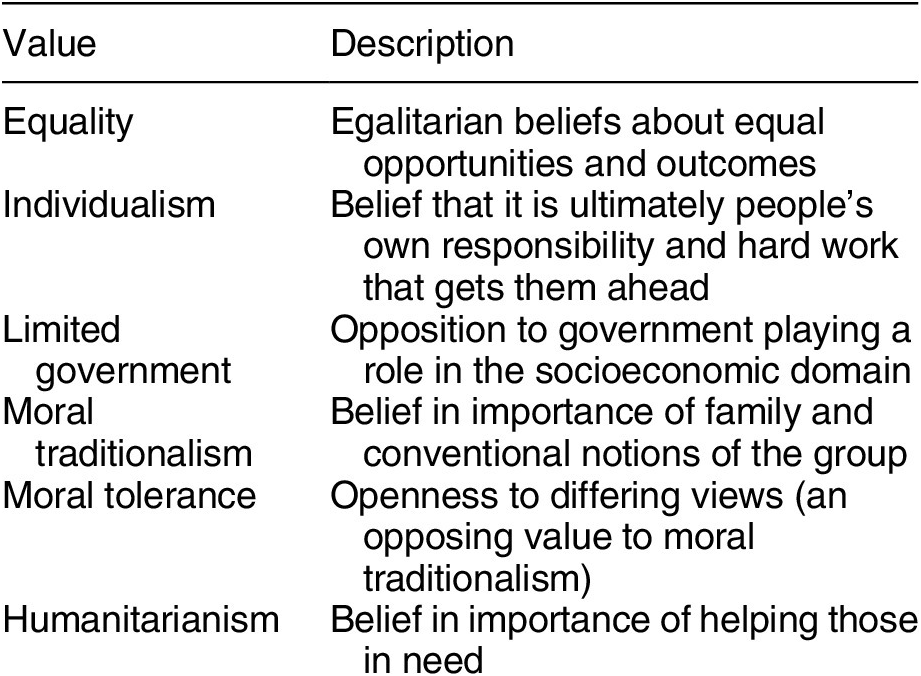

A wide variety of political values have been studied, but the most prominent values include equality, individualism, limited government, moral traditionalism, moral tolerance, and humanitarianism (Feldman and Steenbergen Reference Feldman and Steenbergen2001; Goren, Federico, and Kittilson Reference Goren2009). We explain each of the values in Table 2.

Table 2. Political Values

Cooperative and Noncooperative Values

Clearly, there is important conceptual overlap between value systems. In this section, we review the similarities between value systems and classify each value into one of three categories based on the fundamental goal of the value. The first category is noncooperative, or self-oriented values, such as achievement. The values in this category are the least explicitly cooperative. We use the term “noncooperative” to refer to values that are not clearly about cooperation and are thus least likely to be moralized. The term does not indicate that they are necessarily against cooperation or uncooperative. The remaining two categories are both clearly cooperative, but differ in their emphasis. As mentioned earlier, moral foundations theory makes a distinction between individualizing foundations (care and fairness), which emphasize the welfare of the individual, and binding foundations (authority, loyalty, sanctity), which emphasize the welfare of the group. Another way to conceptualize the distinction, drawing from work in economics, is that morality consists of universalist and communal morality (Enke Reference Enke2020; Enke, Rodríguez-Padilla, and Zimmermann Reference Enke, Rodríguez-Padilla and Zimmermann2023; Enke et al. Reference Enke, Fisman, Mota Freitas and Sun2023). As we discuss below, this basic distinction highlights that cooperative values vary in the breadth of cooperation. We hence classify cooperative values as either particularist, with cooperation being extended primarily to ingroup members, or as universalist, with benefits being extended more broadly. This distinction has parallels in all three value systems and is thus useful for distinguishing between types of cooperative values.

As discussed above, Schwartz’s values are classified into two dimensions: (a) openness to change versus conservation and (2) self-enhancement versus self-transcendence. Schwartz depicts the conservation and self-transcendence ends of each dimension as more socially focused and the openness and self-enhancement ends of each dimension as more personally focused. Schwartz (Reference Schwartz2006, 19) describes these socially focused values in explicitly cooperative terms, arguing that the most important values across cultures focus on “promoting and preserving cooperative and supportive relations among members of primary groups.” Supporting this view, the socially focused conservation and self-transcendence values consistently predict political attitudes while the more self-focused values of self-enhancement and openness do not (Goren et al. Reference Goren, Schoen, Reifler, Scotto and Chittick2016; Rathbun et al. Reference Rathbun, Kertzer, Reifler, Goren and Scotto2016). Thus, in Schwartz’s theory of basic human values, there is a clear distinction between cooperative (self-transcendence and conservation) and noncooperative values (self-enhancement and openness).

While conservation and self-transcendence values share a social, cooperative focus, they differ in their goals. Conservation values emphasize social order, commitment to tradition, and conformity to group norms. Conceptually, conservation values clearly overlap with the binding moral foundations, which emphasize group loyalty and obedience to authority. Thus, conservation values and binding foundations both fall together under the category of particularist cooperative values, which are about cooperation with people in one’s group. The political value of moral traditionalism, which emphasizes traditional gender roles and family structures, fits squarely within this category as well and is strongly related to the basic human values of security, conformity, and tradition (Schwartz, Caprara, and Vecchione Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010).

Self-transcendence values emphasize concern for the welfare of others and tolerance and protection of all people. Conceptually, self-transcendence values overlap with the individualizing moral foundations, which focus on care and concern for others and equal treatment. Thus, self-transcendence values and the individualizing foundations all fall under the category of universalist cooperative values, which is a broader form of cooperation that goes beyond one’s group and includes cooperation with people with whom one might not have personal connections. Among the political values, humanitarianism, equality, and moral tolerance clearly overlap with these universalist cooperative values (for relevant evidence, see Schwartz, Caprara, and Vecchione Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010).

The values that are most clearly noncooperative, or self-oriented, come from Schwartz’s basic human values. The values that fall under the openness category (self-direction, hedonism, stimulation) and the self-enhancement category (power, achievement) can be clearly classified as noncooperative. One might argue that these values are cooperative because, according to the Moral Motives Model (Janoff-Bulman and Carnes Reference Janoff-Bulman and Carnes2013), self-focused values such as self-restraint/moderation and industriousness have “important ramifications for the success and coordination of group living” (223). Janoff-Bulman and Carnes, however, also explain that the group consequences of such self-focused values are “distal” (221). Recall that noncooperative values are not uncooperative—they are just not directly about cooperation. Therefore, our categorization of Schwartz’s openness and self-enhancement values as noncooperative is largely consistent with the claims of the Moral Motives Model.

Moral foundations theory includes only values that are considered to be cooperative. The remaining political values of individualism and limited government pose more of a classification challenge, but can arguably be classified as noncooperative. Of course, one could argue that individualism and limited government are both moral values in the sense that they uphold notions of liberty that prevent tyranny and oppression (Iyer et al. Reference Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto and Haidt2012).Footnote 4 One might also argue that those values promote societal functioning, in line with the Moral Motives Model. Yet, these two values are typically expressed as a right to be free from social pressures and obligations to others in pursuit of one’s own interests. In this sense, these two political values are more closely related to self-oriented values of achievement, power, and self-direction. Supporting this claim, the strongest positive relationship between support for free enterprise (which relates closely to these two values) and any of Schwartz’s basic values is with power (Schwartz, Caprara, and Vecchione Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010). Moreover, individualism and limited government are more self-oriented values compared to other values within the system of political values, such as humanitarianism and moral traditionalism. As a result, we categorize these two political values as noncooperative, though we recognize there is room for disagreement. We emphasize that our division of values into cooperative and noncooperative is not black-and-white but is a simplification of a continuous dimension ranging from cooperative to noncooperative.

In short, while there are differences between the three value systems, there is also important overlap. Table 3 summarizes our efforts to organize the value space. The moral foundations are split into two types of cooperative values and should be the most highly moralized, though this has so far remained a contested assumption. The Schwartz values include a wider variety of values, some of which are more distant from cooperative goals, but also include cooperative values that are likely to be substantially moralized and overlap conceptually with the moral foundations. Finally, political values also fall into all three categories, though there is some ambiguity as to whether any are truly noncooperative.

Table 3. Typology of Cooperative and Noncooperative Values

THE CONSEQUENCES OF MORAL VALUES

If moral values are distinguished by their focus on cooperative goals, it makes sense that disagreements based in moral values, or “first principles” (Mooney Reference Mooney1999), might have outsized effects on conflict and polarization. As seen in Hardin’s (Reference Hardin1968) parable of the Tragedy of the Commons, uncooperative, self-interested action can lead to collective ruin. The problem of cooperation is thus “the problem of getting collective interest to triumph over individual interest” (Greene Reference Greene2013, 20). Whether a person endorses cooperative values thus has implications for one’s own well-being, as well as the well-being of friends and family.

According to multiple lines of research, moral beliefs and attitudes are distinguished by two related features that hold implications for cooperation. The first is objectivism—moral claims about the world are perceived as factual claims that are true or false (e.g., Goodwin and Darley Reference Goodwin and Darley2008). The second is universalism—people expect others, regardless of their culture, to endorse these moral claims (for a review, see Skitka et al. Reference Skitka, Hanson, Morgan and Wisneski2021). If a person rejects a moral claim, it generates strong reactions that are designed to “correct” that belief, attitude, or behavior. Moral disagreement generates strong emotional responses, such as anger and disgust (Ryan Reference Ryan2014) and stronger physiological responses (Garrett Reference Garrett2019), which in turn motivate action to reaffirm the moral view (Skitka and Wisneski Reference Skitka and Wisneski2011). These actions frequently serve to exclude others from the benefits of cooperation or to impose costs on noncooperative behavior in an attempt to facilitate cooperation (for a related argument, see Petersen Reference Petersen2012). To sum up, moral views are expected to be endorsed and adhered to by everyone, and disagreement can elicit strong reactions intended to correct others’ views.

Reactions to disagreement differ when morality is not at stake. Values that are not inherently cooperative are better characterized as matters of taste or preference, rather than right and wrong. Some people may value achievement, seeking to become the best in their field, while others do not. Whether a person greatly values personal achievement does not necessarily impact the well-being of those around them unless it is allowed to interfere with cooperative goals. As a result, disagreement over noncooperative values is more likely to be tolerated.

In short, value differences should matter most when those values are seen in terms of right and wrong. A person who does not share your moral values may be a threat to your well-being and to the well-being of those who are close to you. As a result, you might not only feel negatively toward people who do not share your view, but you might also want to exclude them from your social life for violating a social obligation. On the other hand, value differences that are not moralized might indicate a lack of similarity or shared interests without posing a potential threat. Thus, we expect that value disagreement will have a larger, more negative effect on evaluations of others when that value is highly moralized than when it is not. This interaction effect might be particularly large when considering outcomes that directly involve trust. A person’s cooperative intentions are central to the trust you can place in them, while the value they place in, say, stimulation or self-direction may be largely irrelevant. This logic might differ for outcomes that are less focused on trust, such as selecting a coworker or a person to get a drink with. For these outcomes, a person might place relatively more weight on task-relevant values, such as achievement or stimulation, or simply on shared values and interests. Nonetheless, we expect a larger effect of value disagreement for highly moralized values across a wide variety of outcomes related to polarization.

RESEARCH DESIGN OVERVIEW

We test our expectations about the moralization of values and the effects of value conflict on social polarization through a study conducted by Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS). The online study was fielded on a sample of 863 respondents from NORC’s probability-based AmeriSpeak Panel. The panel is nationally representative, uses area probability sampling, and has been used for well-known survey projects like the General Social Survey.Footnote 5

The survey consisted of two parts: an observational examination of value moralization and a preregistered experimental test of the effects of value disagreement.Footnote 6 In the first stage of the survey, respondents were asked to evaluate six randomly selected value statements drawn from 102 statements, which measure endorsement of the 21 values we evaluate here. Randomization was stratified such that each of a respondent’s six value statements were drawn from different values. After being presented with each value statement, respondents were asked to rate their agreement with it, then to report their level of moralization of that value before moving to the next value statement. We use data from this first section to test our expectations about levels of value moralization. Following this section, respondents completed an embedded conjoint experiment that allows us to test the interactive effect of value disagreement and value moralization on polarization. We describe this second section in detail below.

VALUE MORALIZATION

For the first section, we used questions that measure attitudes about the 21 values covered by Schwartz’s values, political values, and moral foundations. For each typology, we rely on the most common measurement approach. For moral foundations, we use the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011). The MFQ consists of a relevance section and a judgment section. The judgement section asks for level of agreement or disagreement with specific statements that contextualize each of the moral foundations (e.g., “I think it’s morally wrong that rich children inherit a lot of money while poor children inherit nothing”). The relevance section asks respondents to rate the moral relevance of fairly abstract statements related to the five moral foundations. An example in the Fairness domain is “Whether or not someone acted unfairly.” To enable us to offer all value statements in a common format, we converted the relevance items to agree–disagree statements (e.g., “It is important to me to never act unfairly”), all evaluated on a five-point scale.

To measure Schwartz values, we use Schwartz’s Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ-40), which measures basic personal values in a less cognitively demanding way than the original Schwartz Values Survey (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2003). The PVQ asks respondents to read a scenario implicitly describing a value that is important to a hypothetical person (e.g., “Thinking up new ideas and being creative is important to him. He likes to do things in his own original way”), then to rate how similar that person is to themselves. We adapted these items by asking respondents how much they agree or disagree with the statement of value importance. For example, an original portrait item for conformity that says “It is important to him to be obedient. He believes he should always show respect to his parents and to older people” has been adapted to “It is important to me to be obedient and to show respect for my parents and to older people.” These are general statements about the basic, personal values of an individual.

For political values, there is no single and comprehensive set of values and measures. Unlike the moral foundations and Schwartz’s values, “[t]here is no clear consensus regarding the number and content of core political values… nor is there a theory to help identify the universe of political values” (Schwartz, Caprara, and Vecchione Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010, 423). The closest thing to an authoritative source is the American National Election Study (ANES), but the values included in this survey are limited and vary from year to year. For this reason, we were forced to conduct our own review of the literature to identify the relevant political values. We were as inclusive as possible in this process, though we did limit this section of our review to the field of political science. For example, we use every value discussed in a review of the values literature (Goren Reference Goren2009). Selecting the appropriate measure of each value was also a challenge, as researchers have used different variations. We sought to collect more recent measures (under the assumption that any changes would be improvements on older versions) and to collect measures with the largest number of items to ensure appropriate coverage of the concept. Specific sources that we relied on for each individual scale are as follows: equality (Feldman and Steenbergen Reference Feldman and Steenbergen2001), humanitarianism (Feldman and Steenbergen Reference Feldman and Steenbergen2001), individualism (Feldman et al. Reference Feldman, Huddy, Wronski and Lown2020; Shen and Edwards Reference Shen and Edwards2005), moral traditionalism (Weisberg Reference Weisberg2005), moral tolerance (Goren Reference Goren2005), limited government (Goren Reference Goren2005). As shown in Supplementary Material A2, unlike our measures of Schwartz’s values, measures of political values tap into beliefs about the state of the world (e.g., country and society). All measures were already formatted to an agree–disagree scale, so they required no revisions. Supplementary Material A2 includes the full list of items for all three typologies that we used.

We assessed moralization using a modified version of a moral conviction question (Skitka and Morgan Reference Skitka and Morgan2014). Specifically, respondents were asked “to what extent is your response to this statement connected to your fundamental beliefs about right and wrong?” Response options were on a five-point scale ranging from “not at all” (1) to “very much” (5). This question has the benefit of being face valid, as well as being extensively validated in the psychological literature.Footnote 7

Results

We stack the data such that each respondent provides up to six observations, with a total of 5,145 respondent-items. We restrict the data to respondent-items for which the respondent endorses the relevant values (n = 3,189) so that we estimate moralization only among those who endorse a value (rather than moralized opposition to a value). This choice is important because respondents who oppose a value may do so for very different reasons than respondents who support a value.Footnote 8

As a first step, we compare the three typologies to each other, averaging across values and items. To do so, we estimate the level of moralization as a function of dummy variables for each typology. We also include respondent random effects. The estimated mean levels of moralization for each typology are shown in Figure 1. The moral foundations receive the highest average moralization (3.95). This is expected, given the explicitly moral content of moral foundations that is based in theories of cooperation. This average is significantly higher than the average moralization of Schwartz values (3.58; p < 0.001) and the average for political values (3.66; p < 0.001), which are not significantly different from each other (p = 0.096). While the values defined by moral foundations theory are indeed more moralized among the public, all three typologies are moderately moralized, scoring above the midpoint of the scale (“somewhat”). This suggests that moralization is not unique to moral foundations.

Figure 1. Moralization at the Typology Level

Note: Moralization estimates from an OLS model that regresses moral conviction on typology dummy variables and respondent random effects. These are coefficient estimates for the three typologies calculated in the model without an intercept. Full model results are available in column 3 of Supplementary Table D1 in the Supplementary Material on the Dataverse.

However, we expect there to be considerable variation within each typology. To examine this variation, we estimate a model similar to the one described above, but with fixed effects for each value, rather than each typology. The mean levels of moralization for each value are shown in Figure 2. Here, we see again that moral foundations are generally more moralized than Schwartz values and political values. The care foundation receives the highest moralization score (4.25) of any value tested, consistent with it being a central component of morality (Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Hofmann et al. Reference Hofmann, Wisneski, Brandt and Skitka2014, 1342). The Fairness foundation is not far behind (4.18). These are our universalist cooperative values listed in Table 3. The three binding foundations (loyalty, authority, and sanctity), which fall under particularist cooperative values, receive more moderate levels of moralization, though the sanctity foundation scores somewhat higher than the other two (3.78, 3.53, 3.90, respectively). This is consistent with narrower adoption of these values within the American public (Graham, Haidt, and Nosek Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009).Footnote 9

Figure 2. Moralization at the Value Level

Note: Moralization estimates from an OLS model that regresses moral conviction on value dummy variables and respondent random effects. These are coefficient estimates for the 21 fixed effects calculated in the model without an intercept. The value system of each of the values on the vertical axis is indicated with “S” for Schwartz values, “P” for political values, and “MF” for moral foundations. Full model results are available in column 3 of Supplementary Table D2 in the Supplementary Material on the APSR Dataverse (Jung and Clifford Reference Jung and Clifford2024).

Within the Schwartz values, there is a clear distinction between cooperative and noncooperative values. Starting with cooperative values, consistent with the MFT results, the universalist values of benevolence and universalism receive high moralization scores (3.98, 4.02, respectively) that are not significantly different from moralization scores for fairness (p = 0.059 and p = 0.121, respectively), though significantly lower than the moralization scores for care (both ps < 0.05). Among the particularist cooperative values, there is wider variation. Conformity (4.02) rates as high as Schwartz’s universalist cooperative values of benevolence and universalism, while tradition (3.63) and security (3.47) rate similar to the particularist moral foundations. Together, there are clear similarities between the findings for MFT and cooperative Schwartz values—the universalist values are all highly moralized, while the particularist values are generally less so. This makes sense in light of the conceptual similarity between the moral foundations and some of the basic values (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva and Ditto2011).

The remaining values in the Schwartz system are all noncooperative and should thus be the least moralized. With the exception of self-direction (3.46), these values receive relatively low levels of moralization ranging from 2.92 (power) to 3.15 (hedonism). Still, the moralization estimate for self-direction reaches only the lowest end of the cooperative values, as we discuss in more detail below. These low levels of moralization are consistent with expectations and help explain the lower average moralization scores for the Schwartz value system.

Finally, we turn to political values. The universalist cooperative value of humanitarianism stands out with the highest level of moralization (4.00), similar to other values in that category such as fairness, benevolence, and universalism. The two other universalist cooperative political values—moral tolerance and equality—fall between 3.6 and 3.7, which is roughly on par with the particularist moral foundations (authority and loyalty). The only particularist political value, moral traditionalism, falls between the particularist moral foundations and the particularist basic values.

Limited government and individualism score the lowest among the political values at 3.5 and 3.3, respectively. These findings are consistent with the notion that these values are less focused on cooperation. According to Schwartz, Caprara, and Vecchione (Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010), the political value of free enterprise is related to “achievement and power because economic individualism allows unfettered pursuit of own success and wealth” (430). While limited government and individualism are relatively noncooperative, in comparison with other political values, they have similar levels of moralization as two particularist Schwartz values (security and tradition) and the particularist moral foundation of authority. This indicates that while limited government and individualism are best characterized as noncooperative values in comparison with values within the typology of political values (as we categorized in Table 3), they have cooperative elements that make them on par with particularist cooperative values when comparing between value typologies. It might be that people who endorse limited government or individualism do so because they believe that such behaviors support local norms and proper functioning of societies and groups.

Overall, these results suggest that moralization varies meaningfully between and within value systems.Footnote 10 While moralization is on average higher for moral foundations, this masks variation within value systems, particularly among the Schwartz values. At the value level, the level of moralization generally corresponds with the focus of the value, with universalist cooperative values being the most moralized (e.g., care, benevolence, humanitarianism), particularist cooperative values come next (e.g., authority, security, moral traditionalism), and noncooperative values the least (e.g., stimulation, achievement, individualism).Footnote 11 In short, in line with theories about the importance of cooperation to morality, cooperative values tend to be more moralized in the general population.

So far, our results demonstrate that there are considerable differences in the moralization of different values. We expect these differences across values and the underlying cooperativeness of moral values to have important implications for social polarization. In general, we expect that value disagreement will cause social polarization. However, this effect should be larger for values that are moralized to a greater degree and on outcomes that involve social interaction with the disagreeing individual.

THE EFFECTS OF VALUE CONFLICT ON SOCIAL POLARIZATION

After respondents rated their value endorsement and moralization, they participated in a conjoint experiment designed to test the effects of value disagreement.Footnote 12 The primary analysis, discussed below, is preregistered. Respondents were told that researchers are interested in the factors that contribute to friendship and that they would be asked to evaluate six hypothetical people. Each vignette provided a basic description of a person, including age, gender, race, partisan identification, job, religion, education, favorite hobby, and a value position.Footnote 13 For each of the six vignettes, the hypothetical person was assigned to one of the value statements evaluated by the respondent earlier in the survey such that each of the six values were presented in a vignette in random order. Within each vignette, the hypothetical person was randomly assigned to agree or disagree with the value statement. The full set of values for each variable is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Conjoint Variables and Values

Following each vignette, respondents answered three questions assessing different, but related aspects of social polarization: favorability, social distance, and trust. To measure favorability, respondents were asked how “positive or negative” they feel toward the person on a seven-point scale. To measure social distance, respondents were asked to rate how “happy or unhappy” they would be to have the person as a neighbor using a five-point scale. To measure trust, respondents were asked how comfortable they would feel having this person look after their house while they are out of town (measured on a five-point scale). All three variables are scaled to range from 0 to 1 with larger values indicating more favorable or trusting attitudes. We chose these three outcomes because they vary in the extent to which they involve social interaction with the hypothetical individual. Favorability is a general attitude expressed in a context that does not entail any interaction with the other person. Attitude about having the other person as a neighbor is a measure of how socially proximate one is willing to be. Comfort about house-sitting is a measure of trust, as it reflects ease about having that person enter one’s personal and private space. The interactive effect of value moralization and value disagreement on polarization should be greater in the context of more direct, social interaction with the disagreeing individual, i.e., for social distance and trust than for favorability.

Results

For the analysis of the conjoint experiment, we first stack the data such that each respondent provides up to six observations. We use OLS regression with standard errors clustered on the respondent. To provide an initial exploratory look at the data, before examining the interactive effect of value disagreement and value moralization, we predict the dependent variable as a function of value disagreement and control for levels of each of the placebo items. This exercise helps us understand the size of the average effect of value disagreement relative to other attributes in the experiment. The disagreement variable takes the value of “1” if the respondent endorses (rejects) the value and the hypothetical person rejects (endorses) the value. The analysis therefore excludes respondents who did not express an opinion about the value.Footnote 14 To account for partisanship, we create two dummy variables representing shared (e.g., Democrat and Democrat) and opposing party identification (e.g., Democrat and Republican). For all cases in which either the respondent identifies as a pure independent or the hypothetical person identifies as an independent both dummy variables are coded as zero.Footnote 15

Figure 3 displays the results. The dependent variable averages the three outcomes into a single index (scaled to range from 0 to 1). Value disagreement, relative to value agreement, has the largest effect of any of the variables. It reduces the index by 0.11 or about 0.57 standard deviations. For contrast, the difference between the total effect of shifting from a copartisan to an out-partisan causes a reduction of 0.09.Footnote 16 These effect sizes highlight that value difference plays a large role in polarization, beyond the role of difference in party identity, which has received much attention in prior work on polarization (e.g., Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). In Supplementary Material A5, we show that the results are similar when we run separate models for the three outcomes (Favorability, Neighbor, and House). All in all, the effect of value disagreement—averaging across all 21 values—is substantively quite large.

Figure 3. Main Effect of Value Disagreement

Note: Effect of value disagreement compared to effects of partisanship and other placebo items. OLS model with respondent-clustered standard errors. Outcome variable is an index averaging responses to Favorability, Neighbor, and House. Full model results are available in Supplementary Table D7 of the Supplementary Material on the APSR Dataverse (Jung and Clifford Reference Jung and Clifford2024).

We now turn to our preregistered tests of our main hypothesis—that the effect of value disagreement will be moderated by the extent to which a respondent moralizes the relevant value. To test this hypothesis, we extend the model above by adding a measure of moralization (i.e., moral conviction) and an interaction between moral conviction and the value disagreement dummy.Footnote 17 As expected, there is a significant interaction between moral conviction and value disagreement for all three outcome variables (ps < 0.001). The interaction coefficients are −0.019, −0.026, and −0.025 for the Favorability, Neighbor, and House outcomes, respectively (see Supplementary Material A6 for full model results). We also explored how these interactions differ across outcomes.Footnote 18 As one might expect, the slopes are indeed steeper for Neighbor and House—the two more socially interactive outcomes—than for Favorability, though these differences are not statistically significant (p = 0.061, p = 0.264, respectively). To further illustrate the results, Figure 4 plots the marginal effects of value disagreement across the range of moral conviction for each of the three dependent variables. Starting with favorability, the effect of value disagreement ranges from −0.09 at the lowest level of moral conviction to −0.16 at the highest level. The results are more dramatic for the two outcomes that focus on social interaction. The effect of value disagreement on the Neighbor (social distance) outcome roughly triples in size from a low of −0.05 (at lowest level of moral conviction) to a high of −0.15 (at highest level of moral conviction). For the House (trust) outcome, the effect of value disagreement more than quadruples in size, from −0.03 to −0.13.

Figure 4. Moral Conviction Moderates the Effect of Value Disagreement

Note: Marginal effects of value disagreement across levels of moral conviction. OLS models including partisanship and other placebo variables, with respondent-clustered standard errors. Full model results are presented in Supplementary Table A3 of Supplementary Material A6.

Another way to interpret these results is that the treatment effect differs more clearly across outcomes at low levels of moralization. As mentioned, at the lowest levels of moral conviction, treatment effects are −0.09, −0.05, and −0.03, for Favorability, Neighbor, and House, respectively. The marginal effect on Favorability is significantly larger than the corresponding marginal effect for both Neighbor (p < 0.001) and House (p < 0.001),Footnote 19 which means that disagreement over nonmoral values is more relevant to favorability than for social distance and trust. This makes sense because it indicates that disagreement over nonmoral values, which does not clearly signal cooperative consequences, has little to no effect on explicitly cooperative outcomes. In comparison, favorability, as a more general attitude, is influenced to a greater extent by value disagreement even when those values have little cooperative relevance. To summarize, value disagreement has a much larger impact when the value is highly moralized, and this pattern is especially pronounced for outcomes that invoke cooperation.

Our findings are robust to a number of alternative model specifications. Following the preregistration, we tried including respondents who do not have a position about the focal value, i.e., those who chose “Neither agree nor disagree” and running models with an additional interaction between an indicator for those who chose the middle category and stated level of moral conviction. We also ran models that include respondent fixed effects. Furthermore, following the moralization analyses in the first part of this article, we restricted analyses to respondents who endorse a value. This allows us to examine how moral conviction interacts with value disagreement between value endorsers and hypothetical value rejectors. We continue to find the same results; see Supplementary Material A6.Footnote 20

While the previous analysis strongly supports our prediction, it relies on individual-level variation in moral conviction. However, we also expect the effect of value disagreement to vary across values, on average. Considering the variation in moralization found in Figure 2, we expect that differences in moralization of those values, on average, help explain those value-level differences. To test this expectation, we extended our main effects model for Figure 3 above by adding an interaction between value disagreement and the focal value, providing estimates of the effect of value disagreement for each value. Other features of the model specification are the same. As an initial test, we use the averaged index of attitudes as the outcome variable.

In Figure 5, we plot the estimated effects of value disagreement at the value level (y-axis) with the average level of moralization (x-axis) derived from Figure 2.Footnote 21 Overall, there is a strong relationship between moralization and the effect of value disagreement at the value level (r = −0.82, p < 0.001, n = 21) such that more moralized values have more polarizing effects. The range of results is meaningful as well, with the treatment effect ranging from a low of −0.04 to a high of −0.21. The four most polarizing values are benevolence, universalism, care, and fairness. These four values all fall under universalist cooperative values. Several particularist cooperative values (Schwartz’s conformity and security values and the loyalty moral foundation) are close behind. In short, disagreement over cooperative values tend to be the most polarizing. Three of the least polarizing values are hedonism, achievement, and stimulation, which are noncooperative values from the Schwartz typology. Thus, there is clearly a close correspondence between moralization and polarization.

Figure 5. Value-Level Moralization and Disagreement Effect, Averaged Outcome

Note: On the horizontal axis are moralization estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) from Figure 2. Vertical axis presents the effects of value disagreement (along with 95% CIs) in an extension of the model in Figure 3 where value disagreement is interacted with value dummy variables. Full model results are presented in the first model of Supplementary Table A6 in Supplementary Material A7.

In Figure 6, we present the same set of analyses for the three outcome variables separately.Footnote 22 Across all three outcomes, the effect of disagreement is indeed generally larger for values that are more moralized, on average. The correlations between value moralization and disagreement effects are −0.79, −0.73, and −0.79 for the favorability, social distance, and trust outcomes, respectively. As seen by the confidence intervals that do not cover zero, value disagreement has negative effects on favorability even for the least moralized values. However, when considering social distance with a neighbor and trusting to house-sit, value disagreement matters consistently only when the target value is highly moralized. To put it differently, all types of value disagreement may matter for whether you like a person, but it is disagreement on moral values that matters for interactions that require trust. This finding is further evidence that the cooperativeness of moral values makes them uniquely divisive.

Figure 6. Value-Level Moralization and Disagreement Effect, Separate Outcomes

Note: The x-axis displays moralization estimates (and 95% confidence intervals) for each of the 21 values (estimates from Figure 2). The y-axis displays the estimated effect of value disagreement for each value on Favorability, Neighbor, and House, separately. Full model results are presented in models 2, 3, and 4 of Supplementary Table A6 in Supplementary Material A7.

CONCLUSION

In recent years, many scholars and pundits have sought to explain increasing political polarization and acrimony in terms of irreconcilable value conflict—particularly over deeply held moral values. Yet, scholars have relied on a variety of competing value typologies, some of which are explicitly moral and some of which are not. Further, there has been little attempt to compare value typologies from either a theoretical or empirical standpoint. In this article, we have contributed the first systematic inquiry of value moralization. Across 21 values from three common value typologies, we find considerable differences in the extent to which people moralize values. On average, the moral foundations receive the highest levels of moralization. Yet, these typology-level differences hide considerable variability. Following our theoretical classification, we find that cooperative values are more moralized than noncooperative values. Among cooperative values, universalist ones are more moralized than particularist ones. Taken together, these findings suggest that there are considerable similarities in moralization across value typologies, but important differences within each that are influenced by the substantive focus of the value.

While the moral foundations received slightly higher levels of moralization, they are by no means unique in this regard. Many of the basic human values yielded similarly high levels of moralization and were just as polarizing, particularly those that conceptually overlap with the moral foundations. Of course, this does not imply that the moral foundations are redundant to Schwartz’s basic values. The moral foundations may include substantive content that is missing from the basic values, such as concerns about fairness or sanctity. Thus, further work is needed to examine the substantive overlap between value systems (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Brandt, Swedlow and Turner-Zwinkels2022).

Our results also show that different values can have different consequences. Using a conjoint survey experiment, we showed that value disagreement has a larger effect on social polarization when an individual perceives the value as moral. These effects aggregate up to produce substantially different effects across values. For the least moralized values, disagreement has only a modest effect on social polarization and even null effects on our measure of trust. However, for the most moralized values, disagreement has large negative effects on trust, social distance, and favorability. Consistent with the cooperative nature of moral values, the interactive effect of value disagreement and value moralization is greatest when it is an outcome that involves social interaction with the disagreeing individual.

Our findings should also prove valuable in furthering our understanding of how specific attitudes become moralized. A common argument in this nascent literature is that attitudes become moralized when they can be tied to broader moral principles or beliefs (e.g., Feinberg et al. Reference Feinberg, Kovacheff, Teper and Inbar2019; Kodapanakkal et al. Reference Kodapanakkal, Brandt, Kogler and Beest2022; Skitka et al. Reference Skitka, Hanson, Morgan and Wisneski2021). For example, research shows that moral frames tend to moralize attitudes, while nonmoral frames do not (Kodapanakkal et al. Reference Kodapanakkal, Brandt, Kogler and Beest2022). However, in the absence of empirical evidence as to which values are moralized, researchers have little guidance as to the types of frames and persuasive messages that will moralize issue-specific attitudes and the types that will not. By providing a theoretical framework and systematic evidence for the moralization of a large number of values, we aid scholars in developing theories of when and why policy attitudes become moralized. An implication of our findings is that frames and messages that appeal to cooperative values are most likely to contribute to attitude moralization, while appeals to more self-oriented values are likely to persuade without leading to attitude moralization.

Finally, our evidence on the consequences of value disagreement and moralization holds important implications for research on political polarization. Some scholars have offered observational evidence that core values have contributed to partisan-ideological sorting and affective polarization (e.g., Enders and Lupton Reference Enders and Lupton2021; Lupton and McKee Reference Lupton and McKee2020; Lupton, Smallpage, and Enders Reference Lupton, Smallpage and Enders2020). Yet, this research relies on a limited set of political values that happen to be available in large national surveys (e.g., the ANES). Our findings suggest that the particular value selected for study may have an important impact on the findings in this type of research. Since we find that substantively cooperative values that are meant to promote collective interest tend to be more moralized than self-oriented values, the implication is that future survey projects should include more questions from other value typologies, i.e., basic values and/or moral foundations. Overall, our results hold important implications for the values that are most relevant to debates about polarization and for understanding how specific issues become polarized.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055424000443.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MLJQQN.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the anonymous reviewers, editor, Patrick Kraft, and Tim Ryan for helpful comments. Earlier versions were presented at the 2022 American Political Science Association conference, the 2023 European Political Science Association conference, and the Models, Experiments, and Data (MEAD) Workshop at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by University of Houston and Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the University of Houston and certificate numbers are provided in the Supplementary Material. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the principles concerning research with human participants laid out in APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research (2020).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.