Introduction

Stonehenge, a Late Neolithic–Early Bronze Age monument in Wiltshire, southern England, was constructed in five stages between around 3000 BC and 1500 BC (Darvill et al. Reference Darvill, Marshall, Parker Pearson and Wainwright2012). The first stage consisted of a circular ditch enclosing pits thought to have held posts or standing stones, of which the best known are the 56 Aubrey Holes. These are now believed to have held a circle of small standing stones, specifically ‘bluestones’ from Wales (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009: 31–33). In its second stage, Stonehenge took on the form in which it is recognisable today, with its ‘sarsen’ circle and horseshoe array of five sarsen ‘trilithons’ surrounding the rearranged bluestones.

Starting in 2003, the Stonehenge Riverside Project explored the theory that Stonehenge was built in stone for the ancestors, whereas timber circles and other wooden structures were made for the living (Parker Pearson & Ramilisonina Reference Parker Pearson1998). Stonehenge has long been known to contain prehistoric burials (Hawley Reference Hawley1921). Most were undated, so a priority for the project was to establish whether, when and in what ways these dead were associated with the monument. Until excavation in 2008, most of the recovered human remains remained inaccessible for scientific research, having been reburied at Stonehenge in 1935 (Young Reference Young1935: 20–21).

Stonehenge's human remains

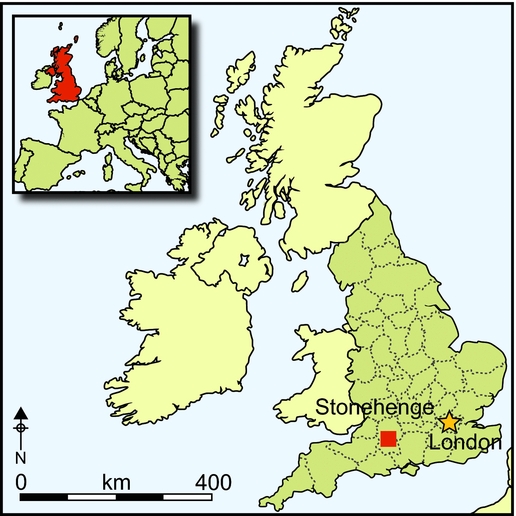

As reported in a previous issue (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009), radiocarbon dating of museum specimens of human bone from Stonehenge (Figure 1) reveals that they date from the third millennium BC (Late Neolithic) to the first millennium AD (Pitts et al. Reference Pitts, Bayliss, McKinley, Boylston, Budd, Evans, Chenery, Reynolds and Semple2002; Hamilton et al. Reference Hamilton, Pitts and Reynolds2007; Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009; Parker Pearson & Cox Willis Reference Parker Pearson, Cox Willis, Furholt, Lüth and Müller2011). Most of the human remains from Stonehenge were cremated, the excavated sample being recovered largely as cremation deposits by William Hawley between 1920 and 1926. Of these cremated bones, the larger components recognised and hand-collected by Hawley were later reburied, unanalysed, in Aubrey Hole 7 in 1935 (Young Reference Young1935: 20–21). This material was re-excavated in 2008 by the Stonehenge Riverside Project in order to assess demographic structure, recover pathological evidence and date the burial sequence at Stonehenge. Aubrey Hole 7 was itself investigated to explore whether the Aubrey Holes had formerly held standing stones—the Welsh ‘bluestones’ (Hawley Reference Hawley1921: 30–31; Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009: 31–33).

Figure 1. Stonehenge and its environs on Salisbury Plain (drawn by Josh Pollard).

Hawley excavated cremated remains from many contexts across the south-eastern half of Stonehenge, including the fills of 23 of the 56 Aubrey Holes (AH2–AH18, AH20–AH21, AH23–AH24 & AH28–AH29), the Stonehenge enclosure ditch and the area enclosed by that ditch (Figure 2; Hawley Reference Hawley1921, Reference Hawley1923, Reference Hawley1924, Reference Hawley1925, Reference Hawley1926, Reference Hawley1928). Most of the cremation deposits within the enclosure were found clustered around Aubrey Holes 14–16, with only one (2125) from the centre of the monument, just outside the sarsen circle. Fifty-nine deposits of cremated bone are identifiable from Hawley's records. There was a single grave good: a polished gneiss mace-head from a deposit within the enclosure's interior (Hawley Reference Hawley1925: 33–34; Cleal et al. Reference Cleal, Walker and Montague1995: 394–95, 455); pyre goods of bone/antler skewer pins were recovered from Aubrey Holes 5, 12, 13 and 24, and from a deposit in the ditch (Cleal et al. Reference Cleal, Walker and Montague1995: 409–10). A ceramic object from a disturbed deposit of cremated bone in Aubrey Hole 29 may also be a grave good (Hawley Reference Hawley1923: 17; Cleal et al. Reference Cleal, Walker and Montague1995: 360–61).

Figure 2. The distribution of third millennium BC burials (in red) at Stonehenge; Aubrey Hole 7 is in the east part of the circle of Aubrey Holes (drawn by Irene de Luis, based on Cleal et al. Reference Cleal, Walker and Montague1995: tab. 7).

Hawley noted that several of the burial deposits had circular margins, suggesting that they had been placed in organic containers such as leather bags. He states that: “in every case [the burials in the Aubrey Holes] had apparently been brought from a distant place for interment” (Reference Hawley1928: 158).

Young (Reference Young1935) recorded that four sandbags of bones were brought to the site for reburial in 1935. On re-excavation in 2008, the remains formed an undifferentiated layer at the base of Aubrey Hole 7 (Figure 3). Consequently, it was not possible to distinguish visually either the material from the four sandbags or the original 59 cremation deposits, or to relate the remains to the grave or pyre goods. The remains were re-excavated by spit (50mm) and by grid (50mm × 50mm) to allow the formation process to be studied through osteological analysis. The distribution of discrete skeletal elements (e.g. occipital bones, internal auditory meatus (IAM)) deriving from different individuals showed, however, no spatial patterning. This suggests that the remains were thoroughly commingled on deposition rather than having been packed separately by context as individual burials.

Figure 3. Cremated human remains being excavated from the base of Aubrey Hole 7 by Jacqui McKinley and Julian Richards. The bone fragments were deposited in this re-opened pit in 1935 (photograph: Mike Pitts).

During re-excavation of Aubrey Hole 7 (Figures 4 & 5), the remains of a hitherto unexcavated cremation burial (007), unaccompanied by any grave goods, was identified on the western edge of the Hole. It had a circular margin indicative of a former organic container and was set in its own shallow, bowl-shaped grave (Figure 6).

Figure 4. Aubrey Hole 7 after removal of the re-deposited cremated bone fragments, viewed from the south. The hole for the intact cremation burial is on the left side of the pit.

Figure 5. Plan of Aubrey Hole 7 and the intact cremation burial to its west (in Cut 008; drawn by Irene de Luis).

Figure 6. The intact cremation deposit of an adult woman beside Aubrey Hole 7 during excavation, viewed from the south (photograph: Mike Pitts).

The remains (1173.08g) were identified as those of an adult woman, and were dated to 3090–2900 cal BC (95% confidence; SUERC-30410, 4420±35 BP; and OxA-27086, 4317±33 BP; providing a weighted mean of 4366±25 BP). No stratigraphic relationship survived between the grave and the Aubrey Hole. An adult cremation burial made within the primary fill of Aubrey Hole 32 is dated to 3030–2880 cal BC (OxA-18036, 4332±35 BP; Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009: 26), so burial 007 may be broadly contemporary with the digging of the Aubrey Holes.

The discovery of this grave beside Aubrey Hole 7, in an area already excavated during the 1920s, provides a reminder that Hawley's methods were not particularly thorough (McKinley Reference McKinley, Cleal, Walker and Montague1995: 451–55; Pitts Reference Pitts2001: 116–21). An idea of these methods is provided by a diary entry for 25 March 1920: “We sieved the cremated bones [from AH9], keeping the larger ones and casting away the sifted remnant after thoroughly searching” (Hawley Reference Hawley1920: 73). The deposits of bone that Hawley found varied from scattered fragments to the remains of burials; during excavation of Causeway crater 2 on 7 November 1922, he noted that: “There were odd pieces of cremated bone met with occasionally and at one spot about a handful in a small mass” (Hawley Reference Hawley1922: 129). We cannot rule out the possibility that some of these remains might be multiple deposits from single cremations; there may have been a variety of methods of deposition (McKinley Reference McKinley and Smith2014).

Thus, any assessment of the numbers of such remains and other forms of cremation-related deposits recovered by Hawley must take into account the likelihood that his retrieval was incomplete. Estimates for the total number of cremation burials at Stonehenge, which range from 150 (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009: 23) to 240 (Pitts Reference Pitts2001: 121), must remain informed guesswork.

Ages of the individuals from Aubrey Hole 7

During examination of the well-preserved bone retrieved from Aubrey Hole 7 in 2008, a minimum number of individuals (MNI) of 22 adults and five sub-adults was determined by counting the most frequently occurring skeletal element in each of the broad age categories. Fragments of 24 right petrous temporal bones (incorporating internal auditory meati (IAM)) were identified. The second most commonly recovered skeletal element is the occipital bone, of which 22 adult examples were recovered.

The MNI of five immature individuals represented in the assemblage was established by looking for the most frequently occurring duplicate elements, and noting obvious age-related differences in bone growth and development. There was no duplication of skeletal elements within any of the sub-adult age categories, so it can be assumed that only one individual is represented from each (Table 1). Shrinkage was taken into consideration in determining broad age ranges, but more precise determinations of age at death were not possible owing to the fragmented nature of the cremated bones (see McKinley Reference McKinley1997: 131).

Table 1. Ageing descriptions for bone fragments from Aubrey Hole 7, identifying those bones from which age was determined in each category. The occipital bones and internal auditory meati do not appear in this table; the full sample MNI of 27 is calculated from the adult occipitals and the five sub-adults shown here.

* As there was no duplication of bones within the sub-adult categories, it is assumed that there is only one individual in each sub-adult age range.

A MNI of seven adults was identified from fragments of two pubic symphyses and nine auricular surfaces (left and right hips; Table 1). The former indicate individuals aged 15–24 years (Suchey & Brooks Reference Suchey and Brooks1990) and the latter indicate individuals aged between 25 and 49 years of age (Lovejoy et al. Reference Lovejoy, Meindl, Pryzbeck and Mensforth1985).

Some form of intervertebral disc disease (IVDD) was noted in five cervical, six thoracic, three lumbar and one sacral vertebrae (from one or more individuals), all exhibiting osteophytosis along the body surface margins, suggesting mature or older adults. A fragment of molar tooth root showing severe occlusal wear (down to the tooth root) provides further evidence for an older adult.

The total MNI of 27 is considerably less than might be expected from Hawley's record of 59 cremation burials. The quantity of bone included originally in each burial will have varied (see McKinley Reference McKinley1997). For example, Hawley noted that, while most Aubrey Hole burials “seemed to contain all the bones” (Reference Hawley1928: 158), burials into the fill of the ditch “were chiefly small and insignificant little collections” (Reference Hawley1924: 33).

Analysis of ages reveals a high ratio (4.4:1) of adults (n=22) to sub-adults amongst the MNI of 27. Given the smaller sizes of the elements, sub-adult cremated bone fragments are usually more easily recognised, and should thus be well identified against the mass of fragmented adult bones. Very few sub-adult bone fragments were, however, recovered from the re-buried assemblage from Aubrey Hole 7. The original ratio of adults to sub-adults in Hawley's 59 deposits would probably have been much higher.

The ratio of adults to sub-adults among Stonehenge's cremation deposits does not follow expected mortality curves for pre-industrial populations (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlain2006), where child mortality has been estimated at 30 per cent or more of all deaths (Lewis Reference Lewis2006: 22). The Aubrey Hole 7 ratio is also higher than those recorded for British earlier Neolithic burials of the fourth millennium BC in southern Britain, where the average ratio is 3.9:1 (Smith & Brickley Reference Smith and Brickley2009: 87–90). Thus, there may have been a preference for adults to be buried at Stonehenge as opposed to juveniles, children or infants.

Sex of the individuals in Aubrey Hole 7

Forensic and archaeological advances in analysing non-cremated and cremated IAMs have produced reliable techniques for determining sex by measuring the lateral angle of the internal acoustic canal (Wahl & Graw Reference Wahl and Graw2001; Lynnerup et al. Reference Lynnerup, Schulz, Madelung and Graw2005; Norén et al. Reference Norén, Linnerup, Czarnetzki and Graw2005). This was achieved by taking measurements from CT scans of each of the 24 right and 16 left IAMs from Aubrey Hole 7 (Figure 7). The results from the lateral angles reveal nine males and fourteen females (three are undeterminable). There are potentially some sub-adult IAMs within this assemblage, so these CT-scan results are considered to provide a count for the entire assemblage, not just for adults.

Figure 7. An example of a CT scan's axial slice through a petrous bone (from grid square 355) to measure the lateral angle of the internal auditory meatus.

Biological sex was also determined from the 22 adult occipital bones: nine are identified as male, and five as female. Given the small sample size, it is not possible to say more than that numbers of males and females were roughly equal.

Pathology

The most commonly occurring pathology is IVDD, resulting in changes to the spinal column. Many vertebral bodies exhibit mild to moderate osteophytosis (new bone growth) around their margins, and Schmorl's nodes (indentations) on their surfaces (Rogers & Waldron Reference Rogers and Waldron1995: 20–31). Also noted were changes to the neck of a femur and to the intercondylar ridge of a distal femur, linked to osteoarthritis affecting the synovial joints. These changes are most often the result of advanced age but can also derive from occupation, genetic disposition and a highly calorific diet (Roberts & Cox Reference Roberts and Cox2003: 32).

Periostitis, a non-specific disease affecting the periosteum (connective tissue on the surface of the bones) that results in new bone growth, was noted on fragments of a clavicle, a fibula, a radius and a tibia. Periostitis can be caused by injury, chronic infection or overuse of a particular body part.

The distal fifth of a left femur had a defect in the popliteal fossa on the back of the bone just above the femoral condyles (Figure 8), likely to result from the pulsatile pressure caused by an aneurysm of the popliteal artery (a widening of the femoral artery where it passes through the popliteal fossa). This condition is rare in women but occurs among 1 per cent of men aged 65–80, and was common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries among horsemen, coachmen and young men in physically demanding jobs (Suy Reference Suy2006). This is the first-recorded palaeopathological case of an aneurysm of the popliteal artery from any archaeological assemblage.

Figure 8. A defect in the popliteal fossa on the back of a femur. The defect is oval in shape with its long axis orientated in the long axis of the bone (25.5 × 21.8mm and approximately 10mm in depth); the edges of the lesion are smooth with no evidence of remodelling, and its walls are smooth. It was probably caused by a popliteal aneurysm (photograph: Stuart Laidlaw).

Radiocarbon dating

Although the internal auditory meati provided the largest MNI from Aubrey Hole 7, it was decided to select the occipital bones for destructive sampling for radiocarbon datingbecause of the greater potential of the complex structure of the IAMs to yield future insights into the lives of these individuals buried at Stonehenge. Twenty-one adult/probable-adult occipital bone fragments were dated (one was omitted), along with three sub-adult bone fragments. The foetus and infant bone fragments were omitted because they would have been entirely destroyed by sampling. All samples were submitted to the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU) and samples from six of the 21 adults dated at Oxford were also dated at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC) as part of a quality assurance programme.Five of the six replicate measurements are statistically consistent (Table 2), with only the measurements on sample 225 (OxA-27089 and SUERC-42886) being statistically inconsistent at 95% confidence (T’=5.5; ν=1; T’(5%)=3.8). The measurements on sample 225 are statistically consistent at 99% confidence (T’=5.5; ν=1; T’(1%)=6.6), and thus weighted means of all the replicate determinations have been taken as providing the best estimate of the dates of death of these six individuals.

Table 2. Radiocarbon dates on cremated human remains from Aubrey Hole 7 and adjacent deposit 007.

Previously dated human remains from the third millennium BC at Stonehenge include two fragments of unburnt adult skull from different segments of the ditch (OxA-V-2232-46 & OxA-V-2232-47; Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009: 28–29), and cremated bone from Aubrey Hole 32 (see above) and two contexts in the ditch. One of these ditch contexts (3893) contained 77.4g of cremated bone (McKinley Reference McKinley, Cleal, Walker and Montague1995: 457), from which a fragment of a young/mature adult radius dates to 2570–2360 cal BC (OxA-17958, 3961±29 BP; Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009: 26). The other two cremated specimens, both from ditch context 3898, date to 2920–2870 cal BC (SUERC-42882, 4289±20 BP; combined with OxA-17957, 4271±29 BP); one of these (if not both) is from a young woman aged around 25 years.

Finally, a human tooth from the SPACES project 2008 trench at Stonehenge dates to 2470–2210 cal BC (OxA-18649, 3883±31 BP; Darvill & Wainwright Reference Darvill and Wainwright2009). This has been excluded from this study because it was found immediately below the turf in soil that may not be from Stonehenge (the turf was laid some 20–25 years ago, and may incorporate topsoil from nearby).

The radiocarbon dates from all dated human remains group between 3100 and 2600 cal BC (Figure 9), except for one cremation-related deposit dating to 2570–2360 cal BC (context 3893; OxA-17958) and the Beaker-period inhumation burial (Evans Reference Evans1984) dating to 2400–2140 cal BC (Cleal et al. Reference Cleal, Walker and Montague1995: 532–33). The measurements are not, however, statistically consistent (T’= 1339.4; ν=38.7; T’(5%)= 26; Ward & Wilson Reference Ward and Wilson1978), so they represent more than one burial episode.

Figure 9. Probability distributions of third millennium cal BC dates on cremated and unburnt human remains from Stonehenge. The distributions are the result of simple radiocarbon calibration (Stuiver & Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1993).

Chronological modelling

Bayesian statistical modelling was employed because these radiocarbon dates all come from the same site (Buck et al. Reference Buck, Litton and Smith1992; Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Bronk Ramsey, van der Plicht and Whittle2007). A standard approach to modelling, when dealing with chronological outliers such as ditch context 3893, would be to eliminate them manually from the analysis. This was considered an unsuitable method to apply to this assemblage because the late cremation-related deposits (including burials) in the ditch—“small and insignificant little collections” (Hawley Reference Hawley1928: 157), such as the Beaker-period cremated remains from context 3893—appear to be under-represented or entirely missing from the Aubrey Hole 7 sample. Therefore the chronological outliers from Hawley's ditch contexts are of great significance, especially for the cemetery's end-date.

More useful are trapezoidal models for phases of activity (Lee & Bronk Ramsey Reference Lee and Bronk Ramsey2013) in situations where we expect activity to follow the pattern of a gradual increase, then a period of constant activity and finally a gradual decrease, unlike the assumptions of a uniform model (Buck et al. Reference Buck, Litton and Smith1992). The model shown in Figure 10 uses the trapezoid model of Karlsberg (Reference Karlsberg2006) as implemented in OxCal v4.2 (Lee & Bronk Ramsey Reference Lee and Bronk Ramsey2013).

Figure 10. Probability distributions of dates from Stonehenge's third millennium cal BC burials (trapezium model), excluding the Beaker-period inhumation (Evans Reference Evans1984) dating to 2400–2140 cal BC.

A trapezoid prior model more accurately reflects the uncertainties in processes such as the use of a cremation cemetery: in uniform models there is an abrupt increase from no use to maximum use, while the trapezoid model allows for gradual change. The parameters from the trapezoid model represent the very first and last use, and this model is preferred over others because we do not have the archaeological information to show that there were any abrupt changes a priori.

This model has good overall agreement (Amodel=93) and provides an estimate for the first burial of 3180–2965 cal BC (95% probability: start_of_start; Figure 10) or 3075–2985 cal BC (68% probability). This model estimates that the last burial took place in 2830–2685 cal BC (40% probability: end_of_end; Figure 10) or 2565–2380 cal BC (55% probability) and probably 2825–2760 cal BC (28% probability) or 2550–2465 cal BC (40% probability). The model estimates that burial of cremation deposits took place for 170–715 years (95% probability) and probably 225–345 years (26% probability) or 485–650 years (42% probability).

The development of the cemetery

The date of 2990–2755 cal BC (95% probability; Ditch_constructed; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Darvill, Parker Pearson and Wainwright2012: fig. 6) for the digging of the ditch in Stonehenge's first stage (Darvill et al. Reference Darvill, Marshall, Parker Pearson and Wainwright2012: 1028) accords well with the dates of the earliest cremation burials. The use of Stonehenge as a cemetery probably ended with the Beaker-period inhumation burial after 2140 cal BC, by which time Stonehenge stages 2 and 3 were completed (Darvill et al. Reference Darvill, Marshall, Parker Pearson and Wainwright2012: 1026). Thus, burials began at Stonehenge before, and continued beyond, the stage when the sarsen trilithons and circle were erected.

The re-cutting of the ditch after 2450–2230 cal BC (Darvill et al. Reference Darvill, Marshall, Parker Pearson and Wainwright2012: 1038) means that all cremation-related deposits from its upper fills—as many as 15 of Hawley's “small and insignificant little collections” (Reference Hawley1928: 157)—probably date to after 2450 cal BC. Yet only context 3893 has been radiocarbon-dated to this period (Beaker Age), presumably because none of these 15 deposits from the ditch's upper fills (25 per cent of Hawley's 59 deposits re-buried in Aubrey Hole 7) was substantial enough to include identifiable occipital bones.

Hawley noted that, in contrast, most of the burials in Aubrey Holes “seemed to contain all the bones” (Reference Hawley1928: 158), so the dated occipital bones from Aubrey Hole 7 therefore probably provide a representative sample of the individuals originally buried in these pits. Some, such as the adult in the packing of Aubrey Hole 32, were buried at the time of the digging-out of the pit circle. Hawley (Reference Hawley1923: 17) considered that others were buried while a pillar stood in the hole: he remarks that the upper edges of many Aubrey Holes had bowl-shaped recesses for containing cremated remains, indicating that interments were made against standing stones after they were erected. He also records one cremation-related deposit that was placed in its Aubrey Hole (24) after the standing stone had been withdrawn (Hawley Reference Hawley1921: 31; he mis-numbered this hole 21). The hypothesis that human cremated remains were introduced into the Aubrey Holes when bluestones were erected within them during stage 1 of Stonehenge, and subsequently (until the bluestones were removed for constructing stage 2), is supported by the date range for the occipital bones.

The chronological distribution of age and sex within the cemetery reveals that men and women were buried at Stonehenge from its inception, and that both sexes continued to be buried over the following centuries. This lack of sexual bias is of interest when considering the probable higher social status of those buried, and when compared with higher ratios of adult males to females in earlier Neolithic tombs in southern Britain (Smith & Brickley Reference Smith and Brickley2009: 88–90). Stonehenge was a cemetery for a selected group of people who were treated separately from the rest of the population. It was surely a powerful, prestigious site in the Neolithic period, with burial there being a testament to a culture's commemoration of the chosen dead.

Cremation practices in Late Neolithic Britain (c. 3000–2500 BC)

There are very few human remains in Britain dated to the early and mid third millennium cal BC, a period when the rite of inhumation burial seems, by and large, not to have been practised (see Healy Reference Healy, Allen, Gardiner and Sheridan2012 for rare exceptions). Cremation burials that are probably of this date are known from a growing number of sites (Parker Pearson et al. Reference Parker Pearson, Chamberlain, Jay, Marshall, Pollard, Richards, Thomas, Tilley and Welham2009: 34–36). Stonehenge is the largest-known cemetery from this period, with small cemeteries or groups of burials excavated from former stone circles or stone settings at Forteviot (Noble & Brophy Reference Noble and Brophy2011), Balbirnie (Gibson Reference Gibson2010), Llandygai (formerly Llandegai; Lynch & Musson Reference Lynch and Musson2004) and Cairnpapple (Sheridan et al. Reference Sheridan, Bradley and Schulting2009: 214), and from circular enclosures at Imperial College Sports Ground (Barclay et al. Reference Barclay, Beacan, Bradley, Chaffey, Challinor, McKinley, Powell and Marshall2009) and Dorchester-on-Thames (Atkinson et al. Reference Atkinson, Piggott and Sandars1951). Cremation burials that may date to this period have also been found at Flagstones (Healy Reference Healy, Smith, Healy, Allen, Morris, Barnes and Woodward1997), Barford (Oswald Reference Oswald1969), Duggleby Howe (Mortimer Reference Mortimer1905) and West Stow (West Reference West1990).

The growing recognition of the extent and number of Late Neolithic cremation burials and cemeteries across Britain has largely resulted from the ability to radiocarbon-date cremated bone in unaccompanied cremation burials. It is now possible to recognise in Britain a major phase, lasting half a millennium, during which cremation was practised almost exclusively. This followed the collective and individual inhumation rites of the Early and Middle Neolithic but occurred prior to the inhumation rites of the Beaker period.

With so few cremation burials independently dated, let alone known from this period, the Stonehenge assemblage is the largest and most important in Britain, regardless of the significance of the site itself. Although scattered examples of cremation burial are recorded in the British Early Neolithic (Smith & Brickley Reference Smith and Brickley2009: 57–60; Fowler Reference Fowler2010: 10–11), Stonehenge and other Late Neolithic sites mentioned above are the first-known cremation cemeteries in Britain.

In contrast, the evidence from Ireland shows a more continuous and extensive tradition of cremation burial stretching back to the first half of the fourth millennium BC (e.g. O'Sullivan Reference O'Sullivan2005; Bergh & Hensey Reference Bergh and Hensey2013; Cooney Reference Cooney, Kuijt, Quinn and Cooney2014). It is possible that the widespread adoption of cremation in Late Neolithic Britain may have been influenced by mortuary practices in Ireland.

Conclusion

Our research shows that Stonehenge was used as a cremation cemetery for mostly adult men and women for around five centuries, during and between its first two main stages of construction. In its first stage, many burials were placed within and beside the Aubrey Holes. As these are believed to have contained bluestones, there seems to have been a direct relationship between particular deceased individuals and standing stones.

Human remains continued to be buried during and after Stonehenge's second stage, demonstrating its continuing association with the dead. Most of these later burials appear, however, to have been placed in the ditch around the monument's periphery, leaving the stones, now grouped in the centre of the site, distant from the human remains.

Stonehenge changed from being a stone circle for specific dead individuals linked to particular stones, to one more diffusely associated with the collectivity of increasingly long-dead ancestors buried there. This is consistent with the interpretation of Stonehenge's stage 2 as a domain of the eternal ancestors, metaphorically embodied in stone (Parker Pearson & Ramilisonina Reference Parker Pearson1998; Parker Pearson 2012).

Technical note

The calibrated date ranges for the radiocarbon samples were calculated using the maximum intercept method (Stuiver & Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1986), and are quoted with end points rounded outwards to 10 years, or 5 years if the error is <25 years. The probability distributions of the calibrated dates, calculated using the probability method (Stuiver & Reimer Reference Stuiver and Reimer1993), are shown in Figures 9 & 10. They have been calculated using OxCal v4.1.7 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) and the internationally agreed atmospheric calibration dataset for the northern hemisphere, IntCal09 (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Baillie, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Burr, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Hajdas, Heaton, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, McCormac, Manning, Reimer, Remmele, Richards, Southon, Talamo, Taylor, Turney, van der Plicht and Weyhenmeyer2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Amanda Chadburn for helping us to meet English Heritage's requirements for sampling for radiocarbon dating, and David Sugden and Charles Romanowski of the Royal Hallamshire Hospital for scanning and measuring of petrous canals. Useful comments on the manuscript were provided by Duncan Garrow and Derek Hamilton. Funding was provided by the AHRC (Feeding Stonehenge Project; AH/H000879/1) and Oxford Scientific Films.