Introduction

Most Higher Education (HE) students in Ireland are between 18 and 24 years old. This is the time in a person’s life when they are most likely to develop a mental health disorder (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Amminger, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Alonso, Lee and Ustün2007; Cuijpers et al., Reference Cuijpers, Auerbach, Benjet, Bruffaerts, Ebert, Karyotaki and Kessler2019), which can affect them well beyond these young adult years (Erskine et al., Reference Erskine, Moffitt, Copeland, Costello, Ferrari, Patton, Degenhardt, Vos, Whiteford and Scott2015). Student mental health and well-being in HE are issues of concern, as demonstrated by this special issue, the recent funding initiatives by the Minister for Further and Higher Education, Research, Innovation and Science, and recent national reports (Dooley et al., Reference Dooley, O’Connor, Fitzgerald and O’Reilly2019; Union of Students in Ireland, 2019; Fox et al., Reference Fox, Byrne and Surdey2020). In Ireland, the Association for Higher Education Access & Disability in 2017/2018 (AHEAD, 2019) noted that the number of students with mental health disorders was increasing twice as fast as other groups of students with disabilities. Within Higher Education Institutions (HEIs), while a number of services provide mental health support to students (e.g., campus GP), the student counselling services (SCSs) are the largest provider of student mental health support, seeing an estimated 7% of the student population (approximately 16,500 students of 237,000 HE students) (PCHEI, 2021a).

Hill et al. (Reference Hill, Farrelly, Clarke and Cannon2020) call for an evidence-based approach to student mental health in Irish HEIs. Furthermore, there is a call for the collection of standardised data from HE SCSs (Barkham et al., Reference Barkham, Broglia, Dufour, Fudge, Knowles, Percy, Turner and Williams2019; Hughes & Spanner, Reference Hughes and Spanner2019; Broglia et al., Reference Broglia, Ryan, Williams, Fudge, Knowles, Turner, Dufour, Percy and Barkham2021). Standardised data are required for the identification of trends and effective interventions on a sectoral level. One approach to the collection of standardised data is through an active database that collects non-aggregate data regularly from HE SCSs. An example of this is the Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH) in Penn State University. CCMH is an established research centre and Practice-Research Network (PRN) for SCSs. CCMH started as a ‘grass-roots’ movement with a small budget before formally being founded in 2005 (McAleavey et al., Reference McAleavey, Lockard, Castonguay, Hayes and Benjamin2015). Initially, the centre had approximately 35 SCS members as well as the support of the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors, and the Counseling and Psychological Services and Student Affairs in Penn State University. In 2006, CCMH had its inaugural conference where 50 SCSs came together to compare their data collection (McAleavey et al., Reference McAleavey, Lockard, Castonguay, Hayes and Benjamin2015). Between them, the SCSs were using 35 different self-report outcome measures. Later, following a review process, the Counseling Centre Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPs) was chosen as their sole outcome measure based on it being multi-dimensional, psychometrically sound and could be made freely available to SCS members. In addition, in 2006, CCMH started its collaboration with Titanium Schedule, an electronic management system company. This relationship has proven highly productive and a cornerstone of their database (McAleavey et al., Reference McAleavey, Lockard, Castonguay, Hayes and Benjamin2015). In 2007, CCMH finalised a national standardised data set for its members, and in 2009 CCMH produced its first annual report based on data from 66 SCSs. For the 2019/2020 academic year, 153 HE SCSs provided data from 185,440 students (CCMH, 2020). While their recent annual reports show mental health trends, client demographic information, and service centre information, they also contain a section addressing some aspect of service that practitioners want information on. One key to the success of CCMH is their PRN, their network is built on the co-operation and collaboration between practitioners and researchers. This allows for research questions to be drawn directly from practice and for the research to feed back into practice. Similar to CCMH, the University of Wisconsin System Counseling Impact Assessment Project collects and analyses data from its SCS members.

In the UK, the Student Counselling Outcomes Research and Evaluation (SCORE) Consortium in collaboration with the British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP) and the United Kingdom Council for Psychotherapy (UKCP) is currently developing a database for the HE SCSs (SCORE, 2021). Furthermore, BACP and UKCP provide financial support and in-kind contributions of researchers’ time to the SCORE Consortium. The initial pilot activities for the development of this database began in October 2018. Their activities include raising awareness on the need to collect standardised data (Barkham et al., Reference Barkham, Broglia, Dufour, Fudge, Knowles, Percy, Turner and Williams2019), collecting and analysing SCS data (Broglia et al., Reference Broglia, Ryan, Williams, Fudge, Knowles, Turner, Dufour, Percy and Barkham2021), encouraging the use of clinical outcome measures in SCSs (Broglia et al., Reference Broglia, Ryan, Williams, Fudge, Knowles, Turner, Dufour, Percy and Barkham2021), and developing a PRN (SCORE, 2021). Their recent study (Broglia et al., Reference Broglia, Ryan, Williams, Fudge, Knowles, Turner, Dufour, Percy and Barkham2021), which represents the first step of their national data set and a proof of concept, examines data collected from four counselling services who use two different outcome measures (CCAPs and CORE Outcome Measure (CORE-OM)) and two different electronic management systems (Titanium Schedule and CORE Net). Also, in France, there is a call to collect national statistics in the area of student mental health (Nightline France, 2020).

In Ireland, while this ongoing project on developing a national SCS Database is novel, there are examples of national health databases in practice, for example, the Irish Maternity Indicator System (McMahon et al., Reference McMahon, McGrane, McKenna and Turner2020). Alternative sources of data from SCSs include annual surveys, for example, those conducted by the Association for University and College Counseling Center Directors (Gorman et al., Reference Gorman, Bruns, Chin, Fitzpatrick, Koenig, LeViness and Sokolowski2020) and the Australian and New Zealand Student Services Association (Andrews, Reference Andrews2019).

This paper details the development of the Irish national SCS Database and identifies those involved in supporting it under the following headings 1) Origin of the SCS Database, 2) Background Research, 3) Standardisation of the Data, 4) General Data Protection Regulation, 5) Development of the Database, 6) Moving forward, and 7) Reflections on Developing the SCS Database.

Origin of the SCS database

PCHEI was founded in 1994 by student counsellors from various HEIs (PCHEI, 2021b). As primary providers of embedded mental health support to students, PCHEI saw the importance of gathering aggregate data on how and why students use SCSs. Since 1996, PCHEI has used standardised categories for annual reporting of students’ presenting problems and their engagement with SCSs. PCHEI now includes SCSs from the vast majority of the HEIs in the Republic of Ireland – comprising services available to over 200,000 students. As PCHEI has evolved over the past 25 years, international examples have helped improve its data collection standards. Data collection now includes standardised measures of student attendance, types of counselling appointments, presenting issues, basic demographics, and counselling’s impact on academic outcomes. These data are first aggregated locally by each service for the preceding academic year and then combined to form the PCHEI annual statistics report. The amount of data contributed to the annual survey is impacted by SCSs’ data management systems (e.g., electronic management system versus pen and paper).

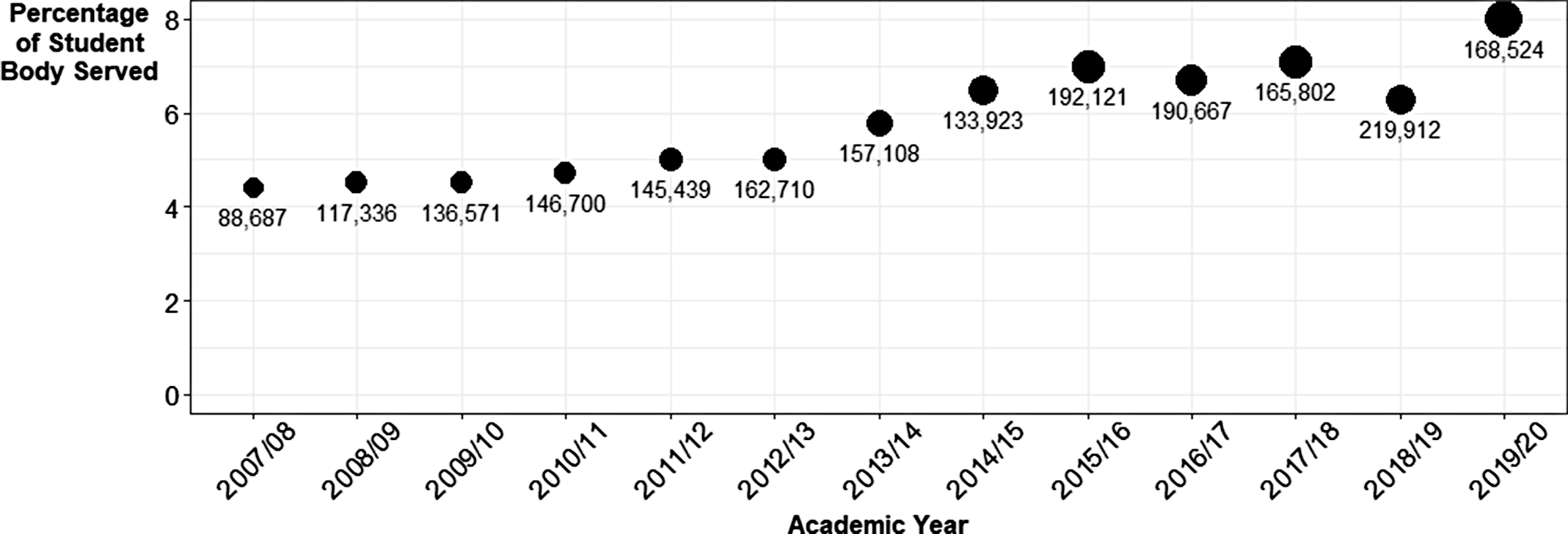

The PCHEI annual statistics (PCHEI, 2021a) help to track trends in HE student mental health. For example, students attending SCSs grew from 3863 (∼4% of all students) in 2007–2008 to 13,877 (∼6% of all students) in 2018–2019 (see Fig. 1). Between 2008 and 2018, the most prevalent presenting issues for which students seek help have consistently been anxiety (rising from 19% to 50% of clients) and depression (rising from 17% to 35% of clients). While such metrics are useful, their aggregate sources make more meaningful analysis difficult – for example, it is not possible to examine the overlapping nature of presenting issues, or the relationship between various demographic variables (e.g., gender, age, race, or cultural background) and student mental health. Developing a more sophisticated system for analysing the large amounts of non-aggregate data on student mental health would be a valuable tool for PCHEI planning and service development.

Fig. 1. Percentage of student population served by PCHEI between 2007/08 and 2019/20 with total HEI enrolment figures for PCHEI members’ reporting

The Higher Education Authority (HEA) has a statutory responsibility for the effective governance and regulation of HEIs (HEA, 2021a) who are in receipt of public funding (n = 24; HEA, 2021b). In 2018, the HEA Innovation and Transformation fund was announced to help support transformational ideas across HEIs in Ireland. In 2019, as part of this funding call, the HEA funded the project entitled, ‘Student support services’ retention and engagement strategy: Consolidation of best practice, centralisation of data and innovation in student experience’, or the 3SET project (3SET, 2021). Within 3SET, there are three complimentary work packages. These work packages are on the development of a flexible peer support programme (led by Trinity College Dublin), suicide prevention and shared resources for SCSs (led by Athlone Institute of Technology), and the establishment of a national database for Irish HE SCSs (led by University College Dublin (UCD)). The co-authors of this paper commenced working on the SCS database project together in June 2019 with the initial stage involving background research. The authors are working closely with the PCHEI executive and members to develop the SCS Database, with the third author being the PCHEI Statistics Liaison Officer. The three overarching and interconnecting aims of the UCD work package are

-

Creation of a national database for SCSs in Irish HEIs,

-

Establishment of a Practice-Research Network, and

-

To support services in using outcome measures for routine evaluation.

Background research

The first stage of the project focused on developing connections with relevant parties and knowledge acquisition; commencing with a review of Irish HE SCSs’ websites and any relevant institutional reports. A scoping literature review was performed in the areas of data collection in SCSs, the provision of mental health support at HE, and the mental health of young adults. However, there was a clear gap in the literature in regard to the Irish context. To understand the Irish context, ethics approval was sought and received from the UCD Research Ethics Committee to interview personnel who were connected with HE services providing student (mental health) support. The initial interviews were with UCD student services (a Chaplain, a Disability Officer, and two Student Advisors). From this, the authors learnt about data collection in the wider context of student services and part of the relationship between SCSs and other student services. Between October 2019 and February 2020, interviews were conducted with representatives of 22 SCSs (for the purpose of these interviews the HEI structure is considered prior to the introduction of Technological Universities as SCSs had not merged data collection systems at the interview stage). This consisted of 28 interview participants including the Heads of SCSs, student counsellors, administrators for SCSs, and Heads of Student Services. The aims of these interviews were to understand the range of support HE SCSs provide, what data are collected and how they are collected, and to listen to practitioners’ opinions towards the national SCS Database. They emphasised the autonomy and unique development of each SCS. When conducting the interviews, the authors requested from SCSs their intake forms, confidentiality agreements, and feedback forms. The interviews have been highly informative for feeding into the design of the database, the standardisation of the data, and developing a rapport between the authors and the SCSs.

Early on, a number of key decisions in establishing the SCS Database arose. For example, whether to establish the database for a small number of HEIs and then expand to other HEIs (similar to the approach by CCMH and SCORE) or to potentially allow every HE SCS to be involved in the SCS Database from the beginning. Considering the small size of Ireland, the sense of a counselling community established through PCHEI, the independence of HE SCSs, and the length of the HEA funding period, the latter approach was chosen. A second decision that was raised early was in relation to SCSs’ electronic management systems. CCMH’s technological partnership with Titanium Software has been a beneficial relationship for both parties (McAleavey et al., Reference McAleavey, Lockard, Castonguay, Hayes and Benjamin2015). In 2019/2020, Ireland’s SCSs were using a range of data management systems including paper and pen, Microsoft Office, Yellow Schedule, Helix Practice Manager, HealthOne, CORE-Net, and Titanium Schedule. Consideration was given as to whether to limit the SCS Database to those who had a specific system or to allow for the range of management systems. The decision was taken to work with the range of systems that SCSs had. In addition to regular contact with PCHEI, expert individuals who are involved in national and international health databases (CCMH, SCORE, UW System, and IMIS) were consulted.

Standardisation of the data

Significant challenges exist in collecting standardised data across SCSs; a balance needs to be achieved in regard to the amount of data being collected. Data should be purposively collected for the benefit of SCS users and rich enough to provide meaningful insight into student mental health. However, requesting large volumes of data from clients of SCSs can be overwhelming for the individuals involved and can potentially be time consuming for SCS staff. Obtaining agreement on what constitutes a standardised data set is an essential step in developing the SCS database (McAleavey et al., Reference McAleavey, Lockard, Castonguay, Hayes and Benjamin2015). Based on the existing literature and the prior data collection completed by PCHEI, the team identified several categories of data that are applicable for a standardised national SCS data set. These are student demographic information, routine outcome measures, presenting/emerging issues, and data on the roles and functions of SCSs. The Australian and New Zealand Student Services Association Pty Ltd, in their survey of SCSs (Andrews, Reference Andrews2019), found that in the majority of SCSs, 60–79% of staff time is spent delivering individual counselling. Consequently, upwards to 40% of staff time is spent on other activities, for example, group therapy, crisis interventions, consultation with HE staff, workshops, programmes targeting specific student cohorts, supervision, and report writing. Therefore, collecting data on the roles and functions of SCSs is essential for presenting a comprehensive view of the services provided by SCSs.

McAleavey et al. (Reference McAleavey, Lockard, Castonguay, Hayes and Benjamin2015) emphasised the importance of establishing a shared sense of community throughout the process of developing a SCS database, including during the process of standardisation. In November 2019, as part of the PCHEI Autumn training day, a seminar was conducted on the work package progress. The main aspects were informing student counsellors on the progress made, clarifying any identified misconceptions concerning the standardised dataset and database, and involving the student counsellors in discussion around categorisation of clients’ presenting issues.

Standardisation, apart from agreeing on which variables to include, also includes standardising the response categories for each variable. For example, while gender was being collected across SCSs, the way in which gender was being collected varied greatly from male/female/non-binary to an open response option. The first step towards a standardised data set was to review variables currently being collected by SCSs. This meant that the standardised data set was situated in SCSs’ existing data collection and counsellors could make connections between the two. To do this, the collected intake forms and feedback forms from SCSs were analysed alongside the variables from PCHEI’s annual data collection and from other SCS data collections, for example, CCMH. Initially, all variables that were being collected were listed from every identified source in one document. Each variable was discussed, and sometimes alternative variables were suggested. In addition to looking at the responses already used by SCSs and other SCS databases, other categorisations were examined including those used by the HEA (HEA, 2021c), the Central Statistics Office (CSO, 2021), and the My World 2 survey (Dooley et al., Reference Dooley, O’Connor, Fitzgerald and O’Reilly2019). The aims of the discussions were to identify beneficial variables and to reduce the number of variables to a potential standardised data set. This work led to the development of the standardised data set manual version one (SDS V1).

In May 2020, at the PCHEI annual conference, the team presented the SDS V1 to 74 participants (3SET, 2021). In preparation for the webinar, the SDS V1 was forwarded to student counsellors through the PCHEI network along with an excel file showing one year’s data collection and a mock annual report based on the SDS V1. The aims of the webinar were to present the SDS V1 and receive feedback upon it, answer counsellors’ questions about the project, inform student counsellors of the next steps in the development of the database, and consult with student counsellors on more controversial variables, for example, risk and disabilities. The final aim was accomplished through break-out group discussions. Individual feedback was sought through a Qualtrics survey post-webinar (n = 39). The feedback was used to produce SDS V2 (see Table 1). Full documentation is available online (SCS Database, 2021a). In addition, a presenting issues manual was developed (SDS Database, 2021b). This includes definitions for each category (see Table 2) and details on standardised collection of the presenting issues. Comparatively, building on their prior research (e.g., Broglia et al., Reference Broglia, Millings and Barkham2018), the SCORE Consortium invited relevant parties to engage in their standardisation process through focus groups and a survey (SCORE, 2021).

Table 1. Standardised dataset – client data variables

Table 2. Categories of presenting issues collected by the SCS Database

General data protection regulation

Data protection, and the laws concerning it, is an area of particular relevance when establishing a database in a European Union country. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), introduced in May 2018, is a legal framework that sets guidelines for the collection and processing of personal information from individuals who live in the European Union (European Parliament and Council of European Union, 2016). In Ireland, GDPR builds on the pre-existing Data Protection Acts of 1988 and 2003. From the beginning of the project, UCD’s Data Protection Officer (DPO) was consulted on the development of the database. In accordance with GDPR, the processing of personal data must be conducted under one or more of the six legal bases (Article 6 of GDPR). After consultation with HE DPOs and consideration of the stakeholders, the legal basis decided upon for the SCS Database was a public interest basis. Additionally, mental health data are considered as special category data under GDPR and require additional consideration (Article 9 of GDPR), for example, explicit consent under Article 9 acts as a safeguard for the data.

As each HEI, and the SCS within, operates as an autonomous entity, during the establishment of the database it was important to liaise with each institute’s DPO. To help with this process, a short overview of the project was created that outlined the key GDPR points of the SCS Database. The SCSs were encouraged to send this document to their DPO to initiate a dialogue. The research team would then address concerns raised and provide any documentation requested by the DPOs, for example, the Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) for the SCS Database. As part of the due diligence of the project, a DPIA was undertaken. According to the UCD DPIA (UCD, 2019, p. 1), a ‘DPIA has three major functions:

-

1) It helps to identify any potential high risks to data privacy, when planning new or revising existing projects, and to design actions to mitigate these risks.

-

2) It is a useful tool to help organisations demonstrate their compliance with data protection law.

-

3) DPIAs help with implementing Privacy by Design’.

A DPIA is considered as a living document and should be updated and maintained throughout the life of any data project. In addition to the DPIA, a Data Protection Policy for client data, a Data Protection Policy for counsellor data, and a Privacy Notice were created to explain how the SCS Database complies with different aspects of GDPR (3SET, 2021).

Development of the database

The SCS Database is being made possible through the collaboration of many parties. Apart from the UCD DPO, advice and support has been sought from a number of UCD departments including Legal, the Research Ethics Committee, and Research IT. For example, the Legal department was integral in drawing up data sharing agreements. As each HEI is an autonomous entity, how to approach receiving ethical approval was of particular concern. In the case of CCMH, each contributing SCS seeks ethical approval or exemption from its own institution ethics committee. Advice was sought on the best approach for the SCS Database from the UCD Research Ethics Committee. For the SCS Database, similar to CCMH, each contributing SCS is required to approach their institution ethics committee. Supporting materials were created to help SCSs in completing ethics applications. Similarly, the SCORE Consortium has tried to streamline the ethics process for SCSs (Broglia et al., Reference Broglia, Ryan, Williams, Fudge, Knowles, Turner, Dufour, Percy and Barkham2021). In addition, one overall ethics application is required for the SCS Database (through the UCD ethics committee). UCD Research IT provided support through their technical advice and expertise on the security measures for the SCS Database. As mentioned, Ireland’s SCSs use a range of electronic management systems, not dissimilar to the UK SCSs (Broglia et al., Reference Broglia, Ryan, Williams, Fudge, Knowles, Turner, Dufour, Percy and Barkham2021). Following a quotation process, Cloudtree, a health database management company was hired to create a database that accommodates the range of systems used in Irish HE SCSs. When choosing a suitable company, GDPR compliance and security were core concerns. Given the confidentiality concerns raised by student counsellors and DPOs, the database has been developed to not only protect the confidentiality of students but also to allow each SCS, and their HEI, to remain anonymous.

While the paragraph above outlines the support received within UCD, the development of the SCS Database has been supported nationally (see Fig. 2). Support was received from student counsellors, Heads of SCSs (as a group and individually), and PCHEI. In addition, for each SCS, their ethics committee, DPO, SCS line manager, and Registrar (or equivalent) have been approached in regard to the SCS Database. An important aspect of the approach taken is facilitating conversation around the SCS Database. This includes incorporating ideas and addressing any concerns raised as early as possible. Without the support and collaboration of all parties, the SCS Database is not possible. Throughout the project, there has been regular contact between the research team and PCHEI executive members, in particular the Chairperson. This has required distributing project materials to the PCHEI membership on behalf of the SCS Database team, arranging regular webinars, providing input into the development of the database and establishing a Memorandum of Understanding between PCHEI and the SCS Database. Apart from PCHEI, the research team has received support from a group of counsellors known as the ‘CORE Group’. The CORE Group are a number of SCSs who currently use or are acquiring CORE Net and are aligning aspects of their CORE Net systems, including aligning data collection to the standardised data set.

Fig. 2. Network diagram of the parties involved in developing the SCS Database

Moving forward

The SCS Database is still in its development stage. The next steps involve receiving input from students as key stakeholders, developing the PRN, and completing an initial pilot round of data collection (with the target being June 2022). The data, once collected, will be analysed and presented to the PCHEI network and SCSs. PCHEI will provide context to the data. The data collection process will then be reviewed for subsequent rounds of data collection. This will include removing any redundant variables and streamlining the collection process. While not in the first round of data collection, the SCS Database will collect outcome measure data. An additional aim is to support services in using outcome measures for routine evaluation. To this end, a scoping literature review of routine outcome measures used by SCSs internationally was conducted, followed by a SWOT analysis of the identified measures. From the interviews conducted with SCSs, similar to the UK (Broglia et al., Reference Broglia, Millings and Barkham2018), it was apparent that the outcome measures used by services varied (e.g., CORE-OM, CCAPS, BSI, and no measure) and were impacted by their choice of electronic management system. The routine evaluation measures being considered for inclusion in the SCS Database are CORE-OM/CORE-10, CCAPs-34, Audit, and K-10.

The long-term sustainability of the national SCS Database, and its complementary PRN, is of paramount importance with the essential resources of time and financial support key. CCMH has received revenue from a range of sources (McAleavey et al., Reference McAleavey, Lockard, Castonguay, Hayes and Benjamin2015): donations, membership fees, data access fees, and grants. Funding from the HEA for 3SET is due to finish in June 2022. However, in an effort to ensure the sustainability of the project, the MoU between PCHEI and UCD has been established for five years. Similar to CCMH, the future funding for the SCS Database will likely come from multiple sources. Ideally, a long-term source of funding through a national body (e.g., research funding agency or HE organisation) should be secured. With the end of this phase of development for the database, there will be the introduction of a new governance structure. This will consist of a Steering Committee with a Research Sub-Committee and Database Working Group. The Database Working Group will be responsible for the day-to-day operations of the SCS Database including annual reports. The Steering Committee will direct the long-term agenda of the SCS Database and review the SCS Database policies with special consideration being given to compliance with GDPR and security. The Research Sub-Committee will be responsible for reviewing and approving applications to access the data for student mental health research. In addition to a transparent governance structure, clear communication of statistics from the SCS Database will be essential as data can be, and is, easily misinterpreted. Data if misused can lead to sensationalised articles (Chen & Lawrie, Reference Chen and Lawrie2017) and a mistrust between researchers and practitioners.

Long-term, the SCS Database will support a PRN whereby practitioners and researchers will collaborate on practice-driven research. Part of this will involve practitioners proposing areas of clinical interest or research questions to work upon and collaborating with researchers to the extent they wish, or their professional work allows. CCMH conducted a survey with practitioners (n = 627) and found that the types of psychotherapy research that practitioners deem most important or valuable are those related to the process of counselling, high risk behaviours and disorders, and the effectiveness of counselling (Youn et al., Reference Youn, Xiao, McAleavey, Scofield, Pedersen, Castonguay, Hayes and Locke2019). To sustain the PRN, the research conducted will need to directly benefit practitioners and their clients.

Reflections on developing the SCS database

One external factor that has impacted the project is COVID-19. The interview phase of the project concluded with the first national COVID-19 lockdown in Ireland. As part of this, SCSs had to pivot to tele-health services with limited face-to-face services. This increased the workload for SCSs which in turn impacted the resources services could commit to the SCS Database. Owing to COVID-19 restrictions, there has been a substantial increase in communication apps, for example, Microsoft Teams and Zoom. This has allowed for easier communication with SCSs (who are demographically spread across the Republic of Ireland).

Reflecting on the approach taken, there are some topics that would have benefitted from further elaboration for practitioners earlier in the project. For example, the shift from aggregate data, the format of PCHEI’s annual survey, to the SCS Database collecting non-aggregate data. With this shift, the concerns of confidentiality and data protection need to be addressed, but also detailed explanations provided around the potential benefits of collecting non-aggregate data (e.g., identification of trends in sub-groups and foundation of a PRN).

Creation of a national database and PRN is not possible without the collaboration and support of many parties. McAleavey et al. (Reference McAleavey, Lockard, Castonguay, Hayes and Benjamin2015, p. 149) expressed this aptly by the statement ‘It takes vision, time, and a village’. Key to the success of a collaboration such as this is the early involvement of, and continued communication between, parties. Development of the SCS Database is an ongoing process, but the expected outcomes include the following:

-

National statistics to inform SCSs planning,

-

Identification of student mental health trends,

-

Comparison of the Irish sector internationally for the purpose of best practice,

-

Establishment of a data set that can be used for evidence-based research on student mental health, and

-

National data for funding applications

Foremost, students’ data are at the centre of the SCS Database and the findings from the database must be disseminated to support them and help improve services.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank everyone involved in developing the SCS database including PCHEI, HE student counsellors, Heads of SCSs and Student Services, SCS administrators, Registrars, DPOs, Legal departments, Research Ethics Committees, and UCD IT Research.

Conflict of interest

Author [EH] has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Author [ZTF] has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Author [CR] has no conflicts of interest to disclose. Author [BD] has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committee on human experimentation with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The authors assert that ethical approval for publication of this perspective piece has been provided by their local Research Ethics Committee.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Higher Education Authority Innovation and Transformation 2018 funding call under the project entitled: ‘Student support services’ retention and engagement strategy: consolidation of best practice, centralisation of data and innovation in student experience’.