In the United States, rates of homicide involving “intimate partners”—spouses, ex-spouses, boyfriends, girlfriends—have declined substantially over the past 25 years. Public awareness of and policy responses to domestic violence have increased during the same period. The coincidence of the two trends leads naturally to the question of their relationship: To what extent has the social response to domestic violence contributed to the decline in intimate-partner homicide? Research evidence addressing that question is highly limited, but the few existing studies suggest that domestic violence resources and policies such as hotlines, shelters, and legal advocacy programs may be associated with lower rates of intimate-partner homicide, net of other influences (Reference Browne and WilliamsBrowne & Williams 1989; Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld 1999).Footnote 1

In this article, we address the relationship between intimate-partner homicide and domestic violence resources for a larger number of places over a longer period of time and with a considerably richer set of outcome and resource measures than used in previous research. Building on the research by Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, and Rosenfeld (1999), we interpret that relationship in terms of the exposure-reducing potential of domestic violence resources. Simply put, those policies, programs, and services that effectively reduce contact between intimate partners reduce the opportunity for abuse and violence. However, we also assess the alternative possibility that, under certain conditions, domestic violence resources provoke a retaliation effect. Such an effect might occur, for example, if a protection order or other legal intervention directed at an abusive partner increased the level of stress or conflict in the relationship without effectively reducing victim exposure. We evaluate the exposure-reducing and retaliation effects of a broad range of domestic violence resources on levels of heterosexual intimate-partner homicide by victim sex, race, and marital relationship to the offender for 48 large U.S. cities between 1976 and 1996. Further, because we anticipate that other factors can affect the exposure between violent intimates, we control for changes in marriage and divorce rates, women's status, and other time- and place-varying influences.

Contrasting Trends

The growth in domestic violence resources in the United States occurred during a period of declining intimate-partner homicide. The coincidence of the contrasting trends in intimate-partner homicide and social response is especially notable because the overall rate of homicide is trendless during the same period.Footnote 2 The general decline in intimate-partner homicide varies substantially by victim sex, race, and marital relationship to the offender. Larger decreases have occurred for males, African Americans, and married victims (including ex-spouses) than for females, whites, and unmarried intimates (Reference Greenfield, Rand and CravenGreenfield et al. 1998; Reference Browne and WilliamsRosenfeld 2000; Reference Browne, Williams, Dutton, Smith and ZahnBrowne & Williams 1993; Browne, Williams, & Dutton 1999). The intimate-partner homicide victimization rate for married 20- to 44-year-old African-American men dropped by an astonishing 87%, from 18.4 to 2.4 per 100,000, between 1976 and 1996. The differing time trends by victim type highlight the importance of assessing the separate effects of domestic violence resources by victim sex, race, and marital status.Footnote 3 Although age is also an important factor, data sparseness precludes age-specific analyses.

Domestic violence policies, services, and programs in the United States have expanded dramatically since the early 1970s when the battered women's movement began pressing for a social response to the needs of women abused by their spouses (Reference SchechterSchechter 1982).Footnote 4 The movement prompted a redefinition of domestic violence from a private matter to be settled within the family whenever possible to a category of criminal offense meriting special public attention. Policymakers responded with enhanced criminal justice sanctions, specialized procedures, and targeted services to accommodate the special needs of victims who are intimately involved with their abusers.

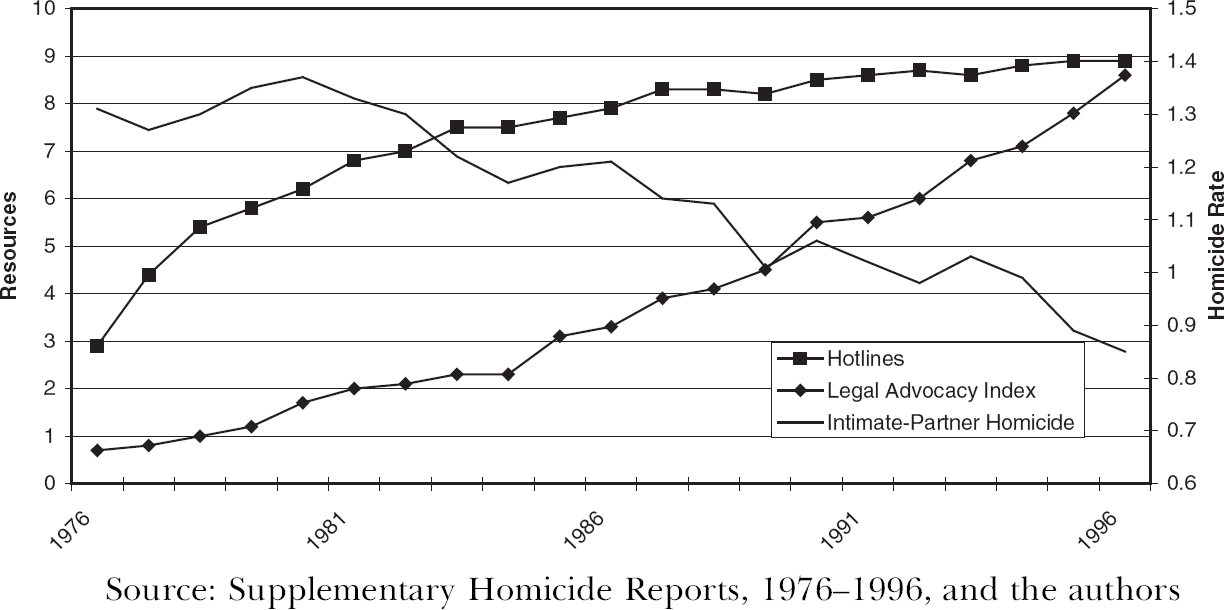

As examples, Figure 1 displays the growth in domestic violence hotlines and legal advocacy programs in 49 large U.S. cities between 1976 and 1996.Footnote 5 The two trends can be viewed as adoption rates for each of the services. Although the growth patterns differ somewhat across the two services, both exhibit pronounced growth over the period, while the intimate-partner homicide rate declined. The legal advocacy index increased nine-fold, with especially rapid growth after the mid-1980s. The adoption rate for hotlines increased sharply in the late 1970s and then flattened out between eight and nine per million women after the late 1980s. The intimate-partner homicide rate, by contrast, dropped to roughly 0.9 from 1.3 victims per 100,000, or by about 30%. The intimate-partner homicide rate is denominated by the population between the ages of 20 and 44, the age category in which intimate homicides are heavily concentrated. (The data are from the Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHR) (http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs/homicide.)

Figure 1. U.S. intimate-partner homicide rates and domestic violence services.

Although domestic violence resources are intended to curb intimate violence and its risk of lethality, the growth in services and programs was not based on research evaluating the effectiveness of hotlines, shelters, or legal policies to protect victims. A notable exception is the widespread adoption of pro-arrest policies after Reference Sherman and BerkSherman and Berk (1984) publicized the findings from their Minneapolis research indicating that arresting the batterer reduces the chances of continued partner violence. Data collected by the authors show that prior to the mid-1980s few jurisdictions had proactive arrest policies, yet beginning in 1984 the trend of aggressive arrest policy rose dramatically. The immediate response of policymakers to research findings demonstrates the desire for scientific guidance in this area. However, we must be cautious before designing policy based on a single set of findings. Replication studies of the Minneapolis project found that arrest may have no effect or can actually increase the chances of future violence in some situations (Reference Hirshel, Hutchinson, Dean, Kelley and PesackisHirshel et al. 1990; Reference ShermanSherman 1992).

The lack of quality research on which to base policy is not due to a lack of skilled or motivated researchers, but rather to the scarcity of data for assessing resource effectiveness across a broad range of services, multiple sites, and differing victim characteristics. The evaluations conducted by Sherman and other researchers focused on the impact of a single intervention—arrest—on already violent homes (see Reference Berk, Campbell, Klap and WesternBerk et al. 1992; Reference Dunford, Huizinga and ElliottDunford, Huizinga, & Elliott 1990; Reference Hirshel, Hutchinson, Dean, Kelley and PesackisHirshel et al. 1990; Reference Pate and HamiltonPate & Hamilton 1992; Reference Sherman and BerkSherman & Berk 1984; Reference Sherman, Schmidt, Rogan, Smith, Gartin, Collins and BacichSherman et al. 1992). Furthermore, each experiment was limited to one city, weakening the generalizability of the results (Reference ShermanSherman 1992). The divergent findings of the several experiments highlight the importance of including multiple cities in a single analysis of policy effectiveness.

Other research has utilized comparative designs that incorporate data for several types of domestic violence resources from a large number of jurisdictions. Reference Browne and WilliamsBrowne and Williams (1989) examined the effects of domestic violence services and legislation on intimate-partner homicide rates using state-level cross-sectional data. Their findings indicate some policy impact: greater service availability is significantly associated with a lower rate of married women killing their husbands. However, service availability was not found to be related to lower rates of men killing their wives (see Reference Browne, Williams, Dutton, Smith and ZahnBrowne, Williams, & Dutton 1999 for discussion). The finding of divergent effects of domestic violence services on intimate-partner homicide by gender was replicated in a longitudinal analysis of intimate-partner homicide victimization in 29 large U.S. cities (Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld 1999). The authors found that legal advocacy services are associated with reduced victimization for married men, but not for women (Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld 1999).

The above studies reach an ironic conclusion: resources designed to protect women from violent men appear to have a stronger role in keeping men from being killed by their partners. Men's homicidal behavior toward female intimates statistically remains the same regardless of the amount of resources available to battered women. Although there are clear social benefits to averting both the murder of men and the likely incarceration of the female perpetrator, the null female findings suggest that policy enhancements are needed to dramatically increase the safety of women in relationships with men.

The current study extends prior research by examining the effects of state statutes and local policies, programs, and services on intimate-partner homicide victimization in 48 large U.S. cities. Our analysis is based on six waves of intimate-partner homicide data between 1977 and 1996 for eight victim categories defined by sex, race, and marital relationship to the offender. We estimate the effects of 11 different measures of domestic violence resources based on state- and city-level data for the years 1976–1993. The analysis controls for nonintimate-adult homicide rates as a proxy for adult violence in general. Further, because of their direct relevance to exposure reduction, we additionally control for marriage and divorce rates, women's relative educational attainment, and welfare-benefit levels in each of the cities. For each type of domestic violence resource, we test the hypothesis that increases in resources are associated with declines in homicide, net of the controls. That expectation is based on the concept of exposure reduction.

Exposure to Violence in Intimate Relationships

Exposure reduction refers to shortening the time that participants in a violent relationship are in contact with one another. This perspective on intimate-partner homicide assumes that any mechanism that reduces the barriers to exit from a violent relationship will lower the probability that one partner kills the other. For example, the availability of welfare benefits, by hypothesis, reduces a woman's exposure to violence by providing financial support for her and her children to leave an abusive partner. It is important to point out that resources or policies may have exposure-reducing consequences for persons who do not utilize them as well as for those who do. The availability of public assistance or no-fault divorce could deter partner violence by informing men (and women) that women have options and do not have to remain in an abusive relationship. Knowledge of a mandatory arrest policy may influence the behavior of would-be offenders or victims. Indeed, such policies have been heavily promoted for just this purpose.

Exposure reduction can come in many forms. We focus primarily on a mechanism for exposure reduction that is legally mandated and available to women who want reprieve from violent relationships: protection orders. Protection orders are legally binding court orders that prohibit assailants from further abusing victims. Some orders direct the assailant to refrain from having any contact with the victim. These “no-contact” protection orders, our focus in this study, are an institutionalized form of exposure reduction.

Although the idea of exposure reduction is relatively straightforward, its effects on violence need not be. Substantial evidence shows that the highest homicide risk is during the period when a battered victim leaves the relationship, suggesting a potential “retaliation effect” from exposure reduction associated with domestic violence interventions (Reference Bernard and BernardBernard & Bernard 1983; Reference Campbell, Radford and RusselCampbell 1992; Reference Crawford and GartnerCrawford & Gartner 1992; Reference GoettingGoetting 1995). Such retaliation effects could occur if the intervention (e.g., restraining order, arrest, shelter protection) angers or threatens the abusive partner without effectively reducing contact with the victim. As with exposure reduction itself, retaliation can be motivated by knowledge of supportive or protective resources for women, particularly in men who believe such services deprive them of their rightful authority or control in intimate relationships. Moreover, some interventions may have exposure-reducing consequences for some categories of victims and retaliation effects for others. For example, if the criminal justice system better protects married white women than unmarried women of color, results might show resources associated with fewer white married homicides and more unmarried African-American homicides.

Given the paucity of research on the effects of domestic violence resources, we do not have an empirically verified “policy theory” from which specific hypotheses can be derived regarding the exposure-reduction or retaliation effects of a given resource type for a given type of victim. Nonetheless, it is important to situate research on domestic violence within broader criminological frameworks. Our thinking about intimate-partner homicide is guided at the most general level by control and strain theoretical orientations. Effective exposure reduction diminishes the opportunities for violence in intimate relationships. Opportunity is a key construct in control theories, which posit that persons commit crime and violence when they are free to do so (Reference Gottfredson and HirschiGottfredson & Hirschi 1990; Reference HirschiHirschi 1969; Reference KornhauserKornhauser 1978). Retaliation effects are triggered by interventions or other conditions that increase the motivations for violence without a corresponding decrease in opportunities. Strain theories focus on the motivations for crime and violence, predicting that such motivations are stimulated when aspirations or goals are frustrated or when persons are presented with negative or noxious stimuli (Reference MertonMerton 1968; Reference AgnewAgnew 1992). Explanatory frameworks based on feminist theories are broadly consistent with a strain interpretation of retaliation effects in so far as men react violently when they perceive their “right” to dominate and control their female partners is violated by the provision of protective resources (Reference Dobash and DobashDobash & Dobash 1992).

Although we contrast the predictions of control and strain theory as distinct outcomes, we recognize that they do not specify mutually exclusive or independent dynamics. As mentioned above, motivations for violence may be intensified by a sudden change in opportunity. With sufficiently high motivation (or strain), even the smallest exposure can provide enough opportunity for severe violence or death. It is not possible to directly test the interaction of these individual-level dynamics in this research. Rather, our intent is to identify patterns in policy responses that are consistent with the predictions of exposure reduction or retaliation.

Further, while often treated as social-psychological perspectives, both the control and strain theoretical orientations can be adapted to the macro-level of analysis (see Reference AgnewAgnew 1999; Reference Messner and RosenfeldMessner & Rosenfeld 2001). In the classic Mertonian formulation, strain emanates from the lack of articulation between cultural goals and the legitimate means for attaining them (Reference MertonMerton 1968). Reference AgnewAgnew (1999) recently showed how general strain theory applies to differences in community crime rates. Similarly, Travis Hirschi has acknowledged that his control theory can be formulated at the level of communities (Reference Lilly, Cullen and BallLilly, Cullen, & Ball 1989:105).

Domestic violence resources are characteristics of communities. For a specific community at a specific time there is no variation in the potential availability of resources across individuals.Footnote 6 This fact has two implications, one methodological and the other substantive. Because all individuals residing in the same place and time have the same value on a measure of domestic violence resources, the community-level analysis in this study is not vulnerable to the classic problem of nonequivalence in cross-level inference, or the so-called ecological fallacy (Reference LiebersonLieberson 1985:113–15). Substantively, where domestic violence resources are plentiful, the level of exposure reduction is higher, opportunities for partner violence are restricted, and rates of intimate-partner homicide should be lower. Alternatively, a high level of exposure reduction may generate strain and retaliatory violence in groups or environments where norms support male control in intimate relationships.

Recognizing the limitations of generalizing individual-level dynamics to macro-level associations, the present research does not test these alternative theories of the sources of violent conduct in intimate relationships. Furthermore, prior research offers little basis for deciding a priori whether specific domestic violence resources reduce opportunities or increase motivations for violence. Rather, the theories serve as guides for organizing and interpreting our findings, resulting in more refined hypotheses for future explanatory investigation.

Domestic Violence Resources

The intricacies of the justice system sometimes inhibit victims from seeking legal protection. To remedy this, domestic violence service providers in the late 1970s began to advocate on behalf of abused women. Dugan, Nagin, and Rosendfeld's (1999) finding that legal advocacy is associated with reductions in the rate women kill their husbands led us to speculate that this impact is related to the assistance such services provide women in obtaining protection orders—legally binding “exposure reduction.” As women seek legal remedies to domestic violence, they are less inclined to resort to lethal remedies (Reference Browne and WilliamsBrowne & Williams 1989; Reference PetersonPeterson 1999). Therefore, communities with extensive legal advocacy services should have lower rates of intimate-partner homicide.

Our analysis incorporates measures of the scope and intensity of legal advocacy services, as well as several dimensions of state and local policy related to protection orders. Before describing the specific measures, we discuss briefly the purpose and development of these key domestic violence prevention resources.Footnote 7

State Statutes

Reference Finn and ColsonFinn and Colson (1998) conclude that the utility of protection orders depends on their specificity, consistency of enforcement, and the ease with which they are obtained. The specific provision of state statutes with arguably the greatest protective value for victims is, as mentioned, whether they permit the courts to order no contact with the victim or, under some circumstances, other family members. A second key legal provision is expanded eligibility to cover victims who do not live with the abuser. Custody is a third provision that strengthens protection orders by authorizing the court to award temporary custody of children to the victim. A battered woman may be more likely to file for a protection order if she knows that she is likely to obtain temporary custody. Exclusive custody to the nonviolent parent lessens the need for contact, further reducing exposure.

Three additional legal provisions concern the consequences of violating a protection order and the nature of enforcement. If the state statutes allow for a warrantless arrest when a protection order is violated, the victim's exposure to risk is reduced because she does not have to wait until a warrant is requested and granted. Some states require police officers to arrest the violator. Mandatory arrest provisions, in principle, eliminate the police officer's discretion in making an arrest once probable cause is established. Once an arrest is made, violators may be charged with contempt (either civil or criminal), a misdemeanor, or a felony. In general, confinement is more likely to occur if the violation is classified as contempt or a felony rather than as a misdemeanor. Therefore, statutes that allow charge discretion probably do not reduce exposure as effectively as those that limit the nature of the charge for violating a protection order.

As this discussion implies, strong statutory provisions are a necessary but not sufficient condition for the effectiveness of protection orders. Local policies that reinforce statutory directives also are necessary to ensure compliance and effective enforcement.

Local Policy and Services

Local policy reinforces state law by affirming its importance to local police and prosecutors, by providing specific implementation procedures, or by augmenting statutory requirements where such discretion is permitted. The most important form of reinforcement is arrest policy. Pro-arrest policies encourage or require officers to arrest for violation of a protection order. Mandatory arrest policies further strengthen statutory directives by prohibiting officers from using threshold criteria such as serious injury of the victim as a condition for arresting the violator (Harvard Law Review 1993). Mandatory arrest policies for domestic violence, regardless of whether the victim possesses a protection order, signal police officers and the community that local law enforcement officials consider domestic violence a serious crime, which is the primary basis for whatever deterrent effectiveness they may have (for a brief history on changes in police response to domestic assault cases, see Reference Ferraro, Price and SokoloffFerraro 1995).Footnote 8

Statutory powers are likely to be most effective when accompanied by clear policies and procedures that provide guidance for police response to domestic violence, such as specialized domestic violence units and training in local law enforcement agencies. The effectiveness of the criminal justice response to domestic violence also depends on local prosecutorial policy, including the willingness to prosecute violators of protection orders, written policies to direct such cases, specialized domestic violence units, legal advocates on staff, and a “no drop” policy. Prosecutors tradition-ally had little incentive to take domestic violence cases due to evidentiary problems and victim ambivalence (Reference FaganFagan 1995). Therefore, the willingness to prosecute protection order violation cases is an elementary but important indicator of local support for state statutes. Written policies to delineate responsibilities and procedures expedite case processing. Specialized domestic violence units may enhance the expertise of those handling domestic violence cases by facilitating continuous contact with other professionals and community members who work with victims and batterers, including legal advocates (Reference HartHart 1992). Having legal advocates on staff provides victims with important information about the adjudication process and with support during testimony.Footnote 9 A no-drop policy prohibits the victim from withdrawing charges after prosecution has commenced.

It is unclear that prohibiting victims from dropping charges increases their safety. Some victims withdraw their complaint because proceeding with prosecution would put them and their children in further danger (Reference Ferraro, Price and SokoloffFerraro 1995). Their concerns appear to be well founded. Reference Ford, Buzawa and BuzawaFord (1992) reports that over one-quarter of the defendants in the Indianapolis Prosecution Experiment reoffended before their cases went to trial. In general, local policy intended to assist victims by “putting teeth” into statutory provisions may have the unintended consequence of promoting retaliatory violence.

A key objective of this study is to identify aspects of community-based legal advocacy for victims of domestic violence that are associated with reductions in intimate-partner homicide. Although many factors influence a program's effectiveness, personnel and financial resources are essential to the success of legal advocacy. Dedicated funding for staff and expenses indicates a program's commitment and capacity to provide effective advocacy. Having lawyers on staff increases the expertise available to clients and expedites the legal process. We include one final type of domestic violence resource in our analysis, the prevalence of hotlines for abuse victims. Hotlines are among the earliest domestic violence services and for many victims constitute the first and sometimes only contact with a city's network of protective services, including legal advocacy and police and prosecutorial services (Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld 1999:194). Where hotlines are prevalent, abuse victims are more likely to reach help and may access more targeted domestic violence resources.

To summarize, we expect that state laws with provisions for no contact between victims and abusers and for warrantless and mandatory arrest will be associated with lower rates of intimate-partner homicide. The exposure-reduction effects of state statutes should be strengthened, in turn, by aggressive and specialized local enforcement and strong legal advocacy services. However, we do not expect that each of these factors will have similar effects for all victim types, for at least five reasons. First, discrepancies in implementation of policy or services can limit exposure reduction. Second, not all victims of domestic violence have equal access to the types of protection mandated by law and policy. For instance, protection orders were originally restricted to women married to their abuser. Third, victims may perceive barriers preventing access to legal protection. This may be more common for women of color and low economic status (Reference PetersonPeterson 1999). Fourth, violent relationships between unmarried partners may be more sensitive to outside intervention because the partners typically have fewer legal and financial dependencies than spouses and therefore are freer to leave. Finally, some interventions may increase the risk of lethal violence for intimate partners if they increase strain without reducing contact, and the increased risk may vary by marital status, race, or gender.

Other Protective Factors

A number of other factors unrelated to domestic violence policy, by hypothesis, reduce intimate-partner homicide by reducing the exposure of persons to violent or abusive relationships; we therefore include them as important controls in our analysis. Perhaps the condition with the most direct effect on exposure reduction is marital domesticity. Marital homicides continue to comprise the large majority of intimate-partner killings (Reference Greenfield, Rand and CravenGreenfield et al. 1998; Reference Rosenfeld, Blumstein and WallmanRosenfeld 2000). Marriage rates among young adults have dropped sharply over the past 25 years in the United States, while rates of separation and divorce have increased (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1998). Barring full substitution of nonmarital for marital incidents, fewer marriages mean fewer persons at risk for intimate-partner homicide. Besides the direct reduction of exposure that occurs when marriages end or do not develop, declining marital domesticity could also signal a change in the composition of intact marriages. Adults who do marry may be more selective in choosing partners and less likely to marry abusers (see Reference EdinEdin 2000). Finally, violent relationships may be more likely to end in divorce (see Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld 1999; Reference RosenfeldRosenfeld 1997, Reference Rosenfeld, Blumstein and Wallman2000 for evidence supporting the relationship between domesticity and intimate-partner homicide).

As marriage rates have declined, the economic status of women has risen over the past 25 years. Women's college completion rates, labor force participation, and income all have increased in absolute terms and relative to men's (see Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld 1999). The labor force and income gender gaps for African Americans are narrower than for whites, and African-American women's rate of educational attainment has for some years exceeded African-American men's.

The improved status of women is important from an exposure-reduction perspective because economic resources and educational opportunity lessen the dependence of women on abusive partners. Even the perception of low potential earnings may be enough to prevent some women from leaving life-threatening relationships. At the same time, improvements in women's status may generate retaliation from men who fear loss of status or control in intimate relationships, contributing to increased levels of partner violence (see Reference Baron, Straus, Malamuth and DonnersteinBaron & Straus 1984, Reference Baron and Straus1987; Reference RussellRussell 1975). Reference Allen Craig, Straus, Straus and HotalingAllen and Straus (1980) report that husbands are more likely to assault their wives when their wives' resources exceed their own, a finding supportive of “ultimate resource theory” (see also Reference Hornung, McCullough and SugimotoHornung, McCullough, & Sugimoto 1981; Reference Tauchen, Witte and LongTauchen, Witte, & Long 1991). Moreover, retaliatory violence need not be restricted to the strain associated with such resource inequality within households. Increased gender conflict and retaliatory violence might be observed throughout communities in which women's high or increasing educational attainment contradicts traditional norms of male superiority. Given the greater relative equality between African-American men and women, we might expect such retaliation effects to be especially significant among African Americans (see Reference PattersonPatterson 1998 for a discussion of status differences and conflict between African-American men and women).

For poor women with children, support provided through public assistance may cushion the financial impact of leaving an abusive partner (Reference Allard, Albelda, Ellen Colten and CosenzaAllard et al. 1997). Additionally, previous research has documented higher levels of violence in the lives of women on welfare (Allard et al. 1997; Reference Browne and BassukBrowne & Bassuk 1997; Reference Lloyd and TalucLloyd & Taluc 1999; Reference Tolman and RosenTolman & Rosen 2001; Reference BrushBrush 2000). Therefore, we incorporate in our analysis benefit levels for Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC). In 1996, President Clinton signed legislation requiring states to replace AFDC with time-limited assistance (Reference Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, Harris and CurtisDuncan & Brooks-Gunn 1998). However, AFDC benefit levels began falling well before the program was eliminated, dropping in real terms by 37% over the years we are investigating (House Ways and Means Committee 1996). From an exposure-reduction perspective, communities with higher AFDC benefit levels, other things equal, should have lower rates of intimate-partner homicide.

Data and Methods

The analysis is based on a panel data set of 48 of the 50 largest U.S. cities for the years 1976–1996.Footnote 10 New York and Charlotte were dropped from the analysis due to missing data. The dependent variable is the number of intimate-partner homicides partitioned by victim sex, race (African American, white, total), and marital relationship to the offender. We estimate separate panel models for the 12 possible combinations of victim sex, race, and marital relationship.

Homicide Data

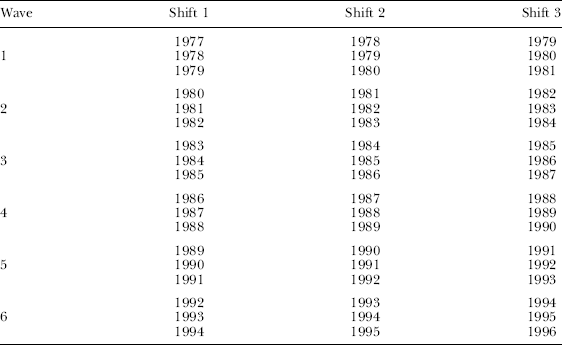

The homicide data were extracted from the Supplementary Homicide Reports (SHR) of the FBI's Uniform Crime Reporting program (UCR) (Federal Bureau of Investigation 1998). We aggregated to the city level for each year the number of homicides by the victim's sex, race, and marital relationship to the offender. Married persons include ex-spouses and common-law spouses; unmarried persons include the SHR categories of “boyfriend” and “girlfriend.” The small number of intimate-partner homicides involving a victim and offender of the same sex were excluded from the analysis.Footnote 11 The analysis is performed on three-year homicide counts for each city. Homicides were summed over the current and subsequent two years; when more than one of these years were missing, the case was deleted. When only one of the three years was missing, the summation was adjusted by a factor of 3/2 and then rounded to a whole number. Three-year sums are used because the rarity of intimate-partner homicides, especially when partitioned by victim sex, race, and relationship type, makes annual counts highly unstable. Summing over a three-year period is a smoothing procedure that reduces the amount of random variation and preserves the discrete nature of the data. To ensure independence across observations, every third year is used in the analysis. This creates six waves of data and three different “shifts” depending on the starting point of the summation: 1977, 1978, or 1979 (see Table 1).Footnote 12 Estimates from all three shifts were used to test the robustness of the results.

Table 1. Years of Each Shift During Each Wave

Domestic Violence Resources

The crux of the data-collection strategy was to seek out informants within the local agencies of the 50 largest cities and ask them to complete a survey inventorying policies or activities by type and year of implementation.Footnote 13 Time and budget constraints precluded collecting data from a larger number of cities. Even though repeated call-backs were required in some cases, response rates were impressively high, especially given the long time span for which we requested detailed information. We received completed surveys with no missing data on prosecutor policies for all 50 cities, police policies for all but New York and Charlotte, NC, and domestic violence services for all but New York, yielding a final sample of 48 cities. Although the accuracy of the information we received, particularly for the earlier years, depends on the quality and extensiveness of agency record keeping, we sought to minimize measurement error by identifying the person(s) best positioned in the agency to answer our questions, and by phrasing the questions in a standardized format, typically calling for a simple “yes/no” response. (The survey instruments for the local agencies and the coding protocol for the state statutes are available from the authors by request.) We recognize that by using this strategy, the validity of the data is a function of the selected informant in each city. For this reason, two rigorous sensitivity tests (described below) are conducted to identify findings that could be driven by measurement error in any one city or time period.

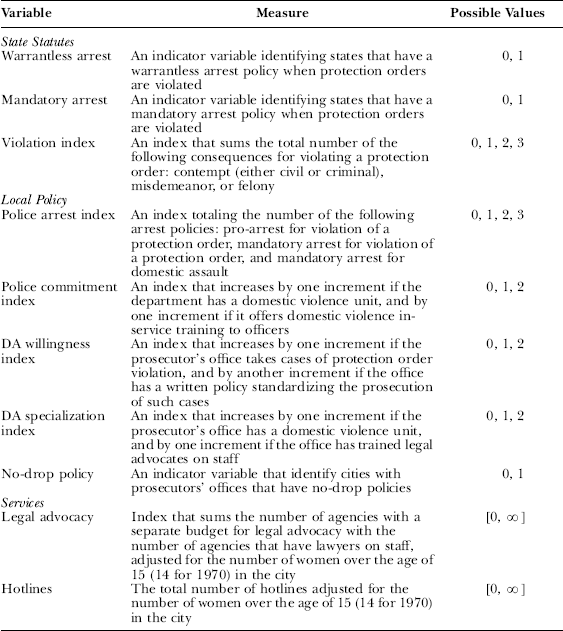

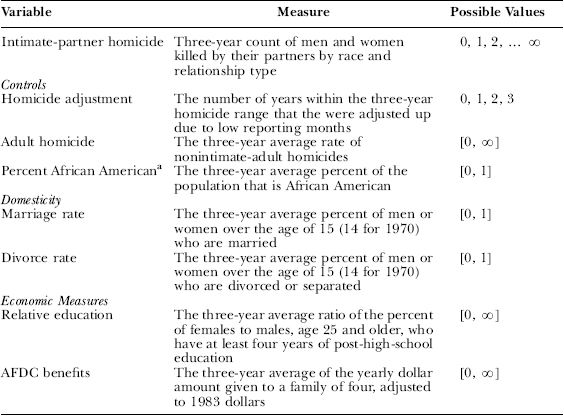

We incorporate all the domestic violence resources discussed above into 11 indicators of domestic violence resources, as shown in Table 2. Four are measures of state statutes, including provisions for warrantless arrest, mandatory arrest, an index of the legal consequences for violating a protection order (contempt, misdemeanor, or felony), and an “exposure-reduction” index that increases in value with provisions for no-contact orders and custody relief. Five of the indicators measure components of local policy, including police arrest policies, the presence of domestic violence units and training in police agencies, the willingness of prosecutor's offices to take domestic violence cases and the use of written policies for prosecuting them, the presence of domestic violence units and legal advocates in prosecutor's offices, and whether the prosecutor's office has a “no-drop” policy. Two final indicators measure the strength of legal advocacy programs and the prevalence of hotlines in the city.

Table 2. Domestic Violence Resource Variables

Controls for Domesticity and Economic Status

The impact of domesticity on homicide is estimated with marriage and divorce rates for each city and year. We use a single measure of relative economic status, the ratio of the proportion of women to the proportion of men age 25 or older with at least four years of post-secondary education. Prior research shows somewhat stronger effects of this measure than income or labor force participation ratios on intimate-partner homicide rates (Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld 1999). The marital and education measures are race-specific and were computed from city-level census data for the 1970, 1980, and 1990 census years (U.S. Bureau of the Census 1973, 1981, 1993). Values for the years between the decennial censuses were interpolated and then averaged over the appropriate three-year periods. We followed conventional practice in welfare analysis of measuring AFDC benefit levels based on the benefit received by a family of four persons. All figures are adjusted to 1983 dollars using the Consumer Price Index. Data on state AFDC benefits were obtained from annual versions of the “green book” compiled by the House Ways and Means Committee (1996).Footnote 14

Other Controls

Our analysis includes controls for four specific time-varying variables. The first accounts for factors associated with the overall change in adult homicide. We calculated the adult homicide rate (minus the intimate-partner homicides) for all victims ages 25 and over. The second control is for the percentage of a city's population that is African American. This variable is included in the racially aggregated models only. A third control was added to capture any bias that may be due to the adjustment procedure used to account for underreporting of SHR data. Because all adjustments were rounded to whole numbers, low counts such as 0 or 1 are unlikely to be rounded up to the next whole number after adjustment. This may result in a systematic undercounting of homicides. We therefore control for the number of years within the three-year homicide summation that were adjusted upward. Finally, to measure potential risk for homicide we include the natural logarithm of the number of persons in the relevant demographic subgroup for each three-year period (married white males, married African-American males, etc.). Because unmarried persons can be killed by intimate partners of any marital status, the equations for nonmarital intimates include the natural logarithm of the total number of males or females age 15 and over, by race. The Appendix summarizes each of the nonresource variables in our analysis.

Methods

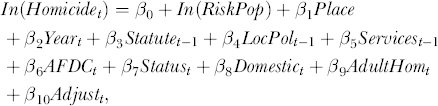

The dependent variable is a count of intimate-partner homicide victims within a discrete period (three years). Since rare events such as these are likely conform to a Poisson process, we use the Poisson likelihood function to estimate our models. Equation 1 shows the Poisson model with each observation weighted by the three-year average of the city's population:

where λit is the expected number of homicides and n is the number of persons at risk of homicide.Footnote 15 We estimate the statistical model shown in Equation 2 for each category of intimate-partner homicide as defined by the victim's sex, race, and marital relationship. The subscript t refers to the wave. Recall that each wave includes the current and two subsequent years. The subscript t−1 refers to the single year preceding the current wave.

where Homicide is the count of intimate-partner homicide victims, Statute refers to the state statute provisions, LocPol refers to the local policies, Services refers to legal advocacy and hotlines, AFDC refers to the state benefit levels, Status is the measure of women's relative education, Domestic refers to the marriage and divorce rates, AdultHom is the homicide rate for persons 25 and over, and Adjust is the adjustment for possible downward bias in the homicide counts due to rounding (see Appendix). We also include in the model dummy variables for each place and wave in the panel as controls for fixed effects attributable to time and place.

Additional methodology was designed to address five problems common to longitudinal policy analysis and policy assessments: (1) by using both time and place fixed effects, little variation is left in the model to efficiently identify the effects of the explanatory variables on homicide; (2) results might be dependent on the inclusion of one or a few specific cities; (3) the association of one or more factors might be stronger during a truncated portion of the overall range of time; (4) the homicide counts may be endogenous to (i.e., precede in time) the explanatory variables; and (5) consequences of a type I error when assessing policy effects are more crucial than those for a type II error.

To address the first problem we consider three levels of place fixed effects (none, state, and city). Because results from analyses using city effects are the least likely to suffer from omission bias, their coefficient estimates and standard errors were used to create lower and upper confidence bounds to test for possible omission bias in the state-level and no-place fixed-effects models. All coefficient estimates that fall beyond the two-standard deviation bounds are suspected of omission bias and therefore considered with caution. When the model using no-place fixed effects met the above criteria, its estimate was chosen over that from the state fixed-effect model (see Reference DuganDugan 1999 for an extended discussion).

We test for city-dependent results by imposing a cross-validation sensitivity analysis that reruns all three shifts of each model after removing each city one at a time. After sorting the resulting t-statistics, we can determine if the significance of a variable is dependent on the inclusion of any one city. We conclude that a result is city-dependent if, by removing that city, all three shifts fall on the opposite side of the significance threshold than with the city included. If by dropping a city, the significance or sign of a result reversed in all three shifts, then the city-dependency test was rerun without that city to assure robustness.

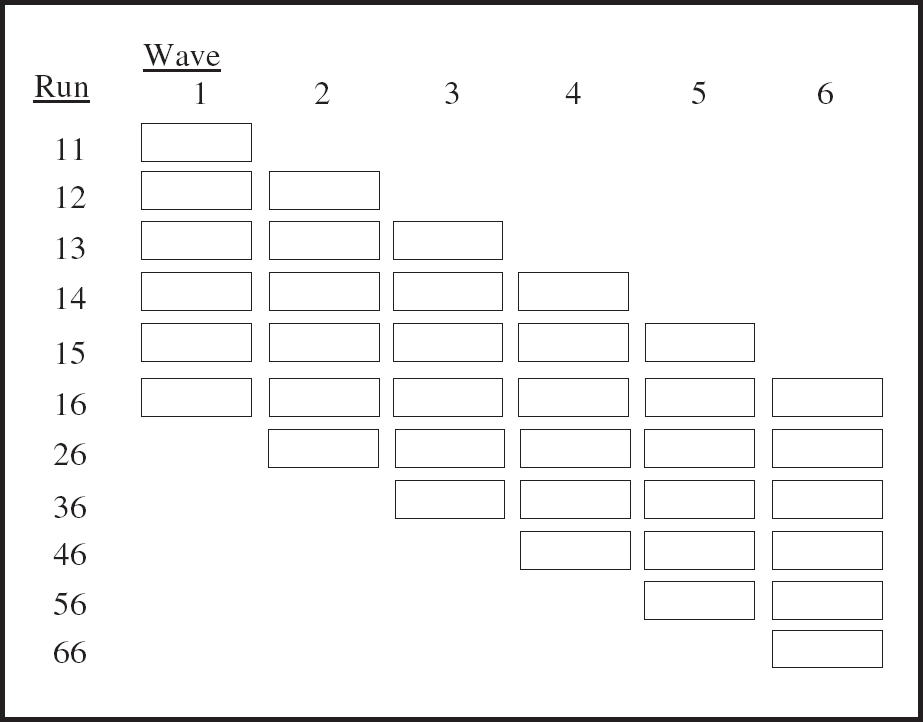

To address the third problem, we test for time dependency as illustrated in Figure 2. Each column in the figure represents a wave of data, and each row represents a range of waves included in each “run” of the sensitivity test. The run is identified by its first and last wave. For instance, the first run (11) only includes Wave 1 (48 cities and one time period).Footnote 16 The second run (12) includes Waves 1 and 2, the third (13) includes Waves 1, 2, and 3, and the sixth run (16) includes all six waves of data. The early runs allow us to assess the estimated impact of each variable in the beginning waves of our data. Similarly, the later runs include only the latter portion of the data, truncated at different waves, permitting us to evaluate the estimated impact of each variable later in the time period.

Figure 2. Test for time dependency.

The fourth important consideration with this type of data is endogeneity. Changes in one or more of the explanatory variables—especially related to policy—may have been provoked by changes in the dependent variable—perhaps a highly publicized homicide. For example, if police departments on average adopt more aggressive arrest policies after one or more widely publicized cases of men killing their ex-wives, it might appear that aggressive arrest policies lead to more homicides. Conversely, policy provoked by an unusual increase in homicides could receive undue credit for its natural decline. Because laws, policies, and services are often adopted in response to a need, such measures are especially sensitive to this type of problem. We address the problem by lagging the resource variables by one year. The resource variables, therefore, describe the entry condition at the beginning of each wave. The economic and domesticity variables are unlikely to be endogenous and are averaged over the same three-year period used for the homicide sums.

Finally, given the potentially serious consequences of falsely concluding that a policy is significantly associated with a change in intimate-partner homicide, we impose a strict significance criterion for robustness. All three shifts (see Table 1) must be significant at or beyond a two-tail 0.01 level for a finding to be considered robust.

Presentation of the results is complicated because of the multiple dimensions of the sensitivity analysis. The estimates may be generated from models using state fixed effects or those that exclude any place fixed effects. They could represent the overall effect from the entire sample of 48 cities or a smaller sample that omits one or two influential cities. And, the estimates may be generated from all six waves of data or from a subset of the whole. One final complication is that because we summed the homicide data over three consecutive years, three different estimates are generated from the resulting shifts. In total, approximately 360 estimates are generated for each variable in each model (2 types of fixed effects×(49 sample combinations +11 wave ranges)×3 shifts).

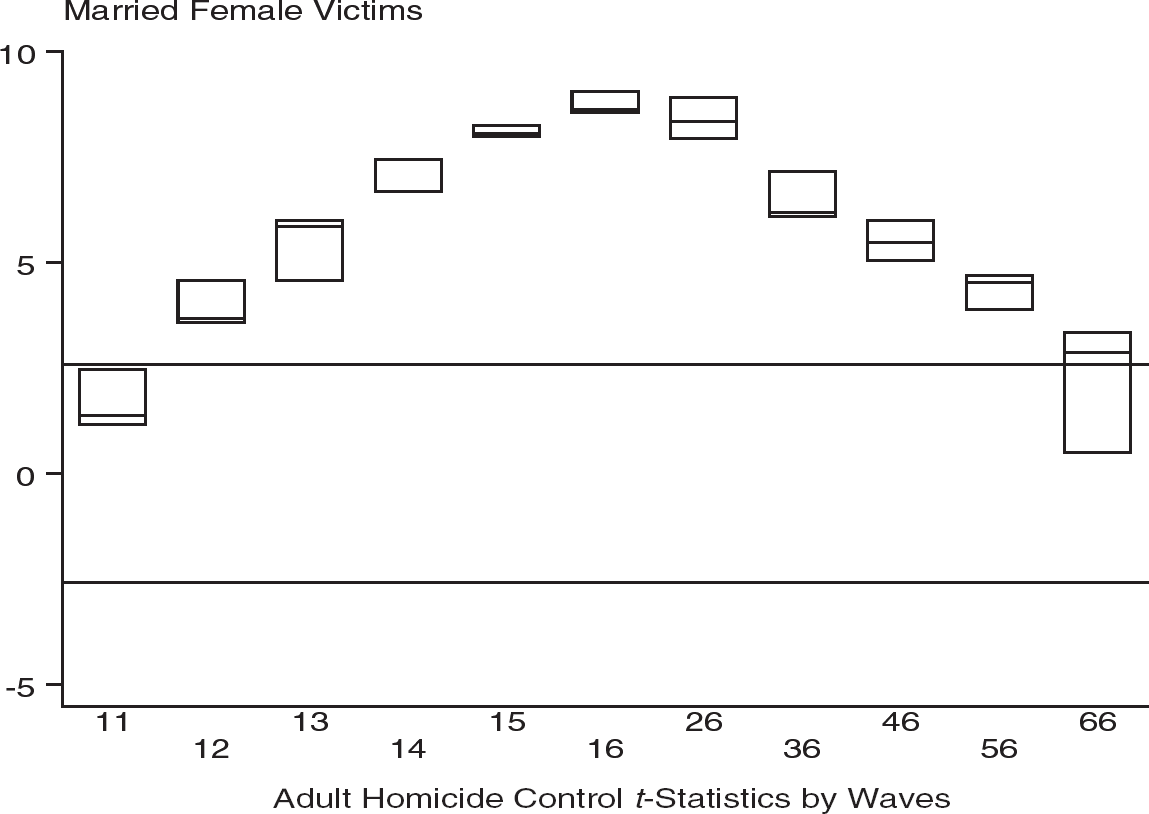

After conducting the city-dependency tests, we used a graphical method to examine the estimates for robustness. To illustrate, box plots of t-statistics relating nonintimate-adult homicide to married female victimization are presented in Figure 3. Each horizontal line within the boxes represents a t-statistic from one of the three shifts. The horizontal lines in the graph are placed at the two-tailed 0.01 significance level (±2.56). Each box represents the wave range that was used to generate the t-statistics. The center box, labeled 16, uses all six waves. Similarly, the box to its left, labeled 15, uses only the first five waves. When boxes fall above both lines, then the factor is positively related to intimate-partner homicide, and when they fall below the association is negative. If any portion of the box falls between the two horizontal lines, the finding is considered null for that wave range. As expected, the adult homicide rate is positively related to married female victimization.

Figure 3. Adult homicide on married female victims.

Similar graphs were generated for each of the 15 hypothesized exposure-reducing factors in all 12 models to identify robust associations. For the reasons explained above, the no-place fixed-effect model is chosen over the state fixed-effect model if it falls within the two standard deviation bounds defined by the city fixed-effect model. If by removing one city the t-statistics of all three shifts in the full wave model fall completely in or out of the significance range, then that model is chosen over the 48-city model.

Results

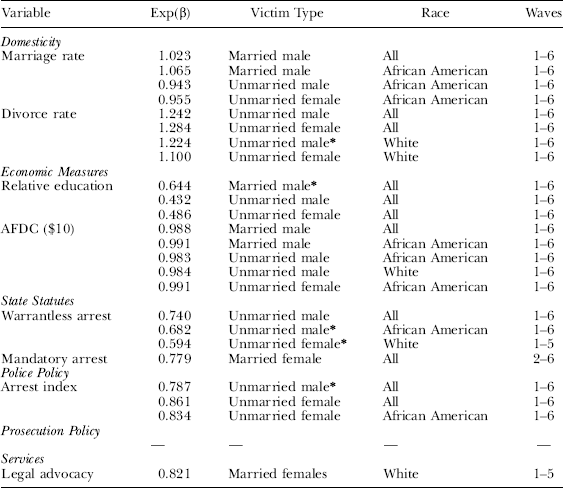

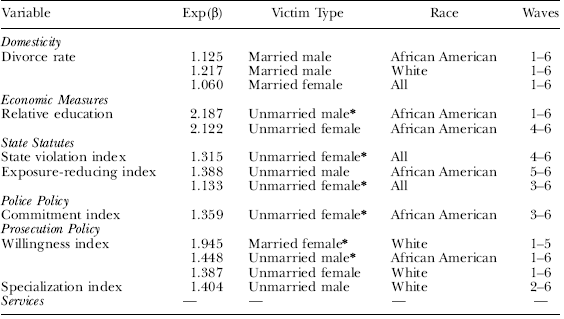

The findings that are consistent with exposure reduction are summarized in Table 3a. Those consistent with the predictions of the retaliation hypothesis are found in Table 3b. Exponents of the coefficient estimates are presented to show the magnitude of each result. The results can be dependent on omitting a city or a specific range of waves. Listed under “Waves” is the broadest range in which all three shifts are significant.

Table 3a. Robust Findings that Support the Exposure-Reduction Hypothesis

* At least one city is omitted.

Table 3b. Robust Findings that Support the Retaliation Hypothesis

* At least one city is omitted.

Of the 180 possible associations (15 factors×12 victim types), 37 pass all tests of robustness (21%). Because we report the exponents of the estimates, values greater than one show a positive association with homicide and those below one indicate a negative association. Of these findings, 24, or 65%, conform to the predictions of exposure reduction, indicating that, more often than not, communities with more abundant alternatives to living with, or depending on, an abusive partner have lower levels of intimate-partner killings. The remaining 35% are consistent with the retaliation hypothesis: The increased killings associated with availability of resources intended to reduce exposure to violence may be due to retaliation from batterers once their partners try to leave or from other men angered or threatened by domestic violence prevention activity in the community.

Two policy-related findings that show strong support for exposure reduction are those for AFDC benefit levels and police arrest policy. Interpretation of the AFDC results is somewhat ambiguous because benefit levels vary within cities and we do not have the data needed to model that within-unit variance. It is possible, therefore, that the relationships between benefit levels and intimate-partner homicide levels that we observe between cities differ from the corresponding relationships across households within cities. With that caveat in mind, the between-city relationships imply that the homicide victimization of unmarried men, particularly African-American men (as indicated by the lowest Exp(β)) is most strongly affected by changing AFDC benefit levels. As AFDC benefits decline, more men are killed by their girlfriends. One possible reason is that reductions in AFDC limit financial opportunities for unmarried women with children to live independently of their abusers. Without perceived alternatives, these women may be more likely to kill their abusers. Not surprisingly, this type of increased exposure also appears to endanger the lives of African-American unmarried women. However, white women are unaffected, suggesting that African Americans are more sensitive to variations in AFDC (see also the results for married men). That interpretation is consistent with the higher rates of AFDC participation of African Americans compared with whites (House Ways and Means Committee 1996).

The findings for police arrest are also consistent with exposure reduction: adoption of more aggressive arrest policies is related to fewer deaths of unmarried intimates. In contrast, the association between arrest policy and spousal homicide is null. There are at least three possible explanations for this difference. First, aggressive arrest policy could have a stronger deterrent effect on unmarried than married batterers, which if true would contradict Sherman's (1992) “stake-in-conformity” explanation. Alternatively, police may more often choose to enforce arrest policy on unmarried violent intimates. Inspection of the box plots displaying the effect of police arrest policy on unmarried female victimization (not shown) suggests that the relationship for the total population is driven by that for African-American victims. This finding raises a third possibility that the association between aggressive arrest policies and marital status is spurious, due only to the lower marriage rates for African Americans than whites. This interpretation is unlikely, however, because arrest policy is unrelated to male or female victimization when African-American married and unmarried intimates are analyzed together.

Four additional variables consistently support the predictions of exposure reduction across all victim types for which there is a robust association: marriage rates, legal advocacy, warrantless arrest laws, and mandatory arrest laws. In communities with lower marriage rates, fewer men are killed by their wives. However, after separating victims by race, the influence on spousal homicide of declining marriage rates is observed only among African-American men. Moreover, as marriage rates among African-American men and women decrease, the rate of homicide among African-American unmarried intimates increases, suggesting some displacement of intimate violence from marital to nonmarital partnerships.

The policy-related findings show that increases in the strength of legal advocacy are associated with fewer killings of white women by their husbands in the first five waves. Similarly, the adoption of a mandatory arrest law is associated with fewer deaths of married women of all races during the last five waves. Finally, the adoption of warrantless arrest laws is related to decreases in the homicides of unmarried male intimates, especially those who are African American, and unmarried white females. None of the measures of prosecution policy support the predictions of exposure reduction.

The only policy-related finding that consistently and strongly opposes the exposure-reduction hypothesis across multiple victim categories is prosecutor willingness. As prosecutors adopt policies stating their willingness to prosecute violators of protection orders, we observe increases in homicide for white females, both married and unmarried, and African-American unmarried males. This result suggests that being willing to prosecute without providing adequate protection may be harmful.

Four additional findings imply limited retaliation to policy intervention, that is, the retaliation effects are restricted to particular victim categories or time periods. All four are robust only during the latter years, for only one victim type, and only for unmarried victims. Communities with increased police commitment in the form of training and domestic violence units exhibit elevated numbers of African-American women killed by their boyfriends (Waves 3–6). As prosecutors' offices become more specialized, more white men, on average, are killed by their girlfriends. The indices of state violation and exposure reduction are associated with elevated killings of unmarried females of all races. Finally, areas with more exposure-reducing laws are characterized by more homicides of African-American males by their girlfriends.

The two remaining robust findings fail to consistently support or oppose the exposure-reduction hypothesis across victim types. As expected, increases in divorce are related to increases in the killing of unmarried partners, presumably because increases in divorce result in larger pools of unmarried individuals exposed to potentially violent partners (see Reference Dugan, Nagin and RosenfeldDugan, Nagin, & Rosenfeld 1999 for a similar finding). However, increases in divorce are also related to more killings of spouses. This finding is not entirely surprising in light of prior research showing that the most dangerous time in a relationship is as it is ending (Reference Bernard and BernardBernard & Bernard 1983; Reference Campbell, Radford and RusselCampbell 1992; Reference Crawford and GartnerCrawford & Gartner 1992; Reference GoettingGoetting 1995).

Finally, women's increasing educational status is associated with lower levels of intimate-partner homicide when all races are combined, but with higher levels of homicide for African Americans in nonmarital relationships. The race difference may be due in part to the differing pattern of gender inequality for whites and African Americans. For whites, the trend since the 1970s in relative education reflects the growing equality of women to men. However, African-American men and women were nearly at educational parity 20 years ago. By the mid-1990s, the proportion of African-American women with at least four years of post-high-school education exceeded that for African-American men by more than 20%. Therefore, increases in relative education among African Americans represent a growing disparity between the genders. The positive effect detected in this study suggests that the large difference in educational attainment could add more stress to already contentious relationships, creating retaliation (see Reference Baron, Straus, Malamuth and DonnersteinBaron & Straus 1984, Reference Baron and Straus1987; Reference RussellRussell 1975; Reference Allen Craig, Straus, Straus and HotalingAllen & Straus 1980; Reference Hornung, McCullough and SugimotoHornung, McCullough, & Sugimoto 1981; Reference Tauchen, Witte and LongTauchen, Witte, & Long 1991).

Discussion

The goal of this article was to identify factors that have contributed to variation in intimate-partner homicide across place and time in the United States. Our research was premised on a simple hypothesis of exposure reduction, predicting that any factor that shortens the time that violent intimates are exposed to one another will reduce the probability that the relationship ends in homicide, thus ultimately contributing to the overall decline observed in intimate-partner homicide. The investigation produced mixed support for the hypothesis. Most findings support it, but others imply that exposure-reducing resources may have lethal consequences. More aggressive arrest policy is associated with fewer killings of unmarried intimates. Increases in the willingness of prosecutors' offices to take cases of protection order violation are associated with increases in the homicide of white females, both married and unmarried, and African-American unmarried males. An untoward consequence of cutting AFDC payment levels may be increased homicide victimization of African-American married men, African-American unmarried partners, and white unmarried females, although firm conclusions must await an assessment of within-city variation in benefit levels.

Although we have not directly tested the control versus strain interpretations of the effect of policy on intimate-partner homicide, our results indicate that both theoretical approaches are useful in guiding future research in this area. The challenge is to specify the conditions under which exposure-reducing “opportunity” and retaliation-inducing “motivational” effects should occur. Exposure reduction is an intuitively appealing prevention strategy, but the results show that reality is more complicated than the theory suggests. By only measuring the policy input, we miss information on who accesses the system and how well the policy is implemented. Results from a recent national survey on violence against women show that more than 73% of the women who were physically assaulted by an intimate did not report the incident to the police. The leading reason was their belief that the police could not help (Reference Tjaden and ThoennesTjaden & Thoennes 2000). Furthermore, evidence of increased lethality, and even the null findings, could reflect failures within the criminal justice and social service systems to adequately protect victims once they access services. Or, the most violent relationships may require that exposure be reduced to zero contact. However, intimate partnerships are inherently difficult to end without some contact, especially if the couple share children or property (Reference Campbell, Rose, Kub and NeddCampbell et al. 1998).

These findings do not mean that designing prevention strategies based on exposure reduction is a bad idea. They do, however, suggest that a little exposure reduction (or unmet promises of exposure reduction) in severely violent relationships can be worse than the status quo. Absolute reduction of exposure in such relationships is an important policy objective. But achieving this type of protection from abuse is not easy. Our study investigated the community-level characteristics associated with exposure reduction. More research at the individual level is needed to better understand the dynamics of successful exposure reduction compared to unsuccessful cases so that policymakers and practitioners can reduce prevention failures. Much research has already been conducted on failed efforts to leave abusers. Homicide case reports and interviews often provide rich details of the events leading to the homicide. Yet, this is only half the story. For comparison we need to understand how severely violent relationships avoid lethal consequences. Too commonly we assume that we already know the counterfactual to intimate-partner homicide without systematic investigation. Progress is being made with longitudinal research on battered women by Reference Campbell, Rose, Kub and NeddCampbell and colleagues (1998, Reference Campbell and Soeken1999) that examines how women who differ in individual and relationship attributes respond to partner abuse. Ongoing research is assessing women's risk of homicide in intimate relationships by comparing homicide victims to survivors of near-homicide, battered women, and other women who are not battered in 11 major U.S. cities.Footnote 17 Only with additional research documenting successful and unsuccessful cases of relief from partner violence for a heterogeneous group of women we will be able to design policy customized to meet their safety needs.

This research was funded by grants from the National Institute of Justice and the National Consortium on Violence Research. We would like to thank Martha Friday, Lorraine Bittner, Lynn Kacsuta, and Kerry Taylor from the Pittsburgh Women's Center and Shelter; Detective Mary Causey, Julie Kuntz Field, Barbara Hart, Dawn Henry, and the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Domestic Violence for their efforts, guidance, and support, which was crucial to the success of this research. Finally, we offer our sincere gratitude toward Angela Browne and anonymous reviewers. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 1999 meeting of the American Society of Criminology, the 1999 meeting for the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management, the 2000 meeting for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the 2000 National Institute of Justice's Research Conference on Violence Against Women and Family Violence.

Appendix: Model Variables

a This variable is only in the racially aggregate models.