Chapter 4 “Quod piers plowman”: non-reformist prophecy, c.1520–1555

If most Piers Plowman excerpts strike a communal chord on account of their aphoristic, even scholastic, character, others' populism comes from a different place altogether. Especially in the sixteenth century, an anti-intellectual, oral, prophetic, and, crucially, non-reformist mode, so I will argue, was the predominant approach to Langland's poem, perhaps even in ignorance that what we would today call “excerpts” originated there at all. Six independent productions of c.1520–55 juxtapose B passus 6's “hunger prophecy” about Davy the Dyker with either of two passages, in B 10 and 19, that tell of a king who will correct “the abbot of Abingdon” and subjugate the religious. These standalone prophecies, like the detachable Latin of the manuscripts, have an uncomfortable relationship with the received Langland archive of this era, as constituted and interpreted so influentially by Anne Hudson: “Most of the references, real or apparent, in the two centuries after the composition of Langland's poem associate it with reforming views – most often with views that at the time of composition would have appeared radical or heterodox.”1

The foundation for this approach is solid: Robert Crowley's three 1550 editions of The Vision of Pierce Plowman, which characterize the era of the poet, whom he calls “Robert” Langland, as one when “it pleased God to open the eyes of many to se hys truth, geving them boldenes of herte, to open their mouthes and crye oute agaynste the workes of darckenes, as dyd John Wicklyfe” (sig. *iir).2 Crowley thus transforms the poem “into a prophecy of the advent of the Protestant millennium of the sixteenth century,” much as the rest of his era did, in the received account.3 Yet this account is backwards, as a more capacious, and more representative, archive of the sixteenth-century Piers Plowman shows. The Langland archive, so this chapter argues, has mistaken as the mainstream a mode that in fact constituted a rearguard attack on the predominant approach, which was decidedly non-reformist and oral.

Piers Plowman in Winchester: two monks' heads and political prophecy

The context of the item that brings our body of evidence into focus undoes any sense that the sixteenth-century Langland archive is inherently Protestant. The volume in question, BL Additional MS 60577, goes by a title that itself brings Catholicism back into the picture: “The Winchester Anthology.” “In the first half of the 16th century,” as John E. Paul observes, “few counties were more fundamentally Catholic in culture than Hampshire,” especially Winchester.4 These sympathies are amply manifested throughout the Winchester Anthology, which was produced over a century or so in the Benedictine priory of St. Swithun's or its successor after the dissolution of the monasteries, Winchester Cathedral. Most of the Anthology's contents, entered in the fifteenth century, are conventional enough – an Englishing of Book I of Petrarch's Secretum, lyrics, sermons, The ABC of Aristotle5 – but its later owners and their additions imbue the volume with a full-blooded Catholicism. Thomas Dackomb, who owned this volume from c.1549, had a book collection showing that “he remained loyal to the old religion,” remarks Andrew G. Watson;6 the next owner to have inscribed his name, William Way, a lay singing-man in the cathedral, added both a letter by the English Jesuit Ellis Heywood (fol. 108r) and the sermon given by Bishop John White of Winchester at the funeral of Queen Mary (fols. 191r–204r).

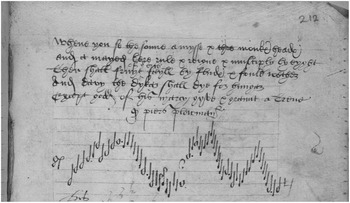

Among the volume's later items is an excerpt from Piers Plowman that has never figured in accounts of the poem's witnesses or histories of its reception.7 This is the only contribution by this hand, which is otherwise unattested in the collection (see Figure 6).8

Figure 6 “Two monks’ heads” prophecy in The Winchester Anthology.

The text is Piers Plowman B 6.327–8, 325 (after 329's Then), 330–1, which I will call the “monks' heads” or “hunger prophecy,” but it is the concluding tag, “Quod piers plowman,” that gets to the heart of this item's character. In the received poem the lines belong to the narrator; but here they constitute a free-floating text, which Derek Pearsall, in the sum total of commentary to date, describes as “a copy made from memory.”9 Memorize is what one does with prophecies, after all,10 and from its earliest appearance this passage attracted the sort of attention that would easily lead to its extraction from its written context into a standalone existence. Eight manuscripts of Piers Plowman feature some sort of marginal notation, for instance.11 “Langland seems to show little interest in the political prophecy of his day,” which was full of such celestial portents and numerological riddles; but when he did, his readers were quick to respond.12

The early fifteenth-century poet of Mum and the Sothsegger was one of them. The narrator of this member of “the Piers Plowman tradition” holds “halfe a-masid” those who “museth on the mervailles that Merlyn dide devyse.”13 No one knows what tomorrow's weather will be, or can construe what will happen next week:

The moon and heads that have “been hewe of ”: this is as close to Langland's “sun [Kane and Donaldson: mone] amiss” and “two monks' heads” as possible without a direct quotation. Closer to the Winchester copyist's milieu, the bodies belonging to these hewn-off heads would materialize, still under that vagrant moon. In 1537, one William Todd, prior of Malton in Rydale, told Cromwell's henchmen that “fourteen or sixteen years ago, he saw in Geoffrey Lancaster's hands a parchment roll ‘whereon was a moon painted growing, with a number of years growing as the moon did,’ where the moon was full a cardinal was painted, and beneath him the moon waned, and there were two monks, headless, one under the other.”14

Todd's interviewers were hard-wired to be terrified of the popularity of such Galfridian prophecies about moons and body parts, for “prophecies of one kind or another were employed in virtually every rebellion or popular rising which disturbed the Tudor state,” prophecies that during this period “circulated extensively throughout the country, particularly in the north of England, where the most active resistance to the government was to be found.”15 Keith Thomas reports upon a classic case of such resistance via prophecy, concerning one John Dobson, vicar of Muston, Yorkshire, that also shows, almost in the comic mode, that “prophecies could thus circulate extensively by word of mouth.”16

When examined, the priest confessed to having borrowed from the Prior of White Friars, Scarborough, a paper roll made by Merlin, Bede and Thomas of Erceldoune, containing predictions relating to the black fleet of Norway, the eagle, the Cock of the North, the moon, A.B.C., and the various other dramatis personae. The Prior of White Friars was then interrogated and explained that he had copied some prophecies from a priest at Beverley and from William Langdale, a Scarborough gentleman. William Langdale was duly apprehended and confessed to lending the Prior a rhymed prophecy about “A.B.C.” and “K.L.M.” which he had got from another priest, Thomas Bradley. Bradley pleaded in turn that his prophecies of Merlin and Bede came from William Langley, a parish clerk of Croft.17

It might seem surprising to find Piers Plowman caught up in the kind of turmoil that got people like John Dobson executed, but it often seems to present itself as a repository of the sorts of oral wisdom being passed from Langley to Langdale and on, eventually, to poor Vicar Dobson. A number of critics have suggested that many of Piers Plowman's features “imply an audience hearing the text rather than a readership seeing it,”18 and it seems to me that the best such indications are to be found in the records of oral performances. Perhaps William Todd's account seems too far removed from the poem to suggest direct influence, but the sermons of Thomas Brinton, bishop of Rochester from 1373 to 1389, are not.19 While the Winchester passage itself does not seem to have had a life at the pulpit, its close companion does, in a way that points to a new narrative of the post-Reformation Piers Plowman.

John Brynstan, heretic and apostate

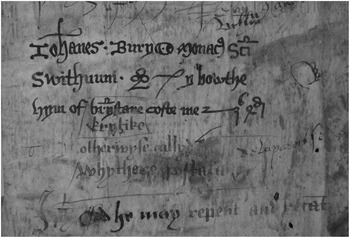

This assertion relies upon my proposed identification of the individual who inscribed the “monks' heads” prophecy into the Winchester Anthology. Edward Wilson dates the extract's hand to the early sixteenth century, but it is difficult to know for sure.20 It was already there by the time William Way, who refers to “the late bosshop of winton,” who died in June 1559 (fol. 191r), inscribed the musical notation that surrounds it; and the hand does not match that of any other contributors. One identifiable owner did not record his name, but jottings of his successor, on the end pastedown, identify him in spectacular fashion: “Johanes Bury[ton] Monacus sancti Swithuuni D y bowthe hym of brynstane coste me 3s 4d” (“John Buriton, monk of St. Swithun's, bought it from Brynstan. It cost me three shillings and four pence”; see Figure 7). In lighter ink Buriton later adds “Erytike” under “brynstane” and boxes the two terms, continuing in the same light ink, again boxed, “otherwyse callyd whythere postata.” The addendum concludes: “I pray God he may repent and recant.” Buriton was a sacrist of St. Swithun's, who also added bits on fols. 1r and 225v;21 the “heretic” and “apostate” who so arouses his ire must be the “Johannes Brynston,” monk of St. Swithun's, who was ordained deacon on December 22, 1520, and priest on March 21, 1522.22

Figure 7 Ownership inscription in The Winchester Anthology.

Wilson draws attention as well to another record relevant to Buriton's remarks, which takes us beyond the realm of Winchester, and either constitutes one of the most bizarre self-contradictions in the history of preaching or indicates a devotion to the prophecies of Piers Plowman. Brynstan's final appearance in the records of St. Swithun's is December 2, 1524. Eleven years later, on February 13, 1536, according to more of those reports collected by Cromwell's henchmen, an Austin friar named John Brynstan preached a sermon in Glastonbury Abbey church in which, according to one witness, he “said that ‘he would be one of them that should convert the new fanggylles and new men, other else he would die in the quarrel’,” while others added “also that he said that ‘all those that doth occupy the new books be lecherous and ready to devour men's wives and servants, and that he would be one of them that would bring down the new books, otherwise he would die in the cause.’”23 Attacks upon the “newfangledness” of “new men” were standard fare in anti-Protestant rhetoric,24 and Brynstan's performance would win the Glastonbury abbot a modern reputation in some circles as champion of the true faith in the face of King Henry's tyranny.25 Yet these apologies for Catholicism jar violently with the accounts of what he said next:

They all say that the friar expounded the King's title as Supreme Head of the Church to the King's great honor, and the utter fordoing of the bishop of Rome's authority, – quoting Scripture in support of it.

The friar answers that he said, “You with your new books, other ye be adulterers, filthy lechers, devourers of men's wives, daughters, or servants, other full of envy, malice, and strife, and ready to oppress and wrong your neighbours, and that I trusted to convert a great many of such erroneous persons, other to die in the quarrel.”26

“If Brynstan had upheld the king's title as Supreme Head of the Church,” Wilson points out, “then such support for Henry VIII would doubtless have caused Buriton (who would have approved of the attack on ‘new books’) to use the words ‘Erytike’ and ‘postata’.”27 What matters for us instead, though, is the blatant contradiction here between this praise of the king and the invectives against the Protestants. It might seem inviting to cite as a parallel the career of another sixteenth-century scribe of Piers Plowman, Sir Adrian Fortescue, who both held true to his Catholic faith and “conformed outwardly, at least, to the royal supremacy,” for instance by copying out in his missal a bidding prayer retaining Henry VIII's title “supreme hede immediately under God.”28 But if Fortescue ever accused reformers of devouring men's daughters, no record of it survives; and his missal's reference to Henry's supremacy was later cancelled, its owner being executed in July 1539.

Brynstan's performance begins to make sense, though, if his expounding of the king's title was not an endorsement of Henry's policies, but a prophetic warning against ecclesiastical self-complacency that sounded like this:

which goes on to predict that the abbot of Abingdon will be disendowed; or, from that king's own perspective, like this:

If he knew them – and as the next section will suggest, that seems likely, even if he did not know they were from a poem called Piers Plowman – Brynstan would have felt that these lines were speaking directly to him, a man so discontent with ecclesiastical abuses that he abandoned the priory.

Davy the Dyker and the abbot of Abingdon

Nearly all sixteenth-century readers who left records of their responses joined Brynstan (if my attribution is right) in homing in on the “monks' heads” lines. Readers of this era supplied the passage in one A and one C manuscript;31 most others juxtaposed them with the “king shall come” prophecies as I have suggested Brynstan did. Two of the three sixteenth-century full-scale B manuscripts are outliers: Tokyo, Takamiya MS 23 (olim Sion College MS Arc. L.40 2/E), one of only two witnesses to B that “have virtually no original marginal notes,”32 and Cambridge, Gonville and Caius MS 201/107, which faithfully reproduces Rogers's 1561 text and apparatus. The third B manuscript of this era is CUL MS Gg.4.31, the copy I quoted in the previous section, which calls the poem “The Prophecies of Piers Plowman,” emphasizing these as two of the poem's five “prophecies” via marginal glosses, a table of contents, and unique symbols enabling cross-referencing between the contents page and the text.33

The phenomenon is epitomized in Thomas Churchyard's Davy Dycars Dreame, most likely published three or so years before Robert Crowley's 1550 editions.34 “And davy the dykar shall dye for hungar,” warns “piers plowman” in the Winchester version; in Churchyard's pamphlet this figure speaks for himself, his “dream” expressing the hope for a time “When hongre hides his head, and plenty please the poore, / And niggerdes to the nedy men, shall never shut their doore.” Davy also yearns for the fulfillment of the “abbot of Abingdon” passages, when “Rex doth raigne & rule the rost, & weeds out wicked men,” the first three words forming a refrain that recurred throughout the pamphlets by Churchyard and his opponents in the wake of Davy Dycars Dreame.35 From beginning to end, the Davy Dyker sequence uses as its touchstones the two modes of prophecy whose prominence had been signaled by the producer of CUL Gg.4.31 a few decades earlier. And, while Churchyard was indeed a Protestant who supported Edward VI, his broadsides barely engage with religious factionalism. To call them “Protestant” on account of his religion, then, would be not so much wrong as beside the point.

A mid-sixteenth-century compilation of political prophecies, BL MS Sloane 2578, firmly places Piers Plowman's “prophecies” within a Protestant tradition, but even here critics have exaggerated its reformist characteristics. The Sloane compilation includes a number of anti-Marian passages, toward the end of which the “monks' heads” and “there shall come a king” prophecies are not juxtaposed, but combined, in a passage first brought to light by Sharon Jansen (fols. 107v–108r):

Then I warne you workmen, werke while ye maye. For hunger hitherward hastethe to chaste us. Eare v. be fulfilled suche famen shall arise. Thurgh floodes & fowle wether frutes shall fall, & so Saturne sende you to warre, when you see the same amys & too monkes heddes. / And a maide have þe maistery, & multeply by ryght, then shall deathe withdrawe, & derthe be justice, then davy þe dygger shall dye for hunger. But if God of his goodnes graunte us a truce. For þer shall com a kinge & correcte, you religious, and beate you as þe byble telles, For breakinge of your rule and nunnes munkes & Chanons, & putt þem to þe penance, Ad pristinum statum. / Finis.

Today we recognize this as a combination of two passages from Piers Plowman, B 6.321–31 and 10.322–5, but it is not clear that the Sloane copyist did.36 The existence of a longstanding tradition, most likely oral in character, that juxtaposed these passages suggests as much. So do his presentation of these lines in prose (others, even on the same page, are in verse) and the presence of unique variants that, as Pearsall observed, point to memorial reconstruction.37

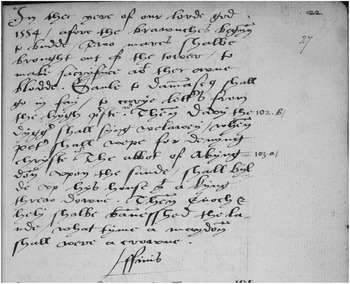

Wendy Scase observes that “Jansen did not however notice that these are the same two groups of Piers lines that underpin Dauy Dycars Dreame.”38 But neither Jansen nor Scase noticed an instance of this combination much closer to hand, in Sloane 2578 itself, to which an early reader or the scribe drew attention by writing “102.b” and “103.a” in the right margin, directing readers to the Piers Plowman lines (i.e., the modern 107v–108r), and “22.a” (modern 27r) next to that item in turn (see Figure 8).39

In the year of our lorde god 1554 / afore the brawnches begyn to budde / Two mares shalbe brought out of the tower / to make sacryfyce with ther owne blodde. Saule to Damascus shall go in fay / to carye letters from the hygh preste. Then Davy the dygger shall syng welawey / when Peter shall wepe for denyng chryste. The abbot of Abyngdon upon the sande / shall bylde up hys house þat a kyng threw downe. Then Enoch & hely shalbe banesshed the lande / what tyme a maydon shall were a crowne. / Finis

Figure 8 Another “Davy the dykar” poem.

These quatrains appear in this form in B.L. MS Harley 559, fol. 33v, where they are stanzas three through five; another, six-stanza version is extant as well, even within Harley 559, at fol. 11r.40 That this prophecy is so much more faithful to the item's other appearances only underscores the probability that the Sloane Piers Plowman lines were, by contrast, originally copied from memory, either by this compiler or by the originator of the lines in an earlier exemplar.

Witnesses to his sermon said Brynstan cited scripture in support of his description of the king's title as Supreme Head of the Church; it seems likely, this body of evidence suggests, that Piers Plowman, too – or instead, as suggested by “I am your aller heyde” – made an appearance in Glastonbury, even if it was not cited as such. The Winchester Anthology's divergence from the received B 6.328 offers further support: rather than the standard claim that a maid shall “have þe maistrie,” Winchester alone says instead she will “bere rule & reigne,” and like the king will come “with crowne the commune to reule.”

Robert Crowley and the face of a prophecy

Regardless of how Davy and the abbot got into the Sloane collection, they do not manifest an inherently Protestant Piers Plowman of their era. Whatever such credentials attach to these items are counterbalanced by the equally staunch Catholic credentials of the Winchester text. Neither CUL Gg.4.31 nor Davy Dycars Dreame suggests that Piers Plowman's “prophecies” were taken to be inherently reformist in the Tudor era. It is important to maintain this perspective for a historically informed account of the most famous sixteenth-century juxtaposition of the “monks' heads” / “there shall come a king” modes, Robert Crowley's, the sixth member of the tradition traced here. Crowley cites only two passages in his preface to his 1550 editions: the opening, which exemplifies alliterative meter, and the “hunger prophecy.” Unlike the other versions, this instance distances Langland from the passage's sentiments:

As for that is written in the .xxxvi. leafe of thys boke concernynge a dearth then to come: is spoken by the knoweledge of astronomie as may wel be gathered bi that he saith, Saturne sente him to tell. And that whiche foloweth and geveth it the face of a prophecye: is lyke to be a thinge added of some other man than the fyrste autour. For diverse copies have it diverslye. For where the copie that I folowe hath thus:

Crowley's conclusion that the verses are not Langland's rests on the dubious logic provided by what we would now call the C-text version of the passage.41 Still more remarkable is the fact that he feels compelled to say this at all: his Langland would not indulge in such puffery. In his second and third editions, seeming to have forgotten his earlier claim that this passage had the face of a prophecy and thus must have been an intrusion, Crowley newly annotates it so as to underscore his refutation of this tradition: “This is no prophecy but a pronostication.”42

The standard explanation of Crowley's disattribution of the “monks' heads” passage from Langland is that “the reader is not to read this text as if it were a prophecy of Merlin, or one of the other medieval prophetic texts sixteenth-century reformers associated with paganism.”43 But only ten or so of Piers Plowman's 7,000-plus lines might court such a response: why, then, is Crowley so worried?44 And why does he continue immediately with a denial of any prophetic status to the non-Merlinesque “there shall come a king” lines?

Nowe for that whiche is written in the .l. leafe, concernyng the suppresson of Abbayes, the Scripture there alledged, declareth it to be gathered of the juste judgment of God, who wyll not suffer abomination to raigne unpunished. Loke not upon this boke therfore, to talke of wonders paste or to come but to emend thyne owne misse, whych thou shalt fynd here moste charitably rebuked.

The passage is very odd, especially given the general assumption that Crowley exemplifies this era's belief that Langland was a prophet. This passage suggests exactly the opposite: about the “king shall come” lines Crowley says merely that Langland has cited (“alledged”) a scriptural passage to the effect that sins will be punished. Indeed he adjures his readers not to look for wonders “to come” in these pages: as James Simpson observes, “Despite some annotations that point to Piers as prophetic, Crowley himself was less inclined to read the poem as prophecy, and more as offering a powerful example of courageous protest, whose force was still relevant.”45

Crowley's careful account of his quest for the poet's identity, Thomas A. Prendergast argues, is intended primarily to promote this dissociation. Such prophecies were often “craftily hidden in some old stonie wall, or under some altar, or in some ancient window,” as the physician John Harvey (whose brother Richard owned Owen Rogers's 1561 edition of Piers Plowman) wryly noted: “The text of Piers, on the other hand,” says Prendergast, “is manifest and actively sought – Crowley endeavors to gather together ‘such aunciente copies’ as he could come by.” So too the insistence on dating the poem, and on the ancientness of his sources, was a pre-emptive strike against any accusation of “newfangledness” of the sort that John Brynstan found in the Reformists: “the claim is that the texts that illustrate the existence of the new religion are not ‘new’ either.”46 What Prendergast says would apply as well to the very form of Crowley's Piers Plowman, which, I would suggest, constitutes a response in opposition to, rather than exemplification of, an oral tradition of the “prophecies of Piers Plowman.” In particular, the bookish paraphernalia of his edition – its preface and apparatus of marginal commentary – attempt to re-textualize Piers Plowman in the face of its wild (and oral) ride from Langland's pen to the House of Fame, on which route it had visited the Mum-author, John Brynstan, and Cromwell's interviewees, and, eluding Crowley's grasp, would soon head for the Sloane compilation. Crowley, in sum, attempts to restore these free-floating passages about monks' heads and chastizing kings to their scripted, non-“prophetic” contexts.

The phenomenon against which Crowley's performance calls to be interpreted left very few traces behind, and would still remain hidden if the newly uncovered instance in the Winchester Anthology had not brought it into focus. We can now go much further than the claim that Crowley's readers are not to see Piers Plowman in the light of Merlin's prophecies: nor, it seems, are they to read it as if it were the Piers Plowman whose textual remnants survive in the amalgamation of prophecies in Davy Dycars Dreame, the two items in the Sloane collection, and Brynstan's productions. Crowley is rescuing Langland from “Piers Plowman”: these words are no longer prophecies uttered by that gnomic character, as in the Winchester Anthology, but instead the intelligent prognostications by the historical poet Langland (when concerning disendowment), and, at least when Crowley remembered, intrusions from someone else (when making wild claims about monks' heads and the sun amiss).

My proposal calls for a revision of the notion that “Crowley's reformist interpretation” of the poem “marks the culmination of the Piers Plowman apocrypha that had grown up during the previous two centuries,” which has served in effect as the default sixteenth-century instantiation of the poem.47 We have already seen that the generally accepted relationship between Davy Dycars Dreame and Crowley needs to be reversed; and even the Sloane compilation, pace the beliefs of a number of critics, bears no trace of his influence.48 The one intriguing textual variant shared by the (pre-corrected) Winchester lines and the preface (but not text) of Crowley's third edition, “three” for “two,” is certainly coincidental.49 And, while Bryan Davis remarks in passing that the compiler of the sixteenth-century Cambridge manuscript “constructed a reading of Piers Plowman that dislocates the poem from its tantalizingly topical context and shifts it closer to the context of reformist, prophetic rhetoric into which the poem was inserted by Bale and Crowley,”50 we should now accept the logic against which this observation is working: that manuscript might be “prophetic” in other ways, but not this one. Crowley was looking back at that document – literally, that is, for he seems to have consulted it once before preparing his first edition, and again when preparing the second edition51 – but its producer was not looking forward, or even, probably, outward.

The revision of the post-Reformation Piers Plowman should extend to our assessment of its religious affiliations. Reformers might have embraced the figure of Piers the Plowman, but those engaging with the poem in which he first appeared did not necessarily adopt such an approach. Crowley is not an exception to this trend: the standard narrative has it that he was following the lead of his collaborator and colleague John Bale, who wrote, “In this erudite work [sc. Piers Plowman], beside the various and delightful allegories, he prophesied many things, which we have seen come to pass in our own days,”52 but as Larry Scanlon has pointed out, only 15 of the 495 glosses, 3 percent, of Crowley's third and most heavily glossed imprint are explicitly anti-Catholic.53 Nor is his text itself, as opposed to the apparatus, any more “reformist” than Langland's own, as R. Carter Hailey conclusively demonstrates.54

Catholic Piers Plowman in the sixteenth century

This absence of a strongly Protestant Piers Plowman right where we thought it to be not only present, but predominant, is not as surprising as it might appear; John Brynstan is not the perverse anomaly he would have been were the assumption that the sixteenth century was home to “Piers Protestant” and no other version of the poem accurate. As the only “striking exception” to what she claims to have been the poem's otherwise exclusively reformist reception history from 1400 to 1600, Anne Hudson identified, from the 1530s or later, The Banckett of Johan the Reve unto Piers Ploughman, Laurens labourer, Thomlyn tailyer and Hobb of the hille with other, in BL MS Harley 207.55 Yet there were others, in addition to Brynstan. In 1613 one Andrew Bostock entered marginalia into his copy of Crowley, “return[ing] to the traditional interpretation of Piers Plowman as an orthodox appeal for reform within the established church.”56 Nor, of course, was Sir Adrian Fortescue any stooge for Henry VIII in making his copy in 1532 (see note 28). And New Haven, Yale Beinecke MS Osborn a.18, a handwritten pamphlet of the 1580s, purports to offer Piers Plowman's consolation to Catholic martyrs, which a later Protestant hand describes instead as a way to indoctrinate papists in the ways of treachery. The Winchester Anthology was just one of many homes of a Catholic Piers Plowman in the era of the Reformation.

Those two monks' heads played no less prominent a role in the reception history of Piers Plowman than did the real-estate losses of the poor abbot of Abingdon: the “prophecies” that sixteenth-century audiences in particular embraced were not the sole provenance of the latter mode. We need, as Richard K. Emmerson has commented, “to trace the reception of Piers Plowman diachronically, to place the later ideological readings by Crowley and other Protestant polemicists if possible within a more continuous tradition. We need to determine the extent to which contemporaries and near contemporaries received the poem as a species of prophecy.”57 We need, in other words, readings of late medieval and early modern culture that do not advert to a Langland archive that tells us what we already “knew”: that from 1530 Piers Plowman was Protestant. For the tradition tracked here is one against, not within, which Crowley sought to place his work. This is a haunted land with which critics today are about as comfortable as was the author of Mum and the Sothsegger or indeed Cromwell himself; we would rather discuss the politics of ownership than celestial portents and visions of headless bodies or bodiless heads.

To ignore those Merlinesque passages, though, is to misrepresent the sixteenth-century Piers Plowman not because a focus on Crowley is partial, but because they are so crucial to his enterprise to begin with. The full respect that all these figures accord the monks' heads passage, quite apart from its context in the narrative of the “Visio,” might result in a picture of a poem far from the literary full-length masterpiece we usually study, and that the producer of Gg.4.31 copied and Crowley edited. But both Mum and the Sothsegger and Piers Plowman itself suggest that this disembodied collection of texts, whether or not prophesying any wholesale reform of the church, was not an invention of a Tudor pamphleteer, or a monk-turned-apostate-friar, or a political-prophecy obsessive, or an indexer/cross-referencer/copyist, or a reformist “rescuer” of the poem. Rather, these texts were always present in Piers Plowman, newly brought to the light of the sun amiss, away from the gaze of the poem's archons.