Chapter 6 William Dupré, fabricateur: Piers Plowman in the age of forgery, c.1794–1802

Fabricateur, s.m. a fabricator; a manufacturer. This word was only used to imply a forger, or a coiner, or a fabricator of counterfeit money; but now means one employed in lawful and allowed fabrications or works.

John Urry, John Taylor, and William Burrell might well have been passionate about Piers Plowman, but not because of any innate love of poetry. We would hardly expect as much from readers of their era. Such passion would wait for Romanticism, another movement that has seemed wholly separate from the creation of the Langland archive. And yet it is Will and the medieval inhabitants of Langland's world that the 20-year-old Robert Southey, future poet laureate and friend and brother-in-law of Coleridge, is talking about here: “never was individual placed in a situation more important – never did man experience more heart-rending scenes. they are past – the energies of my mind have been all exerted & I look back with astonishment at what they have endured.” In October 1794 Horace Walpole Bedford, younger brother of Southey's best friend Grosvenor Bedford, had gifted him a copy of Crowley's second 1550 edition, and Southey is here following up, on November 12: “in the tumult of emotion I have neglected to thank you for Piers Plowman – or if I did thank you, have forgotten it.”1 A later owner of this volume, the great bibliographer and Shakespearean W. W. Greg, explains on its flyleaf that “it was in Oct. 1794 that his aunt, Miss Eliz. Tyler with whom he lived, turned him out of her house on account of his engagement to Edith Fricher” – sister of Coleridge's future wife – “whom he married the next year.”2

By this point it is no surprise to come upon a need to turn to the material archive, to such documents as this letter or Southey's copy of Crowley's Vision of Pierce Plowman, to make sense of individuals' careers or their larger-scale historical and literary contexts. Other stories, which take shape across the boundaries of such periods, are manifested in those old books themselves: Southey's copy had belonged to Bedford and any number of others over the previous 244 years, would later be Greg's, and now enjoys the company of the former Sion College manuscript in the collection of Toshi Takamiya, in Tokyo. Likewise the best introduction to a more extensive and fascinating picture of Piers Plowman in the Romantic age is via the world of antiquarian and classical scholarship that occupied Chapter 5, so foreign to the passion of Southey. It occurs in John Taylor's Rogers, now Bodleian 4° Rawlinson 274, which brought with it the work of another John Taylor – in fact, signaled its association with an item whose own history would see it become among the most celebrated and controversial portraits in England, one at the heart of the late eighteenth century's self-definition as site of “authenticity” above all.

Responding to the signature of Robert Keck on the title page, Dr. Taylor inscribes, as would Greg, a mini-biography of this notable earlier owner into the copy: “From Mr. Rob. Kecke of ye Temple, who had ye Origin did Vertue copye his print of Shakespeare.” The “Origin” is the painting that would become known as the Chandos portrait, inaugural accession of the National Portrait Gallery, reproduced on the covers of innumerable books. Keck attributed the painting to one John Taylor, but in his day, as the later Dr. Taylor of St. John's College reports, it served as the original from which George Vertue had recently made an engraving (see Figure 14). Whatever attraction the coincidence of names might have held for Taylor, the Shakespeare connection would have been difficult to look past. “The eighteenth century,” as Samuel Schoenbaum remarks, “had a rage for Chandos.”3

By the end of the century, though, the situation had altered dramatically in ways that marked a decisive break between the respective eras of John Taylor and of Robert Southey. The Chandos portrait and its most prominent advocate, Edmond Malone, became embroiled in heated controversies over questions of authenticity and forgery, concepts, at least with regard to Shakespeare, that are themselves products of the Malone–Southey era. This is when the revolutions in France and America “brought a new order of subject into being,” as Margreta de Grazia says, one that was “cut off from past dispensations and dependencies,” among whose manifestations was the very discipline of literary studies as conceived by Malone himself.4 It was in this unsettled milieu, rife with revelations of scandalous forgery as with triumphant scholarship, that a remarkable and heretofore unread chapter in the history of Piers Plowman – that of its first modernization – was written. It is a story to which Southey will return in 1802, as defender of the legitimacy of Thomas Chatterton (1752–70), also known as “Thomas Rowley,” supposed medieval poet. In the meantime, the Chatterton/Rowley episode's role in a scandalous novel of 1780 had, over a decade later, inspired the young William-Henry Ireland to fabricate, in the term's most literal mode, Shakespearean documents, even a notorious play. The disappearance from modern critical consciousness of the fabrication of Langland by one William Dupré, distant disciple of Chatterton, is the primary, if implicit, topic of this chapter, one that necessitates a detailed rehearsal of these fascinating episodes, beginning with the arguments generated by the fall of the painting in Robert Keck's collection, the “Chandos portrait” of Shakespeare, when he also owned a Rogers Vision of Pierce Plowman.

Edmond Malone and the authentic Shakespeare portrait

“This is the portrait of Shakspeare, which has been so frequently engraved, and to which the fancy of each succeeding engraver has added every conceivable variety of feature, expression, and dress,” wrote James Boaden in 1824 of Chandos. “No picture within the last hundred years has been more frequently copied.”5 All this variation induced Edmond Malone to seek out the original from Lord Chandos in 1783, upon which he obtained permission to commission Ozias Humphry to draw it afresh, in crayon, from the original.6 Chandos had overtaken the Droeshout engraving, featured on the title page of the First Folio, as the image of choice for editions in Malone's century. But the rage for Chandos, perhaps inevitably, divided itself. In the early 1790s a rival appeared on the scene, today called the Felton portrait, whose “close-up focus on the egg-shaped dome,” says the cataloguer of the Folger's paintings, “makes him seem an inhabitant of an extraterrestrial dimension.”7 George Steevens became its greatest champion, and unsurprisingly “employed the picture as a weapon with which to bash his rival Edmond Malone, who had done so much to support the claims of the Chandos Portrait as being from the life.”8 Another of Steevens's weapons was mockery of the Chandos portrait's pedigree by suggesting that “the possession of somewhat more animated than canvas, might have been included, though not specified, in a bargain with an actress of acknowledged gallantry,” a mean reference to the story that Keck had purchased it, and more besides, from the great actress Mrs. Barry for 40 guineas.9

History has been kinder to Malone's candidate, still deemed “the most probable contender to be a portrait of Shakespeare made in his lifetime,” than to Steevens's, now considered a fake, perhaps promulgated by that sly editor himself.10 These claims and counterclaims regarding authenticity and forgery, intimately related to the issues with which editors like Malone and Steevens grappled in their work on the Shakespeare text, came to a head only a few years after the Felton portrait reached the public eye. Indeed, Boaden had said: “There is however something of a strange coincidence” in what was known about the provenance of the Felton portrait:

Mr. Wilson receives in 1792 from a man of fashion, who must not be named, a head of the poet, dated in 1597, and endorsed Guil. Shakspeare. About the same time, were received sundry deeds, letters, and plays of Shakspeare from a gentleman, who in like manner was not to be named. And they abounded in the hand-writing of Elizabeth's reign, and also exhibited the poet's name with the recent orthography of the Commentators. I do not know that this picture might not have been intended to appear among the infinite possessions of the nameless gentlemen.11

Boaden is of course alluding to the notorious forgeries that a young man named William-Henry Ireland perpetrated in 1795, his own father being the most immediate victim. The coincidence is indeed remarkable. It was Malone, in his Inquiry into the Authenticity of Certain Miscellaneous Papers . . . (1796), who exposed the fraud in devastating fashion:12 but one aspect of the aftermath was quite unexpected in a way that would have a direct, and unsettling, impact on the story told in this book. This was George Chalmers's Apology for the Believers in the Shakspeare-Papers of 1797, which responded to Malone's exposure of the scandal. Chalmers took umbrage not at Malone's conclusion, but at the assumption that, because the documents were forgeries, the faith of the believers was therefore fallacious. In sum, says Chalmers, Malone “might, with a good grace, have told the believers; ‘I will admit the propriety, and the truth, of your positions; yet, will I demonstrate, that your belief is unfounded’”: but “by conceding none of these points to the believers” he instead acted in bad faith.13

Early in this extraordinary diatribe, Chalmers catalogued the merits of the Felton portrait, which had failed to convince Malone despite his supposedly objective approach to evidence:

The oaken board, whereon the gentle Shakspeare is pourtrayed; the inscription of the poet's name, by a contemporary hand; the corresponding likeness between the original painting and the existing print of Droeshout; the corroborating evidence of Ben Jonson, who had compared “the figure” with the man; all concur to evince the genuineness of this ancient painting. Were we to consider the argument, without indulging prepossession, or referring to connoisseurs, the authenticity would be readily acknowledged by all judges of evidence, except by those, “who allow to possibilities the influence of facts.”14

Against this, Malone's devotion to Mr. Keck's dubious Chandos portrait comes across as bald hypocrisy, given his attacks on the “believers” for supposedly not following Cartesian logic: “Yet, Mr. Malone perseveres, in grappling to his heart, with hooks of steel, ‘the unauthenticated purchase of Mr. Keck, from the dressing-room of a modern actress:’ For, it is a part of his philosophy to allow the possibilities the influence of facts” (9).15 The ferocity of this rhetoric concerning a few brush-strokes demonstrates the ways in which what is included in the archive, so often an arbitrary process, can determine the overall shape of a discipline. For what have these portraits to do with Shakespeare's oeuvre? Nothing apparent. But no one would suspect as much from the passion with which Malone, Steevens, Chalmers, and innumerable others invest the question. That passion could not help but rub off on outsiders who could only wish to have their own voices heard, even if only to be scorned.

William Dupré and the Shakespeare forgeries

Over the first half of 1802 readers of The Monthly Magazine were treated to what must have seemed a refreshing respite from all the unpleasantness of the previous decade: an entertaining and informative series of letters, which one William Dupré of Poland Street, Soho, translated from the French originals by Brunetto Latini, this time in the possession not of an unnamed gentleman but of Dupré himself. Most of these letters were addressed to Brunetto's fellow Italian poet Guido Cavalcanti, with a few to Charles, count of Anjou and Provence. They were composed during a visit to the court of Henry III of England, and tell about this foreign land's customs, literature, and scientific knowledge: the giraffe kept in the Tower of London, the poetry of a Cistercian monk, a conversation with Roger Bacon about the mariner's compass. Brunetto had his finger on the pulse of medieval England.

But it was too good to be true. In December, five months after the ninth and final letter, the magazine ruefully announced: “Mr. Dupré, the gentleman from whom we received the communications respecting Brunetto Latini, has thought proper, though not till after detection, to confess that he has been imposing upon us, and that, in the supposed letters of that person, he only meant to give a picture of English literature and manners, as they existed in that period, in imitation of the French Anacharsis”:16 the reference is to Jean-Jacques Barthélemy's Voyage du Jeune Anacharsis en Grèce, first published in 1787 and quickly translated into English in many editions, which did the same for the ancient Greek era. Notwithstanding this correction, and Mario Esposito's publicization of the episode in a prominent scholarly journal in 1917, “Brunetto”'s account of his interview with Bacon, in particular, has often been cited as if it provided authentic historical evidence.17 In 1930 Esposito expanded on the account, noting that Dupré's sources were manuscripts once in his possession that are now part of the Bodleian Library's Douce collection.18 Dupré must be counted as a major, and unheralded, manuscript collector of the his era. That, though, was all that anyone knew about the episode until Claudio Giunta's 2008 essay “Il triste destino di William Dupré, falsario,” based on his discovery of a cache of letters from the 1790s, which fill out the background.19

In 1795, so Giunta revealed, Dupré wrote to his former supervisor in the army that he and his son wondered whether they might “flatter Ourselves that Our Service & Sufferings will be attended to” by him: “I have had such good proofs of your humanity & benevolence that I can hope everything from You, Sir.”20 Two years later, writing from City Coffeehouse in Cheapside, he offered three manuscripts for sale to the earl of Liverpool: two on which he would rely heavily for his forgeries (now Douce 227, containing the laws of Oleron, dated 1344, and Douce 319, a large folio volume containing Brunetto's Tresor), and an unidentified Italian manuscript called Trattato del Commercio.21 While it might seem odd to have targeted a mediocre politician better known today as father of a long-serving prime minister, Liverpool “was an excellent classical scholar,” said the Quarterly Review in 1815, “and possessed as great a variety of reading as perhaps any of his contemporaries (except only Burke).”22 And this doyen of the arts long employed George Chalmers, among whose (unofficial) duties was turning his pen against Thomas Paine, in the guise of a Francis Oldys, A.M., of the University of Pennsylvania, spelling his subject's name “Pain.”23

Another letter in Dupré's hand, also of 1797, reveals how he fell into such dire straits: during the “fatal Retreat of 1794” from French revolutionary forces, Dupré, in his capacity as director general of hospitals in the duke of York's army during its French campaign, “was mad Prisoner by the French with my Son, and a Young Man belonging to the Hospital, & marched to Boisle duc, being stripped of a Sum of Money I had necessarily with me to bear our Expenses ’till we joined the Army.” After three months’ captivity they returned to England in 1796, where he found himself “unhappily without employment,” in which situation, “the only Hope remaining to me, is, that I may find some beneficent Character who may put me into Employment which may procure me Bread.”24

The “beneficent character” to whom Dupré addressed this appeal was none other than Chalmers, in the very year that his Apology for the Believers in the Shakspeare-Papers appeared. The letter does not mention the Ireland forgeries, but there can be little doubt that Dupré intimately knew the case, and especially Chalmers's contributions. Everyone else did, after all, even those who did not seek his patronage and go on to perpetrate a mode of fakery that the Apology seems to value as highly as the real thing. The “believers,” Chalmers writes, acknowledge the spuriosity of Ireland's forgeries,

yet; they do not admit Mr. Malone's principle, that our whole Archæology may be misrepresented, for the purpose of detecting a literary fraud; nor, do they allow, that the said republic ought to be invaded in its limits, or disturbed in its quiet, by his discharge of this inundation of mistempered humour, for the gratification of an indiscreet zeal.

It might seem surprising that a public figure not only expressed no embarrassment at having been taken in by the fakes, but also championed the “quiet” of the “republic” of those believers over and above the rigorous philological sleuthing of Malone. Yet Chalmers does present the case on the basis of a certain logic: that “the believers, were led into their error, by system, while the inquirer himself is only right, by chance” (33); that his opponent is “right by chance, rather than convincing by argument” (123), “wrong by system, and merely right by accident” (220), and so on.

The aspect of Chalmers's argument that, I suspect, emboldened Dupré five years later manifests itself in the peculiar combination of Malone-like logic with the rhetoric of belief and faith, which it is Chalmers's consolation to recognize as the foundation of the literary archive. The believers hold their hands on hearts in supporting the notion that the accused forger “comes into court with every presumption in his favour; with every probability of innocence, for his protection; with every inducement, under a want of proof, for his acquittal: But, the public accuser, by supposing what he ought to prove, . . . raises a suspicion only, that the accused may possibly be guilty” (215). Chalmers's claim, in short, is that Malone is inhuman in his resistance to the riches of possibility, to faith itself: “The other concomitant of scepticism is hardness of heart” (23). The believers, Chalmers implies, embody the Pauline virtue of faith, where the skeptic shows his hard-heartedness: “Mr. Malone is induced by his scepticism to insist, that the prettye verses of Shakspeare never existed; because he has never seen them; and he is incited by a peculiar logic to argue, that whatsoever does not appear to him has never existed on earth” (39). By contrast, even though they ended up being wrong, the believers can take heart in the fact that “the profession of faith is strongly supported by external evidence” (219).

To Chalmers, it matters little whether the object of the believers’ faith was factual: for it was true. Shakespeare did compose the sonnets for Elizabeth I even if the letters to that effect in Ireland's papers turned out to be fraudulent. Chalmers here defends the mode of scholarship, one as interested in the cultural capital of Shakespeare as in the facts of his life and career, that had held sway throughout the eighteenth century but that is now, under threat from Malone himself, collapsing. This is the subject of Margreta de Grazia's study of Malone's 1790 apparatus.25 Did Shakespeare speechify in his father's butcher shop while slaying a calf? Poach a deer from Sir Thomas Lucy, then post a satirical ballad on his gate as revenge for his punishment? Die of a fever contracted on a night of serious alcohol abuse with Drayton and Jonson?26 Editors before Malone did not concern themselves too much over the factual basis or otherwise of these stories, which served, rather, as evidence of Shakespeare's status as generator of narratives that were external to his own literary productions. Such tales were just part of the archive, part of the phenomenon to which the editions bore witness, not, as Malone later determined, extraneous falsehoods that impeded access to the authentic genius. Chalmers does not discuss any of those famous tales, but his approach to Ireland's papers is very much in keeping with his predecessors’ to them: if the story seems plausible, it should get the benefit of the doubt rather than be subject to the antagonism of a hard-hearted skeptic.

In the Malonean mode of scholarship, the individual rises above the community, and from the present vantage point can pass over the vicissitudes of intervening history to gain direct access to the authentic original. De Grazia aligns this mode with the appearance of a new political subject arising from the revolutions in France and America in this era (see note 4). Insofar as the rise of “the subject” has long been taken as a marker of the early modern era's divide from its medieval past, it would not be pushing the case too far to say that with the American and French Revolutions – and with Malone's 1790 Shakespeare – modernity finally arrives. It does so, however, without George Chalmers's endorsement. (He first attracted Liverpool's attention via his authorship of pamphlets attacking Burke's conciliatory approach to the American colonies.)27 Chalmers insistently celebrates the community of believers, who would rather, if put to the choice, have an openness of heart than a knowledge of fact; he would rather remain in the premodern world from which even such recent editions of Shakespeare as those by Rowe and Pope emanated.

This is the world that William Dupré, too, celebrates, more explicitly than does Chalmers, for he conjures thirteenth-century England, and does so from ancient manuscripts. We do not know how he came upon these items, and his attempt to sell them to Chalmers's patron obviously failed. But the very fact of his ownership, and the care with which he studied them, speak of a devotion to understanding premodernity rivaled perhaps only by that of antiquarians like Dr. John Taylor and Richard Gough. Dupré served in an army opposed to the French revolutionary forces, and his continual search for patronage, from Liverpool and Chalmers at the least, smacks of an acquiescence to, if not active desire for, a social position of fealty to his (Tory) superiors. Yet the primary motivation for the “Brunetto” letters was money: “It is hoped that every lover of ancient literature will contribute what assistance he is able towards restoring this restorer of good learning in the thirteenth century.” The translator is in especial need of support because of the “difficulties, which an obscure man, who happens to be fond of letters (perhaps, too, engaged in literary pursuits, and it may be, moreover, in circumstances that are narrow and confined;) labours under from the want of a public-library in this great metropolis”: a stark reminder that the material archive is a site of privilege.28 But if money and pity were the ultimate goals of the “Brunetto” letters, the imaginative use to which he put his manuscripts came from a different place, one whose path was lit by Chalmers's magisterial, and bizarre, backlash against Edmond Malone in 1797, which itself was only the most recent and immediate model for Dupré's challenge to the dominance of the factual over modern historical consciousness.

Love and Madness and Middle English

In the March 1802 Monthly Magazine, as Giunta observed, “Brunetto”'s second letter is immediately preceded by a note from that devotee of Piers Plowman with whom this chapter opened, Robert Southey, explaining the delay of the appearance of his edition of the Chatterton/Rowley poems. An insufficient number of subscribers had prevented publication, a gap whose closure would benefit both the world of letters and the memory of the lamented poet: “The merit of his works is now sufficiently known: hitherto they have been published only for the advantage of strangers and pilferers; they are now collected with the hope of rendering the age of his sister comfortable.”29 That sister was Mary Newton; the pilferer, Herbert Croft, who stole Chatterton's correspondence from her and proceeded to publish it, together with Newton's desperate letter seeking the return of the correspondence, in his epistolary novel of 1780, Love and Madness.30 The letter succeeded, the edition appearing the following January and netting Chatterton's sister, Mary Newton, over £300.31

Dupré was surely familiar with the story, and poetry, of Chatterton, by this point a Romantic hero, whether via the poetry itself or via the work that Southey cannot bring himself to mention, Croft's Love and Madness, the “very entertaining work” that would likewise have a profound effect on William-Henry Ireland.32 Love and Madness told the story of the notorious murder of Martha Ray (“R.”), a popular singer and mistress of the earl of Sandwich, by a lovelorn vicar, James Hackman, “H.” The latter is obsessed with forgers, and before eventually killing R., keeps writing her about them, with pride of place going to Chatterton, for whose sake, he asserts, “the English language should add another word to its Dictionary; and should not suffer the same term to signify a crime for which a man suffers the most ignominious punishment, and the deception of ascribing false antiquity of two or three centuries to compositions for which the author's name deserves to live forever.”33

Yet it is not just in its account of Chatterton, I would argue, that Love and Madness was so important to Dupré. For one, as Brian Goldberg has argued, “Croft was the type and form of the establishment writer: dependent on the patronage of the Church and the support of a gentlemanly readership, Croft perceived his interests as directly tied to the fate of the landed oligarchy.”34 Likewise Dupré, if “army” is substituted for “Church.” Neither of these authors was a creature of the new professional writing class exemplified by Robert Southey, in the service of which Chatterton's death was seen to be something of a martyrdom. Also, two features of Love and Madness are directly pertinent to the “Brunetto” forgeries, and provide the context for Dupré's work on Piers Plowman: the employment of the epistolary form for what was a fictional account of a historical event, which is what Dupré saw himself as presenting, even if the history was far distant and had little of a scandalous nature; and, more immediate, the presentation of primary documents within the letters of the novel.

Where Croft perniciously printed the manuscripts of Chatterton and his sister within a letter of “H.,” “Brunetto”'s letters introduced to modern readers two authentic Middle English works. The first and final letters between them provide the fourteenth-century debate-poem Ypotis, which “Brunetto” says is a translation into English of an Aesopian fable that he heard on the ship to England.35 The other is “a specimen of prose,” The Abbey of the Holy Ghost, which he says he is sending because Guido had been “so well pleased with the English poetry which I sent you”:

I now send you some extracts from a beautiful composition of a monk of great piety and learning. It contains the History of the Fall of Man and his Redemption through Christ, under the form of a well-contrived allegory. It begins thus, “Here is the Book that speketh of a Place that is called the Abbey of the Holy Gost the whiche schulde ben founded in clene concience.”36

While it might be easy today to allow the scandal of the forgery and the centrality of matters Italian and scientific to dominate our assessment of the episode, Middle English literature is at the heart of these letters.

Dupré's source for both these works was a manuscript in his possession, now Bodleian MS Douce 323, unmentioned in the letter to Liverpool five years earlier. It also contains an A version of Piers Plowman, a poem whose absence from “Brunetto”'s letters is surely the result of its relative canonicity, even in this era before Whitaker or Wright had published their editions. Readers of periodicals like The Gentleman's Magazine or The Monthly Magazine, not least Robert Southey, were too familiar with Langland's poem, both from the sixteenth-century print editions and from anthologies and literary histories such as those by Elizabeth Cooper (Muses Library, 1737), Thomas Warton (History of English Poetry, 1774–81), and Joseph Ritson (English Anthology, 1793–4; Bibliographia Poetica, 1802), for it to pass as a previously unknown showcase of thirteenth-century English piety.37 What Dupré did instead is perhaps much more interesting, and should secure him a place as one of the liveliest figures in the annals of Langland scholarship.

Francis Douce adds this note to MS 323: “I purchased this Ms. of M. Dupré who had intended to publish a metrical version of Pierce Plowman modernized, of which I have preserved a specimen in this volume. The rest he would not part with” (fol. vir) – a tantalizing claim that leaves open the possibility that more remains to be discovered. That specimen now occupies a booklet comprising fols. ir–iiv of the manuscript, after which their new owner repeats: “The above specimen by M. Dupré of whom I purchased the MS. F.D.” The attribution of this item to someone named Dupré appears in two nineteenth-century catalogues of manuscripts in the Bodleian collection, but without mention (or, probably, knowledge) of the Monthly Magazine scandal.38 So too the inverse: Thomas Wright publicized the translation in the introduction to his 1842 edition of Piers Plowman, but did not know its provenance:

An attempt at a modernization, or rather a translation, of Piers Ploughman, was made in the earlier years of the present century, but only a few specimens appear to have been executed. The following lines, which possess some merit (though not very literal or correct), are the modern version the author proposed to give of ll. 2847–2870 of the poem. They were communicated to me by Sir Henry Ellis.

Only now, over 210 years after the composition of this translation, can it finally be confirmed that these are all products of the same episode.40 The lines Wright printed as an anonymous oddity belong to William Dupré, who in turn is the forger known to Chalmers and, later, to the readers of The Monthly Magazine, and whose account of the mariner's compass would gull Thomas Wright himself (among many others) some decades down the road.41

William Dupré's Piers Plowman

The marks Dupré left on the Douce 323 Piers Plowman bear witness to an intelligent, if not too taxing, engagement with the poem. There is “much imagination” in Will's vision of the fair field of folk (fol. 102r), he writes, and “striking Specimens of Allegorical Satire, with much Sense & Observation of Life, & some Strokes of Poetry” where Will asks the friars about Dowel at the beginning of A passus 9 (fol. 129v), judgments for which he relies on Thomas Warton. While no William Burrell, Dupré does subpunct the phrase “hold men in good lyf ” at the last line of folio 130v (A 9.87) so as to note, “halye men from hell. Edit. 1550” in the margin below, and, next to A 10.50 (fol. 132r), observes, “From hence for three folios to Thanne had wyt a wyf &c [A 11.1] seem not to be in the Edition printed in 1550.”

Plenty of others did this kind of thing, of course: what sets Dupré apart is the modernization. Modern scholars have not quite known what to make of this phenomenon. On the one hand, Vincent DiMarco excludes renderings of Piers Plowman into modern English from his Reference Guide “except when such works in their introductions or notes present critical commentary deemed worthy of admission”: the labor that goes into the translation, and the product itself, do not suffice.42 On the other, such dismissiveness is perhaps more than balanced by the achievements of scholars as distinguished as George Kane, E. Talbot Donaldson, A. V. C. Schmidt, and George Economou, all of whom have either translated Piers Plowman or commented on the difficulties and importance of doing so since the appearance of DiMarco's collection.43 As the editors of the 1989 volume of The Yearbook of Langland Studies observe, modernizations are the products of “arguably the most demanding of all critical endeavors,” especially with “a problematic work like Piers.”44 Moreover, translations “have significantly influenced critical perceptions of the poem”45 – yet this applies to neither Dupré's translation itself nor Wright's notice of it. The earliest known translation of Piers Plowman into modern English cited by modern bibliographies is Kate Warren's of 1895, based on Skeat.46

Wright's comment on its own, some forty years after Douce's work on the poem, shows that the episode was not entirely unknown in its day, though the line of transmission from Dupré to Wright remains obscure. Douce worked closely with Wright's source, Henry Ellis, at the British Museum, where they collaborated on the catalogue of the Lansdowne collection. Wright's ignorance of the provenance or author suggests that he did not see the document sewn into Douce's copy. Ellis probably took a copy from it, then, and might well have shown others in addition to Wright. It also seems probable that Dupré approached publishing houses, even if he only ever completed the surviving specimens. He was no novice on that front, having in 1801 published Lexicographia-Neologica Gallica: The neological French dictionary; containing words of new creation, . . . The Whole forming a Remembrancer of the French Revolution, which was in general well received, one of whose entries provides this chapter's epigraph.47

Dupré probably saw a serious gap in what was a thriving market of modernizations of Middle English poetry – one monopolized by Chaucer. The phenomenon began with Dryden and Pope and continued in the work of at least seventeen known and anonymous translators who, as Betsy Bowden has shown, “produced thirty-two modernized Canterbury tales during that century, plus tale links and adaptations of each other's work,” some of which appeared in The Monthly Magazine.48 Because “reception data so precise and extensive” as that she presents in her collection “is available only for Chaucer among English authors,” the existence of data regarding any other medieval poet is invaluable.49 The materials she collects provide one small instance regarding Piers Plowman that helps to explain why no modernizations of that work competed with the Canterbury ones.

This appears in “the most extraordinary rendering of Chaucer” of the Augustan era, the anonymous “Miller of Trompington, Being an Exercise upon Chaucer's Reeve's Tale,” published in 1715. “It is true that the unknown author claims to have written it thirty years before,” says Derek Brewer, “so we may be libelling the eighteenth century by attributing this version to it.”50 Brewer is exasperated by, among much else, the “long and totally irrelevant dialogue between Allen and John on the nature of translation,” which of course has no parallel in Chaucer's own poem.51 When their subject turns to “the Clink and Blank of Poetry” (847), that is, rhymed versus unrhymed verse, Allen mocks the former sort for its associations with the materials discussed in Chapter 3:

to which John rejoins:

Yet the ancients produced more than just this sort of empty rhyme: Allen, too, is able to call upon medieval precedent in responding to John's claim that “Blanks hence I prove are not the best, / They're not in use, tho’ easiest” (883–4), for Milton's choice of form was not new:

Dupré could not bring himself to be true to Piers Plowman's poetic example, perhaps because doing so would necessitate following the great stone-blind Bard's as well. And yet his choice of verse form, heroic couplets, is not as jarring as one might expect. The specimens of his modernization that survive, at least, are of passages whose content is much closer to Pope or even Benjamin Franklin than to Milton, as would have been the case had Dupré translated B passus 18. (Since he relied on Douce 323's A text rather than a Crowley or Rogers B text, that was not an option anyway.) Wright printed the opening few couplets of the first specimen, 5.107–45, the description of Coveteise in the confession of the sins episode, a Langlandian tour de force of social satire which has long been among the most popular of the poem.52 Perhaps it lacks the sharp wit of The Rape of the Lock, but when rendered into heroic couplets it at least shows that Pope might well have dipped into the Langland portion of the Rogers he famously owned.53 And in the second passage, 7.237–61, where Piers and Hunger conspire to get the penitents back to work, Hunger turns into a veritable Poor Richard:

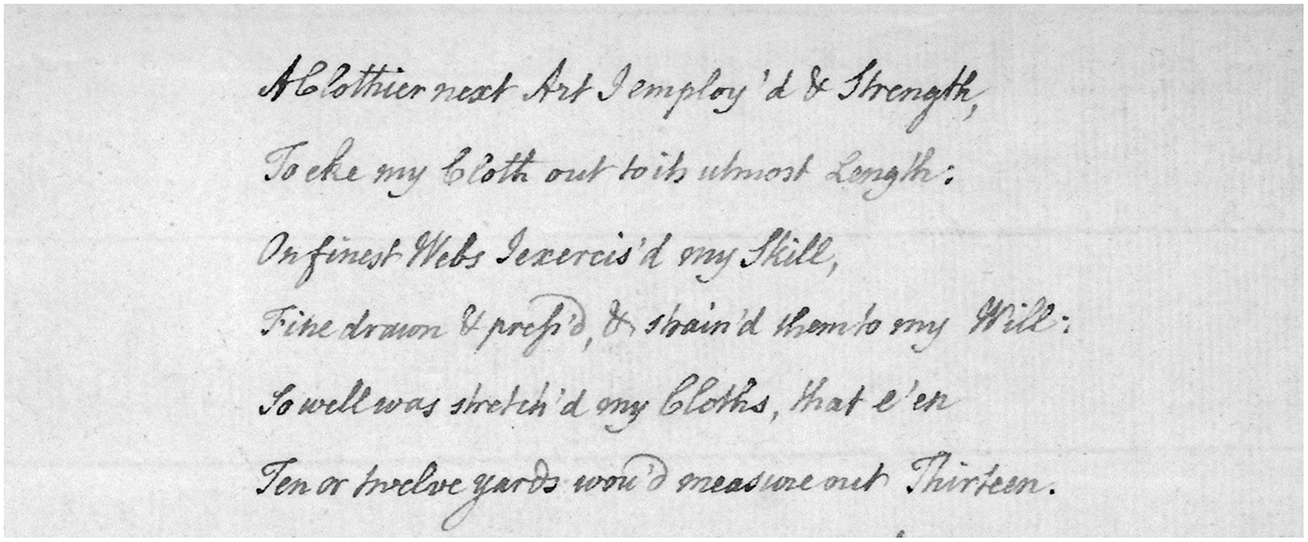

The rhyming couplet form also shares some important characteristics with Langland's alliterative long line. Dupré's lines quite often have four main stresses and a marked caesura: “Next Avarice came; but how He look'd to say” (cf. 5.107); “Rose, the Regrator, is the Name she bears” (cf. 5.140); “Well know I, Hunger says, their Griefs to heal” (cf. 7.241). Wright judged the performance “not very literal or correct,” but he had a different poem – the B version – in front of him, and also had a vested interest in playing down achievements of the recent past. In any case, even where Dupré does seem to stray, it is difficult to blame, even to keep from praising, the results. Where his (mangled) copy read, “But yf a lous coude lepe I may it not trowe / he schulde wandre on þat walssh Scarlet so was it þred bare” (5.112–13; fol. 118r), the modernizer renders: “French Scarlet 'twas, its Colour well it kept; / So smooth that Louse upon its Surface crept.” More often the translation is as faithful as possible given the different forms: “Put hem in a pressour & pynned hem þer Inne / Tyl ten зerde or twelve telled þrettene” (5.127–8; fol. 118r) becomes: “So well was stretch'd my Cloths, that e'en / Ten or twelve yards wou'd measure out Thirteen.” What survives of the modernization, printed in the Appendix to this chapter, is faithful, engaging, and entertaining. Its failure to be published was a substantial loss to readers of the nineteenth century and today (see Figure 15).

Figure 15 From Dupré’s modernization of Piers Plowman.

Aftermath: Margaret de Valois and the pilgrim of Douce 104

How was Dupré found out? And how did these specimens of Piers Plowman end up in Francis Douce's hands? These questions share an answer. Douce's fame as antiquarian collector of ancient manuscripts has made his acquisition of these three manuscripts seem perfectly standard, and wholly unconnected to the Monthly Magazine shenanigans. But with collecting came an unmatched knowledge of medieval European and British literature and history, one far deeper than that attained by most of the gentlemen who read that periodical. This was Dupré's undoing, as the inscriptions inside the back cover of MS 319 (Brunetto's Tresor) reveal: “Mr. Dupré presents his Compliments to Mr. Douse, and as he wished to possess the Manuscript of Brunetto Latini it is herewith left at his House at his Disposal. / No. 28, Poland Street. / Saturday, Oct. 1802.” This is followed by two more items, both in Douce's hand, inscribed at different times: “This was the person whose forgeries I detected in the Monthly Magazine,” in ink, and “See Monthly Mag. for 1802, p. 391,” in pencil. Now, we have already seen that of 323, the Middle English manuscript, Douce says “I purchased this Ms. of M. Dupré.” In the final of the three, MS 227, Douce writes, “I had this MS from M. Dupré who has given an extract from it in the Monthly Magazine for 1801, p. 36” (Douce seems confused: the extracts are in the May 1802 volume, pp. 355–9), adding a brief description together with further bibliographical information about the “Roules d'Oleron” from which Dupré had quoted.

Both scholars who have discussed the episode have assumed that Douce purchased MSS 227 and 319, as he had 323, from their previous owner.54 But the entries by these successive owners of 319 point to different means by which that manuscript changed hands and also thus of the probable circumstances of the two sales. The fact of Dupré's inscription itself is telling, for unless the person with the pen is a famous author at a book signing, one does not usually inscribe an item sold to another, and indeed neither of the other two is so marked. Something odd also lies behind the claim that Douce “wished to possess” this manuscript. The most probable reason behind this desire is that, as Douce points out, he was the one to detect the forgeries that were inspired by it, upon which he must have confronted their perpetrator and extracted the primary source of the deception from its owner as a payment of sorts to the society of men of letters and as his own reward. Afterwards Douce took pity on the man, and did indeed purchase the other two manuscripts. The fact that all three were being used for the forgeries in 1802 identifies July of that year as the terminus a quo of their transmission to Douce.

Most Langlandians probably know “Douce” as the name of a manuscript (104, the illustrated one, rather than 323), and not as a historical figure who played an important role in creating the Piers Plowman archive, but it is clear that that role extended well beyond the mere collection of manuscripts and printed editions to pass on to the Bodleian. Without him the only thing we would know about the first modernization of the poem would be what Wright says. And like the figures who populated Chapter 5, he left his mark on the manuscript. To facilitate cross-referencing among his two manuscripts and the editions of Crowley and Whitaker, he transcribes the opening line of each passus on the frontleaves. He also comments on a few variants in the opening lines, such as the “soft/set” crux, and mentions another otherwise unknown episode in the eighteenth-century reception of Piers Plowman: “There was a transcript (collated) of a part of P. Plowman made by one Frederick Page from MSS in the B. Museum about the year 1797. His papers lay a long time in the reading room. Q. what became of them & of Mr. Page himself who was known to my valuable & excellent friend Mr Brown the traveller” (fol. vir). This Frederick Page is probably the writer on the poor laws (1769–1834), drawn by the poem's treatment of the indigent.55 (“Mr Brown the traveller” remains a mystery.) Whoever Page was, a portion of his transcription, taken from MS Cotton Vespasian B xvi, survives, even if not in any Langland scholarship to date, still in the collections of the institution where Douce saw them, now as BL Additional MS 6399A, fols. 29r–31v.56

Dupré did not slink into obscurity upon Douce's unmasking of the faker. Just over a year after it confessed to having been duped by the translator, The Monthly Magazine published the announcement that Mr. Dupré, compiler of the Lexicographia-Neologica Gallica,

is preparing for the press a Translation of the Memoirs of Margaret de Valois, first wife of Henry the Fourth of France, written by herself, and containing the Secret History of the Court of France for seventeen years, from 1565 to 1582, including her Relation of the Massacre of the French Protestants in 1572, commonly styled the Massacre of St. Bartholomew's Day. These Memoirs will be illustrated with Historical Notes, drawn from Brantome and other writers, the whole forming a History of the Age and Times of Henry the Great, the wisest and best Monarch France ever knew.57

Claudio Giunta brought this notice to light, but could not find any trace of the promised book.58 In fact it would finally be published much later, in 1813, under almost exactly the title here indicated, but saying only: “Translated from the Original French, with a Preface and Geographical Notes, by the Translator.”59 Perhaps the delay and lack of attribution were the effects of the scandal of 1802. Whatever the case, this production is in keeping with the “Brunetto” letters, both in its epistolary form and in its purpose of illustrating “an Age.” The Monthly Magazine's revelation of the forgery reported that Dupré “only meant to give a picture of English literature and manners, as they existed in that period, in imitation of the French Anacharsis.” The modernization of Piers Plowman would have done the same, too, had it seen the light of day.

The authenticity of Margaret of Valois's letters is not in question, but even so the reviewer for The Monthly Review was cautious because “the French booksellers are very dextrous in manufacturing memoirs of persons of consequence.” But other than alerting its readers that “the memoirs relate less to the general politics of the kingdom than to personal anecdote, in which respect they will gratify those who wish to view the interior of courts,” the review finds everything perfectly acceptable.60 Thus does the Tory perpetrator of literary scandal find his way onto modern bibliographies in celebration of women writers.61

For students of Piers Plowman there is another, even more obscure and haunting trace of Dupré's career, of which he was surely ignorant and which could not have made any sense to anyone but Francis Douce himself until now. It is found in MS 104, which Douce had purchased at the sale of John Jackson on April 28, 1794, at least eight years before the Dupré manuscripts came into his possession.62 Yet the Dupré Piers Plowman had a material effect on the earlier, more famous acquisition, and in particular on what is certainly the most widely reproduced of its illustrations, that of the pilgrim on folio 33br.63 Shorn from context, the image seems perfectly suited to serving as a representation of the poem, which is about a dreamer's journey, as it were. But of course this is the fraudulent man, who says he has been to all the great shrines, but knows nothing of “St. Truth.”

It is worth keeping the pilgrim's character in mind when analyzing the slip of paper, now fol. 33a, that has been inserted between fol. 32 and 33b. On the recto, Douce transcribes the twelve-line poem, “Tutiuillus þe devyl of hell,” that appears on fol. 112v, but on the verso is pasted a scrap of paper with two jottings for Douce's personal use, which are very difficult to decipher. The item in pencil, on the right, appears to read: “Pilgrim collate will / Both MSS & add / to the Pilgrims story,” though any rendering must be provisional: the prominence of a “Will” and of the “collar” of the drawing suggests some alternatives. Perhaps Douce is telling himself that he wants to collate this passage with the equivalent in his newer copy, MS 323. Yet the passage is very similar in the two texts so it is unclear why he would pick it as object of collation. The other item, in ink, seems to read: “See Illum? MS p. 33 / Ms Duprè fr. / where paper”: Douce here tells himself to go to the illumination on p. 33, that of the pilgrim, where he has added the slip of paper; my best guess as to what I see as “fr.” is that it is an abbreviation for “Frenchman” (see Figure 16).

In any case something about the portrait of the fraudulent pilgrim seemed different to Douce in light of his acquisition of the Dupré MS. The most obvious, if not secure, conclusion is that he saw in this image a representation of Dupré himself. Fraudulence is not the only thing that unites the two, though: so does a sense of poignancy, even dignity. The paperbacks that sport the image are not promoting Piers Plowman's satirical impulses; they are invoking its association with the simple, poor seeker. Likewise Douce allowed his relationship with the forger to reach more equitable grounds than it had when he strong-armed MS 323 away from Dupré: hence his purchase from him of two manuscripts, including the one containing Piers Plowman. There must have been something worth either pitying or respecting – more likely the latter, given what we now know of his substantial contributions to the world of letters – in this man. Whatever it was, there is no question that Douce was thinking of this forger, this first modernizer of Piers Plowman, when he turned back to his other copy. He could not get Dupré out of his mind.

Appendix: William Dupré's modernization of Piers Plowman

Dupré's modernization is quite polished and not in any need of emendation, punctuation, or the like. I have changed his underlining to italics, and omitted the catchwords at the bottom of each page. The first passage renders A 5.107–45, Covetousness's confession, from fol. 118r–v of the manuscript; the second, Hunger's advice to Piers at A 7.237–61, from fols. 125v–126r. At the bottom of iiv is Douce's comment “The above specimen by Mr. Dupré of whom I purchased this MS. F.D.”

Passus Septimus – Yet I pray thee quoth Piers &c:

* Our Lady of Walsingham, & Bromeholme Priory; both Places of great Sanctity in Norfolk.