Introduction

Though frequently dismissed as “just a bit of fun” (Way Reference Way2021, 489), popular culture’s role in influencing and reflecting broader political developments is finally starting to receive the academic attention it deserves. After all, it is through popular cultural mediums including art, sport and music, that people most often experience and consume politics as part of the “taken for granted everyday world” (Machin Reference Machin2013, 347). Yet, it is precisely this inseparability from the ideologies and power relations with which they are infused (Machin, Reference Machin2013, 347) that make popular cultural forms such a rich subject for academic research into expressions of non-hegemonic identities.

Whilst acknowledging the importance of prior studies, which examine state-centered initiatives and policies aimed at facilitating Estonian nation building and integration, such approaches cannot paint a full picture of identity formation processes in Estonia alone (Polese et al. Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Pawłusz and Morris2018, 1). This appears particularly true when considering the non-hegemonic Russophone Estonian identity, the lived experience of which rarely aligns with narratives produced and disseminated on a state level. Therefore, this article approaches the issue of Russophone Estonian identity from the oft-neglected perspective of its expression through popular culture, with a specific focus on a hit hip-hop song and its accompanying video. Doing so, not only complements the aforementioned top-down examinations of identity in Estonia, but also underlines that, despite being frequently overlooked in academic studies, products of popular culture created by members of minority communities provide rich material, from which nuanced insights into “dynamics contributing to identity construction” in day-to-day lived experiences can be drawn (Polese et al. Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Pawłusz and Morris2018, 1, 3).

Popular music for instance, more than simply a form of creative expression, is increasingly seen as reflecting and affecting definitions of culture and identity in societies (Machin Reference Machin2010, 2). For musicians and their audiences, music is a medium through which “meaningful worlds in which to live” are constructed (Machin Reference Machin2010, 2). For young people especially, music plays an important role in the formation and presentation of social and political attitudes (Piroth Reference Piroth2008, 146). As a sphere where aspects of majority and minority identities are often performed to a higher degree of intensity than in other areas of everyday life, popular music is therefore a valuable and under-examined platform through which to explore identity expressions (Pawłusz Reference Pawłusz, Polese, Morris, Pawłusz and Seliverstova2020, 36).

One popular music genre where this seems most apparent is hip-hop, the successful marketing of which, in a range of national contexts, involves presenting artists from minority groups as “authentic” (Bower Reference Bower2011, 380). Since its emergence in the early 1990s, Estonian hip-hop has developed in line with many other cultural and artistic projects in the country, inherently reflecting socio-cultural attempts to foster a seemingly homogeneous society, yet ultimately cultivating one where diversity and multiculturalism continue to prevail (Vallaste Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 129). Several Estonian hip-hop musicians have, both lyrically and visually, explored aspects of being “post-Soviet” in contradistinction to official hegemonic discourses (Pasdzierny Reference Pasdzierny2018, 29), which outright reject the Soviet past (Smith Reference Smith2008, 421) and emphasize titular ethnicity as a cornerstone of national identity (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 305).

Taking the popular hip-hop song “für Oksana” by Nublu featuring Gameboy Tetris as a case study, this article adds nuance to understandings of Russophone Estonian identity. Combining a Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of the song’s lyrics with a Multi-Modal Discourse Analysis (MMDA) of the settings, symbols, and characters in the accompanying music video, demonstrates several unique discursive characteristics, which are neither “fully” Russian, nor Estonian. I argue that through a combination of linguistic and cultural codeswitching, “für Oksana” constitutes an expression, performance, and negotiation of Russophone Estonian identity, from both insider and outsider perspectives, emphasizing the need to understand Russophone Estonians as more than simply “Russians who live in Estonia.”

Russian-Speaking Minorities in Estonia

After decades of social and economic policies designed to reconstruct Estonia as an integral component of the Soviet Union (Mettam and Williams Reference Mettam and Williams2001, as cited in Vetik and Helemäe Reference Vetik and Helemäe2011, 14), when the country regained independence in 1991, almost a third of the population were ethnic Russians (Statistical Office of Estonia 1995). These demographic changes, which saw a dramatic reduction in the proportion of ethnic Estonians living in Estonia between 1945 and the Soviet Union’s collapse, also caused huge increases in Russian language use at the expense of Estonian (Smith Reference Smith2013, xxiii; Trapans Reference Trapans1991, 77). To redress the perceived imbalance in ethnic composition, the newly empowered Estonian political elites sought to establish a modern state based on the legal continuity principal (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 305), emphasizing Estonian ethnicity as the foundation of national identity (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka, Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 305), and rejecting all traces of the Soviet period (Smith Reference Smith2008, 421). As a result, in 1991, practically overnight, almost 500,000 Russians who found themselves living in a newly re-independent Estonia were considered “aliens” and no longer automatically granted citizenship (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 291). While many chose to relocate to Russia during the 1990s (Kallas Reference Kallas2016, 15), those who stayed were required either to pass Estonian language and civics exams to become citizens (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 305), or remain “stateless,” an option many preferred (Astapova Reference Astapova2021, 1).

Members of Estonia’s Russian-speaking population have often struggled to fully integrate with the titular majority, maintaining closer linguistic, cultural, and historical ties to Russia than Estonia (Kallas Reference Kallas2016, 15) and prolonging the existence of what at times appears to be two parallel societies living alongside each other but divided along ethnic lines (Lindeman and Saar Reference Lindemann, Saar, Vetik and Helemäe2011, 84). On a political level, one reason these divisions continue to prevail (Lindeman and Saar Reference Lindemann, Saar, Vetik and Helemäe2011, 84) are perceptions amongst the Estonian elite of Russophones’ potential for disloyalty to the state (Agarin Reference Agarin2013, 343). According to Agarin (Reference Agarin2013, 331, 343), such attitudes mean Russian-speaking elites in Estonia are often discouraged from participating in political decision-making, fostering a sense of disaffection with political systems and leading to low levels of political participation amongst Russophone Estonians in general (Cianetti and Nakai Reference Cianetti and Nakai2017, 284). This political indifference may partly result from Russian-speakers generally occupying lower socioeconomic status than ethnic Estonians, but may also be because, having arrived in Estonia during separate “waves of immigration” during the Soviet period, they lack an inherently homogeneous sense of identity (Cianetti and Nakai Reference Cianetti and Nakai2017, 284).

Yet, somewhat ironically, perceptions of being outside, or peripheral to, the society may have inadvertently created a relatively stable form of collective Russophone Estonian identity, though, admittedly, one which “remains fairly fragmented” (Cheskin Reference Cheskin2015, 78, 87). Mirroring attitudes in the other two Baltic states, the tendency in Estonia for Russian-speakers to believe titular elites discriminate against their interests and culture (Cheskin Reference Cheskin2015, 81) highlights another major factor in the prolonged existence of a seemingly divided society; mutually reciprocated feelings of cultural threat (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 289; Vetik and Helemäe Reference Vetik and Helemäe2011, 16). Estonia is fairly “atypical” in this sense, as ethnic Estonians assume the position of a “threatened majority” in their own country (Vetik and Helemäe Reference Vetik and Helemäe2011, 18–19), constantly wary of the potential for Russia in particular to once again impose itself culturally and politically. In contrast, as a residual hangover of the Soviet past, Estonia’s ethnic Russian population occupies the role of a “formerly privileged” minority (Vetik and Helemäe Reference Vetik and Helemäe2011, 15), symbolically embodying this notion of threat to the titular culture and language.

Because these two “parallel” societies continue to interact with each other minimally in both structural and cultural domains (Vetik and Helemäe Reference Vetik and Helemäe2011, 15), naturalization of the Russian-speaking population is a long-standing goal of Estonian integration programs to “overcome social cohesion problems and promote identification with the country of residence” (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 305). However, Estonian integration policies have not only emphasized the need for Russian-speaking minorities to achieve a degree of proficiency in the Estonian language (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 299), but also to adopt aspects of the titular identity, which assume sets of preconceived Estonian cultural values (Nimmerfeldt Reference Nimmerfeldt, Vetik and Helemäe2011, 190). As a result, feelings amongst Russian-speakers that such policies are attempts at “forced assimilation” rather than mutual cultural integration are not entirely unjustified (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 299). However, despite fears this may lay the ground for potential ethnic conflict (Vetik Reference Vetik and Vetik2007), Estonia’s Russian-speaking population tend to express positive attitudes toward living in the country (Polese, Seliverstova et al. Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Kerikmae and Cheskin2020, 1027). One significant clash did occur in April 2007 during the so-called “Bronze Soldier” riots, when over a thousand young Russian-speakers were arrested following violent protests against the removal of a Soviet Second World War Monument from Tallinn city center (Ehala Reference Ehala2009; Cheskin Reference Cheskin2015, 79). Yet, such incidents are extremely rare, with the general positivity Russian-speakers feel toward Estonia often explained as resulting from the social and healthcare benefits available to them, as well as employment and travel opportunities, which visibly outweigh those on offer should they relocate to Russia (Polese, Seliverstova et al. Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Kerikmae and Cheskin2020, 1027). Thus, even though Russian-speakers are more likely to belong to lower socio-economic groups or be unemployed than ethnic Estonians (Heidmets Reference Heidmets2008, 53), their access to these benefits and services contributes to redressing the imbalance (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 299).

Pfoser (Reference Pfoser2017) additionally highlights local discourses among residents in Estonian border town Narva and its Russian neighbor Ivangorod, in which the economic and social benefits in Estonia are understood as part of the notion of being “European,” an identity marker used to positively differentiate Russophone Estonians from those living across the border. This may partly result from top-down Estonian discourses of “returning to Europe,” which were a major component of the country’s re-independence narrative, aimed at emphasizing the illegality of Soviet rule, yet also acting as a mechanism to effectively “other” Russian minorities in the country (Jordan Reference Jordan2014, 21). Regardless, this highlights self-perceptions among Russophone Estonians of their difference from Russians in Russia (Cheskin Reference Cheskin2015, 81). According to Pfoser (Reference Pfoser2017, 41), such understandings appear reciprocal, as Russians in Ivangorod also tend to see Europe as entirely distinct from Russia, and therefore, incompatible with their own, unique “non-European” identity.

Despite Russia’s enduring cultural attractiveness (Cheskin Reference Cheskin2015, 73) and accessibility, it is important not to assume that for second and third-generation Russophone Estonians, choices between Russia and Estonia are as tangible or binary as they perhaps were for their parents and grandparents. Availability of online governmental services, higher quality healthcare, and EU membership are clearly important in fostering attachment to the Estonian state (Polese, Seliverstova et al. Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Kerikmae and Cheskin2020, 1027), however, having never lived in Russia, many young Russophones also feel emotionally connected to Estonia, considering it their only homeland (Kallas Reference Kallas2016, 12). For this reason, Vetik and Helemäe (Reference Vetik and Helemäe2011, 18–19) categorize younger generations of Russophones as “semi-immigrants” in Estonia, integral to the society in certain respects, yet external and peripheral in others. Thus, where the aforementioned binary understandings of Russian and Estonian identities continue to shape decisions at a political level, on a day-to-day basis amongst Russophone Estonians, ambiguous and fluid senses of “hybrid identity” and belonging appear more common (Polese, Seliverstova et al. Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Kerikmae and Cheskin2020, 1029).

The emergence of this hybridity seemingly supports notions that Russophone Estonians’ self-conceptions of identity occupy a space “in-between” two cultures, which, for several historical and geopolitical reasons, are frequently portrayed as incompatible. Yet it also challenges implicit assumptions that Russian and Estonian identities are mutually exclusive. Such ambiguity suggests the need to examine how concepts of cultural and territorial identity have evolved, creating a new sense of identity that perhaps metaphorically faces both Russia and Estonia – and also neither at the same time – in a fluid form of uniquely “Russophone Estonian” hybridity. To do so, this article analyzes the representation, performance, and negotiation of Russophone Estonian identity in a popular hip-hop song and music video set in Narva, an Estonian border city with a majority Russian speaking population (Muiznieks, Rozenvalds, and Birka Reference Muiznieks, Rozenvalds and Birka2013, 291).

Since 2004, Narva has not only marked the point where Estonia ends and Russia begins, but also the eastern edge of the European Union, a boundary which in Estonian discourses is often framed as a “deep-seated civilizational divide” (Pfoser Reference Pfoser2017, 27). Located “literally and symbolically at the margins” (Pfoser Reference Pfoser2014, 272), Narva is often considered peripheral to the hegemonic Estonian center, and its residents, known as “Narvians,”Footnote 1 internally “othered” (Martínez Reference Martínez2020, 68), due to their enduring linguistic and cultural ties to Russia. Precisely for these reasons, Narva found itself central to broader geopolitical narratives (Martínez Reference Martínez2020, 85) following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. The city became the focus of international speculation from journalists and analysts alike, amid fears Vladimir Putin could invade Estonia under the guise of offering “protection” (Kasekamp Reference Kasekamp2015, 30) to Narva’s 95% Russian-speaking population (Pfoser Reference Pfoser2014, 272). After all, speaking Russian as a first – and usually only – language means Russophone Estonians exist in a largely separate information space to the rest of Estonia’s population, with many noted to be in favor of the Crimean annexation (Kasekamp Reference Kasekamp2015, 31).

However, as Kallas (Reference Kallas2016, 14) and Kasekamp (Reference Kasekamp2015, 31) state, for no one are contrasts between Russia and Estonia more visible than Narvians, who have ample opportunities to compare life in the two countries during regular crossings to the Russian city of Ivangorod, which stands facing Estonia across the Narva River. That Narvians prefer to remain in Estonia is thought to result predominantly from the aforementioned pragmatic reasons overriding linguistic, cultural, or even emotional factors, connecting them more closely to Russia (Polese, Seliverstova et al. Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Kerikmae and Cheskin2020, 1027). However, among Russophone Estonians, there is also a growing sense of attachment to Estonia beyond purely pragmatism, and this is no less true for Narva residents. For Narvians, not only is Narva Estonia and not Russia, but conceptualizations of Estonia also stem from experiences firmly rooted in Narva itself.

While official discourses provide awareness of top-down understandings of identity issues, bottom-up approaches offer valuable insights into their realization on a day-to-day basis (Polese, Morris et al. Reference Polese, Morris, Pawłusz and Seliverstova2020, 2). One useful tool for examining the contradictions inherent in considering Russian and Estonian identities in purely binary terms are cultural items produced by Russophone Estonians themselves, which explore personal experiences of both “being Russian but loving Estonia” (Lyapin Reference Lyapin2018). Doing so enables deeper understanding of why issues presented in such works resonate with a community, which though not fully able to embrace cultural tropes in either Russia or the rest of Estonia, is attached to a unique combination of the two, that for them is neither contradictory nor inconsistent. To highlight the benefits of music and music videos in analyzing these issues, the next section outlines the relationship between popular music and expressions of identity.

Popular Music and Identity

For Piroth (Reference Piroth2008, 146), “popular songs tell stories about social groups, stories that form part of a narrative that helps individuals find their place in the world and develop a political identity.” This storytelling most frequently occurs in song lyrics, which, when subjected to critical analysis can reveal “deeper meanings that tie them to particular times, places and ideas” (Machin Reference Machin2010, 2). It is in song lyrics, where musicians may choose to combine linguistic practices associated with different social groups, and incorporate specific dialects or slang words, to indicate and perform aspects of majority or minority identities (Brusila Reference Brusila, Helms and Phleps2016, 12).

Exemplifying this, and one of many instances when identity politics featured in the Eurovision Song Contest, was the performance of Ukraine’s 2007 contestant “Virka Serduchka.” Serduchka’s use of the hybrid Russian-Ukrainian language surzhyk contrasted with official state efforts toward constructing a form of national identity bound to the titular Ukrainian language, and instead reflected the post-Soviet reality of everyday language use in Ukraine (Pavlyshyn Reference Pavlyshyn, Kalman, Wellings and Jacotine2019, 135). Yet, as Brusila (Reference Brusila, Helms and Phleps2016, 9) states, it is not only the words in song lyrics that indicate performers’ “ethnic, social or aesthetic positions.” Decisions to use specific phrases, codeswitching between languages, pronunciation style, and inclusion of dialect, in addition to commonly employed linguistic tools including humor, irony, and even ambiguity (Brusila Reference Brusila, Karjalainen and Kärki2020, 93), combine to create unique identity expressions (Brusila Reference Brusila, Helms and Phleps2016, 9). Beal (Reference Beal2009, 238) for instance, highlights Arctic Monkeys’ use of the local Sheffield accent and dialect, both to reject “American” style pronunciation typical of pop music singing, and simultaneously assert their northern Englishness.

One genre of popular music where expressions of identity appear most common is hip-hop, the successful marketing of which in a range of national contexts involves presenting artists from minority groups as “authentic” (Bower Reference Bower2011, 380). Hip-hop performers, who purport to portray the true state of society, “warts and all” (George Reference George, Biddle and Knights2016, 101), through their music, express themselves “both artistically and socially” (Brusila Reference Brusila, Karjalainen and Kärki2020, 93), by drawing on existing repertoires of local vernacular culture (Machin Reference Machin2010, 4; Beal, Reference Beal2009, 231). As Brusila (Reference Brusila, Karjalainen and Kärki2020, 89) notes, hip-hop artists codeswitch between official and vernacular languages, dialect and slang, perhaps more than producers of any other genre of music, contributing to the formation and reformulation of ethnic identities. This mixing of languages is one way in which feelings of being outsiders to hegemonic cultures may be expressed (Brusila Reference Brusila, Karjalainen and Kärki2020, 89), with hip-hop often used as a platform to contest understandings of nationality and hybrid identities (Mitchell Reference Mitchell2001, 32; George Reference George, Biddle and Knights2016, 104). George’s (Reference George, Biddle and Knights2016, 111) study in the French context for instance, highlights hip-hop and rap’s roles as identity markers in opposition to mainstream French cultural norms, embraced by those seeking to challenge centrally imposed linguistic and cultural hegemonies and instead increase recognition of France’s linguistic diversity (George Reference George, Biddle and Knights2016, 93).

Connected to this is hip-hop and rap artists’ continued identification “with particular regions, cities and neighborhoods” (Signer and Balaji Reference Sigler and Balaji2013, 336), which are often referenced in song lyrics and shown in accompanying videos (Rose Reference Rose1994, 10). In the US context from which hip-hop originates, this generally amounts to glorification of economically deprived areas, with the more vivid the description presented, the more audiences perceive artists as “real” (Peterson Reference Peterson2005; Signer and Balaji Reference Sigler and Balaji2013, 342). However, as hip-hop has become increasingly visible in mainstream US popular culture, it has also found new localities and global audiences, along with musicians in different countries producing localized variations on the original themes (Tervo Reference Tervo2014, 175). In Brazil, São Paulo hip-hop artists incorporate frequent mentions of local landmarks of transit and nightlife in their lyrics, and use first person pronouns to place themselves as subjects of, what Pardue (Reference Pardue2011, 105) terms, “imaginative geographies,” creating the impression of collectivity. Likewise, French rappers from immigrant backgrounds often reference provincial towns in France, or Parisian suburbs, asserting their belonging to particular communities, though not always for positive reasons (George Reference George, Biddle and Knights2016, 97). The next section turns to hip-hop’s growth in Estonia, highlighting its relationship with developments in the country’s political culture since independence.

Hip-hop and Sociopolitical Developments in Estonia

Estonian-language hip-hop first emerged in the early 1990s, after Estonia regained independence from the Soviet Union (Vallaste Reference Vallaste2018, 63). Accessible from the outset to “virtually anyone who had something to say and owned a computer” (Vallaste Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 129), hip-hop has since become one of the most popular genres of locally produced music in Estonia. The limited scope of, and potential markets for, Estonian-language music created space for an eclectic range of performers to produce hip-hop on a wide variety of topics from “competitive binge drinking” to “making pancakes with grandmother” (Vallaste Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 130). Though Vallaste (Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 130) states no strong lyrical, or even stylistic themes adequately encapsulate the diverse array of Estonian hip-hop artists, this apparently disparate constellation of styles and lyrical themes inadvertently appears to reveal a lot about “both the legacies of Soviet rule and the particular political economy of post-Soviet Estonia” (Vallaste Reference Vallaste2018, 63). After all, hip-hop’s growth in popularity parallels Estonia’s re-emergence into the international community, first as an independent nation, and second as a European Union member state. Thus, like many other cultural and artistic projects in Estonia, hip-hop inherently reflects the country’s socio-political developments during this period, exemplified by three major trends (Vallaste Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 132).

First, antiauthoritarian lyrics in the early works of Estonian hip-hop pioneers including “A- Rühm” demonstrate the process through which global forms of musical resistance became localized to Estonia (Vallaste Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 132). Second, is Estonian hip-hop artists’ skillful utilization of new forms of technology to create music, both mirroring and resulting from, top-down initiatives, including the “Tiger Leap” program, which pushed Estonia towards becoming an advanced digital society (Vallaste Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 132; Sai and Boadi Reference Sai and Boadi2017, 9). Third, and most salient for this study, are negotiations between the perceived need to establish a homogenous Estonian society, and acceptance of seemingly incompatible EU values regarding preservation of difference and multiculturalism within nation states (Vallaste Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 129; Pfoser Reference Pfoser2014, 269). As Estonia’s potential EU membership became central to public discussion during the late 1990s and early 2000s, several Estonian hip-hop artists adopted “ultrapatriotic and conservative stances” in resistance, including previously cosmopolitan and progressive A-Rühm, whose song “Nations Are Dead” was later used by ultra-nationalist politician Margus Õunapuu during an election campaign (Vallaste Reference Vallaste, Miszczynski and Helbig2017, 137–8).

Contrasting with A- Rühm’s forays into xenophobia and nationalism, the early 90s Estonian hip-hop scene mixed both Russian and Estonian native speaking contributors, in a sense providing an organic platform for cultural integration outside mainstream frameworks (Kagovere Reference Kagovere and Martínez2015, 82). Yet, where Estonian-speaking performers of that period tended to rely on clichéd local re-imaginings of music from the US, the Russian-speaking community “had real problems,” inspiring an increased sense of outsider authenticity in their music (Kagovere Reference Kagovere and Martínez2015, 81). Estonian-produced hip-hop clearly lacks the racialized antagonisms inherent to music of artists from minority communities in other European countries, such as those discussed by Rollefson (Reference Rollefson2021, 2). However, in the Estonian context, the assertion of “post-Sovietness” in contradistinction to the hegemonic understanding of national identity, may function in a similar way (Pasdzierny Reference Pasdzierny2018, 35), by giving “voice to the ideal of equality through anti-assimilationist expressions of minority difference” (Rollefson Reference Rollefson2021, 2). Not least because, as Cheskin (Reference Cheskin2015, 88) notes, in Estonia, public portrayal and performance of Russian identity may be considered political in and of itself.

Thus, while performances of identity tend to be more intense in music than other spheres of everyday life (Pawłusz Reference Pawłusz, Polese, Morris, Pawłusz and Seliverstova2020, 36), explorations of these issues by Russophone Estonian hip-hop artists offer a useful basis to examine self-conceptions of identity from within the community. One example is Narva-born rapper Yevgeniy Lyapin’s (also known as “Stuf”) song “Olen Venelane” (“I am Russian”), containing lyrics critical of those “blaming everyone, including the Riigikogu” (Estonian Parliament) for low salaries and high taxes,” and who “dream of a distant kingdom” (Lyapin Reference Lyapin2018), ostensibly Russia. Lyapin claims the lyrics do not address anyone in particular (Tooman Reference Tooman2017), however, these sentiments, and the line “I am Russian but love Estonia,” suggest feelings of frustration toward Russophone Estonians who, despite choosing to live in Estonia, continually complain about it (Tooman Reference Tooman2017; Makarychev Reference Makarychev2021, 68). The video accompanying “Olen Venelane,” filmed in Narva, features Stuf wearing blue, black, and white clothing, apparently signifying the Estonian flag, and concludes with the rapper facing across the Narva River toward the Russian town Ivangorod.

While Stuf’s level of fame remains rather modest and local to Estonia, singer and artist Tommy Cash, who was born in Tallinn’s Kopli district, has gained international acclaim by proudly flaunting a Russian “gopnik” style, signifying both his “Easternness” and “post-Sovietness” (Pasdzierny Reference Pasdzierny2018, 29). Comparable to British “Chavs” or “Neds” (Young Reference Young2012; Jones Reference Jones2020, or “white trash” in the US, “gopniki” are stereotypically portrayed as wearing tracksuits (usually Adidas) and flashy jewelry, and performing a specific type of macho persona (Engström Reference Engström and Semenenko2021, 98) including drinking vodka, smoking cigarettes, and “squatting” (Klee Reference Klee2018; Raspopina Reference Raspopina2016). Despite the term’s derogatory origins, the popularity of “Slav” memes has also elicited a sense of pride amongst some, who celebrate the gopnik as an ironic countercultural persona (Klee Reference Klee2018). In adopting this persona, Cash combines parody, surrealism, and the grotesque, celebrating an identity commonly considered inferior to the popular Western cultural tropes, which many other Estonian hip-hop artists simply tend to mimic with little desire to add local twists (Pasdzierny, Reference Pasdzierny2018, 32). Cash’s work in particular demonstrates that not only lyrics, but also videos, artwork, and live performances provide Russophone Estonian hip-hop musicians space to perform and negotiate facets of identity.

Examining both these performers’ works in detail would certainly reveal additional nuances relevant to understanding expressions of Russophone Estonian identity, however, doing so is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, the lyrics and video of popular 2019 hip-hop song “für Oksana” by Nublu featuring Gameboy Tetris were chosen for deeper analysis, for four main reasons. First, the main theme of the song and video is the unique experience of life in the majority Russian-speaking Estonian city of Narva. Although neither of the song’s performers, Nublu and Gameboy Tetris, nor the video’s director Marta Vaarik, are Narvians, the ideas presented indicate connections to, and awareness of unique local discourses. Second, “für Oksana” combines linguistic and visual methods of expressing these local identity discourses. While analyzing music videos creates additional challenges for researchers (Tervo Reference Tervo2014, 172), the combination of visual manifestations of the performance of local identity in Narva, alongside linguistic articulations, adds an additional dimension, which has thus far been underexplored in the literature.

Third, “für Oksana” was generally received positively by Narvians and in Estonia more broadly, where it is especially well known for the Russian language lyric “Привет город Нарва” (“Privet Gorod Narva” – “Hi Narva town”). Such is the popularity of “für Oksana” that throughout September 2020, the song’s tune was played by the iconic clock in the Town Hall Square of Estonia’s second largest city, and center of Estonian culture, Tartu, to “catch the attention of young people” (Tooman Reference Tooman2020). Earlier the same year, it became the subject of a parody video called “für Vene Teatri Sõber” (For a Friend of the Russian Theater), produced by a collective affiliated with the Tallinn’s Russian Theatre in Estonia (Malova Reference Malova2020). Thus, while themes presented in the lyrics and video may not be representative of every individual’s experience of being Russophone Estonian, the unique elements of life in Narva, and the city’s figurative location within Estonia discourses, which “für Oksana” captures, clearly resonated with large numbers of Russophone and ethnic Estonians alike.

Finally, while Narva is commonly understood as a purely Russophone city, “für Oksana” demonstrates degrees of hybridity in its articulation and performance of local identity. Codeswitching between Russian and Estonian languages as well as linguistic and visual references to cultural tropes from both Russia and Estonia, alongside mentions of uniquely local spaces and issues, suggests potential for more nuanced understandings of the fluid – rather than binary – features of “Narvian” and, by extension, “Russophone Estonian” identity (Makarychev Reference Makarychev2021, 68). However, as Makarychev (Reference Makarychev2021, 68) highlights, unlike “Olen Venelane” by “Stuf,” Nublu and Gameboy Tetris play with both insider and outsider understandings and perceptions of Russophone Estonian identities, exoticizing and possibly further contributing to the orientalization of Narvians in the eyes of ethnic Estonians. The next section outlines the methodological approaches used to explore these issues.

Methods

The initial stage of analysis involves identifying the song’s discourse schema, or basic narrative progression, to reveal the underlying social values presented (Machin Reference Machin2010, 78). The lyrics of “für Oksana” are then examined using Fairclough’s (Reference Fairclough1992) three-step framework for Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA). The first step identifies linguistic features of texts, focusing on representations of social actors, agency, and evaluative terms used to assess actions or events (Fairclough Reference Fairclough1992). The second level evaluates discourses as products distributed for societal consumption, and the third assesses discourses as forms of social practice, reflecting existing power structures in societies (Fairclough Reference Fairclough1992).

Multi-modal discourse analysis (MMDA) is then used to examine the song’s accompanying video. MMDA understands “texts” in a broader sense than simply language used, additionally including gestures, speech, images, writing or music (Kress Reference Kress, Gee and Handford2013, 36). MMDA aims to “provide insight into the relation of the meanings of a community and its semiotic manifestations” in texts, with an awareness that each “mode” has different sets of tools to facilitate expressions (Kress Reference Kress, Gee and Handford2013, 36). The analysis follows Ledin and Machin’s (Reference Ledin and Machin2018) framework, which considers visual discourses in videos according to settings (locations), symbols, and characters portrayed. These three overarching themes provide a basis to assess the expression, performance, and negotiation of Russophone Estonian identity in the video for “für Oksana.”

Analysis

Lyrics

Removing the narrative details of a song’s lyrics leaves only the basic structure, or discourse schema, which also reveals the underlying cultural values presented (Machin Reference Machin2010, 80). On a basic level, the discourse schema of ‘für Oksana”s lyrics is “A young Estonian man visits the Russophone city of Narva in search of a local girl named Oksana” (Makarychev Reference Makarychev2021, 68). This immediately reveals the presence of two opposing identities personified by the song’s lead characters. First, and most relevant to the current study, is the binary of ethnic Estonian (Nublu) and ethnic Russian (Oksana), with the male versus female distinction adding additional dynamics to these performed identities. Such binaries may be interpreted as simplified ways of presenting and negotiating more complex social issues or antagonisms existing in society (Way Reference Way2016, 8). Thus, Nublu’s character seems to embody hegemonic Estonian identity, and its metaphorical coming into contact with Oksana’s Russophone Estonian identity in Narva.

Closer analysis of the social actors represented, ways agency is attributed, and how actions or events are assessed in the song’s lyrics provides deeper insights into this basic underlying schema’s realization (Way Reference Way2016, 8; Fairclough Reference Fairclough1992). In “für Oksana,” the two most frequent actors are “I” / “me” / “my,” and “You” / “Your,” where the former represent the Estonian man (Nublu) and the latter, the Russophone Estonian girl (Oksana). Neither main character is referenced by name, though it is assumed from the song’s title that the girl is called Oksana, a fact supported by the opening sequence of the accompanying video (analyzed in more detail below), where Nublu tells a taxi driver “Let’s find Oksana” (Nublu 2019). As the song is narrated entirely from the perspective of Nublu (and co-performer Gameboy Tetris), Oksana never “speaks” directly in the lyrics. Instead, Oksana is described in the chorus as “my little Russian girl” (“mu väike venelanna”), and thus presented as a rather generic “type,” void of individual personality (Machin Reference Machin2010, 85). This one-dimensional portrayal is, however, somewhat counterbalanced by the deliberately more complex version of Oksana in the accompanying video (Mõttus Reference Mõttus2019).

Consistent with the discourse schema, Nublu performs more actions in the lyrics than Oksana, demonstrating a higher degree of agency. Nublu’s actions are both material (“I’ll fly to you,” “I can guard you at night”) and mental (“I already saw it coming”), whereas Oksana’s are mental (“you would like”) and relational (“you shine like a peacock and attack like an eagle”) and all presented from Nublu’s perspective. In the latter two examples, Nublu compares Oksana to birds, which may symbolize Christianity (peacock), and Russia (eagle), apparently in exotic contradistinction to Nublu’s hegemonic Estonian identity. Also frequent in the lyrics are actions Nublu and Oksana perform together, denoted by the pronouns “We,” “Us,” “Our,” and “You and I.” These include “let’s drink whiskey,” “we’ll speak English,” “let’s try again,” “we are together,” “we love money,” and “we have integrated.” When combined, these actions form a narrative, which, on the surface, simply appears to report the trials and tribulations of Nublu and Oksana’s personal romantic relationship. However, understanding Nublu’s role in the song as a representative of ethnic Estonians and Oksana as a Russophone from Narva, additionally suggests a commentary on negotiations of similarities and differences between these two communities, paralleling broader integration processes and experiences in Estonia since independence.

The second level of Fairclough’s (Reference Fairclough1992) approach to CDA considers discourses as products distributed for societal consumption. Numerous intertextual references (Spicer Reference Spicer2009) in the lyrics of “für Oksana” to predominantly Russian, but also Estonian, popular culture, suggest a conscious effort to appeal to listeners with prior knowledge of these cultural tropes and potentially invoke an “iconic effect” by association (Machin Reference Machin2010, 88). The 2004 Russian fantasy thriller movie “Ночной Дозор” (“Night Watch”) is mentioned, as Nublu vows to guard Oksana at night (“Sind valvata võin öösiti”). Nublu later compares his ability to predict the future to that of famous Russian psychic Alexander Sheps (“Ma nägin seda ette nagu Aleksandr Šeps”). The opening sequence of the video (analyzed in further detail below), also contains a reference to classic Russian coming of age film “Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears” (“Москва Слезам не Верит”), when Nublu’s taxi driver says, “Нарва слезам не верит” (“Narva does not believe in tears”). This line, included at the suggestion of director Marta Vaarik (Ida Repost 2019), may indicate an awareness of such well-known Russian cultural tropes amongst ethnic Estonians more broadly, particularly those in cities with large Russian-speaking populations.

“für Oksana” also includes intertextual references to Estonian culture and experiences, notably in the song’s name, which is a play on the title of renowned Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s piano piece “Für Alina” (Korsten 2019). Additionally, lyrics referring to both the time spent travelling to Narva – “kolm tundi veel” (“three hours more”) – and point of departure – “Siis kui Balti jaamast välja läheb rong” (“When the train departs from the Balti Jaam”) – would be clearly understood by listeners as references to a journey from Estonian capital Tallinn.Footnote 2 However, the inclusion of numerous references to local “Narvian” places, people, and symbols mark the song as more than a one-sided orientalization of Russophone identities and lives from an ethnic Estonian perspective. For instance, Nublu suggests Oksana meet him at Kreenholm (“Saame kokku seal kus Kreenholm”), a former textile factory, which was Narva’s main employer during the Soviet period, but is currently in a state of disrepair (discussed in further detail below). He also mentions well-known local bars “RoRo” and “Moderna,” where he offers to pay the bill (“И все же за мой счет всему RoRo, всему Модерну”), and Paul Keres, a chess Grandmaster born in Narva, commemorated in the city with a statue on the central Puškin Street and an avenue in his name.

In terms of symbols, the lyrics mention the orange and black St. George’s ribbon, “permanently intertwined” in Oksana’s hair (“Ma tean see Georgi lint su juuste sisse jäädavalt on põimunud”). Traditionally worn by Russians on May 9th to commemorate the Soviet World War Two “Victory Day,” the ribbon has become a symbol of “belonging, effective in performing an act of social linking” for Russian-speakers in and outside Russia (Oushakine Reference Oushakine, Buckler, Cassiday and Wolfson2018 in Martínez, Reference Martínez2020, 77). Wearing the ribbon in Estonia may be considered a visual performance of belonging to the Russophone community, which rather than following hegemonic Estonian state-promoted discourses, understands narratives surrounding the Second World War more in line with those in Russia. Curiously, the lyric about the St. George’s ribbon is juxtaposed with “Ja sina, mina lõimunud” (“You and I are integrated”), clearly referring to the series of high-profile integration (Integratsioon) policies and programs established in Estonia, to “solve the problem” of Russian-speaking minorities (Siiner, Koreinik, and Brown Reference Siiner, Koreinik and Brown2017, 2). Integration activities include Estonian language-learning clubs, cultural events, and other grassroots initiatives, primarily focusing on language differences as the main cause of segregation (Astapova Reference Astapova2021, 2). Thus, according to Gorelov (Reference Gorelov2020, 72), the adjective “integrated” (“интегрированый”) is commonly used by Russophone Estonians, somewhat negatively, to describe those who do not commemorate May 9th and/or accept the Estonian, rather than Russian, Second World War narrative.

Nublu seemingly reinforces views that language is an obstacle to successful integration in the line “Me suhtluses on seisak nagu rikkis valgusfoor” (“Our communication is at a standstill like a broken traffic light”), however he also demonstrates optimism that ethnic Estonians and Russophones will, like he and Oksana, eventually integrate “like Gin and Pink Schweppes” (“Gin ja roosat värvi Schweppes”). It is important here to mention the influence of Nublu’s co-performer in the song, Gameboy Tetris (real name Pavel Botšarov), who has been actively involved in Integratsioon (Integration) projects, including “Karma,” an Estonian language rap opera performed at Narva’s Vabalava cultural center (Integratsiooni Sihtasutas 2020). Botšarov was born in Haapsalu, a coastal town in western Estonia, to a Russophone Estonian family and grew up in Tallinn’s predominantly Russian-speaking Lasnamäe district, but only became a “full” Estonian citizen in November 2020, when he exchanged his grey “alien” passport for an Estonian one (Pihl Reference Pihl2020). In February 2021, Botšarov received The Order of the White Star, 5th Class from President Kersti Kaljulaid, recognizing his positive contribution to Estonian society (Wright Reference Wright2021). While “für Oksana” should not be understood as a component of state-led approaches to integration, Botšarov’s involvement highlights the interplay between these top-down initiatives and broader societal discourses expressed through popular cultural mediums including music.

The third step of Fairclough’s (Reference Fairclough1992) framework considers discourses as social practice, reflecting existing power structures in societies. Within Estonian national discourses, Russophone Estonians are often understood as an “underclass” (Kesküla Reference Kesküla2015), generally holding lower economic status than ethnic Estonians (Aasland and Fløtten Reference Aasland and Fløtten2001, 1024). “für Oksana” may partly reinforce these existing power dynamics, particularly in the Russian language lines alluding to negatively connoted behaviors including heavy drinking (“Давайте выпьем виски” – “Let’s drink whiskey”) and a fondness for money (“Твой папа любит деньги, деньги, деньги” – “Your father loves money, money, money”), which may be stereotypically associated with “gopniki,” as described above (Loeb Reference Loeb2020). However, money is also a common theme in hip-hop music and culture more generally, where having a lot is considered a clear marker of success (George Reference George, Biddle and Knights2016, 100). In “für Oksana,” despite their differences, loving money seemingly provides a point of connection between ethnic Estonian Nublu and Russophone Oksana. Nublu sings, “We both love money” (“Мы вместе любим деньги, деньги, деньги”), while Gameboy Tetris admits he goes to Ivangorod to buy petrol, specifically Russian Lukoil, because it is cheaper there (“Я тоже, заправюсь в Ивангороде – там дешевле (Лукойл!)”).

The song’s Estonian language lyrics repeat common understandings of Russian culture and lifestyles in hegemonic Estonian discourses, including assumptions Russians decorate their homes with carpets on the wall (“Vaibad sinu seinal”) and drink a lot of alcohol (“Lärmakad joogised tüdrukud meeldivad meeletult” – “These noisy, tipsy girls like it crazy”). Yet Nublu also alludes to a fascination with, and perhaps orientalization of, Russophone Estonians by ethnic Estonians with the line “Sind vaatan, kui kassahitti Coca-Cola Plazas” (“I watch you like a blockbuster in Coca-Cola Plaza”), where Coca-Cola Plaza is an entertainment and cinema complex located in Tallinn. The film metaphor is extended here, seemingly representing Estonian society, where Oksana, as a Narvian, is something exotic, to be observed from afar and unable to be fully included (“Ma tean, et selles filmis ei saa lüüa kaasa” – “I know you can’t get involved in this movie”). Nublu’s desire for a happy ending to his and Oksana’s story (“Tahan uskuda, et lõpp on õnnelik” – “I want to believe that the ending will be happy”), seems a clear metaphor for hopes integration between ethnic Estonians and Russophones will eventually prove successful.

Yet, “für Oksana” itself may constitute evidence of organic, grassroots forms of integration having already taken place. The consistent and fluent codeswitching between Russian and Estonian throughout the song appears to demonstrate ways the two languages, and thus two “parallel societies,” interact in everyday practice. As Verschik (Reference Verschik2019, 6) notes, for young Russophone Estonians in particular, borders between the Russian and Estonian languages are not as strictly delineated as for previous generations. In multi-lingual households, work, and educational contexts, the two languages are often used interchangeably (Karpava Reference Karpava2018, 114), with incorporation of Estonian words into otherwise Russian written and spoken communication “unexpected but not inappropriate” (Verschik Reference Verschik2019, 6). The line “Let’s speak English” (“Поговорим по английски”) alludes to the increasingly common practice of using English as a lingua franca in interactions between Russophone Estonians and ethnic Estonians, in situations where neither has mastered the other’s mother tongue (Astapova Reference Astapova2021, 4). English’s growing role in bridging this communication gap results both from increased international and domestic mobility and employment benefits it provides, as well as Estonian educational policies, which discourage the titular majority from learning Russian (Toomet Reference Toomet2011, 531).

The next section adds to this examination of the lyrics of “für Oksana” via a Multi-Modal Discourse Analysis (MMDA) of the settings, symbols, and characters presented in the song’s accompanying video.

Music Video

The video accompanying “für Oksana” was a huge factor behind the song’s success. Its director, artist Marta Vaarik, aimed to appeal to young people in Estonia and capture the overarching theme that “imagination can be more beautiful than reality” (Vaarik as cited in Mõttus Reference Mõttus2019). Accounting for all the different modes of expression inherent in the music video including gestures, speech, still and moving images, writing, and music (Kress Reference Kress, Gee and Handford2013, 36) is beyond the scope of this article. Instead, following Ledin and Machin’s (Reference Ledin and Machin2018) approach to the visual analysis of video-based materials, this article examines the music video for “für Oksana” according to three broad themes: settings, symbols and characters.

Settings

In hip-hop videos, identification with specific, usually urban and run-down, localities contributes to the construction of artists’ “authentic” images (Signer and Balaji Reference Sigler and Balaji2013, 336; Rose Reference Rose1994, 10). While showing pride in places of origin is common in hip-hop videos, being “real” is also an important way of demonstrating credibility, hence the tendency to portray locations as candidly as possible (George Reference George, Biddle and Knights2016, 101). The video for “für Oksana” is filmed predominantly in Narva, with some additional scenes shot elsewhere in Ida-Virumaa, the county where Narva is situated (Kaldoja Reference Kaldoja2019). Scenes therefore depict local settings and landmarks, clearly identifiable to Narvians as important in local discourses. This section examines four of the most used settings in the video, each of which contributes to the performance of Russophone Estonian identity.

The first is Kreenholm (figure 1), an abandoned textile factory complex, which as discussed above, plays a prominent role in local conceptualizations of Narvian identity. As subjects of Pfoser’s (Reference Pfoser2014, 274) ethnographic study of the city highlight, Kreenholm is something of a physical symbol of Narva’s importance during the Soviet period and its subsequent decline following Estonian independence. Kreenholm features in several scenes of the video, including in the background as a limousine containing Nublu crosses a bridge, and as the site of choreographed dance scenes involving young people (figures 1-3). The emphasis on youth in these scenes, embodied by these dancers, seems to reflect Kreenholm’s continued relevance, despite its lengthy period of disuse, to new generations of Narvians. Constant speculation about Kreenholm’s future is inextricably linked to prospects, or lack of, for young people in the city to find work and purpose. Yet, Kreenholm is equally considered a “symbol of hope” for the city’s future and a “citadel of innovation and industrial change” (Narva is Next 2019, 15), with plans for its redevelopment featuring prominently in Narva’s (ultimately unsuccessful) bid to become 2024 European Capital of Culture.

Figure 1. Kreenholm 1 (source: Nublu 2019)

Figure 2. Kreenholm 2 (source: Nublu 2019)

Figure 3. Kreenholm 3 (source: Nublu 2019)

A second prominent setting is a series of canals in the east of the city, known locally as “Narva Venice” (Martínez, Reference Martínez2020, 78). Narva Venice is home to hundreds of seemingly makeshift structures used for storage, summer residences, and recreational activities, and is considered an integral feature of the city’s cultural and social life (Whyte Reference Whyte2021). The “für Oksana” depicts Narva Venice as a place where people chase around on jet skis and local characters of all kinds gather together to celebrate life (figures 4-6). The use of jet skis in these scenes may hint at the kind of glamorous lifestyle typical of many hip-hop and rap videos, in which performers often appear with expensive cars, both as symbols of their financial success and masculinity (Hess Reference Hess2007, 8), and glorifying conspicuous consumption (Balaji Reference Balaji2009, 26). However, here, the deliberate juxtaposition of tropes “authentic” hip-hop cultural tropes with the unlikely surroundings of Narva, additionally suggest a playful sense of self-awareness bordering on parody. In one Narva Venice scene, Nublu dances toward a shack, to the bemusement of local people sitting eating a picnic. A local then presents Nublu with a life vest (figure 7), which he holds aloft before putting it on and jetting off into the water. Here, as in several other examples in the video, humor appears to be a “localization tool” used to reduce the sense of dissonance between traditionally articulated hip-hop identities (Tervo and Ridanpää Reference Tervo and Ridanpää2016, 617) and the local Russophone Estonian context of “für Oksana.”

Figure 4. Narva Venice 1 (source: Nublu 2019)

Figure 5. Narva Venice 2 (source: Nublu 2019)

Figure 6. Narva Venice 3 (source: Nublu 2019)

Figure 7. Nublu at Narva Venice (source: Nublu 2019)

A third location featured is the inside of a typical “Soviet” apartment. Within Estonia, there is a tendency to associate such apartments, usually located in prefabricated apartment blocks built in the 1950s, known as “Khrushchyovkas,” as physical and visible signs of the “unnatural” period of Soviet occupation (Wright Reference Wright2019). Exemplifying this was the 2017–19 museum exhibition “No Bananas: A Time Travel to the Soviet Everyday Life,” initially held at the Tallinn TV Tower and later relocated to the city’s central Baltijaam railway station, which featured “a realistic replica of an average Estonian apartment in the 70s-80s style” (Teletorn.ee, April 26, 2017). According to the exhibition’s official website: “Those who remember that period can recall the absurdity of it, for the younger people it is something totally exotic” (Teletorn.ee, April 26, 2017), yet such apartments are still reasonably commonplace throughout Estonia and in other former Soviet countries (Polese Reference Polese2019). As Polese (Reference Polese2019) argues, the exhibit’s location in proximity to the newly constructed Tallinn railway station and fashionable hipster district of Telliskivi visibly contributes to promulgating this collective understanding of these apartments as “absurd” and “exotic” artefacts from the past rather than features of present-day Estonia.

The apartment scenes in “für Oksana” can be divided into two separate types: first, those in which Gameboy Tetris raps whilst sitting behind a table in the kitchen and second, those involving Oksana’s family enacting aspects of day-to-day life. In all the apartment scenes, items of furniture and decorations visible such as a “landscape painting, colourful wooden bowls, [and] ornamental curtains” reflect “Russian” rather than “Estonian” tastes (Martínez Reference Martínez2020, 84). However, in scenes featuring Gameboy Tetris, a collection of souvenir magnets collected from different European countries, including Malta, Finland and Greece, are perhaps a subtle reminder that Narva too, is in Europe. Interestingly, there is also a magnet from Ivangorod (Russia) amongst the collection.

Food plays a prominent role in the apartment scenes. In one scene, Oksana and her family eat pickled cucumbers from a jar and in others they drink shots of brightly colored alcohol (figure 8), while the kitchen table Gameboy Tetris sits behind is also filled with food and drinks (figure 9). For Polese, Seliverstova et al. (Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Kerikmae and Cheskin2020, 1016), food-related practices may act as shortcuts for performing elements of national identity in everyday life. In the Estonian context, patriotic food packaging and branding has been identified both a source of pride for all the country’s citizens, including Russophones, and a means of distinguishing truly Estonian food from that which is Soviet (Polese, Seliverstova et al., Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Kerikmae and Cheskin2020, 1025, 1028). As Polese (Reference Polese2019) reflects, the displaying of certain food items commonly consumed throughout Estonia in the present day, as relics of the past, in Tallinn’s “No Bananas” exhibition indicates desires to present the Soviet time as further away from the present than it actually is. Thus, while the pickles and alcohol Oksana and her family consume in the video may connote Russian, rather than Estonian identity, in practice, ethnic distinctions between foods consumed are less tangible (Polese, Seliverstova et al. Reference Polese, Seliverstova, Kerikmae and Cheskin2020, 1022). Perhaps hinting at the fact Narvians also consume Estonian products, two bottles of Crafter’s Gin can also be seen, one on the table in front of Gameboy Tetris and another behind him. Crafter’s is an Estonian brand, which describes the importance of “Our heritage – our traditions and the way we Estonians do things” (“Crafter’s Gin – Our Story” 2021) on its website, explicitly connecting itself to Estonia’s desired Nordic identity and orientation. Thus, unlike the “No Bananas” exhibition, “für Oksana” uses elements of exaggeration and parody to recast stereotypical understandings of Russophones held in Estonian society, while also subtly highlighting commonalities with the hegemonic titular culture.

Figure 8. Oksana Eats Pickled Cucumbers (source: Nublu 2019)

Figure 9. Gameboy Tetris Apartment Scene with Food (source: Nublu 2019)

A fourth important setting in the “für Oksana” video is a complex of private garages. Similar to the makeshift structures in Narva Venice, garage complexes in Narva are not only used for storage, but also as centers of social interaction, particularly for the city’s male population (Martínez Reference Martínez2020, 78; Tuvikene Reference Tuvikene2010, 520). During the Soviet period, garage complexes were built in much greater number in Soviet than Western European cities (Tuvikene Reference Tuvikene2010, 513), with many in Estonia surviving both independence and re-orientation toward Europe (Tuvikene, Reference Tuvikene2010, 510). In the “für Oksana” video, Narva’s “inland” garages feature as places where young males in casual clothing spend time playing football. On the garage roofs, players from the city’s top football club JK Narva Trans wave flags containing the team’s logo and play their own game, literally, and perhaps metaphorically, at a higher level than the ordinary Narvians below (figure 10). While garages are presented here as something typical of Narva, similar complexes prevail in Estonia’s other major urban areas Tartu and Tallinn (Tuvikene Reference Tuvikene2010). Thus, there appears to be a similar paradox here to that of the “Soviet” apartment discussed above. While often considered relics of the “unnatural” Soviet period, both continue to exist throughout Estonia as parts of broader development processes, despite discursive efforts to consign them to the Soviet past as features exclusive to the “rupture.”

Figure 10. JK Narva Trans Players and Garage Complex (source: Nublu 2019)

Symbols

As Billig (Reference Billig1995, 38) states, to survive, nations and identities require constant reminders in the form of symbols or, in both metaphorical and literal senses, “flags.” Perhaps the most important symbol signifying Russophone as distinct from ethnic Estonian identity is the St. George’s ribbon (Gorelov Reference Gorelov2020, 74). The ribbon’s enduring significance as an identity marker for young Russophone Estonians, who have no personal memories of the Soviet Union nor the Second World War, provides both links to Russian historical narratives and highlights a point of contention with hegemonic Estonian discourses. Gorelov (Reference Gorelov2020, 75) for instance, argues Russophone Estonians not wearing the ribbon on May 9th (Russian Victory Day) can be negatively perceived in the Russophone community as actively forgetting the symbol’s meaning and thus threatening senses of collective identity. While previously tolerated, albeit somewhat reluctantly, by the Estonian state, the ribbon has long been seen as a symbol of the aforementioned disloyalty suspected of Russophone Estonians. However, following Russia’s military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the ribbon became more explicitly acknowledged as a symbol of support for Russia, and was banned from display during May 9th commemorations, with the Estonian police and border guard also reportedly refusing truck drivers who declined to remove the symbol from their vehicles, entry to the country (Whyte Reference Whyte2022).

Mirroring the song’s lyrics, which mention the St. George’s ribbon intertwined in Oksana’s hair (discussed above), the video includes a scene where young people dance at the Kreenholm factory wearing the orange and black ribbons as headbands (figure 11). The style in which the ribbons are worn in the video, resembling ways rebellious teenagers might wear their school ties, is consistent with the deliberately playful approach taken by director Marta Vaarik to a famously difficult aspect of Russian-Estonian relations (Vaarik as cited in Korsten 2019). The ribbon also appears in the “Soviet apartment” scenes pinned to the wall behind Gameboy Tetris, contributing to this location’s presentation as “Russian” rather than Estonian.

Figure 11. Dancers Wearing St Georges Ribbons as Headbands (source: Nublu 2019)

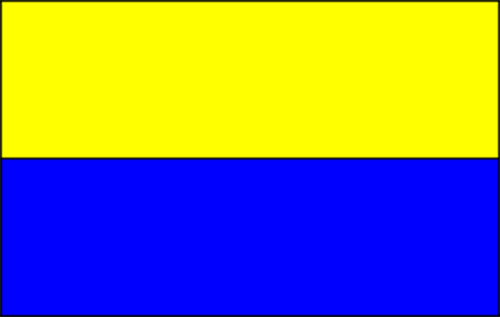

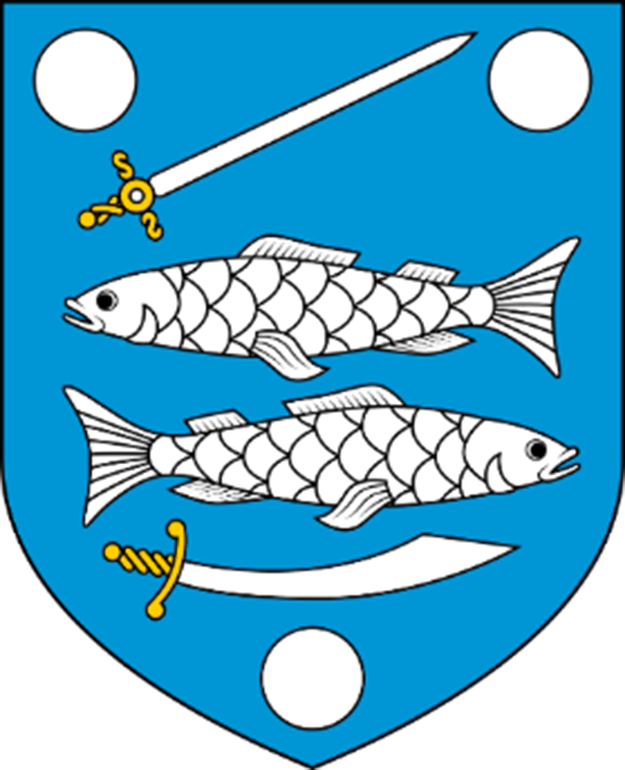

Though less explicit, clothing Oksana and Nublu wear also appears to reference two important local Narvian symbols. Towards the end of the video, after Nublu finds Oksana, they stand together in the street (figure 12). Nublu’s yellow hooded top, combined with Oksana’s dyed blue hair are suggestive of the blue-yellow flag of the city, while Oksana’s shirt, visible underneath her jacket, contains pictures of fish, resembling those on Narva’s coat of arms (figures 13–14). In a sense, this image appears indicative of the harmonious co-existence of apparently incompatible elements of identity, depicted literally as the characters of Nublu and Oksana, but perhaps also metaphorically as an embodiment of the duality of Narvian identity itself.

Figure 12. Nublu and Oksana as the Narva Flag and Coat of Arms (source: Nublu 2019)

Figure 13. Flag of Narva (source: Flag of Narva Town 2005)

Figure 14. Narva Coat of Arms (source: Coat of Arms of Narva Town 2006)

Characters

The “für Oksana” video depicts a range of characters, ostensibly as playful and comic versions of archetypes one may expect to encounter in Narva. Most actors in the video are Narvians (Korsten 2019), with exceptions including Nublu, Gameboy Tetris, Karin Nahkur (who plays Oksana), and Anu Saagim, an Estonian actor and personality known for appearing in commercials during the Soviet period, featuring here as Oksana’s mother (Toomemets Reference Toomemets2019). While a detailed analysis of all the video’s characters is beyond the scope of this article, this section outlines the broader themes in their portrayals, beginning with representations of men and then women.

Oksana’s family consists of predominantly male characters, each of whom perform clichéd aspects of the “gopniki” persona including play fighting, drinking alcohol, eating jars of pickled cucumbers and acting in sexually aggressive ways toward women (figure 15). The exaggerated performance of these personas, which are strongly associated with the Russian-speaking, rather than ethnic Estonian population, can be interpreted both as a self-aware celebration of Russophone Estonian identity, while also highlighting the absurdity of preconceptions held about Narvians in Estonian society. That the actors playing members of Oksana’s family are Narvians who have gained local fame from appearing in the video (Ida Repost 2019), suggests the performances are knowingly ironic in ways relatable to locals.

Figure 15. Oksanas Family

The most prominent female character in the video is Oksana, as the narrative explores the differences between the male protagonist’s preconceived notions of a Russophone Estonian woman from Narva and the reality (Kaldoja Reference Kaldoja2019). Oksana first appears dressed in all white, with a long, blond wig, body suit, and high heels, riding a white horse (figures 16–18). This fantastical vision of Oksana contrasts with subsequent scenes, revealing her multi-faceted persona and demonstrating the complexity of reality in comparison to exoticized and orientalized understandings of Narvians in Estonian popular imagination (Makarychev Reference Makarychev2021, 68; Mõttus Reference Mõttus2019). Thus, Oksana adopts several “characters” during the video, including dancer and a female gopnik, who is almost indistinguishable from her male counterparts. Director Marta Vaarik additionally stresses the importance of a scene where Oksana gives one man a bloody nose after he touches her inappropriately, showing women do not have to tolerate such behavior from men (Kaldoja Reference Kaldoja2019).

Figure 16. Oksana Imagination versus Reality 1

Figure 17. Oksana Imagination versus Reality 2

Figure 18. Oksana Imagination versus Reality 3

Conclusions

This article examined the discursive expression, negotiation, and performance of Russophone Estonian identity in the song “für Oksana” by Nublu featuring Gameboy Tetris and its accompanying music video. A Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) of the song’s lyrics demonstrated ways the basic love narrative between an Estonian man and Russophone girl acts as a metaphor for experiences of integration processes between ethnic Estonians and Russophones since Estonian independence. The analysis demonstrates that, on the surface, the song’s portrayals of Russophone Estonians may appear to reinforce stereotypical understandings of the community stemming from existing power relations in Estonian society. However, a more detailed examination highlights how these stereotypical tropes are invoked to present an alternative image of Russophone Estonians, both sensitive to local identity issues and encouraging a lighter approach to tackling points of contention with hegemonic Estonian discourses surrounding integration.

While claims by the video’s director Marta Vaarik that “für Oksana” had done more for Russian-Estonian relations than the Estonian government had for several decades (Mõttus Reference Mõttus2019) may be self-aggrandizing, music, particularly the visual components evident in videos and performances, clearly seems to provide a potentially valuable platform to present, discuss, and negotiate integrations issues in Estonia. This potential has not escaped the notice of state actors, with several recent top-down initiatives utilizing music to bridge gaps between the two apparently disparate communities. In August 2021, not only did Narva host the fourth edition of its annual “Station Narva” music festival (Station Narva 2021), featuring Estonian and international artists, but also the “Drive Slowly Over The Bridge” singing party, which, mirroring similar events in Tallinn and Tartu, marked the 30th anniversary of Estonian re-independence (“Singing Party ‘Sõida tasa üle silla’ (Narva)” 2021). The latter notably included both Estonian and Russian language songs, with singers and presenters on stage codeswitching between the two languages. This contrasts with hegemonic versions of Estonian identity showcased in the Laulupidu (Song Celebration), a festival held every five years, and heavily woven into national re-independence narratives, which some see as an instrument of Estonian language promotion (Pawłusz Reference Pawłusz2017), tool to foster national unity (Kuutma Reference Kuutma1998, 2), and method of hegemonic cultural transmission (Raudsepp and Vikat Reference Raudsepp and Vikat2009).

Following Russia’s full-scale military invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and with fears of potential unrest amongst Estonia’s Russophone population, the annual Tallinn Music Week was reorganized at the final hour to include a full program of musical performances and cultural events in Narva (BBC Radio 4, May 19, 2022). President Alar Karis opened the Narva events with a speech invoking images of musicians performing in air raid shelters and amongst the ruins of buildings in Ukrainian cities, and emphasizing music’s power to “cultivate empathy and compassion” (Karis, Reference Karis2022). Later that day, special guest Nublu joined Gameboy Tetris on stage at the city’s Vabalava cultural center for a rendition of “für Oksana” (BBC Radio 4, May 19, 2022).

Equally notable were performances in Narva on the same bill by high-profile ethnic Estonian performers, including Curly Strings and Trad.Attack! The former, whose music is a staple of modern-day national cultural events in Estonia, previously played 30 concerts in small Estonian towns and villages as part of 2018’s year-long “EV100” celebrations marking the 100th anniversary of the foundation of the first Estonian Republic in initiative organized in cooperation with the Government Office (Riigikantselei) (Postimees Kultuuritoimetus 2018). The latter received an award in 2020 from the Estonian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for their success in introducing Estonia to international audiences abroad through music (Republic of Estonia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2020).

Such examples further highlight the interplay between top-down initiatives and bottom-up approaches to integration and nation building through music in Estonia, suggesting several fruitful areas for future research. Of additional interest would be examinations of ways hip-hop acts as a form of non-hegemonic identity expression in other countries, with similarly significant minority populations or where states have consciously utilized music and other forms of popular culture as part of unifying or nation building strategies. It would also be beneficial to supplement the findings of this article with ethnographic research, foregrounding Russophone Estonians’ personal experiences of integration and nation building processes.

Financial Support

This work was supported by the FATIGUE project under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under grant agreement No. 765224.

Disclosures

None.

Appendix A – Nublu x Gameboy Tetris “für Oksana” Song Lyrics (Nublu 2019)

::REF:: А это жизнь, это карма

Привет, город Нарва

Я лечу к тебе kolm tundi veel

Ja seal oleme vaid ainult me koos

А это жизнь, это карма

Привет, город Нарва

Ja mu väike venelanna, tead ma satun siia harva

Siis kui Balti jaamast välja läheb rong.

südalinnas, agulis, mu tunded kinni vagunis,

ma esmapilgul nägin ainult seda sinu tagumist,

sa särad nagu paabulind ja ründad nagu kotkas,

aga südametesõjas sain ma õla peale pagunid,

давайте выпьем виски, поговорим по английски,

слышь!

they’re not gonna get us, not gonna get us

нас не догонят!

sind valvata võin öösiti - ночной дозор,

kuid me suhtluses on seisak, nagu rikkis valgusfoor,

essa kord läks aia taha,

pohhui proovin veelkord,

saame kokku seal kus Kreenholm!

ma tean, see Georgi lint su juuste sisse

jäädavalt on põimunud,

kui murumängud toimunud

ja sina-mina lõimunud,

vaibad sinu seinal,

gin ja roosat värvi Schweppes,

ma nägin seda ette, nagu Aleksander Šeps

::REF:: А это жизнь, это карма

Привет, город Нарва

praktiliselt nagu maletaja Paul Keres

kuigi ise pole pärit siit, võitleja olla geenides

ka minu kodus, nagu siin, räägiti samas keeles

ja need lärmakad, joogised tüdrukud meeldivad meeletult!

Твой папа любит деньги, деньги, деньги

Я тоже, заправюсь в Ивангороде - там дешевле (Лукойл!)

Мы вместе любим деньги, деньги, деньги

И все же за мой счет всему Ro Ro, всему Модерну. (Домой!)

Пора домой! как пели Сектор Газа,

Sind vaatan, kui kassahitti Coca-Cola Plazas.

ma tean, et selles filmis ei saa lüüa kaasa

tahan uskuda, et lõpp on õnnelik, ja rahvas ütleb…

REF: А это жизнь, это карма Привет, город Нарва

Я лечу к тебе kolm tundi veel

Ja seal oleme vaid ainult me koos

А это жизнь, это карма

Привет, город Нарва

Ja mu väike venelanna, tead ma satun siia harva

Siis kui Balti jaamast välja läheb rong.

Appendix B - Nublu x Gameboy Tetris ‘für Oksana’ Song Lyrics. Nublu. 2019. English Translation

https://lyricstranslate.com/en/f%C3%BCr-oksana-oksana.html-0

But it is life, it is karma

hello NarvaFootnote 1 town

I’ll fly to you, three more hours

and there we will be together only you and me

but it is life, it is karma

hello Narva town

and my little Russian girl, you know I don’t come here often

when the train departs from the Balti stationFootnote 2

In the city center, slum, my feelings trapped in a wagon

at first I saw only your bottom

you shine like a peacock and attack like an eagle

but in the war of hearts I got the epaulettes on my shoulder

come on let’s drink whiskey

so we will speak English

hey listen

they’re not gonna get us, not gonna get us

not gonna get usFootnote 3

I can guard you at night – The Night Watch

there is a pause in our communication - like a broken traffic light

first time was a mess, who cares, let’s try again

let’s meet up at KreenholmFootnote 4

I know that the St. George’s ribbonFootnote 5 has

permanently intertwined with your hair

when the games on grass have taken place

and you and I have integrated

carpets on your wall, Gin and pink Schweppes

I already saw it coming like Aleksandr ShepsFootnote 6

Withdraw the amateurs

But it is life, it is karma

hello Narva town

I fly with you for three more hours

and there we will be together only you and me

but it is life, it is karma

hello Narva town

and my little Russian girl, you know I don’t come here often

when the train departs from the Balti station

Practically like Paul Keres

even though I am not from here, there is a fighter in my genes

also at my home, like here, they spoke the same language

and these noisy, tipsy girls like it crazy

your father loves money, money, money

me too, I refuel in Ivangorod, Lukoil is cheaper there

together we love money money money

and yet at my expense Ro Ro, even Modern

(home)

time to go home! Cocktail and the Gaza Sector

I watch you like a blockbuster in Coca-Cola Plaza

I know you would like to be in this movie

I want to believe that this movie has a happy ending

And the crowd will say

But it is life, it is karma

hello Narva town

I fly with you for three more hours

and there we will be together only you and me

but it is life, it is karma

hello Narva town

and my little Russian girl, you know I don’t come here often

when the train departs from the Balti station

Nublu Game Boy Tetris