1. INTRODUCTION

‘We are in the midst of a climate emergency which poses a threat to our health, our planet and our children and grandchildren's future’, London Mayor Sadiq Khan told The Guardian in December 2018, upon declaring a climate emergency in the capital city of the United Kingdom (UK).Footnote 1 Over 2,000 ‘climate emergency declarations’ have been issued by governments around the world, covering over one billion people.Footnote 2 These declarations are a specific step taken by governments to acknowledge the severity of global climate change and their own responsibility to act in response. They track the increasingly urgent projections of scientists, global waves of youth climate strikes, and repeated experiences of extreme events amplified by climate change – catastrophic flooding, engulfing wildfires, deadly heatwaves – around the world.

Framing climate change as an emergency is one of many ways of understanding this transnational and all-encompassing phenomenon. Researchers have investigated the strategic potential of various frames (such as economic and health) for advancing climate policy.Footnote 3 Legal scholars have analyzed alternate frames that emerge through climate litigation.Footnote 4 Climate emergency declarations present a new frame and a new site for legal analysis. Climate emergency declarations seem to track the new reality of repeated, frequent extreme events, and thus might be seen as laudable instruments in how they recognize sound scientific evidence on climate impacts and require governments to take steps to fulfil commitments many have already made through strategic plans, legislation or international agreement. Yet, declarations of emergency have always played an uncomfortable role in public law. Any attempt to invoke the language of emergency should be scrutinized carefully, especially by legal scholars, in the light of the long history of emergencies undermining rule-of-law and human rights commitments.

Climate emergency declarations present a public law puzzle. They are not declarations of states of emergency – a conventional legal ‘tool’ employed by the state for responding to an extreme event such as a wildfire; nor are they mere rhetoric. They have attracted scholarly attention, but not yet in law. In the light of their ambiguous status, one temptation for public law scholars might be to dismiss these declarations as irrelevant or incoherent. However, it is the transnational and legally ambiguous nature of climate emergency declarations that creates a unique opportunity to interrogate common assumptions about emergencies and how they are regulated in law.

This article argues that climate emergency declarations act as a ‘spotlight,’ illuminating latent assumptions about emergencies held within public law scholarship. The disruption of emergencies can ‘bring to the surface otherwise implicit aspects of normal politics’Footnote 5 or highlight background systemic discrimination and oppression.Footnote 6 When reviewed closely, these climate emergency declarations reflect back a set of paradoxes about how emergencies are governed in law. These paradoxes productively complicate long-held and over-simplified assumptions about emergencies contained in public law and, in so doing, allow us to see the complex ways in which public law regulates emergencies.

This article proceeds as follows. Section 2 introduces the phenomenon of climate emergency declarations, the puzzle they present for public law scholars, and my methodology for analyzing these declarations. Section 3 addresses a set of perennial concerns and questions that emergencies provoke in public law scholarship. Three sets of questions emerge: (i) how emergencies are defined; (ii) how time regulates and contains emergency power; and (iii) who responds to emergencies and how. Section 3 also analyzes declarations of climate emergency and identifies definitional, temporal, and exceptionality paradoxes contained within them.

The article does not present a simple resolution to the legally ambiguous nature of climate emergency declarations. Rather, it insists on highlighting the nuance, variation and complexity contained in these declarations. Indeed, such declarations arguably underline the necessity for a nuanced and multifaceted understanding of emergencies as we contemplate the role of law in governing a climate-disrupted world.

2. THE EMERGENCE OF CLIMATE EMERGENCY DECLARATIONS

The notion of climate emergency moved to the mainstream in 2019.Footnote 7 Climate emergency declarations occupy many of the intersections that characterize transnational environmental law: the intersection between non-governmental and governmental action, the intersections of multilevel governance, and the intersection between law, policy and politics. Their emergence as a transnational phenomenon began in 2016 with campaigns by non-governmental actors based in Australia successfully targeting municipal governments worldwide. An example of ‘contagious environmental lawmaking’,Footnote 8 these declarations spread from the local to national and subnational governments, causing regional and international actors as well as other institutions (such as universities) to follow suit.Footnote 9 The Guardian estimates that at least 38 countries have declared a climate emergencyFootnote 10 and a global database reports that nearly 2,000 municipalities have done the same.Footnote 11

Climate emergency declarations proliferated during 2019, alongside global student climate strikes and on the heels of the 2018 Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Global Warming of 1.5°C. This report detailed the anticipated catastrophic impacts of exceeding a 1.5°C increase in average global temperature, but it also projected that deep and rapid reduction of emissions to 45% below 2010 levels by 2030, reaching net zero by 2050, would be consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C.Footnote 12 It further offered four model pathways for achieving these reductions.Footnote 13 The IPCC's reporting on this narrow window of opportunity for concerted action to avoid catastrophe helped to propel activism around the climate emergency.

The promise of framing climate change as an emergency is that it will provoke government action to both mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and further reduce vulnerability to climate impacts through adaptation. In a widely cited report for local governments, Spratt writes:

The purpose of climate emergency declaration campaigning is to accelerate sustained and meaningful action by all levels of government, and for people globally to engage with the challenge of avoiding catastrophic climate change and restoring a safe climate.

The goal is to provide maximum protection for the local community and for people, civilisation and species globally, especially the most vulnerable, and to enable local communities to be strong in the face of any unavoidable dangerous climate impacts.Footnote 14

Spratt, and others, identify a number of features of ‘emergency mode’, which serve as a way of breaking from a business-as-usual approach to governing. Climate emergency declarations, in their view, have the virtues of taking seriously the worst-case scenario and presenting a clear purpose for governmental action.Footnote 15

Climate emergency declarations have also been critiqued by some who take seriously the climate challenge. For instance, Murphy argues that the call for climate emergency declarations is ‘at best an ethically dubious move’ because of the grim historical record of states of emergency and the reification of sovereign powers.Footnote 16 Indeed, much of the literature that favourably considers climate emergency discourse draws directly on wartime responses in support of climate emergency action.Footnote 17 Hulme expands on this critique, observing that the reductive logic of emergency – intended to provoke urgent and coordinated action – does not help us in addressing the multitude of interlinked global challenges we face (such as climate change, biodiversity loss, socio-economic inequality), which demand ‘plural goals and political creativity’.Footnote 18 Indigenous scholars similarly worry that climate emergency discourse crowds out alternate narratives and justifies measures which retrench colonial power (for example, the siting of ‘green’ energy projects).Footnote 19

Scholars have analyzed the use of emergency rhetoric as a tool for social change in other fields, addressing similar concerns. While recognizing the long history of oppressive emergency actions, Anderson notes that emergency discourse is often called upon by equity-seeking organizations to make urgent ‘unbearable or barely bearable conditions into ethical or political scenes demanding response’.Footnote 20 In these cases, he argues that emergency declarations may be seen as hopeful because emergencies ‘are events or situations where action can still make a difference’.Footnote 21 Similarly, Arbel observes that treating the outcomes of unjust systems as exceptional helps to diffuse responsibility and perpetuate an unjust status quo.Footnote 22 Turning to Arendt, Arbel argues that, instead, a declared ‘emergency’ must provoke the needed reflection (and action) on the structural causes of the declared emergency that have been laid bare.Footnote 23

In contrast, public law literature has thus far ignored climate emergency declarations: they are not declarations of states of emergency. Unlike a conventional declared state of emergency, climate declarations are not orders made by the executive under pre-existing emergency management legislation. Rather, they are statements made predominantly by legislative bodies (Parliaments, legislatures, and municipal councils),Footnote 24 sometimes accompanied by legislative reform and at other times not. Further, these declarations do not authorize the use of measures typically associated with emergency response, such as evacuation or appropriation.Footnote 25 While legal scholarship has begun to adopt emergency discourse as an appropriate framing of the challenge of climate change,Footnote 26 courts have yet to rule on climate emergency declarations.Footnote 27

The uncertain status of climate emergency declarations in public law presents something of a puzzle. They are neither conventional declarations of emergency nor mere rhetoric. They are simultaneously seen as effective, dangerous, and also capable of being ignored. The remainder of this article engages with the uncertain status of climate emergency declarations. It does so not as an object of law reform nor through external critique. Rather, it investigates the potential of these declarations to illuminate existing assumptions about emergencies contained in public law.

The article undertakes a close reading of a subset of climate emergency declarations. It addresses declarations issued in the UK, Canada, Australia, and Aotearoa/New Zealand. The selection of these jurisdictions is based predominantly on the shared common law tradition dominant in all countries.Footnote 28 This shared common law tradition is reflected in literature on emergency powers and the law, which frequently incorporates judicial decisions and other legal developments from all four jurisdictions.Footnote 29 I have not included the United States (US) in this analysis in order to avoid the ‘prism of the American experience’,Footnote 30 which refracts uniquely on both emergency powers and climate change law and policy.

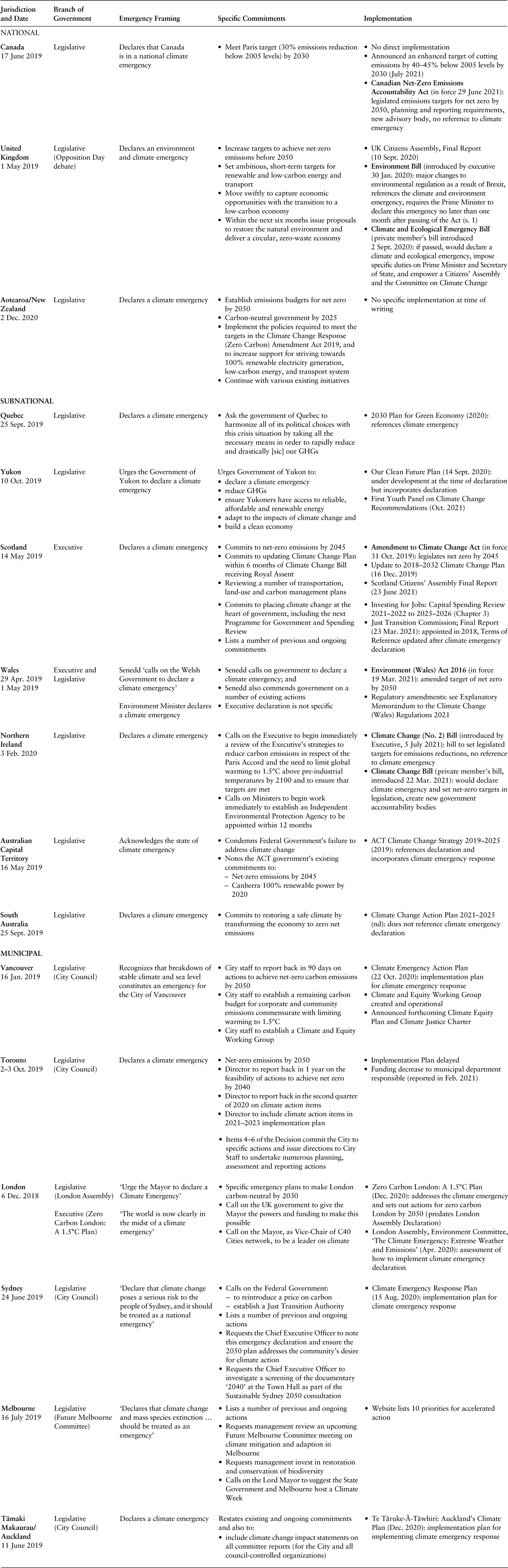

For each country, I have included and analyzed all declarations issued at the national and state/provincial/territorial levels. I have also included declarations for major cities within each jurisdiction.Footnote 31 Table 1 (at the end of this article) summarizes the key attributes of the declarations and their implementation. In total, 16 jurisdictions have been included in this study. While climate emergency declarations are the product of a transnational movement, and patterns do emerge, the analysis that follows shows that these declarations are varied and textured, and contain complex dialogues about emergencies in public law, which are not easily generalized.Footnote 32

Table 1 Comparative Features of Climate Emergency Declarations

3. EMERGENCIES AND PUBLIC LAW

Emergencies feature prominently in legal theory, constitutional law and disaster law. While different questions drive each of these areas of literature, they converge on a core set of concerns: (i) how emergencies are defined (the definitional challenge); (ii) how time regulates and contains emergency power (the temporal challenge); and (iii) who responds to emergencies and how (the exceptionality challenge). For legal theorists, these challenging issues of definitions, time and exceptional measures emerge from the focus on the relationship between emergency (or the exception) and legal order itself. Constitutional law scholars engage with these challenges through debates over constitutional design. For scholars of disaster law, these challenges flow from their identification of the predictable ways in which law and policy fail to prevent and ameliorate disaster vulnerability and their pathways for reform. Relying on the detailed work of Loevy, this part highlights how each of these bodies of scholarship rests on different sets of assumptions about emergencies. Bringing this literature together presents a complex picture of how emergencies are governed by public law.

3.1. The Definitional Challenge

All three bodies of scholarship engage with the definitional challenge of what constitutes an emergency. In legal theory, the work of Nazi legal theorist, Carl Schmitt, looms large.Footnote 33 For Schmitt, the exception (the extreme emergency which threatens the state) is unpredictable and can neither be anticipated nor completely defined in advance.Footnote 34 The declaration of the state of exception and its response, he argues, are purely political determinations – made by and revealing of sovereign power. As Loevy observes, this quality of ‘indefinability’ is presumed in much of the legal theory and constitutional law scholarship. As a result, this literature is ‘either too focused on an excessively limited set of conditions [the liminal case] or, more often, too invested in institutional design that will confront all possible exigencies’.Footnote 35 For instance, scholars debate whether emergency powers should be understood as ‘inside or outside’ the constitutional order.Footnote 36

In contrast to the indefinable emergency, disaster literature offers numerous definitions of the emergency, often focusing on the definitional contours between emergency, disaster, crisis, etc.Footnote 37 In disaster law literature, the emergency is very much definable – and also observable and often predictable. Hurricanes, fires, floods, and earthquakes all occur with regularity. Emerging literature on climate disasters and the law confronts the issue of predictability. Scholars note, on the one hand, that climate change has amplified the threat of extreme events such that ‘[d]isasters are becoming the new normal’.Footnote 38 At the same time, they observe that we can no longer ‘rely on historical data to assess future risks’, and that we must prepare for clustering and cascading disasters, for which we have little precedent.Footnote 39

Bringing together some of these background assumptions, Loevy shows how the definitional challenge materializes in law. Her close examination of the prominent post-9/11 decision of the UK House of Lords in Belmarsh Footnote 40 shows how, on the one hand, the Court insists that the declaration of an emergency was indefinable – a political decision that the Court could not review. Still, the record before the Court, and indeed the Court's own reasons, were crowded with potential definitions for the alleged emergency. These potential definitions drew on standardized sources (legal precedent, the parties’ evidence) and precise attention to who or what was threatened and how. The definitional challenge – and conflicting responses to this challenge – are embedded in law. As Loevy's interpretation of Belmarsh shows, these conflicts can reside in a single decision to significant legal effect.

3.2. The Temporal Challenge

Legal theory, constitutional law and disaster law each address the role of time in regulating the emergency. In legal theory and constitutional law scholarship, time plays a ‘double role’ of urgency and temporariness.Footnote 41 Loevy describes this as the assumption of ‘exceptional time: because emergencies require immediate response, emergency powers enable exceptional measures to be exercised for an exceptional, limited period of time’.Footnote 42 The worry, then, is the normalization of exceptional emergency powers as permanent features of constitutional order. Indeed, many argue that this is already the case.Footnote 43 Agamben argues that the emergency threat is not the suspension of legal order in its entirety, as Schmitt's theory suggests, but rather the pockets of exceptional power embedded throughout the legal system.Footnote 44 This produces ‘zones of indifference’, not inside or outside legal order but suspended in between, which deprive individuals of the full protection of the law.Footnote 45 For Agamben and others, the emergency reveals the failure of liberal legal order both in theory and in practice.Footnote 46

The observation that emergency powers are permanent – not temporary – jibes with disaster law scholarship. This literature emphasizes ongoing regulation through a cycle of disaster management, not simply the declaration of emergency.Footnote 47 In this way emergency measures are normalized: public institutions should always be at some stage of regulating the emergency, be it prevention, preparedness, response or recovery. Moreover, principles such as ‘disaster risk reduction’ make clear that it is not just specialized government departments that should be engaged in this cycle, but rather all institutional decision making must implement disaster risk reduction.Footnote 48 On this view, managing emergencies ought to be built into the very machinery of government.

Loevy's work demonstrates how these layers of time play out in the real-world regulation of emergencies. By examining the archetypal question of the legality of torture in the face of the ‘ticking time bomb’, Loevy convincingly refutes the conventional assumption that this is a situation governed by ‘exceptional time’. Through close analysis of the prominent 1999 torture decision of the Israeli Supreme Court,Footnote 49 Loevy unpacks the multiple timescales in the decision. This includes, for instance, the notion of ongoing and circular time relied on by intelligence officials (and emergency management staff generally)Footnote 50 to anticipate, prepare, respond to, and recover from threats. She observes that multiple legal timescales factor into the decision: for instance, the expedited court proceedings, and the possibility of ex post criminal liability.Footnote 51 Pushing beyond the assumptions of urgency or the temporary/permanent binary, her attention to context reveals multiple timescales – some exceptional, but others structural and ongoing – all of which govern the emergency.

3.3. The Exceptionality Challenge

Finally, these three fields of research address questions of whether and how to authorize exceptional emergency response measures and how to hold accountable the exercise of such powers. While many scholars doubt the resort to exceptional powers in specific cases,Footnote 52 few doubt that in some instances exceptional measures will be necessary to respond to an extreme threat.Footnote 53 Exceptional emergency powers raise worries shared across the literature: consolidating power in the executive branch, unfettered discretion, undermining individual rights and freedoms (especially of vulnerable populations), and eroding administrative law protection of transparency, participation and access to the courts.Footnote 54 Legal theory, constitutional law and disaster each address whether and how these powers can be authorized and held to account.

In legal and constitutional theory, emergencies are often tied to notions of ‘sovereign control’.Footnote 55 For Schmitt, and legal theorists who follow his thinking, both the state of exception and its response are declared by the sovereign (the modern-day executive) and, conversely, the exception reveals who is, in fact, the sovereign.Footnote 56 In this view, the executive is activated and wields power that is unconstrained by law. Legal theorists and constitutional scholars thus focus on questions of constitutional design, which acknowledge the need for emergency response but still contain the exercise of these exceptional powers. For instance, some argue in favour of derogation models, as represented by Article 15 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms,Footnote 57 which is said to create a ‘double-layered constitutional system: both layers exist within a regime of legality but only one exists within the human rights regime’.Footnote 58 Others note the prevalence of a legislative model in which emergency management legislation delegates specific emergency response powers to the executive branch.Footnote 59 Both constitutional and legislative models acknowledge the necessity for exceptional measures, but seek to subject these measures to some legal constraints to ensure the preservation of legal order.

Disaster law, too, urges law reform that anticipates the emergency and the appropriate response. Contemporary paradigms for disaster management – namely risk, vulnerability and resilience – all ‘decentre’ emergency response. Instead, they emphasize preparedness and continuous learning, which take place through ordinary and familiar practices of legislation, regulation, and planning.Footnote 60 Disaster law researchers identify the predictable ways in which emergency response fails and, accordingly, they identify the best practices that address these forms of mismanagement.Footnote 61 Emergency management legislation, which identifies roles and responsibilities, is a must.Footnote 62 Dedicated emergency management legislation that explicitly links to other legal regimes to reduce vulnerability to disaster is even better.Footnote 63 Scholars argue that legislation must require or facilitate adaptive and resilient practice, such as through robust emergency planning.Footnote 64 They highlight the role of legislation in addressing predictable failures by countering disaster myths, setting out guiding principles, and making tough choices in advance.Footnote 65 In this literature it is very much the law of the ‘ordinary’ that is – or should be – the dominant mode of governing the emergency.

In contrast to legal and constitutional theory, disaster law literature does not presume a unified and activated executive responding to a threat. Growing out of major disasters, such as Hurricane Katrina, disaster law scholarship identifies the ‘jurisdictional problems’Footnote 66 that often characterize emergencies. Indeed, recent emergencies such as wildfires and the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted numerous high-stakes jurisdictional problems around the world.Footnote 67 In these moments of emergency response, different jurisdictions (national, subnational, Indigenous) jostle for control – or redirect blame elsewhere – as they engage other jurisdictions to mount a response. Moreover, the influence of ‘resilience thinking’ on disaster scholarship means that all sectors of society (community members, businesses, international organizations, and so on) should be enlisted in disaster management. Catch phrases of ‘whole community’ and ‘all-purpose means’ capture the capacious concept of disaster resilience, which aims to have as much of the affected population as possible able to help themselves and each other, thereby freeing up government support for the most vulnerable.Footnote 68 In contrast to the image of centralized emergency powers portrayed in legal theory and constitutional literature, disaster law literature emphasizes de facto decentralization through the mobilization of all of society in disaster risk reduction.

Holding accountable the exercise of emergency powers is a major theme across the literature. Much legal theory and constitutional scholarship focuses on the relatively weak role that courts historically have played in constraining the exercise of emergency powers. This leads some to argue for an understanding of the emergency response that is ‘extra-legal’ and subject only to political, and not judicial, oversight.Footnote 69 Others argue for more robust judicial review of emergency powers,Footnote 70 or for creative institutional design.Footnote 71 Picking up on the possibility of creative institutional design, and on the complicated jurisdictional problems documented in disaster law literature, Loevy argues that accountability can be understood only by a close analysis of real-world institutional dynamics. She argues that institutional competence and culture always contain constraints, even if conventional and formal legal controls appear weak.Footnote 72 She observes, as examples, the influence of public institutions such as the UK Joint Commission on Human Rights and the US Office of Legal Counsel in the exercise of counter-terrorism measures. She finds that the specific institutional cultures and competencies of those actors involved in emergency response explain how power is constrained.

Legal theory, constitutional law and disaster law scholarship contain varied assumptions about emergencies: how they are defined, regulated by time, authorized and held to account. Sometimes these assumptions operate in parallel, but often the literature presents intersecting and divergent characterizations of emergencies and their governance in law. As shown above, discordant assumptions appear in specific legal decisions, sometimes with significant legal effect. Climate emergency declarations reflect back this complexity through manifold definitions, diverse temporal narratives, and tensions between authorization and accountability.

4. THE PARADOXES OF CLIMATE EMERGENCY DECLARATIONS

This part turns to climate emergency declarations themselves. While not conventional declarations of emergency, these declarations engage with the same three sets of perennial concerns about emergencies in public law. Furthermore, the ways in which these challenges of definition, time and exceptionality are addressed in climate emergency declarations reveal multiple paradoxes in emergencies and emergency powers.

4.1. Definitional Paradoxes

City Council declare[s] a climate emergency for the purpose of

naming, framing, and deepening our commitment to protecting our

economy, our ecosystems and our community from climate change.

City Council Toronto, ON (Canada) Footnote 73

What precisely is the climate emergency? Two definitional paradoxes emerge from the texts of these declarations and their justifications. Firstly, the declarations call upon the known and the unknowable elements of emergencies. Secondly, the declarations narrow the problem of climate change to an acute crisis while simultaneously addressing the systemic nature of the problem.

Many climate emergency declarations tap into the sense that emergencies are fundamentally unknowable. In Quebec (Canada), the threat is ‘“abrupt and irreversible climate change” threatening life and civilization as we know it’.Footnote 74 In the UK, ‘we are talking about nothing less than the irreversible destruction of the environment’.Footnote 75 South Australia, too, describes the emergency as the destruction of vital ecosystems.Footnote 76 The Senedd/Wales (UK) Legislative Assembly declaration anticipates that the climate emergency ‘will wreak havoc upon the livelihoods of countless people across the world’.Footnote 77 The emergency is presented as looming, dramatic, and ill-defined.

At the same time, these declarations tie the definition of the ‘climate emergency’ to known threats, conventional emergencies, and often recent experiences of record-breaking extreme events. The City of Sydney (Australia) states that ‘it is not just their frequency which is alarming – [heat waves] start earlier, become hotter, and last longer’.Footnote 78 In Vancouver, BC (Canada), the experiences of the 2017 and 2018 wildfires in British Columbia and neighbouring California (US) provide evidence of the climate emergency.Footnote 79 These declarations then extrapolate from these known events. In Yukon (Canada), South Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand, declaration sponsors identify the underlying purpose of emergency measures: to protect lives and communities from acute threats, and extrapolate to climate change. Climate change, one sponsor observes, poses the same kind of threat but on a ‘much grander scale’.Footnote 80

Most jurisdictions rely on scientific projections of climate impacts and, in particular, the 2018 IPCC Special ReportFootnote 81 to justify their emergency declarations and render the emergency ‘knowable’.Footnote 82 The scientific consensus on climate change and its impacts is a vital and necessary part of these debates. In the UK, for instance, the sponsor of the motion stated that ‘[t]he science tells us this is an emergency’.Footnote 83 We can see, in these rationales, attempts to render emergency declarations knowable – but also apolitical – by invoking the ‘exonerating discourses’ of scientific and rational assessment of the problem.Footnote 84

We see in these declarations what Wainwright and Mann call ‘two rhythms … not synchronized … There is, on one hand, the almost imperceptible background noise of rising seas and upward ticking of food prices, punctuated, on the other hand, by the occasional pounding of stochastic events’.Footnote 85 The climate emergency is a threat known and experienced, felt acutely in those stochastic events of deadly wildfires, floods, and heatwaves. However, the emergency is also presented as unknown: the background noise building to the worst that is still to come. The chaotic agent of the emergency is ever-present, the looming backdrop to contemporary life.

These declarations define the threat of climate change both narrowly and broadly by delineating its acute and systemic dimensions. A narrow and specific definition of emergency is necessary to mobilize an emergency response – to prioritize and coordinate action around a central purpose. Climate emergency declarations narrow the framing of the global and all-encompassing phenomenon of climate change by focusing on specific local impacts and the immediate core challenge of GHG emissions reductions.Footnote 86 As one legislator said, ‘[t]he new currency of the ACT [Australian Capital Territory] needs to be emissions and climate change. That is what we must value’.Footnote 87 As discussed below, these declarations commit specifically to emissions reduction targets and measures.

At the same time, the global and systemic nature of the climate challenge is not lost in the climate emergency debates and resulting measures. Many jurisdictions reference climate impacts felt elsewhere in the world and the responsibility to act to ameliorate those impacts.Footnote 88 The Aotearoa/New Zealand declaration (one of the latest declarations in this set) references ‘the over 1,800 jurisdictions in 32 countries’ which have already declared a climate emergency as support for its declaration.Footnote 89 The Quebec National Assembly supports its declaration almost entirely on the basis that other jurisdictions have acted, citing the United Nations (UN) Security Council and the fact that emergency declarations have been issued by ‘395 municipalities, ten universities and nearly a hundred civil society organizations’ in the province.Footnote 90 Each of the declarations of Vancouver, London and Sydney expresses solidarity with local governments worldwide that have also declared a climate emergency.

Several jurisdictions have widened the emergency frame to capture systemic and interrelated challenges by coupling the threat of climate change with species extinction. In Aotearoa/New Zealand, the climate emergency declaration also ‘recognise[s] the alarming trend in species decline and global biodiversity crisis’.Footnote 91 Melbourne has declared that both climate change and ‘mass species extinction … should be treated as an emergency’.Footnote 92 The unique ecologies of these two countries might explain the explicit reference to species extinction. However, the UK Parliament and Northern Ireland Legislative Assembly also recognize species decline as part of the climate emergency. This repeated linking of climate change and mass extinction is an important reminder that climate change ‘is part of a family of interlocking problems … all planetary in scope and all speaking to the fact of an overall ecological overshoot on the part of humanity’.Footnote 93 Moreover, the finality of species loss is a tangible reminder of the existential nature of the climate threat.Footnote 94

Many jurisdictions identify the particular communities that are made more vulnerable by climate change and, in so doing, hint at entangled systemic issues such as colonialism, racism and economic inequality. For example, Canada's declaration notes the heightened impacts on coastal, northern, and Indigenous communities. Sydney connects the climate crisis with ongoing colonization, through the continued approval of coal mines which undermine the ‘sovereignty and self-determination of First Australians’.Footnote 95 Economic inequality features across the declarations, noting the vulnerability of those in poverty to both climate impacts and climate transition. Sydney identifies ‘the poorest amongst us – the vulnerable, the marginalized and those that live in remote communities’ as susceptible to climate change.Footnote 96 Government inaction on climate mitigation, Sydney's declaration notes, has had significant social impacts: ‘Thousands face unemployment, denied potential jobs in a burgeoning renewable energy sector’.Footnote 97 Yukon, too, notes the social vulnerability of being a northern territory and the associated challenges of transitioning from fossil fuels.Footnote 98 Finally, in many jurisdictions climate emergency declarations have since become linked with recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, with some jurisdictions translating lessons learned in the pandemic to climate change.Footnote 99

This tension between the acute and systemic is eloquently captured in the debates leading to the unanimous declaration in Yukon, a northern Canadian territory:

We are seeing wildlife and plant species claim habitat in places they haven't been before. Water systems are changing course or drying up. They are low or taking new paths as glacial sources retreat. Species like the pine beetle are threatening to make their way to Yukon's forests. Wildfires are becoming more frequent and intense. Buildings and highways are needing more and more expensive repairs due to the permafrost thawing under them. These changes and more are affecting the way that we do business, our economy, the way we interact with the land, and our cultures. There's no doubt we are in the midst of a climate crisis.Footnote 100

The environment, the community, the economy, and a way of life are all threatened by the climate emergency. Yet, these are not generic statements or ‘imperceptible background noise’. In the north, the climate emergency is specific and tangible: ‘You [can] smell the soil in the air because of the permafrost melting’.Footnote 101

Climate emergency declarations provide layers of definitions for the emergency. I have identified two paradoxes embedded in these layered definitions. Firstly, the climate emergency is known and unknown. It is felt through the lived experiences of many communities which now live ‘under’ a declared climate emergency. Common sets of experiences, concerns and sources – such as the IPCC Special Report – provide the basis for defining the emergency. At the same time, these declarations call upon the unknowable looming future, which is ‘worse, much worse, than you think’,Footnote 102 to justify declaring a climate emergency. This framing of the extreme threat is used to engage ‘emergency mode’ to focus government attention and action on the immediate emergency of rapidly reducing GHG emissions. However, this narrow framing, too, is embedded within a web of systemic crises, such as mass extinction and systemic inequality.

4.2. Temporal Paradoxes

The IPCC has given us 12 years. In climate science,

that is a heartbeat. We have to get this right.

Richard Benyon (Member for Newbury), UK Parliament Footnote 103

As we saw in Section 2, debates about the legal regulation of emergency are bound up in notions of time. While the notion of ‘exceptional time’ – that there is no time in an emergency – is a common assumption in public law literature, emergencies are in fact regulated along multiple timescales. Climate emergency declarations eschew simple temporal narratives. Two further paradoxes emerge from a close read of the timescales portrayed in these declarations. Firstly, climate emergency declarations both compress and expand our perception of time. Secondly, the declarations treat the climate emergency as both temporary and permanent.

As the epigraph shows, Loevy's notion of exceptional time plays a prominent role in the framing of these declarations, compressing our sense of time and generating urgency.Footnote 104 The emergency takes place in ‘a heartbeat’. Most of the declarations, as seen above, emphasize the urgent need for action. This is because communities are already experiencing the disruption of a changing climate.Footnote 105 In the words of the UK Parliament, ‘[t]his is no longer about a distant future’.Footnote 106 In Quebec it is ‘too late for gradual transition’ and the time to take dramatic action is now.Footnote 107 The UK motion extolled that ‘[w]e have no time to waste’ and, in Wales, that ‘time is ticking away against us’.Footnote 108 Urgency is stressed in multiple declarations, both to reduce emissions and also to ‘capture economic opportunities and green jobs’.Footnote 109 In contrast, the Canadian declaration is critiqued by the opposition for the one-month delay in placing it on the agenda, undermining the claim that there is no time.Footnote 110

However, these declarations also expand the temporal horizon. The climate emergency in some cases is a response to the immediate past – recent record-breaking heatwaves, floods, and fires – but they stretch even further back along geologic time. The legislative debate in Yukon has repeatedly noted the remarkable increase in average temperature in the north: a 2.3°C increase between 1948 and 2016 (with a corresponding 4.3°C increase in winter temperatures).Footnote 111 One member captured the sense of geologic time by calling the climate emergency a ‘slow-moving … ever-evolving emergency’.Footnote 112 Others called the declaration ‘bittersweet’ because, while government action is finally happening, there is still so much to do.Footnote 113 In Aotearoa/New Zealand, one member spoke of the ‘time we cannot get back’ in reference to the current precarious species survival.Footnote 114 The sense that the climate emergency has now arrived thus hangs together with the much longer timescale along which human activity has brought this emergency into being.

Climate emergency declarations also contain the decidedly ‘unexceptional’ timescale of emergency management: plodding, ongoing, managerial. As discussed further below, this manifests through the combination of targets, plans and reporting obligations, all consistent with conventional and continual government tools for emergency management. Time marches steadily on through ongoing planning, interim targets, reporting requirements, and end goals.

In contrast to the quotidian, ongoing practice of emergency regulation, grander temporal narratives emerge as well. Climate emergency declarations tell constitutional stories about the past and future identity (or identities) of the community and the roles of their public institutions.Footnote 115 This constitutional narrative is perhaps the strongest in the UK debates in which multiple members noted the country's responsibility to act on climate change:

This is the mother of all Parliaments. This is the country that had the first industrial revolution. It is our moral responsibility to come together as a Parliament and show the leadership that people across the world rightly expect of us.Footnote 116

The distant past – the industrial revolution – offers a source of inspiration for the coming ‘green industrial revolution’.Footnote 117 The debates also draw on the nation's responses to the World Wars to galvanize support for efforts to address the climate emergency. While the constitutional narrative in the UK is one of national unity, legislative debates in Canada, Scotland, Northern Ireland and Aotearoa/New Zealand failed to generate the same response.

The constitutional narrative is also projected into the future by imagining how this moment of either action or inaction will be looked back upon. National governments express their sense of obligation to young people and future generations. In Aotearoa/New Zealand, this obligation also flows from Māori law:

We have an obligation to our rangatahi [young people] to unite and to do everything as kaitaki [leaders] to protect our taiao [world] and our whānau [future generations] from the climate crisis in the short time we have left.Footnote 118

This connection between the urgent now and the far-off future flips on its head the conventional worries about the permanent emergency in legal scholarship. The moral (or perhaps even constitutional) obligation to act now, as discussed here, is what is needed to ensure that a state of climate emergency does not become permanent.

These varied and criss-crossing timelines complicate the assumption that emergencies are temporary events. In some ways the contemplated response is very much ordinary law and governance with no clear end point for measures such as new building code regulations or carbon-pricing schemes. However, the year 2050 also looms as a precipice.Footnote 119 The future beyond 2050 is an open question. Is it permanent climate emergency, as the Quebec Citizens’ Universal Declaration describes (‘economic collapse, public health crises, worldwide food shortage, annihilation of biodiversity, and national and international security crises of unprecedented scope’)Footnote 120 or is it restoration of some pre-2005 or pre-1990 status quo ante?Footnote 121

These declarations of climate emergency thus reveal another temporal paradox, a tension between preservation and transformation. If the climate emergency is temporary, then the objective of the declaration is to preserve some notion of pre-emergency normality; but the climate emergency may have long-lasting transformative potential to bring about some different future. Much contained in these declarations focuses on preventing the worst of anticipated climate impacts in order to stabilize a version of the status quo. For instance, most implementation documents prominently feature support for electrification of transportation, such as investment in and incentives for electric vehicles.Footnote 122 Some jurisdictions are explicit about intentions to rely on carbon capture technology or offset measures, which may not yet (or ever be) feasible.Footnote 123 Many are enthusiastic about new opportunities for developing biofuels, hydrogen technology, and generally the renewable energy economy.Footnote 124 The UK Citizens’ Assembly report also echoes this desire to preserve the status quo in its recommendations to minimize restrictions on travel and lifestyles, and to balance the freedom to fly with net-zero targets.Footnote 125 On this view, the climate emergency is something temporary, exceptional – and avoidable – by taking steps to adjust current practices, but without disrupting the status quo.

At the same time, however, many of these declarations contemplate transformation. Vancouver's climate declaration is framed around justice and equality, commitments implemented through a Climate Justice Charter and partnership with Indigenous peoples.Footnote 126 While the Scottish government has expressed its keen interest in carbon capture technology that reinforces the status quo, the Scottish Just Transition Commission and Citizens’ Assembly have called on the government to undertake transformative change by, for instance, centring government decision-making frameworks on the concept of well-being rather than gross domestic product.Footnote 127

The Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland response to the climate emergency also outlines a transformative vision which, incorporating Māori law, calls for ‘a change in our response to climate change, re-framing, re-imagining and re-setting the current system, and a shift from a human-centred approach to an ecological-centred approach given our symbiotic relationships with the natural environment’.Footnote 128

With Māori knowledge integrated throughout, the plan outlines a broad set of goals: not simply rapid emissions reduction, but also ‘social, environmental, economic and cultural wellbeing’.Footnote 129 The plan incorporates Māori-led ‘transformational priority pathways’, including regeneration of ecological systems and shifting to a regenerative economy, backed by specific actions.Footnote 130 While many specific items of the plan's 26 sub-actions track those in other jurisdictions, the Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland framing of the climate emergency explicitly embraces permanent and transformational change.

From the perspective of the official opposition in the New Zealand House of Representatives, the anticipated climate transformation does not bend in the direction of justice. Speaking against the motion, one member described the climate emergency as:

[a licence to] tell you what car you can drive, what days you can drive, the size of your house, how much energy you can use and where you buy it from, and how many flights you can take. … Success means not having the climate change Minister telling us how to live our lives to cut emissions – because that means failure in every sense.Footnote 131

On this view, the climate emergency is being used as a cover to avoid scrutiny of a transformative government agenda, engaging the enduring scepticism of legal scholars that emergency powers can ever be temporary. We can see how conflicting characterizations of time are embedded in these declarations. In some ways, they seem to invoke conventional emergency framing, which demands temporary departure from the rule of law to preserve the status quo ante. In other ways, they reflect an expression of the urgent need to depart from the status quo to better realize rule-of-law aspirations in a changing environment. If the latter is the case, then perhaps the ‘emergency’ frame is too limited to describe the full potential of these declarations.

A close read of these declarations shows that multi-layered temporal horizons characterize the climate emergency. These declarations both compress and extend our perception of time, and challenge assumptions about the temporary nature of emergency measures. By declaring an emergency, these statements present a picture of ‘an on-rushing future that severs the present from the past and compresses the time for decision and action’.Footnote 132 As stated in the Yukon Legislature and Senedd, the declaration must be treated as a new beginning.Footnote 133 At the same time, however, these declarations call on both distant pasts and futures as sources of obligation and action. They also grapple with competing objectives of preserving the status quo – by treating the climate emergency as temporary and exceptional – versus the transformative possibilities of emergency governance. Just as climate change plays out on multiple time scales, so too do these declarations.

4.3. Exceptionality Paradoxes

The motion before us employs all the implied drama of the

word ‘emergency’, but it does so with zero practical effect.

Nicola Willis, New Zealand House of Representatives Footnote 134

This section considers who responds to the climate emergency and how. As we saw above, questions about emergency response focus on anxieties about authority (who gets to decide and what exceptional powers they have) and accountability (how to prevent and correct executive overreach). Climate emergency declarations contain paradoxes of authority and accountability. Their implementation is characterized by both the ordinary and exceptional: familiar practices and new instruments. Moreover, implementation is characterized by unilateral action and jurisdictional challenges: consolidation and creative institutional design.

Responses to the climate emergency contemplate both familiar measures and institutional creativity. One view of climate emergency declarations, captured in the epigraph, is that they do nothing: they do not authorize anything new and certainly not the kind of exceptional powers typically associated with emergencies.Footnote 135 Indeed, the bulk of these climate emergency declarations operate through ordinary government functions of planning, setting targets, and reporting. Thus far, implementation of these plans has not led jurisdictions to invoke exceptional measures.Footnote 136 Rather, they have relied on investment, non-binding policies, education, advocacy and the ordinary legislative process (for example, bills to legislate GHG reduction targets and new city by-laws).Footnote 137

This reliance on decidedly ordinary governmental powers lends some support to the view expressed in the epigraph that climate emergency declarations have no emergency ‘substance’. So, too, does the fact that a number of jurisdictions have undertaken subsequent climate measures that make no reference to their declaration of climate emergency.Footnote 138 In most cases, jurisdictions have not issued separate plans or measures to respond to the climate emergency declaration.Footnote 139 Rather, many incorporate references to the climate emergency declaration into plans and actions already under way. From a strictly causal perspective, it is thus difficult to discern what, if any, difference the declaration of climate emergency has made to a ‘business as usual’, which, in some jurisdictions, already contemplated considerable emissions reductions.Footnote 140

Recall, though, that disaster law literature emphasizes the predictable and ongoing regulation of emergency management. From this perspective, climate emergency declarations are operating as they should. With contemporary disaster research emphasizing resilience, the regulatory emphasis shifts from response to preparedness and risk reduction. A key feature of emergency preparedness is an emergency plan which identifies vulnerabilities, priorities, roles, and responsibilities. Relatedly, disaster risk reduction requires all institutions of government to operate in concert to mitigate disaster risk outside acute emergency response. The declaration of emergency by the Scottish Climate Change Secretary captures these insights, stating that ‘[a]n emergency needs a systematic response that is appropriate to the scale of the challenge and not just a knee-jerk, piecemeal reaction’.Footnote 141 Many of the climate implementation plans issued by these jurisdictions provide a systematic response, which engages multiple sectors of society. A number of these plans specifically require a ‘whole of government response’, including applying a ‘climate lens’ to all government decision making.Footnote 142

At the same time, climate emergency declarations engage the energetic nature of emergency powers. Most jurisdictions emphasize the urgency of emissions reduction and many set out an expedited or accelerated schedule for specific actions. The Climate Change Strategy for ACT illustrates the rapidity of anticipated reductions under its plan: its 2030 projection for emissions reduction with additional measures is 8.5 times that of reductions for business as usual.Footnote 143 After the First Minister's declaration (which stated if ‘we can go further or faster, we will do so’), Scotland did indeed update its proposed Climate Change Bill amendments to a 2045 target, rather the original 2050 date.Footnote 144

New instruments are also proposed or implemented through the emergency declaration. For instance, Vancouver's climate emergency declaration requires the development and implementation of a carbon budget for the city, based on its proportion of emissions in a 1.5°C warming scenario. London and Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland have explicitly based their current plans on detailed carbon budgets.Footnote 145 One goal of the Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland plan is to ensure that all decision making does not exceed its carbon budget, an enduring commitment even through the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 146 A further example of creativity is Sydney's call to create a federal Just Transition Authority, an independent commission with a mandate to transition workers in the fossil-fuel industry into alternate, suitable employment. While the Australian government has not responded, Scotland has implemented a similar innovation. The Scottish Just Transition Commission, an independent commission, has issued wide-ranging recommendations to the government on how to give effect to a just and fair transition.Footnote 147 Some of these recommendations include new tools for land-use planning and a reformed legal framework for land ownership.Footnote 148

Related to this paradox is a second. Climate emergency declarations address the need for unilateral action while also embracing society-wide mobilization and partnership. Conventional emergencies evoke concerns about the concentration of power in the executive because emergencies present an opportunity for a power grab, with only weak mechanisms for accountability. Indeed, it is this notion of the activated executive which appeals to climate activists, who draw on wartime analogies for framing the response to climate change.

Some activation and consolidation can be observed in the declarations. In Aotearoa/New Zealand, the urgency and priority of the climate emergency is signalled by leadership at the very top: a climate response ministerial group, chaired by the Prime Minister.Footnote 149 Scotland's Just Transition Commission calls for the Deputy First Minister to be responsible for the just transition to zero emissions.Footnote 150 Similarly, the City of Toronto's declaration is a long list of directives issued to city staff. New cabinet committees and lists of new tasks and measures to be undertaken by a largely out-of-sight bureaucracy raise concerns about the use of emergency powers: that is, they expand executive powers and undermine public participation and transparency through a rapid and technical response.Footnote 151 The centrality of emissions modelling and accounting in many of these plans may raise similar concerns – that emergency response is moved into the realm of the technical, thereby limiting democratic engagement and political creativity.Footnote 152 While perhaps an unintentional mix-up, the exclusion of climate activists from the Senedd during the climate emergency declaration debate triggered wider concerns about emergency powers.Footnote 153

However, this appears to be only part of the story. Implementation post-declaration, in many jurisdictions, has emphasized society-wide mobilization and partnership in both process and outcome. For instance, a cornerstone of both the UK and Scottish implementation has been Citizens’ Assemblies, in which representative groups of roughly 100 citizens deliberated on how to address the climate emergency.Footnote 154 Citizens’ Assemblies provide a process through which to engage citizens directly in policy development for responding to the declared climate emergency. The plan issued by Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland features partnership and cooperation as framing devices and method.Footnote 155 The plan was developed with guidance from the Mana Whenua Kaitiaki Forum, a governance body of Māori authorities; it was co-drafted with rangatahi (Māori youth); and it specifically outlines which parts of implementation are the responsibility of Auckland Council, central government, mana whenua, local boards, businesses, individuals and communities, young people and rangatahi Māori, civil society, research institutions and academia, and C40 Cities.Footnote 156

Beyond this broad engagement, some jurisdictions have designed institutions to make climate emergency response accountable to those most vulnerable to climate change. For instance, Yukon has constituted a Youth Panel, which advises the government on its 2030 Climate Plan.Footnote 157 Vancouver has a Climate and Equity Working Group, which reviews all actions on climate emergency response and has had a notable impact on the policies announced thus far.Footnote 158 In Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland, the Independent Māori Statutory Board and the Mana Whenua Kaitiaki Forum are both involved in the implementation of the city's climate plan.Footnote 159 In addition, Yukon, Vancouver, Sydney, and Aotearoa/New Zealand all contemplate implementing climate actions in partnership with Indigenous peoples. Further institutional reform in the UK and Northern Ireland contemplates new enforcement tools to ensure compliance with climate measures.Footnote 160

What is clear is that, across these declarations, climate emergency response is unfolding through complex, multi-level institutional dynamics. These intricate institutional relationships pose questions about accountability and coordination, which require further analysis in the light of each jurisdiction's legal culture and institutional norms. At a broad level, however, it is worth observing that climate emergency declarations, in many instances, are provoking institutional innovation as a form of accountability.

This institutional creativity cuts against the assumption that an emergency activates a centralized, unified executive. Climate emergency declarations reveal a suite of ‘jurisdictional problems’,Footnote 161 through coordination challenges with other governments and calls to mobilize society broadly. These jurisdictional problems are nicely illustrated by Sydney's climate emergency declaration, which identifies climate impacts on the people of Sydney but then declares that climate change ‘should be treated as a national emergency’.Footnote 162 Similarly, the Scottish government declared a ‘global climate emergency’.Footnote 163 Australian municipal and territorial governments capture coordination challenges when they place the blame squarely on the conduct and inaction of the federal government. Subnational governments in the UK, too, note the constraints they face from an unresponsive central government.Footnote 164

Cities have played a leading role with climate emergency declarations and responses, as local governments continue to find new and innovative ways to advance climate action in the face of limited resources and power.Footnote 165 Municipal climate emergency responses feature specific measures to engage higher levels of government. Developing ‘a lobbying strategy for a range of new and existing asks from central government’ is identified as a key priority under London's climate emergency declaration.Footnote 166 Vancouver also notes a pandemic-induced shift from investment to regulation and advocacy.Footnote 167 Partnership and coordination with other cities is another theme, emblematic of both the necessity for and challenge of multi-level governance in emergency response.

Climate emergency declarations illustrate the challenge of needing to act unilaterally in response to threats to life, livelihood and property, while also facing jurisdictional and coordination complexity. Indeed, much of the most tangible climate emergency response action is taking place at the local scale. What makes the unilateral action remarkable is that most of these jurisdictions are municipalities; the relative contribution of each to global GHG emissions is tiny, yet they forge ahead with some of the most specific and ambitious climate emergency actions. Like other systemic social issues, ‘[a]lthough federal and provincial governments have helped to create this … crisis, it is largely the cities that are left to solve the problem’.Footnote 168 Vancouver, London, Sydney and Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland all seek greater support from central governments, but they do not wait for this.Footnote 169 Rather, their declarations all express the hope that they will be in a stronger position to make these requests of other jurisdictions – and, indeed, broader society – if local governments themselves show leadership.

The need for rapid, exceptional and coordinated action animates these climate emergency declarations and engages similar questions of authority and accountability that occupy public law scholars. Climate emergency declarations and their implementation thus far reveal routine governance practices as well as institutional invigoration through actual and proposed novel measures (carbon budgets) and executive bodies (Cabinet Committee, Just Transition Commission). While these new features raise familiar concerns about undermining democratic norms and consolidating power, much ongoing implementation has nonetheless featured partnership and society-wide mobilization. Climate emergency declarations contain a rich dialogue about the regulation of emergencies as the exception and, in fact, highlight the varied modes of governance that are being brought to bear on the climate challenge.

5. CONCLUSION

Climate emergency declarations spotlight ongoing public law debates over how emergencies are governed by law. The legally ambiguous nature of these declarations concentrate disparate and contested assumptions about emergencies. Through an analysis of a subset of climate emergency declarations, this article has argued that these declarations engage the perennial worries of public law scholars about emergencies: the difficulty of definition, the necessary but shifting role of time, and the issues of authority and accountability that flow from resort to emergency powers. It has shown that along each of these dimensions, climate emergency declarations are filled with paradoxes. The climate emergency is at once known and unknown, acute and systemic, immediate and expansive, temporary and transformative, routine and exceptional, centralizing and decentralizing.

These paradoxes have legal significance because they are rooted in ongoing debates over the governance of emergencies in law. The proliferation of climate emergency declarations around the world has shifted climate discourse to emphasize the need for wide-scale, coordinated action to protect communities from worst-case scenarios. However, as discussed above, the emergency frame does not circumvent difficult legal and policy dilemmas. Instead, climate emergency declarations shift the terrain to new debates over how to govern through crisis. Emergencies are always complex political, legal and regulatory phenomena characterized by multiple paradigms. Climate emergency declarations provide a snapshot of these debates; they condense and crystallize the many paradoxes of emergencies in public law; they allow us to see the dialogic nature of ‘the emergency’ as it plays out on this new terrain of climate disruption.

Public law scholars have described climate change as a ‘legally disruptive phenomenon’ because climate change forces legal concepts, doctrines, and assumptions to evolve beyond incremental application.Footnote 170 Climate emergency declarations are one site of legal disruption. Emergencies are unstable moments without a fixed image of the future.Footnote 171 Climate emergency declarations reflect back to us this instability in the form of public law paradoxes, highlighting that, in a climate-disrupted world, the future is very much up for debate.