Introduction

Beginning in the nineteenth century, the teaching profession changed drastically. In many countries across the Western world, it went from being primarily a profession for men to one increasingly for women. In England and Wales, 60 percent of the elementary teachers were women as early as 1877, in Belgium the corresponding share of female primary school teachers was 49 percent in 1896, and in Russia about 70–75 percent at the turn of the century. By 1900, these figures were 68 percent in Italy, about 75 percent in the USA, and 66 percent in Sweden.Footnote 1

Although further studies are certainly required, this development has received a healthy dose of attention from educational researchers. We have gained many insights into areas such as the historical conditions of this process as well as the socialization and working conditions of female teachers, their salaries, levels of professional status, and strategies.Footnote 2 In this article, we examine the results of the feminization of teaching, exploring the work and living conditions of female primary school teachers with a focus on their experiences of loneliness, harassment, and violence in early twentieth-century Sweden. Specifically, we ask: What were the perceived risks of and threats toward females that were debated during this period? How were these risks discussed, and by whom? What solutions were presented, and what actions were taken?

By answering these questions, we contribute to research on the living and working conditions of female teachers and their social position in rural areas. As this article shows, there were more to the inequalities that faced female teachers than merely their comparatively low wages. Here, we argue that the debate identified two main problems: the isolation of female teachers, and the threat that men posed. In addition to the gender gap in wages, we argue that there was a gender gap in an emotional sense, indicated by the female teachers’ experiences of vulnerability and loneliness. While female teachers in the early twentieth century were not the first of their profession to experience such emotions, their situation now became a matter for public debate among politicians (males) as well as (primarily female) authors and teachers. As a result, a wide range of solutions to these problems was presented, including providing female teachers with weapons for self defense, and telephones or tenants to reduce their isolation. By exploring these proposed solutions, we can show that the professional struggles of early twentieth-century female teachers not only included a fight for wages and status, but also for mental and physical security. By shedding light on the risks for female teachers in rural areas, and how their contemporaries addressed this issue, this article also provides a historical context to our current discussion on the vulnerability of teachers.

Professionalization, Gendered Violence, and Emotions

Although the history of the teaching profession has certainly been overlooked for a long time, we now have ever-growing knowledge about the history of the professionalization and the daily work of primary school teachers.Footnote 3 A classic example that touches upon many of the topics in this literature is a seminal book by Depaepe, De Vroede, and Simon that examined the legal status, career prospects, living standards, and social characteristics of the profession.Footnote 4

As this research has shown, the status of the teaching profession has been varied and complex. Teachers have been variously described as either educated or semi-illiterate, well-paid or under-paid, and as part of the social elite or as commoners. As a result of this ambivalent attitude, teachers have often been situated somewhere at “the very edge of professional respectability,” to use the phrase of John L. Rury.Footnote 5 Studies have shown that mid-nineteenth-century French teachers had cause to complain over their lack of professional standing, describing themselves as “everyone's flunkey” and “everyone's dog to kick around.”Footnote 6 In the US, a 1902 report on rural schools in Wisconsin provides another example of teachers’ problematic position, claiming that teachers were largely “young, immature, half-trained, ineffective and lacking in professional ideals and ambitions.”Footnote 7 Studies exploring the position of teachers in Austria and Finland indicate that teachers dealt with this precarious situation in various ways. These included adapting themselves to the local communities and their social requirements, or by using what has been called “a cosmopolitan strategy,” which meant that teachers distanced themselves from the lives of common villagers.Footnote 8

Increasing attention has been paid to the position of female teachers, their salaries, social backgrounds, status, and political and professional struggles.Footnote 9 Recent studies have also examined the discursive construction of the female teachers and investigated their social networks, their relations to children and parents, and their impact on the enrollment of girls in primary schools.Footnote 10 Other studies have addressed how female teachers defended their positions through education, and organized and established associations, published journals, and took political action on national and local levels.Footnote 11 These contributions provide important insights into how teaching was professionalized, how female teachers influenced their own employment, and how this employment changed over time. A classic example of such a study is Mineke van Essen's investigation of Dutch female primary and secondary school teachers, in which she shows that these teachers employed a wide range of strategies to strengthen their positions, including attending special courses, earning school leader certificates, developing and monopolizing girls’ education, fighting for higher salaries, and struggling to abolish restrictions for female teacher employment.Footnote 12

This article makes several contributions to this research field. In addition to providing additional insights into the experiences of female teachers, we broaden our understanding of the professional strategies and struggles of this group. As evident from what follows, female teachers not only strove to defend their profession in an unequal society, but also fought for improvements in more mundane and specific issues regarding their work and living conditions. This latter issue about conditions was much less abstract and politicized than the general debate on the position of female teachers.

Additionally, this article highlights the issue of violence in the context of education and educators. As a complement to studies about teachers’ use of violence against pupils, and bullying that takes place among pupils, we will also address the issue of male violence toward female teachers, and how that violence was debated at the time.Footnote 13 The focus will be not political or religious violence, but what might be defined as everyday violence: the violence that was a part of a female teacher's everyday life.Footnote 14

Because this article covers violence against female teachers, we will address the issue of male violence. As research has shown, male violence is a global social phenomenon that has a wide range of expressions. This violence can target women, as it does in our study, and it can target both known and unknown women. In our case, it targets female teachers with whom men could have both a public and a private relationship. The violence in this article has different levels of severity, ranging from the minimal to the life-threatening, from individual incidents to persistent harassment, and from incidents experienced as non-significant to those experienced as emotionally damaging. Furthermore, the violence may be more or less sexualized, and more or less structured and organized.Footnote 15 As this article will make evident, female teachers were exposed to a wide range of male violence.

Violence toward teachers has not been the focus of individual studies, and has often been overlooked in studies of the teaching profession; there are, however, a few publications to build on. Studies of the history of the teaching profession have provided examples from Russia, Canada, England, and Ireland of teachers being abused, threatened, and physically assaulted.Footnote 16 There are also examples of humorous short films from the turn of the century, where schoolchildren set up traps that caused teachers harm in some way.Footnote 17 For female teachers specifically, there is also evidence of violence from British Columbia, Russia, and Sweden. Ben Eklof suggests that sexual assault was not infrequent in early twentieth-century Russia, and that there is evidence indicating that female teachers were hardest hit during the unrest of the 1917 revolution.Footnote 18 Evidence from British Columbia similarly demonstrates that female teachers could experience situations with male villagers that included the bothersome, the dangerous, and the outright lethal—a female teacher was murdered there in 1926.Footnote 19 The theme of vulnerable female teachers has also been covered in an analysis of the depiction of female teachers in Swedish literature.Footnote 20 While such scattered evidence suggests that violence against teachers was part of a global phenomenon, it is also a good argument for further research on this topic.

By addressing this issue of violence, this article also contributes to the emotional history of teachers and teaching.Footnote 21 While there are good reasons to believe that violence and harassment was far from an everyday experience for female teachers, the experience of violence is not only about violent acts themselves, but also about the emotions of worry, fear, exposure, and vulnerability that the potential for violence brings forth.Footnote 22 In this context, we have found Barbara Rosenwein's concept of “emotional community” useful.Footnote 23 This concept highlights how certain societal contexts or communities are marked by certain sets of feelings, and how emotions in such settings can be either encouraged, tolerated, or, as in our case, problematized. Using this concept, this article will provide insights into the emotions that female teachers experienced, recognized, and deplored. As we will show, the vulnerability of female teachers was not only a matter of fear, but also a matter of isolation. In this respect, this article is also a contribution to the historical study of emotions associated with loneliness.Footnote 24

Studying the Experiences of Female Teachers

This article examines the experiences of female teachers in rural early twentieth-century Sweden, focusing on the two categories of female primary school teachers in Sweden at the time: those who taught at a junior school (småskola), providing mainly the first years of schooling, and those who taught at an elementary school (folkskola), providing a full primary school education. In this period, it was relatively common for women to hold such positions in Sweden. In 1920, 99 percent of all junior school teachers and 48 percent of all elementary school teachers were women.Footnote 25

Exploring female teachers’ experiences of loneliness, harassment, and violence is a challenging task, since this field of research certainly suffers from the silences of history, as the experiences of subordinate groups often do. To address this dearth, we have used what has been called a “source pluralism” approach to identify the few and scattered pieces of evidence available.Footnote 26 Our investigation starts from the public debate on teachers’ conditions in newspapers and parliamentary debates from 1900 to 1940. During this period, women in Sweden gained more legal rights and more access to formerly male-dominated arenas, as the example of the teaching profession demonstrates.Footnote 27 Relevant articles and parliamentary debates were found by searching digitalized parliamentary debate and newspapers available at the National Library of Sweden, using keywords such as “teacher,” “single living,” “countryside” and so forth.Footnote 28 As a result of these searches, particular focus fell on two distinct waves of public debate, the first taking place in the 1910s and the second at the end of the 1930s.

The newspaper articles we include here vary. Some were outright political, arguing for changing policies, while other were short stories, reports of specific events, or summaries of public debates or meetings. These articles included news notices (i.e., short, non-debate items) describing local regulations or the incidents and threats toward female teachers that recurred throughout the investigated period. These articles in turn led us to other source materials, including articles published in weekly magazines, such as Swedish teachers’ magazines and women's magazines.

The Parliament debate was conducted on the basis of political proposals by members of Parliament and are thus (by nature) largely focused on potential solutions to perceived problems. These discussions were not simply for or against a proposal—they also show us how the problem itself was framed, how different arguments were valued, and what support the members of Parliament drew from real events and testimonials from female teachers. These are valuable resources for studying the contemporary discourse about the conditions of teachers and women at a time when relationships between women and men were being renegotiated, and they provide vital insights into the perceived and actual vulnerabilities of female teachers.

This diverse set of sources offers a wide variety of insights into the experiences of female teachers, including those from the perspectives of both male and female teachers, authors, journalists, and politicians. While obviously influenced by the social and political position of the writers—ranging from female teachers promoting their cause to that of male conservative party members in Parliament—the shared assumptions and conflicting views of the debate have enabled us to provide a rich analysis of the object under study. And although male perspectives are formulated in Parliament, female writers were influential in the debate because they gave voice to the experiences of female teachers. In this sense, this article also gives isolated and lonely female teachers a voice, and sheds new light on the experiences of a group of women that not only fought for better living and working conditions, but also felt the burden of being vulnerable in rural Sweden despite gaining increasing political rights during this period.

Isolation, Threats, and Loneliness

In the late nineteenth century, many of the female teachers worked and lived in isolated school buildings in rural areas. For an example of a late nineteenth-century rural schoolhouse, see Figure 1. That these rural female teachers were in a vulnerable position was well known. A study conducted in 1893 indicated that their stress levels were high: 22 percent of the teachers who were contacted suffered from anemia, weakness or neurasthenia, chronic gastritis, and so forth.Footnote 29 Newspapers also reported that female teachers suffered harassment and violence. This included the burglary of a female junior school teacher, reported by the newspaper Borås tidning in 1890. In this incident the teacher, home alone late one evening, opened her door to two strangers who threatened to kill her if she did not give them her watch and all her money.Footnote 30 Similar incidents received national coverage. The case of an assault on a female teacher in Finnåker in 1899 was reported in twenty-three newspapers between April 10 and April 18 of that year. According to the newspapers, sixteen railroad workers “hungry for kisses” (pusshungriga) visited the teacher and demanded to be kissed. Since she was defenseless, she did not dare but to give in to their wishes.Footnote 31

Figure 1. A female teacher with her pupils in front of Västansjö junior school (småskola), located in Spånäs, Hälsingland, north of Sweden. The schoolhouse was built in 1878. Photographer: Lindberg, Per/Länsmuseet Gävleborg. License: Public Domain

During the early twentieth century, the threats toward the teachers were given more serious attention, which in turn gave rise to a national political debate. Feelings of isolation and fear, which individual female teachers certainly must have felt also during the early feminization process of the teaching profession in the second half of the nineteenth century, now became publicly problematized.

An important milestone in the debate was the publication of Mathilda Roos's novel White Heather (Hvit ljung) in 1907.Footnote 32 This novel depicted a young defenseless female teacher in the countryside, and highlighted certain themes about the vulnerable position of teachers that would reappear over many years in the subsequent debate. In the national political context, White Heather did not have an immediate impact in the sense that the book did not lead to specific proposals for improvements in teachers’ living conditions. Instead, subsequent discussion revolved mainly around specific cases of individual harassment of female teachers and what responsibilities the clergy had toward them.Footnote 33 However, as a kind of starting point for the debate on teachers’ conditions, White Heather became a significant literary reference in the debate in the following decades, and was republished in 1911, 1924, and 1930.

Mathilda Roos's sister Anna Maria, also a writer, made important contributions of her own to the debate. In 1912, Anna Maria Roos published two massively influential primers for junior school that coined a term for rural bliss (sörgårdsidyll) that still remains an active part of the Swedish language in the twenty-first century. In the same year, she published an article describing a quite different rural experience entitled “A Scream of Anxiety” (Ett ångestskri) in the influential newspaper Aftonbladet. As the dramatic headline indicates, this article tells the story of an anonymous female teacher in a remote school and her terrible encounter with a male intruder.Footnote 34

Anna Maria Roos stressed the loneliness of female teachers. While loneliness often has been portrayed as a “disease of civilization” linked to modernization and industrialization, often in contrast with rural solitude, loneliness was here linked to the isolation of rural schools.Footnote 35 Roos argued that, apart from the schoolchildren that female teachers met for only a few hours six days a week, social interactions were lacking because the rural schools were so remote. This lack of neighbors and company was the key factor in the two threats posed to female teachers: the threat of home intruders and the threat of mental illness resulting from isolation. Thus isolation was one of the crucial obstacles to the well-being of the schoolmistresses, and, observed from a wider perspective, it was also an obstacle to their becoming independent working women.

Roos's suggestion for how to improve the situation of solitary teachers was based on the Swedish tradition of housing teachers in the schoolhouse. She suggested that all school buildings should have an extra apartment for rent adjacent to the teacher's apartment. Roos argued that if all schoolhouses had such apartments, “then the teacher would know that in the event of distress or danger, it is possible to call other people for help. And at the sight of a school building, the tramp (vagabonden) would no longer say to himself that here lives a lonely defenseless woman.”Footnote 36 As this proposal indicates, the vulnerability of female teachers was here seen as twofold—their isolated living situation was well known, and they themselves could not call for help if something happened to them.

Anna Maria Roos's call for action had an impact. Just a few days later, Anna Hammardahl, editor of the Lärarinnetidningen (Schoolmistress Magazine), replied. Hammardahl was critical of the proposal for apartments in school buildings, arguing that they would only be useful if they were occupied by a school cleaning woman. Otherwise, the arrangement of a stranger as tenant in the same school building would give rise to a wide range of problematic emotions: it “would almost necessarily give rise to displeasure, abrasions and discomfort of all kinds” and would not relieve female teachers from threats. Instead, threats would merely take another shape in the form of a male tenant.Footnote 37 By highlighting potential tenants as threats to the teachers, Hammardahl also provides an interesting insight into the position of female teachers in the countryside, where all men (including tenants living in the same building) were perceived as a potential danger.

Anna Maria Roos continued the debate in the following years by providing quotes from letters that she had received from female teachers who supported her proposal. In one of her examples, two female teachers who had enjoyed the company of tenants for thirty years claimed that tenants caused little discomfort, and that the few problems were “nothing compared to the advantage and sense of security that stems from human company.”Footnote 38 Thus, the testimonials highlighted by Roos emphasized human company as crucial, which confirms loneliness and isolation as the main threat to the well-being and independence of female teachers.

Although the isolation of female teachers was a dominating theme, some teachers expressed caution regarding tenants as a solution. One of the female teachers who supported Roos argued in favor of tenants, but only “as long as no one can think of anything better.”Footnote 39 In 1914, Roos also received a statement signed by 284 female teachers that supported her proposal to provide apartments for rent in school buildings. This statement admitted the potential inconveniences of having a tenant in the school building, but also asserted that such a proposal would increase the security of female teachers, and that their isolation and exposure would best be counteracted with physical company.Footnote 40 The teachers argued:

We know how sad the consequences can be from the isolation, and it is our opinion that the value of the increased security for the solitary teachers, which would be won by the said proposal, would further outweigh the inconveniences that may possibly arise through tenants.Footnote 41

These female teachers thus confirmed the experience of isolation itself as a threat to the teachers, and by agreeing with the proposal to have tenants in the schoolhouse, they also agreed that isolation and threats would most easily be dealt with by having company.

Tenants and Telephones

The debate in the early 1910s was followed by political proposals. In 1914, two male members of the Swedish Parliament presented a bill with the express purpose of promoting the safety of female teachers. The authors of the bill noted the press's frequent reports of the dangers faced by female teachers living in solitary school buildings, and that many articles and letters spoke of burglary and assault. The authors of this bill also mentioned the anxiety that the teachers’ defenseless position caused them, knowing that they would not be able to call for help in their solitary state. The authors noted that no profession had as high a rate of mental disorders as female junior school teachers (småskolelärarinnor) had, and that there even was a case at one school where a series of four teachers had gone insane within a short period of time.Footnote 42

The male authors of this bill stressed the sexual vulnerability of the female teachers. According to them, men could hardly imagine the horror that many women faced and the fear they perceived as worse than death: to lose not only one's life, but one's honor. Therefore, if a female teacher had even only once experienced a drunkard's attempt to break into her apartment, it meant that each night she would listen for any suspicious sounds, which in turn could lead to mental disorders. The bill's authors noted the suggestion promoted by Roos, supported by what was described as almost three hundred teachers, and proposed a government investigation to examine possible solutions for increasing the safety of female teachers in solitary school buildings.Footnote 43

In the parliamentary debate that followed, the members discussed this and other proposals. Criticism targeting Anna Maria Roos's proposal noted again that allowing tenants in the school buildings might raise problems for the teachers. Other Parliament members noted practical challenges: finding tenants to relieve the teachers’ isolation would be difficult simply because the school buildings were so isolated. Parliament member Helger noted succinctly that no one would rent an apartment in an isolated school, stating, “It is true that in these schoolhouses, which are prone to be such lonely places, no one wants to rent a home.”Footnote 44 This comment certainly indicates that the teachers’ isolation was widely understood: their homes were so solitary that it was reasonable to believe that no one would willingly move there. In January 1915, the board of the Swedish Teachers’ Association (Folkskollärarföreningen) met and discussed (among other things) the living conditions of the teachers in the countryside. It rejected Roos's proposal to set up apartments for rent in school buildings: only 30 local associations supported this proposal, while 201 associations opposed it.Footnote 45 Most of the proposals presented by the board nevertheless focused on alleviating the teachers’ isolation, including proposals to merge the housing of female teachers and male primary school teachers where possible. Another suggestion was for female teachers’ housing to provide a room for a maid or a relative.

Another proposal was to provide the teachers in remote areas with telephones. Along with relieving the teachers’ isolation, it was designed to increase the teachers’ safety, although it was met with disapproval. Among those opposed was Parliament member Persson, who in his argument imagined a scenario where a stranger forced himself into the teacher's house with intent to harm her, in which case the intruder would hardly let her use the phone. Also, if her home was far removed from neighbors, it would take too long for help to arrive even if she had a telephone.Footnote 46 Persson's argument about the phones, like Helger's, was a further confirmation of the teachers’ isolation and vulnerable position.

This was not, however, a self-evident stance. The Swedish Teachers’ Association supported the proposal to provide telephones to countryside teachers, which seems to have had an impact at the local level. An example can be found in a note from a 1917 issue of the newspaper Jämtlands-Posten, which reported that a local school board, in response to the request by the Teachers’ Association, decided to “provide a telephone and a revolver” to a female teacher.Footnote 47

Despite the lively political debate, Parliament did not accept any specific proposals for improving the living conditions of female teachers. Even though the teachers’ isolation and vulnerability in the countryside seems to have been widely acknowledged, there was little inclination among the (male) Parliament members to strengthen the teachers’ position. Instead, a Parliament member would acknowledge the teachers’ situation, but also note that they were not, after all, obliged to seek employment in these solitary places.Footnote 48 The result of the parliamentary debate was thus minimal. The only measure taken was by the National School Board (Folkskoleöverstyrelsen), which in December 1916 distributed a letter to all Swedish school districts encouraging increased security for rural schoolmistresses. In January 1917, the National School Board submitted a proposal to the government for revising the Elementary School Act, which emphasized the importance of providing single female teachers with secure housing. This proposal was accepted, and a paragraph on how each school council was obliged to ensure the security of isolated female teachers was added to the national school act.Footnote 49

“A Rifle on the Wall and a Revolver in Your Pocket”

While the Swedish Parliament could not reach an agreement, additional proposals were presented in the press. Apart from those addressing the issue of isolation and loneliness, there were also some that intended to solve the problem of female teachers’ feelings of fear, exposure, and vulnerability.

One of the more practical suggestions for how to ensure the teachers’ safety was to arm them. Self-defense was not mentioned as a solution in any of the political bills from 1914, and it is also difficult to trace this idea through newspapers. The first proposal we found was in the newspaper Svenska Dagbladet in May 1914. Here, Miss Walborg Lagerwall urged female teachers to learn how to handle firearms. In her appeal, Lagerwall directly addressed the schoolmistresses, asserting that the teachers should not wait for political investigations and decisions to help them in their vulnerable situation. Instead, they should learn how to shoot. She wrote:

A rifle on the wall and a revolver in your pocket, now that is your best defense! The helpless little schoolmistress must instill respect, feel quick and uninhibited, and lose the fear of the dangerous firearms, which must instead become her good friends. The municipality will provide both weapons and ammunition, as it will be much cheaper than a guard dog, dog tax and dog food! Not to mention that the dog is most often poisoned or massacred by evil people. Learn immediately to shoot! Admittedly, we do not have the right to kill our assailants in self-defense, and no woman would go that far, but to injure him—for example in the leg—and thereby make him harmless, we dare. Therefore, learn to aim and shoot well! Raise the request in your municipalities, about weapons etc., and within a few days such a heartfelt appeal should be granted.Footnote 50

Lagerwall's contribution to the debate is notable, since it provides an alternative account of the experiences of rural female teachers. According to her, the problem was not loneliness but the threat of intrusive men. It is also interesting that the proposal put forward in this context is not about reforming structural conditions (e.g., improving the status of female teachers or the rights and position of women in general) or finding specific solutions for calling for help. Instead, possibly lethal violence is presented as the best solution, which challenges conventions about female agency and diverges from the political solutions to gender issues promoted in other contexts.Footnote 51 Lagerwall concluded her piece with a call to the female teachers: they should become shooting instructors and also teach girls how to shoot. Lagerwall's stance was that this was an opportunity to form “a voluntary female Landsturm” or territorial reserve to defend female teachers.

Although perhaps not as scrupulous as Lagerwall's proposal, other articles mentioned weapons as form of self-protection for female teachers. In June 1914, for example, a note in the established newspaper Svenska Dagbladet stated that the Board of Stockholm County (Stockholms län) proposed that all parishes should provide “suitable weapons of protection, such as revolvers” to all solitary rural schoolmistresses.Footnote 52 In 1917, newspapers included further examples of school councils all over the country deciding to purchase revolvers for rural schoolmistresses.Footnote 53 One news item did describe handguns as a particularly good solution, and not only for rural teachers. Although the article did not describe the school buildings as particularly isolated, it did note that the school board might still decide to procure a revolver for a female teacher.Footnote 54 This brief news item tells us that in the view of the press, even teachers who were not classified as solitary were still in such a vulnerable position that it was necessary to enable them to protect themselves.

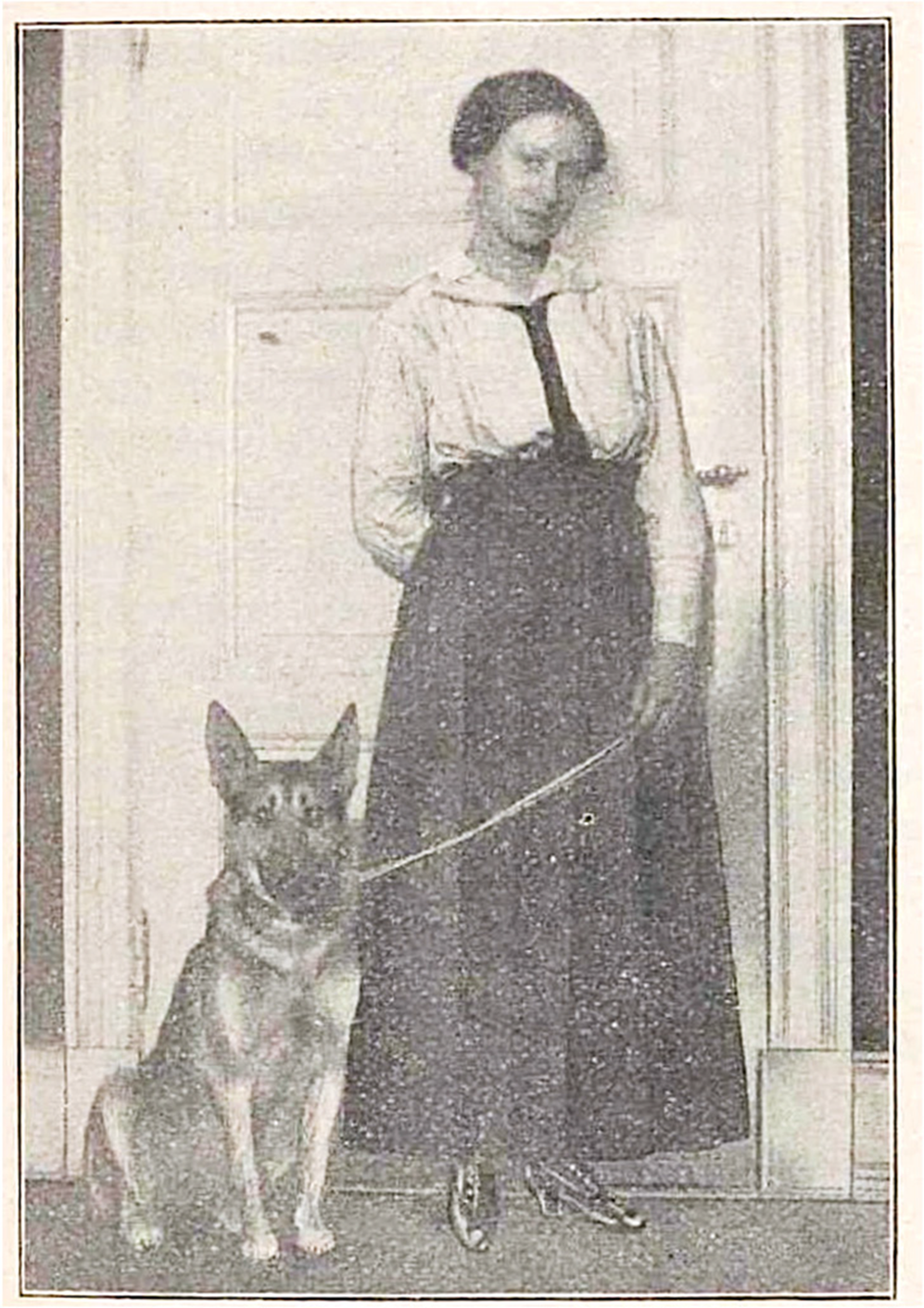

Not everyone involved in this debate was, however, in favor of arming lonely teachers. In 1917, an article in Dagens Nyheter argued that female teachers should be provided with a guard dog because handguns were not entirely suitable for women: “The revolver is, so to speak, a double-edged sword in a nervous woman's hand.”Footnote 55 Guard dogs were definitely not a novel solution to this problem. Newspapers published want ads from female teachers looking to buy or receive guard dogs—some noting preference for vicious dogs, others for dogs “not unnecessarily vicious”—while sellers also ran advertisements for dogs in teacher journals, including some proclaiming Rottweilers to be the best guard dog for solitary teachers.Footnote 56 Even the national police dog journal advocated trained dogs as protection for these teachers, giving as an example a depiction of a young female teacher with her trained German shepherd (see Figure 2).Footnote 57

Figure 2. A single-living teacher and her guard dog. Photo from Tidskriften Polishunden 1, no. 11 (1917), 67. Photographer: Unknown

In this discussion of weapons and other security measures, the female perspective was well represented. In 1916, following a high-profile attack against a female teacher in the village of Nöbbele, ten women's associations published joint proposals for how the security of female teachers could be strengthened, including providing their housing with fences, secure locks, and defining their housing as a national security zone.Footnote 58 Another important contribution came from the renowned feminist author and activist Elin Wägner. She supported the proposals signed by the ten women's associations, but argued that there were no easy fixes to the problem that not only included violent attacks such as that in Nöbbele, but also harassment (including impertinence, disturbing sounds at night, and stone throwing), low salaries, and isolationFootnote 59

In line with Elin Wägner's description of the issue, the weekly women's magazine Idun published a short story later the same year that commented on the debate and, in particular, whether it was appropriate to solve the problem with weapons or not.Footnote 60 The story describes a young teacher's loneliness and anxiety in a remote rural school. The author, herself a former schoolmistress, vividly depicts the problematic mix of emotions linked to loneliness. She notes the contrast between the teacher's experience of being raised in love and happiness and her loneliness in the shadows of the forest location of the solitary school building. This loneliness is not only physical but also mental, in that the teacher does not seem to understand her own predicament. According to the story's narrator, no one in the school district thinks about how such loneliness makes the human heart long for happiness and sunlight, and how the heart hungers and withers in isolation.

In such a state of loneliness, a weapon would obviously not provide solace for the lonely teacher. In the short story, however, the school board acknowledges the teacher's concern and provides her with a revolver. But, as the narrator notes, “it is not bullets and gunpowder, not double doors, not shutters or barbed wire fences, not telephone lines a lonely woman-child needs; but instead living people, who you can look at, hear and talk to.”Footnote 61 In the story, isolation from human company is a bigger problem than threatening and intrusive men; thus the author problematizes the actual importance of the handgun to the vulnerable teachers: loneliness and the absence of social interaction could not be solved by technical solutions.

The story illustrates this argument through a particular event occurring one late night, when some travelers knock on the teacher's door and ask for directions. In this situation, the revolver is not a comfort. Instead, after the visitors leave, the teacher stays awake listening for strange noises until she falls asleep, only to be awakened later with fever. The revolver is indeed useless as an antidote to loneliness and anxiety. Instead, it lies at the teacher's side, mocking her helplessness through the “terrible silence” of the night. In the story, the teacher's isolation serves as an additional argument against handguns. Given her isolation and the concerns about mental health, would a female teacher under such circumstances really be able to handle a revolver?Footnote 62

1930s: A New Search for Solutions

After the debate in the 1910s in which newspapers, teacher associations, women's associations, the National School Board, and even the Swedish Parliament got involved, the debate returned in the late 1930s. The main reason for its return was the 1937 publication of a study of female teachers’ living conditions, authored by Olof Olsson in the journal Tiden.Footnote 63 This study, which focused on the female teachers’ living conditions in the 1920s and 1930s, highlighted economic aspects of everyday life as well as mental and physical health. It showed that the danger that lonely female teachers were exposed to in their own homes put them at risk of becoming mentally or physically ill. Olsson corroborated his study with statistics illustrating how common it was for young female teachers to prematurely leave their position and how ill they often were. He stressed that among other actions, breaking the solitude of teachers was crucial.Footnote 64

After this investigation, the debate focused largely on loneliness and telephones as a solution to the challenges that female teachers faced. In turn, it formed the basis for a bill submitted to Parliament in early 1938 that provided an overview of the debate reaching back to 1914, recalling some of the well-known cases of violence against female teachers. The author's bills presented modernization not as a contributor to teachers’ loneliness but as a way to alleviate it. The authors noted that improved communications most certainly would relieve female teachers of some of their isolation. There would be no more unfortunate cases such as that of a teacher who, in her first year of service, was completely isolated by a snowstorm for several days and thereafter suffered mental illness. However, the bill's authors noted that assaults on female teachers still occurred and that the teachers’ mental health still suffered because of their isolation. Although their work was hard, their loneliness was an even heavier burden to bear, and the sense of loneliness could create an agonizing anxiety.Footnote 65 The bill's solution was to offer government grants for installing telephones for solitary female teachers in the countryside.

The bill was supported by the National School Board (Skolöverstyrelsen),Footnote 66 the National Board of Health and Welfare (Socialstyrelsen), and the Swedish Teachers’ Association. The newspapers also welcomed the proposal; for example, a commentary in Svenska Dagbladet emphasized the difference that the telephone would make for the lone teacher, describing it as the best solution among other potential options such as guard dogs and alarm bells. By providing human contact, which the commentary described as something that would “otherwise be entirely withheld from these teachers,” telephones enabled teachers to never be far from friends and family.Footnote 67 Like the parliamentary bill, this commentary also argued that the problem for the teachers was primarily about their isolation and lack of social contacts, which could lay the groundwork for mental illness, but that this problem could easily be ameliorated by contact with the outside world via telephone. The conservative newspaper Lunds Dagblad, however, pointed out that a telephone would not protect a teacher from unlawful entry or assault at night (when the risk of such crimes was higher) because the telephone stations in the countryside closed early.Footnote 68

The telephone bill met with heated debate in Parliament.Footnote 69 It showed a continuity with the debate that had started twenty years earlier, in that unmarried female teachers in rural areas remained in a vulnerable position and their living conditions had not significantly improved. The debate also showed that the approach to the issue of gender equality was very “hands on” and mainly focused on practical solutions.

Several members of Parliament opposed the bill, noting among other things that a telephone would still not provide security in case of assault in a teacher's home. Parliament member Andersson argued that a burglar could easily cut the telephone wires outside a teacher's house before committing the burglary. Andersson also pointed out that there were many other occupational groups that lived more or less isolated lives, such as forest workers. If teachers were to get telephones, these other isolated groups should also receive them “in the name of justice.”Footnote 70 Furthermore, Andersson argued that the telephone stations were closed in the evening, rendering them useless during that time.

Other members of Parliament also argued against providing female teachers with telephones. Another parliament member, Åkerström, even claimed that the presence of a phone in the teacher's house could negatively affect her mental well-being. If her home was in an area where not many people had a telephone, there was a risk that she would be annoyed by a “constant coming and going of neighbors who wanted or needed to borrow the phone, and this, said Åkerström, could put a strain the teacher's mental state.

Most critical in the debate, however, was the stance of Parliament member Gustavsson. He completely withdrew from the proposal, firmly stating that women should have no advantages whatsoever over men, arguing that women themselves had sought to be treated on the same terms. For Gustavsson, the main problem was not a female teacher's experience of loneliness, but her inability to deal with it. If their “fragile nerves” could not handle such a situation, then they should not be pampered and thus should not be employed as teachers.Footnote 71

Although several members of Parliament agreed with Gustavsson, several others didn't. Parliament member Ekdal was, for example, strongly critical of Gustavsson's remarks and said that they insulted the country's teachers as a whole. Several Parliament members who endorsed the proposal pointed out that giving teachers the best conditions for security and mental well-being was a way of ensuring the quality of education. However, after the debate, the proposal for a telephone grant to female rural teachers was voted down, with sixty-five members voting in favor and seventy-three voting against.

The daily press criticized the proposal's rejection, and targeted Gustavsson's statements in particular. On the question of whether a telephone would be helpful to the teachers, other benefits were raised. In Svenska Dagbladet, a writer with the initials “E.S.P.” stated that the debate had overlooked several of the more general benefits of letting the teachers have a telephone. For instance, a teacher could call for assistance in case of illness or an accident at the school, or they could contact worried parents.Footnote 72

Others mentioned again the problem of loneliness. For example, in an interview with Svenska Dagbladet, teachers from Tornedalen (in the absolute north of Sweden) voiced their disappointment that the telephone proposal had not been accepted. They noted female teachers’ vulnerable positions in the countryside and the emotional challenges of being isolated in the dark of night, when the anxiety of loneliness creeps in. In those circumstances, being able to talk to neighbors on the phone would be a great comfort, they argued.Footnote 73

This proposal to reduce the isolation of female teachers eventually won support. In 1939, during a more general debate about the expansion of the national telephone and telegraph system, those in favor of the motion cited the remote position of female teachers in rural areas.Footnote 74 Parliament voted in favor of the bill, which resulted in progress for telecommunications in Sweden, and consequently also ended the public debate about the isolation and loneliness of the rural female teacher.

Conclusion

In relation to the extensive research done on the feminization of the teaching profession, the aim of this article may be formulated in terms of a retrospective experiment: What happened when female teachers were employed in rural twentieth-century Sweden? As evident from this article, one of the results was a public debate about female teachers that addressed their living conditions and experiences, both of which were perceived as problematic. In addition to a gender gap in salaries and status, this public debate indicated that there was also a gender gap with respect to the loneliness, harassment, and violence that single female teachers suffered. Although the feminization of the teaching profession certainly was a part of the emancipation of women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century—a period that saw important progress in terms of political franchise for women—this article demonstrates that the fruits of this development could not be enjoyed by all its pioneers in rural Sweden.

The vulnerability of female teachers was partly a matter of male violence. By living alone in the countryside, female teachers had a solitary position that made them easy targets as they could neither defend themselves nor call for help. However, this vulnerability was also a matter of loneliness. Here, the threat to a female teacher's health was not men, but the constant silence and the absence of social interaction. Contemporary arguments held that these challenges posed by isolation could combine with and feed on each other, and that the fear of assault could grow even stronger during long and lonely nights.

Solutions to the precarious position that female teachers found themselves in varied. Those who perceived men as the main problem proposed alarm bells, guard dogs, and even handguns for improving the teachers’ living conditions. Those who perceived isolation as the main problem proposed that school buildings rent rooms to tenants or install telephones.

The analysis clearly shows that the emotions of the teachers played a prominent role in the debate. While fear and loneliness certainly were not new experiences for early twentieth-century female teachers in rural settings, the public debate indicates that these feelings had now become an unacceptable problem that needed a solution. Although loneliness, terrible silences, and anxiety were hardly unique to this group of women, this range of emotions was now publicly discussed and debated in calls for providing female teachers with protection not only against men but also against isolation. In this context, we note that it was not only the female teachers themselves who, when given a voice in the debate, referred to emotions in their arguments—but also those who took their side. Incidents appearing in newspapers were used as examples of the teachers’ poor living conditions, but descriptions of their depression and anxiety were the source of even stronger and more persistent arguments in the public and political debate. The solutions discussed were practical, but the arguments that legitimized the debate were reflections of the teachers’ emotions.

By examining how these problems and solutions were formulated, this article broadens our understanding of what it meant to be a female rural teacher in the early twentieth century. It was not just about gender differences in salary and status, but also about fear and loneliness—feelings that we today, after the dissolution of rural village schools and the expansion of telephone lines, might have a hard time imagining. To the studies of female teachers’ salaries, levels of status, and identities, this article thus provides additional insights into the experiences of these teachers, and what loneliness meant in terms of anxiety, to a group of teachers facing darkness, silence, long nights, and potential assaults.

This article also provides further insights into the professional struggles of teachers, not only in terms of formal working conditions, but also in terms of security and social interaction. These stories and discussions give a glimpse into a kind of women's struggle that was conducted far from politics or abstract debates about social, educational, and political rights—instead, the struggle was about actual problems in the teachers’ everyday lives. The debate and the political proposals show that the ambition was not to change society or individuals, but simply to improve the situation of female teachers. This desire was most evident in the proposals to provide female teachers with weapons. Instead of making proposals aimed at reforming an unequal society marked by male violence, or to emancipate or empower female teachers, providing teachers with handguns was merely a method for enabling female teachers to defend themselves in a hostile rural society. In this respect, this article sheds light on a struggle that is still recognizable in the era of #MeToo, but differs in terms of context and solutions.

Finally, the public debate concerning female teachers’ experiences of loneliness and vulnerability raises questions of why these issues were first debated in the early twentieth century. These feelings were certainly not unique to this group of female teachers, as previous generations must have experienced them. Apart from the construction of the primary school system in rural Sweden, which meant that increasing numbers of single women were increasingly housed in sparsely populated areas, the positions of these female teachers were probably an important reason for the debate. Unlike other underpaid and undervalued women, female teachers were a group that was easily identified; they had vocal advocates in teacher associations and women's associations and among female authors; and their functional role in the educational system (and by extension, the nation) was easily evident. As was noted in the journal Hertha, it was in the interest of the Swedish state to protect its own female servants.Footnote 75 Although the suffering of female teachers may be understood as a result of their subordination in a patriarchal society, the public acknowledgment of their experiences was the result of their relative strong social standing in comparison to other groups of women in early twentieth-century Sweden.

Sara Backman Prytz is a historian of education and an assistant professor at Uppsala University, Sweden.

Johannes Westberg is full professor of theory and history of education at the University of Groningen, Netherlands.

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.