Background

In provision of psychiatric services to people with intellectual disability, several factors result in patients and carers experiencing difficulty in attending out-patient appointments.Reference Whittle, Fisher, Reppermund, Lenroot and Trollor1 As intellectual disability services often cater for large geographical areas, these factors include inconvenient travel.2

In the UK, there is an emphasis on finding efficiencies and providing cost reductions to address the political austerity agenda.3 The Transforming Care report4 for people with intellectual disability itself cited cost savings for patients returning to the community. Additionally, there is a growing movement towards a more environmentally conscious provision of service.Reference Naylor and Appleby5–7 Telepsychiatry8 consultations, on the surface, would appear to aid with these issues.Reference Bashshur, Shannon, Bashshur and Yellowlees9–Reference García-Lizana and Muñoz-Mayorga11

Telepsychiatry has been broadly defined as the use of information and communication technology to provide or support psychiatric services across distances.Reference Malhotra, Chakrabarti and Shah10 The General Medical Council12 and the American Psychiatric Association13 have produced guidance on the fields of telemedicine and telepsychiatry, respectively. Notably, issues such as practicalities (including security, confidentiality, patient and provider identification, logistics, patient selection, prescribing responsibilities and reliability of equipment), as well as ethical issues including appropriate ability to escalate emergencies, are highlighted as important in such a modality.

Several reviews have focused on telepsychiatry and autism.Reference Boisvert, Lang, Andrianopoulos and Boscardin14–Reference Oberleitner and Laxminarayan16 Many people with intellectual disability have comorbid autism; however, the reverse is not always the case.Reference Matson and Shoemaker17 Therefore, extrapolation of studies in telepsychiatry with autism, unless intellectual disability is explicitly stated, may mask the underlying needs of those with intellectual disability. Although a brief review of intellectual disability in telepsychiatry exists in the literature,Reference Krysta, Krzystanek, Cubała, Wiglusz, Jakuszkowiak-Wojten and Gałuszko-Węgielnik18 this was methodologically flawed, as searches were limited to PubMed, resulting in omission and limited synthesis with inclusion of student teaching rather than telepsychiatry (patient-directed care).

Several innovative telepsychiatry services have been developed for use in adult, forensic, and child and adolescent mainstream (i.e. non-intellectual disability) mental health services.Reference Antonacci, Bloch, Saeed, Yildirim and Talley19–Reference Sales, McSweeney, Saleem and Khalifa22 These, however, do not focus on the key issues encountered by the intellectual disability patient group and the specialist psychiatric services that serve them.

Aims

The aims of this review were to explore the effectiveness and patient and provider acceptability of telepsychiatry consultations in intellectual disability, contrasting this with direct face-to-face consultations and proposing avenues for further research and innovation.

Methods

Search strategy

A computerised search was undertaken on 10 June 2018 using the following databases: Cochrane Library, AMED, BNI, CINAHL, EMBASE, Medline, PubMed and PsychINFO. The search was of English language, peer reviewed journals for all dates available published in the respective databases.

Search terms were kept broad, to include as many studies as possible and account for the different terminology used internationally and over time for intellectual disability. The grey literature (opengrey.eu) was also searched to avoid missing relevant publications. References from papers that were selected by the search were also included if suitable studies were encountered.

The search terms for title and abstract were: (telepsych*) AND (mental* OR intellect* OR development* OR learning*) AND (deficien* OR disabilit* OR disabl* OR retard* OR disorder* OR impair* OR handicap*).

Study selection

Papers considered eligible for inclusion in this review included those where: (a) the participants were mental healthcare patients (adults or children) who were classified as having an intellectual disability; and (b) the intervention described was telepsychiatry, i.e. live synchronous or asynchronous videoconference-based clinical psychiatry. English abstracts of non-English articles were reviewed where available.

Papers were excluded where participants did not have an intellectual disability, there was no telepsychiatric intervention, or they were general review papers on telemedicine.

The titles and abstracts of reviews were identified, screened and classified for extraction of full review for further analysis by the author.

Results

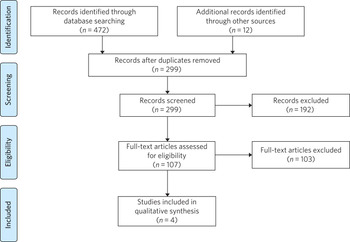

A record of the searches is provided in Fig. 1. A total of 472 records were identified by database searches. A further 12 were retrieved by hand-searching from references. Of the 472 studies, 185 were duplicates and the remaining 299 were screened with abstracts reviewed by the author. The majority of exclusions were on the basis of the article having no clear reference to people with intellectual disability. At this stage, 107 articles were selected, including several involving participants with autism where further information was required to determine whether an intellectual disability was also present.

Fig. 1 Results of literature review search strategy.

Upon reviewing the full text of these studies, a further 103 were excluded. In these cases, the articles were opinion, commentary or editorial pieces, primary research, or addressing autism but not concerning patient groups with intellectual disability. Four studies were included in the qualitative synthesis; a summary is provided in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

ID, intellectual disability.

Study location

All studies took place in North America. Two of the studies took place in Ohio but were run by separate teams in different locations. The telepsychiatry care was provided in schools, hospitals and homes. All studies appeared to be funded by non-commercial sources.

Study designs

There were no randomised controlled trials identified. The Harper study used control groups that were evaluated on site rather than through a telepsychiatry modality and were matched using age, gender, socioeconomic status and problem type. The Langkamp study provided access to a primary care physician; while this was not a study of a psychiatric service, it was included as the cases described illustrated patient types likely to be seen in a UK intellectual disability service.

Study populations

Most studies (three) focused on children with intellectual disability, while the remaining study (GentileReference Gentile, Cowan, Harper, Mast and Merrill23) included both children and adults with intellectual disability.

Sample size

Sample sizes of people with intellectual disability were unclear in two studies (HarperReference Harper24 and LangkampReference Langkamp, McManus and Blakemore25); however the sample sizes of the others ranged from 38 to 900 participants.

Interventions

Broadly categorised, the interventions in this review included psychiatric assessment and psychiatric follow-up, provided using a telepsychiatry service. Prior to the development of the telepsychiatry service, consultations were provided in a standard face-to-face model. Studies included in this paper used both asynchronous and synchronous connections, with the latter being more common (three studies). Synchronous services provide live, two-way interactive transmission at geographically separate locations,Reference Malhotra, Chakrabarti and Shah10 thereby simulating face-to-face interviewing. Asynchronous services, by contrast, do not require the presence of both parties at the same time, and have the advantages of being relatively inexpensive and not requiring any special hardware support. The information can be transferred in the form of data, audio, video clips or recordings, and can be done by email or web applications for review by a specialist at a later date.

Length of follow-up

Follow-up length varied from 1 to 6 years.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures varied considerably across the research studies and included cost savings to both patients and healthcare providers, patient and carer satisfaction, new diagnoses and medication changes.

Notably, there was a 96% decrease in emergency room visits (GentileReference Gentile, Cowan, Harper, Mast and Merrill23) in the 12 months following treatment via the telepsychiatry model compared with the preceding 12 months. The authors of that study suggest that teams have access to nursing and medical staff between appointments to assist in problem-solving in real time when issues occur between appointments. They also discuss how staff provide education on de-escalation techniques and options when patients exhibit behavioural change. Although a remarkable 96% decrease was noted, one would question the practice that existed prior to the telepsychiatry model. It is likely that, as there was limited access to local professionals before, the patients and carers may have been able to access professionals remotely. Further information on this would have been useful to balance the use of high-cost medical services with multiple accesses to lower-cost services.

Gentile described hospital admissions decreasing by 85%. The authors also noted that of their first 120 subjects, none had been admitted or readmitted to state-operated institutions. They estimated the state of Ohio saving approximately US$80 000 per person per year in support costs. As above, more information on the frequency of contacts would have been useful. Although the study highlights several patients historically having had to use state-operated institutions, it cannot necessarily be concluded that the telepsychiatry intervention was the only reason there were no admissions or readmissions.

HarperReference Harper24 noted a positive attitude to their telemedicine group, with 98% stating that the experience was the same or more positive. Some parents (12%) reported technical problems such as poor audio and camera movement. Professionals rated the consultations as comparable to face-to-face consultations. There were no significant differences in consultation time. Over the time period, the authors evaluated costs including time, travel and mileage. They concluded that the average saving to the local district (professional and patterns) was US$971 per telemedicine session. Additionally, the average saving for parents was estimated to be US$125 per session, and fewer parents missed work.

Although there was no breakdown of cases in the LangkampReference Langkamp, McManus and Blakemore25 study, the case studies included one illustrating a 10-year-old girl with intellectual disability and agitation. The authors comment that her parents were absent from work for healthcare visits less often as a result of using the telemedical link. The parents also reported appreciating their child receiving quality medical care without becoming excessively distressed.

SzeftelReference Szeftel, Federico, Hakak, Szeftel and Jacobson26 and colleagues reported their patients as being seen six times on average in the first year, and three times per year in the second and third years. Severity and number of symptoms were noted to have decreased over the three years, with fewer visits as treatment progressed and fewer medication changes. The authors noted that changes in medication, either in dosage or type, tended to take place in the first rather than in later appointments, with 82% of patients having a recommended medication change at the initial assessment; this may suggest an emphasis on a biological rather than a holistic approach.

Discussion

This study is the first review to undertake a comprehensive synthesis of telepsychiatry in intellectual disability. There were two major findings: (a) very few reports of such studies exist; (b) all studies took place in North America. Unfortunately, it is therefore difficult to draw firm conclusions about the benefits and constraints of such a modality in this population group. The majority of the studies had relatively low sample sizes and focused on a single nation's health infrastructure (USA); hence, extrapolation to other populations and to other countries is potentially erroneous.

Unsurprisingly, most studies focused on children, given the relative ease of implementing such systems in children's services (as children attend schools and are more likely to have parents as guardians). It is therefore difficult to extrapolate satisfaction levels of parents to those of adult patients receiving such services. Information on exact numbers of patients with intellectual disability and mental illness or challenging behaviour was missing in half the studies. None of the studies discussed any legal implications of using remote services and storage of video data, nor how to escalate difficulties if and when they arose.

The absence of randomised controlled trials, the gold standard in research study design, was a major flaw in these studies – and, in fact, in telepsychiatry research as a whole.Reference Richardson, Frueh, Grubaugh, Egede and Elhai27 Furthermore, it is possible that there are commercial intellectual disability telepsychiatry services who have not published their data for economically sensitive reasons and have therefore been missed by the searches.

However, despite these limitations, it would be irresponsible to dismiss this body of evidence when taken in the context of the telepsychiatry and general telemedical literature. Most notably, several reviews of telepsychiatry in autismReference Boisvert, Lang, Andrianopoulos and Boscardin14–Reference Oberleitner and Laxminarayan16 have been conducted; these offer some overlapping features that could benefit those considering setting up telepsychiatry services in intellectual disability in other countries. There are potential legal and technological issues that could restrict the development of this field, and contextualising other non-intellectual disability studies could benefit such service innovators. GreenhalghReference Greenhalgh, Shaw, Wherton, Vijayaraghavan, Morris and Bhattacharya28 and colleagues recently conducted a mixed-method study on video out-patient consultations, in which it was concluded that despite such consultations appearing convenient, safe and effective, this was only in patients judged clinically appropriate and was a fraction of the overall clinic workload. The paper also highlights that the National Health Service appears to be a difficult setting in which to introduce technologies that imply major changes in service models.

The studies overall suggested positive effects of the telepsychiatry model for intellectual disability patients. Notably, an often-considered concern from professionals regarding remote consultations is the loss of subtleties and direct relationships that are built with face-to-face appointments. These studies and the literature as a wholeReference O'Reilly, Bishop, Maddox, Hutchinson, Fisman and Takhar29 do not support this. In fact, there is even evidence that children with severe anxiety and autism can be more engaged during a telepsychiatry consultation.Reference Pakyurek, Yellowlees and Hilty30

In addition, there are notable savings to services, both directly and in prevention of future hospital admissions, which are likely to appeal to service providers. When this is taken in the context of the positive patient and carer satisfaction results noted in the studies, it is surprising there has not been a larger uptake of telepsychiatry services in intellectual disability. If they develop sufficiently, such services may become eventually be classified as a reasonable adjustment as per the UK Disability Discrimination Act. In fact, the most recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline31 for care and support of people growing older with learning disabilities includes specific advice to ‘consider the use of technologies such as telehealth and telecare to complement but not replace the support provided by people face to face’.

All studies identified were conducted in North America; no published UK or European studies were found. This is surprising, as the UK has a faculty of intellectual disability at the Royal College of Psychiatry (https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/workinpsychiatry/faculties/intellectualdisability1.aspx) and a well-established training scheme for psychiatrists to specialise in intellectual disability psychiatry,32 as well as highly active patient advocate groups such as Mencap33 and the Challenging Behaviour Foundation.34 However, psychiatric services are generally be closer to patient populations when compared with the USA. Of the locations mentioned in the studies identified, Iowa is significantly low in population density (21/km2) when compared with California and Ohio (93 and 109/km2, respectively),35 although it is recorded as having more urban than rural population. In the UK, the population is more dense (271/km2)36 overall, with an estimate of 83% of the population living in an urban setting.37 However, it is notable in the UK that many on-call rotas are non-residential, covering large geographical regions; thus, the application of telepsychiatry could benefit both patients and a significant proportion of psychiatrists who work with intellectual disability patients.

Nevertheless, despite the identified studies focusing on intellectual disability services for children, the transition period from child and adolescent mental health services to adult services could be a positive avenue of research. Collaborative multi-professional appointments may in fact ease the transition, and research involving telepsychiatry could help to determine whether this is the case.Reference Clarke, Sloper, Moran, Cusworth, Franklin and Beecham38, Reference Singh, Anderson, Liabo and Ganeshamoorthy39 This is often a difficult period for patients, carers and professionals, particularly for those with intellectual disability.

More research in this field would be welcomed for less-developed and more geographically spaced-out healthcare systems. Implementing both synchronous and asynchronous remote consultations using some of the more accessible, encrypted and mainstream video streaming services with intellectual disability population groups is likely to become more feasible, given that broadband services (and reductions in costs) have permeated much of the globe, including geographically isolated areas. Further research in less-developed countries as well as in other healthcare systems would help to build a more robust literature and facilitate innovation in this field. The rolling out of broadband services across other nations, including the UK, has been relatively slow in comparison with the USA; this may partly explain the lack of telepsychiatry services, which require reasonable connection speeds.

Additionally, as costs of technology such as secure smartphone devices and cheap encrypted applications decrease and data connection speeds increase, it is likely that more healthcare providers internationally may consider both implementing telepsychiatry services and sharing their outcome data in the peer-reviewed literature. Integrating the findings would therefore enable best practice guidelines to be developed, for example.

None of the studies in this review mentioned the use of interpreters; their incorporation into telepsychiatry, whether for Makaton, other forms of signing or in fact more mainstream language translation, is another potential avenue of research.Reference Lopez, Cruz, Lazarus, Webster, Jones and Weinstein40, Reference Mucic41

It is feasible that access to expertise via international collaborations using asynchronous methods or taking advantage of time zone differences for synchronous methods could enable, for example, vulnerable intellectual disability populations in underserved areas to access specialist intellectual disability psychiatric care to aid in reducing mental distress. Additional health economic and environmental evaluations in differing healthcare systems could also clarify whether similar models of care are transposable to such systems. Specific evaluation of environmental benefits or effects would also be a useful outcome to evaluate in further research.

Conclusions

This study identified four telemedical psychiatric consultation studies in intellectual disability, mainly limited to children. While there is some evidence of cost-effectiveness, improvement in patient and carer satisfaction, and convenience, the fact that there were relatively few studies limited to North America would suggest there is a need to explore further these novel methods of enhancing current psychiatric services.

Telepsychiatry models appear to aid in the empowerment of this patient group, as well as providing cost savings. However, further studies are required in other countries and across a wider age range before concluding that telepsychiatry in intellectual disability is an effective, acceptable and satisfying approach for providing psychiatric services for this underserved population group.

About the author

Giri Madhavan is a Specialist Trainee (ST6) in Psychiatry of Intellectual Disability at Coventry and Warwickshire Partnership NHS Trust, Coventry, UK.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.