Introduction

When referring to biological, psychological, social and institutional aspects of people’s lives, the term ‘resilience’ is best used to describe processes whereby individuals interact with their environments in ways that facilitate positive psychological, physical and social development. While earlier definitions emphasised individual traits and the invulnerability of individuals who coped well with adversity (Reference Anthony and CohlerAnthony and Cohler, 1987), more contextualised research has challenged the neoliberal bias of these earlier studies (Reference Sanders, Munford, Thimasarn-Anwar, Liebenberg and UngarSanders et al., 2015). When resilience was described as a trait, even if those traits were malleable, the implication was that individuals had the responsibility to develop the qualities necessary for optimal development, whether physical, psychological or social (like attachments). Resilience as a process, however, shifts the focus from individual responsibility for change to the interactions between individuals and their environments (Reference Birgden, Arrigo and WardBirgden, 2015; Reference UngarUngar, 2015). The environment, whether referring to legal institutions, community services or the availability of intimate bonds and other antecedents of mental health (e.g., a sense of coherence [Reference AntonovskyAntonovsky, 1996; Reference Mittelmark, Bull, Daniel, Urke, Mittelmark, Sagy, Eriksson, Bauer, Pelikan, Lindström and EspnesMittelmark et al., 2017]), combines to provide individuals with the internal and external resources necessary to cope with exceptional and uncommon stressors. For this reason, when resilience is understood as a process involving multiple systems, the responsibility for optimal functioning (whether psychological well-being or peace and security) under stress is shared across many different systems and at different scales (Reference UngarUngar, 2018).

It is this understanding of resilience that informs a deeper analysis of how systems, including those concerned with governance, education, health, human rights and law, influence the ability of populations to survive and thrive in contexts where there has been exposure to extreme forms of marginalisation (e.g., racism, homophobia, poverty) or social disruption (e.g., civil war, genocide). Stabilising and improving these systems is an important and necessary part of transitional justice work and related security-oriented practices like adaptive peacebuilding (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018; see also Chapter 11). This is especially the case when systems at the individual, family, community, national and international levels are involved at the same time in the provision of resources that people need to overcome histories of violence. Put simply, resilience, like transitional justice, requires the engagement of many different systems to create the individual and social capital necessary to cope well with adversity.

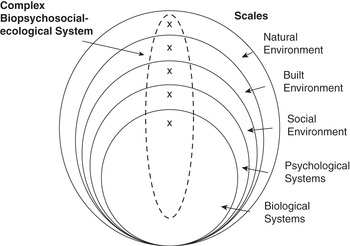

Figure 1.1 illustrates the nested relationships between these systems, with a subsystem of elements (the Xs) forming their own system comprised of the many resources required to sustain the well-being of both the individual and the individual’s community. To think about resilience at a single level, like a change in cognition or the exercise of human rights, misattributes change to the qualities of one system and risks making any change that does occur unsustainable. When multiple systems at multiple scales change at the same time, the work they do together produces a more enduring pattern of change and transformation. In practice, this means that efforts to promote transitional justice, like the interventions discussed throughout this volume, will produce the most sustainable resilience across a population when they address the systemic dimensions of war crimes and human rights abuses – and engage with different systems that give people access to new resources.

Figure 1.1 An ecological and multi-systemic model of resilience

This discussion of commonalities between resilience and transitional justice addresses a gap in both fields, with far too little of the resilience literature paying attention to structural and judicial processes that create the conditions for people to recover from mass violence (see, e.g., Chapter 9). Likewise, transitional justice literature has rarely discussed the impact of transitional justice mechanisms – including criminal trials, truth and reconciliation commissions (TRCs) or reparations – on the resilience of a community, or the need to think ecologically about the many systems that interact (or conflict) when transitional justice processes are utilised. For example, criminal trials to address war crimes may become extremely divisive for communities, disrupting social cohesion or even traumatising some victims, even as they appear to re-establish order with regard to governance and the rule of law (Reference ClarkClark, 2014; see also Chapter 3, this volume). The science of resilience helps to explain these dynamic feedback loops in which one system’s resilience can trigger another’s success or undermine the ability of co-occurring systems to function at all.

Fortunately, in recent years, a more multidisciplinary body of research on resilience has grown to include studies of biological human systems like the microbiome (Reference Rea, Dinan and CryanRea et al., 2016), human-environment systems like epigenetics (Reference Bush, Boyce and CicchettiBush and Boyce, 2016), workplaces (Reference CraneCrane, 2017) and the natural ecologies with which humans interact – such as coral reefs, forests and wetlands (Reference Adger, Barnett, Brown, Marshall and O’BrienAdger et al., 2013). Governance and legal systems shape the context for each of these interactions, from influencing the availability of food people need to maintain health to regulating the development of farmland in nature preserves. The relationship between these systems and resilience nevertheless remains underexplored. Key processes within these broader governance and legal architectures, for example – including the promotion of human rights, peacebuilding and the restoration of rule of law – are seldom discussed through a resilience lens.

An emerging body of work on therapeutic jurisprudence (Reference WexlerWexler, 2008; Reference WinickWinick, 2009), however, is starting to address this shortcoming, by studying the impact on individual well-being of formal legal institutions, criminal trials and TRCs (Reference DoakDoak, 2011), and looking at whether new initiatives like drug courts and restorative justice improve the desistance of offenders (Reference Birgden, Arrigo and WardBirgden et al., 2015). Nevertheless, more research is needed to account for what occurs at multiple systemic levels when victims of crime seek justice. For example, we know little about the impact of transitional justice processes on victims’ mental health during and after these processes, or about how these processes affect the functioning and sustainability of other human systems like community cohesion or extended family dynamics. Fundamentally, we know little about how transitional justice and peacebuilding processes more generally can transform psychological and social systems.

It also remains the case that there is little cross-fertilisation of ideas across the fields of resilience, law, transitional justice and human rights. This is part of a wider problem; network citation analyses show that there is little transdisciplinary exchange across domains of resilience research (Reference Xu and KajikawaXu and Kajikawa, 2017). This may explain why the connection between the resilience of one system and the resilience of co-occurring systems at different scales has yet to be well explained. Further compounding the problem is the fact that definitional ambiguity exists in all fields of resilience research, although this is an issue now being addressed on many fronts (see, e.g., Reference Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick and YehudaSouthwick et al., 2014).

The present volume addresses these various challenges. In this chapter, I will introduce the concept of resilience as a multi-systemic set of processes, an idea that is common to all the chapters that follow. I will then briefly show how these processes are relevant to governance, legal systems and transitional justice. The chapter will also discuss several concepts that must be accounted for when detailing the resilience of any system. These concepts include equifinality, multifinality and differential impact. Though this volume is focused on the systems involved in transitional justice and their resilience-enabling processes, potential or actual, this chapter will look more broadly at different resilience enablers in order to show that initiatives to tackle impunity, deliver justice and foster social healing and reconciliation are consistent with the principles that govern the resilience of all human systems.

A Multi-systemic Understanding of Resilience

In Rwanda after Genocide, Caroline Williamson Reference SinaloSinalo (2018) describes her narrative analysis of victims’ accounts of the genocide that unfolded during the early 1990s. Sinalo takes a controversial approach to the subject, first by arguing that there were many dysfunctional systems to blame for the atrocities, from the practices of past colonial governments to Rwandan norms regarding masculinity and warriorhood. She also, however, asserts that one can find examples of personal and social growth (also known as post-traumatic growth [Reference Tedeschi and CalhounTedeschi and Calhoun, 2004]) among survivors of the genocide – growth that is mirrored at the level of community governance, social cohesion and legal processes that have come into place since 1994.

To see this growth, one must challenge Eurocentric discourses that view trauma as the result of exposure to single episodes of an atypical stressor. According to Reference CrapsCraps (2013), trauma is more an everyday and insidious phenomenon than an unusual event. This is especially true for those who are marginalised, whether living in economically developed countries as minorities or in low- and middle-income countries, many of these with long and violent histories of colonisation (Reference Atallah, Bacigalupe and RepettoAtallah et al., 2019). In both contexts, poverty, racism and the intersectionality of multiple forms of oppression make trauma quotidian because of institutionalised forms of exclusion and dysfunction (e.g., corruption). In such a case, resilience can resist the effects of coloniality and reinforce models of Indigenous well-being (Reference SinaloSinalo, 2018).

This perspective of why atrocities occur and where responsibility lies for social repair positions resilience in a collective discourse of shared causality and complex systems. Addressing past or present human rights abuses cannot be accomplished by any one system alone. Multiple social and institutional factors must be involved, which, in turn, affect and are affected by individual responses to trauma and the continuity of those changes across time and even generations. Resilience-enablers (Reference Van Breda and Theronvan Breda and Theron, 2018) occur at multiple levels, refuting the idea that individuals bounce back from adversity, or bounce forward to new patterns of coping on their own. There is, of course, more to this critique than a simple vilification of neoliberalism. As Reference Hall and LamontHall and Lamont (2013) argue, a heightened sense of personal responsibility inherent in neoliberalism may have harmed many, but it has also opened opportunities for wealth generation on a scale never before seen in human history.

A better critique would be to understand how neoliberalism has blinded us to the locus of control of systems that must cope with extraordinary circumstances. Individual capacity to look after one’s self will only be effective when risks are relatively few. The rugged individualism promoted by US President Herbert Hoover in the late 1920s was shown to be wrong only a year later when recovery from the Great Depression required government intervention. In this sense, it was changes to governance and law which triggered an economic turnaround, even if these changes were opposed on ideological grounds by those who most benefitted from the previous regime. Social resilience, then, is ‘the capacity of groups of people bound together in an organization, class, racial group, community or nation to sustain and advance their well-being in the face of challenges to it’ (Reference Hall and LamontHall and Lamont, 2013: 2).

This shift to the social is the step we need to understand resilience across systems, though it runs the risk of making the same error that many psychologists have made – which is to focus on one level and exclude others. For example, we now know that badly traumatised people who have experienced social marginalisation or exposure to domestic violence may be genetically altered by these experiences or become neurologically susceptible if future stress occurs. Excessive burden on biological, psychological and social systems at the same time (what has been termed ‘allostatic load’ [Reference Hobfoll and FolkmanHobfoll, 2011]) compromises our ability to function socially and participate in community processes, including good governance and possibly legal proceedings. Though these connections across systems are still more conjecture than fact, a case can be built through a review of the biological, psychological and social systems literature that risk and resilience at any one system level will compromise or be advantageous to other systems at other levels. For these reasons, just as the psychological scientist needs to understand the social environment, those studying the influence of legal systems and other institutions need to appreciate the biological and psychological factors that inhibit healthy responses to social processes that are in the perceived best interest of individuals.

The experience of Rwandans before, during and after the genocide demonstrates patterns of resilience as a process occurring simultaneously at multiple levels (see also Chapter 4). Changes to a distal factor, like national policies on race, have influenced proximal systems, like peer relationships and even intransigent psychological systems related to an individual’s co-construction of personal identity. If these interrelated systems are to demonstrate resilience, whether that is recovery to a stable prior state or transformation to a new status quo, there needs to be some understanding of the mechanisms by which a change that makes one system function optimally improves the functioning of other systems as well. This may explain why Sinalo (2018) found that Rwandan men, post-genocide, tended to report a far greater sense of collective responsibility and move away from warriorship, while women shifted from thinking about themselves as ‘we’ (symbolising communion) and more as ‘I’ (symbolising greater agency and a focus on personal identity).

Of course, these ideological shifts came at a terrible price: the mass destruction and mutilation of lives. From the point of view of the study of resilience, however, such transformations suggest that processes of change look very different in different contexts. Just as trauma has been plagued by a Eurocentric bias in how it is understood and treated by the institutions tasked with responding, so too is resilience theory biased by Eurocentric notions of a shortlist of factors that promote well-being under stress that are popular in psychology. It is far better to imagine many different patterns to resilience across many different systems, from identity and gender relations to government structures, cultural practices and conflict resolution (including those that are part of transitional justice).

It is now recognised that, within different disciplines, there are generalisable principles that govern processes of resilience (for a review, see Reference Biggs, Schlüter, Biggs, Bohensky, BurnSilver, Cundill, Dakos, Daw, Evans, Kotschy, Leitch, Meek, Quinlan, Raudsepp-Hearne, Robards, Schoon, Schultz and WestBiggs et al., 2012; Reference UngarUngar, 2018). Among the most important are that resilience occurs in contexts of adversity where exposure to atypical stressors occurs and is a process that is influenced by how well people and resources interact. For this reason, I define resilience as the process through which individuals and groups navigate their way to the many different resources they need to sustain themselves and thrive, as well as the processes that systems use to negotiate for the resources that are most meaningful (Reference UngarUngar, 2011). The dual concepts of navigation and negotiation that are at the core of this social–ecological description of resilience underline the need to think about the individual’s environment and culture just as much as individual strengths and traits. To navigate does not mean individual motivation or personal agency; it implicates systems at other levels to provide the resources to individuals to support optimal functioning. Likewise, these resources must be those that the individual is able to negotiate for, so that they are provided in ways that match the individual’s belief systems or physical needs. The process is more circular than linear, with systems influencing what the individual values and needs, while individuals place demands on systems to provide novel resources as values change. In other words, individuals are not wholly autonomous in deciding which resources they need or how these resources will be provided.

For example, in research currently underway with two communities dependent upon the oil and gas industry as their major employer, my colleagues and I are documenting competing discourses concerning the resilience of these communities (Reference Mahdiani, Höltge, Theron and UngarMahdiani et al., 2020). On the one hand, community leaders and vested government interests insist on the persistence of the oil and gas industry, maintaining that it should be supported through taxation policies that preserve the industry as it is, including abolishing requirements for more fuel-efficient cars and building pipelines to get more products to market. These individuals argue fervently that they and their livelihoods are being treated unfairly and that any changes to the economic viability of their communities should be resisted. For them, their jobs and way of life are a matter of human rights.

On the other hand, there are those who perceive a rapidly approaching turn towards a zero-carbon economy and a need to dramatically decrease the production of petrochemical products. This group argues that the resilience of oil- and gas-dependent communities lies in their ability to quickly diversify their economy away from oil and gas extraction and production. For this group, the end to oil and gas production is an issue of environmental justice, though they are willing to compensate communities being affected by these changes with financial help during the transitional period. A compromise ideology supports a transformation but believes a slower period of change is required. Instituting a carbon tax, building pipelines and investing in cleaner technologies to extract and use oil and gas could give these communities the resources and time they need to adapt to a changing economy that is a response to climate change. All three processes are ways of dealing with an environmental crisis, but each reflects different patterns of navigation and negotiation for the resources that these communities value during periods of economic downturn and different definitions of what they perceive as just.

While this example is about economics and politics, it is also illustrative of how communities make themselves more resilient by changing multiple systems at once. Among those being displaced by the downturn in the oil and gas industry, there are feelings that their right to employment is being sacrificed by federal government policies and special interest groups that see these workers as expendable. These socio-economic changes also threaten individual mental health, as well as the social cohesion of the community itself. Seeking justice in the form of human rights and economic self-determination, however, has meant mostly resisting change, rather than establishing new institutional supports or arguing for compensation for retraining, relocation or economic diversification (all possible strategies for resilience).

On the other side of the debate, those who support the downturn see the closing of the industry as a means to achieve environmental justice. Viewed in this way, the factors that predict resilience will depend on which systems we want to sustain and which outcomes are preferred and by whom. As the case examples throughout this volume show, communities experiencing and engaging with transitional justice are heterogeneous, and myriad views on what constitutes ‘justice’ necessarily exist. Finding ways to build individual and social capital that different stakeholders experience as just, and therefore as a source of resilience, is a major challenge and one that requires local communities to have a say over the processes that they engage in.

The notion of resilience as a process is often misunderstood, particularly when researchers describe individuals, communities and governments as ‘resilient’. The preferred description is that these systems ‘show resilience’, meaning that they are in a process whereby they are able to take advantage of opportunities to improve their functioning. The issue is more than semantic. At the core of this ontological debate is the need to focus on what systems do to function better rather than their intrinsic qualities. Intrinsic qualities may never be realised if oppressive forces are beyond the capacity of the individual to change, with the result that resilience is reserved for the exceptional few who overcome the barriers around them. These processes, however, need not always be externally focused. As treatises on the resilience of the human spirit attest (see, e.g., Reference BeahBeah, 2007; Reference WestoverWestover, 2018; Reference WieselWiesel, 1956), reflective processes or belief in a special connection with one’s culture, God or ancestors have the power to carry us through periods of darkness. Even these responses to social injustice, however, should not be described as static traits of individuals. These are characteristics that are dormant until activated through processes that make them meaningful to the individual. In other words, resilience is always a process of realising the potential of systems.

The process of resilience is not, however, uniform. There are at least five patterns well documented in the literature (Reference UngarUngar, 2018), and each pattern is influenced by the qualities of the system under stress, human and social capital and by the economic and environmental resources available. These patterns of resilience include persistence, resistance, recovery, adaptation and transformation. A review of these patterns shows remarkable synergy between processes associated with resilience and the intent of processes and practices related to transitional justice, as other chapters in this volume demonstrate.

Persistence

A system shows persistence despite exposure to atypical stress when it maintains its functioning as a consequence of other systems sheltering the vulnerable system from harm. The system may appear to be resting or stable, but the effect is an illusion caused by its isolation or protection against outside threats that mitigate the need for reorganisation. Examples include traditional societies that are protected from outsiders like Brazil’s Kawahiva. Their precarious resilience and fragile experience of environmental justice are evident in the persistence of their culture and traditional lifestyle, but that persistence is a reflection of the efficacy of institutionalised laws imposed on outsiders through government processes at a scale quite separate from the community itself. Though these efforts have largely come too late and without sufficient enforcement to ensure the safety of the Kawahiva, their experience shows that resilience depends on external forces far more than individual qualities when populations face a threat like genocide or the destruction of the natural environment upon which they depend. To some extent, the same patterns are found among Amish peoples in North America, where tolerance by the cultural majority has been institutionalised so that the Amish can maintain their traditional way of life with minimal compliance with external rules (e.g., they still pay income tax, and children must still receive an education at least until the eighth grade). As these examples illustrate, legal systems can make it more or less feasible for communities to persist with behaviours that are viewed as non-normative by cultural outsiders.

Resistance

Resistance refers to a process whereby an individual, community or institution is under threat but is not sufficiently protected by outsiders to maintain its functioning. In this case, the system that is threatened must mobilise resources on its own to actively resist encroachment and maintain its right to be unique. Resistance is often a reflection of a lack of formal legal protection or of the need to adapt systems that are supposed to support human rights to account for differences. Indigenous peoples in countries like Canada and Australia, who have suffered past (and, arguably, ongoing) genocidal practices perpetrated against them, have lacked the social or legal protections to experience resilience (Reference Atallah, Contreras Painemal, Albornoz, Salgado and Pilquil LizamaAtallah et al., 2018). Instead, patterns of resistance have emerged where groups have become political in their efforts to secure their rights. Only recently have changes at the local level been reflected in changes at regional, national and international levels, with documents such as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples encouraging the protections and access to resources required for Indigenous communities to experience resilience. Where resistance occurs as a strategy for resilience, there are usually competing discourses regarding what is and is not a success, with different interests defining preferred outcomes. The process of resistance has the added advantage, however, of mobilising new resources when a system is under threat – resources that may create stronger systems as a consequence (e.g., a return to a community’s traditional cultural practices). Resistance may also change other contingent systems such as national bureaucracies or policing services. For example, institutionalised forms of racism against Indigenous peoples are still extremely prevalent but are being challenged to ensure better services and respect for human rights (Reference BlackstockBlackstock, 2016). In such cases, transitional justice initiatives like TRCs or honouring victims through memorials and reparations programmes can validate efforts to resist further threats to a population’s well-being.

Recovery

The concept of recovery is ontologically problematic as systems never ‘bounce back’ (Reference ZolliZolli, 2012) to their previous state but instead are changed by the experience of dealing with stress. Usually, this return to functioning reflects some nuanced change to the system’s behavioural regime, making it possible for the system to learn from past challenges and integrate what is learned. If a system returns to its previous role and appears to be doing the same thing it did before, it may even look recovered if small adaptations and transformations have occurred (see below). By way of illustration, recovery efforts after Hurricane Katrina on the southern coast of the United States seemed to signal a return by communities, like New Orleans, to previous levels of economic functioning and the resettlement of people to areas that were flooded. A closer look, however, shows changes to how new homes are being built (Reference Cutter, Emrich, Mitchell, Piegorsch, Smith and WeberCutter et al., 2014) and changes to practices during disasters to address racial inequalities experienced by minorities, though these changes have yet to be widely adopted (Reference Gotham and CampanellaGotham and Campanella, 2013).

Adaptation

When systems experience a stressor and are changed as a consequence, adaptation occurs. Where recovery returns a system to a former regime of behaviour, adaptation produces a novel set of processes designed to deal with the stressor now and into the future. The focal system changes so that it can survive. This adaptation, however, is not simply change at one systemic level. Typically, adaptation requires changes at multiple levels for the adaptation to be sustainable. For example, when urban planners allow (or encourage) the gentrification of inner-city communities, the results are often disastrous for the residents who were already living there. Adaptation may mean preserving these communities during a period of rapid change by building subsidised housing or ensuring services for those who are displaced. These adaptations are seldom satisfactory to the individuals displaced, though they work better at decreasing the largely negative impact on displaced residents when multiple levels of government, social services and community organisations work together to develop solutions to maintain the continuity of a community. In an example like this, persistence was likely never an option (there was no benign government looking out for the community) as the economic pressures on the community and rising housing costs would be beyond the capacity of any single level of government to prevent. Nor was resistance likely sufficient to oppose redevelopment. Recovery is nonsensical as it is unreasonable to expect a community with widespread poverty to return to that state after gentrification has started, even if the community seeks to preserve its unique identity. Adaptation, then, implies a ‘messy set of interactions occurring simultaneously across multiple systems at multiple scales’ (Reference UngarUngar, 2018: 34) and may be the best choice when there are few other available options. It can also implicate informal and formal justice systems through forms of remediation or protection of rights (e.g., the right to return to the community once new housing is built), though the process of adaptation seldom challenges the fundamental legal principles which cause people to experience injustice and exclusion.

Transformation

When human systems are exposed to stressors beyond their capacity to cope, transformation in how a system maintains itself is an ideal solution that implicates multiple systems in the development of new and sustainable regimes of behaviour that alter both individuals and their environments. Although one of the expressed aims of transitional justice and its many different forms is to seed such social transformation, the case examples in this volume highlight the multiple challenges that this entails across different systems. Transitional justice does contribute to processes leading to peace and reconciliation, which can result in structural changes to society at large. However, more often the changes that occur are modest in scale. Individual experiences – for example, of testifying in court – may increase individual resilience, but it remains unclear if they are catalysts for larger social transformations. Instead, the pathways to these transformations seem less direct, with small incremental changes in individual cognitions, social interactions and experiences of justice accumulating over time. Such adaptations leave the environment around the individual or system unchanged and the likelihood of another catastrophic challenge occurring in the future. Transformation, meanwhile, seeks change to the surrounding systems to avoid future exposure to stress. At the macro level, legislative systems play an obvious role in creating transformations that make other systems more resilient.

For example, the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 in the United States changed regulations for coal-fired power-generating stations that helped to protect lakes across North America from the impact of acid rain. Advocates for these imperilled ecosystems sought fundamental transformation in how power plants operated to prevent further devastation. A similar pattern of transformation can be seen in the dismantling of Apartheid in South Africa (though many of the problems that were synonymous with Apartheid continue today) and the relatively peaceful change of government that resulted. In each example, there is evidence of multiple human, institutional and even natural systems being transformed in response to changes at different systemic levels. To the extent that transitional justice processes contribute to these changes, the more likely they are to foster long-term resilience of multiple personal, social and environmental systems.

Dynamic Resilience: Equifinality, Multifinality and Differential Impact

Each of the five processes of resilience that were described above produce a number of different outcomes depending on the population affected and the environment that surrounds them. In general, however, the benefits of resilience are not shared equally, with different systems benefitting more or less from the change process. A number of concepts appear in the resilience literature to explain these different patterns and outcomes, among them equifinality, multifinality and differential impact. All three concepts are also relevant to the many forms of transitional justice.

Equifinality refers to various means to achieve a single desirable end. Studies of resilience tend to focus on equifinality and define a limited number of outcomes as positive aspects of change and development. When context is controlled, and homogeneity among actors and environments assumed, then the link between risk exposure, protective process and desired outcome is easier to describe. This simplified model, however, can suffer from the myopia that accompanies de-contextualisation, especially when cultural minorities and populations from low- and middle-income countries are the focus of the work. In the case of establishing peace post-conflict, or environmental justice for a community affected by rising sea levels due to climate change, the end goal may appear obvious (peaceful co-existence; a built environment that is sustainable), though the pathways to achieve these ends can still be many.

The various goals associated with transitional justice, for example, have an extensive desirability yet can look very different in different contexts, as this volume shows. As an illustration, one could debate the advantages and disadvantages of centralised power and authoritarianism in contexts where there has been a breakdown of social order and no history of democratic institutions. In such cases, an effective government may look very different during a period of transformation, while becoming dysfunctional and making a country vulnerable to future violence when it becomes institutionalised as a totalitarian regime (e.g., an elected president becomes president for life). It is common in studies of resilience to see a common set of outcomes defined for specific systems, with multiple strategies to achieve that end.

In contrast, multifinality is typical of systems that are adaptive and complex, especially when their resilience is being studied across cultures and contexts where there has been very little previous research. In these cases, there may be multiple desirable outcomes that are negotiated between local and state actors. Resilience-promoting processes may not be obvious to cultural outsiders whose Eurocentricity (or other social location) privileges one set of behaviours over another. To illustrate, women’s and men’s gender-normative behaviour can be responsive to changing economic and social conditions, making family systems more resilient. In the Philippines, for example, many women have found employment overseas as domestic workers, leaving their male partners to look after children and assume more household duties, tasks not typically taken on by men (these patterns can be disrupted when a grandmother is available to assume the role of primary caregiver for the children; see Reference ParreñasParreñas, 2000). Similarly, in Senegal, the large number of men who have migrated to Europe for work has resulted in women assuming men’s work despite the stigma of doing so (Reference SearceySearcey, 2019). In both examples, the assumption of non-traditional gender roles makes families and communities more resilient, but each context shapes which pattern of behaviour is preferred.

As these examples show, there are many similarities between the concept of multifinality as applied to resilience and Reference de Coningde Coning’s (2018) description of adaptive peacebuilding – a central concept that runs throughout this book (see also Chapter 11, this volume). de Coning challenges the idea that there is one right outcome from peacebuilding, and indeed honours multiple cultural traditions as potentially positive sources of inspiration for ways to recreate social cohesion and stability after a period of violence. As Reference de Coningde Coning (2018: 304) writes, adaptive peacebuilding:

[R]ejects the liberal peace theory of change – namely, that an external peacebuilding intervention can set in motion and control a causal sequence of events that will result in a sustainable peace outcome. In its place, it argues that the role of the UN is to assist countries to sustain their own peace processes by strengthening the resilience of local social institutions, and by investing in social cohesion.

The concept of multifinality simply describes this pattern of sensitivity to context and flexible outcomes as common to many different systems when they operate in complex environments. To understand resilience, however, one must also account for the nature of both those doing the navigation and negotiation and the environment in which it occurs. In the field of human biology, an emerging concept of differential susceptibility has shown that depending on one’s genes or other traits, interventions will have a different impact on individual change (Reference Belsky and van IjzendoornBelsky and van Ijzendoorn, 2015). Susceptibility implies individual responsibility for change with personal qualities determining which environmental trigger is most useful for personal success. Differential impact switches the focus to the quality of the environmental trigger, something which is far more malleable than individual qualities like one’s genome (Reference UngarUngar, 2017). When examining the differential impact of an intervention, social policy or legal system, one asks, ‘Which population, at what level of risk, is likely to most benefit from this support?’ The question challenges us to consider how different kinds of support produce resilience in highly stressed environments and how each is tailored to the needs of populations with specific profiles.

When interventions underperform or fail to produce desired changes in behaviour, the responsibility for the lack of success is attributed to the intervention, not the individual. The concept of differential impact, then, opens possibilities for understanding why some interventions may work better in some contexts and cultures than others (Reference Birgden, Arrigo and WardBirgden et al., 2015). It is the dynamic fit between interventions and individuals that is critical. Because the model is adaptive, it is not uncommon to see the same intervention having a positive effect with one population and a deleterious effect with another, or a small impact with one and a very large impact with another. Designing interventions to promote resilience of any system requires that attention is paid not only to the end goal but also to the quality of the interactions between those needing help and those providing it.

Making Justice Systems Resilient

The advantage of transitional justice and its many variations is that it has the potential to offer formal legal systems the means to adapt to changing demands by those using them, especially in contexts where legislated systems have largely failed to maintain peace and need to recover and show resilience. Reference Ruhl, Cosens, Soininen and UngarRuhl et al. (2021) describe formal legal systems as themselves needing this resilience if they are to be sustainable. That sustainability and effective functioning means that both formal and informal systems of accountability, whether from the courts or community talking circles, can also influence the resilience of other co-occurring systems. Reference Ruhl, Cosens, Soininen and UngarRuhl et al. (2021: 510) write: ‘Resilience in legal systems is, thus, often used to facilitate normative social purposes fulfilled through other social systems.’ For Reference Ruhl, Cosens, Soininen and UngarRuhl et al. (2021: 511), legal systems are complex, meaning that they have many interrelated parts which together form ‘a large network of components with no central control and simple rules of operation giving rise to complex collective behavior, sophisticated information processing, and adaptation via learning or evolution’.

This complexity, which is also a fundamental dimension of adaptive peacebuilding (see de Coning, Chapter 11), means that legal systems are able to respond to, or look different in, different contexts. Transitional justice processes can help them to become more responsive by broadening the definition of what constitutes a legal system to include the many ways that societies support economic and human rights, land rights and environmental justice. This means, for example, integrating cultural and/or Indigenous practices where appropriate, or using combinations of formal codified legal institutions like courts and legislation, community justice forums, collaborative law practices and other means to achieve transitional justice. These practices require many and varied systems to co-exist, though which system is needed and when will depend on the conditions in which they operate and on competing discourses of justice expressed by those whose rights have been transgressed.

These tensions are obvious in contexts like fly-in courts in the Canadian Arctic, which serve the needs of mostly Indigenous communities. In that context, the judiciary uses both formal and community-based legal mechanisms to maintain the social cohesion of communities and facilitate the reintegration of offenders. While these efforts are noteworthy, they are also controversial with some perceiving the sentencing of offenders (e.g., perpetrators of domestic violence) as too lenient to act as a deterrent (Reference RudinRudin, 2018).

Despite these difficulties, systems that promote transitional justice or the enforcement of laws and still show resilience when strained are typically those that are adaptive (Reference Murray, Webb and WheatleyMurray et al., 2019), are moving away from an exclusive focus on the individual’s responsibility for a problem and are becoming more adept at interpreting crime in ways that account for the social contexts of offenders and their past experiences of trauma (drug courts are a well-studied example; Reference Latimer, Morton-Bourgon and ChrétienLatimer et al., 2006). Thus, we are seeing a move away from the neoliberalism that characterised earlier resilience research. The earliest efforts to study resilience documented the exceptional few who did better than expected, and implied that their success could be reproduced if better understood. This initial work, however, was badly flawed, mostly because of its decontextualisation. It failed to account for different amounts of privilege and barriers to optimal human development, including access to justice. Many marginalised communities rejected resilience as a consequence, seeing it as an excuse for blaming victims of oppression who did not manage to ‘beat the odds’.

Fortunately, a shift has occurred in how resilience is understood, a conceptualisation that is much closer to the way peacebuilding is now undertaken. Where we once imagined peace as an end state, a trait of a community that was no longer at war, peace and justice are now understood as processes that are a ‘more open-ended or goal-free approach towards peacebuilding, where the focus is on the means or process, and the end-state is open to context-specific interpretations of peace’ (Reference de Coningde Coning, 2018: 301). It is this embrace of many good means to many good ends that makes resilience and efforts like transitional justice a good match.

Though all of this makes the resilience of legal systems and systems associated with transitional justice and peacebuilding seem unpredictable, these systems tend to reflect five principles when operating well. According to Reference Ruhl, Cosens, Soininen and UngarRuhl et al. (2021: 517), these include the following:

1. They are reliable. When one component fails, a justice system can still maintain its resilience and function properly despite an unanticipated (or anticipated) stressor. This, in turn, means that subsystems (such as individuals seeking compensation) maintain their belief (a system of cognitions and socially constructed values) in the institutions that govern and regulate their lives.

2. They are efficient. They are not overly burdened by swollen bureaucracies that make seeking justice interminable or excessively expensive. They appear accessible to the individuals needing to use formal and informal legal systems, and they promise expedient resolution of conflict. A justice system like this will encourage compliance and be more sustainable if people do not feel the need to turn to vigilantism or other forms of extra-judicial actions as when farmers arm themselves to protect their property from thieves.

3. They are scalable. As problems tend to affect multiple systems at multiple levels, a justice system that shows resilience will engage in processes across jurisdictions so that local processes that may appear less formal but instil a sense of fair treatment are not subsequently overturned by a court or other legislative body. For example, if a local restorative justice process resolves a criminal matter but the individual charged still faces sanctions beyond the community, the advantages of a resilient justice system at the local level quickly diminish.

4. They are modular. Justice systems show the most adaptability when there are multiple systems that can step in to resolve an issue should one system fail. In the case of environmental justice, where state governments in the United States have been lowering pollution standards to remain competitive for investment and jobs, it has taken the federal government to establish laws that are in the best interest of the country as a whole. The reverse is also true; when the federal government abdicates its responsibility to tackle challenges like climate change, it is state governments that have stepped in to press forward with legislation in areas like tailpipe emission standards (Reference VogelVogel, 2018).

5. They evolve. Justice systems show resilience when they change as social contexts and natural environments put pressure on human systems. While not all justice systems need to evolve (national constitutions are meant to resist the vagaries of changing governments), laws and legal practices need to be malleable to respond to the exigencies of emerging crises, whether that is the mass migration of undocumented refugees or the need for adaptive peacebuilding efforts at a local or national level. Justice systems are most resilient when they embrace this tension between their ability to change and their need for stability over time.

Together, these five principles reflect much of what we know about resilience-promoting processes and the way justice systems like transitional justice or adaptive peacebuilding support adaptation and transformation when individuals and communities are placed under stress.

The Need for a Better Understanding of Justice Systems and Resilience

Unfortunately, there has been limited research on resilience that is sufficiently complex to capture the interactions between systems at different scales. In practice, this means that we may study individual trauma and coping strategies but not investigate whether the quality or quantity of trauma confounds the efficacy of a transitional justice initiative, or for that matter whether cultural norms and indigeneity influence the reliability of formal legal systems in contexts of extreme poverty. Where such questions do arise, protective mechanisms tend to be studied at a single scale, while risk factors like coloniality are homogenised and controlled as a simple variable that is thought to affect everyone equally. The emerging science of resilience is changing this. It is showing the need to think about complex, interacting systems and how to best account for the relationship between risk exposure, protective processes (resilience) and outcomes across multiple systems at once.

In practice, this means understanding why communities might or might not work together to preserve a natural resource given past histories of collective trauma, gender norms, economic conditions, trust in government (and each other), identity and confidence in legal systems. The following brief case examples illustrate the need for multiple systems to show resilience if new regimes of peace and security are to result. The first example shows what can happen when there are no available means for economic or social justice, while the second example illustrates what happens when residents in a community under stress are treated more fairly and in ways that support both social and environmental justice.

Embalenhle

The South African township of Embalenhle is within sight of one of the world’s largest petrochemical processing plants operated by the state-owned corporation SASOL. With over 100,000 inhabitants, many of them economic migrants, Embalenhle is a chaotic mix of permanent homes, government-built shelters and informal tin-roofed shacks crisscrossed by a river choked with rubbish. The streets are dangerous, the schools woefully underfunded and in bad repair. SASOL, through a programme of corporate social responsibility, funds initiatives like libraries, sports centres and even public infrastructure like roads and sidewalks. Unfortunately, the level of mismanagement at the local and national government levels and people’s general frustration with their social and economic marginalisation have resulted in frequent outbreaks of violence by residents, targeting municipal offices, the local mall and even the rubbish trucks that were meant to pick up the refuse (but were inefficient at the task).

In this environment, children make educational decisions that focus on securing work at the plant, choosing science courses whenever possible. Beyond the structural challenges, the local population deals with violence in the streets, high rates of substance abuse and the lack of family cohesion as one or both biological parents leave to find employment elsewhere. In this context, there is a general breakdown of social order, with elections fraught with violence and a general malaise when it comes to believing that institutional actors will make things better. Corruption creates daily hassles, with even sitting an entrance exam to a local college requiring a bribe. The police are perceived as exploitive and a threat.

Though South Africa is a society that holds collectivist values, young people have adopted a more competitive attitude when interacting with others beyond their families. In this context where fair treatment is perceived as unattainable, there are few opportunities for resilience to occur, or for formal and informal justice systems to be perceived as trustworthy and supportive. Psychological trauma, threats to physical health (including pollution), inadequacies of the educational system and a lack of government or legal institutions that function optimally have left the population largely unable to move forward. The few individuals that do succeed do so as a consequence of exceptional talent or personality traits, rather than institutional supports available equally to all. At this time, there are very few ways for community members to experience economic justice or respect for their human rights within or beyond the institutions regulating their lives.

Ruhengeri

This is a community adjacent to the Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda and part of a three-nation protected area that is home to the endangered mountain gorilla. At risk of extinction a decade ago, the population of gorillas has more than doubled to more than 1,000 animals. Both human encroachment on habitat and poaching have been stopped, in large part by strict enforcement of laws and a paramilitary force that protects the gorillas. All of this has been a deliberate plan to ensure communities closest to the park benefit from the efforts to protect the animals, reflecting a form of environmental justice in which those whose lands are being used benefit from their use. In the case of Ruhengeri, a percentage of the money paid by tourists to trek and view the gorillas is used for community development across the region. Locals are hired as guides and porters, rangers and security forces. There is also a growing network of hotels, as well as work for drivers and others involved in the tourism industry. While it is debatable whether this kind of development, which caters to the very wealthy from other countries, is beneficial to Rwanda, and whether it spurs sustainable growth, the government has proceeded with this approach. The result is some obvious economic benefits to the local population and an even bigger positive impact on the mountain gorilla’s ecosystem.

To understand the resilience of a community like this, one needs a theory of change that accounts for what is occurring rather than one that describes static outcomes (Reference Valters, Cummings and NixonValters et al., 2016). As conditions have changed for people, and with recognition for their histories, culture and context, which include the recent experience of genocide, structural inequality, colonisation and lack of environmental justice, one sees that the right solution for resilience has to be carefully adapted and implemented (no such efforts for justice other than popular uprisings are in evidence in Embalenhle). Even though success is possible, there is a level of uncertainty as complex personal, social and institutional systems respond to pressing challenges like environmental and economic justice. This means that resilience, like processes of transitional justice, must be responsive to previous risk exposures and local exigencies, but it must also be driven by adherence to principles that make the model useable even if outcomes vary. Thus, one community’s solution to poaching and environmental injustice post-conflict is unlikely to suit another if historical and economic conditions and incentives are different. As Reference de Coningde Coning (2018) explains, there needs to be a shift from a focus on ends (and their replication) to means (and their nuanced adaptation to context).

Conclusion

The concept of resilience is gaining traction in the discourse surrounding concepts like justice and peacebuilding, though it is not yet widely understood. When applied, the term ‘resilience’ refers to the capacity of individuals to succeed because internal and external systems work together to help people achieve their potential. Resilience also includes the capacity of these systems (including systems of justice) to demonstrate robustness and cohesion with other systems to maintain themselves, despite social and economic disruptions or natural disasters. There are multiple processes that produce resilience, depending on the environment in which individuals, communities and institutions are struggling to cope. Whether a system persists, resists, recovers, adapts or transforms is a reflection of the resources available and the discourses that define success. Protective and promotive processes need not be focused on a single end, nor can we predict with certainty how a change in intervention, public policy or transitional justice process is going to affect all members of a community. Resilience is, however, a concept that describes complex series of interactions across multiple systems and at different scales. To the extent that transitional justice, peacebuilding and legal mechanisms are adaptive and flexible with regards to the goals that they seek to achieve, the more likely resilience is to be experienced by individuals and their communities.

This chapter reflects on the implications of resilience thinking for transitional justice as a transformative process that contributes to adaptive peacebuilding. Recognising that resilience is highly relevant to a number of core transitional justice goals, including the re-establishment of the rule of law, peace and reconciliation, it discusses how the concept creates a space for new thinking about transitional justice. In so doing, it explores the extent to which transitional justice processes affect and engage with multiple interacting systems in ways that can foster resilience and adaptive capacity across these systems and the relationships that underpin them.

The chapter examines how each of the primary state-based mechanisms of transitional justice – namely, criminal trials, truth commissions and reparations – might contribute to systemic societal resilience, notwithstanding their limitations, and discusses their potential for healing divisions and building relationships to support resilient social structures. It also considers how more community-driven facilitated justice processes, including traditional customary practices and psychosocial programmes, can expand the basis for building resilient communities and systems.

As part of this analysis, the chapter provides a critical appraisal of the overall approach to transitional justice that has dominated the field, considering transformative justice as an alternative perspective that challenges a politico-legal, state-based, backward-looking retributive framework. It argues that resilience thinking supports a greater focus on psychosocial, community-based, forward-looking restorative approaches to transitional justice, consistent with the transformative turn in the field (Reference Gready and RobinsGready and Robins, 2014; Reference Lambourne, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and MiethLambourne, 2014a). This is demonstrated by exploring different understandings of justice, how they are pursued in the context of transitional justice and what they mean for building resilient societies after mass violence and human rights violations. The chapter concludes by reflecting on the potential for a transformative approach to transitional justice consistent with building resilience to support adaptive peacebuilding in practice.

Understanding Transitional Justice and Types of Justice

Transitional justice can be defined as a process intended to provide justice for mass human rights violations committed in the context of war or a past autocratic regime. The idea of ‘transition’ is key – from a past where human rights were violated with impunity to a future characterised by democracy and the rule of law, which, in turn, is assumed to lead to the protection of human rights (International Center for Transitional Justice, 2001). In the context of post-war transitions, the goals of transitional justice are more explicitly linked to peacebuilding, going beyond democracy and the rule of law to the pursuit of truth, reconciliation and institutional reform (United Nations [UN], 2004).

However, in some cases, transitional justice processes are also implemented in periods of non-transition, where justice is sought for ongoing mass human rights violations or where the regime that committed the violations in the past is still in place. Reference WinterWinter (2014), moreover, argues for a political theory of transitional justice that applies to the context of authorised wrongdoings by established democracies (such as those perpetrated against Japanese Americans during World War II). Transitional justice thinking has therefore been applied to situations of ongoing colonial and post-colonial oppression, including the treatment of Indigenous peoples by settler societies, such as in Canada where a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) on Indian residential schools was established in 2008 (Reference NagyNagy, 2013; Reference NiezenNiezen, 2013).

What transitional justice might look like thus varies across different settings. There might be a focus on retributive justice to punish those accused of committing mass atrocities as a means of ensuring non-repetition, as highlighted by the example of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). Alternatively, the main priority might be restorative justice and/or reconciliation, with the aim of healing individuals and rebuilding relationships and communities; the TRC set up in post-apartheid South Africa is just one example. Some transitional processes involve a combination of both retributive and restorative justice. In Sierra Leone, a Special Court and a TRC operated alongside each other; and in Rwanda, the traditional gacaca community justice process (see Chapter 4) that combined retributive and restorative justice aims was adapted to deal with the crimes of the genocide.

Reparative justice, another key approach to justice, seeks to repair the damage of the past through measures such as payment of compensation to victims or collective reparations in the form of projects to benefit the community. An example of reparative justice is the moral reparations pursued in the framework of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) in relation to human rights violations committed by the Khmer Rouge regime (see Chapter 7). Reference TeitelTeitel (2000: 119) lists a number of measures that can be classified as contributing to what she calls reparatory justice, including reparations, damages, remedies, redress, restitution, compensation, rehabilitation and tribute.

With a more forward-oriented focus, distributive or socio-economic justice has been identified as important for building a future that goes beyond protecting civil and political rights and also addresses cultural, social and economic rights (Reference Lambourne, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and MiethLambourne, 2014a; Reference ManiMani, 2002). This is consistent with building a ‘positive peace’ that addresses the root causes of conflict and promotes a more politically and socio-economically just future, rather than simply a ‘negative peace’ that seeks to end the direct violence of war and mass atrocities (Reference GaltungGaltung, 1969). Guatemala has been cited as an example where this approach was prioritised and where the pursuit of accountability for the crimes of former leaders existed alongside institutional and socio-economic provisions aimed at addressing the underlying causes of the conflict (Reference ManiMani, 2002: 165).

The term ‘historical justice’ is used to encompass situations where the focus is not on transition per se, but rather on seeking redress for historical wrongs that are transmitted across generations through collective memory and memory practices. Examples include abuses committed in the context of colonisation and human rights violations against Indigenous peoples (Reference Neumann and ThompsonNeumann and Thompson, 2015). Reference TeitelTeitel (2000) uses historical justice as a term to frame the need for truth – a need that is often the primary driver for the creation of different types of historical commissions or truth commissions as defined and examined in theory and practice by Reference HaynerHayner (2011). The pursuit of the truth in the form of an account of historical wrongdoings is frequently combined with a restorative or reconciliatory focus in the form of a TRC as a particular form of truth commission (Reference HaynerHayner, 2011: 12). The aforementioned TRCs in South Africa and Canada are two such examples that focused on revealing the truth and promoting reconciliation for past wrongs. Additionally, the concept of historical justice goes beyond the idea of individual criminal justice to recognise the need for collective forms of accountability to match the collective nature of the crimes committed (Reference TeitelTeitel, 2000: 75). This may take the form of political justice or rectificatory or corrective justice (Reference Butt, Neumann and ThompsonButt, 2015: 171).

Transitional Justice and Peacebuilding

Notwithstanding the range of approaches to justice outlined above, transitional justice in practice has often been limited to a legal retributive approach, especially where practitioners follow the model of transitional justice promulgated by the UN (2004, 2010). Transitional justice, as part of a post-conflict peacebuilding agenda, has been pursued by the UN based on a ‘one-size-fits-all’ model of liberal democratic reforms and mechanisms designed to support individual accountability and the rule of law. The perception of a duty to prosecute in international law, as espoused by Reference OrentlicherOrentlicher (1997, Reference Orentlicher2007), has manifested in a commitment to international criminal justice as the primary means of implementing transitional justice – what Reference DrumblDrumbl (2002: 8) has described as the ‘hegemonic imperative to implement criminal trials’ and Reference SikkinkSikkink (2011) later characterised as the ‘justice cascade’.

Under international criminal law, criminal responsibility is assigned to individuals for particularly serious violations of human rights defined in international law as war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide (sometimes grouped together as mass atrocity crimes). These international mass atrocity crimes can be prosecuted in international, hybrid (a mixture of international and national laws) or regional courts, or in national courts where states have enacted domestic legislation to criminalise such violations of human rights and the laws of war. They can also be prosecuted under the provisions of universal jurisdiction.

Following the precedent of the post-World War II trials at Nuremberg and in Tokyo, the two ad hoc international criminal tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, respectively, were created by the UN Security Council in the early 1990s, when the freedoms of the end of the Cold War enabled agreement to be reached on such measures intended to restore international peace and security. International prosecutions have been pursued as part of transitional justice in order to provide accountability for past atrocities, build peace and prevent future atrocities through combating impunity and promoting justice, reconciliation and the rule of law, at least in theory, if not in practice (UN, 2004).

The ‘duty to prosecute’ was derived from the ‘right to justice’, which former French jurist and human rights defender Louis Joinet determined was one of four ‘Principles against Impunity’ in his famous report to the UN Human Rights Commission (UN, 1997). These four principles – namely, the right to know, the right to justice, the right to reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence – were translated into the UN’s four key pillars of transitional justice: prosecution initiatives, truth-seeking processes, reparation programmes and institutional reform (UN, 2010). In this politico-legal context, justice is assumed to mean legal justice in the form of prosecutions and punishment (i.e., retributive justice), which is intended to deter future war criminals and thus contribute to the fourth aforementioned principle of guarantees of non-recurrence. From this perspective, the future orientation of transitional justice is thus limited to rebuilding the rule of law and implementing institutional reform as a further means of ensuring non-repetition of past human rights violations.

However, while the ‘right to justice’ has been seen as paramount by the UN and other international actors, including the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), the ‘right to know’ through truth-seeking processes has also risen to prominence in the form of the truth commission (Reference HaynerHayner, 2011). The truth commission, like the criminal court or tribunal, is a mechanism representing a programmatic approach to transitional justice adopted by countries in order to deal with a history of past mass human rights violations, with or without the involvement of the international community. Originally associated with amnesties and the perpetuation of a culture of impunity, the early truth commissions of the 1990s were seen as representing a political compromise of revealing the truth in exchange for justice where ‘political resistance to accountability was high’ (Reference HaynerHayner, 2011: 91). A clear example of this is the case of El Salvador, where a blanket amnesty was passed into law following the release of the country’s truth commission report in 1993 (Reference HaynerHayner, 2011: 102). In other cases, de facto blanket amnesties would result when no formal transitional justice was pursued, such as in post-civil war Angola and Mozambique (Reference Olsen, Payne and ReiterOlsen et al., 2010: 40).

The South African TRC, with its innovative approach of providing individual conditional amnesty rather than blanket amnesty (Reference HaynerHayner, 2011: 29), challenged this perception of compromise between justice and truth. Its emphasis on restorative justice as an alternative form of justice took a more forward-looking approach, aimed at rebuilding a new ‘rainbow nation’ by transforming the relationship between black and white South Africans through healing, forgiveness and reconciliation (Reference TutuTutu, 1999: 51–52). The South African TRC also expanded notions of truth beyond victims’ right to know the factual and forensic truth of what happened, to their own narrative truths and personal stories of what happened to them. By providing a public space for the expression of these personal/narrative truths, the South African TRC was seen as facilitating the creation of a shared social or dialogical truth that contributed to an experience of restorative or healing truth, thus expanding the ‘right to know’ from a historical concept to a future-oriented process of healing and reconciliation (Reference Boraine, Boraine and ValentineBoraine, 2006).

As outlined by Reference HaynerHayner (2011), most truth commissions subsequently have called for prosecutions in their final report, and the use of amnesties has become less common, even though the political constraints on pursuing accountability have remained in such countries as Burundi and Sri Lanka, where truth commissions have been established but a culture of impunity prevails. In other cases, truth commissions have not precluded the pursuit of criminal prosecutions, as in post-civil war Sierra Leone (Reference Ainley, Friedman and MahonyAinley et al., 2015).

The ‘right to reparation’ has similarly undergone an evolution in transitional justice, from the original focus on seeking material compensation and payments to individuals through reparation programmes to a more pragmatic emphasis on the concept of moral or collective reparations, as illustrated by the example of the ECCC mentioned earlier. Reference Laplante, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and MiethLaplante (2014) offers a justice continuum model of reparations, which starts at the narrowest end with reparative justice linked to the classical tradition of corrective justice through civil remedies or material compensation for specific harms or losses, as pursued in a number of cases including Chile and Morocco. Next in the continuum is restorative justice, involving the participation of victims as stakeholders and a focus on restoring their dignity and local ownership in the reparations process, as seen in many traditional customary practices, such as the nahe biti process incorporated into the East Timorese Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR) (Reference Babo-SoaresBabo-Soares, 2004). This is followed by what Reference Laplante, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and MiethLaplante (2014: 74) identifies as a civic justice approach, which moves beyond the micro-level reconciliation inherent in the restorative justice approach to a focus on the macro-level relationship ‘between the government and the governed’ and the potential for political transformation, as seen in the Peruvian reparations programme. Finally, at the broadest end of the spectrum, socio-economic justice, according to Reference Laplante, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and MiethLaplante (2014: 77), provides the opportunity for reparations to ‘remedy historical social and economic inequalities’ and contribute to distributive justice that links directly to the goals of sustainable peacebuilding and transformative justice (Reference LambourneLambourne, 2009, Reference Lambourne, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and Mieth2014a), as discussed later in this chapter.

Despite developments in transitional justice focusing on broader understandings of truth, justice and reparations that are more consistent with building peace and reconciliation, they have remained secondary to the overriding imperative to pursue retributive justice and factual/forensic truth through criminal prosecutions as a means of fulfilling the ‘right to justice’ principle. There are, however, signs that this could be changing if transitional justice follows the same path as peacebuilding in its turn away from liberal democratic programmatic responses towards a more pragmatic approach associated with building local resilience to future crises (Reference ChandlerChandler, 2017; Reference de Coningde Coning, 2016; Reference Juncos and JosephJuncos and Joseph, 2020). As explained by Reference de Coningde Coning (2016: 167), this new focus on pragmatic peacebuilding:

… is shifting the debate away from liberal top-down problem-solving approaches towards more pluralistic bottom-up, or hybrid, conflict management approaches that do not have the ambition to resolve conflict, but instead invest in the resilience of local social institutions to prevent, cope with and recover from conflict, i.e. to sustain peace.

This so-called pragmatic turn in peacebuilding can be related to the ‘transformative turn’ in transitional justice, in which scholars have proposed alternative approaches to justice that go beyond those promulgated by the UN’s model of transitional justice with its emphasis on programmatic responses to support the four key pillars – prosecutions, truth, reparations and institutional reform. Accordingly, before moving to a discussion about the implications of different types of resilience thinking for transitional justice, the next section will first examine how notions of transformative justice have evolved to challenge the dominant politico-legal, prosecutorial approach to transitional justice.

The Transformative Turn in Transitional Justice

Reference DalyDaly (2002) first proposed the idea of transformative justice as a means of recognising the transformative agenda inherent in transitional justice and supporting the social transformation necessary to meet the goals of reconciliation and deterrence. According to her:

Simply changing the governors won’t cure a problem that resides as well in the governed. … This entails not just a transition, but rather a transformation. Transition suggests movement from one thing to another – from oppression to liberation, from oligarchy to democracy, from lawlessness to due process, from injustice to justice. Transformation, however, suggests that the thing that is moving from one place to another is itself changing as it proceeds through the transition; it can be thought of as radical change (Reference DalyDaly, 2002: 74).

As part of this transformative agenda, Reference DalyDaly (2002) proposed the need to consider other forms of response extending beyond retributive justice for individual harms to address different types of injustices – including collective economic or political injustices, as in South Africa. Reference LambourneLambourne (2009, Reference Lambourne, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and Mieth2014a) built on this idea of a transformative agenda to incorporate different types of justice in her model of transformative justice: legal (including both retributive and restorative) justice; socio-economic justice; political justice; and psychosocial justice and healing derived from truth, comprising both knowledge of what happened and acknowledgement that what happened was wrong.

Similar to Reference DalyDaly (2002: 92), Reference LambourneLambourne’s model (2009, Reference Lambourne, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and Mieth2014a) was predicated on the need for a transformation that goes beyond the narrow confines of a transitional moment to a more pervasive transformation of society that would respond to the priorities of a particular cultural and conflict context, consistent with Reference UngarUngar’s (2008) emphasis on the critical role of cultural context in determining levels of resilience in at-risk populations. More specifically, Lambourne’s model of transformative justice underlined that justice must be seen as more than transitional. It must set up structures, institutions and relationships to promote transformation and sustainability (Reference LambourneLambourne, 2009, Reference Lambourne, Buckley Zistel, Koloma Beck, Braun and Mieth2014a).