Introduction

In a parliamentary democracy, the power of parliament to oversee government activities is a key component ensuring the stability and legitimacy of the democratic system. To extract information about government action, monitor the execution of laws, and compel the government to defend decisions, individual legislators have considerable privileges (Mattson and Strøm, Reference Mattson, Strøm and Döring1995; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2000). Given their importance for the functioning of parliamentary democracy, legislative oversight instruments constitute a key research interest in the field of legislative studies. An extensive set of scholarly work explores the formal means that MPs (members of parliament) use to control government activity, such as written or oral questions to the government submitted by individual legislators or whole fractions (Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2000; Friedberg, Reference Friedberg2011; Martin, Reference Martin2011; Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Proksch and Slapin2013; Martin and Whitaker, Reference Martin and Whitaker2019). This research depicts a highly institutionalised process, with MPs who usually belong to opposition parties holding the government accountable (Franklin and Norton, Reference Franklin and Norton1993; Wiberg, Reference Wiberg1994; Akirav, Reference Akirav2011). However, the usage of oversight instruments is far from determined by government-opposition dynamics. For instance, even representatives belonging to governing parties submit questions, in particular in coalition governments (Martin and Whitaker, Reference Martin and Whitaker2019; Höhmann and Sieberer, Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020; Höhmann and Krauss, 2021). And even within the opposition, variation in the oversight activities of MPs is considerable. To give an example, opposition members in the Merkel I cabinet in Germany submitted on average 75.72 parliamentary questions, but the standardised deviation from this mean was 64.54, with observed values ranging between not a single and more than 400 questions. In this contribution, we engage with one potential explanation for such individual-level differences in legislative oversight activities: gender.Footnote 1 Differences in socialisation are well-known to create variation in the substantial priorities (Childs, Reference Childs2001; Bird, Reference Bird2005; Celis, Reference Celis2006; Frederick, Reference Frederick2009; Höhmann, Reference Höhmann2020) and policy-making styles of men and women in parliament (Cowley and Childs, Reference Cowley and Childs2003; Volden et al., Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013). However, to what degree the behaviour of MPs in highly institutionalised processes, such as legislative oversight, displays differences has not, as yet, received any scholarly attention. To address this research gap, this article engages with two questions: does the gender of MPs shape their legislative oversight activities? If so, how exactly?

We introduce the original argument that the oversight style of men and women is substantially different, with women asking more questions than men when in opposition and less questions than men when in government. Building on research from Social Psychology, we propose that this gendered behaviour originates in different behavioural expectations (Eagly and Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Heilman and Okimoto, Reference Heilman and Okimoto2007; Rudman et al., Reference Rudman, Moss-Racusin, Phelan and Nauts2012) as well as different levels of risk aversity between women and men (Jianakoplos and Bernasek, Reference Jianakoplos and Bernasek1998; Ertac and Gurdal, Reference Ertac and Gurdal2012; Nelson, Reference Nelson2015). For elected representatives, any action that threatens their re-election is risky including those that threaten the support of their party for re-nomination (Hix, Reference Hix2002). As risk-averse individuals, women should conform more strongly with the institutional roles their party expects them to play. Therefore, they should be more prone to show that they are critical opposition members who hold the government accountable – and less likely to keep tabs on their own party and coalition partners through formal oversight mechanisms when in government. This argument moves beyond the analysis of differences between men and women and the roles that have been ascribed to them via their gender. Rather it implies that gender differences shape perceptions of roles as members of the government and the opposition respectively.

We put these propositions under empirical scrutiny by studying the oversight activities of MPs in the German Bundestag between 1949 and 2013. Our analysis builds on a quantitative approach and investigates the frequency with which parliamentarians make use of three instruments for legislative oversight: Parliamentary questions, minor requests, and proposals. We exploit the panel structure of the data and study how MPs who move from government to opposition, or the other way around, adapt their behaviour. In this manner, we end up with findings about the way being in government or opposition impacts behavioural patterns of women and men that are not a consequence of other systematic differences between opposition and government members. To the best of our knowledge, this is a – so far – unique approach in the literature on the use of oversight mechanisms.

Our results have important implications for the field of legislative studies but also for democracy itself. First, to fully understand the functioning of the legislative oversight process, we need to consider the characteristics of the actors involved in this process. Even though previous research presents this phenomenon as a strongly institutionalised process close to being determined by government-opposition and coalition dynamics (Franklin and Norton, Reference Franklin and Norton1993; Wiberg, Reference Wiberg1994; Akirav, Reference Akirav2011; Martin and Whitaker, Reference Martin and Whitaker2019; Höhmann and Sieberer, Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020; Höhmann and Krauss, 2021), men and women behave differently. By taking into account how individual-level differences between MPs influence the interaction of government and parliament, we draw a more accurate picture of the functioning of legislative oversight in parliamentary democracies. Second, by revealing sex differences in legislative oversight activities, our findings add to a growing set of research uncovering additional barriers for women’s equal participation in parliamentary decision-making, e.g., in the form of higher levels of party discipline (see e.g., Cowley and Childs, Reference Cowley and Childs2003; Thames and Rybalko, Reference Thames and Rybalko2010; Clayton and Zetterberg, Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2021). Deviation from the behaviour of men, which is perceived as the norm in politics (Childs, Reference Childs2004; Galea and Gaweda, Reference Galea and Gaweda2018), could decrease women’s chances to be selected to more influential political posts by party leaders. Moreover, women in the opposition might invest more time into oversight activities than men, so that they have less time left to follow other political and policy endeavours.

This article proceeds as follows: we begin with presenting our theoretical argument about the influence of gender on MPs’ likelihood to conform with their institutional roles in the interplay of government and opposition. After that, we explain our research design and the operationalisation of our main dependent and independent variables. Our empirical section is divided into two parts: first, we present bivariate statistics about sex differences in role-conforming behaviour. Second, we run a multivariate error correction model (ECM) to test our hypothesis. Our findings broadly support our expectations: Men and women differ with regard to their role-conforming behaviour, with women changing their behaviour more strongly than men.

How institutional roles in the legislative oversight process are gendered

This article analyses the influence of gender on the level of conformity to institutional roles directly derived from the principal-agent theory (Strøm, Reference Strøm2000; Miller, Reference Miller2005). Applying the rationale of this theory to interactions of parliament and government results in the following relations: The people (as ultimate principal) delegate the power to govern to the executive (as ultimate agent) through the legislature (as agent of the people and principal of the executive). Political parties and their leaders act as mediators during this process by linking the people to both institutions (Müller, Reference Müller2000; Strøm, Reference Strøm2000; Samuels and Shugart, Reference Samuels and Shugart2014). Since delegation always comes with the risk of the abdication of power (Kiewiet and McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991), principals will aim to reduce this risk. Ex ante – meaning before the official act of delegation – principals can screen potential candidates. In the case of government formation, for instance, the governing parties will carefully screen potential ministerial candidates by checking their abilities but also their loyalty (Müller and Meyer, Reference Müller and Meyer2010). Ex post – after the agent has been appointed – the principal can keep tabs on the agent, for instance, through the use of legislative oversight to avoid that agents exploit their informational advantage to introduce policies not in the interest of the selectors (Miller, Reference Miller2005).

Legislative oversight serves the purpose of limiting information asymmetry and avoiding agency loss (Weingast and Moran, Reference Weingast and Moran1983; Kiewiet and McCubbins, Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Strøm, Reference Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003). The strategies available to representatives include: (a) extracting information about government action, (b) monitoring the execution of laws, and (c) forcing the government to defend decisions (Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2000). However, how MPs achieve these goals varies considerably depending on their institutional roles as members of the government or the opposition. Members of the opposition engage in oversight activities in plain sight through formal rights granted by the constitution and laws, while governing party members usually exercise this control through non-transparent and informal mechanisms that take place behind closed doors (for coalition meetings, see for instance Miller and Müller, Reference Miller and Müller2010). However, recent research has shown that in coalition governments, even members of the governing parties might rely on formal procedures to control their partners (Martin and Whitaker, Reference Martin and Whitaker2019; Höhmann and Sieberer, Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020; Höhmann and Krauss, 2021). Individual legislators have extensive privileges for the purpose of oversight, including oral and written questions to the government, question time, as well as legislative proposals (Mattson and Strøm, Reference Mattson, Strøm and Döring1995; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2000; Martin, Reference Martin2011). Previous scholarly work has laid out in detail how MPs hold the government accountable through these tools (Franklin and Norton, Reference Franklin and Norton1993; Wiberg, Reference Wiberg1994; Akirav, Reference Akirav2011) as well as how the institutional framework, i.e., parliament’s prerogatives, empowers or restricts opposition MPs’ capacity to oversee the executive in an efficient manner (Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2000; Friedberg, Reference Friedberg2011).

To the best of our knowledge, the influence of individual characteristics of MPs, such as their gender, but potentially also age, immigrant origin or social status, on the degree to which MPs oversee cabinet activities, has not as yet received any scholarly attention. However, feminist institutionalism (Chappel and Waylen, Reference Chappel and Waylen2013) proposes that seemingly neutral institutions and processes often impact men and women differently. We argue that women tend to conform with the institutional roles that are attributed to the behaviour of good government, and opposition members in parliament, in a more pronounced way than men. In other words, women belonging to governing parties are less likely to use oversight instruments, while women belonging to opposition parties are more likely to use oversight instruments in comparison to their men colleagues. We ground these expectations in social role theory (Eagly and Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002) as well as in women’s higher reluctance to engage in any action that might risk their re-nomination.

When engaging in legislative oversight activities, office-seeking MPs who aspire re-nomination by their party and re-election by voters (Strøm, Reference Strøm1997) will take the consequences of their actions for the future of their political career into account (Hix, Reference Hix2002). For MPs belonging to opposition parties, extensive legislative oversight activities are clearly beneficial. Questioning the working of the executive provides ground to make shortcomings of the current cabinet visible and the opportunity to set the policy agenda from outside government. Such behaviour can enhance the electoral success of the opposition party and might be rewarded by party gatekeepers with larger support for MPs’ re-nomination. However, with policy-making in committees and the plenum, media occurrences, written communication with the electorate, occurrences on public events, often also additional party office obligations, time constraints will force MPs to prioritise (Coffé, Reference Coffé2017). If this prioritisation goes at the expense of legislative oversight activities, incumbents belonging to opposition parties might raise doubts about their dedication to party goals and agenda. Still, electoral incentives, policy interests, or MPs’ self-understanding of their role as a representative might reduce the time they invest into controlling the government (see e.g., Blidook and Kerby, Reference Blidook and Kerby2011). Disengaging from legislative oversight hence constitutes a risky but viable strategy for opposition MPs.

For MPs in government, by contrast, extensive legislative oversight activities can be costly. Engaging critically in public with the work of single ministers, or the cabinet as a whole, might harm the reputation of their own party as part of the government, which decreases its electoral success. To avoid such undesired action, party gatekeepers might deny rebelling MPs from governing parties their re-nomination, thereby dissolving any incentive to engage in formal legislative oversight. However, to fulfil their institutional role as principals of the government (see e.g., Strøm, Reference Strøm2000), MPs belonging to governing parties might still aim to retrieve information from the government and hold it accountable in public.

Especially in case of coalition governments, MPs might be motivated to oversee the activities of the government members from the coalition partners. In such a case, the MPs act as principals of the coalition as a whole in order to make sure that the agent (i.e., the government members) stick to the coalition deal. Previous research has shown that coalition parties indeed make use of parliamentary questions to keep tabs on their partners (see e.g., Martin and Whitaker, Reference Martin and Whitaker2019, Höhmann and Sieberer, Reference Höhmann and Sieberer2020). In a sense, then, one could argue that it is part of the role as a coalition government MP to oversee the activities of the other government party. Still, such a strategy is risky. On the one hand, MPs might contribute to avoiding agency loss, if they prevent ministers from shirking. On the other hand, openly criticising the coalition partners could lead to conflict within the coalition and, ultimately, to an early government termination – with unknown electoral consequences for the coalition parties as well as for the individual MPs. Since parties might refuse to re-nominate MPs who display such behaviour, overseeing the government as an MP from a governing party would constitute a ‘high risk – high gain’ strategy.

We expect that women conform more thoroughly with the institutional roles for opposition or government members than men. We base this proposition on two arguments. First, if parties perceive deviation from the role of a defiant opposition or obedient government member, this is likely to be costlier for women than men MPs. This argument builds on social role theory (Eagly and Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002) which predicts that individuals hold subconscious beliefs about the traits and behaviour of the two genders that follow from stereotypes. Women are usually ascribed communal characteristics, e.g., being concerned with the welfare of others or displaying high levels of affection, helpfulness and interpersonal sensitivity. Men are, by contrast, ascribed agentic attributes, e.g., being assertive, ambitious, dominant, and independent (Bakan, Reference Bakan1966; Eagly, Reference Eagly1987). According to role congruity theory, observers perceive all behaviour that deviates from these expectations as inappropriate and punish it (Eagly and Karau, Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Heilman and Okimoto, Reference Heilman and Okimoto2007; Rudman et al., Reference Rudman, Moss-Racusin, Phelan and Nauts2012). This process was recently reaffirmed in the context of party discipline, where Clayton and Zetterberg (Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2021) showed that women display higher levels of party discipline to meet expectations about their gender’s appropriate behaviour in politics.Footnote 2 The authors argue that women tend to be associated with qualities that are more conductive to obeying rather than confronting party leadership, which incentivises them to follow the party line more strictly than men. In the context of legislative oversight, deviating from the prescribed institutional roles creates risks for the party and, therefore, constitutes a sign of a lack of communal sense for the shared faith of the party and reveals ambitions beyond party interests. In consequence, following the institutional role of an active opposition member and an inactive government member is perceived to be the appropriate behaviour for women and they should feel pressure to comply as strongly as possible.

Second, in decision-making situations, men more frequently opt for risky choices, while women prefer predictable and secure solutions. Confronted with the prospect of either foreseeable, moderate gains or uncertain, win-everything or lose-everything options, women are more likely than men to choose the former. Studies from Social Psychology provide empirical support for this relationship by revealing that men have a higher probability than women to accept financial risks both for themselves as well as for their social groups (Jianakoplos and Bernasek, Reference Jianakoplos and Bernasek1998; Ertac and Gurdal, Reference Ertac and Gurdal2012), even though the strength and substantial significance of this difference is disputed (Nelson, Reference Nelson2015). While application in Political Science is scarce, Verge et al. (Reference Verge, Guinjoan and Rodon2015) suggest that voters’ political decisions indeed follow a similar pattern: women more frequently oppose proposals for constitutional modifications that would lead to a major re-structuring of the state because they fear the risk of uncertain change to the status quo– a concern the authors observe less frequently for men. Fraile and de Miguel Moyer (Reference Fraile and de Miguel Moyer2021) show that sex differences in risk aversion also cause variation in political efficaciousness. Furthermore, studies on gender and corruption argue that women’s presence in parliaments reduces corruption at the national level due to women’s higher risk aversion, thereby suggesting that gender differences on this personality trait persist even within the selected group of MPs (Swamy et al., Reference Swamy, Knack, Lee and Azfar2001; Esarey and Chirillo, Reference Esarey and Chirillo2013). Even research engaging with women in high-profile positions in private companies presents some support for women’s higher risk aversity, even though the degree to which women and men in different types of leadership positions and sectors of the industry conform with this expectation appears to differ (Yu et al., Reference Yu, Lenard, York and Wu2017; Shropshire et al., Reference Shropshire, Peterson, Bartels, Amanatullah and Lee2021). In sum, this evidence from the citizens- and elite-level supports the claim that men are more prone to take risky decisions, while women tend to avoid having to take risks.Footnote 3

Overall, these patterns lead us to expect that women are more likely to conform with the institutional roles for opposition or government members than men. We hence expect the following:

Hypothesis 1: Women increase (decrease) their oversight activity more strongly than men when they move from government to opposition (opposition to government).

Research design

To test this proposition, we study the oversight activities of MPs in the German Bundestag between 1949 and 2013. We focus our analysis on MPs who served during multiple cabinets, to be able to see how their behaviour adapts to new governing constellations. Over the 65 years under study, Germany was led by 25 cabinets, and a total of 8,649 people served as MPs in at least two of these cabinets. The online Appendix 1 provides a list of all cabinets and their party compositions.Footnote 4

The German case constitutes an example of a typical industrial democracy. Table B1 in the online Appendix provides some evidence underpinning this claim by comparing Germany to Australia, France, Italy, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, and the UK. The table shows that, with an average of 18.5% women since 1945 and 34.8% women in the latest parliament, the share of women in the German Bundestag lies between more extreme cases such as Japan (with particularly few women MPs) and New Zealand (with particularly many women MPs). Moreover, Germany is also a typical case of an industrial democracy with regard to other important measures that are relevant for the topic analysed in this paper, such as the effective number of parliamentary parties, the proportionality of the election results as well as the polarisation in parliament. Only for the measure of proportionality, the Gallagher Index, (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher1991) does Germany have the lowest values amongst the eight countries. However, it cannot be considered an outlier since the numbers are still comparatively close to Italy and Norway. Hence, our results derived from the analysis of the German Bundestag are therefore likely to travel to other industrial democracies.

Operationalisation of the dependent variables

Our hypothesis postulates an interaction between gender and government status regarding the use of oversight mechanisms. Accordingly, our dependent variables are the changes in usage of three different oversight instruments: questions, minor requests, and proposals. We retrieve information on the frequency with which MPs make use of these instruments from the ‘Every Single Word’ data base by Remschel and Kroeber (Reference Remschel and Kroeber2022).

Parliamentary questions are the most used oversight mechanism. This is mainly due to the fact that MPs are comparatively free to ask these questions, even without the support of their party. Footnote 5,Footnote 6 Following previous research, we include both, oral and written questions.Footnote 7 Minor requests and proposals are usually not asked by individual representative but by a group of MPs. In contrast to parliamentary questions, they are more clearly associated with the opposition controlling the government. While minor requests are usually put forward in order to retrieve information from the government, proposals urge the government to act.Footnote 8 We exclude proposals and minor requests that MPs submit together with their entire fraction, since these cases do not allow us to make any conclusions about individual probabilities to act but would inflate the number of observations. Footnote 9,Footnote 10

For each of the three tools, we create a count variable that captures the activities by MPs under a given cabinet. Since we are mainly interested in changes when MPs switch from government to opposition and the other way around, we do not look at absolute numbers but rather include the first differences in our analysis. Hence, our unit of analysis is MP per cabinet and the value for our dependent variables is the change in the use of oversight mechanisms from time t-1 to t0. To illustrate the setup of our dataset, consider the following hypothetical MP from the Green party. She was a member of the Bundestag between 1994 and 2009 (LP [legislative period] 13 to 16). During that time, the Green party was in opposition, joined the government in 1998 in a coalition government with the SPD, remained in office until 2005, and went into the opposition when Merkel first became Chancellor. Since she only entered the Bundestag in LP13, there are no differences in behaviour to be calculated which is why this person is not included as an observation for that term. From LP14 onwards, we calculate the differences in behaviour for this person based on the absolute values and use them as our dependent variables.

Figure 1 provides an overview over changes in questions, minor requests, and proposals from t-1 to t0. The figure displays kernel density plots. The boxes indicate the interquartile range, while median values are marked by dots. For all three variables, the median value is zero and the vast majority of observations experiences little change in the number of oversight activities from one cabinet to the next. However, for about half of the cases, variation appears to be more pronounced, with particularly strong variation occurring in the number of questions. This variation in the way individual MPs change their oversight activities from one legislative period to the next is independent from overall levels of variation between MPs. As the summary statistics in Table A.2 in the Appendix clarify, differences in the overall amount of questions, minor requests and proposals submitted by MPs are substantial. For parliamentary questions, for instance, the mean level of activity is at around 16 questions per MP with a standard deviation of around 35 questions, a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 1212 questions. We see similar, albeit less pronounced, patterns for minor requests and proposals.

Figure 1. Distribution of change in questions, minor requests and proposals from t-1 to t0.

Operationalisation of the independent variables

Our first independent variable is the government and opposition status of MPs. We identified this information based on the party affiliation of MPs as provided by Sieberer et al. (Reference Sieberer, Saalfeld, Ohmura, Bergmann and Bailer2020). The variable takes the value ‘1’ for members of governing parties and ‘0’ for members of opposition parties. In our sample, we observe 819 cases in which MPs move from government to opposition, while 843 cases move in the opposite direction. The vast majority of cases, i.e. 6,987, do not undergo such changes in the parliamentary role.

The second independent variable constitutes the sex of MPs. For that purpose we again draw on data from Sieberer et al. (Reference Sieberer, Saalfeld, Ohmura, Bergmann and Bailer2020). A binary variable takes the value ‘0’ for women MPs and ‘1’ for men MPs. Of the observations in our analysis, MPs that served in the German Bundestag over the duration of at least two cabinets, 1,240 are women and 7,409 are men.

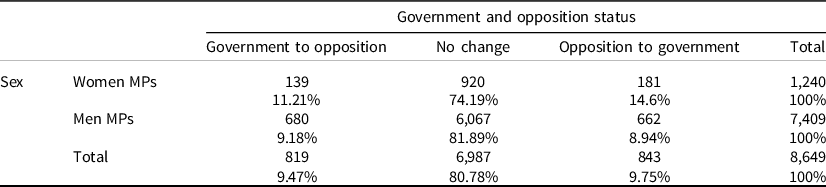

Table 1 shows how the government and opposition status of MPs interacts with their sex. While men and women are about equally likely to change from government to opposition, men are less likely than women to change from opposition to government. This pattern can be explained by the fact that the CDU/CSU and the FDP are the parties that are in government most of the time (therefore not changing from opposition to government) and the considerably low share of women in their ranks.

Table 1. Frequency of change in government and opposition status by sex of MPs in the german Bundestag between 1949 and 2013

Control variables

We also control for a number of additional variables at the MP- and contextual-level. At the MP-level, we, first of all, control for the experience of MPs in parliament to account for behavioural differences due to their tenure (Bailer and Ohmura, Reference Bailer and Ohmura2018).

Second, we include three categorical variables that capture MPs’ positional power, assuming that those who hold key positions as committee (vice-)chair, whip or parliamentary party group chair will differ from the average MP. The variables for each of the offices may take one of the following categorical values: staying in office, staying out of office, gaining office and leaving office.

Third, we take the particularities of the German electoral system into account and control for the type of mandate that an MP won. Electoral systems enabling the cultivation of personal votes (single member districts and open lists) offer more leeway for individualism in parliament with parties being less relevant for a legislator’s political advancement than an electoral system which does not allow MPs to develop a personal reputation (i.e., closed lists) (Morgenstern, Reference Morgenstern2003; Carey, Reference Carey2007; Sieberer, Reference Sieberer2010). In the German mixed-member proportional system, especially those MPs who win district mandates should, therefore, have a higher motivation to rely on oversight mechanisms in order to signal to their constituency that they are actively promoting their interests. The variable again identifies changes in the status of MPs from one legislative period to the next and has the following four categories: list to district, district to list, both times district mandate, and both times list mandate.

Fourth, we take MPs’ electoral safety into account using data by Sieberer et al. (Reference Sieberer, Saalfeld, Ohmura, Bergmann and Bailer2020), which makes use of an operationalisation suggested by Stoffel and Sieberer (Reference Stoffel and Sieberer2018). Electoral safety shapes the degree to which MPs are concerned about their electoral prospects (Kellermann, Reference Kellermann2013; Giger et al., Reference Giger, Klüver and Witko2020). The more electorally vulnerable an MP, the more likely should she be to conform with the institutional roles in the legislative oversight process, to signal that she is a good MP to voters and party gatekeepers. The continuous variable takes values between 0 and 1, with 0 indicating extremely high electoral vulnerability and 1 indicating extremely high electoral safety. To model the way change in electoral safety impacts change in oversight activities, we subtract electoral safety at t-1 from electoral safety at t0, which means that our variable ranges between −1 and 1 (for more details on the operationalisation see Appendix B).

Fifth, we also include the lagged dependent variables to make sure that our findings are not dependent on the overall frequency with which MPs use oversight mechanisms, but only their changing status as government and opposition member. We use the natural logarithm of this variable to account for the fact that changes in small numbers, e.g., from 1 to 2, are more meaningful than changes in large numbers, e.g. 100 to 101.

At the cabinet-level, we include government duration to account for the fact that MPs have more chances to use oversight mechanisms, the longer the government is in office. More specifically, we include the change in government duration between t-1 and t0.

Finally, we also include party and legislative period dummies to account for behavioural differences between parties and over time.

Sex and legislative oversight: empirical evidence from Germany

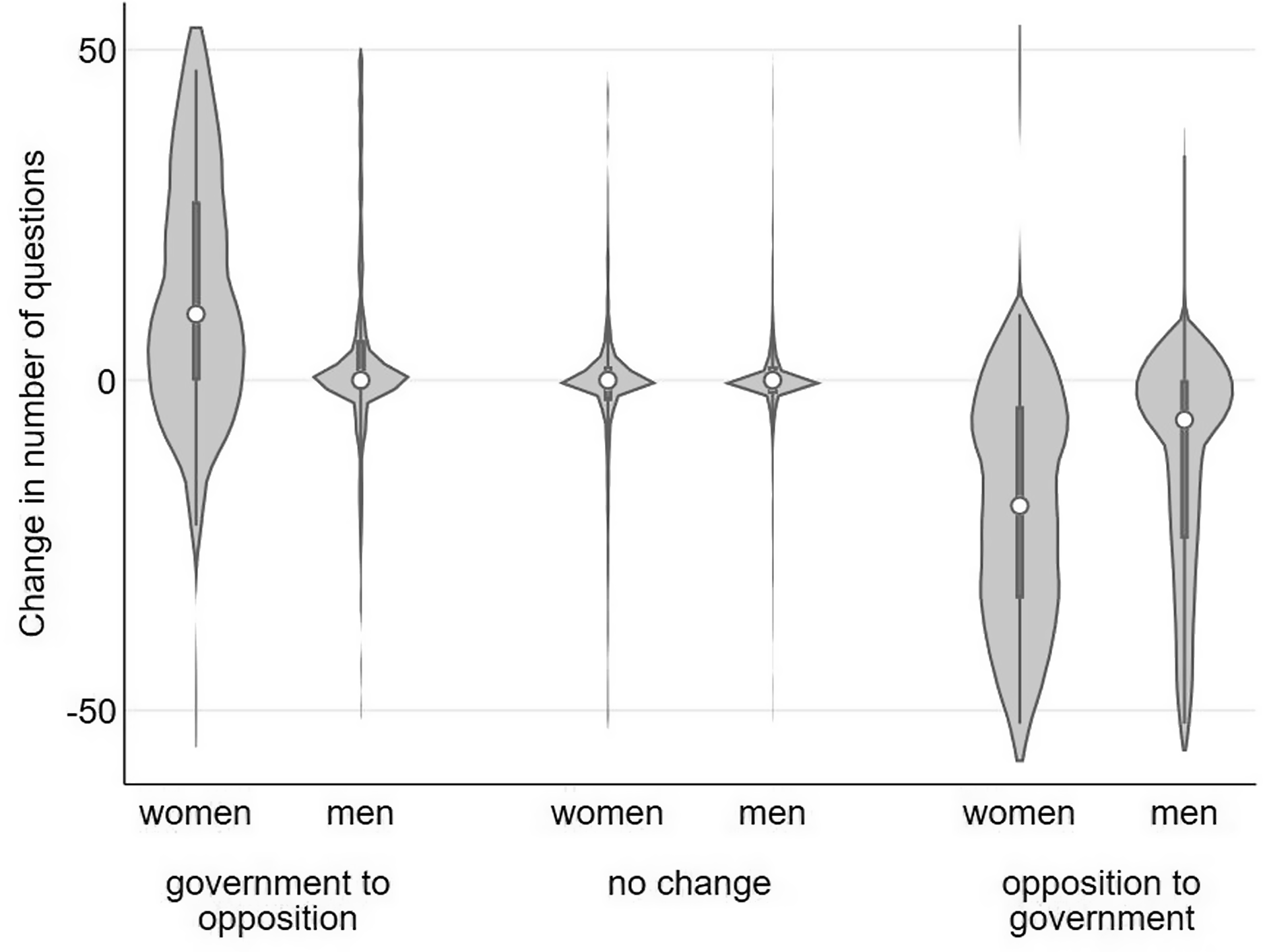

We start with a descriptive analysis of the relationship between the sex of MPs, their government or opposition status, and change in the frequency with which they engage in the three legislative oversight activities from one cabinet to the next. Figure 2 shows the distribution of change in the number of questions for six groups of MPs that follow from the combination of sex and governing status. If the governing status does not change, the vast majority of men and women barely change the number of questions they submit – even though a small number of cases show more pronounced shifts from one cabinet to the next. Within the group of MPs who move from government to opposition, the median value for women is 10, while it is zero for men. Overall, the largest part of the distribution for women indicates clear, often strong increases in the number of questions when they were just governing and are now in opposition, while most men barely adapt their behaviour in such a situation. A similar, albeit less pronounced pattern occurs for MPs who move from opposition into government. While the median value for women within this group is −19, it is −6 for men. Women hence decrease the number of questions they ask more than three times as strongly as men when moving into government. Of course, more active opposition members will have to reduce their question activities more intensively than the less active, meaning that the overall number of questions submitted by MPs previously is an important confounding factor for the multivariate analysis.

Figure 2. Distribution of change in the number of questions (t-1 to t0) by sex and change in governing status.

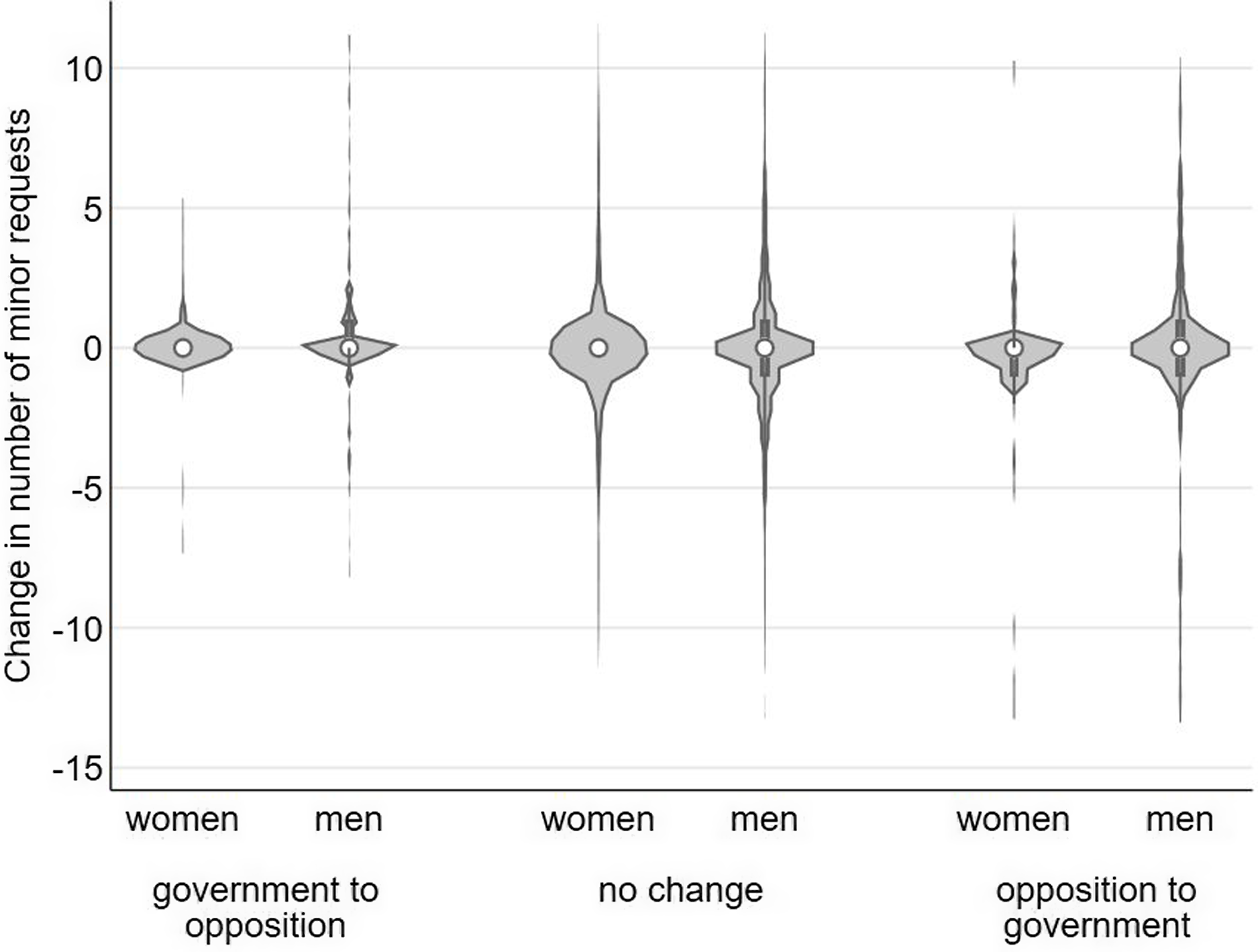

Figure 3 plots the frequency distribution of change in the number of minor requests by MPs without the support of their party. In stark contrast to the questioning activity which showed clear variation depending on the characteristics of MPs, the number of minor requests submitted by MPs barely varies for women and men who move from government to opposition, from opposition to government, or remain in their position.

Figure 3. Distribution of change in the number of minor requests submitted (t-1 to t0) by sex and change in governing status.

Figure 4 turns to the number of proposals submitted by MPs without the support of their own party and displays the same violin plots as for the other oversight activities. Similar to the questioning activity of MPs, we again observe strong differences in the frequency with which MPs support proposals depending on changes in MPs’ status as members of a governing or opposition party. The median value for women who move from government into opposition is +2 proposals, but 0 for men. Even stronger increases are frequent for women MPs, but scarce for men. The median value for women who move from opposition into government is -1, but 0 for men. While this difference is small in size, the plot clearly indicates that large numbers of women show strong decreases in their proposal activities. Notably, women who do not change their governing status also appear to decrease the number of proposals they submit, which indicates a time trend or learning effect.

Figure 4. Distribution of change in the number of proposals (t-1 to t0) by sex and change in governing status.

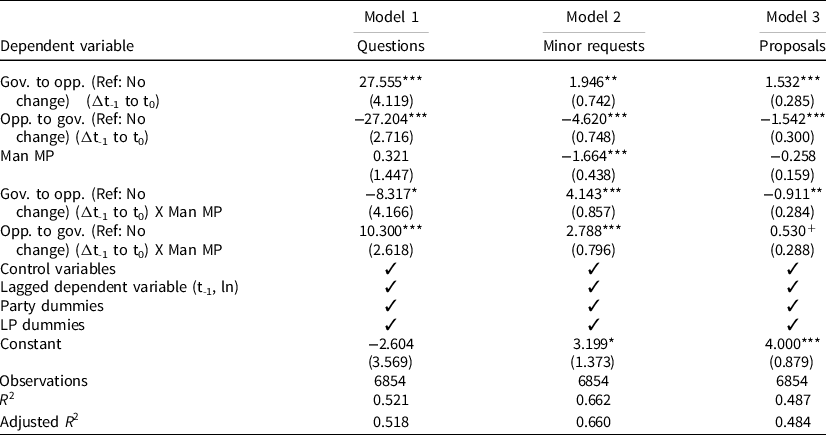

The bivariate analysis hence provides partial evidence for the expected patterns: Women tend to display larger role-conformity when it comes to questioning and proposal activities, but not for minor requests. Beyond gendered patterns of legislative oversight, this first empirical evidence hence suggests that comparing different oversight tools creates slightly different insights. To see to what extent these patterns are driven by confounding variables, we calculate an ECM for each of the three legislative activities (De Boef and Keele, Reference De Boef and Keele2008). The dependent variables are changes in the number of questions, minor requests and proposals from the previous to the current cabinet (t-1 to t0). Results of the models are presented in Table 2. Interpreting interaction effects solely based on coefficients is difficult and not very intuitive. Hence, we rely on the predicted use of oversight mechanisms as shown in Figure 5 to discuss the findings of our main analysis.

Table 2. Linear regression of change in the number of questions, minor requests and proposals submitted by MPs on their sex and change in their government and opposition status

Figure 5. Linear prediction of change in the number of questions, minor requests and proposals submitted by MPs with 95%-confidence intervals (based on Models 1 to 3 in Table 2).

A first, general finding from looking at this figure is that MPs adapt their behaviour substantially when they change their institutional roles. The overall patterns match the expected behaviour of opposition and government MPs (Mattson and Strøm, Reference Mattson, Strøm and Döring1995; Saalfeld, Reference Saalfeld2000; Martin, Reference Martin2011), with those who move from opposition into government becoming less active and those leaving government for opposition becoming more active. Second, similar to the bivariate statistics, the figure reveals differences between the three oversight mechanisms. The extent of changes in questions, minor requests and proposals decreases with the rigour of the instrument. Third, and most importantly for our hypothesis, we find sex differences in the change of MPs behaviour. In the following, we present the results in more detail and for each oversight mechanism individually.

For parliamentary questions, we find the expected sex differences in role-conforming behaviour, but they only reach conventional levels of statistical significance for MPs who move from opposition to government. Within this group, women adapt their behaviour more strongly by reducing the number of questions even more than men. Men decrease the number of questions they ask by 17.64, women by 28.26. The substantial strength of this sex difference is comparable to exiting the whip position (−11.81). For men and women who move from government into opposition, the difference in the way they change their behaviour is less pronounced, but still substantial. While the model predicts that men increase the number of questions asked by 18.50, the increase for women is at 26.50. This sex difference is nearly as sizeable as the effect of becoming parliamentary party group leader (10.16). The additional effects for men moving from government to opposition, or moving from opposition to government respectively, are statistically significantly different from zero at the 5-percent level.

Turning to requests, we again find the expected pattern for the group of MPs who move from opposition into government. While men tend to decrease the number of minor requests they submit by 3.33, the predicted change is considerably larger for women (−4.45). The strength of this effect is again comparable to or even higher than of many other variables in the model. However, for MPs who belong to parties that move from government into opposition, the model shows the opposite of the expected pattern, with men increasing their questions slightly stronger than women (4.59 compared to 2.12).

With regards to proposals, the models do not indicate any sex differences for those MPs moving from opposition to government, but they display substantial variation within the group of those who get into opposition after being in government. While men MPs increase the number of proposals they submit to the government by about 0.52 proposals when they find themselves in opposition after governing, women increase their activity in this regard by 1.68 proposals.

Overall and at large, the models hence reveal the expected stronger reaction of women MPs to changes in their institutional role. The slightly different patterns across the type of oversight mechanism could be a consequence of sex differences in the level of inter-party cooperation in policy-making. While questions and minor requests are very clearly used to criticise and oversee the work of the government, proposals have a more constructive nature and may lead to policy outputs. Women tend to apply democratic and consensual strategies and invest more time and effort into creating within- and across-party coalitions (Carey et al., Reference Carey, Niemi, Powell, Thomas and Wilcox1998; Volden et al., Reference Volden, Wiseman and Wittmer2013).Footnote 11 When asked about their leadership style, women legislators stress their dedication to compromises (Childs, Reference Childs2004). That the number of proposals submitted by women does not decrease as strongly as the number of questions or minor requests relative to men as their party starts governing could be a consequence of their higher commitment to the policy proposals of other actors.

What remains more puzzling is the question why men in opposition, who were part of the government before, submit considerably higher numbers of minor requests than women with the same experience. One potential explanation could be an interplay of two points we have mentioned before: cooperation requirements and strict oversight. Women tend to be more cooperative in their behaviour, which is especially relevant for minor requests and proposals in contrast to parliamentary questions. While minor requests are true oversight mechanisms for the opposition, proposals are more constructive. Combining these two observations, one might deduce that men could be more eager to cooperate on strict oversight but less on constructive policy work.

We ran a series of additional model specifications as robustness checks. These tests include alternative modelling strategies using a general ECM model and a Poisson model predicting the overall level of oversight activity for all MPs, not only those re-elected. We included an alternative operationalisation for the governing status as independent variable, disentangling MPs who stayed in opposition and in government. Moreover, we added the status of being a junior and senior coalition partner as a confounder. We also tested to what extent a certain sub-set of MPs drives the main effects by investigating whether the coefficients persist for MPs elected after 1994, for MPs who are electorally more safe and more vulnerable, as well as for MPs with party list and district mandates. Moreover, we introduced a three-way interaction between governing status, sex and party ideology to capture differences between men and women in left- and right-wing parties due to differences in party positions towards gender equality as well as the share of women belonging to the fraction. A last test takes substantial differences in the legislative activities of men and women into account by controlling for the degree to which MPs engage in ‘feminine’ portfolios. A detailed report and the results of all models are presented in Appendix C. We find one noteworthy deviation from our main models: Differences in the way men and women MPs adapt the number of minor requests they submit, without the official support of their PPG, when moving from opposition to government, disappear when we exclude extreme outliers (only 5th to 95th percentile). This insight suggests that gender differences for this indicator exist at the aggregate level, but are a consequence of the actions of a few men and women. Other than that, our findings remain stable across all model specifications: For questions, the hypothesised effects persist in all models and are substantial in size. For minor requests, the unanticipated positive effect for men moving from government to opposition remains stable as well. And for proposals, the expected patterns occur consistently for MPs moving from government to opposition, while the fragile estimate for sex differences of MPs moving from opposition to government in the main model remains inconsistent.

Conclusion

This article uncovers that MPs’ gender shapes their engagement in legislative oversight activities. By relying on a dataset that combines oversight activities with personal characteristics and the career paths of MPs, we show that women in the German Bundestag tend to conform more thoroughly than men to the institutional roles associated with their position as government or opposition members. When moving from government to opposition, women legislators become more active in submitting questions and proposals than men; when moving from opposition to government, they become even more restrained in their usage of questions and minor requests than men. The size of these gender gaps in reactions to changes in government status are substantial. We also find exceptions to this observation: Men who move from government to opposition become more active than their women colleagues in submitting minor requests.

From an academic perspective, such clear gendered patterns are astonishing, since legislative oversight is a highly institutionalised activity, with party dynamics almost deciding about MPs’ actions. Previous research has already highlighted how the way MPs fulfil their representative (e.g., Celis, Reference Celis2006; Höhmann, Reference Höhmann2020) and party (e.g., Coffé, Reference Coffé2017; Clayton and Zetterberg, Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2021) tasks is gendered. By adding the oversight tasks to this list, this article clarifies that all dimensions of legislative action are shaped by the sex of the actors involved. Our findings imply that the level of activity that MPs choose to display is neither determined by their party nor random, but influenced by their individual characteristics and traits. Broadening this perspective and taking other personal characteristics and personality traits of MPs into account, appears to be a promising avenue for future research. In particular, the link between MPs’ ascribed attributes and how they correlate with attitudes linked to differences in socialisation deserves more scholarly attention. We propose that women’s tendency to conform more thoroughly to the roles of a good opposition or government MP follows from social role theory as well as higher levels of risk aversity and, hence, more pronounced concerns about the consequences their behaviour might have for their re-nomination. In-depth investigations of such Social Psychological mechanisms would allow for a better understanding of the causal mechanisms underlying gender differences – but also differences in age, income or ethnicity – in legislative oversight activities. Beyond, it could also prove worthwhile to test our theoretical expectations in other contexts. While we have argued that Germany is a suitable case to test our hypotheses and that the results are likely to travel to other industrial democracies, there could be context-specific aspects such as variations in oversight mechanisms in general that could lead to important differences in terms of gender differences.

For democracy more broadly, these insights enrich our understanding of the multiple ways gender shapes the chances of politicians to participate in the political decision-making process. For instance, such a pattern could be one piece of the puzzle explaining why, despite women’s different substantial priorities in parliament (Childs, Reference Childs2001; Bird, Reference Bird2005; Celis, Reference Celis2006; Frederick, Reference Frederick2009; Höhmann, Reference Höhmann2020), their increasing numerical strength in politics sometimes fails to unfold substantial changes on the political agenda (see e.g., Atchison and Down, Reference Atchison and Down2009; Kittilson, Reference Kittilson2011; Dingler et al., Reference Dingler, Kroeber and Fortin-Rittberger2018; Reher, Reference Reher2018). The results suggest that, at least women MPs in opposition, prioritise party service over other issues they might want to pursue whereas men legislators appear to be less restrained by their concerns about how this might be perceived by party gatekeepers. Hence, they have more time and room to follow their own agenda in parliament.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773923000061.

Acknowledgements

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the 6th Conference of the ECPR Standing Group on Parliaments, the Humboldt Political Behavior Workshop and the Seminar Series at the University of Vienna. We are grateful to the participants of these events and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback as well as to Darius Ribbe for his research assistance.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.