In an oft-quoted letter dated 28 February 1778, Mozart described an aria he had composed for the tenor Anton Raaf:

I asked him to tell me candidly if [the aria] did not suit his voice, or if he did not like it, adding that I would alter it if he wished, or even compose another one … because I like an aria to fit a singer as accurately as a well-made suit of clothes.Footnote 1

While working on Idomeneo nearly three years later, Mozart again collaborated with Raaf. Yet this time, when the tenor requested some alterations to his vocal part in the Act III quartet ‘Andrò ramingo e solo’, Mozart declined to accommodate his wishes. When writing an ensemble, Mozart explained, the composer must work unencumbered, with all creative decisions ‘left to his own free will’ (‘seinen freyen Willen lassen’).Footnote 2 This statement reaffirms the ethos expressed in the earlier letter. According to Mozart, ensembles fell within the artistic remit of the composer's vision – and, by implication, solo arias did not. Rather, arias were collaborative creations, crafted by composers to favour the range, tessitura, vocal colour, technical abilities and musical predilections of the performer who would premiere them. Of course, Mozart's stated ideals do not always reflect the reality of his practices (a concern frequently faced by interpreters of Mozart's correspondence), and his desire for artistic control occasionally brought him into conflict with some singers. While writing Die Entführung aus dem Serail, for instance, Mozart complained of having to ‘sacrifice’ (‘aufopfern’) significant stretches of music to appeal to the ‘flexible throat’ of the soprano Caterina Cavalieri.Footnote 3 Yet, for the most part, he seems to have embraced the practice of composing with specific voices in mind, adjusting his music where possible to suit the intended performer.

It is widely accepted that the views described by Mozart in his 1778 and 1780 letters would have been shared by most, if not all, of his contemporaries.Footnote 4 During Mozart's lifetime, it was standard practice for composers and singers alike to treat operatic scores, and even entire roles, with a certain degree of fluidity. This applied not only during the compositional process but also in performance. Like all contemporary musicians, singers were expected to contribute extensive embellishments to the works they performed. These could include anything from local, ‘necessary’ gestures such as appoggiaturas, trills and turns, to more elaborate melodic variants that sometimes amounted to wholesale re-imaginings of a given passage. Such interventions, no less than the deliberate negotiations between Mozart and Raaf, blur the boundaries between performance and composition. An embellishing performer is, after all, a kind of composer, contributing notes, reshaping melodies, and altering the music's expressive surface. Although embellishments could be introduced virtually anywhere throughout an opera, it was in the solo aria that a singer's freedom was felt most strongly.

This much is historically uncontroversial. Yet if such facts underpin much of what is known about the cultural contexts within which Mozart worked, their implications for a critical understanding of his operas have not yet been fully realised. Particularly relevant to these issues is the practice of embellishment, which sits uneasily at the intersection of historical investigation and critical interpretation. On the one hand, it is often argued that Mozart's arias constitute the psychological centrepieces of his operas. This point, developed three decades ago by Linda Tyler and James Webster, emphasises the developmental nature of Mozart's arias.Footnote 5 According to both Tyler and Webster, it is in solo numbers that each character undergoes the musical and psychological processes that establish the dramatic scope of every opera as a whole. (This contrasts with nineteenth- and earlier twentieth-century theories of operatic drama, which, Webster notes, embodied ‘an essentially Wagnerian aesthetic’ and therefore privileged through-composed ensembles, particularly finales, as loci of interpretive significance, at the expense of discrete numbers.Footnote 6) Although it is possible to question the account of musical drama implicit in this reading, Tyler and Webster are certainly correct that, in Mozart's output, solo arias reveal the workings of each character's mind more reliably than do ensembles, where elaborate schemes, machinations, and social airs often mask individual thought.Footnote 7

On the other hand, the widespread historical practice of embellishing arias meant that it was precisely at those moments when a character was most clearly depicted that performers were freest to depart from the notes set down by the composer. Operatic characters are, in their way, real entities with complex psychological states and richly depicted inner-worlds – yet they are also musical creations, and as such their attributes are built from series of pitches, rhythms, harmonies and timbres. Considering the many letters in which Mozart complains of singers who treated his texts with undue freedom, or who demanded alterations he did not wish to make, it seems unlikely that the embellishments generally added during his lifetime reflected the same musical criteria he used when crafting his characters to begin with. This represents a rare point of tension between the aims of critical interpretation and those of historical performance, two pursuits which in most cases have mutually reinforced each other's premises, methods and ends.

If Mozart had been in a position to prescribe embellishments for his operatic arias, what types of decorations might he have added? What musical function would they have served for the characters and for the singers who performed them? In what follows, I explore these and related questions. I leave aside the issue of which specific embellishments various historical singers may have brought to the Mozart roles they performed (an area of study already well developed), and instead focus on what can be discerned of Mozart's own practices as an improviser and his preferences for the embellishment of his operas. I begin by examining three arias for which Mozart provided model embellishments: ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’ from Lucio Silla, the concert aria ‘Non sò d'onde viene’ K.294 and ‘Cara, la dolce fiamma’ from J.C. Bach's Adriano in Siria. As I argue, these decorations may tell a more detailed story than do the model embellishments Mozart composed for his keyboard works. I then broaden my enquiry to include embellishment gestures that appear throughout the other arias in Mozart's operatic repertoire. Finally, I explore the question of whether embellishment serves a musical or dramatic purpose in these operas.

Mozart's model operatic embellishments

The culture in which Mozart worked prized improvisation, and this is reflected in the notational style of his compositions. To Mozart and his contemporaries, musical notation did not represent the essence of a work; instead, it was a communicative tool whose precision could be calibrated according to the expertise of the intended reader. When Mozart composed either for himself or for professional colleagues, he often dispensed with specific instructions concerning anything from the performance of dynamics and other expressive markings to the insertion of cadenzas and embellishments. At times he even omitted textual elements which, by modern-day standards, are considered integral to the fabric of a composition (for instance, large swathes of accompanying material are left unnotated in the autographs of the Piano Concertos K.491 and K.537). Conversely, when composing for pupils or for publication, Mozart adopted a more prescriptive approach to notation. In a handful of cases, this resulted in the creation of models for types of additions usually associated with improvisation. Of these, the cadenzas Mozart composed for his mature piano concertos have received the most critical attention. However, the corpus also includes numerous fantasias, modulating preludes, Eingänge and embellishments.

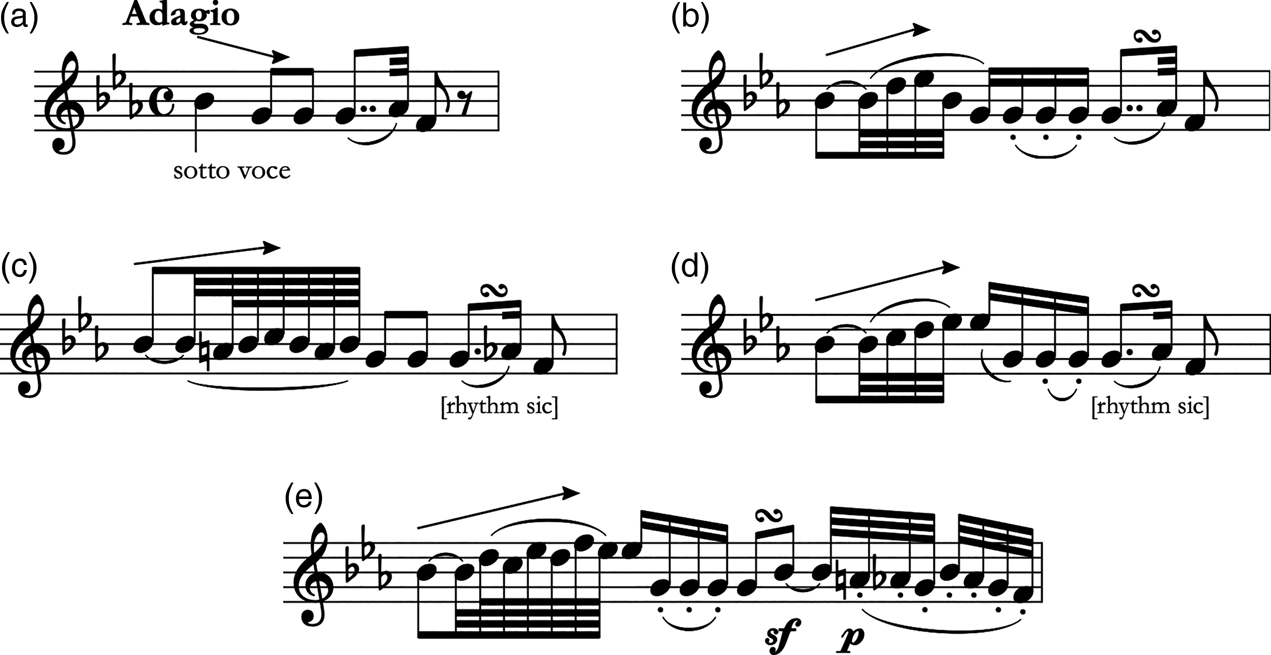

Mozart's model embellishments were produced between approximately 1773 and 1785. They include decorated versions of three contemporary arias, as well as variants for a selection of keyboard works. Musically, all these models provide a consistent picture of his preferences for embellishment. As I discuss in a recent study of Mozart's instrumental decorations, three common attributes in particular are shared by all his models, even allowing for the tailoring of individual gestures based on local context.Footnote 8 First, Mozart's embellishments are highly circuitous in their melodic shapes. Rather than simply filling intervallic gaps between pitches, Mozart meanders, often changing direction multiple times while moving from one structural note to the next. This occurs, at times, in the elaboration of individual intervals – for instance, when the descending third that begins the slow movement of K.457 is consistently embellished with figures that initially ascend before turning around to track the shape of the original (Example 1); however, it also functions on different levels of melodic detail, as when further changes of direction are introduced within these ascents (Example 1e). Second, Mozart's embellishments generally feature highly developed melodic chromaticism. This is largely self-explanatory, but its importance cannot be overstated. In some cases (including Example 1c), the chromatic alterations are minute, used to ensure proper execution of turn-like gestures. Often, however, the chromaticism is extravagant, featuring in florid departures from the original melodies. Finally, Mozart's embellishments are consistently notated as measured divisions rather than as the free tirades found in earlier eighteenth-century embellishments (including those attributed to instrumental composers such as Arcangelo Corelli). That is, Mozart's embellishments often use the same types of rhythms found more generally throughout his compositions. Taken together, these three features are significant not only for their broader aesthetic ramifications, which I discuss more fully elsewhere,Footnote 9 but also as departures from the practices espoused in contemporary treatises, many of which instruct performers to fill large melodic gaps by moving directly from one pitch to the next, without introducing further digressions or chromaticism, and often in rhythmically free styles.Footnote 10

Example 1. Melodic indirection on the gestural level. Mozart's embellishments for K.457, second movement: a) b. 1; b) b. 4; c) b. 17; d) b. 41; and e) b. 44.

Studies of Mozart's embellishments have generally focused on the decorations he provided for the keyboard works, at the exclusion of those he composed for opera arias.Footnote 11 Viewed generously, this imbalance may reflect the perception that Mozart's keyboard writing encodes aspects of his persona as a virtuoso pianist in a way that his vocal output does not. However, it may also derive from lingering notions of the primacy of instrumental music, or simply from the fact that many of the scholars who have studied the topic are themselves pianists. Given the musical consistency across all Mozart's model embellishments, a focus on the keyboard works might seem unproblematic. However, the textual histories of these sources suggest that the keyboard models may reveal less about Mozart's practices than their proponents claim.Footnote 12 Many of the keyboard embellishments decorate individual phrases, and thus shed little light on the larger-scale unfolding of variants within each piece as a whole. Even those which apply to entire slow movements reflect Mozart's aesthetics of embellishment in a single genre, and only in movements marked ‘Adagio’. Most of all, though the keyboard compositions that formed the basis for these models were composed between 1775 and 1784, the embellished variants date solely from 1784 or early 1785.Footnote 13 As a result, they offer a glimpse of Mozart's style at one phase in his development, but they say little about longer-term trends.

If Mozart's operatic embellishments have received comparatively little attention in the scholarly literature, then, there are reasons to accord them more weight than the keyboard models in understanding his preferences for melodic decoration. Unlike the keyboard models, the operatic embellishments provide a complete body of evidence pertaining to the performance of his arias. As discussed earlier, this evidence does not concern the local melodic gestures that form the basis for his embellishment vocabulary, which is consistent across all the models. Rather, the operatic models reveal higher-order features of Mozart's embellishment style. These range from the structural protocols governing the pacing of embellishment figures to more abstract notions of expression and rhetoric.

Pacing and motivic unity within individual arias

Because Mozart's operatic embellishments apply to entire arias rather than to isolated phrases, they offer insight into the pacing, structure and unfolding of embellishments over long stretches of music. At first glance, perhaps the most striking feature of Mozart's operatic embellishment models is the inclusion of decorations during the initial entrance of a vocal line. Although many treatises advise that embellishments may be withheld until the da capo (a suggestion echoed in instrumental tutors as well, which generally instruct performers to play an entire theme in its simplest written version before adding embellishments), Mozart's preferences seem to have pushed against this convention. Within the A sections of his arias, Mozart's treatment of melodic structure eschews straightforward thematic repetition, instead emphasising motivic variation. Repeated figures, however nondescript, are altered when they recur: if not through the addition of extended, florid passagework, then through more minute changes in rhythmic value or the introduction of local grace notes or trills. The ubiquity of such alterations throughout the A sections of these arias suggests that, despite the highly detailed appearance of much of Mozart's notation, he expected performers to diverge from his written texts far more often than has been acknowledged. Although the motivic variety introduced in Mozart's A-section embellishments does not obscure any ‘generative’ thematic unity that underpins the aria itself, it does suggest a style of performance that favours mutability and variance at the level of the melodic surface – an analogue to the theatrical volatility that Robert Levin has ascribed to Mozart's improvisations and indeed to his style as a whole.Footnote 14 Both the content of the A-section embellishments and the very fact of their existence suggest that Levin's descriptions are not superficial, applying to alterations that are the sole prerogative of the performer, but more deeply integrated into Mozart's aesthetic.

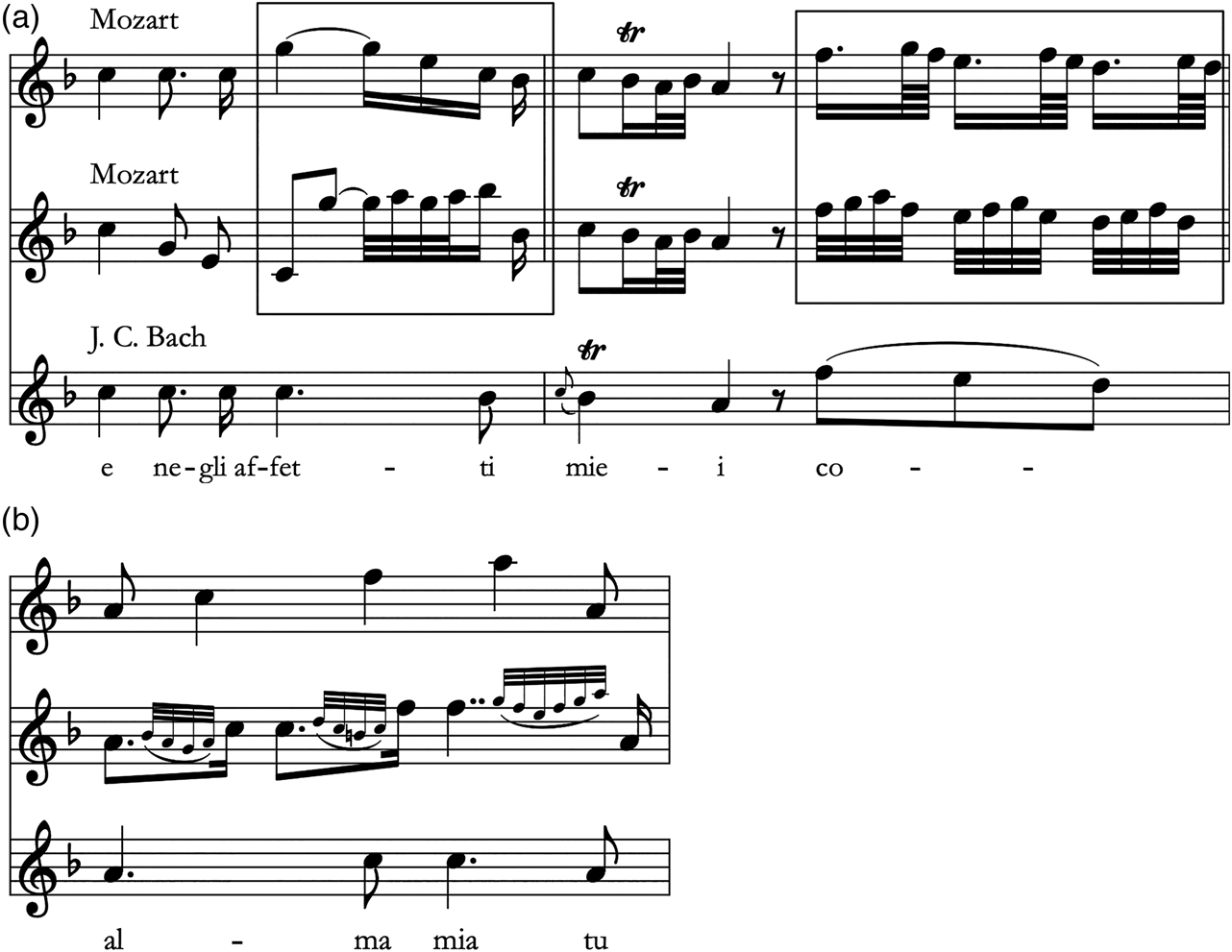

Of equal note is the relationship between Mozart's A-section embellishments and those presented during the da capo of each aria. Broadly speaking, Mozart's da capo embellishments do not introduce new stand-alone variations of an aria's theme, but rather build upon the embellishments introduced earlier.Footnote 15 One particularly transparent example occurs in his decorations for J.C. Bach's ‘Cara, la dolce fiamma’ (from Adriano in Siria). Mozart provided two sets of embellishments for this aria, and the denser model, presumably intended for the reprise, are decorations not so much of Bach's original but of Mozart's own A-section embellishments. In bar 33 of the first iteration, the embellishment ascends a fifth above the original; in the reprise, the denser embellishment does the same (Example 2a). Likewise, in bar 43 of the first iteration, the embellishment introduces an ascending arpeggio that peaks on high A, and here, too, the denser version follows suit, even imitating the arpeggiated ascent of the original variant (Example 2b). Mozart uses this structural technique in his other models as well; for instance, in the opening flourish from ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’ from Lucio Silla (Example 3). The additive nature of Mozart's embellishments imbues these arias with the same sense of development achieved in the slow movement of K.457, where the various appearances of the rondo theme seem to unfold neither as randomly applied diminutions, nor through a series of self-contained ‘variation states’, but rather with a sense of careful, large-scale planning. As before, this facet of Mozart's embellishments seems to contradict advice from contemporary treatises, where embellishments are often treated as having no structural or syntactic value, and therefore as being largely random in their deployment.Footnote 16 In Mozart's models, however, embellishments carry implications for structure.

Example 2. Mozart's embellishments for J.C. Bach, ‘Cara, la dolce fiamma’: a) bb. 33–4; and b) b. 43.

Example 3. Mozart's embellishments for Lucio Silla, ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’, bb. 8–9 and 89–90.

In addition to instances of ‘additive’ unity, in which later embellishment gestures build upon those used in previous versions of a theme, Mozart's operatic embellishment models evince a high degree of ‘static’ unity, whereby motifs introduced early in an aria appear, unchanged, in embellishments added throughout the aria. The figure that decorates the initial vocal entrance in ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’ (shown in Example 3) is reused five times in subsequent phrases throughout the aria (Example 4). Likewise, the syncopations first introduced in bar 18 are incorporated into a diverse array of subsequent gestures. Such motivic repetition is especially noteworthy given that the melodies these gestures decorate are not obviously related to each other. The reuse of embellishment figures in these cases does not imply a mechanical process in which each melodic motif is consistently elaborated in a single style; instead, the unity of the embellishment gestures seems to represent instances in which a decorative figure, once hit upon, is creatively ‘worked in’ to subsequent melodies, even at the exclusion of other potential variants. One explanation for this feature of Mozart's models is that, despite their status as premeditated, notated texts, Mozart may have been trying to imitate the act of improvisation, during which individual gestures often become fixed in the extemporiser's mind and continue to recur. In this way, Mozart could mask the compositional origins of these models, helping the performer feign spontaneity more effectively. Alternatively, the motivic unity may indicate a compositional, rather than performative, criterion on Mozart's part. He may have hoped to maintain balance between a profligacy of invention and a more carefully managed linearity that would integrate the many figures introduced each aria. This would allow him to show off his gifts as a melodist while simultaneously imbuing the embellishments with a degree of coherence and comprehensibility.

Example 4. Mozart's embellishments for ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’, bb. 30, 34, 48 and 55.

Relationship between soloist and orchestra

Apart from the six-bar insert for the Piano Concerto K.451, Mozart's model embellishments for keyboard all decorate sonata movements. In these works, the entire texture is carried by an individual pianist, who can embellish without concern for either the content of any accompanying lines or the expressive styles of any collaborating musicians. Even in the embellishments for K.451, the soloist's improvisatory freedom is essentially unfettered, since the passage's melody operates independently of the strings’ unobtrusive accompaniment. As a result, Mozart's keyboard models reveal little about the nature of embellishment in works for multiple performers. Yet it is in such works that the problems of embellishment become particularly acute. This is especially true for concertante genres, which encode a strict hierarchy between soloist and accompanist, and in which the freedom to depart from the confines of an established text represents one manifestation of such a hierarchy. Although the issue of soloistic embellishment is equally relevant to both concertos and arias, it is of special interest in the latter case, since so many of Mozart's solo vocal lines are doubled by their instrumental accompanists.

Although instrumental parts routinely double vocal lines throughout Mozart's arias, among his model operatic embellishments doubling is most pronounced in ‘Non sò d'onde viene’, K.294. In all his operatic models, and in K.294 in particular, Mozart's embellishments depart frequently from the original vocal lines – and, by extension, from their doubled instrumental parts. In some cases, these departures are modest. Mozart routinely adjusts the rhythmic values of the soloist's line during doubled melodies, such that dotted rhythms in the orchestral parts might be played against undotted rhythms in the vocal line, or vice versa (Example 5). Although these adjustments present little in the way of dissonance, the frequency with which they occur speaks to a more general point: that a degree of misalignment between simultaneously occurring melodies must have been acceptable to contemporary listeners. In other cases, Mozart's embellishments create still harsher sonorities, either through the pervasive insertion of passing dissonances, or through more sustained clashes between the soloist's line and the orchestral accompaniment. In one embellishment in K.294, the original melody (doubled by violins and bassoon) sustains a C, while the embellished variant holds a B♭ one seventh higher (Example 6). Although the doubling of melodies between soloist and orchestra is rarer in Mozart's piano concertos, it does occur – for instance, throughout the slow movements of K.488 and K.491 – and the extent of the divergences in his arias suggests that similar passages in his instrumental output are also more tolerant to embellishment than has been assumed by modern-day performers.

Example 5. Mozart's embellishments for K.294, bb. 17, 43 and 55–6.

Example 6. K.294, bb. 53–4.

It is in this context that we should understand the role of appoggiaturas throughout Mozart's operatic embellishments. Will Crutchfield has long argued that in the music of Mozart and his contemporaries, appoggiaturas must be inserted at every opportunity (on every accented prosodic syllable set to a melody with a repeated note), a conclusion based on a wide range of sources: eighteenth-century theoretical texts, instruction books, transcriptions of operatic music for instrumental ensembles, and so forth.Footnote 17 The pervasive use of appoggiaturas in Mozart's operatic models bears out Crutchfield's assertion. Throughout these embellishments, not a single repeated note is left unaltered. In many cases, Mozart's appoggiaturas create exceedingly harsh dissonances against the doubling instrumental line, particularly when the context demands the addition of chromatic alterations. However, considering the many other points of divergence between simultaneously occurring melodies in Mozart's models, such dissonances present no obstacle to the insertion of appoggiaturas.Footnote 18

The mere fact that appoggiaturas are inserted at every opportunity throughout Mozart's operatic models is, perhaps, of less interest than the various stylistic patterns associated with these insertions. Mozart's appoggiaturas do not always manifest themselves in the straightforward alteration of repeated notes on strong prosodic syllables. Although that is sometimes Mozart's strategy, he also accomplishes the same goal using more complex means, such as with elaborate trill or grace-note gestures (Example 7a). In addition, Mozart routinely alters the duration of notes comprising the appoggiatura; thus, a gesture consisting of two crotchets might be embellished as two quavers, or a quaver followed by a crotchet (Example 7b; see also Example 3). Mozart may have expected similar techniques to be used throughout his instrumental concertos, in any passage that explicitly imitates vocal genres. One example is the accompanied recitative-like section in the first movement of the Violin Concerto K.216 (bars 147–51), in which the insertion of appoggiaturas should most likely involve not only the alteration of pitches but also some rhythmic adjustment. As with the issue of doubled melodies discussed earlier, this is a straightforward case in which the practical questions facing performers of Mozart's instrumental works can be answered by considering his operatic embellishment models.

Example 7. Mozart's appoggiaturas: a) ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’, bb. 10–11; and 7b) K.294, bb. 19–22.

The topics I have addressed in this section – the divergence of a soloist's melody from doubling orchestral parts, appoggiaturas, various lines’ tolerance to embellishment – represent special instances of the more general problem of the balance of virtuosity between soloist and accompanist in a concertante work. Just as the individual manifestations of this problem carry implications for embellishment, so too do broader conceptions of virtuosity bear upon the topic.

Casually, virtuosity is often understood as an attribute of a performer, as when technical virtuosity is equated with the agility required to execute demanding passaggi. Yet virtuosity can be associated with aspects not only of performance but also of composition. The creation of complex diminutions is itself a virtuosic act in which an improviser shows off the ready flow of musical imagination, spins finely wrought decorations that transform simple tunes into complex melodies, and demonstrates an ingenuity more closely related to compositional prowess than to performance technique as such. Similarly, the melodic style of Mozart's embellishments does not simply reflect his predilection for sinewy chromaticism and circuitous melodies, but also suggests that the virtuosity implicit in his model embellishments was holistic, encompassing a wider range of skills than sheer vocal or instrumental agility. It is in this context that we might understand, for instance, the variety of appoggiatura styles used by Mozart throughout his models. He seems to flaunt an unending creativity in elaborating even the most rudimentary gesture.

Of course, the display of performative agility, too, was a consideration in the crafting of embellishments, though it does not always manifest itself through the addition of complex passagework in the soloist's line. In Mozart's operatic melodies, the balance of notational complexity is nearly always tilted away from singers and towards the instrumental parts that double them. Indeed, when vocal and instrumental parts diverge, it is generally to the instrument that Mozart accords both greater figural density and greater specificity of articulation. He often increases the technical virtuosity of the soloist's line not by adding more notes, but by leaving some difficult gestures unvaried in all of their appearances throughout an aria. It is striking, for instance, that large, multi-octave leaps are left undecorated in the operatic models (Example 8). In both his A sections and da capos, Mozart does not fill in leaps with arpeggios or scales. This may suggest that similar leaps throughout his other operas should also be performed without additional elaboration (Fiordiligi's arias come readily to mind). This contradicts Mozart's known preferences for his instrumental concertos, in which it is generally accepted that leaps must be filled as a matter of course.Footnote 19 One explanation for this divergence is that, on the piano, it is trivially easy to play such leaps at a moderately slow tempo; thus, added arpeggios not only bridge the melodic gap and provide sonic continuity but also increase the technical engagement of the performer. For a singer, by contrast, to execute large leaps itself requires considerable technical mastery, particularly when the intervals are chromatic or unusual. Thus, the insertion of arpeggios might render these passages less, rather than more, impressive. Levin has cautioned would-be embellishers that the purpose of embellishment is an ‘intensification of expression’ rather than ‘self-aggrandizing display’.Footnote 20 Yet the fact that Mozart leaves such leaps unadorned – especially taken alongside the creative complexity of the other gestures used throughout his operatic models – suggests that display in the broadest sense was indeed a priority for Mozart when composing his embellishments: one that simply manifested itself differently in operatic and instrumental music.

Example 8. ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’, bb. 22–3 and 103–4.

Chronological development of embellishment styles throughout Mozart's career

In contrast to the keyboard embellishments, Mozart's operatic models were composed over a decade. They therefore reflect the development of his style across one-third of his creative career. The embellishments for ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’ most likely date from 1773,Footnote 21 as do those for Bach's ‘Cara, la dolce fiamma’. One set of embellishments for the insertion aria K.294 was composed in 1778 along with the aria itself. Mozart then revisited the work in 1783 and provided an additional set of embellishments for the reprise. As I have already pointed out, all Mozart's model embellishments share a highly unified melodic style. What the operatic models suggest, however, is that the style of Mozart's embellishments moved in lockstep with his musical language more broadly as it developed through the various phases of his career.

Generally, the melodic style employed in Mozart's 1773 embellishments – those for ‘Ah, se a morir mi chiama’ and ‘Cara, la dolce fiamma’ – places a greater emphasis on local gestures such as trills and turns than do his later embellishments. Throughout both models, piano line-endings tracing descending thirds are decorated with trills (one instance is shown in Example 7a). Even when these early arias receive more florid, division-style embellishments, the melodic writing tends to be neatly segmented, with most gestures occurring within the confines of individual bars. The same may be said of the unembellished original melodies: both the melodies and their embellishments seem to adhere to, and even project, the structures of the phrases that underpin them. By contrast, the first set of embellishments for K.294, written some five years later, shows a move towards melodic gestures that spill over bar lines and obscure the neat phrasal divisions that continue to structure Mozart's accompaniments. In the earlier version of the K.294 embellishments, this shift manifests itself in a newfound emphasis on the decoration of upbeats, through which the style of figuration applied to a given bar is anticipated in the previous bar. In Example 6, the unembellished melody consists of two one-bar gestures, in which the second bar represents a slightly modified reiteration of the first. The embellished version, however, obscures the original motivic and rhythmic rhyme by transforming the two one-bar melodic gestures into a single utterance all bound together with flowing semiquavers. In the 1783 embellishments for K.294, this tendency towards length and sustained affective content becomes still more pronounced. In one case, a single transformative device is applied to six beats in succession: a prolonged, multi-bar gesture that would be out of place in Mozart's earlier models (Example 9).

Example 9. K.294, bb.138–9.

In addition to their melodic style, these operatic models also encode a number of changes in Mozart's use of notated expressive markings. Whereas the keyboard models contain only the occasional dynamic indication (and these solely in the slow movements of K.284 and K.457), the vocal embellishments give frequent expressive indications, including local dynamics (applied throughout entire phrases), expressive dynamics (such as sforzandi applied to individual pitches), crescendos, and even slurs that may serve as both phrasing indications and breath markings. In K.294 in particular, these markings take on a level of detail not matched in Mozart's earlier models. Here, dynamic markings do not simply indicate the relative volume of individual passages; rather, they suggest a highly affected style of performance, with individual notes receiving expressive accents (Example 10a). Although short series of dynamic markings also occasionally appear in the keyboard embellishments, these indicate a kind of written-out rubato and contribute little to the overall expressive scope of each phrase (Example 10b). By contrast, the dynamic embellishments in K.294, which occur during an extended chromatic melisma, show Mozart's vocal writing at its most charged. The passage's expressive force arises not only from the musical content but also from the deep physicality of the performed gestures, particularly the rapid changes to air-speed required in order for the soprano to bring out the dynamic emphases, and which amplify the ‘tenero affetto’ of the aria's text. As before, such passages show Mozart moving away from the more straightforward conception of virtuosity associated with embellishment, which might manifest itself in the addition of elaborate coloratura passagework, instead exploring expressive devices involving phrasing and tone colour.

Example 10. Dynamics in Mozart's embellishments: a) K.294, bb. 58 and 68–9; and b) K.457, second movement, b. 21.

This development mirrors a contemporaneous trend in Mozart's piano writing. Mozart provided two sets of cadenzas for his Piano Concerto K.271: one composed along with the work in 1776 (or shortly thereafter in early 1777), the other composed in 1783 or 1784. Each set thus dates from roughly the same period as a version of embellishments for K.294.Footnote 22 The cadenzas differ considerably in pianistic scope, demonstrating a shift of emphasis away from virtuosic figuration and towards a sensitivity to the textural possibilities afforded by the instrument. The earlier cadenzas are conservative, featuring only short runs and largely standard textures (aside from explicitly contrapuntal passages, the melody is always assigned to the right hand). The later set, by contrast, calls for a variety of accompaniment patterns, including a left hand with slurred quavers and silent downbeats redolent of the opening of the Piano Sonata K.333, and complex, four-voice textures. Because these cadenzas all draw from a single set of themes from a single concerto, they provide a consistent backdrop against which the development of Mozart's musical imagination is strikingly evident. Scholars have traditionally explained such trends in the light of Mozart's developing pianism, often locating the catalyst in new piano mechanisms designed by Johann Andreas Stein, a builder from whom Mozart purchased instruments in the late 1770s.Footnote 23 However, that the same move towards a greater textural and expressive sensitivity can also be found in Mozart's model operatic embellishments suggests a more general broadening of the expressive palette: one associated as much with the singers for whom he wrote as with the instruments on which he played. If the style of figuration used throughout Mozart's embellishments resembles his melodic style more broadly, it seems that the expressive and textural facets of those embellishments evolved alongside his use of such devices in music for other instruments – a reminder of the consistency Mozart cultivated in all facets of his professional craft, from his compositional language to his activities as a performer.

Operatic embellishment beyond Mozart's models

Despite these points of alignment, Mozart's model embellishments leave open a number of questions. Many are epistemological, the same questions that surround every textual source detailing matters of performance practice. How, for instance, do the texts of these embellishments relate to the performances for which they were used? One possibility is that the notated embellishments represent Mozart's explicit intentions as to the performance of the arias in question. Another possibility is that the models served a more expressly didactic function, encoding a range of options from which a singer could draw, but which were not intended to be performed verbatim. Were this the case, the models would be far more densely ornate than any individual performance Mozart expected them to help produce. Alongside these concerns, another point left unresolved by either the content or the source history of the models concerns their status alongside Mozart's later operas. In particular, considering the many changes wrought in Mozart's style and technique throughout the 1780s, it is not clear how model embellishments composed before 1784 should inform our understanding of the operas he produced between 1786 and 1791. In order to address these questions, it is necessary to look beyond the models, seeking embellishment gestures that appear in his compositions as part of the routine unfolding of melodies.

The problem raised by the prospect of studying such ‘extrageneric’ embellishments is that of formulating a definition. What constitutes an embellishment, and how should these be located amid the other melodic gestures in Mozart's works? The many points of convergence between Mozart's model embellishments and his style overall are the reasons that such a study is feasible, yet they also present its greatest practical obstacle. A narrow definition of embellishment (as implied, for instance, by the historical category of wesentliche ornaments) would exclude many of the gestures that make up Mozart's vocabulary, including most of the florid embellishments on display in his models, whereas a broad definition (such as that associated with Schenkerian theory, in which every phrase is an embellishment of basic harmonic functions) would identify embellishments wherever a simpler version of a theme could be imagined, which is to say everywhere.

The most appealing solution is to confine studies of extrageneric embellishment to instances of variation within repeated melodies. In this way, we sidestep philosophical tangles surrounding the ontology of embellishments, focusing instead on the specific, practical problem Mozart faced when composing or improvising embellishments: the introduction of changes within an already established melody.Footnote 24 Because repeated melodies are routinely varied throughout Mozart's instrumental and vocal compositions, his entire output may serve as a repository of embellishment gestures – not distributed throughout every melody, but embedded into the repeated phrases that undergo progressive variation throughout a movement.

This definition of embellishment does not apply to simultaneously occurring melodies, even when one version is more ornate than the other. As I pointed out earlier, throughout much of Mozart's operatic writing, the instrumental part doubling a vocal line is consistently more ornate than the vocal line – yet, despite the differences in complexity between two simultaneous lines, it is the aggregate that forms the identity of a given thematic utterance. It is only when a subsequent appearance of a melody introduces further changes that these constitute embellishments proper.

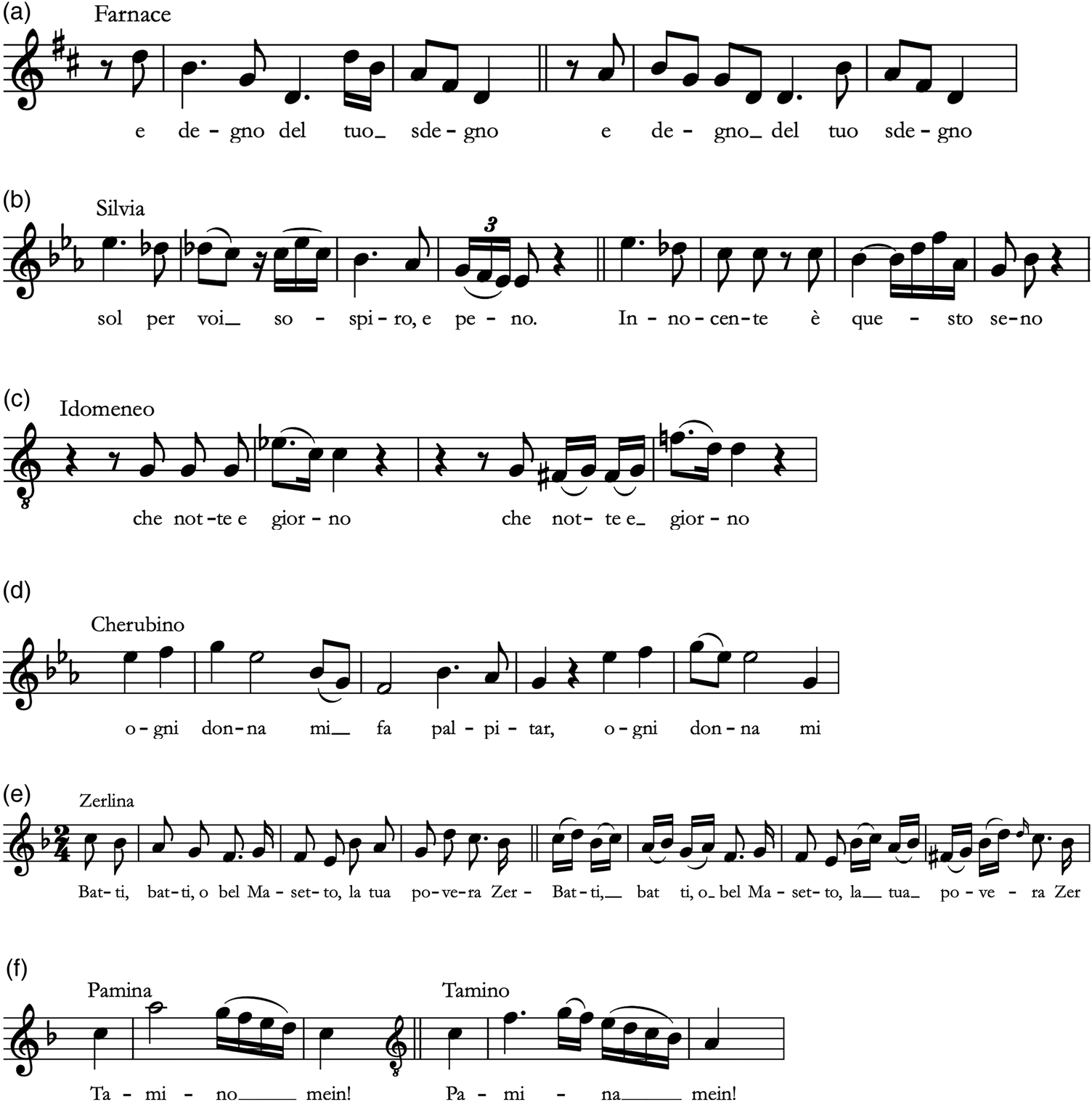

Mozart's operas contain many instances of melodic variation in repeated phrases, as shown in Example 11. In some, including in ‘Batti, batti’ from Don Giovanni (Example 11e), the placement of embellishments within the aria mirrors the structure of Mozart's instrumental rondos and slow movements. Here, decorations are applied to the return of a theme only when it occurs within a new formal section. In many other examples, however, embellishments are not separated by long stretches of music, but occur within a single phrase or period. Some closely juxtaposed embellishments are modest; in Cherubino's aria no new pitches are introduced, so the embellishment consists of little more than a rhythmic alteration (Example 11d). Elsewhere, embellishments occur in dialogic passages with more than one vocal line, as shown in the excerpt from the Act II Finale of Die Zauberflöte (Example 11f).

Example 11. Progressive elaboration in Mozart's operatic melodies, organised chronologically: a) Mitridate, no. 16, bb. 4–5 and 8–9; b) Ascanio in Alba, no. 23, bb. 66–9 and 71–4; c) Idomeneo, no. 6, bb. 15–18; d) Le nozze di Figaro, no. 6, bb. 9–13; e) Don Giovanni, no. 12, bb. 1–3 and 36–9; and f) Die Zauberflöte, Act II, Finale, bb. 278–9 and 282–3.

One of the most instructive features of these embellishments is that they tend to involve both an increase and a decrease of figural density at different points throughout a melody. In the embellishments from both Mitridate and Ascanio in Alba (Examples 11a–b), the increase of figuration is balanced by a simplification of the melodic writing elsewhere in each phrase. In Example 11a, quaver divisions embellish the descending arpeggio initially given with dotted crotchets, and this increase of density is offset by the single quaver that replaces two semiquavers. Because both gestures are sung to the same line of text, the simplification is motivated by musical concerns rather than syllabification, enunciation, or any other textual considerations. In Example 11b, the situation is slightly more complex. The structure of the embellishment does track the meaning of the text in at least one respect: The semiquaver divisions used in the initial appearance of the melody animate the word ‘sospiro’, while in the following line the removal of the semiquaver sigh mirrors the more mundane ‘è questo’. Yet Mozart immediately follows this simplification with an extravagant arpeggio – an instance of the melodic indirection so frequently shown in his model embellishments. In the case of this arpeggio, as in Example 11a, the gesture seems a result of musical rather than textual considerations: an effort to maintain the general progress from less to more figuration.

Like the model embellishments, Mozart's extrageneric embellishments also clarify issues concerning the relationship between soloist and accompanist in concertante writing. I have already pointed out that a characteristic balance between soloist and accompanist dictates certain differences between the two musical parts. Levin has applied this logic to embellishment in Mozart's piano concertos, arguing that a soloist's line should, under normal circumstances, never be less florid than the instrumental parts accompanying it.Footnote 25 In the context of Mozart's model embellishments, this consideration illuminated local cases of divergence between soloist and orchestra: appoggiaturas, the embellishment of doubled melodies and so forth. When our purview widens to include extrageneric embellishments, it becomes clear that the same applies to more elaborate interactions between soloist and orchestra. Specifically, embellishments written into the orchestral parts during instrumental interjections within an aria can indicate a minimum density for figuration in the solo line. Among Mozart's arias, the clearest illustration occurs in Fiordiligi's rondò from Act II of Così fan tutte. When the A section returns in bar 21, Fiordiligi's line is punctuated with interjections from the orchestral winds, many of which feature embellished variants of the vocal melody (Example 12). Although these variants are not prescriptive indications of the exact figures Fiordiligi should sing, they suggest a minimum density that she must employ so as not to be outdone by the orchestral accompanists. The orchestral embellishments in this aria provide useful clues as to the amount of decoration Mozart may have expected singers to add elsewhere as well. Considering the degree to which the solo horn outstrips Fiordiligi's melodies in density, the vocal line as written is vastly under-notated. It is reasonable to assume that the same is true of many other melodies in Mozart's operas – but that, because so few include instrumental obbligato of comparable scope, the notational insufficiency is rarely evident (in similarly virtuosic obbligato arias from Die Entführung aus dem Serail and La clemenza di Tito, there is less melodic overlap between instrument and singer).

Example 12. Così fan tutte, no. 25, bb. 22–3 and 23–4.

Equally relevant are the many similarities between the embellishments in Mozart's operas and those in his works of other genres. The gestures that constitute his language of operatic embellishment are virtually identical to those in both his sacred vocal music and his instrumental output, from all periods of his career. A semiquaver figure used to embellish a phrase from the sacred musical play Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots (1767) appears also in the unfinished cantata fragment K.429 (1783) and in the opera La clemenza di Tito (1791) (Example 13). The same figure appears throughout Mozart's instrumental music, including in the first and second movements of the Piano Sonata K.333 and the first movement of the Piano Concerto K.453. The same is largely true of local embellishment gestures such as trills, turns and grace notes, which receive similar treatment throughout Mozart's works of all genres, and over the course of his life. These stylistic confluences give substance to the claim that Mozart's embellishments concentrate and crystallise the melodic structures that make up his musical language as a whole. In addition, such overlaps carry practical implications for modern-day performers, who can draw embellishment gestures from Mozart's instrumental works without sacrificing stylistic integrity, at least on the level of the individual motif. Fiordiligi's rondò once again provides a useful case study, its many melodic similarities to the slow movement of K.457 suggesting various figures from the sonata that can be transferred to Fiordiligi's line with only small adjustments (Example 14).

Example 13. Mozart's embellishment figures across the genres: a) Die Schuldigkeit des ersten Gebots, no. 4, bb. 91–2; b) Cantata K.429 [fragment], second movement, bb. 25–8; and c) La clemenza di Tito, no. 16, bb. 35–8.

Example 14. Embellishing Fiordiligi's rondò with a gesture from K.457.

Performers, characters and the aesthetics of embellishment in Mozart's operas

Despite the many motivic and structural similarities between operatic and instrumental embellishments in Mozart, there is one important respect in which his treatment of embellishment differs across the two categories. This involves the frequency with which embellishments are notated within musical texts of each genre. In Mozart's instrumental compositions, hardly a movement exists that does not prescribe embellishments within repeated melodies, either in juxtaposed phrases or in subsequent formal sections. In his operas, by contrast, notated melodic embellishments are comparatively rare. They do occur, as shown in the preceding examples – yet considering the size of Mozart's operatic output, the frequency of embellishments pales in comparison with the instrumental compositions. One possibility is that the comparative lack of embellishments in these operas reflects the lack of opportunities for their insertion. The formal structures employed in the operas often dispense with straightforward thematic reprises, and even where arias include passages resembling recapitulations, the phrasal fundaments and melodic surface are often adjusted so as to preclude repeating melodies (‘Porgi amor’ is one aria in which the singer's opening material never recurs, and is perforce never embellished). Yet embellishments in Mozart's operas are often withheld not only across such large-scale formal repetitions but also in juxtaposed phrases, which generally seem to offer countless opportunities for variation.

A more compelling explanation for this disparity involves the identities of the musicians for whom Mozart composed. As I noted at the outset, singers in the eighteenth century were often granted considerable textual freedom, particularly during solo arias. It is possible that the lack of embellishments in repeated melodies from Mozart's operas reflects his willingness to allow singers the improvisational flexibility they would have come to expect. In parallel cases in his instrumental output, Mozart often adjusted his notational specificity to match the needs of the performers for whom he was writing, a fact that often bore upon the improvisatory content of the musical texts. The same line of argumentation most likely applies to the operas as well, and can account for the paucity of embellishments notated directly into the musical texts of these works.

However, other considerations complicate this picture. As we have seen, Mozart most likely subscribed to the ideal that operatic roles, and along with them, the style and specificity of their notation, should be shaped for individual singers. Yet it is not clear how often such individualised tailoring actually occurred. Whereas Mozart could draw from personal experience with his pupils when crafting concertos for them, the professional conventions dictating role-allocation in operatic performances must have presented practical obstacles. Julian Rushton has pointed out that eighteenth-century opera companies often shared roles among different singers, and has even suggested that, when composing a work such as Figaro, Mozart probably did not know who would perform each role until relatively late in the compositional process.Footnote 26 This may explain some of the ambiguity as to the musical personae of Susanna and the Countess, particularly with regard to their shared material in the Act III duet and their disguises in Act IV. It may also explain the relative scarcity of embellishments throughout repeated melodies in these works, which Mozart may have omitted neither for higher-order aesthetic reasons nor for the benefit of individual singers, but simply as a practical necessity. This would allow the performer assigned to each role – whoever that might be – to customise any figuration they would ultimately contribute. In this account, it is not Mozart's knowledge of the individual singers that dictated his notational practices, but rather his lack of knowledge. Nor is it coincidental that many of the vocal embellishments specified by Mozart occur in ensembles: musical numbers in which uncertainty as to the individual casting would be less pressing than the coordination and interaction of the musical lines (Example 15).Footnote 27 Even an aria such as ‘Batti, batti’ (shown in Example 11e), whose diminutions are among the most extensive in Mozart's operatic output, in this respect resembles a duet rather than an aria, since the solo cello is a constant, contrapuntal presence against which Zerlina's voice-leading must be aligned.

Example 15. Embellishments in Mozart's operatic ensembles: a) Le nozze di Figaro, no. 21, bb. 45–9 and 50–5; b) Don Giovanni, no. 9, bb. 6–7 and 14–15; and c) Così fan tutte, no. 29, bb. 121–4 and 126–9.

At times, Mozart was able to adjust his embellishments to suit the abilities of specific singers who were assigned to operatic roles. The compositional history of his mature operas, particularly their revivals, makes some of these priorities clear. The revisions Mozart made to his operas when adapting them for subsequent productions provide a useful glimpse into his treatment of the different musical personalities he encountered. Perhaps the most striking are the alterations he made to Figaro for a 1789 production, during which the role of Susanna (premiered by Nancy Storace) was taken up by Adriana Ferrarese del Bene. This and other cast changes prompted Mozart to insert new arias, among them ‘Al desio di chi t'adora’, which introduced a series of new vocal embellishments in large-scale formal recurrences (Example 16a) as well as in local, juxtaposed phrases (Examples 16b–c). That embellishments of this scope are not included in the original version of Figaro may speak to Mozart's confidence in the first cast. In the case of Storace, this trust was well placed. By all accounts, she was the very personification of a buffa soprano: a skilled actor and supple singer. By contrast, Ferrarese was a ‘wooden actor’, with limited flexibility and little dramatic imagination.Footnote 28 Perhaps the embellishments Mozart included in ‘Al desio’ were calculated to assist Ferrarese's feeble improvisatory skills. Considering that she also created the role of Fiordiligi, the embellishments in the horn part of the rondò can be understood in a similar light, as providing hints for Ferrarese's own decorations. Because of Ferrarese's well-documented penchant for importing virtuosic embellishments from other operas, Mozart's insertion of these ‘embellishment guidelines’ may even be seen as a gentle attempt to limit her freedom by codifying instrumental models that would be played repeatedly alongside her own decorations.

Example 16. Embellishments for the 1789 production of Le nozze di Figaro, no. 28a: a) bb. 1–2 and 33–5; b) bb. 12–13 and 14–15; and c) bb. 21–3.

Beyond these issues of musical personality and vocal ability, Mozart's operatic embellishments also reflect more general aesthetic considerations. As I have already argued, embellishment is not only a performance technique, but also an element of compositional rhetoric whose presence in a work was dictated by factors beyond the improvisatory abilities of the musicians for whom Mozart composed. When writing his operas, Mozart had to accommodate the views of patrons, theatre managers and librettists. Even more, he had to remain true to the fictional characters he was bringing to life – a skill he honed to such a degree that, as Edward Cone has put it, each operatic character becomes in Mozart's hands a kind of composer in his or her own right, whose psychological realities shape the music to which the words are set.Footnote 29 It is no surprise that in many cases, embellishment in Mozart's operas seems to serve a distinctly dramatic purpose, helping to reveal the workings of the characters’ minds.

One way in which this function manifests itself is through dramatically marked imitation among characters. The embellishments that occur during the luminous Act III duet from Figaro are, significantly, placed in a number in which Mozart and Da Ponte depict the friendship of Susanna and the Countess as transcending barriers of social class and convention. Here, imitative embellishment holds a motivic mirror to the camaraderie of these two extraordinary characters (Example 15a). In Don Giovanni, prescribed, imitative embellishment serves a slightly different purpose. A figure of two ascending chromatic semitones, Donna Anna's trademark embellishment (to be heard most clearly during her entrance in the Act I quartet), is repeatedly imitated by Ottavio; for instance, in his aria ‘Il mio tesoro’. Considering that Ottavio spends much of the opera soliciting Anna's affections, his imitation may signify sexual pursuit. The use of embellishments in Così merges these two approaches. Fiordiligi's and Ferrando's duet in Act II is a particularly rich source of embellishments, most notably in the rapturous Andante following Fiordiligi's acquiescence (Example 15c). Beginning in bar 112, the two characters sing identical embellishments for the remainder of the number, a musical manifestation of their long-delayed romantic union.

One reason for the confluence of embellishment and dramatic significance in Mozart's operas is that embellishment is one of the few compositional techniques that is both structurally significant (providing a local telos that propels the music from one phrase to the next) and a melodic device that would be available to singers. Unlike the more deeply textural technique of variation, embellishment operates solely within the melodic realm in which operatic characters give voice to their inner worlds. Whereas the techniques involved in embellishing keyboard or chamber works often draw upon textural devices that move beyond the scope of melodic elaboration, it is due to the nature of singing that melodic embellishment would remain one of the primary vehicles with which Mozart could manage both the psychological dimensions of his characters and the expressive performances of the singers who portrayed them. To the extent that his instrumental works incorporate techniques he honed as an operatic composer, and to the extent that the aesthetics of his instrumental music draws from the dramatic world of his operas, it is no accident that the crafting of embellishments became for Mozart a career-long pursuit. Whereas many contemporaries (including, notably, the other figures comprising the triumvirate of the ‘classical style’) drew upon variation as both a favourite genre and an elaborative device through which compositions could be structured,Footnote 30 Mozart continued to focus the expressive elements of his craft on the level of the melodic surface.Footnote 31 In this way, his interest in opera helped to shape the aesthetics of his compositional language as a whole.

Conclusion: problems of performance

In emphasising the musical substance of Mozart's operatic embellishments, I have left aside questions concerning modern-day performance practice. Yet the topic of embellishment presents problems for singers who perform Mozart's operas. An oft-noted paradox of historical performance is that musicians seeking to reconstruct past styles and methods must choose between two mutually incompatible aims.Footnote 32 One option is to emulate the eighteenth-century norm of soloistic individuality. Like Storace, Ferrarese, and their contemporaries, modern singers who take this approach should cultivate their own musical personae without regard for the practices of others, past or present – a method that, despite its ostensibly historicist ethos, would give rise to performances whose content diverges considerably from eighteenth-century styles. The other option, of course, is to scrupulously imitate what is known of historical practices, and, in so doing, to exchange the unreflective fluency of the native speaker for a more deliberately cultivated expressive arsenal. In both cases, the pursuit of historical fidelity produces an outcome quite different from its stated goal: the former because it repudiates the research necessary for historical revival, and the latter because such research, a sine qua non of reconstruction, breeds the inauthenticity of self-consciousness. If this point has been upheld as a general critique of the historical-performance movement, the dangers it expresses are particularly acute in the realm of opera. In opera, performers do not face this opposition within the relatively unproblematic sphere of textless music; rather, they must make their calculations based not only on musical styles but also on the fictional world of which they will become a part.

For performers hoping to adopt a Mozartian idiom when embellishing these operas, the consistency of the musical language can serve as a guide. As I have shown, Mozart's operatic and instrumental embellishments overlap considerably, if not in the frequency of their notated use, then in the musical vocabularies from which they draw. Mozart's instrumental works provide a rich store of figures from which singers can draw when embellishing his arias. As I have also shown, the exchange flows in the other direction as well, with aspects of Mozart's operatic models informing our understanding of the instrumental compositions written at various stages throughout his career.

Over the past half-century, the historical performance movement has been guided by scholarly examinations of virtually every aspect of eighteenth-century life, from detailed studies of specific musical practices to broader accounts of culture-wide trends. Yet critical focus has not always flowed in the other direction. In the case of Mozart's operas, analysis and interpretation rarely reflect findings rooted in the history of performance traditions. Even as musicologists and theorists acknowledge that Mozart expected singers to embellish his texts, such departures are rarely understood for what they are: musical alterations that should inspire a new understanding of the dramas to which these compositions give rise.