How might a composer in the early eighteenth century use music to convey the excitement of the hunt, the oppression of summer heat, the terror of a thunderstorm or the joys of the harvest? The use of any expressive medium to represent the cycle of the seasons was an audacious artistic venture. While people in seasonal climates are affected by changing conditions throughout the year, there are many aspects of the day-to-day experience of each season that are repetitive or unremarkable. To command an audience's attention, artists needed to be able to dramatize, allegorize or even defamiliarize the mundane.

This is part of the challenge undertaken in Antonio Vivaldi's cycle of concertos known as Le quattro stagioni (the title by which Vivaldi referred to them in the dedication of his Op. 8), works that were highly popular in his own day and are among the most ubiquitous examples of baroque music for many modern listeners. None the less, familiarity with these works has dulled our awareness of how little we actually know about them and the extent to which this cycle differs substantially from early modern approaches to the subject of the seasons.Footnote 1 Indeed, Vivaldi drew upon motifs from traditional seasonal depictions in literature, poetry, the visual and decorative arts and (to a lesser extent) music, but he introduced a level of visceral extremes that, as we shall see, exemplifies the emerging eighteenth-century aesthetics of nature and the sublime. The means through which he accomplished this are no less remarkable. Whereas visual artists created vivid imagery by using, for example, contrasting textiles in a tapestry or colours of paint on a canvas, Vivaldi heightened the affective experience of his four concertos through orchestration – that is, the effects created through the artful manipulation and combination of specific sonorities and textures. The orchestration of The Four Seasons, in fact, provides the key to appreciating the concertos’ originality because it allows Vivaldi to direct his listeners’ attention to specific musical events and enhances the impact of bold, expressive contrasts.

In this article I outline the special challenges that Vivaldi faced in this artistic endeavour and the ways in which his treatment of the subject of the changing seasons radically departs from tradition. At the same time, he embraced several ideals of the Arcadian reforms that became widely influential in Italian culture during the early eighteenth century. I offer new insights into Vivaldi's motivations for pairing the concertos with sonnets and then analyse the role of orchestration as a fundamental tool for accomplishing his aesthetic goals. I demonstrate how Vivaldi employs his sonic resources not only to evoke vivid aural imagery, but also to heighten the sense of physical intensity behind those images. Some of the power of these works emanates from the dramatic way in which Vivaldi juxtaposes highly contrasted textures. At the same time, he uses those specific textures and sonorities to unify expressive and pictorial motifs throughout the cycle, much as a painter might use a particular colour scheme or similar placement of figures to link multiple images. I also show how the expressive aura of each season is shaped by choices of texture and sonority. Finally, I reveal how the effects used to depict the seasons manifest an art of orchestration that had developed in early eighteenth-century instrumental music to a greater extent than scholars have recognized.

Throughout this article I use words such as ‘representation’, ‘depiction’ and ‘narrative’ with reference to both sonnets and music of The Four Seasons. Massimo Ossi argues that Vivaldi, like some of his contemporaries, believed that music had the power to represent through imitation. He points out that Vivaldi's letter of dedication prefacing the first edition of The Four Seasons claims that the captions inserted throughout the printed partbooks constitute ‘clear indications of all the things that are illustrated in [the concertos]’.Footnote 2 Thus, according to Vivaldi's own words, the concertos contain musical representations of such extramusical elements as thunderstorms, barking dogs and people falling to the ground. There is room to argue about how closely the music resembles these things, but Vivaldi's likely objective was to stimulate the imagination of his listeners through the suggestion of extramusical content rather than document the physical world in a scientific way. In using terms such as ‘illustrate’, ‘depict’ and ‘represent’, I therefore mean that Vivaldi used musical ideas to suggest an object, organism, sensation or emotion to his audience through the interplay of topoi and mimesis; these suggestions are to some degree clarified and expanded in the accompanying sonnets and captions. Likewise, although it can be argued that The Four Seasons is closer to a series of episodes than a continuous plot, I use the word ‘narrative’ because the cycle permits a listener (in both Vivaldi's day and ours) to establish a cause-and-effect chain of events.

A DIFFERENT APPROACH TO THE FOUR SEASONS AS SUBJECT MATTER

‘this is winter, but one that brings joy’ (L'Inverno/Winter)

We know surprisingly little about Vivaldi's motivation for writing a seasonal cycle and pairing sonnets with music, or about which models, if any, he drew upon for inspiration. For instance, while the concertos were first published in 1725, as part of his Il cimento dell'armonia e dell'inventione, Op. 8, Paul Everett's research suggests that the entire set of twelve works was completed and assembled c1720, with the possibility that The Four Seasons are older still.Footnote 3 Likewise, although the set, as Op. 8, was eventually dedicated to Count Václav Morzin (1676–1737), and Vivaldi's letter of dedication mentions that The Four Seasons were familiar to the count prior to their publication, we do not know if they were written for a particular patron or event.

Although Vivaldi's are the first known concertos on the subject of the four seasons, there were several visual and literary precedents for treating the concept of the seasons, individually or cyclically.Footnote 4 But relatively few musical works had done so. Among the most significant examples were Christopher Simpson's consort suites The Seasons, Jean-Baptiste Lully's Ballet des Saisons (1661), Henry Purcell's frost scene in King Arthur (1691) and his ‘Masque of the Seasons’ in The Fairy Queen (1692), Pascal Collasse's Ballet des saisons (1695), Johann Caspar Fischer's Journal du Printemps (1695) and Johann Abraham Schmierer's Zodiaci Musici (1698).Footnote 5 None of these works appears to have exerted a particularly strong influence upon Vivaldi's cycle, although they draw upon a similar body of musical figures to represent such aspects as rapid winds and shivering in the cold.

It is also significant that Vivaldi opted to use the emerging genre of the concerto, since there had been a long history of using dance suites and sonatas for descriptive music. This meant that, while the concerto's form was not as rigid as it would later become, he was working with a comparatively fixed scheme of three movements in a particular sequence (fast – slow – fast) and the somewhat regular tonal structures appropriate for ritornello form. In addition, he had to take into account the soloist's role in relation to the rest of the ensemble.

As it turns out, the concerto proved to be a surprisingly malleable genre. On the surface, the expected returns provided by ritornello form might seem too unyielding to support a narrative trajectory, but Vivaldi demonstrated just how flexible and powerful the form could be. The absence of an expected tutti ritornello could, for instance, be used to alter perceptions of time, space and narrative pacing, implying that the previous activity has been discontinued or that the scene has changed. The opposite effect – where the individually depicted events are still part of a broader, continuous scene – could be created, even emphasized, by largely unvaried appearances of a ritornello period. The availability of a solo violin part permitted multiple textural relationships with the rest of the ensemble and allowed Vivaldi to use the soloist to distinguish between the actions, thoughts or emotions of individuals (human or animal) and larger groups, in addition to juxtaposing the principal and ensemble voices to increase dramatic tension.Footnote 6 These possibilities allowed Vivaldi to highlight the challenges and rewards of using the concerto genre to suggest narrative content.

Yet by far the most fascinating uncertainty about these pieces involves the motivation behind their narrative content, as there has been surprisingly little attention paid to Vivaldi's decisions about what to represent within each season and how those choices locate his work within traditions of depicting and interpreting the seasons. Medieval and early modern cyclic representations in illuminations, paintings, sculptures, tapestries and literature tended to focus on the seasons as personified deities (popular choices including Flora or Venus for spring, Vertumnus or Ceres for summer, Bacchus for autumn and Aeolus for winter), or as a cycle of humanity's relationship with the fruits of working the land, which might also be used as an allegory of the stages of human life or as a consequence of the biblical story of the fall of Adam and Eve.Footnote 7

Vivaldi's music, sonnets (reprinted, with translations, as Table 1) and captions share certain characteristics inherited from these older traditions while introducing aspects that were decidedly modern for the early eighteenth century.Footnote 8 For instance, Vivaldi retains a fragment of the mythological apparatus, but only in an indirect manner. The brief references to Zephyrs and Boreas are almost as much a literary stand-in as an invocation of the mythical figures themselves: they were common names used to refer to the west and north winds respectively in Venetian arts and culture of the period.Footnote 9 Similarly, the name of Bacchus is referred to in Autumn only once – when the phrase ‘the liquor of Bacchus’ is used as a substitute for ‘wine’.Footnote 10

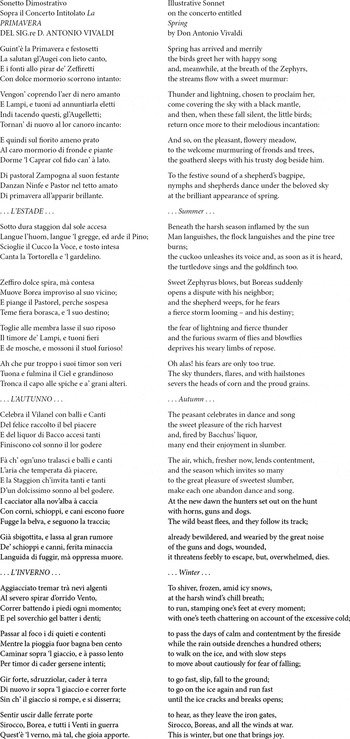

Table 1 Sonnets from The Four Seasons (cue letters omitted). Adapted from Paul Everett, Vivaldi: The Four Seasons and Other Concertos, Op. 8 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 72–75. Copyright © 1996 Cambridge University Press. Reprinted with the permission of Cambridge University Press.

Vivaldi also drew upon existing traditions of representing seasonal labours, although he greatly expanded the view of humanity's changing relationships with nature. Historically, this theme was most often represented as the sequence of planting seeds amidst the new growth of spring, harvesting crops and enjoying the sun-fed bounties of summer (often with the sun as an allegory of royal or divine assistance), frolicking in the merriment of an autumn wine season and seeking warmth by the fireside in winter (often supplemented with or replaced by recreational ice-skating).Footnote 11 Vivaldi doesn't reject this theme entirely, but places more emphasis on emotional and psychological responses to the events of each season than was typical in earlier treatments, especially fearful anticipation in summer and winter.Footnote 12

A glance at Vivaldi's treatment of summer reveals how he broke with convention to form a vision of the seasons marked by a complex relationship between humans and their surroundings. Instead of physical labour and a bountiful harvest, Vivaldi focuses attention on the physical violence of natural forces and a person's inner turmoil, turning a traditionally positive image of summer into a scene of fear and oppression; even the negative portrayal of extreme heat was an unusual contribution. Humanity's efforts to benefit from the land are thus challenged in the face of the natural world's indiscriminate destruction, although the autumn celebrations will ultimately suggest that all is not in vain. The uncontrollable quality of nature is evoked not only in the lengthy focus on explosive summer storms, but also in the great rift between the devastation of summer and the mirth that precedes and follows it.

Likewise, winter is no longer focused entirely on pleasant domestic interiors or amusements such as ice-skating; in Vivaldi's theatre it has become a setting of extreme physical conditions: bitter cold, fierce winds and violently rifting ice. Here, humanity struggles to stay warm. Nevertheless, Vivaldi also highlights moments of joy in the season, as emphasized in the final line of the sonnet (translated at the head of this section). The underlying message here, as with the cycle as a whole, is one of balance.Footnote 13

While a few of the more intense experiences, such as the extreme cold of winter, find precedents in independent treatments of a particular season or topic (such as winter landscape paintings or operatic storm scenes), the character of Vivaldi's seasons is so markedly different from the bucolic representations of earlier musical works that his cycle appears to be influenced by a different philosophical underpinning. By representing hardships brought by the extreme conditions of summer and winter, he opened the way to depicting pain and violence. In order to find the motivation for this change, we must consider other, non-musical aspects of Vivaldi's cultural milieu. For this, we do well to take a fresh look at the pairing of sonnets and concertos.

SONNETS, VERISIMILITUDE AND ARCADIAN REFORM

The most frequently discussed mystery associated with The Four Seasons concerns the origin of the sonnets that accompany the concertos, poetic expressions of the ideas and images aligned with specific passages in the partbooks through a series of letter cues, captions and reproductions of lines from the sonnets themselves. The scholarly consensus has been that Vivaldi had the basic content in mind as he composed the music and wrote the sonnets himself at some point afterwards, with the captions being added specifically for the publication of the concertos.Footnote 14 However, we might also wonder why he chose to accompany the cycle with sonnets when a simple descriptive paragraph for each would have sufficed to explain the extra-musical references. In fact, his choice of the sonnet as a poetic form provides some important clues about Vivaldi's broader aesthetic concerns.

As one of the most important forms in Italian poetry, the sonnet has intimate musical connections, not least through its name (meaning ‘little sound’ or ‘short melody’) and metrical structure.Footnote 15 Sonnets had often been used as explanatory tools for visual art, literary works, card games, geographical accounts and emblem books.Footnote 16 It is this broader convention that Vivaldi tapped into with his ‘Sonetti dimostrativi’ for each concerto, and this indicates his desire for the narrative content of the music to be understood and appreciated even by those whose comprehension of Italian exceeded their musical literacy.Footnote 17 It seems reasonable to suppose that listeners in Vivaldi's day, as in our own, often heard this music without reading or hearing the sonnets. In such cases, their ability to decipher the representations would have depended, at least in part, on their familiarity with similar musical figures in other works and an ability to link the figures together in order to apprehend their narrative significance. Vivaldi's sonnets are a tool to assist his listeners in this act of translating musical figures into a narrative framework.

Part of the reason the sonnet was a preferred medium for this type of explanation was its dialectic structure, with two major sections that could be used in several ways to make a point. For example, lines 1–8 of Spring (see Table 1) describe how the natural world forms a tranquil scene that is temporarily disrupted by a thunderstorm, while lines 9–14 detail various ways that people enjoy the pleasant aspects of spring. Vivaldi may have wanted to demonstrate similar potential in the relatively new genre of the solo concerto, where the opportunity for a dialectical relationship between solo and tutti passages offered numerous ways to contextualize melodic-rhythmic gestures and tonal architecture in a purely instrumental work.

The sonnet was also of great importance in Vivaldi's day to the literary reformers associated with the Accademia degli Arcadi and its satellite groups, being one of the poetic forms most commonly selected for public recitation and official publication by the Arcadians.Footnote 18 While no evidence has emerged of Vivaldi's membership in any such academy, their ideas were highly influential, thanks to the efforts of important writers such as Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni, Ludovico Antonio Muratori, Gian Gioseffo Orsi, Giovanni Vincenzo Gravina, Eustachio Manfredi, Scipione Maffei and Apostolo Zeno, the last two being authors of librettos that Vivaldi set to music. In addition to their promotion of the sonnet, they also argued for the importance of verisimilitude as a hallmark of good taste. As Susan Dixon notes, the Arcadians sought to simplify the relationship between allegory and narrative by focusing on structural clarity and topical references that are easily understood.Footnote 19 Compared to the complex allegorical narratives of seventeenth-century seasonal depictions, Vivaldi's cycle exemplifies this new aesthetic orientation, with limited metaphorical and allegorical references and a narrative that can be easily understood (at least on a basic level). Likewise, by using sonnets to explicate the concertos’ narrative content, Vivaldi was employing one of the Arcadians’ favoured poetic genres to enhance the narrative's accessibility while offering the concertos as an example of the new Italian aesthetic of good taste.

Vivaldi's project also mirrors Arcadian reform ideas in another important way that, as discussed earlier, sets them apart from previous seasonal depictions: an expanded focus on describing natural elements such as plants, animals and the weather. Especially in their approach to theatre, the Arcadians considered that verisimilitude could best be achieved ‘in the characters’ behaviours and in their environment or setting’.Footnote 20 The unnamed shepherds, villagers and hunters in Vivaldi's seasons are characters defined not by their mythological associations, historical fame or family lineage, but by their actions (and reactions) to their environment, which receives so much attention as to virtually become a character in an opera-withoutwords.

REPRESENTING NATURE, INVOKING THE SUBLIME

Another remarkable feature of The Four Seasons that links them to Arcadian aesthetics is their contribution to a gradual transformation and expansion, throughout the eighteenth century, of topics deemed suitable to depict the natural and pastoral worlds. Love, a topic that had previously been a centrepiece of much pastoral poetry and drama (despite the pleas of reform-minded theorists), does not obviously figure in Vivaldi's narrative.Footnote 21 In its stead, Vivaldi's cycle incorporates both pleasant and terrifying aspects of the natural world, providing a more balanced view of nature while suggesting an attempt at greater verisimilitude.

At the point when Vivaldi was writing The Four Seasons, there was already a growing tendency to acknowledge and even to celebrate the raw power of the natural world.Footnote 22 As depicted in Vivaldi's cycle, ‘nature’ is an array of forces (geological, meteorological and climatological), objects and living organisms that have the potential to oppose human interests, such as the provision of food, shelter and physical comfort. But whereas an individual or governing body could negotiate with other people who might pose a threat to security and prosperity, the risks posed by the natural world cannot be neutralized by engaging it in reasoned discourse. Given the difficulty, even impossibility, of understanding the mechanics of this natural world and overcoming its challenges to human desires, it became increasingly difficult to reduce nature to an Arcadian construct of the pastoral realm that provided a welcoming setting for people to escape the institutional controls of urban centres. Instead, rivers and fields were gradually becoming at least as likely to be seen as places of potential threat.

To judge from The Four Seasons, Vivaldi believed that indifference to human suffering and the seemingly inscrutable causes behind changing conditions of the natural world merited a less bucolic representation of nature. This same shift has been noted in depictions of the seasons by John Milton (Paradise Lost, 1667) and James Thomson (The Seasons, 1726–1730). Thomson, as Michael Cohen observes, focuses more directly on demonstrating the almost unfathomable power of natural forces that are beyond our control.Footnote 23 In this respect, Thomson's conception of nature's raw power is similar to that found in early romantic literature. Vivaldi's cycle is much closer to Thomson's treatment than Milton's, and this is undoubtedly one of the reasons why the concertos strike post-Enlightenment audiences as prescient of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century sensibilities.Footnote 24

One such sensibility is the notion of the sublime, encountered in the writings of Edmund Burke, Immanuel Kant and others, as an aesthetic experience related to terrifying, limitless power. While the majority of these writings appeared in the second half of the eighteenth century, Cohen and scholars such as Christopher Wheatley and N. A. Halmi have shown that descriptions of sublime experiences (in a Burkean sense) can be found in writings long before the term came into favour, and that even the term ‘sublime’ was not used exclusively to refer to a grand, dignified rhetorical style in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.Footnote 25 For Cohen, it was inevitable that Thomson's poems would evoke sublime experiences because he explored a wide span of the natural world, including its dark and terrifying side, rather than limiting himself to beautiful and idyllic topics.Footnote 26 True appreciation of the Arcadian idyll, as Luke Morgan notes, cannot occur without reminders of its fragility.Footnote 27 Vivaldi's similar quest for verisimilitude explains why his narrative includes intense experiences of awe-inspiring, uncontrollable power that subsequent writers associated with an emotional and psychological response to the ‘sublime’.

It is more challenging to identify properties within Vivaldi's music that might contribute to a sublime listening experience. For eighteenth-century writers, music could be sublime only when it exhibited a rhetorical style that exuded dignity and grandeur or, in the case of Burke, had characteristics so opposed to the rules of good taste that it would be of little interest to composers or audiences.Footnote 28 Yet for all their inventiveness, virtuosity and occasional surprises, Vivaldi's concertos do not possess the sheer unpredictability that Burke implies is necessary for sublime music, nor do they aspire to the noble sentiments (and religious overtones) that elicited praises of sublime grandeur for works such as the oratorios of Handel and Haydn. However, the music does enhance sublime aspects of the narrative in The Four Seasons. As it turns out, the bold textural contrasts that helped establish Vivaldi's early reputation were especially well suited to promoting his new conception of the seasons (and nature in general) because they could seize the audience's attention and hold it fast to specific details within the narrative, all the while underlining the distinct expressive character of each musical gesture.

SONORITY AND TEXTURE IN THE FOUR SEASONS

When Vivaldi began writing The Four Seasons, the solo concerto had already acquired a wide array of textural templates for fast and slow movements. However, the general framework that had been emerging over the previous decade or two called for a melodic line (or perhaps two) in the uppermost voices, inner voices that supply what I have termed ‘harmonic-rhythmic scoring’ and an active bass line that may or may not occasionally supply melodic gestures in response to prompts from the treble parts.Footnote 29 Vivaldi drew extensively upon this basic plan but, like several of his contemporaries, found myriad ways to adapt it and, in works such as The Four Seasons, to contrast it with other textural models. As we shall see, there are three factors underlying Vivaldi's handling of texture in The Four Seasons: 1) emphasizing variety by maximizing contrast between adjacent textures, 2) coordinating syntax, texture and melodic-rhythmic gestures for expressive purposes and 3) using texture to strengthen cross-references.

The most striking textural juxtapositions at Vivaldi's disposal involve use of the tutti unison, or what I have elsewhere labelled ‘full-ensemble parallel monophony’ (FEPM for short) on account of the sonic difference between true unison and parallel octaves (the latter being present in most tutti unison examples).Footnote 30 Let us begin with the intense concluding bars of the Summer concerto's first movement (Example 1). In his sonnet for this concerto, Vivaldi describes how the shepherd weeps (illustrated in the final solo section, bars 116–154) ‘because he fears he is destined for a severe storm’. This movement, a complex scene fluctuating between languid sighs, birdsongs, gentle breezes and violently contorting winds, concludes with sonic allusions to utter devastation: the downward rushing scales, scored as FEPM, seem to repeatedly crush everything into the ground (the final low g is the bottom note of the violins’ range, and the open string produces an appropriately explosive sound). However, musical depictions of storms, including those within The Four Seasons, often involve much more complex textures. Why might Vivaldi have chosen FEPM for this particular passage?

Example 1 Antonio Vivaldi, L'Estade, first movement, bars 170–174. Transcribed from Il Cimento dell'Armonia e dell'Inventione . . . Opera Ottava (Amsterdam: Le Cène[, 1725]), F-Pn, Vm7–1703, www.gallica.BnF.fr

At the time of The Four Seasons, FEPM was still a relatively novel orchestral texture.Footnote 31 Purely in terms of sonority, FEPM has three primary effects. First, it provides a single strand of music for the audience to focus on. More importantly, it takes that strand and assigns it the specific timbre resulting from multiple players in unison, as opposed to the more transparent sound of a solo player. If parallel octaves are present, the sound is further enriched by the emphasis on the octave overtones of each fundamental pitch (as if coupling a 4′ stop to an 8′ stop on an organ). Finally, FEPM distributes the single line across the entire physical space of the performing ensemble. When set alongside other textures in a performance, this effect can be very striking.

The expressive potential of FEPM has been a subject of much discussion by modern writers. Janet Levy suggests that part of its expressive agency comes from a sense of forced conformity – fear generated by the loss of self-determination.Footnote 32 John Parkinson likewise notes that the texture was frequently associated with barbarism, while John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw, who class the device under ‘Effects of Unity and Grandeur’, argue that it initially had negative or alien connotative potential but gradually lost specific extramusical associations, unless otherwise reinforced, during the course of the eighteenth century.Footnote 33 However, we need not assume that such negative connotations were a default interpretation of the texture itself, even early in the eighteenth century. An imparted sense of universal agreement could also be interpreted as communal celebration or supplication – a self-motivated desire to unite.

In fact, FEPM is used in a host of early eighteenth-century pieces that do not bear any explicit extramusical associations. Johann Joachim Quantz observed in 1752 that many concertos of a serious (as opposed to light-hearted) nature open with ritornellos interspersed with unison passages.Footnote 34 Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, writing a decade later, pointed out that the unison was very effective in focusing audience attention when the composer wanted to introduce something new or important, and this broader purpose aligns well with Vivaldi's use of the texture.Footnote 35 In The Four Seasons, Vivaldi seizes the focused intensity afforded by FEPM to convey extreme physical energy and violence.Footnote 36 All of the passages listed in Table 2 are outwardly linked to non-human agents (weather, animals and gravity), but while most are associated with negative emotional outlooks, the dogs chasing an unidentified wild animal as part of the hunt in the third movement of the Autumn concerto are framed within the positive context of sport. In each case, the monophony grabs our attention, and Vivaldi is able to harness this power for cross-referential purposes throughout the concerto cycle.

Table 2 Location of full-ensemble parallel monophony (FEPM) and related passages in The Four Seasons

We first encounter FEPM during the famous thunder scene in the opening movement of the Spring concerto (bar 44), where a rapid measured tremolo in the low register provides an abrupt contrast to the preceding homophonic ritornello depicting joyful birdsong, gentle breezes and trickling springs. This marks the beginning of an adverse turn of events, the first such downturn in the entire cycle. When violent forces appear again in summer, so does FEPM (Example 1). Summer is depicted as a source of many physical challenges, but Vivaldi deliberately saved FEPM for the very close of the first movement to indicate that the preceding battling winds are only part of a building storm. Vivaldi's aim in bars 90–109 was to convey growing tension through more complex textures and busy rhythmic activity, then provide time for the shepherd to react with growing trepidation and tears (bars 116–154). Once we become aware of the winds again (bars 155 to the end), they are no longer mere winds but ominous and violent forces in the imagination of the terrified shepherd (in a manner akin to the way Boris is haunted by hearing disturbing echoes of the bells that once announced his coronation in Acts 2 and 4 of Mussorgsky's Boris Godunov). The sonnet, in fact, tells us that the shepherd fears that a severe storm is looming, so Vivaldi has saved the most focused, intense texture of the movement for this moment of terror at the destructive power of nature.

FEPM is particularly important in the second movement of the Summer concerto, where the shepherd's uneasy rest (marked Adagio) is periodically shaken by rolls of thunder (marked Presto) scored as simulated FEPM in a low register.Footnote 37 Through similarity of sonority and texture, this thunder can be heard as referring back to the thunder in the first movement of the Spring concerto. By the end of the Summer movement, we are anxiously wondering whether the danger will pass, as it easily did in Spring, or the shepherd's fears will be realized. Vivaldi avoided ending this movement with FEPM, or anything similarly assertive, in order to hold us in suspense.

The suspense is shattered by powerful gestures opening the finale of the Summer concerto: bold downward leaps followed by repeated semiquavers. The sonnet confirms that the shepherd's worst fears have come true, as nature unleashes its fury in a violent storm of thunder and turbulent skies. The use of FEPM in these opening nine bars directly relates back to the end of the concerto's first movement, connecting the shepherd's expectations with the actual storm. Vivaldi returns to the use of FEPM three more times to reinforce the sense of sheer physical violence.

I have traced the use of FEPM in these two concertos not only to illustrate the ways in which Vivaldi used this textural device to convey intense physical violence (real or imagined), but also to show how it can generate expressive cross-references between movements while highlighting differences in the concertos’ prevailing tones. The Summer concerto is filled with evocations of physical peril, so it quite reasonably contains the most passages with FEPM. But when hearing these passages, we are reminded that spring is a much gentler season, which provokes feelings of joy rather than of misery and dread. The fact that the Spring concerto uses FEPM in only one passage helps contribute to the work's gently expressive character. Not surprisingly, FEPM is also much less prevalent in Autumn, where humanity enjoys a positive relationship with the land.

Winter, on the other hand, is a very difficult season for humanity. But because physical distress is generally caused by the effects of cold rather than by any violent motions, we encounter FEPM in just three brief passages in the finale. The first of these occurs in bars 48–50, where a scalar plunge of almost two octaves signifies slipping on the ice and falling to the ground. In addition to signifying the physical force of the fall itself, the passage serves a syntactical purpose: FEPM is used to highlight the prolonged harmonic stasis of the frozen landscape by emphasizing, even exaggerating, the movement's first full cadence (in bar 51!).

The final, brief appearance of FEPM in Winter, and indeed in the entire cycle, is cross-referential in character. The storms of summer are recollected by the representation of fierce winds in the Winter finale (bars 120–end).Footnote 38 Vivaldi further strengthens this recollection in bars 140–141 and 148–149 when he writes measured tremolos scored as FEPM starting on c1 and then stepping down to b♭, similar to the stepwise downward motion in the third movement of the Summer concerto.Footnote 39 However, the final bars of the concerto avoid FEPM, which, in the context of this cycle, might have signified total destruction. The implication is that humanity has survived the hardships of the season and will endure – a message also conveyed in the final line of the sonnet, which reminds us that winter brings both challenges and rewards. Vivaldi's interpretation of the seasonal cycle as a dynamic relationship between humanity and the natural world is therefore capped by a harmonized, conventional texture that conveys a message of resilience in the face of wild extremes.Footnote 40

Another striking texture in these concertos involves the use of bassetto scoring: passages where the normal bass-line instruments are silenced and the bass line is transferred to other instruments (typically those that normally play in an alto register or higher, such as the violin and viola).Footnote 41 For example, the bassetto is used to connect two structurally anomalous passages in The Four Seasons that share narrative subject matter as agents of relief in hostile situations. In the finale of the Winter concerto, the solo episode at bars 93–100 is interrupted when a bold downward plunge outlining V7 in C minor is followed by a dramatic shift of tempo (from Allegro to Largo) and scoring (from solo violin and basso continuo to violins and violas without basso continuo), along with a subtle harmonic twist that quickly recontextualizes the tonic resolution in C minor as the submediant of a new tonal centre, E flat major (Example 2).Footnote 42 There is no preparation for the change of tempo and new melodic material at bar 101, which comes as a complete surprise. A caption tells us that this passage represents the Sirocco wind. In contrast to the fragmented gestures, wide leaps, minor mode and quicker tempo of the preceding passages, the welcome presence of this wind is suggested by gently flowing melodic and bass lines, major mode and a slower tempo. One of the sonic characteristics contributing to the gracefulness of this interpolated episode is the use of the bassetto, as the temporary suspension of the bass register allows other voices to float over the scene, untethered to the ground.

Example 2 Vivaldi, L'Inverno, third movement, bars 98–108

This narrative is mirrored in the first movement of the Summer concerto, where the oppressive heat is temporarily made more tolerable through the welcome appearance of ‘gentle zephyrs’ (bars 78–89). Once again, the sequence of events in this passage is striking. The breeze is briefly introduced as a tease (bar 71) in the midst of a solo episode (bars 59–77), prompting the solo violin to change its discourse from calls of the turtledove to the song of the goldfinch. The reduced orchestra, without basso continuo, then presents a longer version of the breeze material before the full ensemble bursts in, forte, to signal the fierce arrival of the north wind (bar 90).

Thus while there are no motivic links between these two references to winds as a positive force, they both receive a similar textural treatment through the use of the bassetto. These two passages are, in fact, the only places in the entire cycle that feature the bassetto during what is otherwise a tutti period. The textural resemblances extend even further, as both passages are essentially built upon a two-line framework, with a harmonically enriched melody in the violins (travelling in parallel thirds) and a simpler bassetto line in the viola part – an example of what I term a ‘unison bassetto’, where any number of instruments can be assigned to play a bassetto line in unison.Footnote 43

The Sirocco passage in the Winter finale, which immediately precedes the movement's conclusion, prepares us to look beyond this concerto and apply the positive message from the sonnet's ending to the cycle as a whole. The melody beginning in bar 101 of the Sirocco episode (Example 2) is related to the melody heard in bars 25–29 of the same movement (where the image is a slow and timid walk on the ice), but the material that follows in bars 109–119 is, as both Fertonani and Everett have noted, a transformation of motives from the main ritornello of the first movement of Summer (Example 3).Footnote 44 This passage therefore encourages us to hear the concluding episode (starting in bar 120) with a distancing effect that makes it appear less menacing than it might otherwise; the sonnet, after all, invites us to ponder the joys of the seasons rather than the fears they can bring, a dissonance between poetic and musical expression that is justified through the Sirocco episode. With so much narrative importance attached to the Sirocco passage, Vivaldi was wise to use an assortment of means, including the bold textural contrast of bassetto accompaniment, to frame it in musical quotation marks.

Example 3a Vivaldi, L'Inverno, third movement, bars 109–116

Example 3b Vivaldi, L'Estade, first movement, bars 1–7

Through his use of FEPM and the bassetto, Vivaldi exploited the textural options provided by the orchestral ensemble to draw attention to important changes in motivic content and rhetorical style. In fact, Vivaldi's mastery of the wide sonic and textural palette afforded by the solo concerto reveals his innate understanding of the expressive potential of the orchestral medium. The significance of The Four Seasons results at least as much from their use of the orchestra's affective range as from the brilliance of Vivaldi's melodic, rhythmic and harmonic invention.

There is perhaps no better illustration of how Vivaldi and his contemporaries could profit from a flexible treatment of the orchestra than the long solo episode introducing the drunken villagers in the opening movement of the Autumn concerto (Example 4). What helps to make this episode so vivid is the variety of accompanying textures allied to the broad range of gestures in the principal violin part. The solo violin uses a wide range of melodic-rhythmic ideas to change rhetorical styles from languid to comically grandiloquent. Many of these alternations occur in rapid succession, conveying a sense of confusion and loss of reason appropriate to a musical representation of inebriation. Throughout, a different texture accompanies each new gesture from the solo violin, emphasizing the episode's rhetorical fantasy.

Example 4 Vivaldi, L'Autunno, first movement, bars 32–56

CULTIVATING AN EXPRESSIVE TONE

The textures and scoring combinations discussed thus far only hint at the variety of sonorities that Vivaldi called upon to tell the tale of humanity's interaction with the seasons. This study could equally well examine his use of several other scoring patterns that create a rich palette of rhythmic, harmonic and registral effects.Footnote 45 But there is a subtle yet imaginative logic behind Vivaldi's decisions about which textures to hold in reserve and which to rely upon more heavily for each season. This is why the boldest and most diverse textures are more frequently used in the two concertos illustrating the most menacing seasons, summer and winter. In addition to FEPM, elevated drama is brought to these works through the use of full-ensemble rhythmic unison, a texture that, when combined with stile concitato rhythmic activity, can provide a different kind of heightened intensity.Footnote 46 The Summer concerto is the only one to make extensive use of parallel octaves between the lowest two voices, a sonority often thought to be comparatively hollow due to the use of a single pitch class.Footnote 47

Spring and Autumn are given a much gentler treatment that is aided by a sparing use of the sharply focused textures found in the Summer and Winter concertos, and through frequent sonorities that balance richer harmonizations of individual lines with more relaxed levels of rhythmic activity. For example, Vivaldi makes extensive use of parallel melodic lines for violins (usually involving parallel thirds) to lend an air of pleasantness to melodic material in tutti passages of the concertos’ outer movements. In the first movement of the Autumn concerto, parallel melodic lines are combined with a vertically elaborated bass line (here using parallel thirds and tenths) to create a texture in which treble and bass lines are both harmonized.Footnote 48

Vivaldi's artistic responses to spring and autumn also involve several episodes with multiple rhythmic layers, as in his characterizations of summer and winter, but here he minimizes the potential for conveying an aggressive tone by assigning longer note durations to at least one of the parts. Consider the most complex texture of the entire cycle, the slow movement of the Winter concerto, where there are five rhythmic layers. To counteract the lively rhythms of the obbligato cello, Vivaldi uses the viola to create a sostenuto line of the utmost simplicity: a harmonic backdrop not unlike some of the horn and oboe writing found in orchestral music from a few decades later, sometimes referred to as the ‘wind organ’ effect.Footnote 49 The combination of principal violin and basso continuo with viola is enough to allow us to interpret the movement as a scene of repose, the pizzicato arpeggios in the violins (depicting rain falling outside) and the obbligato cello (depicting leaping flames in the hearth) reminding us of the harsh conditions we are momentarily escaping.

THE FOUR SEASONS AS A TESTAMENT TO THE POWERS OF ORCHESTRATION

As we have seen, the cycle of the seasons provided Vivaldi with numerous opportunities to showcase the power of texture and sonority to help dramatize his melodic, rhythmic and harmonic invention in support of a narrative. Yet he could also use texture and sonority effectively in works lacking overt extramusical references. For example, the opening ritornello in the finale of the Concerto for Two Violins in A minor, Op. 3 No. 8, is subjected to textural modifications that alter its impact over the course of the movement. The ritornello comprises two different cells, each orchestrated with a different texture. The first idea is a four-voice canon (bars 1–8), which is followed by two presentations of a cadential gesture scored in FEPM. The effect of this ritornello is extremely forceful: a gradual build-up from a single voice and then, just when the tension appears to have reached its peak (with the full ensemble engaged in four contrapuntal voices), there is a sudden jump to FEPM for two emphatic statements of a cadential gesture. For the next appearance of the ritornello (bars 25–36), the canonic build-up to the FEPM cadential gestures gains an air of inevitability by the addition of a downbeat pulse from the basso continuo in each bar. Following a homophonic tutti period (with solo interjections), two further tutti periods (starting at bars 82 and 114) take up the descending scales of the canonic imitation – only now there is no gradual increase of intensity, for the entire ensemble plays the canonic subject in FEPM. After one more homophonic tutti period (bars 128–131), the final tutti (from bar 142) presents both the canonic subject and the cadential gesture in FEPM. Throughout this movement, Vivaldi is able to construct an overall curve of intensity that maintains forward drive despite introducing the greatest melodic and rhythmic variety in the middle of the movement. He does this by using texture to alter the ritornello's character, removing the gradual build-up that had featured in its first two appearances, so that the later returns begin at full intensity.

Emily I. Dolan has argued that awareness and exploitation of orchestral sonorities really began during Haydn's career, as commentators began specifically to address, however briefly, the variety of sounds produced by the orchestra.Footnote 50 Yet her assertion that orchestration depends on the ability to reproduce the same effect from one orchestra to another overemphasizes orchestral variability in the earlier eighteenth century and appears to discount the idea that a string ensemble (without winds) can constitute an ‘orchestra’.Footnote 51 Dolan similarly underestimates the extent to which composers explored orchestral timbres long before there was broader acknowledgement of the art of the orchestration, and we must also consider that listeners were capable of perceiving the expressive power of orchestration before there was a suitable system or language for its critical evaluation. There would have been little reason for Vivaldi to vary texture and sonority extensively if such contrasts were not recognized and even appreciated by his performers and audiences.

While the history of most individual textures and sonorities in The Four Seasons has yet to be fully traced, precedents exist for nearly all of them within Vivaldi's previous works and in works by his contemporaries and immediate predecessors.Footnote 52 Vivaldi was therefore helping extend into the realm of the solo concerto an art of orchestration that was already being developed in multiple genres.Footnote 53 What is special in The Four Seasons, then, is the savvy way Vivaldi seized upon orchestration as a resource to ensure that the concertos are more than a parade of simple tableaux. For all the inventiveness of the principal violin part, much of the drama, excitement and memorability of these works can be attributed to the function of the entire ensemble. Long before commentators began to identify and discuss the concept of orchestration, these early eighteenth-century products demonstrated the orchestra's ability to capture the listener's imagination in ways that powerfully translate experiences of the changing seasons into a sonic experience of profound artistic value.

In blending ideas publicly discussed by Arcadian reformers with his own fondness for descriptive representation, as seen in numerous works, Vivaldi expanded his vision of the seasons to encompass both hardships and joys, presenting them as less of an idealized allegory than a cycle of physical encounters between humankind and the natural world. Taking into account the sonnets and the concertos, we can now see how both serve as part of an artistic enterprise demonstrating affinities with important new trends in early eighteenth-century aesthetics. The question of which came first – the sonnets or the concertos – is no longer so crucial, because we have a new recognition of the sonnets’ seminal role in translating musical images for a wider audience in accordance with an aesthetic that stressed intelligibility. Vivaldi's often innovative use of orchestration to clarify structure and narrative in these concertos may in fact have been motivated by Arcadian notions of verisimilitude and intelligibility. If so, this opens up entirely new ways of thinking about eighteenth-century instrumental music. In any case, Vivaldi's handling of texture and sonority in The Four Seasons reveals the richness of invention and depth of meaning that can still be uncovered in one of the most celebrated works from the baroque era.