Blame games consist of interactions between at least two sets of actors: “blame makers (those who do the blaming) and blame takers (those who are on the receiving end)” (Hood, Reference 239Hood2011, p. 7). Whether an actor is a blame maker or a blame taker during a political blame game largely depends on that actor’s political position. In the following, I call these sets of actors opponents and incumbents.

Opponents are the actors that are brought to the scene by a controversy and oppose the way that the controversy is handled by those in power. Opponents in a blame game often match the parliamentary opposition, but they can also include organized interests that are affected by the controversy and thus have a stake in the ensuing blame game. Organized interests are often the first to call attention to an issue, frame it as problematic, and publicly assign responsibility for it. Nevertheless, they ultimately depend on politicians to feed their interests into the political process. I assume that politicians in the opposition play a disproportionately large role because they represent the natural counterpart of political incumbents. Politicians in the opposition can offer a political alternative during a blame game (either a change in personnel or a different approach to addressing the controversy), and they can use their institutional prerogatives (like speaking time in parliament or contacts in the media) to take up a controversy and politicize it.

Incumbents are actors who, by virtue of their office, are called on by opponents to address a controversy and eventually face consequences for actions or omissions that allegedly led to the controversy or for their handling of the controversy as such. Incumbents encompass individual ministers or secretaries, as well as the ruling government as a whole. In addition to the parties that make up the government, incumbents, like opponents, may receive support from organized interests for which the controversy comes at an awkward moment and who may like things to stay as they are.

2.1 More Than Routine Political Business: Blame Games as Distinct Political Events

The occasion of a political blame game is a controversial event that attracts the attention of citizens, media, and politics. Controversial political events can take a wide variety of shapes. The first category of controversial events that usually comes to mind are cases of private misconduct – typical examples include presidents who have extramarital affairs or parliamentarians who misappropriate public funds (Hood, Reference 239Hood2011; Sabato, Reference Sabato2000). A government’s inability to confront exogenous threats, such as terrorist attacks or natural disasters, may also constitute controversial political events (Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell and ‘t Hart2008; Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2012). Government decisions that deliberately impose losses on constituents, like pension cuts or closures of military bases, can likewise be controversial (Pal & Weaver, Reference Pal and Weaver2003). Finally, there are the many endogenous malfunctions of a political system, such as policy failures or government blunders, that undoubtedly fall under the rubric of controversial events (Hood et al., Reference Hood, Jennings, Dixon, Hogwood and Beeston2009; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Lodge and Ryan2018; King & Crewe, Reference King and Crewe2014; Lodge et al., Reference Lodge, Wegrich and McElroy2010; McConnell, Reference McConnell2010a). The chaotic launch of the healthcare.gov website and the Swiss lobbing affair fall into this category.

While controversial events are at the basis of political blame games, they do not (yet) constitute clearly established political scandals or failures. A scandal or failure already implies a certain level of politicization (during a blame game). A policy controversy only turns into a political scandal if the opponents in a blame game successfully politicize the controversy and force incumbents into heated blame game interactions. Hence, the course of a blame game decides whether a controversy develops into a venerable political scandal or stays a low radar issue. The study of blame games therefore also contributes to our understanding of political scandalization processes (Adut, Reference Adut2008; Allern & von Sikorski, Reference Allern and von Sikorski2018, p. 3017; Entman, Reference Entman2012).

In this book, I focus on blame games triggered by policy controversies because they are at the heart of political struggle in modern democratic political systems. In doing so, I side with political science research that has begun to abandon an overly narrow conception of politics that primarily revolves around vote choice, elections, and campaigns. Following in the footsteps of E. E. Schattschneider (Reference Schattschneider1935), Theodore Lowi (Reference Lowi1964), Hugh Heclo (Reference Heclo1974), and others who argue that policies create their own politics, scholars have developed a policy-focused political analysis (Hacker & Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2014; Mettler & SoRelle, Reference Mettler, SoRelle, Sabatier and Weible2014; Pierson, Reference Pierson1993). This research perceives political contestation more broadly, appreciating that politics is not only about winning votes but also about gaining control over particular policies. Policy controversies are commonplace in modern democratic political systems where policy infrastructure thickens as governments set about regulating an increasing number of challenges and situations (Bovens & ‘t Hart, Reference Bovens and ‘t Hart2016; Orren & Skowronek, Reference Orren and Skowronek2017). The blame games that develop in their wake are opportunities for actors to change policy trajectories. This is why it is important to know what political actors say and do during policy controversy-induced blame games and what consequences their interactions produce.

Policy controversies stand out from and interrupt routine political processes, attracting more attention than daily political business, such as the occasional debate about pension reform or the quarrel about next year’s budget. While most of the issues that linger on the political agenda of a democratic political system must be addressed someday and somehow, the political management of controversies is special. Democratic political systems must process them without delay and under heightened attention from various parties. Incumbents are usually surprised by policy controversies, and they would have preferred to avoid them. As politically responsible actors, they have a lot to lose and not much to win. This constellation is different from the blame games that develop when incumbents deliberately impose losses on constituents, like the aforementioned pension cuts or military base closings. The politics of pain that usually surround these political decisions (Pal & Weaver, Reference Pal and Weaver2003; Vis, Reference Vis2016) represent an altogether different challenge to political incumbents. While likewise dangerous and risky, incumbents can usually prepare for the politics of pain, that is, they can strategically time a loss-imposing decision or try to present it in a less blame-attracting way.

The processing of policy controversies usually occurs in several, mutually nonexclusive steps. The policy controversy must first be properly understood: What happened and why did it happen? For instance, why did the Obama administration launch the healthcare.gov website in such a chaotic way? Was there an IT breakdown that could have been avoided? Then the controversy must be evaluated: what exactly is bad about it and how bad is it? For example, is it really bad if the Kazakhstanis interfere in Swiss domestic affairs, or is it just the way things are nowadays? And finally, consequences, in the form of drawing conclusions, learning, punishment, or course corrections, must be agreed upon and brought about. For instance, should a parliamentarian submitting a motion for a foreign regime have to resign, or is an apology enough? Should the Swiss parliament revise lobbying regulations? Needless to say, the management of policy controversies is almost always a much contested exercise. Policy controversies are not mere factual events, but rather they entail a political assessment of whether and how a policy has failed, and whether this failure should be considered a scandal (Bovens & ‘t Hart, Reference Bovens and ‘t Hart2016; McConnell, Reference McConnell2010b). In short, when it comes to the political management of policy controversies, political actors most often disagree about what happened and why, whether it is good or bad, and about which consequences need to be drawn.

The Motives and Strategies of Opponents

For those seeking power, policy controversies present an opportunity to damage incumbents and effectuate change. Quite simply, policy controversies provide blaming opportunities for opponents. Blaming the politician in charge, or the whole government, for a controversy is potentially reputation damaging: ministers or secretaries may be weakened in office, be forced to resign, or the government may suffer a drop in its approval ratings. Moreover, opponents may attempt to use the controversy to change policy. Blame pressure from opponents may prompt incumbents to adapt an existing policy or to address an (inconvenient) policy problem. Since conflicts over policy often stretch over considerable time spans, a particular blame game may only represent a phase of intensified conflict in a long-term policy struggle. Therefore, it is likely that opponents may strive to institutionalize their political gains for subsequent rounds of the policy struggle – even if imminent policy change is hard to bring about. In short, bringing about a change in the current distribution of reputation and/or changing policy are the substantive goals of opponents during a blame game.

Christopher Hood defines blaming as “the act of attributing something considered to be bad or wrong to some person or entity” (Hood, Reference 239Hood2011, pp. 6–7). In order to blame those in office, political opponents thus work on emphasizing both the perceived loss and perceived responsibility of a controversy (Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2017; Sulitzeanu-Kenan & Hood, Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan and Hood2005). Highlighting the perceived loss dimension means convincing the public and media that a controversial event actually constitutes a loss in some way: a loss of money, a loss of time, or even a loss of life. For some controversies, the loss is clearly discernible for everyone. For others, what actually constitutes a loss is less clear. Highlighting the perceived responsibility dimension means that opponents seek to make incumbents responsible for the loss. What happened was not just the consequence of some magical amalgamation of circumstances, but it supposedly directly flowed from the actions or inactions of the government. In the empirical analysis that follows, I will therefore look at whether and how opponents point to and exaggerate the negative aspects of a policy controversy or frame it in moralistic terms (the perceived loss dimension), and ascribe the controversial event to the conduct of incumbents (the perceived responsibility dimension) (Brändström & Kuipers, Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003; Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2018; Mortensen, Reference Mortensen2012).

The Motives and Strategies of Incumbents

For incumbents, blame from opponents is dangerous. It threatens their reputation and may force them to yield to policy demands. Therefore, the incumbents’ primary motive during a blame game is to stay out of it for as much and as long as possible. However, if they cannot ignore blame pressure, they must begin to address the controversy by adopting various blame-management strategies (Hood, Reference 239Hood2011; Weaver, Reference Weaver1986). Numerous categorizations of blame-management strategies exist. Of these categorizations, Hood’s (Reference 239Hood2011) distinction between agency, policy, and presentational strategies is the most widely used. Agency strategies seek to reallocate responsibilities and competencies in order to shift the risk of being blamed to others. An example of an agency strategy is the delegation of activities to actors lower down the administrative hierarchy. Policy strategies address the policy as such. This strategy type seeks to make governmental activities less blameworthy by redesigning policies or changing the ways that they emanate (Hood, Reference 239Hood2011). However, incumbents cannot usually rely on agency and policy strategies during policy controversy-induced blame games because these strategies can only be used before blame has materialized, that is, they cannot usually be put in place on an ad hoc basis, or they at least lack credibility if they are implemented swiftly (Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2017). During policy controversy-induced blame games, incumbents therefore mainly rely on presentational strategies and forms of discursive interaction (Hansson, Reference Hansson2018a). Instead of reallocating competencies or changing the substance of a policy, presentational strategies intend to shape public impressions and frame the political debate about a controversial event (Boin et al., Reference Boin, t Hart and McConnell2009b; Hood, Reference 239Hood2011; König & Wenzelburger, Reference König and Wenzelburger2014; McGraw, Reference McGraw1991). Presentational strategies essentially encompass relativizations of the controversy and attempts to deflect blame onto actors and entities somehow involved in the controversy, such as subordinate or adjacent administrative bodies (Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2018). In addition to genuine presentational strategies, incumbents can take forms of activism, such as launching an inquiry or proposing (symbolic) reforms (Brändström, Reference Brändström2015; Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan2010). Finally, incumbents often seek to signal a specific attitude during a blame game. For instance, they may want to appear as prudent crisis managers, caring mothers or fathers, or energetic problem solvers. Activism and the signaling of a specific attitude are nonverbal forms of presentational blame management (Hansson, Reference Hansson2018b). In the empirical analysis of blame games, I will categorize incumbent behavior along three dimensions: the genuine presentational strategies incumbents apply, the activism they exhibit to address a controversy, and the attitude they adopt during a blame game.

In this conceptualization of the participants in a blame game and their motives and strategies, political actors are not merely conceived as reputation-conscious, vote-seeking political actors (Busuioc & Lodge, Reference Busuioc and Lodge2016) but also as actors who struggle to reshape a policy area in enduring ways by gaining the prize of policy during a blame game (Bawn et al., Reference 235Bawn, Cohen and Karol2012; Hacker & Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2014; Weaver, Reference Weaver2018). Only this more complex picture of political actors allows us to capture what political actors are really up to when they play a blame game. Hence, as far as policy controversies are concerned, blame games cannot merely be perceived as framing contests (Boin et al., Reference Boin, t Hart and McConnell2009b; Edelman, Reference Edelman1988), they are also conflicts that revolve around substantial policy issues.

The Complexity of Blame Games

The multitude of blame-generation and blame-management strategies that political actors can adopt and their resulting interactions convey a first impression of the complexity of blame games. Blame games emerge due to a wide variety of policy controversies. They involve longer-lasting series of interactions in multiple arenas, and they are embedded in long-running, often confusing, policy struggles. To comprehensively capture blame games, that is, to understand their interactions and their consequences for the politicians involved and the policies at their core, we need to look at the political and policy contexts in which blame games are embedded (Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2015).

So far, however, context-sensitive research on blame games is scarce. Existing attempts to understand context usually focus on only one or a few contextual factors, and they examine their influence on blame games while ignoring the influence of other factors (Brändström & Kuipers, Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003; Hood et al., Reference Hood, Jennings and Copeland2016; Moynihan, Reference Moynihan2012). Moreover, the causal impact of contextual factors is usually only discussed ceteris paribus, meaning that the interrelation between contextual factors remains unconsidered (Boin et al., Reference Boin, t Hart and McConnell2009b, p. 100; McGraw, Reference McGraw1990, p. 129). Perhaps most important, we do not know enough about the success prospects and consequences of different blame-generation and blame-management strategies in particular political and policy contexts. For example, whether and when particular blame-generation strategies lead to reputational damage, or even the resignations of incumbents, and whether and when they lead to policy change, be it fundamental or incremental, are questions largely unaddressed in existing work (Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2017, Reference Hinterleitner2018). In the next section of this chapter, I will advance the context-sensitive study of blame games by capturing these complex political events in a parsimonious, although comprehensive, framework.

2.2 A Theoretical Framework for the Analysis of Blame Games

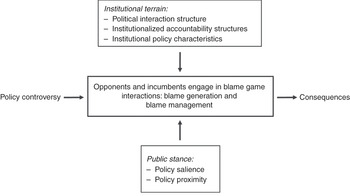

How can the interactions and consequences of a policy controversy-induced blame game be explained?1 In his classic book, The Semi-Sovereign People (Reference Schattschneider1975), E. E. Schattschneider defines the constitutive parts of political conflicts in a democracy. Since blame games are instances of intensified political conflict, I use these parts as the building blocks for my framework. Schattschneider envisions a political conflict as a fight between two parties. Interactions between the parties occur within and are influenced by the institutional terrain in which they are embedded. Crucially, in a democracy, important parts of the fight do not occur in the dark but rather in front of an audience. Considering these building blocks and their interrelations will reveal a lot about blame games and their consequences. Figure 1 illustrates the framework that will be developed in the following two sections. The first of these sections charts the institutional terrain in which a blame game is embedded, outlining how institutional factors influence the behavior of opponents and incumbents. The second section conceptualizes the relationship between the public and a blame game and outlines how the public’s attitude toward a blame game influences actors and their strategic behavior.

Figure 1 The theoretical framework for the analysis of blame games

Charting Institutional Terrain: Institutional Factors and Their Influence on Blame Game Interactions

Political conflict in democracies is governed by rules. As Albert Hirschman (Reference Hirschman1994, p. 212) famously put it, democracies must digest a “steady diet of conflicts” that constantly arise in modern societies. ‘Conflict management’, as he called this process, follows certain routines, which a political system institutionalizes over time (see also Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1975, p. 17). In the case of the analysis of blame games, this means that we must expose and describe the institutionalized forms of conflict management that political systems have developed to deal with policy controversies.

Before we set out to identify institutional factors, it is useful to develop an understanding of how these factors influence blame game interactions. During blame games, institutional factors emit both incentives for and constraints on political actors, channeling them toward particular actions while inhibiting others (Parsons, Reference Parsons2007; Streeck & Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005; Weaver & Rockman, Reference Weaver and Rockman1993). For example, when a policy controversy occurs in a particularly complex institutional landscape, far removed from the incumbent minister, it will be difficult for opponents to tie the controversy to the minister, and thus, they can only constrain their blaming on (mostly administrative) entities closer to the controversy. For the incumbent minister, on the contrary, a complex institutional landscape provides incentives to both diffuse blame within that landscape (because in a complex landscape many scapegoats are available) and to ride out the controversy (because political responsibility is opaque in complex landscapes). Therefore, institutional factors can be conceived as the rules of the game that structure blame game interactions (North, Reference North1990; Tsebelis, Reference Tsebelis1990). The framework treats institutional factors as exogenous structures that blame game actors must take as given during the temporal scope of the analysis (Parsons, Reference Parsons2007). In other words, actors cannot change institutional factors during the blame game.2

Due to the widespread neglect of context in the research on blame games, I pursue a syncretic approach in identifying relevant institutional factors, considering factors that have already been treated in the narrower literature on blame games and factors from the wider literature on political conflict. The guiding idea behind the selection of factors is that blame games are influenced by both the political arenas in which they are played out and by policy-related factors, since policies are an important component of the political terrain (Hacker & Pierson, Reference Hacker and Pierson2014).3 In the following, I identify three groups of institutional factors that chiefly influence blame game interactions: the political interaction structure, institutionalized accountability structures, and institutional policy characteristics. For each group of factors, I outline how their configurations in particular political systems influence blame game interactions. Table A1 in the Appendix contains an overview of the shapes of these institutional factors in the UK, German, Swiss, and US political systems.

Political Interaction Structure

Every democratic political system has institutionalized rules that structure competition between political actors during routine times. These rules are unlikely to completely lose their bite when political actors switch into a more conflictual mode of interaction (Capoccia, Reference Capoccia2016). The factors that I deem most important in this category are the organization of the opposition and the stance of governing parties. The organization of the opposition refers to whether the parliamentary opposition, which usually acts as the primary opponent in a blame game, is consolidated or rather fragmented in a political system. For instance, the parliamentary opposition in the UK or the USA consists of only one, or a maximum of two, major parties. In the German or the Swiss system, opposition parties are significantly more numerous. Opponents consisting of multiple opposition parties are likely to have trouble acting as a consolidated actor during a blame game (Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1997). Consolidated actors have an easier time coordinating attacks and devising a coherent narrative of a controversy. On the contrary, fragmented opponents are usually less successful in crafting a cohesive blame-generating strategy during a blame game because each party is likely to focus on the aspects of a controversy that they and their supporters deem most important. This should make it more difficult to keep blame pressure on incumbents high.

Along with the organization of the opposition, the stance of the governing party(ies) also influences blame game interactions. Namely, I expect that whether the parliamentary majority is loyal and actively supports the incumbent during a blame game should influence the actions of incumbents. Incumbents that receive support from their party(ies) can more successfully reframe a controversy. With their parties behind them, they can more credibly dismiss opponents’ blame attacks as instances of hypocritical vote-seeking behavior. Conversely, a government that confronts criticism from its own ranks or even a backbench revolt during a blame game is likely to have greater trouble downplaying a policy controversy because bipartisan criticism signals that the controversy is indeed problematic. This leads to the following expectations:

Expected effect of the political interaction structure on opponent behavior:

E1: Fragmented opponents, consisting of more than one party, are less successful in crafting a cohesive blame-generating strategy during the blame game than consolidated opponents.

Expected effect of the political interaction structure on incumbent behavior:

Institutionalized Accountability Structures

Every democratic political system has enshrined rules and norms that detail the responsibilities and duties of political actors (Bovens, Reference Bovens2007; Olsen, Reference Olsen2015). Responsibilities and duties determine who can be credibly involved in a blame game. Opponents can only expect to involve an actor if there is the slightest chance that they can establish a causal link between a policy controversy and that actor. In other words, there must be some sensible basis on which they can make claims of responsibility. Although the reasons behind a policy controversy may be multifaceted and belong to the distant past, a concrete implementation problem usually brings up a controversy. Therefore, administrative actors and entities are the ones who often get caught with their pants down when a controversy begins. During the course of a blame game, it is crucial that opponents can convey that incumbent politicians (and not just administrative actors and entities) bear personal responsibility for the controversy and must be held accountable.

Institutional factors that influence the assignment of responsibility usually take the form of conventions and doctrines of responsibility. Most political systems practice conventions of collective responsibility, such as collegiality principles, which make the government act as a consolidated actor during a blame game. Governments adhering to conventions of collective responsibility can usually, or at least in the beginning of a blame game, leave controversy management to the incumbent politician in whose specific domain the controversy occurred, while the government leader, as well as other government members, can hide behind that politician. As such, the individual politician in charge has a dual role during blame games. For opponents, they are the obvious gateway for blaming the government. For incumbents, they are a blame shield or lightning rod (Ellis, Reference Ellis1994) for the blame coming from opponents.

How much blame the politician receives and how good a blame shield they are for their government depends on conventions of resignation. These conventions detail which occurrences are grounds for the dismissal of individual politicians. In Westminster systems, for example, ministerial responsibility obliges ministers to take responsibility for the actions of their department, but the convention states that they only have to resign in cases of personal wrongdoings; a situation that is very unlikely during policy controversies (Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2015; Woodhouse, Reference Woodhouse2004). While prime ministers can freely make decisions about the fate of their ministers, they will rarely do so during a blame game, as taking a minister away amid blame attacks amounts to a plea of guilt or could be interpreted as a way of caving in. Therefore, conventions of resignation are very restricted in the UK. In Germany and the USA, such conventions are more extensive and vague, while in Switzerland, they are almost absent because federal councilors,4 although acting as the principals of their departments, are collectively responsible for controversies. The more extensive such conventions are, the more likely opponents are to concentrate their blaming on the incumbent politician, since extensive conventions allow opponents to formulate straightforward claims of responsibility for a broader range of actions. On the contrary, restrictive conventions are likely to decrease opponents’ incentives to involve incumbent politicians in a blame game because the range of issues for which they must resign is smaller. In the case of restrictive conventions, opponents can only blame administrative actors who are more directly involved in the controversy. Conventions thus not only influence whether or not an incumbent has to resign, but they also influence how much blame the incumbent receives in the first place, as opponents take incumbents’ attractiveness as blame targets into account.

By influencing the blaming behavior of opponents, conventions of resignation also determine how much is personally at stake for incumbent politicians during a blame game. Incumbent politicians who must comply with extensive conventions (and who thus receive more blame from opponents) will have greater difficulty defending themselves by reframing the controversy or deflecting blame for it than politicians who have to comply with restrictive conventions. Politicians who must comply with extensive conventions of resignation constitute worse blame shields and are more prone to suffer reputational damage during a blame game. This allows me to formulate the following expectations:

Expected effect of institutionalized accountability structures on opponent behavior:

E3: Opponents facing extensive conventions of resignation concentrate their blaming more on the incumbent politician than opponents facing restrictive conventions, who can only blame administrative actors.

Expected effect of institutionalized accountability structures on incumbent behavior:

E4: Incumbent politicians that must comply with extensive conventions of resignation have greater difficulty defending themselves during a blame game than politicians that must comply with restricted conventions.

Institutional Policy Characteristics

Since the government of the day carries the overall policy responsibility, it can theoretically be blamed for all policy controversies that erupt under its watch. What counts during blame games, however, is what can realistically be blamed on the government. And this, I suggest, primarily depends on the involvement of the government in a concrete policy issue. As Weaver (Reference Weaver1986, p. 390) already observed, the more incumbents appear to be directly involved in a policy issue (e.g., as architects, managers, or decision-makers), “the more likely they are to be held liable for poor performance.” However, direct government involvement is far from omnipresent in modern and complex political systems. ‘Agencification’ or New Public Management reforms adopted in many Western countries in recent decades led to the breakup of monolithic bureaucracies and distanced public-service provision from the direct control of politically responsible actors (Mortensen, Reference Mortensen2016; Verhoest et al., Reference Verhoest, van Thiel, Bouckaert and Lægreid2012). A significant share of policy controversies currently erupt in areas where a considerable number of public and private actors and entities are prominently involved in policymaking and implementation. This is good news for incumbent politicians. The complexity of collaborative structures that result from agencification reforms clouds the clarity of responsibility during a blame game (Bache et al., Reference Bache, Bartle, Flinders and Marsden2015; Hinterleitner & Sager, Reference Hinterleitner and Sager2017). In cases of low direct government involvement, opponents have greater difficulty pinning down blame on incumbents, while the latter can be expected to have less difficulty deflecting responsibility and blame onto administrative actors. In cases of direct government involvement, I expect that the stakes would be reversed. Opponents can more credibly blame political incumbents for a policy controversy, and the latter have much more difficulties credibly deflecting responsibility and blame onto administrative actors. This leads to the following expectations:

Expected effect of institutional policy characteristics on opponent behavior:

E5: Opponents are better able to blame a controversy on incumbents if the latter are directly involved than when the controversy is far removed from incumbents.

Expected effect of institutional policy characteristics on incumbent behavior:

E6: Incumbents are better able to deflect blame for a controversy onto administrative actors if they are not directly involved in the controversy rather than if they are involved.

Demonstrating the effects of political interaction structures, accountability structures, and institutional policy characteristics on blame-game interactions is a relatively straightforward task. As these institutional factors emit incentives and constraints on the actors involved in a blame game, one needs to show that their specific actions constituted rational responses to a particular institutional context while other actions were not feasible in that context (Parsons, Reference Parsons2007, pp. 62–64). For example, with regard to a policy controversy far away from the government, one needs to show that it would have been useless for opponents to lay the controversy at the door of political incumbents and that the only sensible choice was to blame administrative actors. Conceptualizing and demonstrating how the public’s stance toward a blame game impacts blame-game interactions requires a different approach, which I will present in the next section.

Listening to the Audience: Issue Characteristics and Their Influence on Blame Game Interactions

During a boxing match, most spectators do not stand idly by for long. They eventually take an active interest in the match and sympathize with one of the combatants. It is pretty much the same with blame games. When a blame game develops around a policy controversy, the public may watch that blame game and form an opinion on the severity of and responsibility for the controversy at the root of it. Or, the public might largely ignore that blame game, remaining uninterested about its details and indifferent with regard to questions of severity and responsibility. Whether the public watches a blame game or largely ignores it has profound implications for blame game interactions. A public that watches a blame game encourages opponents to expand their blaming efforts and drag it on. Incumbents who feel the heat from the public are likely to realize that they must do something to address the controversy and engage in blame management. An indifferent public, on the contrary, makes opponents quickly realize that their initial blame-generating attempts are futile. Accordingly, they should quickly desist from exploiting the controversy and pay mere lip service to its resolution. Incumbents, in turn, can then adopt a laid-back and uncompromising stance toward the controversy. These stylized scenarios suggest that the public’s stance importantly influences blame-game interactions. In order to fully understand blame games, we must thus “keep constantly in mind the relations between the combatants and the audience” (Schattschneider, Reference Schattschneider1975, p. 2).

But what is it that makes publics watch one blame game while ignoring another? Policy feedback theory and literature on problem construction shows that the public cares about policies (including their changes and controversies) in differentiated ways and to varying degrees (e.g., Mettler & SoRelle, Reference Mettler, SoRelle, Sabatier and Weible2014; Pierson, Reference Pierson1993; Rochefort & Cobb, Reference Rochefort and Cobb1994). Since the analysis of political information “is costly in time and foregone opportunities,” publics usually only spend a little time forming an opinion on particular issues (Page & Shapiro, Reference Page and Shapiro1992, p. 14; Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). Therefore, one must identify the characteristics that make policy controversies protrude from the abundance of mass-mediated events. I suggest that the salience of a controversy and its proximity to the public are crucial in this regard (Hinterleitner, Reference Hinterleitner2018). These characteristics determine the public’s answer to two distinct questions regarding a controversy: first, does the public care and, second, is it directly affected by the controversy?

Controversies can be considered salient if they are particularly severe or novel, or if they touch core values that the public holds dear (Brändström & Kuipers, Reference Brändström and Kuipers2003; Mettler & Soss, Reference 241Mettler and Soss2004). On the contrary, controversies that are long-standing or recur frequently, or which only produce material costs (instead of ideational costs) can be considered to be nonsalient. Publics can be expected to care much more about salient controversies than about minor or frequently recurring ones. Proximity captures the extent to which a controversy directly affects the public, that is, whether the controversy “exists as a tangible presence affecting people’s lives in immediate, concrete ways” (Soss & Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007, p. 121). In other words, proximity concerns the distribution of material costs. Since proximate controversies activate considerations of self-interest (Campbell, Reference Campbell2012; Page & Shapiro, Reference Page and Shapiro1992, pp. 339–340), they are likely to attract much more public interest and evaluation of their consequences than controversies whose consequences are only felt in the distant future or must be shouldered by a small portion of the overall public (especially if the latter is politically weak). I argue that salience and proximity are the most important issue characteristics for assessing the relationship between blame game actors and the public during a blame game.

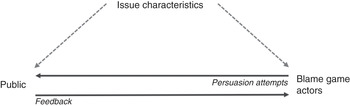

In order to fully understand the relationship between the public and blame game actors, we must also take into account that public feedback does not only emerge from the policy controversy as such, but it is also distorted by the communication attempts of the participants in the blame game (Béland, Reference Béland2010; Patashnik & Zelizer, Reference Patashnik and Zelizer2013). Blame games are mass persuasion situations (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992), during which opponents and incumbents send conflicting messages to publics so as to draw them on their side. In doing so, they work with and are constrained by issue characteristics. In other words, opponents and incumbents try to exploit salience and/or proximity, or the absence of these characteristics, for their purposes. When opponents aim to direct the public’s attention to a controversy and persuade it that what it sees is indeed a venerable crisis, they can emphasize particularly salient or proximate aspects of that controversy. When incumbents try to convince the public that a controversy is just a minor incident that does not merit further public attention, they can try to reframe particularly salient aspects of a controversy or, if possible, use the distance of the controversy to downplay its negative effects. Issue characteristics are constructs that opponents and incumbents can accentuate and exploit in order to persuade the public of their interpretation of a controversy. If these persuasion attempts are successful, the public will adopt the interpretation of the controversy presented by either opponents or incumbents (Boin et al., Reference Boin, t Hart and McConnell2009b).

However, when opponents and incumbents try to pull the public on their side, they do not face an anything goes situation. Rather, the direct influence of issue characteristics on the public constrains them. Opponents are unlikely to convincingly portray a controversy as salient when the public does not really care about it, for example, because it has seen numerous controversies of a similar sort and has thus become used to them. Neither should incumbents be able to successfully frame a controversy as distant when its impact on large parts of the public is obvious. For instance, incumbents will most likely have difficulties portraying a large-scale public health scandal that potentially threatens everybody as distant. For incumbents and opponents, issue characteristics are malleable, but only to a certain extent. The dashed arrow leading from issue characteristics to the public in Figure 2 captures this constraint. It expresses the idea that the public has preconceived ideas about most controversy types that notably influence public feedback to a controversy. This conceptualization of the relationship between the public and blame game actors reveals a notable difference between the two main categories of explanatory factors outlined in the theoretical framework. While the causal relationship between institutional factors and blame game actors is unidirectional (because blame game actors cannot change institutional structures during the blame game), the relationship with the public is reciprocal (because blame game actors try to work with issue characteristics to influence the public). Figure 2 summarizes this relationship and the influence of issue characteristics on the relationship’s concrete shape.

Figure 2 The relationship between the public and the blame game

Before I formulate expectations about what the relationship between the public and blame game actors looks like for different combinations of salience and proximity, three complications must be considered. First, the public, in reality, consists of a spectrum of varying attention to an issue (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992). What one part of the public perceives as salient may be interpreted as nonsalient by other parts. Likewise, controversies may be proximate to some parts of the public while appearing distant to others. This aspect requires that I simplify the empirical analysis and assess whether the majority of the public perceives a controversy as salient and proximate (Soss & Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007).

Second, the public and blame game actors do not communicate directly, rather they do so through the media. On the one hand, the media conveys the public’s attitude toward a blame game by covering the issue more or less intensively and excitedly. On the other hand, it transmits communication attempts to the public from opponents and incumbents, as well as background information on a controversy. While pursuing this task, the media does not act as a neutral transmitter but more like a catalyst driven by profit motives.5 While the media systems of modern democracies differ on a number of dimensions (Hallin & Mancini, Reference Hallin and Mancini2004), they are pretty similar when it comes to their role as catalyst during a blame game. Media systems have mostly converged on the increased commercialization and associated popularization of political news coverage (Umbricht & Esser, Reference Umbricht and Esser2016). This development allows me to reasonably assume that the media plays a largely similar role across Western political systems in terms of blame game coverage and scandalization. The media is both a watchdog and a scandalization machine (Allern & von Sikorski, Reference Allern and von Sikorski2018). Both roles make the media intensively cover the policy controversies that are either very severe or have significant scandal potential.

Although the media’s role as a catalyst further complicates the relationship between the public and blame game actors, it also offers the opportunity to measure public feedback to a blame game. Polls held by news agencies would be ideal for measuring public feedback to a blame game. Unfortunately, suitable polls are often scarce. A lack of first-hand information on the public’s reaction does not carry too much weight, however, because blame game actors, just like researchers, cannot peer into the heads of citizens but must work with what the media conveys during a blame game. Therefore, by considering the amount, the tone, and the variation of the media coverage of a blame game and the public statements of blame game actors, one can obtain a sufficiently clear picture of how blame game actors react to the public. While tabloids predominantly cover a blame game in a scandalizing fashion, quality papers also inform their audience about the underlying policy controversy and report on the blame game in a more problem-oriented way. If there is not only significant quality coverage of a blame game, but also a significant amount of tabloid coverage, one can safely assume that the wider public – and not just the societal elite – is watching the blame game. Moreover, since tabloids are very scandal-driven, they allow me to clearly measure what exact aspect of a policy controversy is considered to be scandalous.6 In general, the tone of the coverage discloses whether a controversy is perceived to be salient or not. Personalized and emotional coverage signals that the public perceives a controversy to be salient while problem-oriented and unemotional coverage indicates that a controversy is perceived to be nonsalient. Finally, a look at variations in coverage between left-leaning and conservative outlets helps to control for political parallelism.7

A final complication is that the relationship between the public and blame game actors cannot be captured by adopting a snapshot perspective because, during a blame game, the relationship may become distorted by other political events. For example, strong public feedback to a particular blame game may abruptly be suppressed by a natural disaster or by a severe foreign policy crisis. Another possibility is that opponents only receive weak feedback following their blame-generating attempts on the occasion of a controversy, but that in light of upcoming elections, they decide to nevertheless drag the blame game on. In the empirical analysis that follows, I will account for these distortions by assessing situational factors, such as looming elections or simultaneous, attention-attracting political events. Before, however, I will flesh out the relationship between the public and blame game actors against the backdrop of a distant-salient controversy, a proximate-nonsalient controversy, and a distant-nonsalient controversy.

Distant-salient controversies “elicit rapt attention and powerful emotion, but their design features and material effects slip easily from public view because they lack concrete presence in most people’s lives” (Soss & Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007, p. 122). Because most distant-salient controversies relate to issues of justice and fairness, the public feedback to them is predominantly based on moral considerations. For opponents, a public that passionately watches the ensuing blame game creates strong incentives to invest in blame generation. In such a case, opponents are likely to make the controversy bigger than it is, as the public is less able to evaluate the implications of distant controversies than those of proximate ones. Moreover, opponents can be expected to try to damage incumbents on moral grounds by portraying them as unfaithful leaders. Incumbents should take a distant-salient controversy very seriously. Strong blame pressure from opponents makes it difficult for them to keep out of the ensuing blame game. In an emotionalized atmosphere, they are unlikely to successfully reframe the controversy and, therefore, should concentrate on blame deflection and symbolic actions that signal their willingness to address the controversy. This is summarized in the following expectations:

Expected opponent behavior against the backdrop of a distant-salient controversy:

E7: Opponents strongly invest in blame generation on the occasion of a distant-salient controversy and attempt to damage incumbents on moral grounds.

Expected incumbent behavior against the backdrop of a distant-salient controversy:

E8: Incumbents take a distant-salient controversy very seriously and confront it by engaging in blame deflection and symbolic activism.

Proximate-nonsalient controversies affect a large share of the public, but they are not very salient in public discourse, as their impacts are often difficult to grasp or because they do not trigger much anger or emotion among the public. Nevertheless, a controversy of this type is likely to generate stronger public feedback “than one would expect based on the policy’s low salience alone” (Soss & Schram, Reference Soss and Schram2007, p. 122). Due to its proximity, feedback should be primarily based on considerations of self-interest. Opponents confronting a public that attentively watches the ensuing blame game can be expected to try to exploit the proximity of the controversy and invest considerably in blame generation, mainly by activating considerations of self-interest among the public. Incumbents, in turn, do not confront a heated environment, like when they have to address a salient controversy, but they can still not afford to just lay back and mainly ignore the issue. While they are likely to signal that they take the controversy seriously, they may also try to reframe it and eventually engage in activism to eliminate the negative consequences emanating from the controversy. This leads to the following expectations:

Expected opponent behavior against the backdrop of a proximate-nonsalient controversy:

E9: Opponents invest considerably in blame generation on the occasion of a proximate-nonsalient controversy and try to activate considerations of self-interest among the public.

Expected incumbent behavior against the backdrop of a proximate-nonsalient controversy:

E10: Incumbents take a proximate-nonsalient controversy seriously and address it by mainly adopting reframing strategies and forms of activism.

Distant-nonsalient controversies do not usually attract much public attention, as they neither arouse emotions nor directly affect the wider public. Citizens may consider them as elite issues that lack implications for ordinary citizens, or have heard of these controversies so frequently that they have become used to them. Accordingly, public feedback to these controversies is likely to be weak. For opponents, a controversy that is largely ignored by the public is an inappropriate occasion for damaging the reputation of incumbents or for changing the trajectory of a policy. Opponents should thus not invest much in blame generation but should rather quickly desist from pursuing the controversy and pay mere lip service to its resolution. Incumbents, on the other hand, are unlikely to feel threatened by a distant-nonsalient controversy. They can be expected to ignore the controversy for as long as possible, only scarcely engage in blame management, and even adopt an uncompromising stance with regard to its resolution. This allows me to formulate the following expectations:

Expected opponent behavior against the backdrop of a distant-nonsalient controversy:

E11: Opponents do not invest much in blame generation on the occasion of a distant-nonsalient controversy.

Expected incumbent behavior against the backdrop of a distant-nonsalient controversy:

E12: Incumbents do not take a distant-nonsalient controversy very seriously and only scarcely engage in blame management.

In the next five chapters of this book, I test the explanatory potential of this framework by applying it to different blame games that occurred in the UK, Germany, Switzerland, and the USA. Before we delve into the analysis of blame games, however, a last remark on the explanatory logics that underlie the framework is in order. As already explained, the framework treats institutions as exogenous and unalterable structures that opponents and incumbents must take as given during a blame game. Issue characteristics, on the contrary (and rather counterintuitively), are treated as institutions that opponents and incumbents can manipulate, although only to a certain extent. Conceiving the influence of institutions and issue characteristics in this way implies objective rationality on the part of opponents and incumbents because they can be expected to react regularly and reasonably to the external constraints that emanate from structures and institutions (Parsons, Reference Parsons2007). The next chapters will demonstrate that this approach allows for parsimonious and crisp explanations of blame game interactions.