2.1 Cities in the Context of the Anthropocene

In this chapter, we argue for the need to take a complex systems approach to understand urbanization and its impacts based on its key variables and drivers: agents, emergence, self-organization, and criticality. A complex systems approach will necessitate a shift from viewing cities only as social-technological systems to viewing them also as social-ecological systems and, even further, as complex social-ecological-technological systems, or SETs (McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Pickett, Grimm, Niemelä, Alberti and Elmqvist2016a; Depietri and McPhearson, Reference Depietri, McPhearson, Kabisch, Korn, Stadler and Bonn2017), involving the interactions and coevolution of social systems, living systems, and built systems.

Cities are one of the most distinctive features of the Anthropocene – a new geologic epoch characterized by the dominant influence of humanity on the environment – yet one of the least understood Earth systems. Philosophers have been curious about how cities emerge and function since the first appearance of human settlements 10,000 years ago, but both formal conceptualization and study of urban systems are more recent (Geddes Reference Geddes1915; Mumford Reference Mumford1961; Park 1925; Lynch Reference Lynch1961; Forrester Reference Forrester1969; Jacobs Reference Jacobs1969; Hall 1998). Over the last century, scholars in a broad array of disciplines have advanced various theories to explain urban dynamics. Such theories have evolved separately, in discrete domains, for more than a century, and strongly reflect a view of humans and natural systems as essentially separated from each other. Conceptualizations have commonly preceded attempts to study such systems empirically. The emergence of a new urban ecology beginning in the late 1990s represents the first significant attempt to integrate a diversity of approaches from a broad set of disciplines to advance understanding of cities as complex, coupled human-natural systems (Pickett et al. Reference Pickett, Wu, Cadenasso and Walker1999; Grimm et al. Reference Grimm, Grove, Pickett and Redman2000; Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Marzluff, Shulenberger, Bradley, Ryan and Zumbrunnen2003; Grimm et al. Reference 64Grimm, Faeth, Golubiewski, Redman, Wu, Bai and Briggs2008; Alberti Reference Alberti2016; Bai Reference Bai2016; McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Pickett, Grimm, Niemelä, Alberti and Elmqvist2016a).

Earlier theories of cities have been useful for describing a variety of urban phenomena, but cannot provide a general explanation of how cities emerge, persist, or collapse. The development of complexity theory has enabled scholars to begin asking such questions and making sense of various aspects of city function and dynamics. Cities across the globe exhibit unique patterns visible from space (Figure 2.1), reflecting diverse socioeconomic and biophysical characteristics, as well as their history and stage of development (Bai and Imura Reference Bai and Imura2000; Bai Reference Bai2003). Yet, the emerging patterns hint at universal principles of emergence, growth, and evolution of cities. We can ask: What do cities have in common, regardless of their geographical location and size? And which elements are specific to historical or geographic circumstance? Are there underlying mechanisms and universal laws of urban evolution (Bettencourt et al. Reference Bettencourt, Lobo, Helbing, Kuhnert and West2007; Batty Reference Batty2008)? As urban scientists have introduced mathematical rigor to the exploration of common urban properties across the world’s cities and high resolution data have become increasingly available, we begin to discover new insights for planning and policy-making. Yet the application of complex models and empirical explorations remain at an early stage (McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Haase, Kabisch and Gren2016b). Urban ecology advances the need of a science of cities as coupled human-natural systems.

Figure 2.1 Cities’ patterns from space. NASA City Night Lights 1) New York City, 2) Paris, 3) Cairo, and 4) Tokyo.

2.2 The City as a Complex System

As major drivers of global change, cities have a prominent role in enabling the Earth’s transition to sustainability (see Chapter 1). Understanding the complex dynamics linking urban changes to social-ecological-technical change is critical to gaining new insights for the future of ecological and human well-being.

2.2.1 Agents

Cities are characterized by complex interactions among multiple heterogeneous agents and components across multiple scales. Agents are members of households, individual businesses, real estate developers, local and regional governments, nonprofit organizations, and academic institutions that make a variety of decisions affecting resources and land use. These agents are highly heterogeneous within and across cities and their decisions. Empirical evidence suggests that household residential location choices (Waddell 2013) or landscape management practices (Polsky et al. Reference Polsky, Grove, Knudson, Groffman, Bettez and Cavender-Bares2014) are influenced by their diverse characteristics, perceptions, and preferences. These decisions directly and indirectly affect the biophysical system through land conversion, exploitation of resources, and generation of emissions and waste. Businesses make decisions about production, location, and management practices. Members of households make choices about employment, residential location, housing type, travel mode, and other activities. Real estate developers make decisions about housing development and redevelopment. Governments shape urban resource flows and environmental impacts about investing in infrastructures and services, as well as adopting policies and regulations that influence agents’ interactions and the decisions they make (Bai Reference Bai2016). Decisions are made at the individual, community, city, and regional levels through both economic and social institutions.

2.2.2 Emergence

In cities and urbanizing regions, agents interact dynamically within communities and through social networks, economic markets, and many public institutions (including governmental and other nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations), giving rise to emergent properties. It is through these multiple interactions across time and space that urban agents generate observable emergent physical (for example, sprawl), behavioral (for example, travel), social (for example, neighborhood segregation), economic (for example, income, real estate values), ecological (for example, biodiversity), and environmental (for example, atmospheric pollution) patterns.

Urban segregation and inequality are examples of emergent patterns resulting from dynamic interactions among many agents and social groups and their residential choices which, in turn, are simultaneously influenced by personal preferences, job markets, land and real estate markets, and public policies and investments (Box 1.1). Emerging contemporary patterns of urban segregation are far more complex than typically represented by the average center-periphery pattern of early urbanization. In Brazilian cities, for example, Feitosa (Reference Feitosa2010) shows how political and socioeconomic changes that occurred in the 1980s significantly altered the patterns of urban segregation and the dynamic interactions that govern urban spatial configurations. The poor were not able to afford dwellings in the “legal city” or to build houses in irregular settlements (do Rio Caldeira Reference do Rio Caldeira2000; Torres et al. Reference Torres, Marques, Ferreira and Bitar2002). Instead, they initiated the proliferation of favelas in central areas even closer to wealthy neighborhoods. The emergent pattern challenges the spatial duality and socioecological homogeneity of urban spaces – the traditional allocation of affluent families in central neighborhoods, with poor families pushed to the peripheries – by diffusing and intermixing favelas located in different regions of the city, including those closer to wealthy neighborhoods (Torres et al. Reference Torres, Marques, Ferreira and Bitar2002).

Multiple feedback mechanisms between urban segregation and individual choices reinforce such patterns. Urban segregation has consistently led to negative consequences for the lives of urban inhabitants by reinforcing social exclusion, concentration of poverty, limited access to natural resources, environmental degradation, and greater exposure to environmental risks. As a result, segregation and institutionalized inequality substantially affects the capacity of cities to contribute to social and economic development (Sabatini et al. Reference Sabatini, Caceres and Cerda2001; Torres et al. Reference Torres, Marques, Ferreira and Bitar2003).

2.2.3 Self-Organization

As cities grow, they increase in complexity, yet such complexity is not fully guided or managed by an outside source; this development is self-organizing. In self-organizing systems, patterns and organization develop through interactions internal to the system. In Self-Organization and the City, Portugali (2002) introduces the notions of stability and instability across scales. Building on the example of urban segregation, the emergence of slums can be seen as the emergence of instability pockets essential to ensure global stability of the urban system (Portugali Reference Portugali2000; Barros and Sobriera Reference Barros and Sobriera2002). But a more in-depth examination uncovers the emergence of slums – traditionally considered to be and defined as “informal settlements” – as a complex socioecological phenomenon: the social production of habitat resulting from social exclusion (Zárate 2016).

Complexity and self-organization pose challenges to the dominant planning paradigm. Despite the increasing attention of planning scholarship to resilience science, planning practice has just begun to incorporate resilience principles and to move away from a steady-state approach and a view of planning as an outside agent controlling and directing urban change. There is an inherent tension between the self-organization properties of complex socioecological systems and the idea of planning towards a desirable societal goal. Transforming such tension towards a novel planning paradigm might be key to advancing both the discipline and the practice. Self-organization has important implications for the way systems evolve (Jorgenson Reference Jorgensen1997; Phillips Reference Phillips1999). Yet, various theories draw different conclusions. Phillips (Reference Phillips1999) suggests that the key question is how divergent self-organization and patterns are linked to instability and chaos, and how, together, they affect system evolution. The extent to which cities are self-organized and how this drives system dynamics is critical to understanding how to intervene in this complexity to achieve desirable goals for urban societies.

2.2.4 Criticality

Self-organized systems are at a critical state – a state in which perturbations are propagated over long temporal or large spatial scales (Bak Reference Bak1996). Such systems exhibit scale-invariance characteristic of the critical point (or attractor towards which a system tends to evolve) of a phase transition. An example is a sand pile in which local interactions result in frequent, small avalanches and infrequent large ones. In such systems, transitions can be triggered by external forces or internal changes in system feedbacks. Such “phase transitions” may be triggered by unpredictable external events, but often they result from endogenous underlying processes that maintain their stability and resilience.

There is increasing evidence indicating that major transitions in financial systems and ecosystems are typically preceded by gradual change in internal processes until they reach a threshold: a small external perturbation can trigger a domino effect that propagates through the system and causes a shift to a new state (Sheffer et al. Reference Sheffer, Hardenberg, Yizhaq, Shachak and Meron2013).

There are several documented examples of regime shifts in ecological systems: in lakes, coral reefs, oceans, and forests (Scheffer et al. Reference Scheffer, Carpenter, Foley, Folke and Walker2001). The literature also documents examples of regime shifts in human societies both in prehistoric human societies, such as Easter Island (Flenley and King Reference Flenley and King1984), and more recent examples across multiple regions of the world (Kinzig et al. Reference Kinzig, Ryan, Etienne, Allison, Elmqvist and Walker2006). But how the coupling between human and environmental systems adds to such complex dynamics is not fully understood (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Dietz, Carpenter, Alberti, Folke and Moran2007). In such systems, further nonlinearities affect the interactions between external and internal conditions and drive the system to a critical threshold that might cause a regime shift and/or system reorganization (Holling Reference Holling1973).

Hurricanes Sandy and Katrina clearly illustrate the unexpected shocks cities are likely to face in the next decades; both storms were a result of increasing climate extremes driving fast variables (that is, storm formation) and interacting with the slow, variable processes of wetland loss; increased human and infrastructure vulnerabilities associated with land cover change (that is, coastal development); transportation, housing, and energy sector vulnerabilities; and the build-up of system complexity over time (Sanderson et al. Reference Sanderson, Solecki, Waldman and Parris2016; Blum and Roberts Reference Blum and Roberts2009).

2.2.5 Biodiversity and Urban Areas as Socioecological Systems

Emergent patterns of biodiversity in cities illustrate the complex socioecological dynamics of urban ecosystems. Humans are affecting the abundance and distribution of species across the planet, and these impacts are projected to increase in this century (Pereira et al. Reference Pereira, Leadley, Proença, Alkemade, Scharlemann and Fernandez-Manjarrés2010; Pimm et al. Reference Pimm, Jenkins, Abell, Brooks, Gittleman, Joppa, Raven, Roberts and Sexton2014). The expansion of cities will triple urban land cover by 2030, compared to 2000, and will occur in areas of significant biodiversity hotspots (Seto et al. Reference Seto, Güneralp and Hutyra2012; see also Section 1). The future of urban biodiversity will depend on how cities spread, but also on socioecological interactions and on how habitat is preserved within cities. Attention to habitat size and connectivity will maintain not only species, but ecosystem processes and the evolutionary processes that allow adaptation and diversification within cities (Loreau et al. Reference Loreau, Mouquet and Gonzalez2003).

Urbanization transforms the biophysical structure of the landscape, which contributes to biodiversity change both directly within cities (McKinney Reference 65McKinney2008; Elmqvist et al. Reference Elmqvist, Fragkias, Goodness, Güneralp, Marcotullio and McDonald2013; Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, La Sorte, Nilon, Katti, Goddard and Lepczyk2014) as the expanding built environments alter habitat quality and connectivity, and at much larger scales as it indirectly drives habitat loss through trade demands for food and resources (Seto et al. Reference Seto, Güneralp and Hutyra2012). Cities also constitute habitat for many species. Many anthrophilic species do well in urban environments, and trends in the diversity of these species may increase as urban land cover increases (Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Handel, La Puma and Clemants2015).

Aronson et al. (Reference Aronson, La Sorte, Nilon, Katti, Goddard and Lepczyk2014) compared 54 cities and found that the density of bird and plant species (number of species per km2) in cities has declined substantially: only 8 percent of native bird and 25 percent of native plant species are currently present compared with estimates of nonurban densities of species. Aronson et al. (Reference Aronson, La Sorte, Nilon, Katti, Goddard and Lepczyk2014) found that the density of species in cities and the loss of density of species was best explained by land cover and city age rather than by nonanthropogenic factors (such as geography and climate).

Beninde et al. (Reference Beninde, Veith and Hochkirch2015) conducted a meta-analysis of the factors mediating intra-urban bird, insect, and plant species richness across 75 cities worldwide. Their focus was on within-habitat species richness as opposed to city-scale species richness. They found that habitat patch areas and corridors (connected linear strips of habitat) have the strongest positive effects on species richness, along with vegetation structure. Large habitat patches of greater than 50 hectares in size are necessary to prevent the loss of area-sensitive species in cities. They only analyzed data for corridors from two cities, but the effects were marked for multiple taxa. Functional connectivity is vital to increasing the effective area of urban habitat, so networks of corridors are likely to help biodiversity conservation in cities (Rayfield et al. Reference Rayfield, Pelletier, Dumitru, Cardille and Gonzalez2015; Albert et al. Reference Albert, Rayfield, Dumitru and Gonzalez2017).

Our most complete data on urban biodiversity are from European and North American cities. We expect to find similar patterns of biodiversity change in cities in Asia and Africa, but monitoring is required to establish whether similar patterns of change will be observed over the coming century. Widespread adoption and implementation of a common indicator set, such as the City Biodiversity Index (Kosaka et al. 2013), will further foster comparisons across cities. Biodiversity is integral to the ecosystem services that benefit people in urban environments (such as microbial diversity, which influences human immune system health (Rook Reference Rook2013); as such, these monitoring programs would also reveal how changes in biodiversity affect the quality of ecosystem services.

2.2.6 Adaptation and Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics of Biodiversity

Evidence that cities drive microevolutionary change poses new challenges for the study of urban sustainability (Palkovacs et al. Reference Palkovacs, Kinnison, Correa, Dalton and Hendry2012; Alberti Reference Alberti2015; Alberti et al. 2017a). By examining more than 1,600 observations of phenotypic change in species across the globe, Alberti et al. (2017a) were able to detect a clear urban signal. Examples of phenotypic changes driven by urbanization have been documented for many species of birds, fish, plants, mammals, and invertebrates (Yeh and Price Reference Yeh and Price2004; Carlson et al. Reference Carlson, Quinn and Hendry2011; Haas et al. Reference Haas, Blum and Heins2010; Cheptou et al. Reference Cheptou, Carrue, Rouifed and Cantarel2008; Jacquemyn et al. Reference Jacquemyn, De Meester, Jongejans and Honnay2012; Alberti et al. 2017b). Humans in cities affect species composition and their functional roles by selectively determining phenotypic trait diversity and causing organisms to undergo rapid evolutionary change. Changes in individuals, populations, and communities have cascading effects on ecosystem functions and human well-being, including biodiversity, nutrient cycling, seed dispersal, food production, and human health (Alberti Reference Alberti2015).

Several scholars of urban ecology are exploring the link between phenotypic change and their effects on ecosystem functions in urbanizing regions (Marzluff Reference Marzluff2012; Donihue and Lambert 2014; Alberti Reference Alberti2015; Alberti et al. 2017a). The emergence of eco-evolutionary feedbacks on contemporary time scales (Pimental Reference Pimentel1961; Schoener Reference Schoener2011) might affect ecosystem productivity and stability of cities (Matthew et al. Reference Matthews, Narwani, Hausch, Nonaka, Peter, Yamamichi and Sullam2011). For example, the physical structure of estuarine and coastal environments is maintained by a diversity of organisms, particularly dune and marsh plants, mangroves, and seagrasses. Evolution in traits underlying their ecosystem-engineering effects has potentially significant functional impacts on coastal cities’ resilience. Other examples of ecosystem functions relevant to both ecosystem and human well-being include nutrient cycling and primary productivity regulated by consumers’ traits, which control their demand for resources. Understanding the mechanisms by which human agency affects evolutionary feedback is critical to anticipating future evolutionary trajectories in cities.

2.2.7 Resilience

One important attribute of a complex system is resilience, which, for cities, can be translated to the ability to maintain human and ecosystem functions simultaneously over the long-term (Alberti and Marzluff Reference 62Alberti and Marzluff2004; see also Chapter 7). In cities, ecological and human functions are interdependent. Urban sprawl can cause rapid shifts in the quality of natural habitat, from a well-connected natural land cover to a state in which the natural land cover is greatly reduced and highly fragmented (Dupras et al. Reference Dupras, Alam and Revéret2015). Sprawl is a dynamic gradient of urban land cover that results when urban dwellers and real estate developers operate without taking into account the full social and ecological costs of providing human services to low-density development (Alberti and Marzluff Reference 62Alberti and Marzluff2004).

Patterns of urban development and infrastructure play a key role in maintaining the capacity of urban regions to adapt in the face of urban growth and environmental change. For example, we know that urban sprawl drives loss of forest cover and natural habitat and threatens biodiversity (Elmqvist et al. Reference Elmqvist, Fragkias, Goodness, Güneralp, Marcotullio and McDonald2013). The amount of impervious surface and the density of roads is associated with loss of ecological integrity of streams, and hydrological changes associated with urbanization and shoreline hardening increase the vulnerability of coastal cities to floods. Yet, we do not know how different urban forms, densities, land-use mix, and types of infrastructures affect the diverse ecological processes that affect ecological conditions and human well-being. Nor do we fully understand the trade-offs associated with different housing or infrastructure alternatives (Alberti Reference Alberti2010). New patterns of urbanization pose additional challenges to characterizing mismatches between supply and demand of ecological goods and services that require cross-boundary and cross-scale considerations (Kremer et al. Reference Kremer, Hamstead, Haase, McPhearson, Frantzeskaki and Andersson2016; McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Andersson, Elmqvist and Frantzeskaki2015).

Resilience in urbanizing regions depends on variable biophysical and socioeconomic conditions as well as stage of urban development; resilience in a city and its surrounding region is highly affected by its infrastructure. Cities provide unique opportunities to rethink and establish novel, integrated infrastructure systems such as, sustainable energy systems that rely on renewable energy sources (Kammen and Sunter Reference Kammen and Sunter2016). Technological developments, in turn, have the potential to influence future urban trajectories. Using two cases of large hydraulic works in the Dutch delta, van Staveren and van Tatenhove (Reference van Staveren and van Tatenhove2016) illustrate how past technological interventions can profoundly shape the direction in which deltas develop.

2.3 Urban Social-Ecological-Technical Systems and Innovation

Advancing social-ecological conceptual frameworks for understanding complex dynamics of urbanization requires explicitly representing the built infrastructure and technological components of urban systems (Ramaswami et al. Reference 66Ramaswami, Chavez and Chertow2012; McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Pickett, Grimm, Niemelä, Alberti and Elmqvist2016a; Depietri and McPhearson, Reference Depietri, McPhearson, Kabisch, Korn, Stadler and Bonn2017) and the relative change in urban metabolism that their development implies (Kennedy et al. Reference Kennedy, Cuddihy and Engel-Yan2007; Kennedy et al. 2009). More recent studies attempt to provide conceptual bridges between urban metabolism and urban ecosystem studies (Bai Reference Bai2016). Cities depend on larger-scale built infrastructures (such as electric power, water supply, and transportation networks) that sustain flows of resources over large distances. The new, emerging patterns of urbanization (including city regions, urban corridors, and mega-regions) result from the evolution of technology and generate new demand for infrastructure systems that require further technological innovation. Urban regions operate as hubs of global and regional flows of people, capital, services, and information that drive the global economy (Sassen Reference Sassen2012). Yet, the rapid socioeconomic and environmental changes cities are both causing and experiencing pose new challenges to infrastructure systems, exacerbated by the inability of many cities to keep pace with rapid urban growth and the lack of appropriate institutional and governance structures to respond to emergent problems.

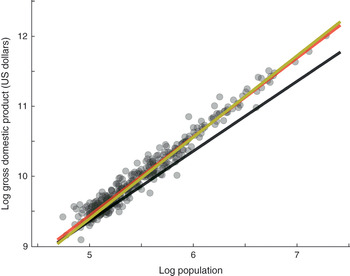

Transitions in complex systems pose great challenges to system stability and resilience, but are also an important source of novelty and transformation (Alberti Reference Alberti2016). While cities are often associated with poverty concentration, slum proliferation, and social and environmental problems, they have also traditionally been the centers of economic growth and innovation. Urban areas house 54 percent of the global population and generate more than 70 percent of global GDP (UN-Habitat 2016). Empirical data across many cities show that close interactions among diverse people in cities foster collaborative creativity and the capacity to innovate. Recent studies have explored the relationships between important measures of outputs from socioeconomic processes in cities and population size, providing ample evidence that important properties of cities of all sizes increase, on average, faster (socioeconomic superlinearity) or slower (material infrastructure sublinearity) than city population size (Bettencourt 2013). Bettencourt et al. (2010) found that income and innovation change in a consistently superlinear manner (with exponent β ~1+ 1/6) in response to growth, showing increasing returns, while infrastructure responds sublinearly (β ~ 1–1/6), suggesting economies of scale in material infrastructure relative to population growth (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 The scaling of gross domestic product as a function of city population.

To explain why the emergent patterns observed in cities are a special case of complex natural systems, Bettencourt (2013) compares cities to stars. Cities attract people and accelerate social interaction and social outputs in a manner that is analogous to the way in which stars compress matter and burn brighter and faster with increased size. Social interactions – efficient social networks, embedded in space and time, that evolve – make the city a new phenomenon in nature. Yet, in spite of a city’s fast pace and rapid evolution, achieving sustainability depends not only on the ability to innovate, but also on the type of innovation that is performed.

As centers of innovation, cities have the potential to play a prominent role in reorienting patterns of urbanization and infrastructure towards sustainability – for example, through integrated renewable energy systems (McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Parnell, Simon, Gaffney, Elmqvist and Bai2016c). Yet, innovation and novelty are part of a tightly coupled system of socioeconomic and environmental drivers mediated by both built infrastructure and technological systems. For example, the generation and adoption of efficient technologies (including those that relate to energy, water, and CO2 emissions) are driven by a complex interplay between increasing social interactions (such as social networks), the quality of urban ecosystems, and increasing environmental changes (such as extreme climatic events), but also by the vulnerability and resilience of the city to these changes. In cities, the built infrastructure and natural infrastructure play critical roles in reducing vulnerability, mitigating hazards, and responding to disasters. Technological innovation and its diffusion depend on socioeconomic conditions, urban development policies, and institutional capacity. Scholars have begun to explore the relationships between emerging novel governance and management systems and socioecological innovation (Walker et al. Reference Walker, Holling, Carpenter and Kinzig2004; Chapin et al. Reference Chapin, Carpenter, Kofinas, Folke, Abel and Clark2010; Folke et al. Reference Folke, Carpenter, Walker, Scheffer, Chapin and Rockström2010; Westley et al. Reference Westley, Olsson, Folke, Homer-Dixon, Vredenburg and Loorbach2011; Olsen et al. Reference Olsson, Galaz and Boonstra2014). Furthermore, the importance of these factors can vary across cultures and biomes.

Recent work by international organizations focused on improving slum conditions and preventing their formation is reflected by a decrease from 39 percent to 30 percent of urban populations living in slums in developing countries between 2000 and 2014. Yet, absolute numbers of people living in slums continue to rise as a result of rapid urbanization and overall global population growth, as well as the failure of cities to provide appropriate housing and manage growth. Transforming slums into sustainable urban settlements requires a new understanding of slums as complex phenomena emerging from the interactions of multiple forces and the recognition of these emergent settlements not as “informal,” but as a “social production of habitat” – a definition intended to describe people producing their own habitat: dwellings, villages, neighborhoods, and even large parts of cities (Zárate 2016).

Box 2.1 The Complexity of Slums

Slum settlements are an example of a complex urban phenomenon with significant implications for the sustainability of an urban planet. Across the globe today, one in eight people (approximately 881 million) lives in slums, and this number is expected to increase in the near future (UN-Habitat 2016). According to the UN, the number of slum dwellers continues to increase, despite the decline in the proportion of the urban population residing in slums. Slums are a challenge to sustainable transitions for humanity: they increase poverty and demands on basic services in urban areas, threaten human health, and exert stresses on the environment. Spontaneous settlements typically occur in the most environmentally vulnerable areas, and their lack of proper sanitation and waste management systems are major sources of both environmental pollution and the spread of infectious diseases.

Among the various informal settlements associated with rapid urbanization, slums are a particularly challenging and urgent global phenomenon due to the perpetual poverty, deprivation, and sociospatial exclusion of slum dwellers, and due to their impacts on the overall prosperity of the cities in which they exist.

Both the emergent patterns of informal settlements and their evolution reflect the interaction of multiple factors and contrasting forces: population growth; rural-to-urban migration; weak governance; economic vulnerability and underpayment for labor; displacement caused by conflict, natural disasters and climate change; and, significantly, the lack of affordable housing options for the urban poor as governments increasingly disengage from a direct role in provision of housing. The complex interaction of these diverse factors often causes the housing sector to become susceptible to domination by speculative forces that tend to benefit affluent urban residents (UN-Habitat 2015).

For example, by comparing the current patterns of urban segregation to the traditional center-periphery pattern in Brazilian cities, Feitosa (Reference Feitosa2010) shows that complex interactions among bottom-up and top-down processes and mechanisms operate at multiple scales. A new pattern of segregation has resulted from the political and socioeconomic changes of the 1980s, superimposed on the typical center-periphery pattern that separates the wealthy from poor urban dwellers (do Rio Caldeira Reference do Rio Caldeira2000; Lago Reference Lago2000; Torres et al. Reference Torres, Marques, Ferreira and Bitar2002). The slowing of the Brazilian economy during the 1980s and a corresponding decline in per capita income led to an impoverishment of the population and an increase in social inequalities. The simultaneous establishment of the Federal Law for Urban Land Parceling (6766/79), which regulates the minimal requirements for development of urban settlements and was intended to improve access to infrastructure and public facilities of the periphery, promoted a larger social diversity in areas that were only occupied by the lower classes (do Rio Caldeira Reference do Rio Caldeira2000; Lago Reference Lago2000) while increasing the number of urban dwellers unable to afford the “legal city” or even to build their own dwellings in “irregular” settlements (Feitosa Reference Feitosa2010). Together, these factors prompted the emergence of favelas, the Brazilian slums found throughout various regions of the city, even in close proximity to wealthy neighborhoods (Torres et al. Reference Torres, Marques, Ferreira and Bitar2002).

What characterizes slums, from an urban complex dynamic perspective, is not location, but the living conditions experienced inside them. A slum, according to UN-Habitat, is a settlement in which the inhabitants suffer one or more of the following “household deprivations”: lack of access to an improved water source, lack of access to improved sanitation facilities, lack of sufficient living area, lack of housing durability, and lack of security of tenure (UN-Habitat 2011). The persistence of slums is the result of a reinforcing mechanism or positive feedback. Increased poverty and lack of basic infrastructure and services, together with a degraded and unhealthy environment, drive the emergence, persistence, and growth of slums both in developing and developed countries. Actions to improve slum living conditions require promoting policies and incentives that operate simultaneously on multiple levels, linking urban planning, financing, and legal and livelihood components from the bottom up. Transition to a sustainable future for urban slums implies acknowledgment of the self-organizing nature of such phenomena and the opportunities inherent in this self-organization for reorienting urban slums towards urban sustainability.

2.4 Complexity of Coupled Human-Natural Systems

Over the last three decades, complexity theory has provided a new basis for understanding how myriad local interactions among multiple agents can generate simple behavioral patterns and ordered structures. Cities are nonequilibrium systems; random events produce system shifts, discontinuities, and bifurcations (Krugman Reference Krugman1993, Reference Krugman1998; Batty Reference Batty2005), and patterns emerge from complex interactions that take place at the local scale, suggesting that urban development self-organizes (Batten Reference Batten2001). Emergent patterns are often scale-invariant and fractal, indicating that the emergent morphology of cities results from self-organizing processes operating at the local scale (Batty and Longley Reference Batty and Longley1994; Allen Reference Allen1997).

Understanding the complex relationships between patterns of urban development and the processes that maintain ecosystem function and resilience in urban areas requires a new framework to uncover the mechanisms that determine the relationship dynamics of urban ecosystem services and their roles in maintaining resilience of urbanizing regions (McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Andersson, Elmqvist and Frantzeskaki2015). Urban systems are hybrid ecosystems and several types of new hybrid functions may emerge from these interactions. For example, barrier islands in urbanizing estuaries are part of a tightly coupled system of human and ecosystem processes; they perform the hybrid function of protecting estuary biodiversity and controlling coastal flooding (Alberti Reference Alberti2016).

The rapid advancement of computer power, together with the remarkable emerging availability of high-resolution social and ecological data, provides unprecedented opportunities to reframe our questions (Figure 2.3). Insteadof asking how patterns of human settlements and activities affect social and ecosystem processes, we can ask: How do humans, interacting with their biophysical environment, generate emergent phenomena in urbanizing ecosystems, and how do these patterns selectively amplify or dampen human and ecological processes and functions? Cities are coupled human-natural systems in which people are dominant agents with a new capacity to redefine the rules of nature’s game (Alberti Reference Alberti2016). Although extensive urban research has focused on the dynamics of urban systems and their ecology, efforts to understand urban systems in an integrated manner are relatively recent and are only beginning to address the processes and variables that couple human and ecological functions (McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Pickett, Grimm, Niemelä, Alberti and Elmqvist2016a; Bai Reference Bai2016).

Figure 2.3 Examples of high-resolution tree species diversity (Street Tree Census, NYC), property values (Assessor data, NYC), and energy intensity (Energy consumption, NYC).

Scholars of both urban development and ecology have begun to recognize the importance of explicitly considering human and ecological processes in studying urban systems. Yet building an integrated approach to advancing such understanding challenges scholars from different disciplines to revise fundamental assumptions in their disciplines with regard to humans and ecosystems.

2.5 Insights for Urban Planning from Complexity Science

To navigate the transition towards a sustainable urban future, it is necessary that we understand cities as integrated social, economic, and physical systems in more precise and predictive ways. This requires quantitative models of the internal structures of cities and of the interactions between cities and the Earth’s natural environments that account for the processes of human development and economic growth, as well as their feedbacks on patterns of urban development. It also poses new challenges and offers insights for rethinking planning theory to more effectively contribute to urban governance in an era of global change (Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2012). Emerging socioecological innovations across world cities indicate possible pathways to set new trajectories for the future of our urban planet. By developing and analyzing qualitative scenarios combined with modeling grounded in new empirical analysis, we can begin to assess strategies and uncover transformational pathways for cities to transition to more desirable and sustainable futures (McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Iwaniec and Bai2017).

How can we plan in the face of complexity? What can we learn from complexity science that will help guide urban design and planning? An initial series of questions directs planners towards new perspectives on problem definitions: How do we define the problem? What are the boundaries of the system? What is the spatial scale of the analysis? What is the time horizon? What are the components (ecological, social, political, economic) within the system? What are the connections and feedbacks (physical, biogeochemical, biotic, social, economic, political)? What are the drivers? What is controllable? Where are the control points? What is known? What is ambiguous or uncertain? What might plausibly be changed? What information do we need to assess alternative problem solving strategies?

Complexity science provides new tools to conceptualize the city and urban regions as complex systems (Bettencourt 2013) and indicates key principles to guide their planning and management (Ahern Reference Ahern2013; Alberti Reference Alberti2016):

1. Diversity and modularity: Create and maintain diverse development patterns and modular infrastructure systems that support diverse human and ecosystem functions under different conditions and uncertain scenarios.

2. Self-organization: Focus on maintaining self-organization and increasing the capacity of coupled human-natural systems to adapt instead of aiming to control change and to reduce uncertainty.

3. Uncertainty: Expand the ability to consider uncertainty and surprise in urban decision-making by designing strategies and built infrastructure systems that are robust to the most divergent plausible futures.

4. Adaptation: Create options for learning through experimentation, and opportunities to adapt through flexible policies and strategies that mimic the diversity of environmental and human communities.

5. Transformation: Expand the institutional capacity for change through transformative learning by challenging assumptions and actively reconfiguring problem solving.

2.5.1 Conclusion

The increasing pressure from climate change (Rosenzweig et al. Reference Rosenzweig, Solecki, Hammer and Mehrotra2010), rapid urbanization (UN 2014), and the rapid development of infrastructure to prepare for these changes all pose new challenges to urban decision-makers to make important investment decisions while navigating complexity (McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Haase, Kabisch and Gren2016b). Tackling complexity and uncertainly in urban systems is challenging and will require new evidence, approaches, and tools. It will demand a new level of collaboration among ecologists, geographers, sociologists, political scientists, economists, planners, designers, and other disciplines to advance the field of urban ecology into a new urban science (McPhearson et al. Reference McPhearson, Pickett, Grimm, Niemelä, Alberti and Elmqvist2016a; Alberti Reference Alberti2017). To meet this demand, scholars will need to be able to identify examples of new practices that highlight opportunities for improving urban resilience and sustainability at the local and global scales (McHale et al. Reference McHale, Pickett, Barbosa, Bunn, Cadenasso and Childers2015).