Introduction

The global population is ageing (Rechel et al., Reference Rechel, Grundy, Robine, Cylus, Mackenbach, Knai and McKee2013; World Health Organization (WHO) 2015) and increasingly urban (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014), trends led by early industrialising countries like the United Kingdom (UK). In the UK, 24 per cent of the population is aged 60 and over, a proportion projected to rise to nearly 30 per cent by 2035, and over 80 per cent of the population lives in urban areas (Office for National Statistics, 2013; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2018). Similar patterns are evident in other high-income countries, including Denmark, the Netherlands and the Scandinavian countries, as well as the United States of America (USA), Canada, Japan, Australia and New Zealand (WHO, 2015; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016).

While the rapid growth of urban populations is a global trend, there are marked national differences in urban form, transport infrastructures and travel behaviour. For example, low-density development and limited public transport have contributed to car travel being a more dominant travel mode in US metropolitan areas than in the UK, where urban population densities are higher and public transport and active travel account for a larger proportion of trips (Giuliano, Reference Giuliano2004; Department for Transport, 2017b). Transport infrastructures and travel patterns also vary within countries, particularly between urban and rural areas (Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, White and Graham2014).

While the local environment and its transport system matter for everyone, they are particularly important for older people. A range of age-related factors lie behind their greater reliance on local amenities and social networks. Compared to younger adults, those aged 60+ are more likely to live alone (Dunnell, Reference Dunnell2008) and spend more time in and around the local neighbourhood (Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, Phillipson and Scharf2012; WHO, 2006). Because older people are less likely to drive and travel by car (Olanrewaju et al., Reference Olanrewaju, Kelly, Cowan, Brayne and Lafortune2016), they depend more heavily on the pedestrian and public transport infrastructure to access social networks and services.

In addition, while the majority of those aged over 60 are in good health, the prevalence of serious illness rises sharply with age (WHO, 2015), with conditions for which physical inactivity is a major risk factor – heart disease, stroke and cancer – driving this increase (Beach, Reference Beach2015). Levels of physical activity decline in later life (Bauman et al., Reference Bauman, Merom, Bull, Buchner and Fiatarone Singh2016); those over 60 are less likely to be physically active and to engage in active forms of travel like walking and cycling (Hutchinson et al., Reference Hutchinson, White and Graham2014). Nonetheless, walking remains an important part of daily life for older people. Evidence for England indicates that, along with housework, walking for travel and leisure is older people's major form of physical activity (Sport England, 2017). Not surprisingly, usual travel mode is a predictor of how much and how vigorously an older person walks. Compared to those making trips by car, those who walk, cycle and travel by bus take more steps and engage in more moderate/vigorous walking (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Fox, Hillsdon, Coulson, Sharp, Stathi and Thompson2011).

The importance of the local environment and its transport systems is increasingly recognised in policies for older people. The emphasis is on creating ‘age-friendly environments’ (Cottrell et al., Reference Cottrell, Gibson, Harris, Rai, Sobhan, Berry and Stanton2007) and ‘age-friendly cities’ (WHO, 2007; Buffel et al., Reference Buffel, Phillipson and Scharf2012) that support ‘healthy ageing’ (Oxley, Reference Oxley2009) and ‘active ageing’ (WHO, 2002). Realising such ambitions requires an appreciation of the needs and experiences of the local population, particularly those who depend most heavily on the local environment and its travel systems for their health and wellbeing (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2008). However, to date, evidence comes primarily from quantitative studies using definitions and measures in which subjective meanings can be lost (Day, Reference Day2008).

For example, the major source of UK evidence on personal travel, the National Travel Survey, defines personal travel as ‘the trips people make in order to reach a destination’ (Department for Transport, 2017a). Personal travel is therefore cast as an instrumental activity; a trip is ‘a course of travel with a single main purpose’ (Department for Transport, 2017a) such as going shopping or accessing services (e.g. medical consultations, entertainment, sports facilities). This understanding of travel frames much of the debate about transport exclusion and disadvantage (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Schwanen and Banister2017) and underpinned the introduction of the UK's concessionary bus scheme. By providing free bus travel for older people during off-peak times, the scheme seeks to provide ‘a lifeline to facilities both within and outside their local area’ (Department for Transport, 2012), particularly for those on low incomes (Butcher and Rutherford, Reference Butcher and Rutherford2015). The concessionary scheme operates via a swipe-card bus pass (in London called a Freedom Pass) which enables older people to travel without charge during permitted periods.

While defining travel in terms of its extrinsic value underlines its essential contribution to wellbeing, it can overlook and obscure the experience of travel for its own sake (i.e. not undertaken primarily or solely to reach a destination). The concept of ‘discretionary travel’ has been used to describe such travel (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite2017b); however, it is more widely used to describe journeys that, in contrast to work journeys and trips to access everyday necessities, are regarded as non-essential (e.g. visiting friends and family). As Parkhurst et al. (Reference Parkhurst, Galvin, Musselwhite, Phillips, Shergold, Todres, Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014: 129) note, by categorising such trips as discretionary, the concept ‘risks marginalising the travel aspirations and needs of older people’ for whom social visits – or simply being out and about – may be the main purpose of the trip.

Qualitative studies are uniquely equipped to uncover people's aspirations and experiences. They use methods and modes of analysis grounded in people's accounts of their everyday lives. Providing access to ‘experts by experience’ (NHS England, 2017), qualitative studies are increasingly valued by policy makers (WHO, 2016), with qualitative reviews and syntheses recognised to be an integral part of the evidence base for policy (Langlois et al., Reference Langlois, Tunçalp, Norris, Askew and Ghaffar2018).

There are a number of relevant reviews that include qualitative studies, including ones of walking, physical activity and healthy ageing (Annear et al., Reference Annear, Keeling, Wilkinson, Cushman, Gidlow and Hopkins2012; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Guell and Ogilvie2012; Moran et al., Reference Moran, Van Cauwenberg, Hercky-Linnewiel, Cerin, Deforche and Plaut2014; Dadpour et al., Reference Dadpour, Pakzad and Khankeh2016). However, none has a focus on older people's experiences of travel in the urban environment. Our review provides this focus. Mindful of national differences in urban form, transport infrastructures and travel patterns, our review focuses on the UK.

Aim

The aim of our review is to identify, assess and synthesise evidence from qualitative studies of older people's experiences of everyday travel in the urban environment in the UK.

Methods

Searching

We searched health, social science, and age- and transport-related databases for studies in English-language journals published between 1998 and 2017: MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus, Scopus and TRID (Transport Research International Documentation) and AgeINFO. Search terms included a combination of key words related to qualitative research methods, travel and the local environment. The searches were supplemented with hand searches of key journals (Journal of Planning Literature, Built Environment and the Journal of Transport and Health); we also checked references in earlier systematic reviews (Annear et al., Reference Annear, Keeling, Wilkinson, Cushman, Gidlow and Hopkins2012; Barnett et al., Reference Barnett, Guell and Ogilvie2012; Moran et al., Reference Moran, Van Cauwenberg, Hercky-Linnewiel, Cerin, Deforche and Plaut2014; Dadpour et al., Reference Dadpour, Pakzad and Khankeh2016). Additionally, we asked leading researchers in the fields of older people and transport to check the identified studies for completeness.

Screening

Records were screened by title and abstract to identify UK studies published in peer-reviewed journals. The full texts of journal papers were retrieved and screened by two reviewers (KF and HG) to determine eligibility for inclusion. Any discrepancies were discussed and agreed by consensus.

Eligible studies (a) included people aged ⩾60 resident in urban/suburban areas of the UK and (b) used a qualitative research design to gather older people's experiences of everyday travel in the urban environment. We included mixed-method studies where the qualitative component was reported separately, baseline data from intervention studies, and studies including both older people and stakeholders if the experiences of older people were separately reported.

We excluded studies where (a) participants were recruited based on their health condition (e.g. studies of people with diabetes); (b) the experiences of older people were not separately reported (e.g. studies of adults); and (c) rural participants were included and the experiences of older people in urban/suburban areas were not separately reported. We contacted study authors where the residential location of participants was unclear.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Data extraction was undertaken by one reviewer (SdB) and checked by another (HG) using a standardised form covering aims, study details, study design, analytical methods and key results. We assessed the quality of the reporting of the study using a standard framework which covers a range of domains, including methods, data analysis and ethics, with a maximum possible score of 36 (Hawker et al., Reference Hawker, Payne, Kerr, Hardey and Powell2002). Appraisal was undertaken by one reviewer (SdB) and checked by another (KF). The domains were not weighted and there was no a priori quality threshold for excluding papers; assessment was undertaken to ensure transparency (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Booth and Lloyd-Jones2012; Noyes et al., Reference Noyes, Booth, Flemming, Garside, Harden, Lewin, Pantoja, Hannes, Cargo and Thomas2018).

Synthesis

We used thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008), an approach that mirrors thematic analysis used in primary studies. The main difference is that the data include authors’ interpretations as well as participants’ accounts.

Thematic synthesis is a three-stage process that moves iteratively between coding, to the identification of descriptive themes, to the generation of cross-cutting analytical themes (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008; Booth et al., Reference Booth, Noyes, Kate, Gerhaudus, Wahlster, Van der Wilt, Mozygemba, Refolo, Sacchini, Tummers and Rehfuess2016). The first stage involved line-by-line coding of participant accounts and author interpretations by one reviewer (SdB) using NVivo version 11 (QSR, 2012). Coding was inductive, with the set of codes expanded as additional studies were added (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008). At least one code was given to all statements relating to travel and/or the local environment; statements often had multiple codes. The preliminary codes were discussed and refined by the review team (SdB, KF, HG). The final set comprised 151 codes, all of which related to older people's views and experiences; example codes included ‘bus travel gives a sense of belonging to society’ and ‘unwilling to rely on social network for help’.

For the second stage, groups of related codes were identified, and combined into broader descriptive themes by the review team (SdB, KF, HG). The process involved repeated reference back to the papers from which they were derived, to ensure coherence and their grounding in the views and experiences of study participants. The descriptive themes related to older people's experiences of different travel modes (e.g. bus, car) and their local environment, as well as to individual-level factors (self-identity, health and personal circumstances, in particular).

The third stage of our synthesis involved identifying and mapping links between the descriptive themes (travel modes, local environment, individual-level factors) to generate analytical themes that, together, made sense of older people's experiences of everyday travel. Themes were discussed and refined with the project's policy advisers. The group included senior local government and National Health Service staff tasked with developing and/or delivering health, transport and environmental policies and services in their local urban areas, together with the lead for transport and health for older people at a major UK charity.

The review was guided by the ENTREQ (‘Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research’) statement (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver and Craig2012).

Results

General study characteristics

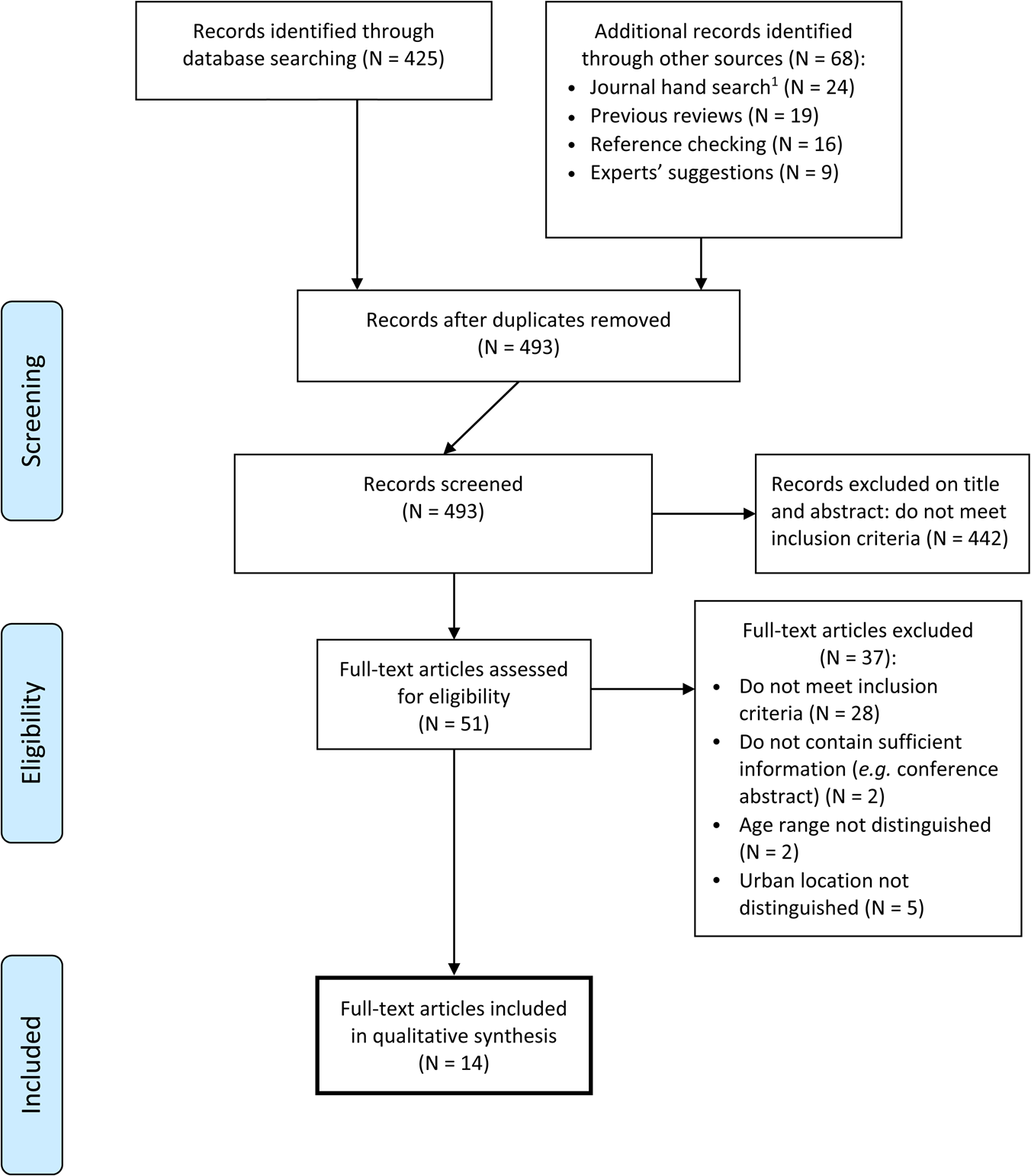

We identified 493 records. After screening (see Figure 1), 14 papers (reporting on 12 empirical studies) met the review inclusion criteria. Table 1 summarises the papers, including their aim/research question, participant details, sample size, location, methods and quality score. The majority (11) were published since 2010. Quality scores ranged from 20 to 30; only three papers had scores below the mean score of 25. Lower-scoring papers provided less information on ethics and methods (e.g. data collection, sampling strategy, data analysis and bias). Papers were based on studies undertaken in major cities and other urban areas in England, Scotland and Wales; there were no studies in Northern Ireland. Three included both urban and rural settings but enabled identification of findings relating to urban participants.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart of search strategy and study selection.

Table 1. Summary of included studies

Notes: N = 14. 1. Papers arising from the same study. 2. Papers arising from the same study. 3. Location provided by author. 4. ‘Black Country’ refers to the metropolitan area around Birmingham, characterised by coal-based industries in 19th-century Britain. ADL: activity of daily living. BME: black and minority ethnic. GCSE: General Certificate of Secondary Education. GPS: global positioning system. IMD: index of multiple deprivation. NDC: New Deal for Communities. QA: quality appraisal. QGIS: qualitative geographical information systems. UK: United Kingdom.

Some papers (hereafter referred to as studies) were concerned with older people's travel experiences (Hammond and Musselwhite, Reference Hammond and Musselwhite2013; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Goodman, Roberts, Steinbach and Green2013; Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014; de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016; Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite2017b). Others explored their experiences of being out and about in their local environment (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Mathers, Laburn-Peart, Orford and Dalton2007; Day, Reference Day2008, Reference Day2010; Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015). A third group were concerned with active ageing and independence (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Guell et al., Reference Guell, Shefer, Griffin and Ogilvie2016). The majority (N = 9) asked participants about their health status (e.g. self-reported health, quality of life, physical mobility).

The studies included participants with a broad range of levels of mobility. Two (Guell et al., Reference Guell, Shefer, Griffin and Ogilvie2016; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016) noted that participants with mobility limitations (e.g. not able to walk) were excluded and two noted that participants in sheltered accommodation and residential care homes were included. While not directly stated in the majority of studies, it is clear that the majority of participants were living in their own homes.

Semi-structured interviews were the predominant data collection method; focus groups, walk-throughs and participant observation were also used. Prompts were used to aid data collection, including photographs taken by participants (one study) and separately collected participant accelerometry data (two studies). Most studies (N = 11) used one method of data collection; three used two methods.

Together, the studies reported the experiences of over 340 older people, with sample sizes ranging from five to 60. All participants were aged 60 and over. In eight of the studies, participants were aged 65 and over; in five of these, participants were aged 70 and over (see Table 1). Participants lived in advantaged and disadvantaged communities in inner-city, urban and suburban areas in England, Scotland and Wales. Limited information was provided on co-habitation status (five studies); in these studies, approximately half the participants lived with a partner. Limited information was also given on ethnic background (six studies); in these studies, it was clear that the majority of participants were White.

Analytical themes

Four inter-connected themes were identified. Each theme pointed to the intrinsic value of travel, a value particularly evident in the first two themes.

The first two themes related to ‘getting out’ and being an independent traveller. Together, the themes made clear that travelling in the local environment was not simply a means to an end. The process of travel had its own meaning. It was an act and an experience from which older people derived enjoyment; participants therefore often referred to its contribution to their wellbeing. The third and fourth themes highlighted the ways in which environmental and transport-related factors mediated older people's travel experiences – and therefore determined the extent to which the intrinsic as well as the extrinsic value of travel could be realised. Studies focused on older people's experiences of their local environment and local travel systems, respectively, contributed most to these themes.

The four themes were discussed with the project's policy advisers who offered insights and refinements. While confirming the salience of the themes, suggestions were made about strengthening the underlying message of our review about the value that older people attach to the process of local travel: namely its potential to be identity-affirming and a space for social interaction and community engagement. The section below takes account of this feedback. The four themes are discussed in turn, with their interconnections illustrated in participant accounts. In line with our focus on older people's experiences, these are given priority in the presentation of our findings.

Analytical themes

The importance of getting out

The study participants made clear that travelling in the local environment was not simply about reaching destinations. Travelling was also an end in itself.

The intrinsic benefits of local travel had multiple and inter-related dimensions. Firstly, the act of ‘getting out’ was a way of countering the isolation of the home; as Sixsmith and Sixsmith (Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008: 288) observe, the home can be ‘a place of intense loneliness’:

It's the easiest thing in the world just sitting there, just read or do something. You've got to get out; you've got to move about. (Guell et al., Reference Guell, Shefer, Griffin and Ogilvie2016)

I could easily sit here all day … you know, especially if the weather is bad and you can't get out … but it's no good you've got to make an effort … I make myself go out to a certain extent … I hate every minute I live on my own. (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008)

Having a walking companion could encourage and enhance the enjoyment of getting out, while a partner with limited mobility could constrain travel options (Day, Reference Day2008, Reference Day2010; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015; Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015, Guell et al., Reference Guell, Shefer, Griffin and Ogilvie2016):

We used to go there (the supermarket) more frequently, but now she can't walk much, we don't walk down, we take the car down. I know it's stupid for about 400 yards. (Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012)

Secondly, getting out offered opportunities to ‘see life’ and feel socially connected. Across all the studies and across all travel modes, older people spoke about these personal benefits. These benefits were particularly evident for travel modes supported by public funds. For example, with respect to walking, the following accounts were typical:

I don't like sitting … and just watching telly or, I've got to be on the go. So … I do like every day, at least, to get out in the fresh air, have a little walk, even if it's only for an hour, just down the city, you know, or anything. (Guell et al., Reference Guell, Shefer, Griffin and Ogilvie2016)

So you walk down the street … ‘good morning, lovely day, how are you keeping, you've got a stick, what happened?’ that kind of thing. And people talk to you. (Day, Reference Day2008)

Participants described the benefits of travelling by bus and using community transport in similar ways:

I get out every day because I get bored living alone in the flat, so I get out every day, catch the bus, sometimes two, three buses a day. (Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014)

Getting out and about [using community transport] you still see things. You see life going on around you. You don't experience or feel that at home. (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a)

Being disabled … and more or less housebound the community transport enables me not only to be able to get my weekly shopping but to meet other people. (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a)

Being an independent traveller

The second theme relates to the importance of remaining independent, despite mobility limitations and financial constraints. Older people value travel systems and environments that support, and do not compromise, their strong preference for independence. Two inter-connected dimensions were evident: decisional autonomy and self-reliance.

The importance of being free to make travel decisions – what Schwanen et al. (Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012: 1317) describe as ‘freedom to’, was evident across the studies (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014; Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a). Everyday travel, whether by foot, car or bus, provided a way of enacting one's ‘freedom to’; independent out-of-home mobility was therefore highly valued. This was captured in the comments of one study participant:

If I never had my bus pass, I wouldn't have the freedom that I've got. I go to clubs … Which helps me to, you know, do the rest of the week, so it's not so long. (Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014)

The car was particularly valued as offering a latent capacity for mobility, what Musselwhite (Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a: 55) refers to as ‘potential for travel’:

That's what the car does you see. Takes you where you don't need to go, you see. And for me that's life. (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a)

I don't feel I have the freedom that I do with the community transport as I did with a car. I am taken places. It's nice but I miss the freedom to choose, the journey, how long we stay and so on. (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a)

Intertwined with freedom to make travel decisions was being self-reliant and, specifically, not being dependent on family and friends to meet one's travel needs. The desire to remain self-reliant for as long as possible was a constant refrain. Driving a car, taking the bus, walking with mobility aids, using community transport and, for those who could afford it, taking taxis were all seen as preferable to depending on family and friends:

I couldn't have a better family but I still don't want to be dependent and don't want to be a nuisance to anybody. (Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012)

[By using community transport] I'm not a burden to them. They're busy, they wouldn't be able to take me about you see. (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a)

I don't like keep asking ‘can I go there?’ while I can manage it, and that's why I bought my two-wheeler [rollator]. (Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012)

As the accounts above indicate, travel represented an important arena in which to exercise agency. Together, being able to make everyday travel decisions and be self-reliant in enacting them demonstrated independence and helped to avoid the connotations of dependency associated with being old (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012, Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014; Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite2017b). Being an independent traveller signified and enacted a broader capacity for independence in old age as the accounts below illustrate:

I appreciate the fact that I can get out and about and I can do things for myself, it helps me to remain independent. And I can go out and do my shopping, get my paper, travel. If I travel I, you know, I could do it if I need. (Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012)

The car is a symbol of my freedom and my ability still to be in control. (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a)

I desperately wanted to … go into the recreation ground, because that had been our stamping ground when we were young … And the day I did that, I came back and … I felt marvellous! And I was going … round streets … and looking at people's gardens and, yeah, … I felt taken out of myself! (Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012)

The importance of the local environment

The first two themes point to the intrinsic value of local travel for older people. Its instrumental value was also emphasised: travel provided access to local facilities and social networks. Travelling to a destination – the official definition of personal travel – was also a spur to getting out, giving structure and focus to the trip and enhancing its opportunities for social interaction. Across the studies, participants spoke about how the availability of local amenities and, in particular, food stores, newsagents and post offices, influenced their motivation to, and experience of, travel (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Mathers, Laburn-Peart, Orford and Dalton2007; Day, Reference Day2008, Reference Day2010; Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012, Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015; Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015). Thus, living close to amenities facilitated getting out (de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015) and ‘street socialising’ (Day, Reference Day2008: 308). As two participants in the study by Stathi et al. (Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012) observed:

You got a hardware shop, and you got bakers, greengrocers shop, hairdressers, you got dentist, you got a library, so there's lots of, there's fish and chip shops, a lot of take-away shops all up there. It's all in one; you could go up there and get everything what you wanted, really.

Whenever you go to up the top [of the high street] there's always somebody stopping, you have a few words and chat and things.

A more common experience, particularly among older people in disadvantaged areas, was the loss of these local centres, and the consequent need to travel beyond the local area to access the services they needed. As Milton et al. (Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015) note, older people lamented the loss of local amenities, particularly those seen to be the ‘hub’ of the community.

There's nothing in this area … not even a swing for a child … nothing for old or young. (Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015)

[In the past] each area had all these shops, you could buy here and there, and cross the road and get so many things on the other side. It was lovely, it was an outing … Everybody used the local shops and you met people practically every other day. You could meet and stand and blether to people for as long as you liked. But that's what I am saying, the companionship – that's gone now I think. (Day, Reference Day2008)

In addition to local amenities, the studies point to a range of environmental features that impacted on older people's experiences of travel. Many of these features are captured by what Zandieh et al. (Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016: 2) refer to as ‘the micro built environment’, a concept that includes pedestrian infrastructure, aesthetic appearance and personal safety.

The pedestrian infrastructure includes streetscape design, with study participants describing the importance of benches, toilets and bus shelters for enabling walking and bus travel as well as facilitating social interaction (Day, Reference Day2008, Reference Day2010; Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Guell et al., Reference Guell, Shefer, Griffin and Ogilvie2016; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016).

The infrastructure for walking also included traffic conditions and pavement quality, where pavement width, surfaces and road crossing points were particularly highlighted:

And the high kerbs, so if we are going to a certain place we have got to say ‘now we have got to go along there and there's a low kerb there, and go down here, but I have got to cross there and move along there’. You can't just go from A to B. (Day, Reference Day2008)

I used to go across the road. But I stopped going there because again, if I was crossing the road, I could fall down. I don't need anything to fall over, I just fall down. And you know … a driver, who couldn't stop in time to stop running over you. And I've got no intention of being run over. (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008)

I confess I do go outside my house, but only in the quiet times. I look very carefully [for crossing the roads[. I can say I stop halfway, on the white lines you see in the middle of the road. (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016)

The studies included examples of where travel was impeded by uneven pavements with broken bottles and pavement obstructions, e.g. cars parked across the pavement area. As one participant put it:

When we walk up here, we have to be very careful! Broken bottles and broken pavements! … Broken pavements and slope! It would definitely mean you have to watch. (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016)

Aesthetics refers to ‘a sense of beauty and visual appearance of a neighbourhood’ (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016: 2), e.g. natural features and enjoyable places to walk. As a participant in Day's study noted:

I would imagine everybody wants to look at a thing of beauty. It kind of lifts your spirits. (Day, Reference Day2008)

Studies included descriptions of how the natural environment, even in a miniaturised form of flower tubs in the shopping centre, enhanced the aesthetic enjoyment of the local environment and engendered a sense of civic pride (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Mathers, Laburn-Peart, Orford and Dalton2007; Day, Reference Day2008; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016). Along with architecturally varied buildings, study participants noted how flower beds and trees as part of the streetscape and well-maintained front gardens with flowers encouraged walking and increased the enjoyment of doing so (Day, Reference Day2008, Reference Day2010; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Fox, Hillsdon, Coulson, Sharp, Stathi and Thompson2011; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016):

I think it [nice flowers and gardens] brings you back to nature and makes you realise there is more to life. Even just sitting watching flowers, looking at the flowers, the different colours, the different shape of the petals and all that, you could spend ages. (Day, Reference Day2008)

It (my neighbourhood) is boring. These little industries are around. There is not many pretty gardens and places to look up regularly. You can see all industries over there! (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016)

There's plenty of greenery around here and it's quite nice to take a walk up ’round. (Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012)

Other aspects of the local environment, like air quality and quietness (Day, Reference Day2008, Reference Day2010; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Hammond and Musselwhite, Reference Hammond and Musselwhite2013; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016), were also described in terms of their impact on older people's enjoyment of travel.

I like peace and quiet. I like, I mean you can hear yourself. (Day, Reference Day2008)

I like fresh air and exercise. This area has a good air quality because of the [few] cars. (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016)

Accessing and enjoying the local environment were also affected by changes in the weather and across seasons (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015; Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016). As Milton et al. (Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015) note, there is a seasonal variation in older people's travel environment; in winter, their neighbourhood reduces in size. Cold and wet days were avoided, particularly if adverse weather conditions made pavement surfaces slippery:

I mean I don't like going out when it is icy or snowy because I wouldn't want to fall down or anything like that. (Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012)

We wouldn't go [walking] if it was raining! (de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015)

Older people's concern for their personal safety was discussed in the majority of studies (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Mathers, Laburn-Peart, Orford and Dalton2007; Day, Reference Day2008, Reference Day2010; Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Green et al. Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014; de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016). As Parry et al. (Reference Parry, Mathers, Laburn-Peart, Orford and Dalton2007: 126) note, ‘fear provides a key nodal point in residents’ accounts’, particularly for women (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016). The studies described how fear was environmentally determined, with particular times of the day (after dark and at night) and settings (e.g. being in proximity to groups of young men) perceived as particularly unsafe. Older people ‘segregated themselves in time’ (Day, Reference Day2010: 2667), going out in the morning and avoiding night-time to reduce the risk of being in situations perceived to be potentially threatening:

I wouldn't walk down there at night. No way. Well I wouldn't even get out the car, ’cause the pub on the corner it's always got plenty of people round it you know. (de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015)

Gangs hang around outside and you walk around not without their prejudice. You are not one of them … they won't let you to pass through! They will come right up to you when you want to move! (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016)

I've been into town, and I've come up the road and I mean there were five young fellas coming down the road, and I thought to myself: ‘Do I have eye contact?’ cos I like to, I like to have eye contact with people, you know, and I thought: ‘No, just keep your head down’. (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Mathers, Laburn-Peart, Orford and Dalton2007)

I don't like going through the passageway [a narrow street between buildings] on my own … I'm not very keen on going through there because there's like high fencing, and there's nobody about, and well … I mean, it's not a walk for a really elderly person to do on their own. (Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012)

A consistent finding across the studies was the area-based inequalities in the micro built environment. Older people in disadvantaged areas were more likely to perceive their local environment as having a poor pedestrian infrastructure, lacking beauty and being unsafe.

Participants in disadvantaged areas spoke about the lack of benches and toilets, with those available vandalised and no longer usable (Day, Reference Day2008; Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016). They spoke about rubbish on the streets and in alleyways, with bins overflowing, rubbish bags on the street and litter outside take-away food outlets (Day, Reference Day2008; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016). They described traffic density, traffic pollution and roads that were difficult to cross (Day, Reference Day2008; Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012; Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016), and their accounts pointed to heightened concerns about their personal safety. For example, Zandieh et al. (Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016: 13) noted how participants in the high-deprivation areas in their study described their fears about ‘gangs and groups of hooligans dominating pavements and their anti-social behaviour as well as high crime rate, drug use and lack of street lights’. In contrast, a resident in a low-deprivation area observed:

There is nothing to frighten anyone, there is no real crime on this area. You know, no vandals around the streets. So, no frightening people. (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016)

Given these very different environments, older people in disadvantaged areas were more likely to limit walking to instrumental journeys and have fewer opportunities to experience the intrinsic benefits of getting out; as Day (Reference Day2008: 307) observed, ‘few actively enjoyed the environment’.

The importance of local transport systems

It was not only the quality of the local environment that determined the benefits that could be derived from everyday travel. They were determined, too, by the local transport system.

Firstly, older people discussed the provision of local travel facilities. As one study participant put it:

Transport is a very important factor in terms of my life – or lack of transport. (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008)

The availability, accessibility, connectivity and comfort of travel modes were all discussed. For example, as the accounts below indicate, walking was facilitated by the availability and accessibility of traffic-free routes – and by a local bus service that enabled older people to combine travel modes:

Yesterday we walked down [to the seafront] from here and took a rest and then finished up going almost to [X]. Coming back, catching the bus and coming home. (Day, Reference Day2008)

We used to catch a bus and go up on the bus and have a little walk, have an ice cream, have a rest, and come back. But you can't do that now because we've got no buses. (Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015)

While the intrinsic benefits of car travel (see the first and second themes) were discussed, having a car was also often explained in terms of the lack of suitable alternative travel modes.

Of course buses stop at 6 o'clock so you need a car if you want to get out in an emergency or anything like that, or go out to the theatre. (Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012)

Quite frankly I don't know how we'd manage if we didn't have the car. (Zandieh et al., Reference Zandieh, Martinez, Flacke, Jones and van Maarseveen2016)

You don't need a car but it's surely handy to have one. Because you've got a 10-minute walk down to the bus … and the buses are not terribly reliable as you probably read in the paper. (Stathi et al., Reference Stathi, Gilbert, Fox, Coulson, Davis and Thompson2012)

Travel-focused studies noted how the cost of a travel mode was integral to older people's assessment of its availability. While taxis offered a quick door-to-door service, they were expensive and were therefore not regarded as a mode of everyday travel (Sixsmith and Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith and Sixsmith2008; Schwanen et al., Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012). Conversely, the free bus pass scheme facilitated everyday travel, as the following accounts illustrate:

That is one good thing about living here, an excellent bus service … and, costs me nothing. I would say probably four times, four days a week. (de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Stathi and Fox2015)

Well, I use it every day … And if I didn't have a Freedom Pass, I wouldn't be able to go out every day. Because I've got sticks, so I can't walk very far. (Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014)

It's a godsend, because, it's very lonely where I am, although it's sheltered housing, and you've got your flat, and you'd be lost without it. It's the only thing I have that gets you around. (Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014)

It was not only the physical and financial aspects of different travel modes that mattered for older people. The studies pointed to the importance of the social worlds of travel. As the accounts below indicate, walking, taking the bus and using community transport enabled them to enter and be part of this wider public sphere:

[Walking the dog] it's marvellous for meeting people … they'll wave as they know it's my time. So I have made quite a few friends just through the dog. (Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015)

Everybody was saying, oh gosh we don't often see you on the bus! Because it's quite a social occasion for a lot of these ladies … because they all meet up, you know, if they're on their own and they don't see many people, it's quite nice. (Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015)

You want something to help your life along. I find that people do speak to you on the bus. (Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014)

It's a weekly catch up with friends basically! I really look forward to a good chinwag on the [community transport] bus. (Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a)

Strengths and limitations

Our review drew on the experiences of over 300 older people living in the UK's urban areas. Health, social science and transport databases were searched, providing access to relevant research across a broad range of research fields and disciplines.

The breadth of studies included in the review enabled us to highlight the multi-layered connections between wellbeing, travel and the local environment. However, the focus on the urban environment means that older people living in rural areas were excluded. A separate review of these studies is in progress. The breadth of the studies also means that the review does not provide in-depth analysis of all dimensions of older people's experiences of everyday urban travel. To give two examples, the experience of driving cessation and of fear for one's personal safety are noted but not discussed in detail; this more detailed treatment is provided in bespoke reviews (e.g. Lorenc et al., Reference Lorenc, Petticrew, Whitehead, Neary, Clayton, Wright, Thomson, Cummins, Sowden and Renton2013, Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a).

Two sets of papers are drawn from the same studies (Day, Reference Day2008 and Reference Day2010; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Goodman, Roberts, Steinbach and Green2013 and Green et al., Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014). As a check, we examined their contribution to the themes (Noyes et al., 2018). This confirmed that the papers focused on different dimensions of the experience of everyday travel in the local environment and made a separated contribution to the thematic synthesis.

Few studies (N = 5) provided information on the household circumstances of participants; these studies note that around half were not living with a partner (see Table 1). UK data point to marked gender differences in the domestic circumstances of men and women, with women aged 65 and over much more likely to be living alone than men in this age group. By age 85, less than one in ten women are living with a spouse or partner, compared with over a third of men (Dunnell, Reference Dunnell2008). As this suggests, there is an important gender dimension to the experience of the home as a lonely place and to the value that older people attach to getting out and about in their local environment. Our review could not explore this dimension but it would warrant further study.

The perspectives of frailer older people are likely to be under-represented in our review. Studies recruiting participants on the basis of their health condition were excluded and only two of the included studies noted that some participants were living in care settings. Care home residents are a group highlighted by our policy advisers as facing particular difficulties around everyday travel, and therefore with accessing basic services and social networks (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Blom, Cox and Lessof2006). We recommend that a future review should focus on the travel needs and experiences of older people in care homes, to complement and add depth to qualitative reviews of their broader experiences (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Yu and Kwong2009; Bradshaw et al., Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012).

The studies were located in both more- and less-disadvantaged areas of urban Britain, and the majority included information on the area deprivation profile and/or gave details of the socio-economic circumstances of the participants (Table 1). Our synthesis pointed to marked social inequalities in older people's everyday travel experiences. Everyday travel for more disadvantaged groups depended on walking and bus travel, with the latter made possible by the concessionary bus scheme and by an accessible and frequent bus service. Social disadvantage was also structured into the localities in which they lived; these localities were characterised by micro built environments that were less easy and enjoyable to walk in. Compared to those living in more advantaged areas, older people in poor urban environments described a pedestrian infrastructure that was more hazard-strewn and harder to navigate, particularly for those with mobility needs. They spoke, too, of a physical environment that engendered less sensory enjoyment and civic pride, and a social environment more likely to generate anxieties about personal safety. As this suggests, there are powerful environmental determinants of active travel (Owen et al., Reference Owen, Humpel, Leslie, Bauman and Sallis2004).

While the impact of social disadvantage is discussed, the studies shed less light on how ethnic and cultural background shapes older people's experience of travelling in the urban environment. Six studies provide information on ethnic background, noting that all or the majority of the participants were White British. However, no studies reported the ethnic background of participants whose accounts are quoted in the studies and only two referred to culturally important venues, like places of worship and traditional food outlets (Green et al. Reference Green, Jones and Roberts2014; Milton et al., Reference Milton, Pliakas, Hawkesworth, Nanchahal, Grundy, Amuzu, Casas and Lock2015).

The limited information on ethnic background suggests that our review captures the experiences of local travel for the UK's majority ethnic group. The themes and findings that emerged – the intrinsic benefits derived from ‘getting out’ and feeling part of the wider community, being fearful about travelling at times and to places where one feels at risk – may be experienced differently by older people from minority groups, particularly in areas scarred by ethnic tensions. With the ageing of the UK's minority groups (Lievesley, Reference Lievesley2010), qualitative studies that capture ethnic and cultural diversity in older people's experiences of travelling in their local environment are urgently needed.

The thematic synthesis was shared and refined in discussion with policy advisers working at local, metropolitan and national level. They confirmed the salience of the four themes and made two broad sets of observations.

Firstly, those directly engaged in supporting the wellbeing of their population (e.g. in primary care and through cross-agency wellbeing plans) emphasised the importance of our findings around the value that older people attach to the process of travel: to being ‘out and about’ in their locality. This key finding was seen as particularly relevant at a time of reductions in local government funding and the increasing emphasis on locally driven strategies to improve wellbeing. As this group of advisers noted, our review highlights how older people are motivated by both the intrinsic value (getting out) and extrinsic value (getting there) that travel in the local environment offers them. They noted the potential contribution that enhancing the enjoyment of local travel could make to improving quality of life in older age and, more broadly, to promoting community cohesion. The feedback from our advisers suggested that older people were an instructive case study for local policy making and service delivery. From the older people's experiences, general principles could be derived to enable policy makers and planners to meet the travel needs of the whole population better.

Secondly, the project advisers noted that the themes may relate more strongly to the experience of older people without mobility needs than to frailer older people and those in care homes, an observation consistent with the selection criteria for the review and the participant profile of the individual studies within it (discussed above).

Discussion

In both research and policy, local travel is seen primarily in terms of the destinations that it enables people to reach. It is an instrumental activity undertaken to access other sites: the shops, the doctor's surgery, leisure facilities, and the homes of family and friends.

The extrinsic value of local travel and transport systems for older people came out clearly in our synthesis. In some studies, participants lived close to local amenities and spoke about how having these facilities in one place meant their everyday travel needs could be easily met. A more common experience was of losing the local services on which they had previously relied. For both groups, local travel facilities were key, including their availability (including in the evening and at weekends), connectivity (e.g. walkways that connected with local buses) and cost. For those on low incomes, it was clear that, in line with quantitative evidence (Mackett, Reference Mackett2015), the concessionary bus scheme promoted accessibility to facilities. Our findings therefore lend weight to policies that seek to improve and equalise access to transport, e.g. by investing in the pedestrian infrastructure and in concessionary bus fares for older people.

Our analysis also supports a broader perspective. It suggests that everyday travel is about more than moving from place to place, and transport is more than the means by which this movement takes place. As Ziegler and Schwanen (Reference Ziegler and Schwanen2011) and Parkhurst et al. (Reference Parkhurst, Galvin, Musselwhite, Phillips, Shergold, Todres, Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014) note, reaching destinations captures only one aspect of the process and experience of mobility. Classifying travel by trip purpose and destination can obscure these broader meanings, including ‘the importance of engagement with the familiar locale’ (Parkhurst et al., Reference Parkhurst, Galvin, Musselwhite, Phillips, Shergold, Todres, Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014: 128). In a similar vein, Musselwhite (Reference Musselwhite and Musselwhite2017a, Reference Musselwhite2017b) argues that travel serves a ‘hierarchy’ of mobility needs, from primary (practical) needs, through secondary (social and affective) needs to tertiary (aesthetic) needs. A single journey can therefore meet multiple needs.

It is this broader understanding of everyday mobility that our synthesis brings out. It points to the importance of travel for its own sake, and the wellbeing benefits that older people experience from the act and process of travelling in their local environment. These benefits are evident in all four themes. Under the first theme, older people spoke of ‘getting out’ as a way of counteracting the loneliness and tedium of home life and enabling them to feel part of a wider social world. Under the second theme, older people described the meaning of personal travel, stressing the value they attached to making autonomous travel decisions and being self-reliant in enacting them. All modes of transport – cars, public transport, community transport, and walking with or without mobility aids – were described in these terms. They were valued because they enabled older people to be independent and to demonstrate this capability to others, particularly to family members.

The third theme turned the spotlight on how the contexts of everyday travel mediated its potential benefits. The pleasure of getting out and the opportunity to be independent depended on the quality of the local environment and its travel systems. Thus, with respect to the local environment, study participants noted that they depended on physical features and amenities (including benches, toilets, wide pavements, safe crossing points), along with their state of oversight and repair (e.g. vandalised benches, uneven pavements, broken bottles). Fear compromised the enjoyment of travel and limited travel opportunities, with older people avoiding times and places where they felt unsafe. Aesthetic appearance was integral to the psycho-social benefits of everyday travel, with participants noting the pleasure they derived from an area's architecture, quietness, air quality and natural features. The importance of aesthetic appearance is well recognised with respect to urban parks and green spaces. As a review of qualitative studies of urban parks notes, ‘natural’ features like colourful displays of flowers, well-tended gardens and a sense of fresh air are among the attributes that people value (McCormack et al., Reference McCormack, Rock, Toohey and Hignell2010). Our review suggests that these attributes also matter for everyday travel, with aesthetic features both motivating local travel and increasing its enjoyment.

The intrinsic benefits of travel come out again in the fourth theme. Local travel systems, and the travel modes that they sustain, are obviously a prerequisite for travel. But our review makes clear that they are valued not only to reach destinations; older people value the social connections that travel modes make possible. The accounts of older people suggest that, when they travel as pedestrians, bus travellers and users of community transport, they become part of communities that make a vital contribution to their wellbeing. In consequence, their everyday travel may be experienced as more enriching and health-enhancing than the activities at its destination, a feature also noted about journeys to holiday and tourist destinations (Parkhurst et al., Reference Parkhurst, Galvin, Musselwhite, Phillips, Shergold, Todres, Hennessy, Means and Burholt2014).

Among the different travel modes, walking and bus travel stood out for their potential to enable older people to reach destinations and to meet important psycho-social needs. Travelling by foot and by bus, supported by the national bus pass scheme, are both free. Singly and together, they can enable older people to get out – and to enjoy being independent, self-reliant travellers and part of the wider community. Investment in the pedestrian and public transport infrastructure can also support active travel and reduce the environmental costs of road transport, by reducing fossil fuel emissions, noise pollution and traffic accidents (Woodcock et al., Reference Woodcock, Edwards, Tonne, Armstrong, Ashiru, Banister, Beevers, Chalabi, Chowdhury and Cohen2009; Hickman and Banister, Reference Hickman and Banister2014). These benefits bring further dividends for both older people and wider society.

In conclusion, our review of older people's experiences makes clear that the enjoyment of travel as well as its functionality matters. Both provide principles to guide policy development and decision-making. As our policy advisers suggested, existing travel systems and future investments could be assessed not only in terms of whether they enable people to reach destinations – but whether, additionally, they maximise the opportunities for people to enjoy and derive benefits from being ‘out and about’ in their local community.

Acknowledgements

We thank three external research experts, Judith Green, Barbara Hanratty and Charles Musselwhite, for help with identifying papers that our searches may have missed. We also thank Hugh Ortega Breton for his contribution to the initial scoping work to inform the focus of the review. Particular thanks go to the project's policy advisers for their very helpful advice on the initial set of themes. We received feedback from transport planning, health and voluntary leads at Calderdale Council, co-ordinated by Paul Butcher (Director of Public Health, Calderdale Council). Co-ordinated by Nick Grayson (Climate Change and Sustainability Manager, Birmingham City Council), we received feedback from Karen Creavin (Chief Executive of Birmingham's Active Wellbeing Society, a community benefit society) and Ewan Hamnett (Lordswood House Group Medical Practice, Birmingham). We also received feedback from Joe Oldman (Housing and Transport Policy Manager, AgeUK). The review was undertaken as part of the Public Health Research Consortium (PHRC), funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Health. Information about the wider programme of the PHRC is available from http://phrc.lshtm.ac.uk/.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for the review; it drew on previously published studies.