For a French translation of this position statement, please see the Supplementary Material at DOI: 10.107/cem.2018.26

The CAEP Acute Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Best Practices Checklist was created to assist emergency physicians in Canada and elsewhere manage patients who present to the emergency department (ED) with acute/recent-onset atrial fibrillation or flutter. The checklist focuses on symptomatic patients with acute atrial fibrillation (AAF) or flutter (AAFL), i.e. those with recent-onset episodes (either first detected, recurrent paroxysmal or recurrent persistent episodes) where the onset is generally less than 48 hours but may be as much as seven days. These are the most common acute arrhythmia cases requiring care in the ED.Reference Connors and Dorian 1 , Reference Michael, Stiell, Agarwal and Mandavia 2 Canadian emergency physicians are known for publishing widely on this topic and for managing these patients quickly and efficiently in the ED.Reference Scheuermeyer, Innes and Pourvali 3 - Reference Stiell, Clement and Rowe 5

This project was funded by a research grant from the Canadian Arrhythmia Network and the resultant guidelines have been formally recommended by the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP). We chose to adapt, for use by emergency physicians, existing high-quality clinical practice guidelines (CPG) previously developed by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS).Reference Stiell and Macle 6 - Reference Macle, Cairns and Leblanc 8 These CPGs were developed and revised using a rigorous process that is based on the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system of evaluation.Reference Gillis and Skanes 9 , Reference Guyatt, Oxman and Vist 10 With the assistance of our PhD methodologist (IG), we used the recently developed Canadian CAN-IMPLEMENT© process adapted from the ADAPTE Collaboration. 11 - Reference Harrison, van den Hoek and Graham 13 We created an Advisory Committee consisting of ten academic emergency physicians (one also expert in thrombosis medicine), four community emergency physicians, three cardiologists, one PhD methodologist, and two patients. Our focus was four key elements of ED care: assessment and risk stratification, rhythm and rate control, short-term and long-term stroke prevention, and disposition and follow-up. The Advisory Committee communicated by a two-day face-to-face meeting in March 2017, teleconferences, and email. The checklist was prepared and revised through a process of feedback and discussions on all issues by all panel members. These revisions went through ten iterations until consensus was achieved. We then circulated the draft checklist for comment to approximately 300 emergency medicine and cardiology colleagues; their email written feedback was further incorporated and the final version created and approved by the panel.

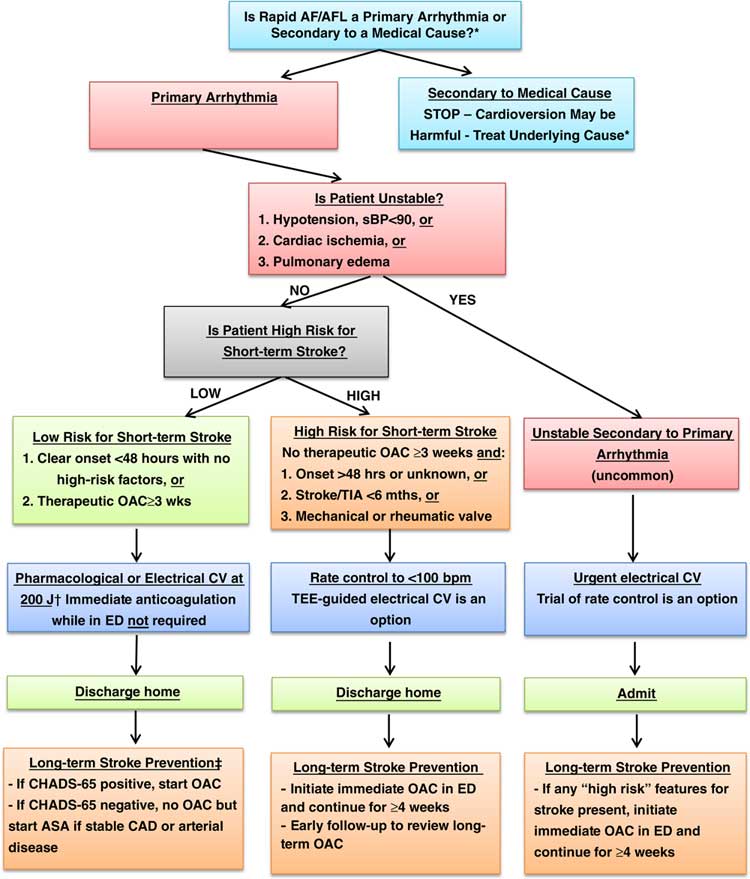

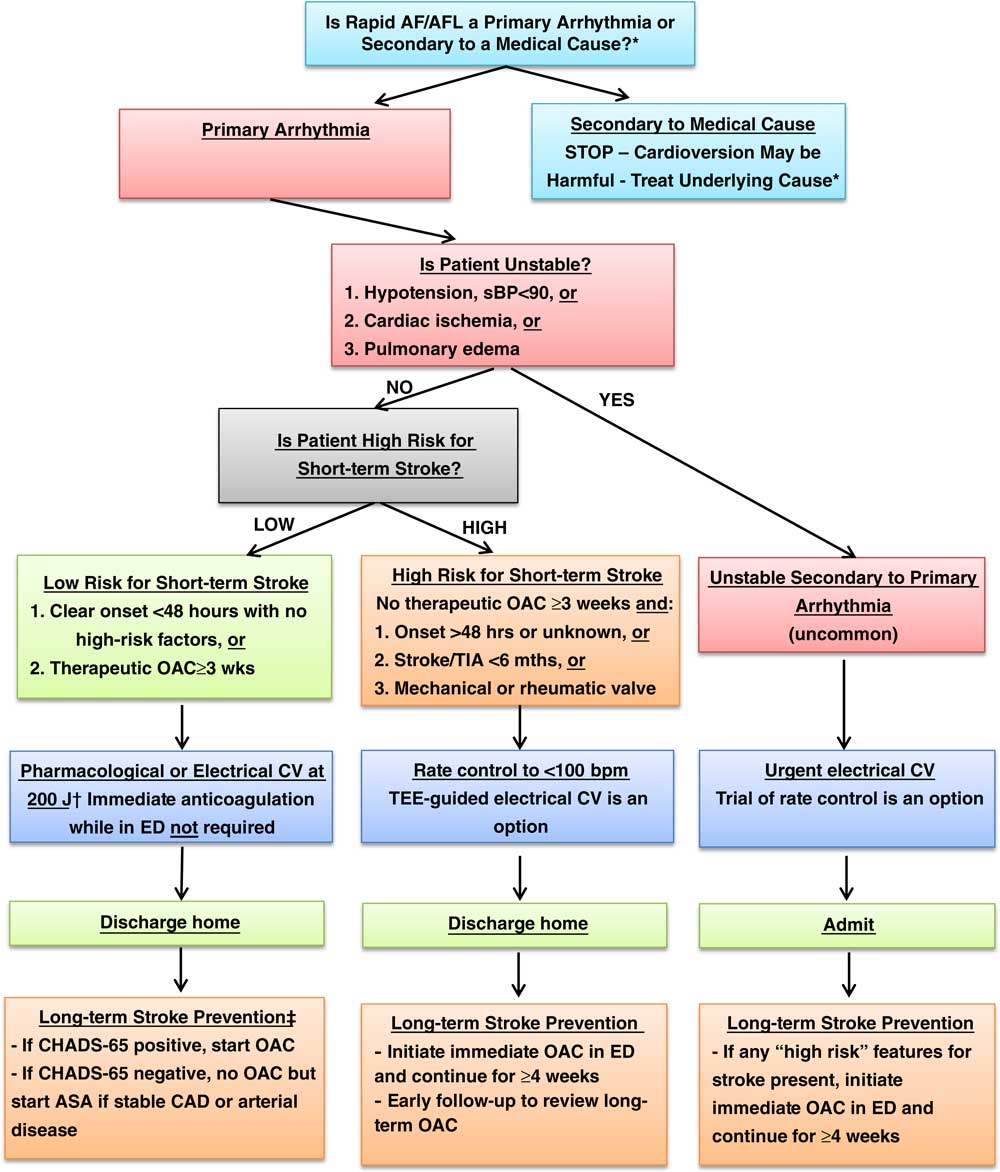

During the consensus and feedback processes, we addressed a number of issues and concerns, some of which required extensive discussion. We spent considerable time defining what is meant by “unstable” and highlighting the issue that many unstable patients are actually suffering from underlying medical problems rather than a primary arrhythmia. Where possible we chose to simplify the checklist, for example listing only procainamide for pharmacological cardioversion. Other drugs were considered including vernakalant, ibutilide, propafenone, flecainide, and amiodarone. We also tried to give specific drug dosage recommendations, recognizing that physicians are free to consult any number of excellent pharmaceutical references. The panel believes that, overall, a strategy of ED cardioversion and discharge home from the ED is preferable from both the patient and the healthcare system perspective, for most patients. One controversial recommendation is to consider rate control or transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)-guided CV if the duration of symptoms is 24-48 hours and the patient has two or more CHADS-65 criteria. This is based on some recent data from Finland.Reference Nuotio, Hartikainen and Gronberg 14 , Reference Stiell, Healey and Cairns 15 We emphasize the importance of evaluating long-term stroke risk by use of the CHADS-65 algorithm and encourage ED physicians to prescribe anticoagulants where indicated.

Our hope is that the CAEP Acute Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter Best Practices Checklist will standardize and improve care of AAF and AAFL in large and small EDs alike. We believe that these patients can be managed rapidly and safely, with early ED discharge and return to normal activities.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this guideline was supported by the Cardiac Arrhythmia Network of Canada (CANet) as part of the Networks of Centres of Excellence (NCE). IS has received funding from Boehringer Ingelheim Canada Ltd. and from JDP Therapeutics for participation in clinical studies. PA has received research funding and/or honoraria from BMS-Pfizer Alliance, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Servier, KD has received research funding from Bayer. MD has received honoraria and research funding from Biosense Webster, Bayer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Abbott, and Servier. AS has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Pfizer, and Servier. TT has received honoraria from Cardiome Pharma Corp. We thank the hundreds of Canadian emergency physicians and cardiologists who reviewed the draft guidelines and who provided very helpful feedback.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2018.26

APPENDICES

Figure 1 Overall management algorithm for patients presenting to the ED with acute atrial fibrillation or flutter. Adapted from CCS 2014 Figure 2.7 Notes. * Consider medical cause (e.g. sepsis, bleeding, PE, heart failure, ACS, etc) if not sudden onset, HR<150, fever, known permanent AF; cardioversion may be harmful, rate control discouraged; investigate and treat underlying condition aggressively † Consider rate control or transesophageal echocardiography (TEE)-guided CV if duration 24-48 hrs and two or more CHADS-65 criteria ‡ If CHADS-65 positive, start OAC; if stable CAD, discontinue ASA; if CAD with other anti-platelets or recent PCI, consult cardiology (see Figure 2) ASA=acetylsalicylic acid; CAD=coronary artery disease; CHADS-65=age 65, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes, stroke / transient ischemic attack; CV=cardioversion; NOAC=novel direct oral anticoagulant; OAC=oral anticoagulant; TIA=transient ischemic attack.

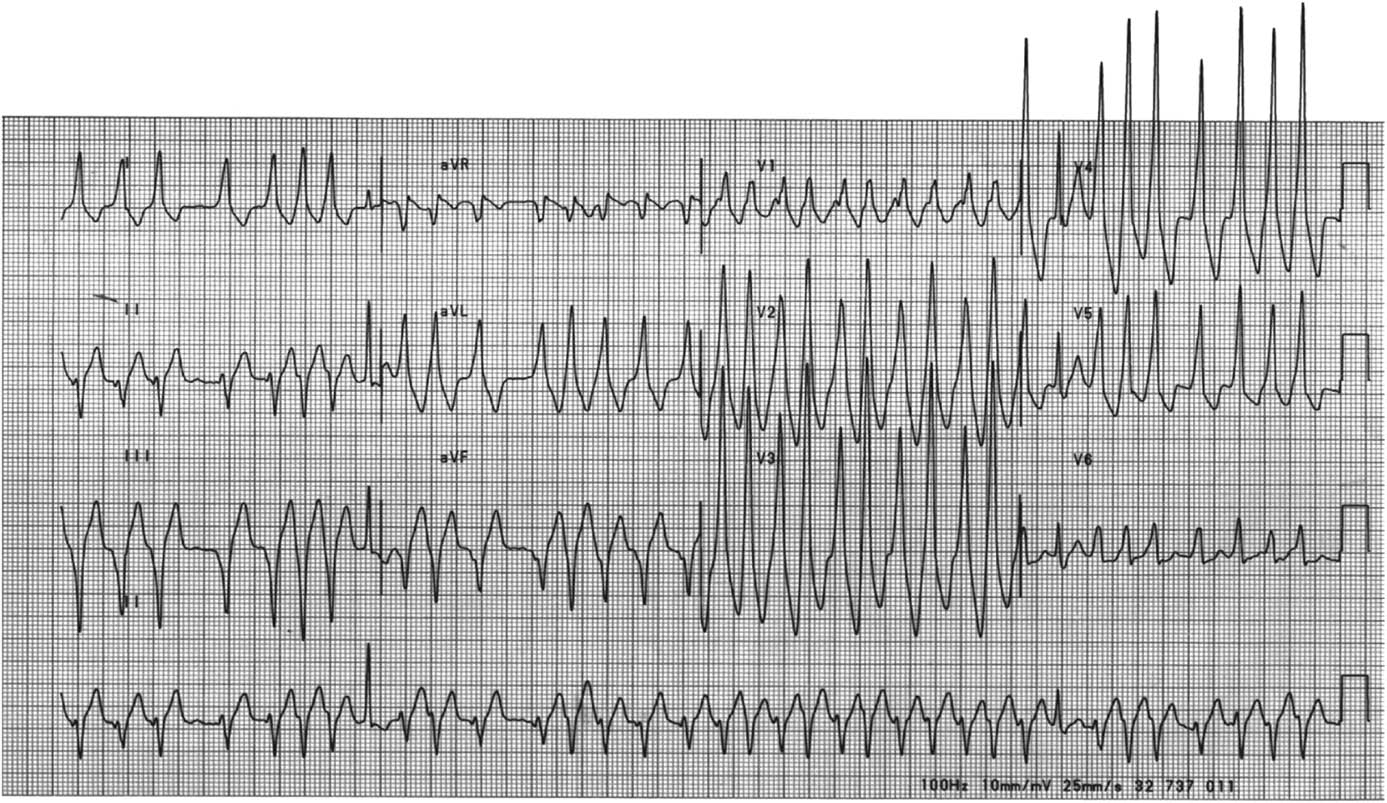

Figure 2 Rapid Ventricular Pre-Excitation

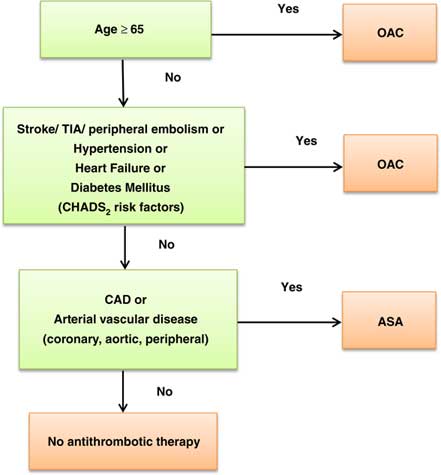

Figure 3 “CCS algorithm” (“CHADS65”) for long-term stroke prevention in AF